|

|

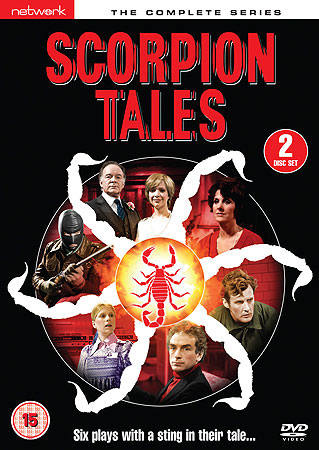

Scorpion Tales: The Complete Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (30th November 2010). |

|

The Film

Scorpion Tales (ATV, 1978)

A largely-forgotten anthology series broadcast on ITV, Scorpion Tales (ATV, 1978) predated the production of ITV’s most popular anthology series, Tales of the Unexpected (Anglia Television, 1979-88), by a year. Like Tales of the Unexpected, each story in Scorpion Tales has a sting in its tail; hence the title of the series. However, some of the stories have more ‘bite’ than others.

‘Easterman’, the first episode, is written by Ian Kennedy Martin and is easily one of the highlights of the series, largely thanks to Kennedy Martin’s writing and Trevor Howard’s portrayal of the embittered Detective Chief Inspector George Mavor. The episode opens by outlining Mavor’s antagonistic relationship with his colleagues: ‘You’re animals’, he declares to a group of silent, uniformed policemen who have arrested him for drink driving. ‘You’re the crap that gives the public a target’, he continues before describing one of the policemen as ‘a gutter punk, son, and a liar’. Mavor, who has nine months to retirement, tries to get the charge ‘buried’ by asserting that he was responding to a call. Mavor is given the task of investigating an attack on a policeman, who was knocked unconscious by a blow to the head; a note left on the officer’s lapel was addressed to Mavor and signed ‘Easterman’. Assisted by a junior detective, Purcell (Paul Arlington), Mavor seeks to identify who ‘Easterman’ is. Eventually, Mavor is ambushed by Easterman (Don Henderson) in a derelict building, where Easterman humiliates Mavor by putting the barrel of a rifle into Mavor’s mouth (‘I’ve been waiting for this for so long, like I was born to hunt you’, Easterman declares). Easterman seems to hold a personal grudge against Mavor, and the climax (which has echoes of the closing sequence of Mike Hodges’ 1971 film Get Carter) suggests that Easterman’s revenge is metaphoric payback for Mavor’s outspoken prejudices against homosexuality and Christianity.

The episode offers an excellent character study that focuses on the bitter, isolated Mavor. Mavor offers a challenge to the conformity engendered by the police force, and in fact addresses the uniformed officers with thinly-veiled contempt, in the opening sequence referring to the uniformed policemen as ‘Hitler Youth’ and later in the episode labelling uniformed officers as ‘Nazis’. In one sequence, Mavor tells Purcell, ‘Last night the super [superintendent] gave me the Richard Dimbleby lecture on retirement. [He] painted me as a walking shambles, falling apart at the seams [….] You think diplomacy works, don’t you? You think: “In nine months, I’ll be rid of him. I play my cards right; I’ve got a pretty wife; I smile well” [….] Well, you’re wrong, Purcell: you need more than a smile. You need sharp serrations, edge, the ability to raise your voice just loud enough so that no-one will question your orders. Son, the top people are not made out of grinning accountants; they’re made out of people like me, who shove our way up’. There is more than a suggestion that Mavor’s experiences have a policemen have soured his relationships and his worldview, stretching him to breaking point – much like Detective Sergeant Johnson (Sean Connery) in Sidney Lumet’s 1973 film The Offence (adapted from the play This Story of Yours by Z Cars writer John Hopkins), whose poster declared ‘After 20 years, what Detective Sergeant Johnson has seen and done is destroying him’. Like Johnson in Lumet’s film, Mavor is an apparently idealistic man who has developed a bitter shell. The play channels The Offence in its depiction of the effects that witnessing the depths of human behaviour have on a career policeman. When asked what he believes in by a Christian copper, George replies: ‘High prices, lost ambition, my own private prison of loneliness […] I believe that life’s a game written in braile, for those of us who are actually deaf, not blind. I believe we’re led on by the whore of promise, castrated by the sheer awesomeness of it all [….] In the end, I believe we die of pity. Pity for everyone; pity for ourselves, for falling for the oldest con trick’. Mavor’s idealistic core is foregrounded when, after chewing out a subordinate for making a mistake that results in the loss of vital forensic evidence, George says, ‘There are two words that have followed me through every second of a life put in this job: “I care”. I care so passionately about this work that I would never have made the mistake that you just made. You’re a bastard catastrophe, son [….] Do you ever have any time in your life that you think, sonny? While you’re on the crapper, for instance? Next time you’re sitting there, think about this: that a man who spent thirty years as a copper, an expert, told you on the basis of one act of yours […] to get out of this work, out of care for this institution, because this bloody institution will only survive whilst people do care [….] Go and get yourself a job in some shop selling jeans or gramophone records, but for Christ’s sake get out of here’. Later, Mavor visits a doctor and tries to acquire a prescription for ‘valium and librium, the tranquilisers on which we all survive’. Mavor discusses the differences between his work and the work of the doctor: ‘There are similarities between our two impossible careers, but at least the people you deal with respect you: they don’t spit on you. Small things after 30 years take a toll [….] It’s coming to an end, but I don’t even care anymore’.

Mavor’s behaviour becomes increasingly self-destructive (‘It’s a spectacular temptation, isn’t it? To go out there and make bloody sure he finds me’, he asserts in one sequence). In one scene, the superintendent tells Mavor, ‘I’m worried about you [….] It falls apart, the last year. Motive, discipline. There’s a looking back: “What has the job done for me?” Answer: maybe a waste of life. There’s a looking forward: […] pension, spiralling cost of living’. Mavor responds by asserting, ‘You sound like Margaret Thatcher’. To this, the superintendent replies, ‘I’ve seen all this before: men who have given their lives to the force, in the last year becoming a refuse bank for stupid behaviour and self-pity’. However, Mavor unconvincingly declares that ‘I’ve got sting in my tail. Now don’t you worry, and don’t you forget it [….] I’m going [out] the way I’ve always been: hostile’. Filled with sharply-written, quotable dialogue that is delivered with utter conviction by Trevor Howard, ‘Easterman’ is an effective and memorable drama that suffers slightly from a rushed resolution. Kennedy Martin’s experience writing for police dramas, including The Sweeney (Thames/Euston Films, 1974-8), is evident throughout, and ‘Easterman’ is arguably the strongest episode in this series.

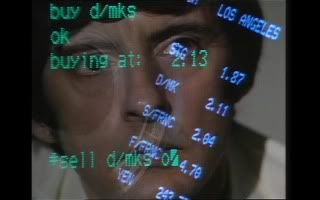

‘Killing’, written by Doctor Who scribes Bob Baker and Dave Martin, features Jack Shepherd as Mark Hawkins, a computer programmer who works at night in an almost-deserted office building. Hawkins has developed a scam whereby he uses company money and a specially-designed computer programme to buy and sell currency on the stock market. However, one night he is introduced to a new colleague, Mrs Martha Fredricks (Angela Down), who has been hired to work with Hawkins at night. Fredricks is wary of Hawkins, who during their first meeting is drunk; she sees Hawkins as workshy, and returning home she tells her husband Ross (Michael O’Hagan), who works as a statistician within the Criminal Records Office, that ‘All he [Hawkins] does is drink’. Fredricks considers reporting Hawkins, and complains that he doesn’t help and that the job they are doing for the company ‘will take months [….] I want to get the job done’. However, Hawkins complains to Fredricks about the company’s treatment of its bank of computers: ‘They’ve got a good system here, and they’re going to scrap it. They’re frightened, you see’, he tells her. Hawkins explains that it is in both his and Fredricks’ interest to stretch the job out for as long as possible.

One night, Hawkins questions the distribution of wealth, suggesting that ‘Computers could run the world’. ‘Are you a Marxist?’, Fredricks asks warily, later telling her husband Ross that ‘I think he’s [Hawkins is] mad’. However, Martha and Ross suffer from the same kind of money-related problems that Hawkins suggests are endemic within society: at one point, Ross tells his wife that ‘My life’s screwed up, Martha; all because of bloody money’. One night, Martha notices a problem in the computer’s software and realises that there may be another programme tape (ie, the tape containing Hawkins’ programme) in existence. She begins to investigate and uncovers evidence of Mark’s scheme before making a attempt to extort Hawkins for two thirds of the money he obtained – enough to assuage the Fredricks’ financial worries. Meanwhile, Martha’s husband begins to suspect that Martha and Hawkins are conducting an affair.

‘Killing’ is interesting for its depiction of people’s attitudes towards technology at the end of the 1970s. When Martha notices a problem in the computer’s software, Hawkins tells her, ‘You’re too conscientious, Martha. Nobody’s going to thank you for this [….] It’s a machine, Martha. It’s nothing but a glorified adding machine. It doesn’t really think: it just does what it’s told’. ‘But it doesn’t’, Martha protests. The episode is held together by Shepherd’s performance as the internal, conflicted Hawkins, a man who although respected by his colleagues has an antagonistic relationship with authority, capitalism and life in general (‘If you don’t eat life, life will eat you’, he tells himself at one point).

‘The Great Albert’ is another strong episode. It opens with a young boy, Matthew Ward (Max Harris), questioning God why the things he asked for haven’t been done, before asserting that he will go elsewhere for help: ‘Everything is wrong. I can’t see why you can’t let one thing put one thing right. Anyway, I’ll find some other way to help. I’m sorry it couldn’t be you’. Soon, the audience is privy to why Matthew sought help through prayer. His mother, Virginia Ward (Lynn Farleigh), is a cruel woman, seemingly an alcoholic, who speaks unnecessarily harshly to Matthew when he interrupts a party she is holding. She also seems to be having an affair and is utterly selfish: when Matthew’s parents argue about getting a divorce and Matthew’s father warns Virginia that she will wake Matthew, she screams hysterically, ‘I don’t give a shit if I wake the little sod up or not; I’m talking about me and my life’. Meanwhile, Matthew’s father, Peter Ward (Kenneth Gilbert), is kind but distant, and seems unable to defend Matthew from Virginia’s psychological cruelty. As a result, Matthew spends more time with the family’s housekeeper, Mrs Withers (Gwen Nelson), than with his parents. However, Mrs Withers comes into conflict with Virginia after asserting that she refuses to lie to Matthew about Virginia’s affair; Virginia retaliates by firing Mrs Withers, leaving Matthew without an ally.

One evening, Peter sees his father, who is apparently an antique dealer of some kind, handling a book which he plans to sell; the book is a grimoire, and after hearing his father talk about the book, Matthew decides that the pages from the grimoire (and the spells they contain) may provide a way of solving his problems. Stealing copies of the pages, Matthew shares them with one of his friends. Matthew starts small, by reciting a simple spell to make it rain. The spell seems to work. After this, Matthew becomes increasingly absorbed in the grimoire, and when his father makes preparations to leave, Matthew takes down the picture of Christ that is in his bedroom and consults the ancient book, conducting a spell that is intended to make his father stay. When the spell doesn’t seem to work, Matthew walks back to the house, begging ‘Oh, please help me, Lucifer. I’ve done everything right’. At the house, through one of the windows Matthew sees his father being murdered by his mother’s lover. Alone and convinced that his mother’s lover is Lucifer in a corporeal form (‘How do I make you go away? I’ve lost the book’, Matthew asks his mother’s lover), Matthew struggles to find restitution for his father’s murder.

‘The Great Albert’ is interesting for the moral dilemma that Matthew faces. In one sequence, as Matthew’s father prepares to leave the family home, Matthew asks Peter, ‘If you want something really badly, and it can only bring happiness, does it matter the way you go about getting it? Does it? [….] If the end is happy and good, does it matter the way you get there, what you do?’ Peter replies simply that, ‘I suppose not, as long as you don’t break the law or hurt anyone’. The episode also has an interesting ambiguity surrounding the supernatural: the results of Matthew’s spells could be nothing more than mere coincidence, although Matthew believes that the grimoire truly has magical powers and, due to his desperately unhappy home life, substitutes his Christian faith for black magic. The episode never confirms the existence of supernatural forces, and the viewer is left with the suggestion that the intimations of the supernatural may all be in Matthew’s head; however, the psychological effects for the young boy are just as potent as if the supernatural was ‘real’.

‘The Ghost in the Pale Blue Dress’ opens with a board meeting of the heads of a merchant bank. At the meeting, Toby Grafton (Brian Stirner), the son of the bank’s chairman Sir Wilfred Grafton (Tony Britton), is chastised for his new ideas: he wants the bank to take more risks, investing in up-and-coming companies (‘It’s about time we moved into the Twentieth Century [….] We’ve become so bloody conservative [that] we’re covered with cobwebs’, he tells the other men). The conflict between Toby and his father is delineated in the opening sequences. Toby’s girlfriend Karen (Sandra Payne) visits Sir Wilfred in the attempt to force some kind of reconciliation between father and son. ‘Do you love him?’, Toby’s father asks her. ‘Very much’, she replies. ‘Then you have my sympathy’, Sir Wilfred responds. He invites Karen and Toby to a dinner party but specifies that she must wear a pale blue dress ‘Because I think it would suit you’.

However, when Toby sees Karen in her dress before the dinner party, he chastises her: ‘You’re not wearing that dress. You can’t’, he asserts angrily. Later, we discover that Toby’s concern about Karen’s dress stems from her striking resemblance to Sir Wilfred’s former wife. At the party, Toby’s father tells Karen that he knows she and Toby met through ‘a computer dating service’: Karen had been in a convent and, when she left the convent to work in a gallery, was struggling to find suitable men with whom she could socialise, and as a consequence she turned to the computer dating service through which she eventually met Toby. However, Sir Wilfred suspects that his son is gay: ‘You may think there is no such thing as a fate worse than death, but there is: marriage to a homosexual’, Toby’s father tells Karen in front of the other guests at the party. Karen then begins to suspect that Toby has chosen her, due to her resemblance to Sir Wilfred’s dead wife, as a way of spiting his father. She also begins to suspect that Sir Wilfred’s assertion of Toby’s homosexuality is true: she and Toby have not slept together, despite Karen’s desire to do so. When confronted by Karen’s suspicions, Toby declares ‘I told you: I’m old-fashioned about that sort of thing [….] Father’s a cunning bastard: he knew the poison would spread’. Toby and Sir Wilfred become involved in a conflict that threatens to destabilise the hierarchy within the bank, and the relationship between the two men and Karen becomes increasingly ambiguous.

‘The Ghost in the Pale Blue Dress’ develops from an interesting premise but arguably overstays its welcome. Whereas all of the episodes are to some degree studio-bound, ‘The Ghost in the Pale Blue Dress’ is curiously static; despite some strong performances, it’s arguably the weakest episode in this series.

‘Crimes of Persuasion’ begins with a television interview: Sir Robert Haines (Anthony Bate) is being questioned by television presenter Jeremy Hope (Brett Usher). The interview is less than amicable, and Haines strongly states his opinions on capital punishment: ‘It is surely obvious to everyone, except perhaps to a small minority of opinion makers, journalists, etcetera, that something has to be done’, Haines asserts; ‘Our society is becoming increasingly violent. Politically-motivated murder is almost commonplace, and every year sees an increase in acts of terrorism designed to destroy our system of government and which involve murder of innocent women and children’. Haines then asserts that he would ‘reintroduce the death penalty for politically-motivated murder’. When asked about whether he would reintroduced the death penalty for crimes of passion, Haines declares that ‘It’s a European idea, a fallacy, that has somehow contaminated us, that uncontrollable emotion is somehow a mitigating factor. We are all responsible for our emotions, even the psychopath, the insane’. He claims that ‘on behalf of society’ he would be willing to ‘send a man to the gallows’. However, Hope makes Haines uncomfortable when asking him, ‘Is it not true […] that you do business with governments abroad who are guilty of murders even more atrocious than those of the IRA?’ The television interview is intercut with shots of a woman returning to her flat. The woman is Jean Newman (Susan Engel), Haines’ mistress for ten years. Newman is unhappy in her relationship with Haines, which has begun to stagnate, and is in the process of renting out her flat. Not long after Newman returns home, she is visited by Samantha Robinson (Chloe Salaman), a young woman who wishes to view the flat.

Meanwhile, Haines is approached after the television interview, and the episode crosscuts between the events in the flat and Haines’ meeting with the deposed prime minister of a Middle Eastern country. Haines seems to be plotting a ‘return to power’ for the Middle Eastern prime minister, telling him that ‘I enjoyed our association. When you were prime minister, we traded together with such excellent results’. In response to this, the Middle Eastern man – who speaks in pidgin English – makes his own extreme views known, declaring ‘Is it wrong to put in prison a bomb thrower who does many damages? The Marxists make always trouble. Now we have bad government. My country is in bad times, Robert [….] When times change, we do business again. I put all Marxists in prison; I chop off lots of heads, yes. Until then, I live in Bayswater. I look at the green grass; I watch the people buying at the boutiques’. In Jean’s flat, the telephone rings; Jean answers it, only to find an anonymous caller on the other end of the line. Shortly afterwards, a bomb goes off outside the flat; Jean seems remarkably unfazed but Robinson is visibly shaken. Later, after Robinson has left and Haines has arrived at Jean’s flat, Haines shows the prejudices he has hidden through his television interview and meeting. Reflecting on his meeting with the Middle Eastern man, Haines declares, ‘WOGS, Workers on Government Service, W-O-G-S. That’s where it comes from. You know, Egypt. I had my fill of them tonight. Deceitful, undeniable wogs. It must have been nice in the old days, where the louder you shouted the more obsequious they became’. He then turns his attention to Jean’s gender, declaring ‘No nonsense about you, though […] No Women’s Lib rubbish: You know how to make a man happy. I suppose that’s pretty rare these days’. Jean begins to show a subtle dislike of Haines. Haines presents her with an item of jewellery to celebrate the ten years of their affair. However, the events are interrupted by two more anonymous telephone calls, each of which leave Jean visibly distraught, and Jean’s attitude towards Haines develops into one of outright hostility. ‘Do you ever get ruffled, Robert?’, Jean asks Haines. She confronts his use of language: ‘I’m sorry to use such vulgar expressions, but when you’ve been somebody’s Friday night lay for the last ten years, the refined areas of the mind do tend to wither’. When Haines is visibly upset by Jean’s use of the word ‘lay’, Jean responds by asserting that ‘There are people, quite intelligent people, who would consider it far less offensive to use the word “lay” than to call an Arab a “wog”’. Jean reflects on her relationship with Haines, the characteristics that first drew her to him and the degeneration of their relationship: ‘I was 26 when you first drifted through the office in Union House, wearing one of your immaculately-fitted suits [….] And I, stupid fool, went weak at the knees, because I knew you couldn’t wait to get into bed with me. And then the dinners began, with the waiters bowing and scraping for the great Robert Haines. The plans we made over those dinners [….] And now, you come round here on Friday nights, like a nice Jewish boy dutifully visiting his mother on Golders Green. Well, I’m not lighting any more candles for you, you rotten, weak-kneed bastard’, Jean tells Haines, fed up with their relationship which, over ten years, has stagnated. Her comments cut to the quick of the appeal of his brand of power. However, Haines clearly has another bee in his bonnet, turning the conversation away from his relationship with Jean and towards the issue of political violence: ‘Listen. Just listen’, he protests when hearing the sirens of emergency vehicles outside; ‘My own city playing host to all manner of terrorist vermin, polluting everything with their foul ideas, destroying everything that’s decent and honest [….] Those people out there are intent on destroying everything that you and I hold dear’. ‘Such as?’ Jean challenges him. ‘Everything: order, rule of law’, Haines asserts. ‘Family life?’ Jean questions him sarcastically. Jean soon reveals that she has a surprise for Haines; but both Haines and Jean suffer a further surprise when Haines is brought to task for his association with ruthless foreign despots.

‘Crimes of Persuasion’ turns its studio-bound nature into a strength: the episode is remarkably claustrophobic. The episode is bogged down by the terribly stereotypical portrayal of the deposed prime minister of an unnamed Middle Eastern country, but is truly effective in notching up suspense as, first, Haines’ interview is crosscut with Jean’s encounter with Robinson and, later, as Haines conversation with Jean is intercut with shots of faceless shadowy figures, presumed terrorists who seem to move through the city like spectres, their silent actions (for example, the priming of a bomb) underscoring the fragmentation of relationships that is foregrounded in the dialogue. Without revealing too much, the climax of the episode brings together the themes of political violence and crimes of passion that are discussed in Haines’ interview with Jeremy Hope, deconstructing the dualism between the two that Haines’ comments creates. A taut, suspenseful and thematically rich episode, ‘Crimes of Persuasion’ is one of the highlights of this set.

Finally, ‘Truth or Consequences’ focuses on a young man, James White (David Robb). The episode opens with James waking up in bed with his partner Penny (Rosie Kerslake). James declares, ‘I’ll wear my suit, I think. Best to arrive looking smart’. He’s going away: a lieutenant in the navy, he has volunteered for a special training course, for which he has been given a folder filled with documents. After saying goodbye to Penny, James sets out on his journey. He stops at a roadside café: his car has broken down, and he is told by the mechanic that someone has put sugar in his petrol tank. An older man strikes up a conversation with James and offers him a lift. However, the older man seems to be taking notes on James, and after James has accepted the lift and deposited his suitcase in the older man’s car, the older man seeks the opportunity to sneak outside – unbeknownst to James – and go through James’ bags. Arriving at his destination, James finds himself chastised for smoking and arriving late. ‘It’s begun, has it?’, James asks. That night, he is tormented by sounds of loud banging in the hallways, which keep him awake. The place is run like a military barracks.

The next morning, James is reintroduced to the discipline of military life. The course is to prepare pilots for situations in which they may fall into the hands of enemy forces whilst flying experimental aircraft. The young man is told, by Commodore Jacobs (Stephen Murray), ‘You can stop it any time you wish [….] No-one will think any less of you if you do not complete’. He is questioned about the man who gave him a lift. ‘Intelligence chap’s in a bit of a spin’, he is told; ‘This chap who gave you a lift is known to Intelligence’.

Eventually, James is accused of passing on information to the man who gave him a lift. It seems that the man has Photostat copies of everything in the envelope James was given before he came to the course. With this in mind, James returns home, a broken man. In frustration, he beats his wife Penny. ‘What are they doing to you?’, she cries. James gets in a car and returns to the site of his course to sign a confession that he willingly passed on classified information to an enemy agent. ‘This is a lie […] because I know it to be the truth […] It is the truth that is a lie, or it is a lie that is the truth’, James asserts. A watchable episode, ‘Truth or Consequences’ is hampered by its reliance on a ‘twist’ ending that can be spotted a mile off. More interesting is the development of James’ character, from his social awkwardness in the working class roadside café to his final moment of hostility (‘Mind your own bloody business’) towards a fellow traveller on the train home. Throughout, James is a fish out of water; his military training even punctures his only sanctuary, his home life with Penny. One of the weaker episodes in the series, ‘Truth or Consequences’ nevertheless is never less than watchable. Disc One: ‘Easterman’ (51:47) ‘Killing’ (51:50) ‘The Great Albert’ (50:39) ‘The Ghost in the Pale Blue Dress’ (52:12) Disc Two: ‘Crimes of Persuasion’ (52:33) ‘Truth or Consequences’ (52:18) Gallery (4:46)

Video

All of the episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1. Most of the episodes are studio-bound and shot on video, with some filmed (16mm) location inserts. Picture quality is consistently good throughout all of the episodes. The original break bumpers are intact.

Audio

Sound is presented via a two-channel track, which is clear and unproblematic. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra feature is a gallery of still images on the second disk (4:46).

Overall

A good but inconsistent series, Scorpion Tales contains at least two gems: ‘Easterman’, whose strengths lie in Ian Kennedy Martin’s script and Trevor Howard’s powerhouse performance; and ‘Crimes of Persuasion’, which despite relying on some questionable stereotypes covers some very interesting thematic territory. ‘Killing’ and ‘The Great Albert’ are also very good. ‘The Ghost in the Blue Dress’ is arguably the weakest episode in this series, but it’s still watchable; both it and ‘Truth or Consequences’ could work better in a half hour slot rather than an hour long format. All of the episodes are consistently well-presented, although more contextual material would have been beneficial – especially considering the relative lack of literature about this particular series. The episodes should appeal to fans of 1970s anthology series. For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|