|

|

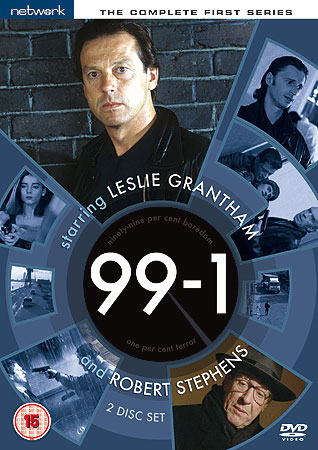

99-1 AKA 99 to 1: The Complete First Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th February 2011). |

|

The Show

99-1: The Complete Series One (Zenith Entertainment/Carlton, 1994)

Featuring some sparkling hard boiled dialogue, 99-1 (Zenith Entertainment/Carlton, 1994-5) offered a modern-day pastiche of film noir conventions that lasted for two series (of six and eight episodes, respectively). The series’ openly noir-ish narrative involves disgraced former detective Mick Raynor (Leslie Grantham) going deep undercover after being approached by high-ranking police official Commander Oakwood (Robert Stephens). However, towards the series’ end Raynor is left high and dry when Oakwood, his ‘handler’ and the only person who knows that Raynor is undercover rather than simply a ‘good cop turned bad’, is killed. The undercover cop was a staple of classic films noirs of the late-1940s – including The Street with No Name (William Keighley, 1948), The Undercover Man (Joseph H Lewis, 1949) and T-Men (Anthony Mann, 1947) – and later ‘neo-noirs’ such as Cruising (William Friedkin, 1980) and Reservoir Dogs (Quentin Tarantino, 1992); and a very similar situation was central to John Woo’s roughly contemporaneous noir-tinged action thriller Hard-Boiled, 1992, and would later form the locus of Wai-keung Lau and Alan Mak’s Hong Kong noir Infernal Affairs, 2002.

The first episode of 99-1, ‘Doing the Business’, opens with an aerial shot of the Thames that follows two limousines through the London Docklands. The limousines arrive at the headquarters of the Denison Group, where the occupants of the vehicles – a group of visiting Japanese dignitaries – are greeted by the Denison Group’s managing director, Andrew Denison. Whilst showing the visitors around the company’s new headquarters, the ‘jewel in the crown of Nightingale Wharf’, Denison discovers the body of a man hanging upside down on the building’s empty top floor. With this, the police are called, and Detective Inspector Mick Raynor (Leslie Grantham) arrives, accompanied by Detective Constable Trevor Prescott (Robert Carlyle). A walking bag of clichés, Raynor mouths a series of homilies intended to signify his authority and his status as a detective who relies on his instincts and is unfazed by the brutality on display at the crime scene (‘A murder like this isn’t just a murder: it’s a message. Find out who it’s for, and you’ll find out who it’s from’, Raynor declares as tracking shots are used to show Grantham’s ownership of the space through which he moves). This opening sequence establishes a strong time and place for the series – the redevelopment of the London Docklands – and seems to offer a subtle critique of the troubled Canary Wharf project, which was very much at the forefront of the popular imagination during the early 1990s. Meanwhile, Raynor is accused of falsifying statements in the case of convicted armed robber Derek Bilton, who has been released on appeal. ‘Did you fit him up?’, the chief superintendent asks Raynor before suggesting that Raynor should resign; Raynor displays another trait associated with the anti-heroes of films noirs when he insolently responds by asserting, ‘I’m not going to resign, and you try to make me the bad apple, and I’ll push the whole sodding barrel over’. Contributing to Raynor’s problems is his strained relationship with his ex-wife Charlotte (Gwyneth Strong) and his lack of contact with his young son Sam (Josh Maguire). Raynor’s fractured home life is foregrounded in a sequence in which Raynor returns home and, on his journey back, the viewer is presented with an abundance of shots of Raynor perfecting a thousand yard stare to rival that of Dana Andrews’ troubled detective Mark Dixon in Where the Sidewalk Ends (Otto Preminger, 1950). Andrews was an actor who brought to his noir performances an air of ‘tortured self doubt’ (Crowther, quoted in Spicer, 2002: 97); along with Glenn Ford, Wendell Corey and Edmond O’Brien, Andrews ‘could play the ordinary Everyman [sic] who […] is always enmeshed in circumstances beyond his control’ (ibid.). Andrews’ noir performances were characteristic of the shift in film noir from ‘the all-too-common hero of the postwar films, the maladjusted veteran, [who] was gradually replaced in the films of the early 1950s by an equally marginal figure, the rogue cop’ – replacing ‘one type of morally ambiguous protagonist [with] another who was perhaps more suitable to the times’ (McDonnell, 2007: 437). This heritage of films noirs’ depictions of the isolated, maladjusted ‘rogue cop’ seems to be what 99-1 is aiming for in its characterisation of its protagonist, Mick Raynor. On the soundtrack, Raynor’s journey home is accompanied by a morose and noir-ish trumpet-led piece of music. His answerphone at home contains a message from his ex-wife Charlotte: ‘If you want to see your son over the festive season, I suggest you should before he forgets what you look like’. Raynor resigns himself to watching It’s a Wonderful Life on the television whilst eating his Christmas dinner alone and drinking a large glass of neat Scotch.

However, Raynor’s lonely Christmas is interrupted by Prescott, who – with his girlfriend in tow – arrives at Raynor’s flat to ‘cheer you [Raynor] up before the ghost of Christmas past comes howling down your chimney’. Prescott and Raynor disagree when Raynor offers Prescott and his partner a drink of whisky, and Prescott recognises the bottle as being from a caseload that was stolen. Prescott chastises Raynor, reminding him that ‘It’s not a game. If you let them in, if you give just one inch of your integrity, they’ll take the lot’. Aware that Raynor is facing expulsion from the force over his handling of the Bilton case, Commander Oakwood offers Raynor a proposition, suggesting that he go ‘deep undercover [….] As deep as it goes. I want a man who isn’t afraid to get dirty or his fingers burnt [….] How about a disgraced ex-policeman, bitter’. Raynor would have to go undercover for a couple of years, with the aim of exposing high-profile figures who enable the activities of the criminal class: ‘The whole country’s bent, it’s endemic. I want the straight names who finance the graft, I want the companies who launder the proceeds, I want the gangsters with knighthoods’, Oakwood tells Raynor.

Following a tip, Prescott searches an abandoned building in an atmospheric sequence dominated by an expressionistic use of chiaroscuro lighting and primary colours. ‘Are you a copper?’, a young man asks and holds a gun to Prescott before killing him. Thanks in part to the appearance of Robert Carlyle, the scene is reminiscent of the sudden explosion of violence that ends the life of Detective Chief Inspector Billborough (Christopher Eccleston) in ‘To Be a Somebody’, the three-part story that opened the second series of Cracker (Granada, 1993-6, 2006). In both scenes, a policeman is killed whilst searching an apparently empty building, and the killer attacks from an unexpected corner of the room. (‘To Be a Somebody’ was first broadcast in October, 1994, and this first episode of 99-1 was broadcast in January of the same year.) After the murder of Prescott, Raynor’s disillusionment with the law grows and he accepts the undercover job offered to him by Commander Oakwood. ‘As a good guy, Raynor, you were rotten. As a villain, you’d better be pretty good’, Oakwood tells Raynor. In this first episode, in which Raynor is depicted as a maverick policeman, there is more than a hint of Dana Andrews’ performance as ‘rogue cop’ Mark Dixon in Where the Sidewalk Ends; Raynor shares Dixon’s bitterness, isolation and pessimism. It is a very film noir-like characterisation, but where Grantham seems slightly awkward in the procedural scenes depicting the investigation into the man found murdered in the Denison Group’s headquarters, he seems much more at home in the subsequent episodes, in which – as Raynor – he is asked to go deep undercover, adopting an underworld persona not dissimilar to ‘Dirty’ Dennis Watts, the character Grantham played in Eastenders (BBC, 1985- ). In these episodes, Raynor finds himself in conflict with Oakwood: where Raynor wants to take action to see the criminals he encounters brought to justice, Oakwood tells Raynor to bide his time in an attempt to catch the bigger fish. When, in the second episode, Raynor questions Oakwood’s management of the investigation (‘If I’m working for you, you don’t work against me… ever’, Raynor asserts), Oakwood reminds Raynor of the dangers inherent in Raynor’s role as an undercover agent: ‘Don’t annoy me, Raynor: I’m the only thing between you and the deep blue sea’, Oakwood declares.

The second episode establishes the thematic territory of the series in its titles sequence (the pilot episode featured no opening titles sequence), which is shot in high-contrast monochrome and features a mean and moody Grantham shot, via expressionistic canted angles and long shots that emphasise his isolation, in various urban locales. As Grantham walks through the city, a mournful trumpet-led piece of music fills the soundtrack. In a low-angle shot, Grantham discards his CID identification in a gesture that seems to allude to noir-influenced ‘rogue cop’ ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan throwing away his badge at the end of Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971) and, indirectly, the climax of High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952) – in which Gary Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane tosses his sheriff’s badge to the ground in front of the townsfolk who refused to help him confront the group of killers that threatened their community. As in Dirty Harry and High Noon, Raynor’s gesture signifies a disillusionment with the law and its processes, foregrounding the character’s ‘rogue cop’ status. This symbolic gesture is followed by a shot of Grantham descending a staircase, the image of a swaying lightbulb seemingly alluding to the iconic opening titles sequence of Callan (ABC, 1967-8; Thames, 1970-2). In the second episode, ‘The Hard Sell’, Raynor has to adjust to life in prison, and he also has to manage his relationship with his ex-wife and son – who are unaware that Raynor is working undercover. After attempting to prove that he has ‘gone bad’, by assaulting one of the prison guards, Raynor begins to make contacts in the underworld and, when released after six months in prison, is ordered by Oakwood to investigate the many tiers of corruption – including policemen, customs officials and bureaucrats – that are exploited by a drug dealer named Jerry McCarthy (Danny Webb). However, Raynor finds himself with enemies on both sides of the law, reminded by one of his cellmates in prison that ‘nothing stinks worse than a bent copper’. When Raynor approaches McCarthy and asks him for work, he is once again reminded that he is a pariah in both the criminal underworld and in respectable society: ‘Why should I take a risk with a bent copper?’, McCarthy sneers at Raynor. ‘All I want’s a chance to earn a decent living for once’, Raynor retorts. Later, in episode four, George Hicks (Derek Newark) reminds Raynor that he still has ‘copper’s eyes’ and asserts, simply, that ‘Filth never changes, my son’. From the opening moments of the first episode (which touch on the regeneration of the London Docklands that was taking place throughout the 1980s and 1990s), the series outlines the changing landscape of Britain. In the second episode, Raynor and a young associate, Phil Mitchell (Lee Ross), are sent by McCarthy to a quarry. ‘What are we doing here, men like us? We’re useful men, what are we doing this for’, Phil man asserts. ‘Made a right bloody mess of this, didn’t they? Used to be a bit of countryside here’, the younger man tells Raynor, reflecting on the abandoned quarry and the changing cultural landscape of Britain. Phil then expresses his own philosophy, which seems to chime with that of the series itself: ‘Just like everything else in life: if you can’t handle it, you’re gonna go under. No-one said it was going to be easy, did they’.

Subsequent episodes feature Raynor following other prey. As the series develops, moments of humour are introduced to lighten the tone (in ‘Trust Me’, the third episode, Grantham offers a bizarrely comic impersonation of Sean Connery) and Raynor’s undercover role also introduces him to a series of relationships with women – as his relationship with his ex-wife and son is mostly sidelined. In ‘Trust Me’, Raynor meets up with an old flame, Ronnie (Sharon Duce), who runs an upmarket brothel. (Raynor and Ronnie’s relationship is consummated in a clumsily-shot and awkward sex scene.) Raynor’s relationship with Ronnie allows the two characters to muse on the theme of aging: ‘I don’t think about the past much [....] It’s frightening, isn’t it? Being in the middle [….] I’m scared of getting old; I’m scared of not getting old’, Ronnie tells Raynor. (Elsewhere, in the fourth episode, ‘Where the Money Is’, Raynor is describes as a ‘Keen young thing, you were’ before being asked ‘What went wrong?’ ‘I got old’, Raynor replies.) However, Ronnie and Raynor’s relationship comes to an unhappy end when Raynor’s investigation brings the police to Ronnie’s doorstep, destroying her club’s reputation for discretion.

Disc One: ‘Doing the Business’ (51:02) ‘The Hard Sell’ (51:31) ‘Trust Me’ (51:34) ‘Where the Money Is’ (51:24) Disc Two: ‘Quicker than the Eye’ (51:33) ‘The Cost of Living’ (51:27)

Video

The episodes seem to have been shot on video, displaying the visual characteristics of the medium (weak contrast, burnt-out highlights). Presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3, the episodes make strong use of location shooting and thus have something of a ‘gritty’ appearance – comparable to the look of the Manchester-set Cracker.

The DVD presentation of the episodes contained in this set is very good, with all of the episodes displaying a crisp and clear image. The episodes’ original break bumpers are intact.

Audio

Audio is presented via a functional and clear two-channel stereo track. There are no subtitles.

Extras

None.

Overall

99-1 is a diverting series with some interesting themes (the changing face of Britain, the theme of middle age that runs throughout the episodes) which are undercut by some badly-handled moments (for example, the awkward blue-lit, soft-focus sex scene between Raynor and Ronnie in episode two, which plays out like an extract from Zalman King’s The Red Shoe Diaries; Showtime, 1992-7). The opening episode seems like a weak imitation of more contemporaneous procedural series such as Cracker, but 99-1 hits its stride with its second episode; and it seems that Grantham is much more comfortable playing Raynor as an undercover ‘rogue cop’ than as a card-carrying detective inspector. Whereas in the first episode, Grantham’s performance during the procedural scenes is stiff and unconvincing, in episode two – partly thanks to the moments of humour that make the character seem less dour and self-obsessed – Grantham’s performance becomes more naturalistic and, as the series progresses, he eases into the character. Grantham seems particularly at home delivering some of the excellent hard boiled putdowns that litter the series. (In episode two, Raynor is confronted by the doorman at Ronnie’s brothel, who asks Raynor if there is anything he can do for him; Raynor’s response is to assert that, ‘You could take your tongue out of my backside and tell Ronnie I’m here’.) The series offers a direct pastiche of the conventions of films noirs and, specifically, the ‘rogue cop’ subtype that grew out of the early 1950s and which influenced later films such as Dirty Harry. The same lineage is behind Jimmy McGovern’s Cracker, of which 99-1 sometimes seems to be a pale imitation. Whilst 99-1 gets a welcome DVD release, it is a shame that the more consistent The Paradise Club (Zenith Entertainment, 1989-90) (in which Grantham co-starred with Don Henderson) is still unavailable on home video. References McDonnell, Brian, 2007: ‘Where the Sidewalk Ends’. In: Mayer, Geoff & McDonnell, Brian (eds), 2007: Encyclopedia of Film Noir. ABC-CLIO: 437-8 Spicer, Andrew, 2002: Film Noir. Pearson Education For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|