|

|

Victim (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th August 2014). |

|

The Film

Victim (Basil Dearden, 1961) Victim (Basil Dearden, 1961)

The first film to examine homosexuality directly, Basil Dearden’s Victim (1961) also marked a turning point in the career of its star, Dirk Bogarde. Bogarde plays Melville Farr, a barrister who is about to be promoted to QC. Farr, who is married to Laura (Sylvia Syms), becomes embroiled in a mystery when a young man, Jack ‘Boy’ Barrett (‘Boy Barrett’ was the film’s original title; Peter McEnery), is arrested by the police. However, before he is arrested Barrett telephones Farr for help. Farr turns Barrett away, telling him ‘If I hear from you again, I shall call the police. Do you understand? That’s absolutely final’. Barrett also turns to several other men for help: Harold Doe (Norman Bird), the owner of a bookshop; Phip (Nigel Stock), a car salesman; and Frank (Alan Howard) and his girlfriend Sylvie (Dawn Beret). Frank offers Barrett a bed for the night, but Sylvie gripes, ‘Why can’t he stick with his own sort?’ Barrett is eventually captured by the police. It is revealed that he was being sought for stealing money from the construction company for which he works. When Barrett is arrested, he is carrying a scrapbook that he asked his friend Eddy (Donald Churchill) to retrieve from his bedsit. The scrapbook contains newspaper cuttings relating to Farr. The police call Farr, but it is too late: Barrett has committed suicide in his cell. The police surmise that Barrett led a sad and lonely life: detectives observe that he ‘never went anywhere’ and ‘Lived out of tins in his room’. Barrett’s frugal lifestyle conflicts with the knowledge that he was stealing money from his employers, and the detective in charge of the investigation, Detective Inspector Harris (John Barrie), comes to the conclusion that Barrett was being blackmailed.  When a compromising photograph depicting Farr in his car with Barrett comes to light, Farr realises that Barrett was stealing the money from his employers to pay the blackmailers, thus protecting Farr. Faced with the realisation that Barrett was trying to protect him, Farr’s guilt provokes him into taking action against the blackmailers. Farr enlists Eddy’s help in capturing the blackmailers. Eddy reasons that the blackmailers didn’t go after Farr because Farr is a barrister and would ferret the blackmailers out. ‘Why go looking for trouble?’, Farr notes. ‘If I hadn’t been trying so bloody hard to avoid trouble, this might never have happened’, Farr observes, ‘But it has and they’re not going to get away with it’. Farr tells Eddy to visit the pub that Barrett frequented, The Chequers (which seems to be a place where gay men socialise), and ‘watch for fear. Fear is the oxygen of blackmail. Barrett was paying. Others are. Find me one’. When a compromising photograph depicting Farr in his car with Barrett comes to light, Farr realises that Barrett was stealing the money from his employers to pay the blackmailers, thus protecting Farr. Faced with the realisation that Barrett was trying to protect him, Farr’s guilt provokes him into taking action against the blackmailers. Farr enlists Eddy’s help in capturing the blackmailers. Eddy reasons that the blackmailers didn’t go after Farr because Farr is a barrister and would ferret the blackmailers out. ‘Why go looking for trouble?’, Farr notes. ‘If I hadn’t been trying so bloody hard to avoid trouble, this might never have happened’, Farr observes, ‘But it has and they’re not going to get away with it’. Farr tells Eddy to visit the pub that Barrett frequented, The Chequers (which seems to be a place where gay men socialise), and ‘watch for fear. Fear is the oxygen of blackmail. Barrett was paying. Others are. Find me one’.

Eddy begins to feed information about the blackmail victims to Farr, who sets about interviewing them. Farr soon comes into contact with the prime culprit, the softly-spoken but threatening Sandy Youth (Derren Nesbitt). Meanwhile, Laura becomes increasingly aware of Farr’s relationship with Barrett. She eventually leaves Barrett, finding refuge in the home of her brother, widower Scott (Alan MacNaughton), who lives alone with his young son Ronnie. When ‘FARR IS QUEER’ is painted on Farr’s garage, the stakes are raised. Farr is faced with a dilemma: if he pays the blackmailers, ‘I buy security… of a sort’; but if he hands the blackmailers to the police, there will be a scandal that will almost definitely mean the end of his career. Andy Medhurst noted that the intentions of Victim ‘were to support the recommendations of the Wolfenden Report [of 1957], which advocated the partial decriminalization of male homosexual acts, but the emotional excess of Bogarde’s performance […] pushes the text’ into the realm of a ‘passionate validation of the homosexual option’ (quoted in Coldstream, : np). In Screened Out: Playing Gay in Hollywood from Edison to Stonewall (2003), Richard Barrios declares that in its focus on the blackmailing of gay men, Victim ‘occupies a special Olympian niche’ and is ‘an example of true guts in a business rarely noted for courageous endeavour’ (301). Barrios argues that the film offered ‘a genuine public service, railing against and eventually helping to overturn Britain’s archaic laws on homosexuality’ (ibid.). (In England, homosexual acts, committed between two men over the age of 21 and in private, were finally decriminalised by the Sexual Offences Act of 1967.) For its direct and sympathetic examination of homosexuality, in America the film was released without the Production Code seal, with the profoundly reactionary review in Time complaining hysterically that ‘[e]verybody in the picture who disproves of homosexuals proves to be an ass, a dolt, or a sadist. Nowhere does the film suggest that homosexuality is a serious (but often curable) neurosis that attacks the biological basis of life itself. “I can’t help the way I am”, says one of the sodomites in this movie [….] And the scriptwriters […] accept this sick-silly self-delusion as a medical fact’ (quoted in Burton & O’Sullivan, 2009: 248). The rhetoric of the review in Time matches the hysteria of the film’s two villains, Sandy Youth and Miss Benham, the middle aged spinster with whom Sandy is in league. (At the end of the film, Miss Benham rages that ‘They [homosexuals] disgust me [….] They’re everywhere, everywhere you turn. The police do nothing; someone’s got to make them pay for their filthy blasphemy’.) Farr’s insistence on doing his part to destroy the blackmail ring despite not being directly threatened by it (it is suggested that though the blackmailers know of his sexuality, they dare not blackmail him owing to his status as a barrister), resulting in the self-destruction of his legal career (as the film opens, he is about to become a QC), bestows on the character a ‘heroic status’ (Mayer & McDonnell, 2007: 433). By contrast, the film’s blackmailers, Sandy Youth and Miss Benham, are depicted as ‘psychotic’ (in terms of their twisted worldview) and as ‘demented grotesques’, which ‘serves to foreground’ the film’s ‘social message and reflects the intentions of script writer Janet Green to assimilate a social message into the conventions of the crime film’ (ibid.). This was an agenda which Dearden and producer Michael Relph were sympathetic towards, having achieved something similar with Dearden’s Sapphire, which in the guise of a crime picture had explored racial tensions in London. Both Sapphire and Victim ‘focused on a topical and controversial theme’, employing ‘the same kind of crime-whodunit formula to reveal and explore its distinctive, “hidden” social problem agenda: male homosexuality, persecution, blackmail and the law’ (Burton & O’Sullivan, op cit.: 232). However, where Sapphire focused on a police investigation, the police themselves play only a tangential role in Victim: the bulk of the film focuses on Farr’s crusade against the blackmailers, which puts his own career on the line.  Victim took the form of ‘a well-crafted commercial thriller’ (Barrios, op cit.: 302). The ‘unflinching treatment’ of the subject matter, and the casting of Bogarde in the role of the repressed gay barrister Melville Farr, made the film simultaneously ‘more viable and more risky’ (ibid.). During the 1950s, Bogarde had largely been cast in ‘a succession of pleasant, somewhat sexless, roles’ under a seven year contract with Rank, in films such as Doctor in the House (Ralph Thomas, 1954) (Mayer, 2003: 34). The majority of Bogarde’s roles prior to Victim had been ‘romantic gloss’, and Bogarde had referred to himself during this part of this screen acting career as ‘the male Loretta Young’ (Bogarde, qoted in Barrios, op cit.: 302). With Victim, Bogarde felt that he ‘had achieved what I had longed to do for so long, to be in a film which disturbed, educated, and illuminated as well as merely giving entertainment’ (quoted in Burton & O’Sullivan, op cit.: 247). However, Bogarde’s first major role, as the sexually sadistic gangster Tom Riley in The Blue Lamp (Basil Dearden, 1949), ‘foreshadowed the more perverse characterizations that were found in his roles after Victim in 1961’ (Mayer, op cit.: 304). In provocative films such as The Servant (Joseph Losey, 1963), Accident (Losey, 1967), Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti, 1970) and The Night Porter (Liliana Cavani, 1973), Bogarde ‘left behind the “matinee idol” roles for greater challenges’ in less conventional, more ‘difficult’ performances, often for European rather than British or American directors (ibid.). However, Glyn Davis has noted that ‘[i]n retrospect, it’s also quite astonishing how many of Bogarde’s roles were – more or less explicitly – “queer” or “gay”’, even prior to Victim: ‘The Singer Not the Song [Roy Ward Baker, 1961], The Spanish Gardener [Philip Leacock, 1956], and The Servant, along with other titles, were all homoerotically charged’ (ibid.). Victim took the form of ‘a well-crafted commercial thriller’ (Barrios, op cit.: 302). The ‘unflinching treatment’ of the subject matter, and the casting of Bogarde in the role of the repressed gay barrister Melville Farr, made the film simultaneously ‘more viable and more risky’ (ibid.). During the 1950s, Bogarde had largely been cast in ‘a succession of pleasant, somewhat sexless, roles’ under a seven year contract with Rank, in films such as Doctor in the House (Ralph Thomas, 1954) (Mayer, 2003: 34). The majority of Bogarde’s roles prior to Victim had been ‘romantic gloss’, and Bogarde had referred to himself during this part of this screen acting career as ‘the male Loretta Young’ (Bogarde, qoted in Barrios, op cit.: 302). With Victim, Bogarde felt that he ‘had achieved what I had longed to do for so long, to be in a film which disturbed, educated, and illuminated as well as merely giving entertainment’ (quoted in Burton & O’Sullivan, op cit.: 247). However, Bogarde’s first major role, as the sexually sadistic gangster Tom Riley in The Blue Lamp (Basil Dearden, 1949), ‘foreshadowed the more perverse characterizations that were found in his roles after Victim in 1961’ (Mayer, op cit.: 304). In provocative films such as The Servant (Joseph Losey, 1963), Accident (Losey, 1967), Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti, 1970) and The Night Porter (Liliana Cavani, 1973), Bogarde ‘left behind the “matinee idol” roles for greater challenges’ in less conventional, more ‘difficult’ performances, often for European rather than British or American directors (ibid.). However, Glyn Davis has noted that ‘[i]n retrospect, it’s also quite astonishing how many of Bogarde’s roles were – more or less explicitly – “queer” or “gay”’, even prior to Victim: ‘The Singer Not the Song [Roy Ward Baker, 1961], The Spanish Gardener [Philip Leacock, 1956], and The Servant, along with other titles, were all homoerotically charged’ (ibid.).

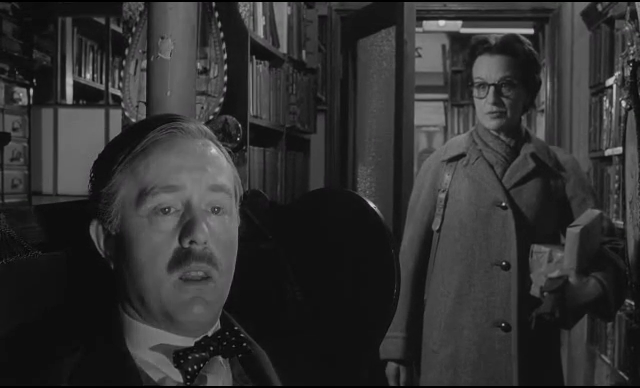

Of course, Bogarde himself was gay, although he was very much in the closet. With the material very close to his heart, Bogarde ‘shouldered much of the responsibility for keeping the production [of Victim] on track despite a great deal of resistance’ and also ‘contributed to the script’ (Barrios, op cit.: 302). Bogarde’s contributions to the film’s script included the first scene in a film in which a man declared his love for another man. Bogarde later reflected that, ‘it was the first film in which a man said “I love you” to another man. I wrote that scene in. I said, “There’s no point in half-measures. We either make a film about queers or we don’t”’ (quoted in Ison, 2003: 206). The opening sequence establishes Barrett’s status as a hunted man. We are shown a building site. A car pulls up, and detectives exit the car and enter the site office. Barrett watches from above, looks profoundly worried, and descends in a lift. He flees the site and telephones the house in which he lodges, speaking to his friend Eddy, asking Eddy to retrieve the parcel that is secreted at the back of Barrett’s wardrobe. From here, Barrett contacts his friends and acquaintances, desperately seeking their help as he attempts to flee the country: Barrett’s former lovers Phip and Harold Doe; Farr, with whom Barrett was infatuated; and Barrett’s friend Frank, who is not homosexual but who is nonetheless entirely sympathetic with Barrett. Farr, of course, turns Barrett away, apparently believing that Barrett is attempting to blackmail him. However, as the narrative progresses and Farr realises that Barrett was the victim of a blackmail plot and was in fact turning to Farr for help, Farr’s guilt motivates him to becoming involved in the hunt for the blackmailers. Later in the film, Laura comments on this guilt, observing, ‘That thought [that Farr is somehow responsible for Barrett’s suicide] will remain with you for the rest of your life. I don’t think there’s going to be room for me as well’.  The early sequences of the film highlight the extent to which the gay characters in the narrative must, in order to function within society (and, of course, avoid being imprisoned), repress a core part of themselves. In these early sequences, discussion of homosexual desire is coded and oblique. When Barrett first meets with Doe, in Doe’s flat, Barrett makes Doe promise ‘never to tell anyone’. Barrett is referring, obliquely, to his brief fling with Farr. Doe asks obtusely if there is anything to ‘tell’. ‘Well, yes’, Barrett responds, ‘You remember. Back last spring… When I… When I left’. Barrett’s hesitation underscores the difficulty in confronting the gay relationship between Barrett and Doe head on. ‘Oh, that’, Doe responds nonchalantly, ‘Well, there’s no fun in gossip if you don’t mention names. You never did, did you?’ Doe ends the conversation with a subtle threat: ‘Not that secrets don’t have a horrid way of creeping out’. As the conversation progresses, Doe makes tea in the teapot that was in the foreground of the shot depicting Barrett and Doe entering Doe’s flat (staged in depth, with the teapot in the foreground and, in the background, Doe and Barrett entering the door). As he talks, Doe covers the teapot with a tea cosy: an obvious visual metaphor for repression, the keeping of desire ‘under wraps’. The early sequences of the film highlight the extent to which the gay characters in the narrative must, in order to function within society (and, of course, avoid being imprisoned), repress a core part of themselves. In these early sequences, discussion of homosexual desire is coded and oblique. When Barrett first meets with Doe, in Doe’s flat, Barrett makes Doe promise ‘never to tell anyone’. Barrett is referring, obliquely, to his brief fling with Farr. Doe asks obtusely if there is anything to ‘tell’. ‘Well, yes’, Barrett responds, ‘You remember. Back last spring… When I… When I left’. Barrett’s hesitation underscores the difficulty in confronting the gay relationship between Barrett and Doe head on. ‘Oh, that’, Doe responds nonchalantly, ‘Well, there’s no fun in gossip if you don’t mention names. You never did, did you?’ Doe ends the conversation with a subtle threat: ‘Not that secrets don’t have a horrid way of creeping out’. As the conversation progresses, Doe makes tea in the teapot that was in the foreground of the shot depicting Barrett and Doe entering Doe’s flat (staged in depth, with the teapot in the foreground and, in the background, Doe and Barrett entering the door). As he talks, Doe covers the teapot with a tea cosy: an obvious visual metaphor for repression, the keeping of desire ‘under wraps’.

Farr’s repression of his own gay identity is also represented visually. Repeatedly, he is shot in chiaroscuro lighting, part of his face in shadow, a visual representation of the aspect of himself that he has hidden. When Laura tells Farr that Barrett called on the telephone, Farr is shown standing, half-turned away from Laura, his face (and reaction) concealed by shadows. A common element of the compositions within the film is a shot of two characters (often Farr and Laura), both facing the camera, one standing slightly in front of the other (and thus with her/his back to the other), hiding secrets and their non-verbal responses to the other’s statements and questions.   After these oblique references to homosexuality, the topic is first confronted directly when Detective Inspector Harris speaks with Farr about Barrett’s arrest. After Harris has shown Farr the scrapbook that was in Barrett’s possession when the police found him in a motorway café, Farr asserts that Barrett had begun to stalk him. Harris asks Farr if he knows of any reason why Barrett may have been blackmailed: ‘Of course, you knew that he was a homosexual?’, Harris asks. ‘I had formed that impression’, Farr responds. ‘You know also, sir, that almost ninety per cent of blackmail cases have a homosexual angle?’, Harris says. This scene reputedly had a profound impact on the young Terence Davies, when he saw Victim in the cinema: ‘That moment when Dirk is in the police station and the policeman says, “You of course knew that Barratt was a homosexual?” And the camera tracks in on Dirk and he says, “Yes, I gathered that.” “Homosexual” was a word that no one ever said. The word in those days was “queer”, which was derogatory and very unpleasant [….] And I just thought, “And yes, and so am I”’ (quoted in Coldstream, 2011: np).  The dialogue between Harris and Bridie (John Cairney), one of his detectives, offers a dialectic on attitudes towards a homosexuality. Harris offers a sympathetic approach to the victims of the blackmail plot, whilst Bridie suggests that homosexuality is aberrant. ‘If only those unfortunate devils would come to us in the first place’, Harris notes in one scene. ‘If only they led more normal lives, they wouldn’t need to come at all’, Bridie adds. ‘If the law punished every abnormality, we’d be kept pretty busy, son’, Harris notes. ‘Even so, sir’, Bridie protests, ‘this law was made for very good reason. If it were changed, other “weaknesses” would follow’. ‘I can see you’re a true puritan, Bridie’, Harris tells him. ‘There’s nothing wrong with that, sir’, Bridie suggests. ‘Of course not. But there was a time when that was against the law, you know’, Harris reminds him. The dialogue between Harris and Bridie (John Cairney), one of his detectives, offers a dialectic on attitudes towards a homosexuality. Harris offers a sympathetic approach to the victims of the blackmail plot, whilst Bridie suggests that homosexuality is aberrant. ‘If only those unfortunate devils would come to us in the first place’, Harris notes in one scene. ‘If only they led more normal lives, they wouldn’t need to come at all’, Bridie adds. ‘If the law punished every abnormality, we’d be kept pretty busy, son’, Harris notes. ‘Even so, sir’, Bridie protests, ‘this law was made for very good reason. If it were changed, other “weaknesses” would follow’. ‘I can see you’re a true puritan, Bridie’, Harris tells him. ‘There’s nothing wrong with that, sir’, Bridie suggests. ‘Of course not. But there was a time when that was against the law, you know’, Harris reminds him.

Bridie’s reactionary feelings towards the blackmail victims are not his alone: they are shared by the bartender at The Chequers, the pub frequented by Barrett and his clique, who asks one of the female customers, Madge (Mavis Villiers), ‘I don’t know how you can stand them’ – referring, of course, to the gay customers of the pub. ‘I thought they amused you’, Madge says. ‘Oh, they’re good for a laugh, all right’, the bartender responds, ‘very witty at times. Generous too. But I hate their bloody guts’. ‘They’re just not quite normal, dear’, Madge offers, sympathetic to her gay friends but is patronising nonetheless, ‘What’s it to you? If they had gammy legs or something, you’d feel sorry for them’. ‘Sorry for them? Not me’, the bartender responds. ‘It’s always excuses [….] Environment, too much love as kids, too little love as kids, they can’t help it, it’s part of their nature. Well, to my mind, it’s the weak, rotten part of nature, and if they ever make it legal, they may as well license every perversion’, his ‘slippery slope’/‘thin end of the wedge’ rhetoric echoing that of Bridie in his debate with Harris. (Ironically, this rhetoric was also echoed in the famous review of the film that appeared in Time, quoted above.) Elsewhere, in the scene alluded to in the Time review, gay sexuality is depicted as an essential part of the identity of these individuals, something which they are born with. ‘I can’t help the way I am’, Henry (Charles Lloyd Pack), a barber who is being blackmailed, tells Farr, ‘but the law says I’m a criminal’. Henry has been to prison four times. ‘I couldn’t go through that again’, Henry informs Farr, ‘not at my age […] I’ve made up my mind to be “sensible”, as the prison doctor used to say. I don’t care how lonely, but sensible’. Henry sees himself as the victim of his own nature: ‘Nature played me a dirty trick’, he protests, ‘I’m going to see I get a few years of peace and quiet in return […] Tell them there’s no magic cure for who we are, least of all behind prison bars. I’ve come to feel like a criminal, an outlaw’. However, Farr offers a challenge to this essentialist argument about sexuality: Farr has hidden his homosexuality, and has lived seemingly happily with his wife Laura. Nevertheless, prior to their marriage Farr had a relationship with another man, Stainer. When Laura becomes aware that Farr may have had a relationship with Barrett too, she confronts him, Farr dismissing Barrett’s infatuation with him as a form of ‘hero worship’. ‘I’d rather know than guess’, Laura complains, telling Farr, ‘You haven’t changed. In spite of our marriage, in your innermost feelings you’re still the same [….] You were attracted to that boy as a man would be to a girl’. Later, she confronts him more directly, telling him that the ‘impulse’ Farr experienced with Stainer is ‘still there’. ‘I’m not a lifebelt for you to cling to’, Laura tells her husband, ‘I’m a woman, and I want to be loved for myself’. (In an earlier sequence, it is suggested that Farr married Laura ‘like an alcoholic takes a cure’.)  Sometimes the dialogue threatens to become overly didactic. At one point, Harris says that, ‘Well, there’s no doubt that a law which sends homosexuals to prison offers unlimited opportunities to blackmail [….] Blackmail’s the simplest of crimes when we have the co-operation of the victim; almost impossible when we haven’t’. Later, Farr confronts Calloway (Dennis Price), an actor who is being blackmailed. Farr tells Calloway, ‘Paying the blackmail won’t alter the law: it’ll only encourage the blackmailer’. ‘If we don’t pay, ten to one, we land in jail’, Calloway protests, ‘with out crime, so-called, damn nearly parallel with robbery with violence’. Sometimes the dialogue threatens to become overly didactic. At one point, Harris says that, ‘Well, there’s no doubt that a law which sends homosexuals to prison offers unlimited opportunities to blackmail [….] Blackmail’s the simplest of crimes when we have the co-operation of the victim; almost impossible when we haven’t’. Later, Farr confronts Calloway (Dennis Price), an actor who is being blackmailed. Farr tells Calloway, ‘Paying the blackmail won’t alter the law: it’ll only encourage the blackmailer’. ‘If we don’t pay, ten to one, we land in jail’, Calloway protests, ‘with out crime, so-called, damn nearly parallel with robbery with violence’.

The plot by Sandy Youth and Miss Benham is depicted as a moral crusade, a witch hunt. When Barrett approaches Frank for help, much to the chagrin of Frank’s girlfriend Sylvie, Frank tells Barrett, ‘Well, it used to be witches. At least they don’t burn you’. Although Sandy Youth and Miss Benham seem to pick their targets carefully, choosing those who will offer them the least resistance (Barrett, care salesman Phip, actor Calloway), Sandy Youth (in a creepy, soft-spoken performance by Nesbitt) observes at one point that, ‘The more they [the victims] have got, the more they fight to keep it’. Sandy Youth and Miss Benham’s blackmail plot is facilitated the legislation against (and the prejudice towards) homosexuality, something the film confronts directly. ‘Someone once called this law against homosexuals the “blackmailers’ charter”’, Harris observes at one point. ‘Is that how you feel about it?’, Farr asks him. ‘I’m a policeman, sir. I don’t have feelings’, Harris responds. This echoes an earlier comment by Farr when, asked by one of the blackmail victims, ‘Do you support the law?’, Farr responds by asserting simply that ‘I am a lawyer’. After Farr makes his first contact with Barrett via telephone, and Barrett turns him away, the camera pans down from Barrett, following his gaze to reveal his desk and, on it, a copy of the Law Times and a framed photograph of Laura. The mise-en-scene reinforces the twin agents of Barrett’s repression of his homosexual desire: the law and his heterosexual relationship with Laura. Both Farr and Harris demonstrate an objectivity towards the case that stops short of criticising the law – until the end of the film, where, after Sandy Youth and Miss Benham have been arrested, Farr asserts that he will see justice done, even if it means the end of his career. He will be unable to maintain his anonymity during the case, but ‘I believe that if I go into court as myself, I can draw attention to the fault in the existing law’.

Video

The use of short focal lengths (with short hyperfocal distances) give the compositions remarkable depth. For example, when Barrett first meets with Harold Doe, as Barrett enters Doe’s flat (which appears to be situated behind his bookshop), a teapot is framed in the foreground whilst deep in the background, Barrett and Doe enter the room through a door – Doe will later cover this teapot in an act which acts as a visual metaphor for the repression of his sexuality. The use of chiaroscuro lighting throughout the film invites comparison with the expressionistic photography in American films noirs such as Joseph H Lewis’ The Big Combo (1955). Victim is an expressively shot film. (There are a couple of optical blow-ups which look quite clumsy, however, such as a close up of Sylvia Syms at 58:06.)

The monochrome image is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation (from an incredibly clean source) evidences very good tonality and contrast. There are strong mid-tones, highlights retain detail and blacks don’t appear to be crushed. However, there seems to be intermittent evidence of digital sharpening and noise reduction – which may or may not be a product of the encode to disc. These don’t overwhelm the image, however, and in terms of detail and tonality within the monochrome photography, this Blu-ray is still a big step up from the various DVDs that are available. Nevertheless, there is certainly room for improvement. (NB. Current screen grabs are for illustration purposes only and are not intended to reflect the quality of Network’s Blu-ray releases. More representative screen grabs will be added in a few days.)

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossy Dolby Digital two-channel mono track. The film’s sound design isn’t ‘showy’, by any means, but the absence of a lossless track is an oversight. The Dolby Digital track on this Blu-ray feels very cramped, especially when the film’s score takes over the mix. Optional English subtitles (for the Hard of Hearing) are provided.

Extras

The disc includes a good range of contextual material, including: Trailer (2:18). Dirk Bogarde in Conversation (28:36). This is the famous interview with Dirk in which he declared himself ‘free of them’ – referring to Rank and asserted that of the thirty-five films he had made under contract to Rank, he was only happy with a mere six of them. Galleries: - Production Image Gallery (5:03) - Behind the Scenes Image Gallery (1:50) - Portrait Image Gallery (2:39) - Promotional Image Gallery (2:05) These galleries do exactly what they say on the tin.

Overall

Victim is an excellent, ground-breaking film, daring for its time and even today. Bogarde is brilliant in the role of Farr, and the rest of the cast are uniformly strong (especially Nesbitt as the creepy, insidious Sandy Youth). The monochrome photography has the richness of the photography associated with the best films noirs being produced in America. Victim is an excellent, ground-breaking film, daring for its time and even today. Bogarde is brilliant in the role of Farr, and the rest of the cast are uniformly strong (especially Nesbitt as the creepy, insidious Sandy Youth). The monochrome photography has the richness of the photography associated with the best films noirs being produced in America.

This Blu-ray disc contains a solid presentation of the film that has some issues. There’s no doubt about the fact that it’s far and away an improvement on the various DVDs, but there is some evidence of noise reduction and sharpening here and there (which, as stated above, may or may not simply be a product of a problematic encode). The absence of a lossless audio option is also to be regretted. Nevertheless, there is some good contextual material – but a retrospective interview with someone like John Coldstream (Bogarde’s biographer, whose excellent monograph on Victim was published in the BFI’s ‘Film Classics’ range a few years ago) would have been a welcome addition. There’s more than enough here to make this disc a solid recommendation, but be advised that there’s room for improvement in terms of both video and audio. References: Barrios, Richard, 2003: Screened Out: Playing Gay in Hollywood from Edison to Stonewall. London: Routledge Burton, Alan & O’Sullivan, Tim, 2009: The Cinema of Basil Dearden and Michael Relph. Edinburgh University Press Coldstream, John, 2011: Dirk Bogarde: The Authorised Biography. London: Hachette Davis, Glyn, 2008: ‘Trans-Europe Success: Dirk Bogarde’s International Queer Stardom’. In: Griffiths, Robin (ed): Queer Cinema in Europe. Bristol: Intellect Books: 167-80 Dyer, Richard, 2013: The Matter of Images: Essays on Representations. London: Routledge (Second Edition) Ison, John, 2003: ‘Dirk Bogarde’. In: Haggerty, George & Zimmerman, Bonnie (eds), 2003: Gay Histories and Cultures. London: Garland Science: 206 Mayer, Geoff, 2003: Guide to British Cinema. Connecticut: Greenwood Press Mayer, Geoff & McDonnell, Brian, 2007: Encyclopedia of Film Noir. Connecticut: Greenwood Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:  >

|

|||||

|