|

|

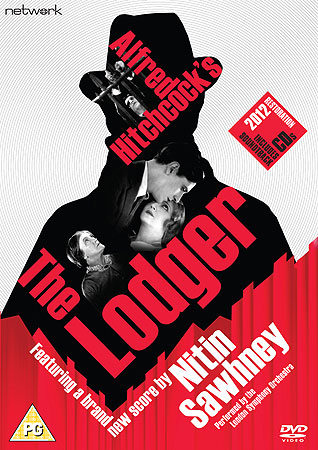

Lodger (The) AKA The Case Of Jonathan Drew AKA The Lodger: A Story Of The London Fog

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (2nd October 2012). |

|

The Film

The Lodger (Alfred Hitchcock, 1926)  In his study of Hitchcock’s first ‘talkie’, Blackmail (1929), Tom Ryall asserts that Hitchcock’s films of the 1920s were ‘a medley of theatrical and literary adaptations’ (1993: 9). Ryall asserts that Blackmail, Hitchcock’s tenth film as director, ‘was only the second of his films to incorporate those elements of the “Hitchcockian” universe we now take for granted’ (ibid.). The first of those films was, of course, Hitchcock’s now-classic silent thriller The Lodger or, to give the film its full title, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1926). For Ryall, both The Lodger and Blackmail foreground their ‘debt to the dark, obsessive world of the German silent film’, presenting their narratives through expressionistic visuals (ibid.: 44-5). In his study of Hitchcock’s first ‘talkie’, Blackmail (1929), Tom Ryall asserts that Hitchcock’s films of the 1920s were ‘a medley of theatrical and literary adaptations’ (1993: 9). Ryall asserts that Blackmail, Hitchcock’s tenth film as director, ‘was only the second of his films to incorporate those elements of the “Hitchcockian” universe we now take for granted’ (ibid.). The first of those films was, of course, Hitchcock’s now-classic silent thriller The Lodger or, to give the film its full title, The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1926). For Ryall, both The Lodger and Blackmail foreground their ‘debt to the dark, obsessive world of the German silent film’, presenting their narratives through expressionistic visuals (ibid.: 44-5).

The Lodger was based on a 1913 novel by Marie Belloc-Lowndes and filmed at Islington Studios. The film was apparently criticised by Graham Cutts, one of the key British film directors of the 1920s and, for a while, Hitchcock’s mentor during his early years at Gainsborough Pictures. Cutts’ criticism of the film led to producer Michael Balcon delaying its release. The film was re-edited slightly and, upon its eventual release, proved to be a success with the public. In response, in the words of Edward Maxford, Cutts ‘left Gainsborough, angered at being usurped by Hitchcock as the company’s top director’ (2002: 144).  The film opens bravely, with a close-up of a woman screaming before a cut to an onscreen title: ‘To-Night: Golden Curls’. The title card is presented without context and reappears throughout the film; it has a double meaning, referring both to the stage show in which Daisy Bunting (June Howard Tripp) is appearing, and the killer’s preference for blonde-haired young women. A shot of the screaming woman’s dead body follows, carrying the iconography of crime scene photography. A shot of an elderly female witness follows, and then we are shown a policeman writing in his notebook as well as shots of a crowd gawping at the body. The policeman bends down, finding a note on the body. The note reads simply, ‘The Avenger’. The film opens bravely, with a close-up of a woman screaming before a cut to an onscreen title: ‘To-Night: Golden Curls’. The title card is presented without context and reappears throughout the film; it has a double meaning, referring both to the stage show in which Daisy Bunting (June Howard Tripp) is appearing, and the killer’s preference for blonde-haired young women. A shot of the screaming woman’s dead body follows, carrying the iconography of crime scene photography. A shot of an elderly female witness follows, and then we are shown a policeman writing in his notebook as well as shots of a crowd gawping at the body. The policeman bends down, finding a note on the body. The note reads simply, ‘The Avenger’.

‘Tall he was – and his face all wrapped up’, the elderly woman declares. With this, we see a glimpse of Hitchcock’s black humour, a recurring feature of his later work: as the elderly woman makes this statement, a man in the crowd wraps his face in his coat. The crowd berate him. Meanwhile, at the theatre where Daisy performs, the women are shown in the changing room. They are happy and jovial. The women find out about the murder. ‘He’s killed another fair girl’, one of the women says. ‘No more peroxide for yours truly’, another declares. Before leaving, the women cover their hair with hats. Later, Daisy’s friend Joe (Malcolm Keen), a policeman, arrives at the house where Daisy lives with her parents (Arthur Chesney and Marie Ault). The titular lodger (Ivor Novello) also arrives, looking for a room to rent. As the narrative develops, the lodger develops a bond with Daisy, much to the dismay of Joe. Meanwhile, Mr and Mrs Bunting begin to suspect that their new lodger may in fact be the Avenger. Hitchcock noted that The Lodger ‘was the first time I exercised my style. In truth, you might almost say that The Lodger was my first picture… I took a pure narrative and, for the first time, presented ideas in purely visual terms’ (Hitchcock, quoted in Maxford, op cit.: 144). Certainly, The Lodger covers some thematic territory that would become characteristic of Hitchcock’s later thrillers: the ‘wrong man’ who is accused of a crime; a key character who, like Norman Bates in Psycho (1960), challenges audience identification; voyeurism and scopophilia (Daisy’s work in ‘Golden Curls’ makes her the object of the male gaze, as a sequence which depicts the lodger visiting her place of employment makes clear); the blonde-in-peril (June Tripp was the second actress Hitchcock persuaded to dye her hair blonde, following in the footsteps of Virginia Valli in the 1925 film The Pleasure Garden); and The Lodger was the first of Hitchcock’s films to feature one of his trademark cameos.  Hitchcock stages a number of bravura set-pieces that draw on the iconography of German Expressionism: the opening sequence depicting the aftermath of one of the Avenger’s murders is a highlight, as is the famous scene in which the Buntings listen to the lodger pacing his room – a moment depicted in a low-angle shot of the ceiling of the Bunting’s living room, which dissolves to a shot taken below a glass floor on which Ivor Novello paces backwards and forwards. Hitchcock stages a number of bravura set-pieces that draw on the iconography of German Expressionism: the opening sequence depicting the aftermath of one of the Avenger’s murders is a highlight, as is the famous scene in which the Buntings listen to the lodger pacing his room – a moment depicted in a low-angle shot of the ceiling of the Bunting’s living room, which dissolves to a shot taken below a glass floor on which Ivor Novello paces backwards and forwards.

Opening with the BBFC logo, the film runs for 87:09 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The disc contains the new restoration of The Lodger by the BFI, in association with Network, ITV Studios and Park Circus Films. Visually, the new transfer represents an improvement over the previously-available DVDs, although it pales in comparison with some other releases of silent films (for example, Eureka’s releases of F W Murnau’s Sunrise and City Girl). Nevertheless, the new restoration adds visual clarity to a film that, in previous home video incarnations, has predominantly had a ‘murky’ appearance. The new restoration also apparently restores the film’s original tinting.

Audio

The new restoration of The Lodger is accompanied by a newly-composed score, written by Nitin Sawheny and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. For the most part, the score works very well, and at times Sawheny seems to allude to some of Bernard Herrman’s iconic scores for Hitchcock’s later films. However, the new score also incorporates two songs, which are likely to divide opinion. Some may see them as distracting and out of place, whereas others may claim that the new songs underscore the emotional content of the film.

Extras

The disc contains a featurette, ‘Scoring The Lodger with Nitin Sawheny’ (19:03). In this featurette, Sawheny discusses his musical background and the circumstances which led to him composing a new score for The Lodger. Sawheny clearly has an interest in Hitchcock’s work, and his enthusiasm for the films shines through. Sawheny also talks about how he approached the task of composing a new score for the film. He reflects on his collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra. Sawheny provides a detailed, fascinating discussion of the main themes that can be heard in his new score. Further to the featurette, the disc includes a stills gallery (2:12) of posters, production photographs and promotional stills from the film.

Overall

The Lodger is an excellent film, a pivotal picture in Hitchcock’s body of work. This new restoration is very satisfying for a long-time fan of the film: it improves upon the largely ‘murky’ transfers that have circulated in the past, offering a clarity of image that is appealing and allows previously hidden details to leap out at the viewer. The restoration of the film’s original tinting is another strength of this release. Sawheny’s newly-composed score complements the film well. However, the two songs that are included in the score are likely to divide opinion. This new restoration is also available on Blu-ray. References Maxford, Edward, 2002: The A-Z of Hitchcock. London: B T Batsford Ryall, Tom, 1993: BFI Film Classics: ‘Blackmail’. London: British Film Institute For more information, please visit the homepage of Network. This review was kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|