|

|

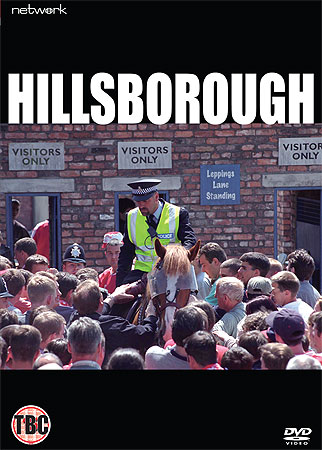

Hillsborough (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th September 2009). |

|

The Show

Hillsborough (Granada, 1996)

The critical consensus suggests that the late-1980s saw the demise of traditional ‘authored’ television drama, due to the increased commercialisation of British television throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. Thanks to the growth of multichannel television during the late-1980s and 1990s, during this era British broadcasters were increasingly driven by a need to compete with one another through winning new audiences. The need to win and retain new audiences led both the BBC and ITV, who were still the major broadcasters within the UK, to increasingly rely on the commissioning process (which removed creative power from writers and placed it into the hands of producers) and to emphasise the production of ‘established star vehicles’ – star-led series like Inspector Morse (Central, 1987-2000) and A Touch of Frost (Yorkshire, 1992- ) (Duguid, 2009: 7). Consequently, television drama became increasingly conservative. Whereas until the 1980s British television had largely been ‘writer-focused’ and had ‘privileg[ed] the writer’ as a means to foster ‘quality drama’, the increasingly commercial television climate of the late-1980s and 1990s led to an antipathy within the British television industry towards traditional ‘authored’ drama (Brandt, 1993: 120). As Lez Cooke states in British Television Drama: A History, ‘the writer with “authorial vision” was now considered to be a luxury that most television companies could no longer afford’ (164). Meanwhile, the traditional training grounds for new writers of authored drama – including expensive-to-produce single-play strands such as the BBC’s Play For Today (1970-84) and ITV’s Armchair Theatre (ABC, 1956-74) – had gradually died off (see Caughie, 2000: 203-4; Duguid, op cit.: 9). Drama series were increasingly based on ideas from commissioning editors, and in the increasingly competitive climate created by multichannel television they had to be seen to be ‘marketable projects which could win and retain audiences’, hence the reliance on vehicles for established stars such as David Jason and John Thaw (Cooke, op cit.: 164; see also Cooke, 2008: 170-1). An exception to the decline of authored drama is the work of Jimmy McGovern. McGovern began his career as a television writer with work on Channel 4’s soap opera Brookside (1982-2003). McGovern’s work is ‘authored’ in the sense that it displays certain preoccupations: these are principally a focus on the struggles of the Northern working-class, the decline of socialism and the attacks on the trade unions during the 1980s, and issues relating to Liverpool-born McGovern’s own Catholic upbringing. In his work on Brookside, McGovern frequently voiced these concerns through the character of Bobby Grant (Ricky Tomlinson): ‘a socialist, an active trade unionist, a Catholic, a father of three: his [Grant’s] biography was strikingly similar to McGovern’s own’ (Duguid, op cit.: 12). However, McGovern became disillusioned with the left following the Hillsborough disaster on the 15th of April in 1989, when ninety-six Liverpool supporters died at the FA Cup semi-final, which took place at the Hillsborough stadium in Sheffield. The deaths were caused by overcrowding, which was a result of ‘a combination of inadequate safety procedures and defective crowd management’ by the South Yorkshire police (ibid.: 13). When a senior police officer, Chief Superintendent Duckenfield, decided to open a locked gate and drive fans into the stadium’s already-packed two central pens, the overcrowding turned into a stampede. Fans who, in an attempt to escape the crowding, tried to climb the fence onto the pitch were driven back by the police, who interpreted the fans’ actions as a pitch invasion. After the disaster, Duckenfield claimed that the locked gate had been forced open by the Liverpool fans and encouraged his officers to manufacture evidence as a way of avoiding culpability; twenty years on, the families of the victims are still engaged in a battle to encourage the South Yorkshire police to admit their responsibility for the event and acknowledge that the police ‘amended’ their reports in order to cover-up their role in the disaster (see Conn, 2009: np). Duckenfield’s lies led to a number of myths that were circulated in the gutter press, most notably in The Sun, which under the headline ‘The Truth’ claimed that some of the Liverpool fans ‘picked pockets of victims’ and ‘urinated on the brave cops’, whilst other ‘drunken Liverpool fans viciously attacked rescue workers as they tried to revive victims’. The publication of these unsupported allegations made The Sun, and especially its then-editor Kelvin MacKenzie, an object of hate in Liverpool.

By 1996, McGovern had already tried to deal with the fallout from the Hillsborough disaster through ‘To Be a Somebody’, one of the most highly-regarded storylines from the McGovern-created police drama series Cracker (Granada, 1993-2006). For McGovern, the fallout from the Hillsborough disaster offered a ‘symbolic representation of the progressive abandonment of the white working class [….] [T]he popular image of the working class is inextricably tied up with football, the sole surviving mass working-class pursuit in an era that has seen all other vestiges of working-class pride, from the traditional industries of coalmining, textiles and engineering to the historic links between organised labour and the political party that bore its name, swept away’ (Duguid, op cit.: 67, 70). When football supporters began to be treated with contempt by both the police and the press, ‘the tragedy of Hillsborough was, for […] McGovern, inevitable. Hillsborough marks the culmination of the attack on white working-class culture that began on the right and was joined from the left’ (ibid.). In ‘To Be a Somebody’, the storyline that began the second series of Cracker, police psychologist Eddie ‘Fitz’ Fitzgerald (Robbie Coltrane) is drawn into a case involving Albie Kinsella (Robert Carlyle), a Hillsborough survivor who, in vengeance for the disaster, kills ‘both a policeman and a Sun reporter’ (ibid.: 68). Acting as a mouthpiece for McGovern, Albie justifies his crimes through a ‘bitter analysis of the demonisation and betrayal of the white working class’ represented by both the irresponsibility of the South Yorkshire police’s actions at Hillsborough and The Sun’s callous coverage of the event.

In his BFI-published monograph on Cracker, Mark Duguid notes that the tragedy of Hillsborough ‘is at the root of McGovern’s distinctive fusion of grief and anger [….] It is Hillsborough that taught McGovern that grief may as easily tear a family apart as bring it together’ (ibid.: 86). In McGovern’s Hillsborough, the focus is on the devastation that the event caused to a small group of families. At the centre of the narrative are Trevor and Jenni Hicks (Annabelle Apsion), who are forced to deal with the deaths of their daughters Victoria (Anna Martland) and Sarah (Sarah Graham). (Trevor Hicks is played by long-time McGovern collaborator Christopher Eccleston, who had featured as Detective Inspector Billborough in Cracker and had taken the lead role in McGovern’s school-set drama Hearts and Minds (BBC, 1995).) In the wake of the Hillsborough disaster, Jenni and Trevor’s relationship falls apart as they both deal with their grief in different ways: ‘The two people in this, you couldn’t have loved them […] You’ve gone back to work, as if nothing ever happened. Busy, busy, busy’, Jenni tells Trevor accusingly. Eventually, Trevor and Jenni’s marriage breaks down, and a very late scene in the drama shows them splitting up their personal effects and the belongings of their two deceased daughters. The effects of grief are also shown through the experiences of John Glover (Ricky Tomlinson, another long-time collaborator with McGovern) and the loss of his son Ian (Stephen Walters).

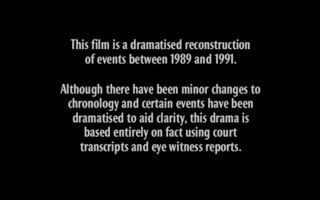

Hillsborough is a drama-documentary, a genre that is often accused of being neither fish nor fowl. However, McGovern went to great lengths to ensure the accuracy of the events depicted in his dramatisation of the event; in this, he was aided by former-World in Action producer Katy Jones, who was hired as Hillsborough’s factual producer (see McGovern, 2004: np). The drama opens with a title card* which acknowledges that it is a dramatisation of the events rather than a documentary, but McGovern’s meticulous research is evident throughout. The narrative is told in a linear manner, beginning with the families and the police preparing for the match, continuing through the disaster itself and its immediate aftermath, and spending the bulk of its running time following the actions of the Hillsborough Families Support Group, chaired by Trevor Hicks, and the Hillsborough Justice Campaign as they battle to make the South Yorkshire police accountable for the disaster. The central narrative is intermittently interrupted through to-camera monologues by actors depicting the survivors, families of the victims and the police. Real-life footage of the incident is used to illustrate the disaster itself. In the opening monologue, one of the victims’ family members states that ‘The Chief Constable of South Yorkshire said that we shouldn’t do the programme: it’ll upset the families of the dead. I’m one of those families: my son died at Hillsborough, and I want the truth’.

Understandably, at the heart of the drama is a distrust of the ‘higher ups’ in the South Yorkshire police. This is even shared by the regular PCs: the police are introduced listening to a lecture by Duckenfield on how to manage the fans at the game. ‘Who is this wanker?’, one of the PCs asks. ‘Duckenfield’, he is told. ‘When did he arrive?’, the PC asks. ‘Three weeks ago’, he is informed. ‘Three weeks ago?’, the PC queries in amazement. Later, after the gates to the central pens have been opened, Trevor Hicks is shown pleading with Duckenfield not to drive the fans into the central pen. ‘Will you do something? My daughter’s in that pen?’, Hicks begs. He is told coldly, ‘Shut your fucking trap up’. After the event, the police are shown being warned by a senior colleague, ‘Don’t put anything in your notebooks’. However, one of the more savvy PCs quietly tells his colleagues, ‘Put everything in your notebooks’.

Immediately after the disaster, the police are seen fishing for explanations that would let them off the hook by refocusing the blame on the surviving Liverpool fans, asking the survivors how much they alcohol they had been drinking before and during the match. Just after viewing his daughter Sarah’s body, Trevor is asked by a policeman, ‘How much did you have to drink?’ ‘I don’t see how that is relevant’, he replies. Shortly after, Trevor reflects on the way that he and the other fans were treated by the police: ‘They [the police] treated us like scum’, Trevor tells his wife Jenni: ‘It’s guilt. Scores of people dead, thanks to them. Unbearable. They don’t think of them as people: they think of them as scum’. Hillsborough is an exceptional television drama, written by one of British television's major writers. Extraordinarily powerful, it is supported by McGovern’s careful research; the drama has a very human focus, with its emphasis being on the families and the ways in which they are torn apart by grief. As Hicks tells the press at one point, ‘Football was the one thing we did as a family, and now we’re not a family anymore’. Hillsborough seems to be uncut and runs for 99:53 mins (PAL).

* The opening title card reads: ‘This film is a dramatised reconstruction of events between 1989 and 1991. Although there have been minor changes to chronology and certain events have been dramatised to aid clarity, this drama is based entirely on fact using court transcripts and eye witness reports’.

Video

Hillsborough is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 1.78:1, with anamorphic enhancement. Colours are natural and the image is clear and detailed. Shot on digital video and clearly an expensive production, Hillsborough looks absolutely gorgeous, especially during the night scenes.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. This is without problems. Dialogue is always audible; the dynamic range of this audio track is evidenced throughout the scenes that depict the Hillsborough disaster itself, which thanks to some wonderful sound design are extremely potent. However, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Sadly, there is no contextual material. It would have been helpful to put the drama into some form of context, either by way of an interview with McGovern or through some reflection on the Hillsborough disaster itself.

Overall

Hillsborough is a real gem, written by one of the few working writers of ‘authored’ television drama. Hillsborough is extremely powerful, and at times (especially during the scenes depicting the Hillsborough disaster itself) it can be difficult to watch. However, this is a truly enlightening drama, and is characteristic of McGovern’s anti-establishment stance: McGovern is truly critical of the corrupt institutions that, for so long, covered-up the South Yorkshire police’s mismanagement of the event. This release is timed to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of the event, and it is the first release of this excellent drama on any home video format. This release comes with the strongest possible recommendation. Sources: George W. Brandt, 1993: British Television Drama in the 1980s. Cambridge University Press John Caughie, 2000: Television Drama: Realism, Modernism, and British Culture. Oxford University Press David Conn, 2009: ‘Hillsborough: how stories of disaster police were altered’. The Guardian (13 April, 2009). [Online.] http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/2009/apr/13/hillsborough-disaster-police-south-yorkshire-liverpool Accessed September 2009 Lez Cooke, 2003: British Television Drama: A History. London: British Film Institute Lez Cooke, 2008: The Television Series: Troy Kennedy Martin. Manchester University Press Mark Duguid, 2009: BFI TV Classics: ‘Cracker’. London: British Film Institute Jimmy McGovern, 2004: ‘The power of truth’. The Guardian (10 June, 2004). [Online.] http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2004/jun/10/features.features11 Accessed September 2009 For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|