|

|

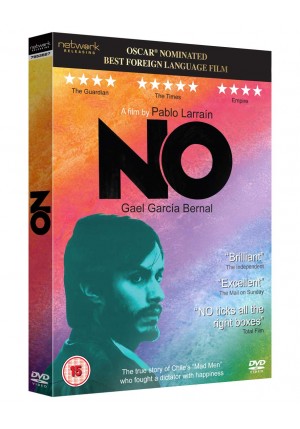

No

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th June 2013). |

|

The Film

No (Pablo Larrain, 2012)  No is director Pablo Larraín’s third film dealing with the effects of Pinochet’s regime in Chile: set in 1978, Tony Manero (2008, reviewed here) dealt with the social and cultural impact of Pinochet’s dictatorship, whilst Post Mortem (2010, reviewed here) focused on the 1973 coup that ended Salvador Allende’s government and put Pinochet in power. No examines the end of Pinochet’s reign, taking place in the run-up to the 1988 referendum that led to the ousting of Pinochet and the return of democracy to the country. Where both Tony Manero and Post Mortem shared the same lead actor, Alfredo Castro as, respectively, the 52 year old Saturday Night Fever-obsessed Raúl Peralta and the lonely, unexceptional civil servant Mario Cornejo, No focuses on a much younger protagonist: thirty-something advertising executive René Saavedra (Gael García Bernal). Saavedra, father to a young son, is offered the opportunity to oversee the ‘NO’ campaign: Chile’s citizens are being asked to vote simply YES or NO to Pinochet’s regime, and both the YES and the NO campaigns are to be given 15 minutes of television time per day. However, Saavedra’s boss, Lucho Guzmán (Alfredo Castro), is an advisor to Pinochet’s government and is given the task of heading the YES campaign. No is director Pablo Larraín’s third film dealing with the effects of Pinochet’s regime in Chile: set in 1978, Tony Manero (2008, reviewed here) dealt with the social and cultural impact of Pinochet’s dictatorship, whilst Post Mortem (2010, reviewed here) focused on the 1973 coup that ended Salvador Allende’s government and put Pinochet in power. No examines the end of Pinochet’s reign, taking place in the run-up to the 1988 referendum that led to the ousting of Pinochet and the return of democracy to the country. Where both Tony Manero and Post Mortem shared the same lead actor, Alfredo Castro as, respectively, the 52 year old Saturday Night Fever-obsessed Raúl Peralta and the lonely, unexceptional civil servant Mario Cornejo, No focuses on a much younger protagonist: thirty-something advertising executive René Saavedra (Gael García Bernal). Saavedra, father to a young son, is offered the opportunity to oversee the ‘NO’ campaign: Chile’s citizens are being asked to vote simply YES or NO to Pinochet’s regime, and both the YES and the NO campaigns are to be given 15 minutes of television time per day. However, Saavedra’s boss, Lucho Guzmán (Alfredo Castro), is an advisor to Pinochet’s government and is given the task of heading the YES campaign.

Whereas Tony Manero was openly allegorical, Peralta’s mental deterioration, his random violence and his obsession with American culture functioning as a metaphor for the Pinochet regime, both Post Mortem and No are more ‘concrete’ pictures about Pinochet’s dictatorship. No establishes its narrative territory immediately with a title card that tells us, ‘In 1973 Chile’s armed forces staged a coup against President Salvador Allende and General Augusto Pinochet took control of the government. After 15 years of dictatorship, Pinochet faced increasing international pressure to legitimize his regime. In July 1988, the government called a referendum. The people would vote YES or NO to keep Pinochet in power for another 8 years. The election campaign would last 27 days, with 15 minutes of television advertising every day for YES and 15 minutes for NO’.  As the film opens, Saavedra is shown in a boardroom presenting to a group of clients. ‘We believe that the country is prepared for communication of this nature’, he asserts: ‘We must not forget that the citizens have raised their demands in regard to truth, in regard to what they like. Let’s be honest: today, Chile thinks in its future’. However, although the viewer may be forgiven for thinking that the film has begun in media res, after Saavedra has been offered the task of organising the NO campaign, this is not the case: pressing play on a videotape editing machine, Saavedra is revealed to be introducing a television advertisement for a Coca Cola-style soft drink which is named ‘Free’. (The name of the soft drink is of course ironic, given the lack of freedom within Chile.) ‘This is everything that our youth needs: music, rebellion, romance. But with order and respect’, Guzmán tells the panel. As the film opens, Saavedra is shown in a boardroom presenting to a group of clients. ‘We believe that the country is prepared for communication of this nature’, he asserts: ‘We must not forget that the citizens have raised their demands in regard to truth, in regard to what they like. Let’s be honest: today, Chile thinks in its future’. However, although the viewer may be forgiven for thinking that the film has begun in media res, after Saavedra has been offered the task of organising the NO campaign, this is not the case: pressing play on a videotape editing machine, Saavedra is revealed to be introducing a television advertisement for a Coca Cola-style soft drink which is named ‘Free’. (The name of the soft drink is of course ironic, given the lack of freedom within Chile.) ‘This is everything that our youth needs: music, rebellion, romance. But with order and respect’, Guzmán tells the panel.

With this clever sequence, Larraín deftly introduces several strands within the narrative of No: Saavedra’s ability with rhetoric is foregrounded in his opening speech, which also establishes his idealism – which makes him the perfect candidate for the NO campaign. This is placed in juxtaposition with Guzmán’s more conservative assertion that the advertisement offers ‘everything our youth needs: music rebellion, romance’ but within a framework of ‘order and respect’; this juxtaposition foregrounds the way in which, later in the film, Guzmán and Saavedra are placed on opposite sides of the referendum: Saavedra allied with the opposition to Pinochet, and Guzmán offering his services to the YES campaign. With the close-up of Saavedra’s hand as he presses ‘play’ on the video editing machine, the film’s opening sequence also establishes the temporal setting of the film: an era of analogue television and videotape, foregrounded by Larrain's decision to shoot No using an outdated U-matic video camera. From the outset, the NO campaign seems doomed to failure. Saavedra meets with Urrutia (Luis Gnecco), a communist, who offers Saavedra the job of overseeing the NO campaign. However, Saavedra is initially sceptical, asserting that the referendum is only being carried out because Pinochet’s regime was under pressure to introduce it, and the election will be fixed in favour of Pinochet: ‘People either vote for Pinochet or they won’t vote at all’, he tells Urrutia. When Saavedra elects to accept Urrutia’s proposition, orchestrating the NO campaign, he encounters similar resistance from the people he attempts to recruit, and the film offers an almost didactic exploration of people’s attitudes towards the plebiscite. Saavedra’s ex-wife, Verónica (Antonia Zeggers), who has taken part in demonstrations against the Pinochet regime, asks Saavedra why he has accepted the task of organising the NO campaign: ‘You’re going to validate Pinochet’s fraud’, she says.  Meanwhile, it’s clear that in order to win, the NO campaign must overcome people’s fears of voting under Pinochet’s military junta. One of the NO campaign's early television advertisements includes a montage depicting the brutality of the Pinochet regime. Protesters are fired upon; tanks roll through the streets. ‘2110 Pollitical Executions. 1248 Disappeared Detainees’, the onscreen titles say. Saavedra shows the advert to a focus group, asking if he should produce ‘something a little nicer’. ‘Comrade, do you think what’s going on in Chile is nice?’, a young woman asks him. ‘The main objective is to open up the eyes of those who don’t want to vote’, another man says. ‘This plebiscite is lost from the moment that the fascist right called the vote’, the woman says. The protagonist questions why they should work on the campaign; the woman tells him that it’s important to raise awareness of the real facts of the Pinochet regime. Meanwhile, it’s clear that in order to win, the NO campaign must overcome people’s fears of voting under Pinochet’s military junta. One of the NO campaign's early television advertisements includes a montage depicting the brutality of the Pinochet regime. Protesters are fired upon; tanks roll through the streets. ‘2110 Pollitical Executions. 1248 Disappeared Detainees’, the onscreen titles say. Saavedra shows the advert to a focus group, asking if he should produce ‘something a little nicer’. ‘Comrade, do you think what’s going on in Chile is nice?’, a young woman asks him. ‘The main objective is to open up the eyes of those who don’t want to vote’, another man says. ‘This plebiscite is lost from the moment that the fascist right called the vote’, the woman says. The protagonist questions why they should work on the campaign; the woman tells him that it’s important to raise awareness of the real facts of the Pinochet regime.

At a meeting, Saavedra is forced to concede that ‘fear increases the number of undecided voters’, and many people will be afraid to vote NO. Many of these are middle class women: later, such a woman, who is preparing to vote YES, tells Saavedra that the ‘issue of the dead, the tortured, the disappeared’ is all in the past. On the other hand, the young people simply ‘think that this election is fixed, that it’s useless’, Saavedra says. Saavedra’s associates decide that they must find some way of making the NO campaign attractive to middle class women and young people. Meanwhile, at a committee meeting for the YES campaign, attended by Guzmán, the NO campaign is also represented as hopeless. One of the men says that the NO campaign will have only ’15 minutes of screen time divided between a bunch of different opinions, lost in the middle of the night. That’s what the opposition’s going to have. The YES campaign will have those fifteen minutes and the rest of the remaining time as well’. ‘Everyone wants a Pinochet’, he says, suggesting they should plaster Pinochet’s face all over the media and write an anthem. ‘We should take advantage of his blue eyes, his smile’, another man suggests: ‘If we want to scare people, scare them with their past’, reminding them of poverty and ‘the endless lines for bread’ that characterised the last years of Allende’s presidency. However, Saavedra’s camp is split. ‘Regarding human rights, exile, injustice [….] We haven’t approach it at all. It needs to be included’, some of them believe. Several within Saavedra’s group think that the campaign needs to foreground the suffering that the Chilean people have experienced under the Pinochet regime. However, Saavedra decides instead that the campaign needs to push the abstract concept of happiness and hope for the future. The group also begin to worry that their work for the NO campaign may result in them being placed in jail. During one meeting with Guzmán, Saavedra begins to realise the potential severity of his situation. ‘Look, you live an easy life with your son, man’, Guzmán tells him: ‘No one has laid a finger on you since you got here, man. Let’s be partners’, he says, trying to tempt Saavedra away from the NO campaign. ‘This is suicide’, Guzmán concludes: ‘Don’t be an idiot’. The reality sinks in for Saavedra when, one night, he finds his car vandalised and a car full of men waiting threateningly outside his home.  >At home, Saavedra watches the fifteen minute YES campaign, which romanticises Pinochet and consists of a series of images of the man with a solemn narration, underscored by some music and followed by an anthem celebrating Pinochet’s regime. Saavedra decides to combat this with a positive campaign. In one television advertisement, a man sings a folk song on the audio track whilst people celebrate. However, Saavedra faces resistance to this campaign. One of Saavadre’s colleagues stands up, unhappy with the advertisement. ‘This is a masquerade’, the man asserts, believing that the campaign is designed to draw attention away from the suffering endured by the Chilean people under Pinochet. Likewise, Verónica suggests the campaign, which has taken the image of a rainbow as its emblem, is infantilising. ‘We’re going to win’, Saavedra asserts. ‘Sure’, Verónica replies sarcastically. >At home, Saavedra watches the fifteen minute YES campaign, which romanticises Pinochet and consists of a series of images of the man with a solemn narration, underscored by some music and followed by an anthem celebrating Pinochet’s regime. Saavedra decides to combat this with a positive campaign. In one television advertisement, a man sings a folk song on the audio track whilst people celebrate. However, Saavedra faces resistance to this campaign. One of Saavadre’s colleagues stands up, unhappy with the advertisement. ‘This is a masquerade’, the man asserts, believing that the campaign is designed to draw attention away from the suffering endured by the Chilean people under Pinochet. Likewise, Verónica suggests the campaign, which has taken the image of a rainbow as its emblem, is infantilising. ‘We’re going to win’, Saavedra asserts. ‘Sure’, Verónica replies sarcastically.

When Guzmán he shows the rainbow emblem to one of Pinochet’s ministers, the minister comments, ‘A rainbow? But that’s for faggots, no?’ Guzmán corrects the minister, telling him, ‘No, I think it has to do with the flag of the Mapuche people’. (The Mapuche are a group of people within southern Chile, who sometimes use the Whipala flag, a rainbow-like pattern in which all of the colours are intended to represent the various indigenous groups of the Andes.) The campaign focuses on the theme ‘Happiness is coming’, and Saavedra’s crew record a song for the campaign (‘I don’t like it, no/I don’t want it, no’) which plays over a montage of the personnel shooting scenes for the television ads. The campaign seems to work: at a meeting of the ministers, Guzmán hears that Pinochet has been ‘personally offended’ by the NO campaign, and Guzmán notes that ‘We can’t fight universal principles like happiness or that stupid rainbow with a film about fruit exports’, adding that ‘We have to work on one axis: who is capable of governing and who is not capable of governing’. Guzmán also attempts to discredit the NO campaign by claiming that Saavedra’s interviewees are paid actors. Eventually, the NO campaign is censored: a federal judge who was prepared to discuss the use of torture by the Pinochet regime is forbidden from appearing onscreen. This becomes a major news story and galvanises people’s discontent with Pinochet. Ultimately, although it initially seems like the YES campaign is successful, the votes are recounted and Pinochet is ousted. Saavedra’s campaign has been a success, and Chile prepares for a wave of change. The film is uncut and runs for 112:59 mins (PAL).

Video

The film, part of a wave of films that have revived the traditional square-ish Academy format (along with Xavier Dolan’s Laurence Anyways, 2012, and Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights, 2011), is presented in its original screen format of 1.33:1.

The film was shot on a vintage 1983 U-matic video camera. The film thus has a very interesting aesthetic which carries the characteristics of shot-on-video material (burnt-out highlights, ghosting, etc). By shooting the film on video, Larraín was able to seamlessly integrate montages of actual newsreel footage with the main body of the film. It’s an ambitious experiment, especially in the age of HD video, but it works wonderfully.

Audio

Audio is presented via a choice of a two-channel stereo track or a 5.1 Dolby Digital surround track. Both of these are fine ways to view the film: the 5.1 track is a little more immersive, making some good use of the soundscape of the surround sound format, but it is by no means a ‘showy’ surround track. English subtitles are burnt-in.

Extras

There is a wealth of contextual material, including ‘Behind the Scenes’ featurette (5:10) UK Press Junket with Pablo Larrain (in English) (19:54) 56th BFI London Film Festival Q&A with Pablo Larrain (in English) (19:33) UK Screening Q&A with Gael Garcia Bernal and Eugenio Garcia (in English) (22:23) Amnesty International UK Interview with Gael Garcia Bernal (in English) (6:14) Theatrical Trailer (1:31) Stills Gallery (1:52) Bonus Trailers (which play on start-up and are skippable): Tony Manero, Post Mortem, the Xavier Dolan La Folie D’Amour boxset (containing I Killed My Mother, Heartbeats and Laurence Anyways) and Bonsai.

Overall

No is a stunning picture, a fitting conclusion to Larraín’s trilogy of films about Pinochet’s regime. The decision to shoot the film on a U-matic video camera was inspired and brave, and it works wonderfully. I’ve long held that Larraín is one of the most interesting filmmakers working today, and No has consolidated my respect for Larraín’s work. This release comes with some excellent contextual material and is highly recommended. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|