|

|

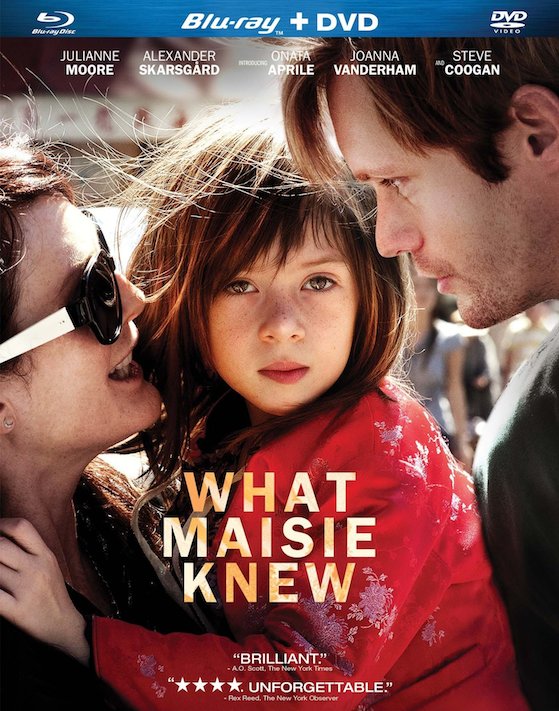

What Maisie Knew

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray A - America - Millennium Films Review written by and copyright: Ethan Stevenson (10th December 2013). |

|

The Film

American-born British author Henry James spent the better part of his first 20 years of life straddling the Atlantic. Born in New York, his parents, both well-to-do intellectuals—his father was a theologian—sent James to school in Europe; he ultimately settled in England, where he went on to write a number of acclaimed novels, most of which concerned themselves with social criticism, if not outright condemnation, of the Victorian times in which he was writing, usually through the eyes of an at-times untrustworthy narrator. One of these books, which was first published as a serial in the late 1890's, was “What Maisie Knew”, the story of a young girl born to an upper-class English couple who engage in extramarital affairs, eventually divorce, remarry different partners, and then frequently leave their daughter with their new spouses, who also engage in an affair themselves. Poor Maisie is caught in the middle of this dysfunction, often used as a pawn, more often completely forgotten. She rarely understands what the adult reader gets implicitly. To Maisie, much of what happens to her is fun; new experiences made magical by the lighthearted, innocent joys of childhood. But we know it is not; Maisie’s is a tale of heartbreaking neglect, manipulation, and tragedy. Directors Scott McGehee and David Siegel’s new film version of “Maisie” is thoroughly modern, and translates the setting from turn of the 19th century England back to James’ native New York City. Present day, post-9/11 New York City to be exact. But superficial differences in location and time aside, it’s a fantastic adaptation of James’ story; one that still has the slight cynicism of the source, once covert but now more overt, and keeps the cultural and social criticism at a constant bubble underneath the action and at times predictably contrived plot. McGehee and Siegel, working from a script by Nancy Doyne and Carroll Cartwright, update a novel with surprisingly effort to find an analog. The novel was written at a time when divorce was a scandalous rarity but becoming increasingly common (one might even say a “social problem” of the day), and the cherished concept of childhood—the new notion that those under a certain age were not just little versions of normal sized people, but complex and sometimes even chemically imbalanced proto-people—was still similarly novel. The film came to be in an era where almost the opposite is true. In 2013, one in every two marriages ends in divorce; in the westernized world, childhood is taken for granted, and its innocence thoughtlessly exploited. Yet they find the commonality; the similarity in the difference, and that very little, 120 years on, has changed. In the film, the mother and father of James’ story are made a rock star and some sort of financial finagler respectively; Julianne Moore plays Susanna, a Courtney Love-esque party parent, while Steve Coogan makes a rare turn as the straight man to his costars lunacy in Beale, a British businessman. As the film begins, Maisie’s parents are already separated—if not legally, at least logistically. The rarely see each other, and when they do, they do nothing but argue, scream, and cry. Susanna has had enough of her continent-hopping husband, who is often away in Asia or Europe brokering a deal, and finally kicks him out of their high-rise loft by changing the locks. When Beale comes back from a trip to find himself without a home, he tries to force his way in, with shouted words—“open the door, you f**king b*tch!”—and pounding fists. Susanna is on the verge of a breakdown, crying, and threatens to call the police. We witness this scene not through an omnipotent view, free flowing between shots from either side—or even one side of the door— but through the eyes of 7-year old Maisie (Onata Aprile), who’s hiding upstairs just out of sight. We hear the words, and occasionally see the action unfold from obtuse angles—peeks from out of the cover of supposed safety—in a way that’s voyeuristic, and naive. Like the reader of James’ novel, the viewer of McGehee and Siegel’s film is presumably adult, and gleans much more from the subtitles of these scenes and this innocent approach than the character, or talented young actress playing the character, does herself. Maisie often doesn’t fully comprehend what’s going on around her; when she sees her father and nanny, Margo (Joanna Vanderham), talking close—we know too close to not be romantically intimate—she thinks little of it. She is eager to please her flaky and fickle mother, who often looks at motherhood as a burden through booze-blinding glasses; to make her happy when Maisie’s very existence often seems to do the exact opposite. There is a sense of impending doom in their relationship, but it is only impending. One assumes years from now, when Maisie is older, she will realize what a terrible person her mother, and indeed both parents have been. But for now she delights in the infrequent mommy-daughter days in the recording studio, and empty gestures and the play things her mother provides, her favorite of which happens to be Susanna’s new husband, Lincoln (Alexander Skarsgård), a kindly, sort of stupid bartender with aspirations of being a sous-chef. Lincoln, like nanny Margo, is kind and treats Maisie like she needs to be—with care. Sometimes, this means coddling her; other times, it means teaching her; most times it means simply being there for her however, whenever. Whereas both Susanna and Beale are unable to even attempt to do this for whatever, usually selfish, reason, Margo and Lincoln treat her like their own, even when they are cruelly reminded that she most decidedly isn’t. McGehee and Siegel wrangle their picture with a sure hand, letting the actors freely improvise—especially Aprile, whom the directors consistently, rightfully, praise for her naturalistic performance in their commentary—but always bring scenes back into focus; bore to the core of the emotion, and delicate balance between melancholy and cheering joy. Aprile takes care of most the joy here, doing the heavy lifting in little scenes where she discovers something knew about the world, and articulates all the right facial ticks and nuances you’d expect from a trained student of theatre, not a 7 year old amateur. Because her performance is so naturalistic, at some point “Maisie” transcends the few falsities of its manufactured slice-of-life trappings and simply becomes real for the remainder of the runtime. Coogan, who bares his soul in a scene where he tells his daughter he is leaving to live in England and that he probably won’t see her again for years, and Moore—scarily, oddly, believable in a part that I initially would’ve thought she too old, and too kind, to play—and the rest just sort of become their characters. Not actors playing parts, but real people, in real, usually depressing, situations. Because, for most of its runtime, it feels not one bit false, “What Maisie Knew” is not always easy to watch. In fact, even in the brief moments of bliss, it can be quite a difficult film. On one level, this is because whenever something bad happens, it’s he result of a child being manipulated by these people who are supposed to care for her—to serve their purpose, and fulfill their wants and needs, not done in her best interest. On another, each scene is difficult because you know nothing good will come of it in the end. Even the final shot—in which Maisie is seen running down a boat dock, a smile on her face, the wind in her hair, backlit by bright sunlight—has a sense of sorrow to it. Yes, she’s happy in that moment; but the feeling will be fleeting, like childhood. It will soon come to an end, corrupted by those terrible forces around her. McGehee and Siegel’s film is excellent, and almost everything about it (save for some of the contrivance towards the end; particularly, how Susanna seemingly always just shows up at the right time to ruin anything good) is tip-top, from the performances, and the visual design, on down. But it isn’t an easy watch, although I do recommend it.

Video

“Maisie’s” 2.40:1 widescreen 1080p 24/fps AVC MPEG-4 high definition transfer is low-key, but with bursts of brilliance. For the most part, the film is unassuming, bathed in naturalistic colors, with modest contrast, decent but not extraordinary detail, a fine layer of film grain, and minimalist framing and camera movement courtesy DP Giles Nuttgens. But several sequences, such as when Maisie visits the park with Lincoln, or the beach with Margo, are buoyant, supersaturated moments of hyper-detail and abstraction. These more fantastical portions of the film have slightly overcooked contrast—resulting in some slight, blooming highlights—and a cheerful, almost dreamlike quality that runs counter to the otherwise unpretentious, modest visuals of the rest of the film. In either visual mode, the blu-ray is a fantastic transfer—gorgeous, albeit usually in an understated way. There is one issue I couldn’t quite pin down, and it’s a disconcerting one that seems out of place in an otherwise impressive presentation. At several points throughout the film, select shots have a weird stuttering, smeary, almost video-like, quality. I’m uncertain if is an authoring error, or related to the shutter speed of the camera used in each shot as an intentional stylistic effect, which I don’t discount, as each instance arrives during surrealistic scenes shot with slow-mo inserts. These few problem shots aside, “What Maisie Knew” is a more than satisfying high def presentation.

Audio

Millennium’s English Dolby TrueHD 5.1 offering is equally satisfying, and similarly low-key with sporadic sense of powerful immersion. Much of “What Maisie Knew”, or knows, she gleans from hard-heard conversations and arguments harshly and hurriedly whispered. Much of the soundtrack then is not big, bombastic, and showy, but rather reserved. Dialog, even the hushed insults hurled a room or two away, come through clean and are always, perhaps unfortunately for little Maisie, intelligible. Rear activity kicks into the soundtrack whenever scenes take place outdoors, with the hustle and bustle of New York City providing a lively atmosphere. The disc also includes an English Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo downmix, and optional subtitles in English and Spanish.

Extras

Co-directors Scott McGehee and David Siegel offer a reserved but interesting audio commentary. The two discuss the adaptation of a novel set in Victorian-era England to modern day New York City, the importance of allowing actor improvisation, directing children, and more. The track has a few some silent spots and is often resembles a calm, quiet chat, but ultimately proves worth a listen for their comments on the pictures larger themes, and similarities and differences between the societal environments in which the book and film were produced. The disc also includes four deleted scenes (2.40:1 widescreen, 1080p; 7 minutes 20 seconds, play all). In “Locksmith”, Maisie has a conversation with a locksmith; “Photo Shoot” is another self-explanatory scene, in which Maisie attends a photo shoot with her mother; Maisie’s out on the town by herself in “Run Out and Holly”; and finally, “Susanna’s Music Video” features Moore in character doing a mock-rock concert. The theatrical trailer for “What Maisie Knew” (2.40:1 widescreen, 1080p; 2 minutes 15 seconds) is hidden in the “Previews” submenu. The following bonus trailers are also found under “Previews”, and auto-play before the menu upon disc start up: - “Upside Down” (2.35:1 widescreen, 1080p; 2 minutes 31 seconds). - “Stuck in Love” (2.35:1 widescreen, 1080p; 2 minutes 23 seconds). - “The Iceman” (1.85:1 widescreen, 1080p; 2 minutes 30 seconds). - “Killing Season” (2.42:1 widescreen, 1080p; 1 minute 40 seconds).

Packaging

“What Maisie Knew” is available as either a standard single-disc Blu-ray or a 2-disc Blu-ray + DVD Combo Pack from Millennium Entertainment. The single disc release contains a Region A locked BD-25, housed in an Elite keep case. The Combo includes a DVD-9 locked to Region 1, in addition to the high def disc. First pressings of the Combo Pack include a slip-cover; the single disc is slip-less from the outset.

Overall

Equal parts morose melancholy and heart-hurting happiness, “What Maisie Knew” is a movie about a child, and childhood, made for adults. Maisie knows very little about what’s going on around her, but we know it’s tragic. There’s a good chance this film will absolutely wreck you, in part because Aprile’s naturalistic performance—and the expert work from the supporting, adult, cast—makes this slice-of-life saga a bittersweet experience that feels almost too real. Considering the somber streak that runs through the narrative, the Blu-ray release has an almost disconcertingly cheery, vibrant, video transfer, and a supportive soundtrack. An audio commentary offers some welcome insight into the adaptation, but there are few extras beyond that to be had. On the strength of the film, and presentation, “What Maisie Knew” is recommended.

|

|||||

|