|

|

Spys AKA S*P*Y*S

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th July 2014). |

|

The Film

Spys (Irvin Kershner, 1974)  Produced in an attempt to rekindle some of the screen magic that had been conjured up by the pairing of Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould in Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970), Spys (Irvin Kershner, 1974) offers a satirical look at espionage during the Cold War era. As such, the film invites comparison with earlier satirical takes on the espionage thriller such as Ralph Thomas’ Bond parody Hot Enough for June (1965) and Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966); in its cartoonish mayhem and its pairing of two comic actors the film finds lineage with Morecambe and Wise’s The Intelligence Men (Robert Asher, 1965) whilst also looking forwards to freewheeling, scatalogical 1980s espionage-based comedies such as the Chevy Chase-Dan Aykroyd ‘buddy’ picture Spies Like Us (John Landis, 1985). Produced in an attempt to rekindle some of the screen magic that had been conjured up by the pairing of Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould in Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970), Spys (Irvin Kershner, 1974) offers a satirical look at espionage during the Cold War era. As such, the film invites comparison with earlier satirical takes on the espionage thriller such as Ralph Thomas’ Bond parody Hot Enough for June (1965) and Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966); in its cartoonish mayhem and its pairing of two comic actors the film finds lineage with Morecambe and Wise’s The Intelligence Men (Robert Asher, 1965) whilst also looking forwards to freewheeling, scatalogical 1980s espionage-based comedies such as the Chevy Chase-Dan Aykroyd ‘buddy’ picture Spies Like Us (John Landis, 1985).

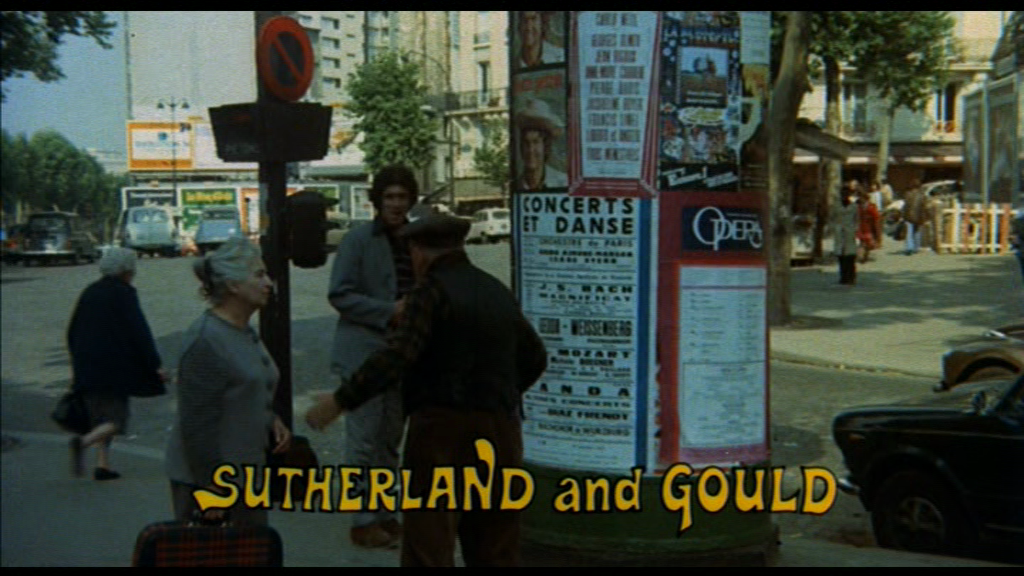

This was the last film in which Gould and Sutherland shared the screen: aside from Altman’s M*A*S*H, they had also worked together on Alan Arkin’s Little Murders (1971). The partnership between the two actors is foregrounded by the picture and its promotional material: the opening titles declare simply, ‘Sutherland and Gould’. The title of this film was sometimes written on the picture’s promotional material and posters as ‘S*P*Y*S’, in an attempt to highlight the connection with Altman’s film (which exists only in the casting of Sutherland and Gould), but in the film’s opening credits the title is written simply as ‘Spys’. Terence Pettigrew has suggested that despite the attempt to rekindle the magic of Sutherland and Gould’s work together in Altman’s M*A*S*H, ‘it was clearly a mistake to package the second film [Spys] in a way that invited such direct comparison’ with the Altman picture: despite the anarchic oddball/screwball humour and the countercultural anti-authoritarian subtext within both films, the two pictures ‘were wholly dissimilar’ in terms of ‘their pace and style, and even the characters portrayed’ by Sutherland and Gould (1982: 72). Sutherland and Gould play, respectively, Bruland and Griff, two bumbling CIA agents who first meet when they attend a ‘dead drop’ in a public lavatory in Paris. Gould is first on the scene, and reaches above the lavatory but doesn’t find the package he’s looking for; next, Sutherland arrives on a motorcycle and, fumbling for the package, accidentally detonates a bomb which destroys the public convenience. (‘I was supposed to go the pissoir to make a pickup’, Gould later asserts.) They initially believe one another to be enemy agents. Returning to their shared handler Martinson (Joss Ackland), whose office is concealed within the rear wall of a bathroom, Sutherland asserts that the bomb in the pissoir ‘was definitely KGB’, noting that Gould, who he believes to have planted the bomb, ‘had a demented Russian look’. Sutherland gets a shock when Gould enters the room and reveals himself to be not only a fellow CIA agent, but also assigned to the same handler, Martinson. Gould deduces that the bomb was placed by their own side: ‘The Chinese are quiet, right; the Russians are quick, and we are just sloppy. That [the bomb in the pissoir] was a sloppy job’. Martinson reveals that the bomb was planted as a means of getting rid of two double-agents, but owing to a clerical error Gould and Sutherland were accidentally sent to the sabotaged dead drop spot.  Martinson sends Sutherland and Gould on a mission to bring in from the cold a Soviet athlete, Sevitsky (Michael Petrovitch), who is planning to defect to the West. The scenario seems heavily based on the defection of the Russian ballet dancer/choreographer Rudolf Nureyev in 1961, which also formed the basis for Ray Cooney’s stage farce Not Now Comrade (the film version of which was released in 1976). Visiting the gymnasium whilst disguised as a photographer and journalist, Sutherland and Gould speak with Sevitsky, who claims he will only defect if he is offered a suede jacket, pants and Raquel Welch. Two MI5 agents offer Sevitsky a Triumph sports car, and the illicit negotiations break down when Sevitsky’s KGB guards spot Sutherland, Gould and the rival MI5 agents. One of the MI5 agents shoots at the KGB guards using a gun disguised as a camera. ‘These guys are crazy. Why don’t they have guns?’, Sutherland observes. ‘Why doesn’t your camera have bullets?’, Gould asks him. ‘Are you crazy? It doesn’t even have film’, Sutherland responds. Martinson sends Sutherland and Gould on a mission to bring in from the cold a Soviet athlete, Sevitsky (Michael Petrovitch), who is planning to defect to the West. The scenario seems heavily based on the defection of the Russian ballet dancer/choreographer Rudolf Nureyev in 1961, which also formed the basis for Ray Cooney’s stage farce Not Now Comrade (the film version of which was released in 1976). Visiting the gymnasium whilst disguised as a photographer and journalist, Sutherland and Gould speak with Sevitsky, who claims he will only defect if he is offered a suede jacket, pants and Raquel Welch. Two MI5 agents offer Sevitsky a Triumph sports car, and the illicit negotiations break down when Sevitsky’s KGB guards spot Sutherland, Gould and the rival MI5 agents. One of the MI5 agents shoots at the KGB guards using a gun disguised as a camera. ‘These guys are crazy. Why don’t they have guns?’, Sutherland observes. ‘Why doesn’t your camera have bullets?’, Gould asks him. ‘Are you crazy? It doesn’t even have film’, Sutherland responds.

Escaping from the gymnasium, Sutherland, Gould and Sevitsky take refuge in a clothes shop. The vain, clothes-obsessed Sevitsky raids the shop’s stock whilst Sutherland and Gould keep watch for the KGB. ‘We ought to kick this bum out of here’, Gould asserts: ‘People bleeding all over the place because he wants a car and suede jacket’. Tiring of Sevitsky’s antics, Gould leads him out of the shop into the hands of the KGB. When Sutherland calls him a coward for doing this, Gould responds: ‘Look, I’m not dying for no money-grubbing acrobat’. Reaching Sutherland’s flat, they discover the door is rigged with a bomb that detonates when the door is opened. ‘I think you’re fired’, Gould observes. ‘But I’m up for promotion’, Sutherland protests. Realising that their lives are threatened by the CIA, the two agents go underground, hiding out with a group of anarchists, led by Sybil (Zouzou), that Sutherland made contact with during a previous operation.  Meanwhile, Martinson meets with Yuri, the head of the Paris branch of the KGB. They discuss the deaths of the two KGB agents during the attempt to help Sevitsky defect. Yuri reminds Martinson of the ‘the agreement of ’72: a corpse for a corpse’. Martinson complains that he doesn’t have to sacrifice two of his agents: ‘All I owe you is two dead American citizens’, Martinson gripes. ‘Who do you have in mind?’, Yuri asks, ‘Maybe Elvis Presley and Walter Kronkite?’ To appease Yuri, Martinson agrees to stage the execution of Sutherland and Gould, his two most useless agents. Meanwhile, Martinson meets with Yuri, the head of the Paris branch of the KGB. They discuss the deaths of the two KGB agents during the attempt to help Sevitsky defect. Yuri reminds Martinson of the ‘the agreement of ’72: a corpse for a corpse’. Martinson complains that he doesn’t have to sacrifice two of his agents: ‘All I owe you is two dead American citizens’, Martinson gripes. ‘Who do you have in mind?’, Yuri asks, ‘Maybe Elvis Presley and Walter Kronkite?’ To appease Yuri, Martinson agrees to stage the execution of Sutherland and Gould, his two most useless agents.

After discovering that they have been marked for death by both the CIA and the KGB, Sutherland and Gould hear of a NOC (non-official cover) list that identifies the names under which Soviet agents within China are hiding. The two bumbling spies travel to London to steal the NOC list from Lippet (Kenneth Griffith), a rival agent. The intention is to use the NOC list as a bargaining chip, with either (or both) the CIA and the KGB. However, things don’t go to plan when Lippet is accidentally killed by his bodyguard and Sutherland and Gould discover that the key to the list, hidden on microdots, is hidden somewhere on Lippet’s beloved pet dog. Whilst trying to discover the key to decode the microdots, Sutherland and Gould discover that they are not only pursued by the CIA and the KGB, but also by Chinese intelligence and Zouzou’s motley band of anarchists, who have become aware that the pair are CIA agents. If there’s one thing Spys has in common with M*A*S*H, other than the casting of Sutherland and Gould, it is its anti-authoritarian streak. The film’s take on the world of espionage is highly cynical. The spies on all sides are depicted as buffoons, bickering over trivialities rather than pulling together to achieve common goals. The CIA and MI5 argue over the defection of Sevitsky, which leads to the athlete’s KGB guards becoming aware of the defection plot, resulting in the deaths of a number of agents on both sides. Sevitsky himself is simply motivated by his own narcissism (he wants to defect because he desires a new wardrobe, a new car, and Raquel Welch), and as Gould observes, the whole event is a farce in itself: before meeting with Sevitsky, Gould notes that, ‘I can’t understand why they [the CIA] wanna have him, though. I could understand a scientist, a writer’. ‘Some guys like freedom, you know?’, Sutherland responds. ‘Oh, yeah, I think he likes money’, Gould quips. The scene in which Martinson and Yuri barter over their agents’ lives, referring to ‘the agreement of ‘72’, in which the death of an agent of one side must be matched by the death of a citizen of the other, is blackly comic and highlights the expendability of the agents and the ways in which human lives are used as pawns in the wider ‘game’ of espionage. (After the second attempt on their life Sutherland observes that, ‘They spent fifty thousand dollars training me and now they try to kill me with a three dollar bomb’.) Likewise, there’s a frightening ring of truth to the joke focusing on Sutherland’s relationship with the group of anarchists headed by Zouzou. Sutherland reveals to Gould that he has contacts within the anarchist faction because he sold the anarchists the dynamite with which they blew up the American embassy a few years earlier. ‘You mean you helped to blow up your own embassy?’, Gould asks in astonishment. ‘We got the ringleaders. That’s what counts’, Sutherland replies in a matter-of-fact manner. ‘Oh yeah, that’s smart’, Gould jokes.  The anarchists fare no better: they are depicted as naïve fools whose commitment to their ‘cause’ is superficial at best. Highlighting the anarchists’ lack of education in their own rhetoric, Sutherland tells Gould that to curry favour with them, he should ‘quote Kropotkin a couple of times’. When Gould reveals he doesn’t know who the anarchist thinker Kropotkin was, Sutherland tells him, ‘Forget about it, quote anybody. Just say it’s Kropotkin’. This leads to Gould quoting Mao Tse-Tung and ascribing the quote to Kropotkin; the anarchists are, of course, completely unaware of this deception. The childlike naivete of the anarchists is reinforced later, when Gould and Sutherland return to Paris after stealing the NOC list from Lippet. They meet with Zouzou’s anarchists, and the driver of the vehicle in which they find themselves wastes time ‘warming’ the engine of the car (‘It’s the breaking in period’, the driver asserts). ‘It’s his father’s new car. He has to be careful’, Sybil informs them. Meanwhile, on the journey, the anarchist driving the car tells Gould, ‘No smoking, please: it will burn the seats’. The anarchists fare no better: they are depicted as naïve fools whose commitment to their ‘cause’ is superficial at best. Highlighting the anarchists’ lack of education in their own rhetoric, Sutherland tells Gould that to curry favour with them, he should ‘quote Kropotkin a couple of times’. When Gould reveals he doesn’t know who the anarchist thinker Kropotkin was, Sutherland tells him, ‘Forget about it, quote anybody. Just say it’s Kropotkin’. This leads to Gould quoting Mao Tse-Tung and ascribing the quote to Kropotkin; the anarchists are, of course, completely unaware of this deception. The childlike naivete of the anarchists is reinforced later, when Gould and Sutherland return to Paris after stealing the NOC list from Lippet. They meet with Zouzou’s anarchists, and the driver of the vehicle in which they find themselves wastes time ‘warming’ the engine of the car (‘It’s the breaking in period’, the driver asserts). ‘It’s his father’s new car. He has to be careful’, Sybil informs them. Meanwhile, on the journey, the anarchist driving the car tells Gould, ‘No smoking, please: it will burn the seats’.

In America, the film seems to have been released in an abbreviated version, running 87 minutes. The DVD released Stateside by Fox seems to contain this abbreviated version of the film. In the UK, however, the film has always had a running time of 100 minutes, and it is this longer cut that is on Network’s DVD. The film here runs for 100:07 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, with anamorphic enhancement. Compositions look fine at this ratio. The image is crisp and detailed. There is some minor damage throughout the film (notably at the edges of the frame during the final sequence), but nothing that would detract from one’s enjoyment of the picture.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. This is clean and clear. Dialogue is audible throughout. However, sadly there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes the film’s trailer (2:05), which attempts to sell the film as a M*A*S*H clone (complete with a tannoy-like voiceover that invites direct comparison with the trailer for Altman’s film), and a stills gallery (0:49). The disc also includes, as a DVD-Rom feature, the film’s original pressbook (as a .PDF file).

Overall

During the mid-1970s, for American audiences, espionage acquired a new type of relevance: the effects of the Watergate scandal were still being felt and, just over a year after the release of Spys, formed the basis for Alan J Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976) (itself also a ‘buddy’ picture of sorts); and films dealing with espionage and elements of spycraft, such as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) and Pakula’s The Parallax View (1974), became increasingly paranoid. Within this context, on its initial release Spys was almost universally panned. Paul Mavis notes that ‘[r]eading the critics of the day, you would have thought the producers had shot a child or something equally evil when they unleashed this movie on an unsuspecting public’ (2011: np). However, there’s an irreverence to Spys that makes it fun to watch. The freewheeling nature of the film is reinforced by its closing sequence, in which Sutherland and Gould stroll away from the devastation they have caused - and the camera, which pans to show their backs to us as they walk away into the distance – whilst humming the 1927 song ‘Side by Side’ (by Gus Kahn and Harry M Woods). It’s a moment that has a strong connection with the closing sequence of Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (also released in 1974), in which, in a pastiche of the famous closing shot of The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1948), Gould’s Philip Marlowe wanders away from the scene of a crime (and the static camera which observes him recede into the distance) whilst, on the soundtrack, ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ (from Busby Berkeley’s 1937 musical Hollywood Hotel) plays. The closing sequences of both Spys and The Long Goodbye have a vaudevillian quality to them, heightened by the fact that at the end of Spys Sutherland and Gould are dressed in morning coats. During the mid-1970s, for American audiences, espionage acquired a new type of relevance: the effects of the Watergate scandal were still being felt and, just over a year after the release of Spys, formed the basis for Alan J Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976) (itself also a ‘buddy’ picture of sorts); and films dealing with espionage and elements of spycraft, such as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) and Pakula’s The Parallax View (1974), became increasingly paranoid. Within this context, on its initial release Spys was almost universally panned. Paul Mavis notes that ‘[r]eading the critics of the day, you would have thought the producers had shot a child or something equally evil when they unleashed this movie on an unsuspecting public’ (2011: np). However, there’s an irreverence to Spys that makes it fun to watch. The freewheeling nature of the film is reinforced by its closing sequence, in which Sutherland and Gould stroll away from the devastation they have caused - and the camera, which pans to show their backs to us as they walk away into the distance – whilst humming the 1927 song ‘Side by Side’ (by Gus Kahn and Harry M Woods). It’s a moment that has a strong connection with the closing sequence of Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (also released in 1974), in which, in a pastiche of the famous closing shot of The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1948), Gould’s Philip Marlowe wanders away from the scene of a crime (and the static camera which observes him recede into the distance) whilst, on the soundtrack, ‘Hooray for Hollywood’ (from Busby Berkeley’s 1937 musical Hollywood Hotel) plays. The closing sequences of both Spys and The Long Goodbye have a vaudevillian quality to them, heightened by the fact that at the end of Spys Sutherland and Gould are dressed in morning coats.

The comparisons that the promotional material suggested between Spys and Altman’s M*A*S*H arguably did the film no favours. Other than the casting of Sutherland and Gould and the anti-authoritarian stance of both films, there is little to connect them. However, fans of Sutherland and Gould will no doubt find the film entertaining enough, though the loose structure of the script is no doubt a result of the script being discarded during production (at least according to Gould, in comments made in the featurette included on the US DVD release). The presentation on this DVD is very good, but sadly there’s little in the way of contextual material. References: Mavis, Paul, 2011: The Espionage Filmography. London: McFarland Pettigrew, Terence, 1982: British Film Character Actors: Great Names and Memorable Moments. London: Rowman & Littlefield This review has been kindly sponsored by:  >

|

|||||

|