|

The Film

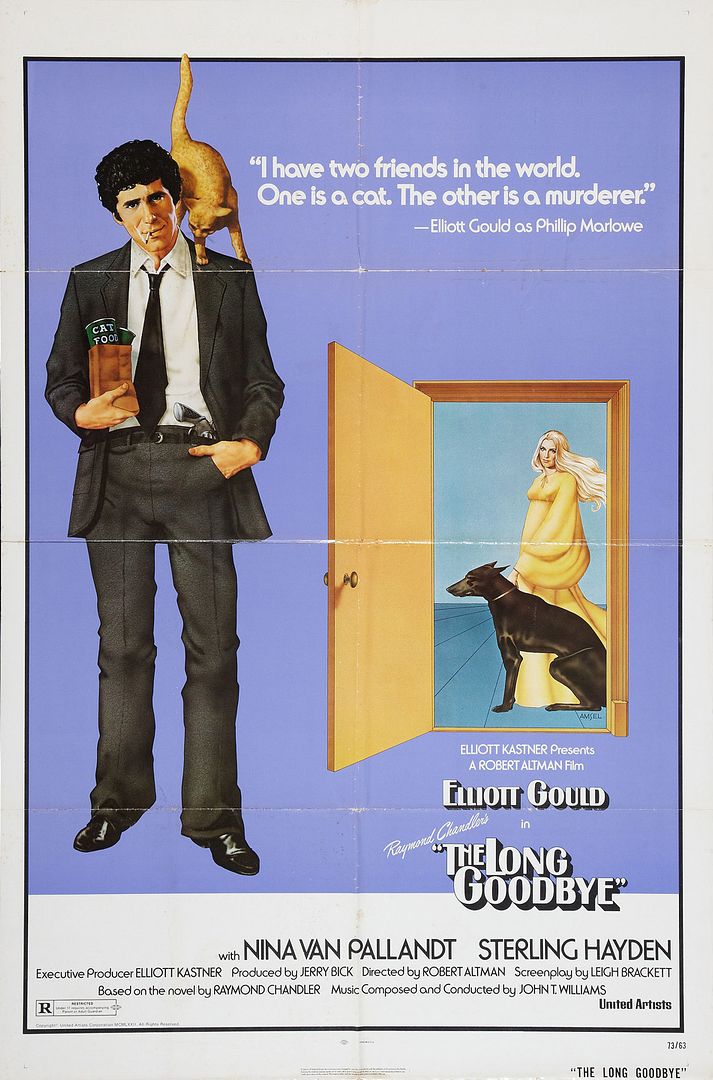

The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973)

The film rights to Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye were bought by producer Elliott Kastner on 1965. A script was completed by Stirling Silliphant in 1968; a year later, Silliphant’s adaptation of Chandler’s The Little Sister was produced under the title Marlowe, with James Garner taking on the role of Philip Marlowe. Silliphant’s script for The Long Goodbye would never reach the screen, however: in 1972, Brian G Hutton was approach to direct the film, and a new script was commissioned from Leigh Brackett. Brackett, of course, had written the script for Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1946), which to that point was one of the most highly regarded Chandler adaptations. The film rights to Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye were bought by producer Elliott Kastner on 1965. A script was completed by Stirling Silliphant in 1968; a year later, Silliphant’s adaptation of Chandler’s The Little Sister was produced under the title Marlowe, with James Garner taking on the role of Philip Marlowe. Silliphant’s script for The Long Goodbye would never reach the screen, however: in 1972, Brian G Hutton was approach to direct the film, and a new script was commissioned from Leigh Brackett. Brackett, of course, had written the script for Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1946), which to that point was one of the most highly regarded Chandler adaptations.

Brackett struggled to adapt the novel, claiming that it ‘was an enormous book’ that, if given a ‘straight’ adaptation, would have resulted in ‘a five-hour film’ (Brackett, quoted in Phillips, 2003: 147). Where The Big Sleep was ‘brisk, a swift succession of scenes’, Chandler’s The Long Goodbye developed two parallel narratives: the story of Terry Lennox, Marlowe’s friend who enlists Marlowe’s help in absconding to Tijuana following the murder of his wife, and the parallel story of Eileen Wade and her husband Roger, a writer with a drinking problem whose publisher, Howard Spencer, enlists Marlowe to keep an eye on him. Brackett argued that the story was brought to a halt by ‘the complicated progression of the overlapping stories’ (Brackett, quoted in ibid.). She suggested that although this narrative structure worked for the novel, it would not translate so well to film, and consequently she removed a number of ancillary characters from the plot. So in Brackett’s screenplay, it isn’t Wade’s publisher who hires Marlowe: Marlowe is approached instead by Eileen Wade, who sees Marlowe’s name in the newspaper following the scandal surrounding the murder of Sylvia Lennox. Brackett also removed the characters of Sylvia Lennox, who in the completed film is never seen onscreen, and her sister Linda. Additionally, Brackett changed the resolution of the narrative significantly, leading to Marlowe committing an act that many Chandler purists found deeply problematic.

Altman removed two sequences that Brackett included in her screenplay: a scene in which Wade discusses suicide with Marlowe, which clarifies Wade’s motives for his suicide later in the film (Brackett’s screenplay makes it clear that Wade commits suicide owing to his failure as a writer); and a sequence in which Terry tells Eileen to return the stolen money to Marty Augustine, which reveals that Eileen has been in contact with Terry all along. Brackett was reputedly quite upset with Altman’s decision to remove both sequences: she felt that they clarified several plot points (see Phillips, op cit.: 150). However, the scenes are arguably unnecessary: an astute and active viewer will most likely arrive at the same interpretations of the characters’ actions without the aid of either of these sequences.

There was negative reaction to the film owing to the casting of Gould as Marlowe and the updating of the narrative to 1970s Southern California. An early prerelease screening, shown at a conference in which the five other major Chandler adaptations had already been screened, provoked largely negative responses, many of which singled out Gould’s performance as Marlowe for criticism (Phillips, op cit.: 158). By casting Gould as his ‘modern’ Marlowe, and by using a script from Brackett, Michael Wilmington suggests that Altman ‘was both making a statement on the genre and how that genre collides with the reality of the time’ (1991: 133).

Robin Wood has noted that an Altman protagonist typically has, ‘whatever his age, an adolescent quality, a combination of arrogance and vulnerability’ (2003: np). During production, Altman reputedly referred to Marlowe as ‘Rip Van Marlowe’, suggesting his conception of the character was as a man who had been asleep for almost thirty years and had awoken in a society in which his values and attitudes seemed ridiculously outmoded: Luhr notes that ‘Altman’s Marlowe feels that he lives according to superior values of the past but the movie gives no indication that those values were any better even then. Like the gateman who constantly does star imitations from old movies, Marlowe is playing largely, and irrelevantly, to himself’ (Luhr, 2012: 156). However, writing at the time of the film’s original release Judith Crist argued that Altman’s conception of Marlowe had much in common with Chandler’s perception of the character: Crist reminds us that ‘Chandler saw his tough but idealistic and decent and ethical private eye as the figment of a romantic imagination, knowing with a realist’s acceptance that it takes dirty men to thrive in a dirty business’ (1973: 80). Crist suggests that Altman’s Marlowe is ‘half in sorrow and half in laughter, as a man out of his time’: he clings ‘not only to the clothes, the unfiltered cigarettes, and even the car (a 1948 Continental convertible) but also, more importantly, to the ethic and morality of a time gone by’ (ibid.).

Robert Kolker notes that contemporary criticisms of Gould’s Marlowe frequently highlighted ‘how weak, fooled, and finally violent Altman’s Marlowe is’, especially in comparison with Humphrey Bogart’s depiction of Marlowe in Hawks’ The Big Sleep – still for many the definitive screen representation of Chandler’s iconic character. Kolker suggests that Bogart’s Marlowe was depicted as being in control within a ‘closed, dark, and, in its corruption, curiously stable world’; this control was exercised only through Marlowe’s ‘wit and his ability to find momentary attachments based on the least amount of mistrust’ (2011: 390). Despite this, in the narrative of The Big Sleep Marlowe becomes ‘deeply entangled’ in the world he enters, ‘played for a fool by everyone and […] reduced to committing murder as vicious as any committed by the various thugs, grifters, blackmailers, and rich young women who drift in and out of the film’s complex narrative’ (ibid.). Robert Kolker notes that contemporary criticisms of Gould’s Marlowe frequently highlighted ‘how weak, fooled, and finally violent Altman’s Marlowe is’, especially in comparison with Humphrey Bogart’s depiction of Marlowe in Hawks’ The Big Sleep – still for many the definitive screen representation of Chandler’s iconic character. Kolker suggests that Bogart’s Marlowe was depicted as being in control within a ‘closed, dark, and, in its corruption, curiously stable world’; this control was exercised only through Marlowe’s ‘wit and his ability to find momentary attachments based on the least amount of mistrust’ (2011: 390). Despite this, in the narrative of The Big Sleep Marlowe becomes ‘deeply entangled’ in the world he enters, ‘played for a fool by everyone and […] reduced to committing murder as vicious as any committed by the various thugs, grifters, blackmailers, and rich young women who drift in and out of the film’s complex narrative’ (ibid.).

By contrast, in Altman’s The Long Goodbye ‘that control’ exercised by Bogart’s Marlowe is shown ‘to be tenuous at best, fraudulent at worst’ (ibid.). Brackett and Altman ‘strip away the security of the Bogart persona, his wit and his ability to stand back from a given situation in a posture of self-preservation’ (ibid.). He is anchored to the world only by his relationship with his cat, who shortly after the opening sequence disappears. He struggles to communicate with those around him: his ‘every connection with the world is faulty and noncomprehending’ (ibid.: 390-1). His exchanges with other characters are frequently predicated on misunderstandings and mumbled asides, either misheard or unheard by the people with whom Marlowe is conversing. Kolker highlights the conversation Marlowe has with his young, stoned female neighbours following the disappearance of his cat. ‘I didn’t know you had a cat’, one of the women says when Marlowe asks if she has seen his pet. ‘Say you wanted a hat?’, another of the women asks. ‘No, no. You don’t look fat’, Marlowe responds. As Kolker observes, ‘the verbal language drifts and glances in incoherent directions’ and the camera ‘drifts and pans, zooms slowly in and out (never completing its motion), arcs and dollies until the viewer’s own perceptions are inscribed into an orderless, almost random series of interchanges and events’ (ibid.: 391).

Even Marlowe’s attempts at wit are continuously misunderstood or, more frequently, ignored. Marlowe’s repeated line, ‘It’s okay with me’, typically delivered after Marlowe is exposed to behaviour that may be seen as unusual or deviant, is mumbled and signifies his passivity: it is all that ‘has become of the Marlowe persistence and drive for moral order. And in his insular state Marlowe merely allows himself to be had’ (ibid.). Parallels may be drawn between Marlowe’s repeated line and the lyrics of the song of the final song in Altman’s Nashville (1975) (‘You may say that I ain’t free / But it don’t worry me’): as Jane Feuer notes, in that film ‘[s]inging becomes a way of lulling an audience into a celebration of its own complacency’ (1976: 31). Marlowe’s decision to prove that his friend Terry Lennox is innocent of the murder of his wife is ultimately revealed to be irrational and wrongheaded, reminding us that a frequent theme in Altman’s work is the relationships between friendship and betrayal (Kolker, op cit.: 391). For William Luhr, ‘Brackett’s Marlowe is not a hero and is not taken seriously by other characters; he is simply a patsy’ (2012: 159). However, although Marlowe may be ‘hollow and deluded […] no one else comes off any better’ (ibid.: 166). All of the film’s characters are, in some way, depicted as ‘manipulative, self-deluded, or evil’ (ibid.). The film ‘depicts a world without a moral center, something which the Marlowe of earlier movies often provided. The Long Goodbye shows us a world going nowhere, like its vision of the revival of film noir’ (ibid.).

The laconic, insular character of Marlowe is within a spectrum of stereotypical male behaviour that Altman’s film interrogates in a very direct manner. Wilmington suggests that the film offers a critique of macho cultures, from the laconic Marlowe to the hard-living, heavy-drinking Wade - ‘who’s kind of Hemingwayesque, too’ - and the misogynistic Marty Augustine - ‘who’s completely off the wall’ (Wilmington, op cit.: 135). Wade, played in larger-than-life fashion by Sterling Hayden (in a role originally intended for Dan Blocker, who sadly passed away shortly before production began), is a writer, clearly modeled on the Hemingway type, whose macho swagger is undercut as the narrative progresses. Marlowe, who has been hired by Eileen Wade to find her husband, ‘rescues’ Wade from a shady ‘drying out’ clinic that is operated by Dr Verringer (Henry Gibson): Verringer insists that Wade owes him $4,400, but Marlowe persuades Verringer to allow Wade to walk away from the clinic without paying his bill. (‘It’s not the people that are sick; it’s this place’, Wade tells Verringer.) Later, Marlowe and Wade bond over alcohol. ‘You know what I wish you’d do?’, Wade asks Marlowe, ‘I wish you’d take that J C Penney tie off and settle down with me, and you and me are going to have a good old-fashioned man-to-man drinking party’. ‘That’s okay with me, but I’m not going to take my tie off’, Marlowe responds before surprising Wade with his knowledge of the Scandinavian spirit Akvavit. Wade, it is revealed, suffers from both writer’s block and, Eileen informs Marlowe, impotence. (Wade seems to consider both to be equally shameful; both are an affront to his manhood.) Furthermore, Marlowe initially assumes that Wade has been conducting an affair with Sylvia Lennox, but it is gradually revealed that Wade has been cuckolded by his wife. The laconic, insular character of Marlowe is within a spectrum of stereotypical male behaviour that Altman’s film interrogates in a very direct manner. Wilmington suggests that the film offers a critique of macho cultures, from the laconic Marlowe to the hard-living, heavy-drinking Wade - ‘who’s kind of Hemingwayesque, too’ - and the misogynistic Marty Augustine - ‘who’s completely off the wall’ (Wilmington, op cit.: 135). Wade, played in larger-than-life fashion by Sterling Hayden (in a role originally intended for Dan Blocker, who sadly passed away shortly before production began), is a writer, clearly modeled on the Hemingway type, whose macho swagger is undercut as the narrative progresses. Marlowe, who has been hired by Eileen Wade to find her husband, ‘rescues’ Wade from a shady ‘drying out’ clinic that is operated by Dr Verringer (Henry Gibson): Verringer insists that Wade owes him $4,400, but Marlowe persuades Verringer to allow Wade to walk away from the clinic without paying his bill. (‘It’s not the people that are sick; it’s this place’, Wade tells Verringer.) Later, Marlowe and Wade bond over alcohol. ‘You know what I wish you’d do?’, Wade asks Marlowe, ‘I wish you’d take that J C Penney tie off and settle down with me, and you and me are going to have a good old-fashioned man-to-man drinking party’. ‘That’s okay with me, but I’m not going to take my tie off’, Marlowe responds before surprising Wade with his knowledge of the Scandinavian spirit Akvavit. Wade, it is revealed, suffers from both writer’s block and, Eileen informs Marlowe, impotence. (Wade seems to consider both to be equally shameful; both are an affront to his manhood.) Furthermore, Marlowe initially assumes that Wade has been conducting an affair with Sylvia Lennox, but it is gradually revealed that Wade has been cuckolded by his wife.

Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) is another extreme of male behaviour; Augustine is at the centre of the film’s most shocking sequence. The character is first introduced outside Marlowe’s apartment. Convinced that Marlowe knows the whereabouts of the $355,000 of mob money that Terry Lennox apparently used to aid his flight from the law, Augustine quizzes Marlowe; Marlowe responds to Augustine’s threats with his typically nonchalant quips. ‘I only see hoods by appointment’, Marlowe says before he is beaten and dragged into his apartment where, as Augustine’s gang enter the room, he reflects on the diverse ethnic makeup of the group: ‘I see you got a Mexican, an Irish guy, a Jewish fella and an Italian-American’. Augustine taunts Marlowe, ordering him to punch him in the stomach, and he attempts to mock Marlowe by boasting of his importance (in a monologue that resonates with James Franco’s similar ‘Look at all my sheeyit’ outburst in Harmony Korine’s recent Spring Breakers, 2013): ‘I got chauffeurs, I got maids, I got butlers, I got cooks. I live highly. It costs me a lot of money to live where I live. I gotta have a lot of money so I can juice the guys I gotta juice, so I can get a lotta money so I can juice the guys I gotta juice. And you, Cheapie, you can’t take my money. I want my money’. Augustine’s rant is interrupted by his mistress, Jo Ann Eggenweiler (Jo Ann Brody). Augustine praises the beauty of Jo Ann, ‘the single most important person in my life, next to my family’, before unexpectedly smashing a glass Coca-Cola bottle in her face. ‘Now, that’s someone I love. You, I don’t even like’, Augustine threatens Marlowe before commanding him to ‘find my money’. This sequence was added at a relatively late stage during the production; Altman has said that the scene was intended to introduced ‘violence into the film’, reminding the audience that ‘in spite of Marlowe, there is a real world out there; and it is a violent world’ (Altman, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 154).

The sequence has strong similarities with the scene in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) in which Lee Marvin’s hood, fired up by sexual jealousy, unexpectedly throws a pot of scalding coffee in the face of Gloria Grahame’s moll. Both sequences feature abrupt, senseless violence directed against quiet, beautiful women who are the ‘hangers on’ of gangsters. Peter Lehman has connected the scene in Lang’s film to the sequence in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) in which one of Mark Lewis’ (Carl Boehm) photographic models is seen only in profile until she turns her head towards the camera, revealing that ‘the other side of her face is horribly disfigured’ (2007: 68). Lehman suggests that such sequences suggest that to ‘disfigure the woman, whose power comes from her beauty, is to mark her loss of power’ (ibid.) As Lehman argues, ‘when women’s faces are damaged in films, the mark is frequently confined to one side only’ (ibid.): in The Long Goodbye, Jo Ann is in later sequences shown to still be in association with Augustine, her face partially covered by a bandage, this partial covering ensuring juxtaposition of her still-evident beauty and the bandage which signifies Augustine’s cruelty. Such iconography, Lehman argues, ‘makes clear the structure that underlies this scarring of the woman’s face: the shocking contrast between beauty and its loss is heightened’ (ibid.).

The contrast between high ideals and harsh reality is also underlined by the film’s use of the song ‘Hooray for Hollywood’, from the 1937 Busby Berkeley musical Hollywood Hotel - which incidentally starred Dick Powell, the actor who portrayed Marlowe in Murder My Sweet (Edward Dmyryk, 1944). ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ opens and closes Altman’s The Long Goodbye, playing under the United Artists logo that opens the film and over the closing shot of Marlowe walking along a tree-lined avenue, along the way passing Eileen Ward, who is headed in the opposite direction. (The latter is a shot that, many commentators have noted, seems to be a direct allusion to the closing shot of Carol Reed’s classic 1948 film noir The Third Man.) Daniel O’Brien has noted that all of the film’s ‘references to the movie industry—present throughout the film but fairly peripheral—look back to the Golden Age’ (O’Brien, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 155). Aside from the visual allusion to The Third Man and Altman’s borrowing of ‘Hooray for Hollywood’, there is of course the security guard (Ken Samson) of the Malibu Colony where both the Lennoxes and Wards live, who performs impersonations of classical Hollywood stars: he is introduced in the opening sequence, where he impersonates Barbara Stanwyck from Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) for Terry Lennox as he leaves the Colony. (The guard’s ‘performance’ as Stanwyck’s character from the Wilder film is ironic inasmuch as Lennox is fleeing from the Malibu Colony having just murdered his wife.) Later, the guard impersonates Jimmy Stewart and Cary Grant, and Marlowe exploits the guard’s peculiar skill to delay Harry (David Arkin), one of Augustine’s hoods who is following Marlowe, telling the guard that Harry is a ‘very big fan of Walter Brennan’. The contrast between high ideals and harsh reality is also underlined by the film’s use of the song ‘Hooray for Hollywood’, from the 1937 Busby Berkeley musical Hollywood Hotel - which incidentally starred Dick Powell, the actor who portrayed Marlowe in Murder My Sweet (Edward Dmyryk, 1944). ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ opens and closes Altman’s The Long Goodbye, playing under the United Artists logo that opens the film and over the closing shot of Marlowe walking along a tree-lined avenue, along the way passing Eileen Ward, who is headed in the opposite direction. (The latter is a shot that, many commentators have noted, seems to be a direct allusion to the closing shot of Carol Reed’s classic 1948 film noir The Third Man.) Daniel O’Brien has noted that all of the film’s ‘references to the movie industry—present throughout the film but fairly peripheral—look back to the Golden Age’ (O’Brien, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 155). Aside from the visual allusion to The Third Man and Altman’s borrowing of ‘Hooray for Hollywood’, there is of course the security guard (Ken Samson) of the Malibu Colony where both the Lennoxes and Wards live, who performs impersonations of classical Hollywood stars: he is introduced in the opening sequence, where he impersonates Barbara Stanwyck from Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) for Terry Lennox as he leaves the Colony. (The guard’s ‘performance’ as Stanwyck’s character from the Wilder film is ironic inasmuch as Lennox is fleeing from the Malibu Colony having just murdered his wife.) Later, the guard impersonates Jimmy Stewart and Cary Grant, and Marlowe exploits the guard’s peculiar skill to delay Harry (David Arkin), one of Augustine’s hoods who is following Marlowe, telling the guard that Harry is a ‘very big fan of Walter Brennan’.

‘Hooray for Hollywood’ (and the closing pastiche of the final shot of The Third Man) references Hollywood’s past ironically. As William Luhr notes, like the iconography that surrounds Marlowe (the 1948 Lincoln Convertible, his dress, the constant smoking, and even his ironic appropriation of blackface when he is arrested by the police), the song is strongly marked as a product of a bygone era: ‘The outdated quality of the recording is marked by the performance style of the vocalists, the orchestration, and its poor, scratchy, audio quality. These things categorize it, like the Hollywood it celebrates, as an artifact from a past era’ (Luhr, op cit.: 162). Daniel O’Brien has suggested that in this context, Altman’s use of ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ is ironic, reminding us that ‘[t]here is nothing to cheer about in the Hollywood Altman has just shown us. All references to the movie industry—present throughout the film but fairly peripheral—look back to the Golden Age’ (O’Brien, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 155). For Robert T Self, Altman’s use of this song reminds us that Altman is ‘revis[ing] the Hollywood detective hero for the antiheroic mood of the American public at the end of the Vietnam War’ (2002: 182). ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ (and the closing pastiche of the final shot of The Third Man) references Hollywood’s past ironically. As William Luhr notes, like the iconography that surrounds Marlowe (the 1948 Lincoln Convertible, his dress, the constant smoking, and even his ironic appropriation of blackface when he is arrested by the police), the song is strongly marked as a product of a bygone era: ‘The outdated quality of the recording is marked by the performance style of the vocalists, the orchestration, and its poor, scratchy, audio quality. These things categorize it, like the Hollywood it celebrates, as an artifact from a past era’ (Luhr, op cit.: 162). Daniel O’Brien has suggested that in this context, Altman’s use of ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ is ironic, reminding us that ‘[t]here is nothing to cheer about in the Hollywood Altman has just shown us. All references to the movie industry—present throughout the film but fairly peripheral—look back to the Golden Age’ (O’Brien, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 155). For Robert T Self, Altman’s use of this song reminds us that Altman is ‘revis[ing] the Hollywood detective hero for the antiheroic mood of the American public at the end of the Vietnam War’ (2002: 182).

Video

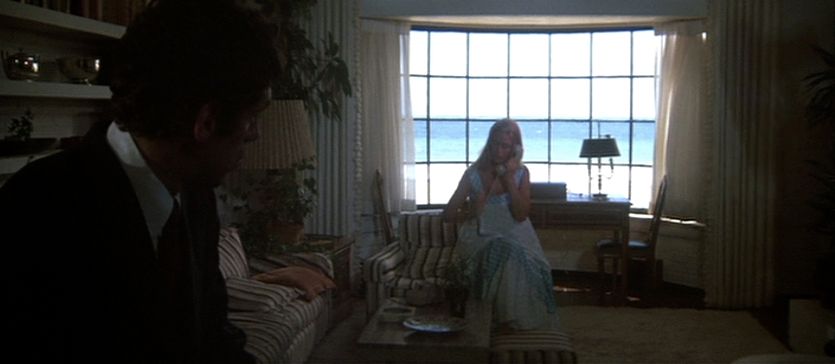

Michael Wilmington suggests that the ‘major visual innovation’ that Altman introduced to his work with The Long Goodbye was ‘a floating kind of camera work’ (op cit.: 132). William Luhr notes that, in conflict with the conventions of traditional Hollywood filmmaking, in The Long Goodbye Altman and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond avoid providing a clear focal point in each shot: the camera ‘seems constantly to be roving through the sets and among the characters in what at times seems an arbitrary manner’ (op cit.: 162). Luhr suggests that this is an attempt to ‘reinvent […] the destabilization and visual disorientation of film noir by employing new strategies to produce comparable effects within the audience’ (ibid.). For example, in the sequence in which Wade commits suicide, Altman and Zsigmond continually destabilise the audience’s interpretation of what is taking place onscreen. Eileen Wade asks Marlowe to stay with her, preparing a candlelit meal. Following the meal, Marlowe and Eileen Wade stand in front of a window of the Wade house that overlooks the beach. The camera dollies towards the pair, signifying an increased intimacy; but as Marlowe breaks the potentially romantic mood by asking Eileen about her husband’s relationship with Augustine, the camera slowly zooms past them to reveal, in long shot, Roger Wade staggering in to the surf. Luhr notes that this is ‘a remarkable scene that repeatedly changes its meaning, all in one, slowly moving shot [….] At first, the shot seems to be “about” a romantic situation, then “about” the abrupt breaking of that mood to refocus on the facts of the case, and finally “about” the discovery and shock of Roger Wade’s suicide’ (ibid.: 165). For Luhr, this shot ‘encapsulates the movie’s pervasive atmosphere of instability and unexpected discoveries’ (ibid.).

Zsigmond has described this constantly moving camera as a ‘visual experiment’, stating that he and Altman ‘decided that we were going to move the camera every single frame of the picture to create the nonexistent third dimension’ (Zsigmond, quoted in Schaefer & Salvato, 1985: 335). Suggesting that as with painting, photography communicates the ‘third dimension’ through lighting, Zsigmond argues that in shots created with a mobile camera (such as dolly shots and crane shots), an image is provided with the illusion of three dimensions ‘because suddenly you see the foreground, background and middleground moving against each other’ (ibid.: 335-6). Consequently, to achieve this within The Long Goodbye, Zsigmond concluded that every shot, ‘even if it was a close-up’, must ‘be a moving shot’: ‘We just kept the camera moving right or left or we zoomed in and out’ (ibid.: 336). Zsigmond has described this constantly moving camera as a ‘visual experiment’, stating that he and Altman ‘decided that we were going to move the camera every single frame of the picture to create the nonexistent third dimension’ (Zsigmond, quoted in Schaefer & Salvato, 1985: 335). Suggesting that as with painting, photography communicates the ‘third dimension’ through lighting, Zsigmond argues that in shots created with a mobile camera (such as dolly shots and crane shots), an image is provided with the illusion of three dimensions ‘because suddenly you see the foreground, background and middleground moving against each other’ (ibid.: 335-6). Consequently, to achieve this within The Long Goodbye, Zsigmond concluded that every shot, ‘even if it was a close-up’, must ‘be a moving shot’: ‘We just kept the camera moving right or left or we zoomed in and out’ (ibid.: 336).

In addition to this use of a roving camera, Altman and Zsigmond created an unusual ‘look’ for the film by ‘flashing’ the negative, thus ‘degrad[ing] the contrast’ (ibid.). (This is a process Altman and Zsigmond also used on McCabe and Mrs Miller, 1971.) ‘Flashing’ involves exposing the negative to light prior to developing it, and has the effect of reducing both colour intensity and contrast: flashing a positive print will soften the highlights whilst retaining the blacks; flashing a negative, as Altman and Zsigmond did, will principally soften the blacks. Zsigmond asserted that with the film, he and Altman ‘did not want to recreate the fifties but to remember them’: the muted pastel colours created by flashing the negative signified memory and reflection (‘Pastels are for memory’), whilst the ‘blue shading in night effects also will give a feeling of the fifties’ (Zsigmond, quoted in Conteris, 1999: 91). Altman has stated that the flashing process ‘cuts the contrast down and it fogs the film, actually. We did it in order to get this kind of glare that I wanted from Los Angeles in this. It was ignorant, I later decided. And we fogged this film [The Long Goodbye] 100 percent, and we shot all of it that way. And I’m sure it also helps the deterioration of the negative. I think we advanced it about ten years ourselves’ (Altman, quoted in Wilmington, op cit.: 144). In later years, Altman reflected that this process was ‘a big risk’ but was the only way this aesthetic could be achieved, and ‘by doing it on the negative, the studio would have no choice but to accept it’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, 2011: np). For the application of these innovative techniques, the National Society of Film Critics named Zsigmond as the best cinematographer of 1973 for his work on this film.

The 1080p presentation (using AVC/MPEG-4 compression) on this Blu-ray release from Arrow is faithful to the low contrast, desaturated and diffused appearance of the film. It is a filmlike presentation, with strong detail and the natural grain structure of 35mm film. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Linear PCM mono track. This is clear throughout. The disc also includes English (HoH) subtitles.

Extras

The disc contains an excellent array of contextual material, including the ‘Rip Van Marlowe’ featurette that was contained on MGM’s DVD release of the film from the early 2000s (24:35).

In addition to this, the disc includes ‘Robert Altman: Giggle and Give In’, the excellent Altman-focused episode of the BBC series Cinefile from 1996 (56:32). This documentary covers Altman’s career up to the mid-1990s.

The disc also contains a broad range of interviews: ‘Elliot Gould discusses The Long Goodbye’ features Gould in conversation with crime novelist Michael Connolly (53:05); ‘Vilmos Zsigmond Flashes The Long Goodbye’ features the cinematographer talking about his work on the picture (14:23); ‘David Thompson on Robert Altman’ features film historian/critic Thompson talking generally about Altman’s career (21:04); in ‘Tom Williams on Raymond Chandler’s Work’, Chandler’s biographer discusses the work of the iconic novelist (14:29); and ‘Maxim Jakubowski on Hard Boiled Fiction’ offers a précis of the history of hardboiled crime fiction in the Twentieth Century (14:33).

An isolated music and effects track (in mono) is also included on the disc.

Finally, the disc includes the film’s original theatrical trailer and several radio spots (2:34).

Overall

Altman and Brackett’s unconventional adaptation of Chandler’s novel was greeted with derision on its initial release owing to perceptions that it was disrespectful to the source novel. However, with hindsight it may be suggested that this is a very honest interpretation of the book and its relationship with then-contemporary society: the criticisms of the film seem to focus on the differences between Gould’s Marlowe and the Marlowe played by Humphrey Bogart, but as noted above there are more similarities between the two depictions of Chandler’s character than there may at first glance appear to be. Interestingly, Marlowe’s going rate in Altman’s The Long Goodbye ($50, plus expenses) is exactly half what the character charged in Marlowe. When John Houseman asked Chandler why Marlowe charges so little for his services in the novels, Chandler told Houseman that ‘it is tough to be both honest and financially successful in a rotten world’ (Chandler, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 148). Altman and Brackett’s unconventional adaptation of Chandler’s novel was greeted with derision on its initial release owing to perceptions that it was disrespectful to the source novel. However, with hindsight it may be suggested that this is a very honest interpretation of the book and its relationship with then-contemporary society: the criticisms of the film seem to focus on the differences between Gould’s Marlowe and the Marlowe played by Humphrey Bogart, but as noted above there are more similarities between the two depictions of Chandler’s character than there may at first glance appear to be. Interestingly, Marlowe’s going rate in Altman’s The Long Goodbye ($50, plus expenses) is exactly half what the character charged in Marlowe. When John Houseman asked Chandler why Marlowe charges so little for his services in the novels, Chandler told Houseman that ‘it is tough to be both honest and financially successful in a rotten world’ (Chandler, quoted in Phillips, op cit.: 148).

Robin Wood has compared The Long Goodbye with Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975): both pictures reference classic films noirs and in both films, ‘Altman and Penn leave areas of unresolved doubt as to the various degrees of guilt and the precise motivation of certain of their characters’ (2003: np). For example, Wood admits ‘after repeated viewings I am still uncertain as to the precise nature of Eileen Wade’s involvement in the intrigue and the extent of her culpability’ (op cit: np). Altman commented that Chandler’s novel is ‘impossible to comprehend’ but that instead of becoming obsessed with the novel’s plotting, he ‘became fascinated with the way in which Chandler used the plots in stories not for story’s sake but to hang a bunch of thumbnail essays about this city, this time’ (Altman, quoted in Wilmington, op cit.: 135). Relocating the narrative from the 1940s to the 1970s allowed Altman to investigate some of these themes.

One of the key characteristics of Altman’s film, aside from some of the innovations devised by Altman and his cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (discussed above), is Altman’s use of rapid-fire, overlapping speech, which encourages the viewer to become active in their engagement with the film. Altman has claimed that his use of overlapping dialogue had a precedent in the work of Howard Hawks (Wilmington, op cit.: 140). His rationale for the use of overlapping speech is that ‘movies come from theater and theater is based on words […. s]o the structure of the words is very important’; and ‘in our lives we don’t hear everything. We hear what we want to [….] We hear a smattering of a conversation, and we kind of get it, and that really all we need’ (Altman, quoted in ibid.). Using language in such a way encourages the audience ‘to work to help make the story by the way they perceive it’, encouraging the viewer to become ‘a participant. You come and meet the screen halfway’ (Altman, quoted in ibid.).

The necessity for viewers to actively engage with the film may in part explain the negative response that greeted its initial release. Michael Wilmington asserts that ‘[t]here are lots of levels in The Long Goodbye; there are lots of ways to appreciate it. And it is a film that, to a certain degree, you have to work to get into. Maybe that is why it was not as appreciated in its time as it should have been, but why its reputation has held up’ (op cit.: 133). This Blu-ray release, containing a wonderful presentation and a fantastic spread of contextual material, will hopefully contribute to the film’s reputation.

References:

Conteris, Hiber: ‘Hiber Conteris on Raymond Chandler’. In: Stevens, Ilian, 1999: Mutual Impressions: Writers from the Americas Reading One Another. Duke University Press: 87-106

Crist, Judith, 1973: ‘Current Shock’. New York (29 October, 1973): 80

Feuer, 1976: ‘Nashville: Altman’s Open Surface’. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media (Nos. 10-11): 31-32

Kolker, Robert, 2011: A Cinema of Loneliness. Oxford University Press (Revised Edition)

Lehman, Peter, 2007: Running Scared: Masculinity and the Representation of the Male Body. Wayne State University Press

Luhr, William, 2012: Film Noir. London: John Wiley & Sons

Phillips, Gene D, 2003: Creatures of Darkness: Raymond Chandler, Detective Fiction, and Film Noir. University Press of Kentucky

Schaefer, Dennis & Salvato, Larry, 1985: Masters of Light: Conversations with Contemporary Cinematographers. University of California Press

Self, Robert T, 2002: Robert Altman’s Subliminal Reality. University of Minnesota Press

Thompson, David, 2011: Altman on Altman

Wilmington, Michael, 1991: ‘Robert Altman and The Long Goodbye. In: Sterritt, David (ed), 2000: Robert Altman: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 131

Wood, Robin, 2003: Hollywood from Vietnam to Regan … and Beyond. Columbia University Press (Revised Edition)

| The Film: |

Video: |

Audio: |

Extras: |

Overall: |

|