|

|

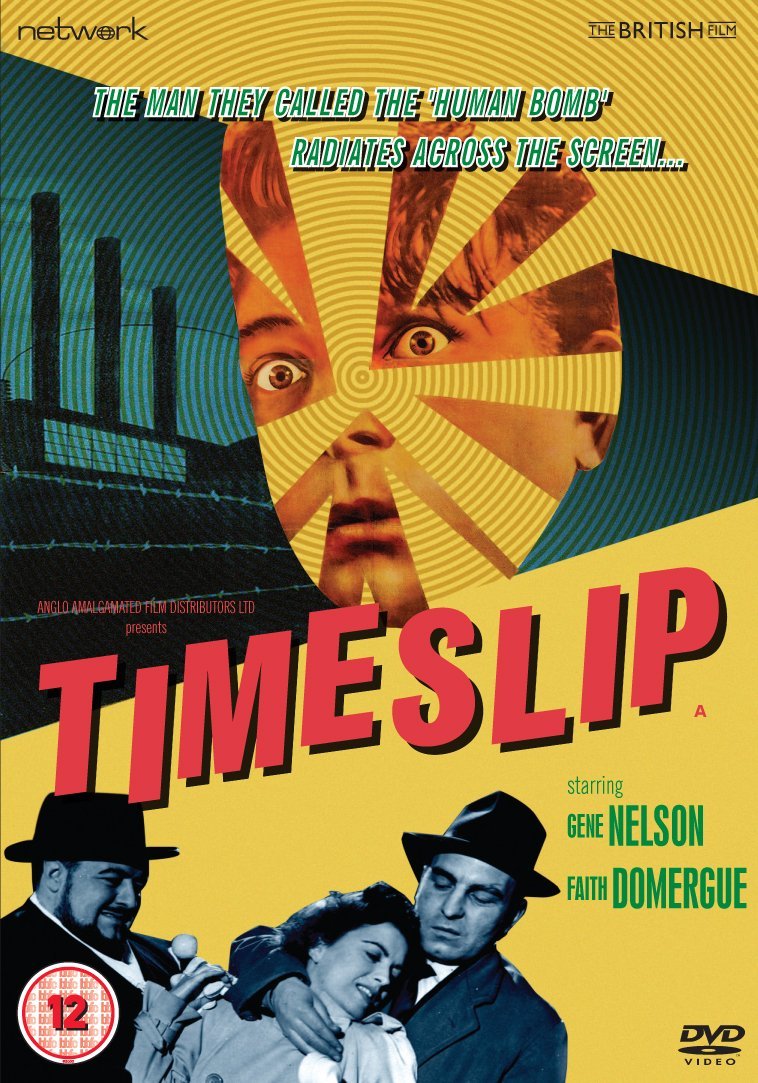

Timeslip AKA The Atomic Man AKA Time Slip

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st October 2014). |

|

The Film

Timeslip (The Atomic Man, Ken Hughes, 1955) Timeslip (The Atomic Man, Ken Hughes, 1955)

Directed by Ken Hughes – whose ‘showy’ later work such as Cromwell (1970), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) and Casino Royale (1967) belies his work on fairly low-key crime films during the fifties (including Wide Boy, 1952; Black 13, 1953; and The House Across the Lake, 1954) – Timeslip was written by Charles Eric Maine. The film was one of several stabs that Maine had at these themes. Originally, the idea which evolved into Timeslip had been presented as a 30 minute television play (with the title presented as ‘Time Slip’) that was broadcast on the BBC in November, 1953. The plotting of Maine’s ‘Time Slip’ teleplay was admittedly thin, focusing simply on a man, John Mallory (Jack Rodney), who dies and is brought back to life with adrenalin, only for those around Mallory to discover that he is now living 4.7 seconds into the future, enabling him to answer questions before they are even asked. For this film adaptation, Maine added an espionage element: the man living in the future is, in this adaptation, a scientist named Dr Stephen Rayner (Peter Arne) whose assassination was attempted by South American agents attempting to thwart the scientist’s research into manufacturing chemical elements within a laboratory. Rayner is shot in the back at night, in an exciting chase sequence by the Thames. He is revived in the hospital but seems to be unable to do anything but babble nonsense in response to the questions that he is asked – later revealed to be owing to the fact that he is now living 7.5 seconds into the future, thus answering questions that, in the diegetic present, are yet to be asked. Rayner’s case is investigated by Mike Delaney (Gene Nelson), a journalist working for a lifestyle magazine. Delaney is unhappy with his position, more suited to an investigative position than coverage of lifestyle issues, but is nevertheless upset when the time he devotes to the Rayner case results in Delaney losing his job.  Delaney is assisted in his investigation by his girlfriend, photographer Jill Rabowski (Faith Domergue) – who shows an impressive ability with a Barnack-era Leica. Initially, Rabowski’s shots of Rayner arouse Delaney’s suspicion and interest when they reveal a ghosting around the image – dismissed chauvinistically by some of Rabowski’s colleagues to be caused by Rabowski’s technique (‘I’ve been loading film since I was knee-high to a tripod’, Jill asserts at one point). This is later revealed to be a by-product of Rayner’s mysterious research into producing chemical elements: ‘Isn’t that what the alchemists used to call “transmutation”?’, a detective asks when he hears about the nature of Rayner’s work in the lab. Ultimately, Delaney’s investigation reveals that the attempt on Rayner’s life was commissioned by a South American dealer in tungsten, who threatens to be put out of business if Rayner’s experiments prove to be successful. This shadowy foreign businessman has replaced Rayner with a double and plans to blow up Rayner’s lab with a bomb, thus preventing anyone from following Rayner’s research. However, Delaney and Rabowski place themselves in danger in an attempt to bring this criminal to justice. Delaney is assisted in his investigation by his girlfriend, photographer Jill Rabowski (Faith Domergue) – who shows an impressive ability with a Barnack-era Leica. Initially, Rabowski’s shots of Rayner arouse Delaney’s suspicion and interest when they reveal a ghosting around the image – dismissed chauvinistically by some of Rabowski’s colleagues to be caused by Rabowski’s technique (‘I’ve been loading film since I was knee-high to a tripod’, Jill asserts at one point). This is later revealed to be a by-product of Rayner’s mysterious research into producing chemical elements: ‘Isn’t that what the alchemists used to call “transmutation”?’, a detective asks when he hears about the nature of Rayner’s work in the lab. Ultimately, Delaney’s investigation reveals that the attempt on Rayner’s life was commissioned by a South American dealer in tungsten, who threatens to be put out of business if Rayner’s experiments prove to be successful. This shadowy foreign businessman has replaced Rayner with a double and plans to blow up Rayner’s lab with a bomb, thus preventing anyone from following Rayner’s research. However, Delaney and Rabowski place themselves in danger in an attempt to bring this criminal to justice.

The film is an entertaining little picture with some snappy dialogue: upon discovering the ‘body’ of Rayner, later revealed to still be alive, he is described as ‘like a cut of fish’. Light touches are sprinkled thoughout: for example, at one point Delaney is asked by a blonde secretary, ‘Can I get you anything?’ ‘Like excited?’, Delaney queries. ‘Oh, Mr Delaney’, the secretary giggles. Delaney and Rabowski are sympathetic protagonists – Rabowski arguably more so than Delaney. Delaney seems trapped within his work for the lifestyle magazine that employs him but is nevertheless devastated when he loses his job, owing to his tenacious investigation of the Rayner case. Nevertheless, Delaney’s work for the magazine is what allows him access to information that the police don’t have: he is the one who recognises Rayner and notices the strange aura that is exhibited around Rayner on photographs that are taken of him (later revealed to be a product of Rayner’s handling of radioactive isotopes). The police initially believe the case to be far more simple than it really is: ‘You know, Mr Delaney’, a policeman tells Delaney when he insists on asking more questions, ‘You’re like a lot of journalists. You don’t believe anything unless there’s a big mystery’. Delaney, and journalists generally, is also seen as a hindrance by the police: ‘Journalists are like dandruff’, a police detective asserts at one point, whilst explaining to a junior office why he allowed Delaney and Rabowski to take a photograph of Rayner, ‘You finally give up trying to get them out of your hair’. Delaney is also the one who deduces that Rayner is living 7.5 seconds into the future, after listening to a tape recording of his interview with Rayner. (‘Your patient’s ahead of time, Dr Preston’, Delaney tells the doctor who is caring for Rayner.)  One of the more interesting aspects of the film is the extent to which it gives Rabowski an active role in the development of the narrative. She begins the film as little more than Delaney’s girlfriend and helper, a traditionally passive role for a female character; but later in the film she becomes increasingly central to the attempts made to bring Rayner’s attackers to justice. She has a wonderful scene in which, visiting a pub, she experiences a ‘Eureka’ moment whilst watching the barman break ice with an ice-pick. She asks to borrow this ice-pick, planning on using it to break into the office of the South American tungsten dealer. The barman happily agrees, but then quietly asserts, ‘If you’re thinking of murdering someone, there’s a much cleaner way than with an ice-pick’, whilst subtly placing a bottle of poison on the counter. ‘Well, if this doesn’t work out, I’ll let you know’, Rabowski counters. ‘I was just giving you a bit of friendly advice, miss’, the barman responds. It’s a brief scene that adds little to the narrative but, whilst outwardly light in content, highlights the undertones of violence that seem to be omnipresent throughout the film, from the opening chase alongside the Thames at nighttime onwards – making this a curious and entertaining example of a British film noir-style picture. One of the more interesting aspects of the film is the extent to which it gives Rabowski an active role in the development of the narrative. She begins the film as little more than Delaney’s girlfriend and helper, a traditionally passive role for a female character; but later in the film she becomes increasingly central to the attempts made to bring Rayner’s attackers to justice. She has a wonderful scene in which, visiting a pub, she experiences a ‘Eureka’ moment whilst watching the barman break ice with an ice-pick. She asks to borrow this ice-pick, planning on using it to break into the office of the South American tungsten dealer. The barman happily agrees, but then quietly asserts, ‘If you’re thinking of murdering someone, there’s a much cleaner way than with an ice-pick’, whilst subtly placing a bottle of poison on the counter. ‘Well, if this doesn’t work out, I’ll let you know’, Rabowski counters. ‘I was just giving you a bit of friendly advice, miss’, the barman responds. It’s a brief scene that adds little to the narrative but, whilst outwardly light in content, highlights the undertones of violence that seem to be omnipresent throughout the film, from the opening chase alongside the Thames at nighttime onwards – making this a curious and entertaining example of a British film noir-style picture.

Maine would revisit the concept of Timeslip (and ‘Time Slip’, its television precursor) in his 1957 novel The Isotope Man. The novel follows the film’s narrative quite closely. Maine would write two sequels to the novel, all following the adventures of Delaney. The original UK release ran for 93:15 mins (and is listed in the BBFC database as ‘Time Slip’; the original script suggests the film’s title should be ‘Timeslip’, which is as it is presented on this DVD release from Network). This DVD runs for 90:08 minutes, in PAL format, which suggests that the film is intact. (Certainly, it has never suffered any cuts under the BBFC. However, in the US, where it was released as The Atomic Man, the film was cut down to approximately 77 minutes for its cinema release.)

Video

Shot on 35mm and in monochrome, Timeslip is presented here in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1, with anamorphic enhancement. This aspect ratio seems perfectly fine and is most likely the intended aspect ratio. The opening scene, set on the banks of the Thames at night-time, exhibits some crushed blacks. This is a characteristic of the low-light scenes throughout the film. The film has a soft appearance on the whole: it’s not terrible but it’s not great either. The source print is quite clean, but there are some vertical scratches (notoriously difficult to remove) and debris throughout the picture – nothing too detrimental, however. It’s a reasonably good presentation of the film, probably the best that can be expected given the relative obscurity of the picture.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track. This is fine and clear throughout. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes the film’s trailer (2:13) and a stills gallery (1:10). Also included is the original script (as a .PDF file).

Overall

Timeslip is an entertaining crime picture with some comic interludes. (It’s probably these that were omitted from the abbreviated US version of the film.) The leads are engaging and there is some sparkling dialogue. The presentation of the film on this disc is good but not great – probably the best we’re likely to see, however, given the film’s relative obscurity. Fans of British attempts to emulate the style and approach of American films noirs will find this a worthwhile purchase. Timeslip is an entertaining crime picture with some comic interludes. (It’s probably these that were omitted from the abbreviated US version of the film.) The leads are engaging and there is some sparkling dialogue. The presentation of the film on this disc is good but not great – probably the best we’re likely to see, however, given the film’s relative obscurity. Fans of British attempts to emulate the style and approach of American films noirs will find this a worthwhile purchase.

This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|