|

|

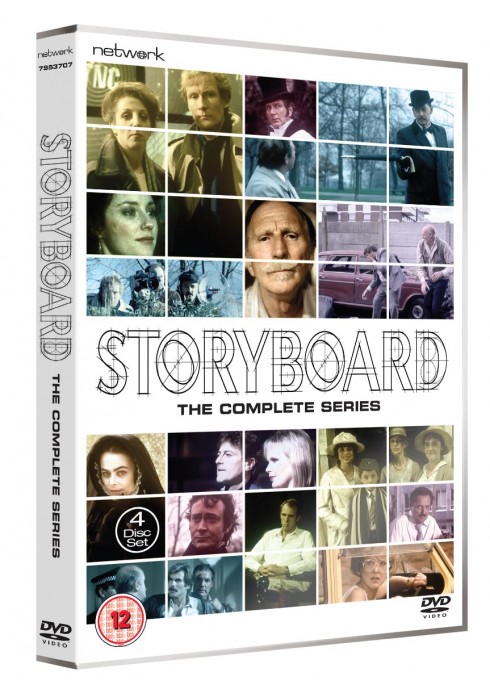

Storyboard: The Complete Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th February 2013). |

|

The Show

Storyboard (Thames, 1983-8)

On the other hand, during the 1990s there was an increasing perception of the single play format as ‘elitist’, and amongst critics and producers there was a perception that ‘[t]he present market-led era where soap opera, fly-on-the-wall docu-drama and interchangeable crime and hospital series reign supreme is, they say, more democratic and more what the audience wants’ (ibid.: 253-4). Commenting in 1981, only several years before the production of Storyboard – which in some ways may be considered the ‘last gasp’ of ITV’s last single play series – George W Brandt observed that in the US, ‘the single play has virtually been killed off to make way for machine made series and serials with high gloss, canned laughter and routine violence’ (22). Brandt noted that the ‘threat to the single play is primarily economic: an easily marketable product is an attractive proposition if ratings or overseas sales appeal are the programme executives’ prime motivations’ (ibid.). In addition, where the single play strand could sometimes prove to be incendiary (or at least controversial) in its content, ‘[d]rama content is more controllable in the series format with its narrow guidelines laid down for the writer or writers. At times when the “message” play can stir up hornets’ nests of letter-writing pressure groups, retreating to the safety of story-edited, prepackaged drama may seem an easier option’ (ibid.). Audience loyalty for ‘prepackaged drama’ is also much easier to build up than for single play strands, due to the continuity of theme, narrative and character that characterise dramatic series (and serials) (Brandt, 1993: 15-6). At the turn of the 1980s, the BBC’s then-Head of Drama, Shaun Sutton, observed that the single play strand was ‘the life-blood of drama’, asserting that ‘[i]f you have a total output of series only, crime series, social series and all the rest of it, however good they are, you would be seeing one sort of drama of the same length, all very careful not to offend or overstep any social barriers (Sutton, quoted in Brandt, 1981: 22). Where single plays were ‘less subject to management interference’, they offered one of ‘the best vehicle[s] for asking awkward social questions’, which along with declining audience figures may account for the single play form’s ‘diminution during the Thatcher era’ (Brandt, 1993: 15). Of course, the single play format has made something of a return in recent years, in a slightly revised form, as shown by series like The Street (BBC, 2006- ) and Accused (BBC, 2010- ). However, by the time of the production of Storyboard in the mid-1980s it was a dying form. This may be read in the way in which two episodes of storyboard, ‘King and Castle’ and ‘Woodentop’, effectively functioned as ‘pilots’ of two ITV series: the fondly-remembered King and Castle (Thames, 1986-8) was relatively short lived, running only for two series; ‘The Traitor’ and ‘A Question of Commitment’ focus on ‘spycatcher’ Palfrey (Alec McCowen), who would later feature in the series Mr Palfrey of Westminster (Thames, 1984-5); and ‘Woodentop’ evolved into The Bill (Thames/ITV Studios, 1984-2010), which along with Taggart (STV, 1983- ) remains one of the UK’s longest running police dramas.  One of the pleasures of the single play strand is the diversity of its content: from one week to the next, a single play strand may feature a diverse range of storylines, characters, themes and personnel. On the other hand, this can also lead to an inconsistency in terms of quality. Storyboard is a strong example of this. Some of the stronger episodes have much in common with the socially provocative single plays of earlier eras. For example, ‘Judgement Day’ (written by James Doran) focuses on the conflict between the law and concepts of justice. This conflict is dramatised through the collision of the values of Rook (Tony Steedman), a Crown Prosecutor with a ‘softly-softly’ approach to juvenile offenders (‘With juveniles, it’s not simply a case of processing people for punishment; one has to look carefully at these children and do what one can for them’), and his higher-ups who describe the police – who frequently complain about Rook due to a perception that he is a ‘soft touch’ – as their ‘clients’, suggesting that they must be pleased at all costs. This conflict is seen through the eyes of Jane Alexander (Carol Royle), who has been drafted in to replace Rook. Reflecting on the attitude of one of the policemen, Rook tells Jane that he misses ‘the old fashioned Bobby that knew his place’. ‘The Dixon of Dock Green type; did they ever exist?’, Jane asks. ‘Yes, they’re gone now, along with so much that had style and dignity’, Rook reflects. Later, he tells Jane that their bosses insist on ‘prosecuting cases that should not be prosecuted’. When Jane responds by stating that they only want to make the department the best in the country, Rook tells here, ‘You are young, Miss Alexander, and enthusiastic; I am neither’. The acclaimed ‘Woodentop’ is another example of a television play that looks backwards to the socially-minded single plays of the 1950s and 1960s. The Bill would later depict a conflict between two methods of policing: the depiction of policing as a form of pastoral care, embodied in the uniformed police officers (as per Dixon of Dock Green; BBC, 1955-76); and the representation of policing as a form of social control, embodied in the plainclothes detectives (as per The Sweeney; Thames, 1974-8). Frequently in The Bill, the uniformed police officers would be in conflict with the plainclothes detectives (please see our reviews of The Bill Volumes Two and Three); these conflicts would offer a dialogue between two different ideas of what policing is and what it should strive to be. This conflict is already present in ‘Woodentop’, as the young PC Carver (Mark Wingett) begins his first day at Sun Hill and is partnered with June Ackland (Trudie Goodwin) and Dave Litten (Gary Olsen) - who have markedly different ideas about their roles as uniformed police officers - and witnesses the conflicts between the CID men (who refer to the uniformed coppers as ‘woodentops’) and the uniformed officers (who sarcastically label the CID men as ‘bloody superstars’). Geoff McQueen’s script has an authenticity to its situations and language that was carried over into the first three series of The Bill. Some episodes offer dramatisations of existing narratives: ‘Inspector Ghote Moves In’ is based on the Inspector Ghote series of stories written by H R F Keating (and features Sam Dastor as Ghote). The episode is interesting inasmuch as it was produced at a time when British television began using non-white actors as the leads in crime series: in 1981, British television saw its first black detective (played by George William Harris), in the controversial Wolcott (ATV); and in the same year, Ian Kennedy Martin created the more warmly-received BBC drama The Chinese Detective (1981-2), in which the title role was played by David Yip. This trend had been anticipated slightly by the BBC’s 1970s series Gangsters (1975-8), which was set in multi-cultural Birmingham and featured as one of its central characters an undercover British Asian detective, Khan (Ahmed Khalil).  In ‘Inspector Ghote Moves In’, Inspector Ghote (of the Bombay CID) is invited by Scotland Yard to observe its methods. Staying with Colonel Bressingham (Alfred Burke) and his wife, Ghote becomes embroiled in a mystery. Along the way, Ghote faces prejudice, both implicit (Bressingham spent time in India and patronises Ghote, referring to him as ‘a police-wallah’) and explicit: when the Bressinghams appear to be the victims of a theft, Ghote faces outright prejudice from the detective investigating the crime. ‘When did you leave Pakistan?’ the detective asks Ghote accusingly. ‘It is from India I am’, Ghote informs him, eventually coming up trumps when he reveals that he is from Bombay CID and has been formally invited to England by Scotland Yard. Elsewhere, the director Peter Duguid shows a stylish handling of the material as, at night, Ghote hears Bressingham ranting and goes to investigate, witnessing the Colonel prowling through the house with his rifle in his hands. The scene is shot expressionistically, with heavy red gels on the lights, making it seem like a scene from a Mario Bava horror film. The final episode, ‘Hunted Down’ is also an adaptation of an existing story (in this case, by Charles Dickens) and in its opening scene features an interesting breakage of the fourth wall: whilst a party takes place in the background Alec McCowen, as Sampson, addresses the audience directly, informing us that he will ‘tell you a story that begins where others end: in a graveyard’. Other episodes are less successful: ‘Lytton’s Diary’, written by Ray Connolly, focuses on a journalist (Peter Bowles) who writes a gossip column, eventually running into a spot of bother when he slanders a politician, Jonathan Burridge (Ralph Bates). ‘Lytton’s Diary’ engages with the ethics of the press, but coasts by on the charm of Peter Bowles; in its focus on the ethical issues involved in the production of a gossip column, the episode strives to emulate The Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957) but is ultimately too mannered.  Likewise, ‘Secrets’ focuses on Miles Longstreet (John Castle), a Lothario and ‘security expert’. The episode explores the roles of ‘alpha males’ (‘Whatever became of men?’ one female character laments: ‘Nowadays they’re either queer and kinky or furtive and married’) and features a cleverly-written scene in which Longstreet has a conversation with a photographer, who insists on interrupting the dialogue in order to assert the shutter speed and f-stop of the image he and Longstreet happen to be looking at. On the whole, ‘Secrets’ is nicely-directed and acted but doesn’t really go anywhere. Similarly, ‘Snakes and Ladders’ (written by Jeremy Burnham) wears its Thatcher-era vintage on its sleeve, in its narrative of warring builders firms and striking workers. However, the characters are so flat and bullish that it’s difficult to become engaged by the material. DISC ONE: ‘Inspector Ghote Movies In’ (52:03) ‘Judgement Day’ (52:19) ‘Secrets’ (52:58) ‘Woodentop’ (49:35) DISC TWO: ‘The Traitor’ (52:31) ‘Lytton’s Diary’ (51:34) Special Feature: ‘Singles Night’ (52:39) DISC THREE: ‘King and Castle’ (53:17) ‘Ladies in Charge’ (52:09) ‘Thank You, Miss Jones’ (52:55) DISC FOUR: ‘Making News’ (52:27) ‘Snakes and Ladders’ (51:33) ‘A Question of Commitment’ (50:34) ‘Hunted Down’ (49:45)

Video

All of these episodes are presented in colour. They are all shot on video and display the characteristics of that form (burnt highlights, weak contrast, etc); they are also mostly studio-bound. For the most part, the tapes are in good condition, with some intermittent wear and tear. The episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3; break bumpers are intact.

Audio

Audio is presented via a functional and clear two-channel stereo track. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is ‘Singles Night’, included on disc two. Written by Eric Chappell, the creator of Rising Damp (Yorkshire Television, 1974-8) and Home to Roost (Yorkshire Television, 1985-90), ‘Singles Night’ was broadcast in 1984; three years later, it formed the basis of Chappell’s sitcom Singles (Yorkshire Television, 1988-91). Taking place in a hotel, it is essentially a comedy of manners that focuses on the interactions of a group of characters at a singles night.

Overall

One of the great strengths of the single play strand is its diversity: within the single play strand, writers can focus on an infinite range of narratives unencumbered by the need for continuity in narrative, theme, character, setting and authorial voice. Storyboard is no exception to this rule. On the other hand, this can result in inconsistent quality, and this is also evident within Storyboard. On the whole, it’s a very good series, and there are some outstanding episodes (‘Woodentop’, ‘King and Castle’ and ‘Making News’ are arguably the best); but conversely, there are also some instalments that lack direction or at times seem slightly self-indulgent. Nevertheless, Storyboard was one of the last gasps of the traditional single play format, and is fascinating because of this. This release contains good presentations of the episodes but, ‘Singles Night’ aside, little in way of contextual material. References: Brandt, George W, 1981: ‘Introduction’. In: Brandt, George W, 1981: British Television Drama. Cambridge University Press: 1-35 Brant, George W, 1993: British Television in the 1980s. Cambridge University Press Shubik, Irene, 2001: Play for Today: The Evolution of Television Drama. Manchester University Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|