|

|

Rabid AKA Rage (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th February 2015). |

|

The Film

Rabid (David Cronenberg, 1977) Rabid (David Cronenberg, 1977)

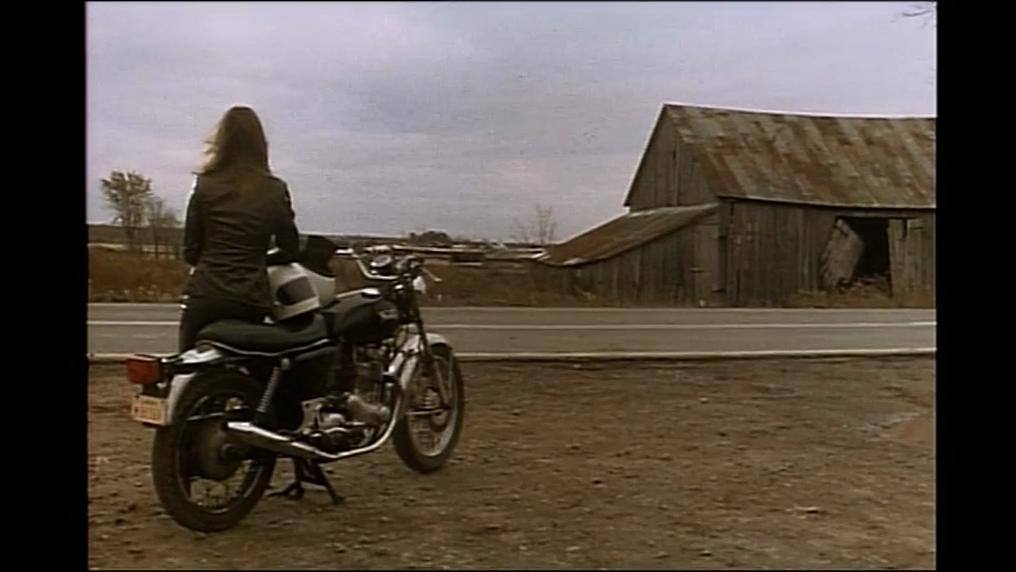

Given the go-ahead after the financial success of Cronenberg’s previous picture Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977) was again financed by Cinépix and the Canadian Film Development Corporation, at a time when Cinépix was shifting its focus towards thrillers and horror films, and away from the soft-core pictures (‘maple syrup porn’) that had been its bread and butter since the late-1960s. On Rabid, Cronenberg again worked with producer Ivan Reitman and special effects supervisor Joe Blasco, along with a number of the same cast members, and although Cronenberg reputedly requested Sissy Spacek, the film’s lead role was given to Marilyn Chambers, the star of the Mitchell Brothers’ Behind the Green Door (1973). The origins of Rabid were in a script that was originally entitled ‘Mosquito’ and which was an attempt to depict ‘a strange kind of modern-day vampire, a biologically-correct vampire’ that sidestepped the usual representation of vampires as produces of supernatural forces (Cronenberg, quoted in Rodley, 1992: 53). Within the film, vampirism is shown to be the byproduct of a radical skin graft technique developed by the Keloid Clinic. The film opens at the Keloid Clinic, where business partners Murray Cypher (Joe Silver) and Dan Keloid (Howard Ryshpan) discuss the future of the business: Murray wants to attract big investors to push their plastic surgery business into franchised operations, whilst Dan fears the commercialisation of their work, which is at the cutting edge (pun intended) of the profession. Meanwhile, nearby, Hart (Frank Moore) and his girlfriend Rose (Chambers) are involved in a motorcycle accident, and the pair are brought by ambulance to the Keloid Clinic. Dan proposes using a radical new skin graft technique to aid Rose’s recovery, treating the grafts ‘so that they become morphogenically neutral’ and applying them to the damaged tissue as ‘neutral field grafts’. As Dan explains, ‘In other words, neutral field tissue has the same ability to form any part of the human body that the tissue of a human embryo has’.  Over time, Hart recovers and returns to Montreal. However, Rose remains at the clinic in a coma; during this period, Dan notes that the internal grafts are showing a ‘definite sign of new tissue growth happening in the abdominal cavity’. Eventually, Rose awakens from her coma, screaming. She is comforted by another patient, Lloyd (Roger Periard); but as he embraces her, Rose breathes heavily, almost orgasmically, as a new penis-like growth with a sharp tip extends from a vagina-like opening in her armpit and penetrates Lloyd’s flesh, allowing the transference of his blood to Rose. Lloyd is discovered; his wound refuses to clot. Rose appears to still be comatose. The first assumption is that he has tried to sexually assault Rose whilst she is in her coma. This allows Rose to escape from the clinic at night. Stumbling onto a nearby farm, she embraces a cow and drains it of blood before she is interrupted by a drunken farmer, who immediately becomes Rose’s next victim. Over time, Hart recovers and returns to Montreal. However, Rose remains at the clinic in a coma; during this period, Dan notes that the internal grafts are showing a ‘definite sign of new tissue growth happening in the abdominal cavity’. Eventually, Rose awakens from her coma, screaming. She is comforted by another patient, Lloyd (Roger Periard); but as he embraces her, Rose breathes heavily, almost orgasmically, as a new penis-like growth with a sharp tip extends from a vagina-like opening in her armpit and penetrates Lloyd’s flesh, allowing the transference of his blood to Rose. Lloyd is discovered; his wound refuses to clot. Rose appears to still be comatose. The first assumption is that he has tried to sexually assault Rose whilst she is in her coma. This allows Rose to escape from the clinic at night. Stumbling onto a nearby farm, she embraces a cow and drains it of blood before she is interrupted by a drunken farmer, who immediately becomes Rose’s next victim.

Rose returns to the clinic. It soon becomes apparent that her previous victims are, after an incubation period of six to eight hours, exhibiting the symptoms of rabies and attacking other people, displaying a cannibalistic appetite for human flesh (‘I gotta eat! I gotta eat!’ the drunk moans whilst attacking the waitress at a roadside diner) and spreading the infection even further. Meanwhile, at the clinic Rose is comforted by Dan and, after he discovers the opening in her armpit, attacks him. She escapes from the clinic again, leaving a trail of destruction in her wake as she hitch-hikes to Montreal; news broadcasts speak of an ‘outbreak of a new strain of rabies’. In Montreal, the disease spreads even further, and martial law is enacted. Refuse trucks are sent onto the streets of the city, manned by armed troops in white suits and masks: their intention is to kill the infected and clear the streets of their bodies. Apparently driven by instinct, Rose prowls the streets in the search for more victims but eventually develops an awareness of what is happening to (and through) her, begging Hart to help her.  Ernest Mathijs has suggested that both Shivers and Rabid follow on from ‘where [Cronenberg’s short features] Stereo [1969] and Crimes of the Future [1970] left off’, in the sense that both pictures ‘consider the body as a site of revolution, awash with lustful, vampiric desires to suck blood and infect insanity upon innocents, and countered by attempts to rein it by totalitarian systems of control’ (Mathijs, 2008: 30). One of the attractions of Rabid for Cronenberg was the possibility that the project offered of showing similar events to those depicted in Shivers but on a larger scale, ‘showing an entire city in thrall to rabid maniacs: army trucks, martial law in Montreal and so on’ (Cronenberg, quoted in Rodley, 1992: 53). The depiction of the infected within the film has much in common with George Romero’s reworking of the zombie (as mindless flesh-eating cadaver, rather than as the more traditional voodoo slave) in Night of the Living Dead (1968): Laura Helen Marks has suggested that both Rabid and Shivers ‘depict a mass infection that produces zombie-like characteristics in humans and is connected to sexuality. The infected are deprived of free will’ (2014: 60). Like Romero’s zombie films, Rabid and Shivers ‘are apocalyptic in vision and urban in setting. They end with no solution in sight’ (ibid.). However, unlike Shivers, Rabid depicts the ‘medically sourced plague that turns people from normal citizens into ravening monsters’ in an unambiguously ugly way: whereas in Shivers, the victims of the parasite within Starliner Towers show no outward signs of being infected (other than their uncontrolled id), in Rabid those infected by Rose (or those who have been infected by the infected) display ‘ugly’ symptoms’, including ‘rheumy eyes and puffy yellowish complexion, green froth foaming from the mouth, and […] a gleeful and vicious appetite for flesh’ (Beard, 2001: 49). Ernest Mathijs has suggested that both Shivers and Rabid follow on from ‘where [Cronenberg’s short features] Stereo [1969] and Crimes of the Future [1970] left off’, in the sense that both pictures ‘consider the body as a site of revolution, awash with lustful, vampiric desires to suck blood and infect insanity upon innocents, and countered by attempts to rein it by totalitarian systems of control’ (Mathijs, 2008: 30). One of the attractions of Rabid for Cronenberg was the possibility that the project offered of showing similar events to those depicted in Shivers but on a larger scale, ‘showing an entire city in thrall to rabid maniacs: army trucks, martial law in Montreal and so on’ (Cronenberg, quoted in Rodley, 1992: 53). The depiction of the infected within the film has much in common with George Romero’s reworking of the zombie (as mindless flesh-eating cadaver, rather than as the more traditional voodoo slave) in Night of the Living Dead (1968): Laura Helen Marks has suggested that both Rabid and Shivers ‘depict a mass infection that produces zombie-like characteristics in humans and is connected to sexuality. The infected are deprived of free will’ (2014: 60). Like Romero’s zombie films, Rabid and Shivers ‘are apocalyptic in vision and urban in setting. They end with no solution in sight’ (ibid.). However, unlike Shivers, Rabid depicts the ‘medically sourced plague that turns people from normal citizens into ravening monsters’ in an unambiguously ugly way: whereas in Shivers, the victims of the parasite within Starliner Towers show no outward signs of being infected (other than their uncontrolled id), in Rabid those infected by Rose (or those who have been infected by the infected) display ‘ugly’ symptoms’, including ‘rheumy eyes and puffy yellowish complexion, green froth foaming from the mouth, and […] a gleeful and vicious appetite for flesh’ (Beard, 2001: 49).

Citing Murray Smith, Justin D Edwards and Rune Graulund suggest that in Shivers, Cronenberg refuses to represent the occupants of Starliner Towers ‘as victims; instead, he invokes the perspective of the inhuman […] by dispelling the audience’s sympathy for the targets of the parasite’ (Smith, cited in Edwards & Graulund, 2013: 58). The result of this is a ‘distancing’ and ‘defamiliarisation’ of the human body (ibid.). In Rabid, Cronenberg achieves something similar with the ‘victims’ of Rose’s need for blood, a number of whom (the lecherous drunk who accosts Rose in a barn; the equally lecherous man who hits on Rose when she visits a seedy porno cinema in the search for victims) are shown to be predatory before their encounter with Rose. Certainly, after they have been attacked by Rose (or by another of Rose’s victims), they are depicted as inhuman, mindless, snarling beasts, similar in many ways to the flesh-eating zombies that populate Romero’s Night of the Living Dead or the infected victims of the Trixie virus in Romero’s The Crazies (1973). In a news broadcast that invites direct comparison with the television broadcasts (‘If you have a gun, shoot 'em in the head [.…] If you don't, get yourself a club or a torch. Beat 'em or burn 'em. They go up pretty easy’) in Night of the Living Dead – and the later Dawn of the Dead (1978) – during one televised discussion in Rabid, an interviewee asserts that ‘The victims of the disease are beyond medical help, once it has established itself to the degree of inducing violent behaviour [….] What I’m saying is very simple and it may not be very palatable for your viewers. Shooting down the victims is as good a way of handling them as we have got. If we lock them up, they eventually go into a coma and die shortly afterwards’. Edwards and Graunlund argue that in Rabid, Cronenberg divides the characters into three types, ‘all of whom are victims of different forms of terror’: ‘the d/evolved vampire [Rose], the walking un/dead [her victims] and the unbitten human’ (ibid.: 59). Despite its attempts to disanchor vampirism from the realm of the supernatural, the film’s depiction of vampirism, Edwards and Graunlund argue, is ‘true to folkloric tradition’ in its focus on a vampire who ‘comes back from the dead not to renew or reanimate life, but to suck the life out of others and spread, at first unknowingly, the animalistic illness of a new strain of rabies’ – much like the arrival in Bremen of Count Orlok (Max Schreck) in F W Murnau’s 1922 Nosferatu (the title of which is derived from the Old Slavonic word ‘nosufuratu’: ‘plague-carrier’) heralds the appearance of a plague.  Rabid is emblematic of the ‘body horror’ films of the 1970s, ‘incorporat[ing] the popularity of representations of vampires and zombies’ whilst also ‘represent[ing] a series of grotesque bodies that are marked by decomposition, decay and disgust’ (Edwards & Graunlund, 2013: 59). Where some of Cronenberg’s body horror pictures (Shivers, The Brood and Scanners) focus on the ‘liberation of mental and psychic forces in ways that transform bodies’, Rabid is the first of another group of pictures within Cronenberg’s career (including The Fly, 1986; Videodrome, 1982; Dead Ringers, 1988; and eXistenZ, 1999) that ‘suggest a causal link between experiments with technology and the mutation of the body’ (Humphries, 2002: 169). Where in The Brood (1979), for example, inner emotions (principally, rage) are shown to have physical (‘psychoplasmic’) manifestations, in Rabid it is Dr Keloid’s experimental skin grafts that produce the blood-sucking parasite that resides within Rose: like The Fly and eXistenZ, in Rabid experimental technology results in a mutation of the human body. However, in both of these groups of films, Reynold Humphries argues, the human ‘body is transformed […] into an object over which the subject has no control’: in The Fly, for example, ‘Brundlefly’ is unable to control his body’s degeneration (ibid.). Likewise, in Rabid Rose is an unwitting participant in her evolution into a ‘vampire’. She has moments of lucidity – telephoning Hart and begging him for help and, ultimately, locking herself in a room with one of her own rabid victims – that highlight her cognisance of what is happening to her body and her concomitant desire to stop it, something which can only be achieved by her own destruction. Humphries argues that these films, in their focus on the individual’s loss of control over their own lives, function ‘as a metaphor for the worker or small businessman, scientist or intellectual, the fruits of whose labour are stolen from him as he assists helplessly, as if an outsider, while simultaneously misrecognising his real subject status’ (ibid.). Ironically, the film opens with Dan and Murray discussing the future of the Keloid Clinic, Murray suggesting that they expand their plastic surgery business into franchised operations with a big backer, and Dan arguing that ‘I sure as hell don’t want to become the Colonel Sanders of plastic surgery’. Rabid is emblematic of the ‘body horror’ films of the 1970s, ‘incorporat[ing] the popularity of representations of vampires and zombies’ whilst also ‘represent[ing] a series of grotesque bodies that are marked by decomposition, decay and disgust’ (Edwards & Graunlund, 2013: 59). Where some of Cronenberg’s body horror pictures (Shivers, The Brood and Scanners) focus on the ‘liberation of mental and psychic forces in ways that transform bodies’, Rabid is the first of another group of pictures within Cronenberg’s career (including The Fly, 1986; Videodrome, 1982; Dead Ringers, 1988; and eXistenZ, 1999) that ‘suggest a causal link between experiments with technology and the mutation of the body’ (Humphries, 2002: 169). Where in The Brood (1979), for example, inner emotions (principally, rage) are shown to have physical (‘psychoplasmic’) manifestations, in Rabid it is Dr Keloid’s experimental skin grafts that produce the blood-sucking parasite that resides within Rose: like The Fly and eXistenZ, in Rabid experimental technology results in a mutation of the human body. However, in both of these groups of films, Reynold Humphries argues, the human ‘body is transformed […] into an object over which the subject has no control’: in The Fly, for example, ‘Brundlefly’ is unable to control his body’s degeneration (ibid.). Likewise, in Rabid Rose is an unwitting participant in her evolution into a ‘vampire’. She has moments of lucidity – telephoning Hart and begging him for help and, ultimately, locking herself in a room with one of her own rabid victims – that highlight her cognisance of what is happening to her body and her concomitant desire to stop it, something which can only be achieved by her own destruction. Humphries argues that these films, in their focus on the individual’s loss of control over their own lives, function ‘as a metaphor for the worker or small businessman, scientist or intellectual, the fruits of whose labour are stolen from him as he assists helplessly, as if an outsider, while simultaneously misrecognising his real subject status’ (ibid.). Ironically, the film opens with Dan and Murray discussing the future of the Keloid Clinic, Murray suggesting that they expand their plastic surgery business into franchised operations with a big backer, and Dan arguing that ‘I sure as hell don’t want to become the Colonel Sanders of plastic surgery’.

As in Shivers, in Rabid the ‘field of action spreads from the confines of a self-contained institution’: in the case of Shivers, Starliner Towers; in the case of Rabid, the Keloid Clinic (Beard, op cit.: 49). Like Starliner Towers in Shivers or the ConSec building in Scanners (1981), the Keloid Clinic is ‘an example of bucolic architecture set in almost bucolic surroundings, with laws and trees […] a symbol of wealth cut off from the outside world’ (Humphries, op cit.: 169). The first shot of the Keloid Clinic shows ‘an ultra-modern block whose windows, which cover most of its surface, repel any attempt to see in and only reflect the trees standing outside’ (ibid.). The climax of Shivers ends with the infected inhabitants of Starliner Towers leaving the luxury apartment complex in their cars, heading for Montreal, just before dawn breaks; as this happens, a radio broadcast heard on the film’s soundtrack notes that a series of unexplained sexual assaults have taken place across Montreal, suggesting that the parasite has spread beyond the grounds of the institution in which it was produced. With a good portion of its narrative focusing on the explosion of violence in Montreal as the disease spread by Rose intensifies in its scope, William Beard suggests that Rabid may be seen as ‘a continuation of [the narrative] of Shivers: here is what happens when the plague gets to Montreal’ (ibid.). As in Shivers, in Rabid the ‘field of action spreads from the confines of a self-contained institution’: in the case of Shivers, Starliner Towers; in the case of Rabid, the Keloid Clinic (Beard, op cit.: 49). Like Starliner Towers in Shivers or the ConSec building in Scanners (1981), the Keloid Clinic is ‘an example of bucolic architecture set in almost bucolic surroundings, with laws and trees […] a symbol of wealth cut off from the outside world’ (Humphries, op cit.: 169). The first shot of the Keloid Clinic shows ‘an ultra-modern block whose windows, which cover most of its surface, repel any attempt to see in and only reflect the trees standing outside’ (ibid.). The climax of Shivers ends with the infected inhabitants of Starliner Towers leaving the luxury apartment complex in their cars, heading for Montreal, just before dawn breaks; as this happens, a radio broadcast heard on the film’s soundtrack notes that a series of unexplained sexual assaults have taken place across Montreal, suggesting that the parasite has spread beyond the grounds of the institution in which it was produced. With a good portion of its narrative focusing on the explosion of violence in Montreal as the disease spread by Rose intensifies in its scope, William Beard suggests that Rabid may be seen as ‘a continuation of [the narrative] of Shivers: here is what happens when the plague gets to Montreal’ (ibid.).

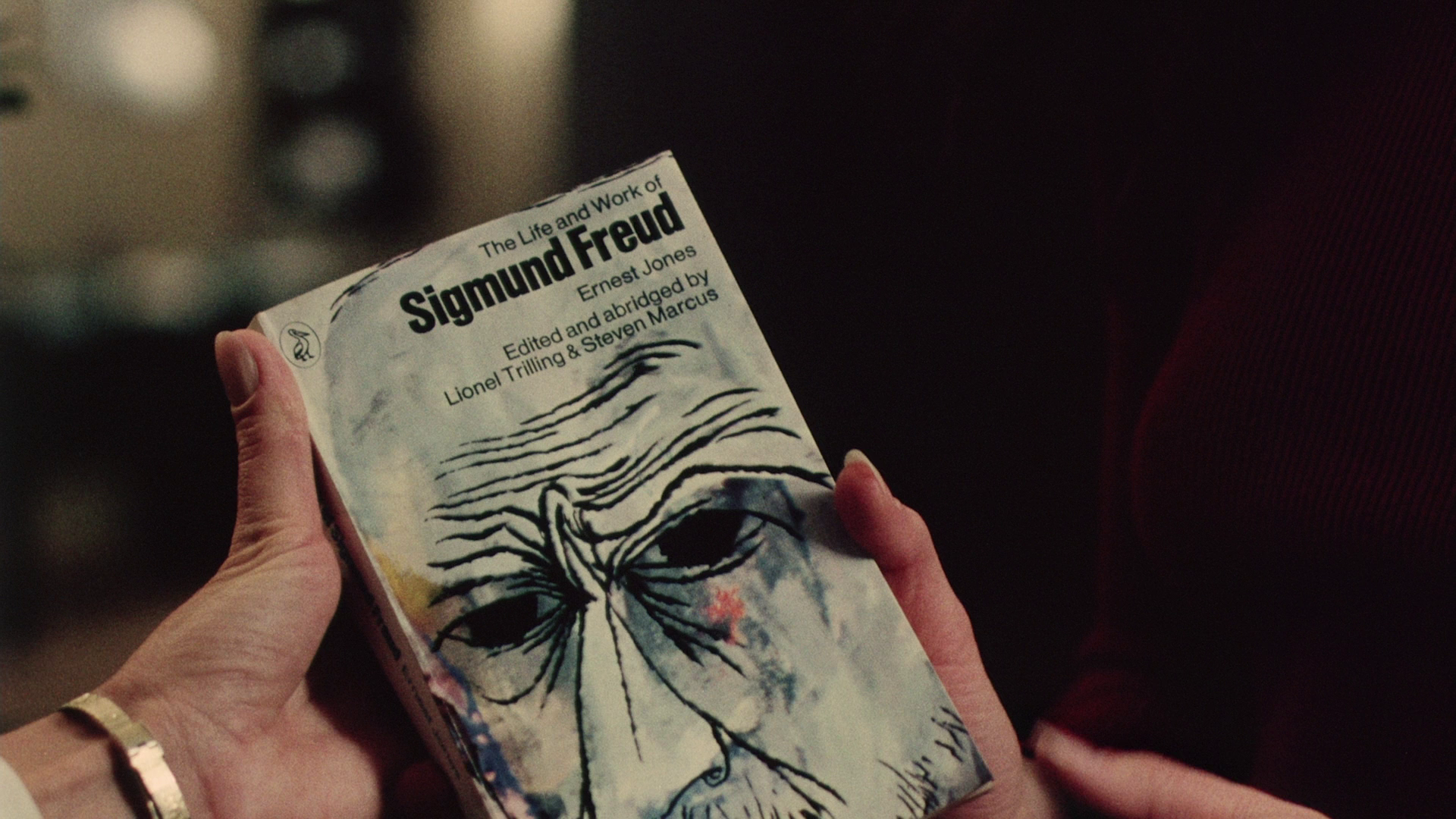

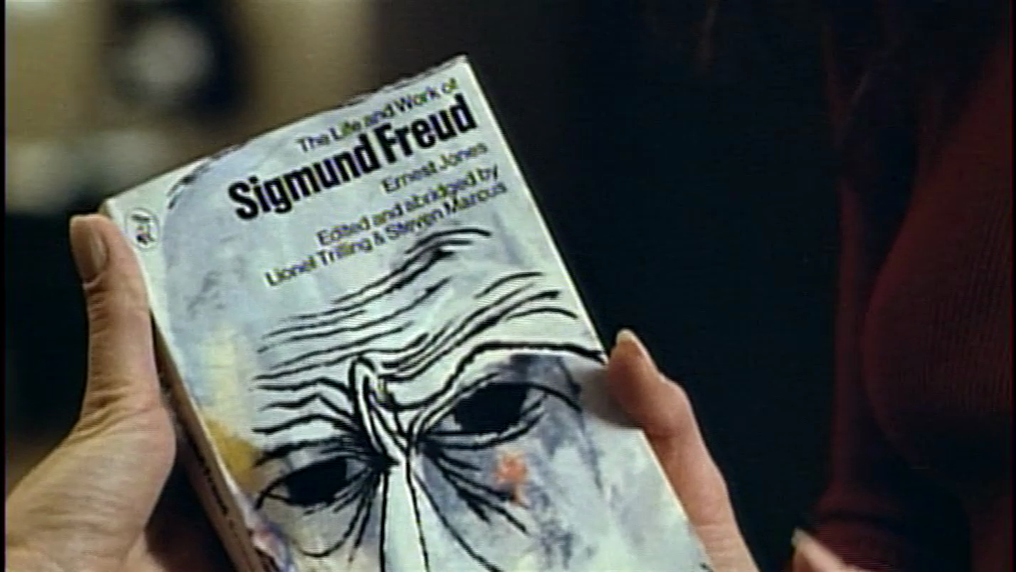

In some ways, given Marilyn Chambers’ status as the star of the Mitchell Brothers’ Behind the Green Door (1972), Linda S Kaufman argues that Rabid may be seen as a picture ‘about the commodification of sex’, offering a ‘parable of the porno queen’s revenge’ (Kaufman, 1998: 123). Chambers’ appearance in the film has been seen as an attempt by the actress at achieving a more mainstream role, but as William Beard argues since Chambers ‘is always-already a presence of sexual transgression, Rose takes on this quality as well – and it is allied immediately with raging aggressive appetite and spectacular disease and destruction in a way paralleling the same cluster of associations in Shivers’ (Beard, op cit.: 51). A number of sequences within the film exploit and subvert Chambers’ history as a porn actress: ‘far from passively acquiescing to men’s looks, [Rose] is an active “looker,” cruising the malls and boulevards’ in her search for victims (Kaufman, op cit.: 123). As Kaufman observes, all of Rose’s victims ‘have the kinds of stereotypical macho roles that one finds in porno magazines: a farmer, truck driver, doctor, and suave playboy all bite the dust when she bites them’ (ibid.). During one sequence, Rose visits a porno theatre where she is approached by a man who, once he has seated himself next to her, succumbs to her deadly embrace and becomes one of her victims; in another sequence, she visits a shopping mall where a young man makes advances to her, but before Rose can exploit his attentions towards her, the equilibrium within the mall is disrupted by one of the infected, leading to an outbreak of violence during which an overeager young police officer armed with a machine gun shoots both the infected attacker and the mall’s innocent Santa Claus. Beard argues that there is a dualism at play within Chambers’ performance as Rose: within the film’s narrative, Rose is ‘basically innocent and suffering and humanly sympathetic’, but ‘[s]upra-diegetically, Marilyn Chambers is creating havoc with her horrifically powered sexuality’ (Beard, op cit.: 52).  In the early sequences, Cronenberg happily satirises the work of the Keloid Clinic and its clientele. When the badly injured Rose is rushed into the Keloic Clinic on a gurney, one of the private clients wrinkles his nose in disgust and complains, ‘You’d think they could cover it with a sheet or something’. Later, a new client, Judy Glasberg (Terry Schlonblum), enters the clinic for a new nose job at the behest of her father, who has told her that her previous nose job has left her with a nose that is too similar to his. As she enters the clinic, Judy is carrying a book about Freud: ‘I’m terrified to find out what it [her father’s demand that she have yet another nose job] really means’, she jokes. The experimental surgery that Dan performs on Rose is, he admits (in a wonderful example of litotes), ‘a little out of the ordinary’: it is an experimental method that is applied to compensate for the lack of ‘heavy medical hardware’. The medical hubris behind Dan’s procedure, and the ethos of the Keloid Clinic as a whole, is underscored later when Rose, in a moment of clarity after she has awoken from her coma and already infected Lloyd and the drunken farmer, tells Dan, ‘I’m hideous, doctor. I’m crazy. I’m a monster’. Dan’s response is to tell her, simply and without any sense of irony, ‘There’s just about nothing we can’t fix, if we know what’s wrong’. In the early sequences, Cronenberg happily satirises the work of the Keloid Clinic and its clientele. When the badly injured Rose is rushed into the Keloic Clinic on a gurney, one of the private clients wrinkles his nose in disgust and complains, ‘You’d think they could cover it with a sheet or something’. Later, a new client, Judy Glasberg (Terry Schlonblum), enters the clinic for a new nose job at the behest of her father, who has told her that her previous nose job has left her with a nose that is too similar to his. As she enters the clinic, Judy is carrying a book about Freud: ‘I’m terrified to find out what it [her father’s demand that she have yet another nose job] really means’, she jokes. The experimental surgery that Dan performs on Rose is, he admits (in a wonderful example of litotes), ‘a little out of the ordinary’: it is an experimental method that is applied to compensate for the lack of ‘heavy medical hardware’. The medical hubris behind Dan’s procedure, and the ethos of the Keloid Clinic as a whole, is underscored later when Rose, in a moment of clarity after she has awoken from her coma and already infected Lloyd and the drunken farmer, tells Dan, ‘I’m hideous, doctor. I’m crazy. I’m a monster’. Dan’s response is to tell her, simply and without any sense of irony, ‘There’s just about nothing we can’t fix, if we know what’s wrong’.

The film was shot only a handful of years after the ‘October Crisis’ and the FLQ’s (Front de libération du Québec) campaign of terrorism, which had the aim of establishing sovereignty for Quebec and which included the 1969 bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange and, in 1970, the murder of Quebec’s deputy premiere Pierre Laporte and kidnapping of British diplomat James Cross. The FLQ’s activities led to the implementation of the War Measures Act, which resulted in armed troops on the streets of Montreal, an event which Cronenberg has cited as ‘traumatizing for Canadians who are not used to seeing guns on the streets in any form’ (quoted in Edwards, 2013: 71). Cronenberg has suggested that ‘the similarities were striking’ between the iconography of this period and the climax of Rabid, which depicts troops riding refuse lorries shooting the infected and then collecting their bodies. In one sequence, as Hart drives through Montreal his car is attacked by a member of the infected. A soldier kills the man who is laying siege to the car Hart is driving before nonchalantly cleaning Hart’s windscreen, as if providing him with a service, and allowing Hart to drive away. Not a word is spoken. Some previous DVD releases (and Arrow’s own VHS release from many years ago) omitted a small amount of footage as Murray and Hart leave a police station after being vaccinated against the disease during the epidemic and are advised by an officer to ‘Remember to keep your windows up and your doors locked once you get into the city. Maybe the bug can’t get you now, but that shot won’t protect you from the crazies’. Other DVD releases trimmed a shot of a train arriving in a station. This Blu-ray release from Arrow is intact, containing all of this footage. The film runs for 91:20 mins. (In the interests of full disclosure, I’m listed in the ‘Special Thanks’ in the booklet of this release for providing Arrow with this information regarding the footage missing from previous home video releases.)

Video

The presentation of the film, which takes up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, which is near-as dammit to the original aspect ratio. Compared with the previous UK DVD release from Metrodome, in this presentation the compositions are opened up on all four sides considerably. (Some screen grabs comparing this Blu-ray release with the previous Metrodome UK DVD release of the film are available at the bottom of this page.) The presentation of the film, which takes up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, which is near-as dammit to the original aspect ratio. Compared with the previous UK DVD release from Metrodome, in this presentation the compositions are opened up on all four sides considerably. (Some screen grabs comparing this Blu-ray release with the previous Metrodome UK DVD release of the film are available at the bottom of this page.)

In comparison with previous DVD releases, Arrow’s Blu-ray has a slightly different hue, which looks almost identical to the effect that’s achieved when film intended for exposure in daylight is used under tungsten lights (resulting in the whites being pushed towards yellow), and stronger contrast – which may or may not be more true to the film’s original ‘look’, considering the issues the DVD format had in its early years in capturing filmic contrast. It’s certainly not a naturalistic film, so the hegemony of white light doesn’t necessarily apply here. (For an interesting point of comparison, Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction was reputedly shot entirely on daylight film, even for its interior sequences, and the interiors in that film have a similar hue to the interior sequences in this presentation of Rabid.) The stronger contrast in this presentation certainly gives some of the sequences a more expressionistic aesthetic: for example, in the sequence during which Rose visits a porno theatre, and the faces of the patrons are buried in shadow, halos of light surrounding them, whilst her face is lit clearly; or the sequence in which Rose descends a staircase, the light filtering through the banister and the shadows cast by this suggesting her entrapment within a cage (see the two relevant screen grabs at the bottom of this review). Exterior sequences capture the harsh coldness of winter light (as can be seen in the screen grabs, again at the bottom of this review, of Hart and Murray in Murray's car, and Rose standing by the roadside). As exhibited in the large screen grabs at the bottom of this review, there’s an impressive level of detail on display here, and the film exhibits a natural level of film grain which is resolved well within the encode.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless LPCM mono track. This is clean and audible throughout – not a ‘flashy’ track, by any means, but evidencing good range where it’s needed. Also included is an isolated music and effects track (LPCM mono). Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes two audio commentaries, one by director David Cronenberg and another by critic William Beard. Cronenberg discusses the origins of the film and its production, elaborating on the film’s themes; Beard’s commentary situates the film within the context of Cronenberg’s career as a filmmaker, exploring its relationship with the Canadian film industry and offering a more objective analysis of some of the ideas within Rabid. The disc includes two audio commentaries, one by director David Cronenberg and another by critic William Beard. Cronenberg discusses the origins of the film and its production, elaborating on the film’s themes; Beard’s commentary situates the film within the context of Cronenberg’s career as a filmmaker, exploring its relationship with the Canadian film industry and offering a more objective analysis of some of the ideas within Rabid.

A series of interviews are included: - David Cronenberg (20:35). Cronenberg reflects on Rabid’s production and reception, and in particular Robert Fulford’s article criticising Shivers and the fact that it had been financed, partly, by the Canadian taxpayer. - Ivan Reitman (12:28). Reitman talks about working for Cinépix and discusses the production of both Rabid and Shivers. - Don Carmody (15:36). Carmody, the film’s co-producer, also discusses his relationship with Cinépix and his work on both Rabid and Shivers. - Joe Blasco (3:11). Blasco discusses his special effects work for Rabid. Two documentaries: - ‘The Directors: The Films of David Cronenberg’ (59:04). Produced in 1999, around the time of the release of eXistenZ, this documentary takes a look at Cronenberg’s career to that point. It features some illuminating comments from Cronenberg himself and many of the people he has worked with (such as Michael Ironside, Peter Weller and Deborah Harry). It’s cropped up as an extra on previous DVD releases of Cronenberg’s films but is worth watching again. - ‘Raw, Rough and Rabid’ (15:04). This newly-produced featurette features comments by Canadian critic Kier-La Janisse and Joe Blasco, offering discussion of the role of Cinépix within the Canadian film industry. The disc also includes the film’s trailer (2:09) and a gallery of promotional artwork.

Overall

Rabid is an unsettling film which offers no easy solutions to the questions it raises: the narrative posits the barbaric behaviour of the infected against a trigger-happy system of repression, and ultimately nobody wins. It’s a thoroughly unsentimental film: in what is arguably the picture’s most nightmarish sequence, Murray Cypher returns home to Montreal after visiting the Keloid Clinic with Hart, following Rose’s escape and Dan’s outburst of violence in the operating room, and discovers that his wife has killed and devoured their baby, with whom Murray had previously been seen in a happy parental embrace (the imagery of which lingers in the mind when Murray discovers blood in the baby’s bathwater and realises what has happened to the child). However, the film also has a deep streak of black humour. For example, in one sequence, whilst travelling in a City of Montreal car, health official Claude LaPointe (Victor Désy) complains about the city’s slow response to the attacks, asserting that ‘I think the mayor should be taking this epidemic a little more seriously’. In answer to this statement, he is told by Maclaren, a city official, that ‘The city’s a complex machine, Mr LaPointe. It needs constant attention [….] It takes time’. The car in which they are travelling is brought to a halt: the road is blocked by city workers. Maclaren’s first thought is that ‘it may be strike trouble’, but the workers quickly reveal themselves to be infected and attack the vehicle with their tools, dragging the occupants out of the car and feasting upon them. Rabid is an unsettling film which offers no easy solutions to the questions it raises: the narrative posits the barbaric behaviour of the infected against a trigger-happy system of repression, and ultimately nobody wins. It’s a thoroughly unsentimental film: in what is arguably the picture’s most nightmarish sequence, Murray Cypher returns home to Montreal after visiting the Keloid Clinic with Hart, following Rose’s escape and Dan’s outburst of violence in the operating room, and discovers that his wife has killed and devoured their baby, with whom Murray had previously been seen in a happy parental embrace (the imagery of which lingers in the mind when Murray discovers blood in the baby’s bathwater and realises what has happened to the child). However, the film also has a deep streak of black humour. For example, in one sequence, whilst travelling in a City of Montreal car, health official Claude LaPointe (Victor Désy) complains about the city’s slow response to the attacks, asserting that ‘I think the mayor should be taking this epidemic a little more seriously’. In answer to this statement, he is told by Maclaren, a city official, that ‘The city’s a complex machine, Mr LaPointe. It needs constant attention [….] It takes time’. The car in which they are travelling is brought to a halt: the road is blocked by city workers. Maclaren’s first thought is that ‘it may be strike trouble’, but the workers quickly reveal themselves to be infected and attack the vehicle with their tools, dragging the occupants out of the car and feasting upon them.

William Beard has suggested that one of the elements of Cronenberg’s ‘monster’ movies (including Rabid, The Fly and Scanners) that separates them from the majority of such pictures is the fact that Cronenberg’s monster pictures ‘present something other than a spectacle of desire or horror, and in particular present an empathic perspective of human sadness and suffering’ (Beard, op cit.: 52). When Rose returns to her apartment in Montreal, she is shown writhing about on the floor of her bathroom, like a junkie going through withdrawal; at times, her behaviour exhibits her awareness of what is taking place, and the disaster she has caused, but she seems unable to control what is happening to her. Rabid is in many ways a companion piece to Shivers, exploring similar themes; but whereas the climax of Shivers shows the infection spreading beyond the confines of Starliner Towers, the resolution of Rabid shows the infection apparently in the process of being stopped by a repressive, trigger-happy system of authority, the corpses of the infected being inhumanly thrown into the compactors of refuse trucks. The presentation of the film on this disc is impressive: in comparison with previous DVD releases, it seems balanced for a different colour temperature, but this may or may not be closer to the film’s original aesthetic (the DVDs can hardly be used as a benchmark for how the film 'should' look). The stronger contrast on this Blu-ray certainly seems more filmic and expressive because of this, and combined with the increased level of detail this ensures that the Blu-ray offers a very handsome way to view Rabid. The contextual material is superb too. This is a very impressive release of a film that has had a number of unsatisfying DVD releases, a good number of which were missing some footage which is thankfully intact here. Given the preponderance of body horror-themed films over the past twenty or thirty years, it’s sometimes easy to forget how revolutionary Cronenberg’s early films were; Arrow’s new release of Rabid offers a perfect opportunity to remind us of this film’s potency.  References: Beard, William, 2001: David Cronenberg: The Artist as Monster. University of Toronto Press Beaty, Bart, 2008: David Cronenberg’s ‘A History of Violence’. University of Toronto Press Edwards, Justin D, 2013: ‘Canada, Quebec and David Cronenberg’s Terrorist-Vampires’. In: Khair, Tabish & Hoglund, Johan (eds), 2013: Transnational and Postcolonial Vampires. : 67-80 Edwards, Justin D & Graulund, Rune, 2013: Grotesque: The New Critical Idiom. London: Routledge Humphries, Reynold, 2002: The American Horror Film: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press Kaufman, Linda S, 1998: Bad Girls and Sick Boys: Fantasies in Contemporary Art and Culture. University of California Press Marks, Laura Helen, 2014: ‘David Cronenberg’. In: Pulliam, June Michele & Fonseca, Anthony J (eds), 2014: Encyclopedia of the Zombie: The Walking Dead in Popular Culture and Myth. California: ABC-CLIO: 59-61 Mathijs, Ernest, 2008: The Cinema of David Cronenberg: From Baron of Blood to Cultural Hero. London: Wallflower Press Rodley, Chris, 1992: Cronenberg on Cronenberg. London: Faber & Faber Visual comparison with the Metrodome DVD previously released in the UK. Arrow’s Blu-ray:

Metrodome’s DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

Metrodome’s DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

Metrodome’s DVD:

Arrow’s Blu-ray:

Metrodome’s DVD:

Additional screen grabs from Arrow’s Blu-ray release:

|

|||||

|