|

|

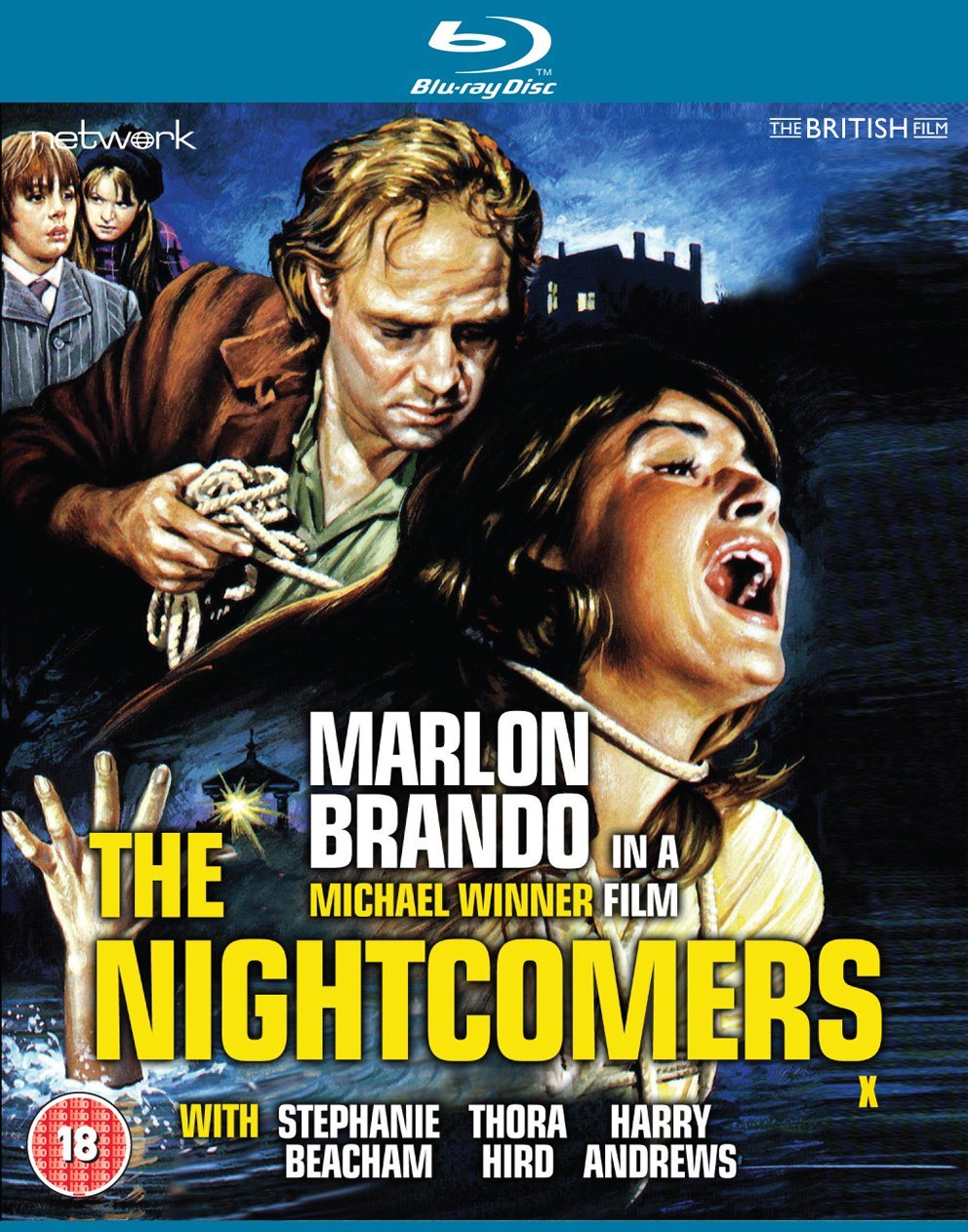

Nightcomers (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st March 2015). |

|

The Film

The Nightcomers (Michael Winner, 1971) The Nightcomers (Michael Winner, 1971)

Following the deaths of their parents in a road accident in France, young Miles (Christopher Ellis) and Flora (Verna Harvey) are faced with the disinterest of their new guardian, their uncle (Harry Andrews). After quickly settling the affairs of Miles and Flora’s parents, the uncle leaves Miles and Flora in their family home, Bly House, in the care of their governess Miss Jessel (Stephanie Beacham), housekeeper Mrs Grose (Thora Hird) and valet Peter Quint (Marlon Brando). Whilst Miss Jessel takes care of the children’s education, much of their spare time is spent with Quint, who plays with the children but also shares his materialist and devoutly adult worldview with them, telling them matter-of-factly that death is the end of existence (‘The dead go nowhere because they’ve got nowhere to go, see. There’s no heaven or hell or that nonsense’) and that sometimes, love and hate are interchangeable. Quint’s refusal to sugarcoat existence for the sake of the children leads to them becoming confused; and this sense of moral turpitude is exacerbated when Miles and Flora witness, and then re-enact, the unknowing Quint and Miss Jessel’s sadomasochistic lovemaking. Prior to the 1970s, Michael Winner’s career as a director oscillated between outrageous comedies such as Play it Cool (1962) and ‘kitchen sink’-style attempts at social realism, including West 11 (1963, recently released on DVD by Network and reviewed by us here) and I’ll Never Forget What’s’isname (1967). In the 1970s, Winner’s films became more outrageous and exploitative, beginning with this film, The Nightcomers (1971), and continuing with his Hollywood pictures such as Death Wish (1974). Winner’s 1970s films often divided audiences sharply or attracted harsh criticism: The Nightcomers, for example, was derided as ‘a listless and greedy parody’ of Henry James’ 1898 novella, The Turn of the Screw, of which The Nightcomers is a prequel of sorts (Raw, 2006: 67). The Nightcomers’ lack of subtletly, in its depiction of the sadomasochistic relationship between Quint and Miss Jessel, is in stark contrast with the ambiguities of Jack Clayton’s adaptation of The Turn of the Screw, The Innocents, released only ten years prior to Winner’s film.  The Nightcomers was financed privately, with Winner working for free and Brando working for a percentage of the film’s profits: the film had been prepared by Winner, with Brando in the lead role, but struggled to find financing owing to the fact that Brando was considered ‘box office poison’ (Raw, op cit.: 72). Brando was considered difficult to work with: his continued absences (allegedly owing to illness) from the set of Gillo Pontecorvo’s Queimada (Burn!, 1969), the costs of which were covered by an insurance company who had to ‘pay out a fortune’, led to a situation in which a major film insurer initially refused to insure the actor (Winner, 2005: 150). Additionally, Brando’s ten previous films had flopped with audiences; Universal reputedly asked Winner to persuade Brando to accept a payment of $300,000 from the studio and take The Nightcomers as the final film of a three film contract for Universal (ibid.). Of course, within a couple of years, Brando’s popularity would soar, owing to the successes of The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) and Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertoluccio, 1972): in fact, Coppola reputedly visited the set of The Nightcomers with the intention of coaxing Brando into taking the role of Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather. When completed, The Nightcomers struggled to find distribution in the US following its premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 1971 but was eventually bought by Avco Embassy. Winner suggested that the release be held back until after The Godfather had been released, to maximise the commercial potential of The Nightcomers, but the film was distributed prior to The Godfather. Released in the UK in 1972, the film was cut by the BBFC, who trimmed many of the scenes featuring the bound Miss Jessel. The Nightcomers was financed privately, with Winner working for free and Brando working for a percentage of the film’s profits: the film had been prepared by Winner, with Brando in the lead role, but struggled to find financing owing to the fact that Brando was considered ‘box office poison’ (Raw, op cit.: 72). Brando was considered difficult to work with: his continued absences (allegedly owing to illness) from the set of Gillo Pontecorvo’s Queimada (Burn!, 1969), the costs of which were covered by an insurance company who had to ‘pay out a fortune’, led to a situation in which a major film insurer initially refused to insure the actor (Winner, 2005: 150). Additionally, Brando’s ten previous films had flopped with audiences; Universal reputedly asked Winner to persuade Brando to accept a payment of $300,000 from the studio and take The Nightcomers as the final film of a three film contract for Universal (ibid.). Of course, within a couple of years, Brando’s popularity would soar, owing to the successes of The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) and Last Tango in Paris (Bernardo Bertoluccio, 1972): in fact, Coppola reputedly visited the set of The Nightcomers with the intention of coaxing Brando into taking the role of Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather. When completed, The Nightcomers struggled to find distribution in the US following its premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 1971 but was eventually bought by Avco Embassy. Winner suggested that the release be held back until after The Godfather had been released, to maximise the commercial potential of The Nightcomers, but the film was distributed prior to The Godfather. Released in the UK in 1972, the film was cut by the BBFC, who trimmed many of the scenes featuring the bound Miss Jessel.

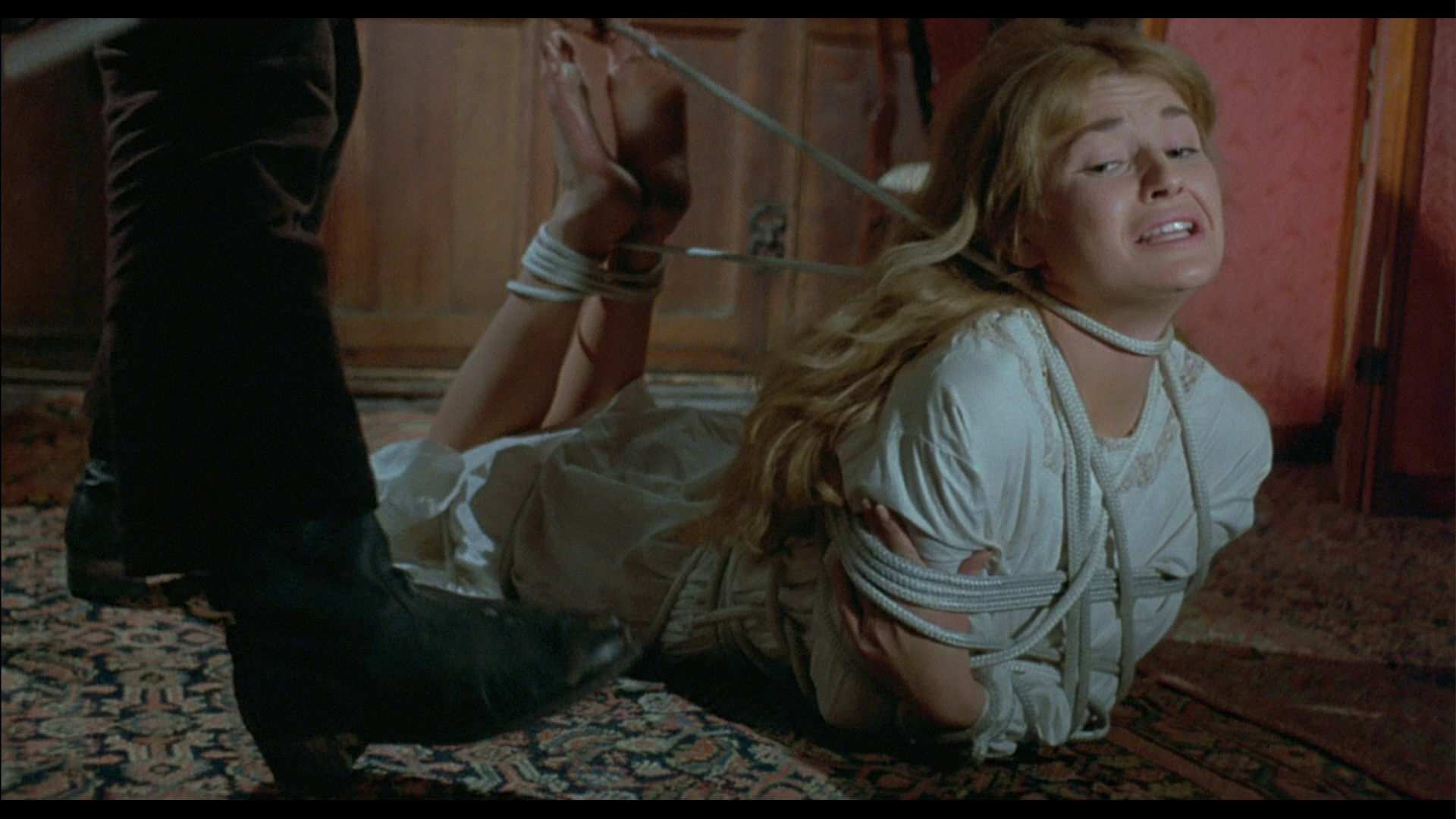

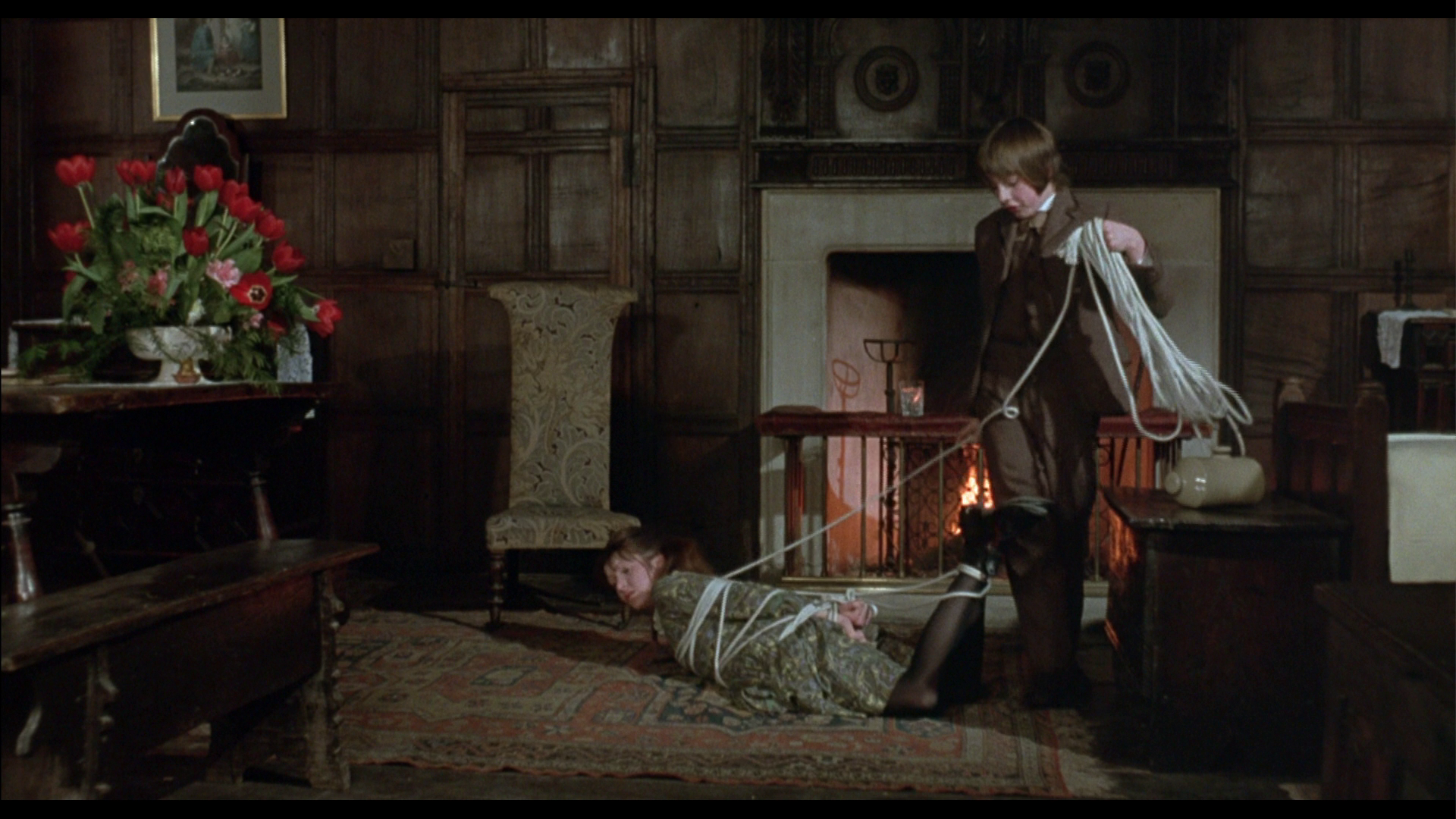

The springboard for Michael Winner’s The Nightcomers (1971) seems to have been Jack Clayton’s consideration during pre-production for The Innocents that the story, of Miles and Flora’s new governess’ ‘haunting’ by the ghosts of Quint and Miss Jessel, may work best as ‘a rather strange detective story and rather as though one accepts in principle the fact that all the important incidents have … occurred before we arrived on the scene’ (Clayton, quoted in Sinyard, 2000: 89; ellipsis in original). In light of this, Clayton considered, and then dismissed, the idea of structuring The Innocents around flashbacks, much like Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) or Robert Siodmak’s film noir The Killers (1946), which showed what had happened between the children Miles and Flora, gardener Quint and governess Miss Jessel prior to the arrival of the new governess (played in the film by Deborah Kerr) (ibid.). Winner’s film uses this idea as a starting-off point, constructing its narrative around Quint and Miss Jessel’s relationship prior to the arrival of the new governess, effectively functioning as a ‘prequel’ to The Turn of the Screw (and, by extension, The Innocents).  At the heart of the film are Miles and Flora, who are in effect abandoned by their only relative (Harry Andrews), into the care of Miss Jessel and Mrs Grose, who seem largely uninterested in the children. Only Quint appears willing to engage with them, taking on the role of a surrogate father. However, he is a domineering presence, answering the children’s questions in a curiously adult manner: ‘[a]s there is no one to restore patriarchal authority in a more just […] form, the children are corrupted’ (Raw, op cit.: 68). In the opening sequence, he illustrates his thesis that loving something deeply will result in death by putting on a show for the children: he places a lit cigarette in the mouth of a toad. The toad inhales the smoke and, eventually, explodes as a consequence. By night, Quint sneaks into Miss Jessel’s quarters where, unknowingly watched by the children, he and Miss Jessel engage in sadomasochistic sex. (In one such scene, Quint hogties Miss Jessel. Miles, who has watched this activity through the window of Miss Jessel’s room, later re-enacts this scene with his sister Flora. Flora complains, ‘Miles, it hurts’. Miles answers, ‘I think it’s meant to’. When Mrs Grose interrupts them, Miles tells the maid, ‘I’ll tell you exactly what we’ve been doing. We’ve been doing sex’. It’s a comic sequence that is also deeply unsettling.) Where, in The Turn of the Screw and The Innocents, Quint and Miss Jessel are arguably metaphors for the new governess’ growing awareness of her own sexuality, The Nightcomers depicts them as characters who are defined by their corporeality. Raw argues that if ‘The Innocents showed Miss Giddens gradually discovering the presence of sexual feelings within her, The Nightcomers depicts a world where sexual freedom runs rampant’ (ibid.). At the heart of the film are Miles and Flora, who are in effect abandoned by their only relative (Harry Andrews), into the care of Miss Jessel and Mrs Grose, who seem largely uninterested in the children. Only Quint appears willing to engage with them, taking on the role of a surrogate father. However, he is a domineering presence, answering the children’s questions in a curiously adult manner: ‘[a]s there is no one to restore patriarchal authority in a more just […] form, the children are corrupted’ (Raw, op cit.: 68). In the opening sequence, he illustrates his thesis that loving something deeply will result in death by putting on a show for the children: he places a lit cigarette in the mouth of a toad. The toad inhales the smoke and, eventually, explodes as a consequence. By night, Quint sneaks into Miss Jessel’s quarters where, unknowingly watched by the children, he and Miss Jessel engage in sadomasochistic sex. (In one such scene, Quint hogties Miss Jessel. Miles, who has watched this activity through the window of Miss Jessel’s room, later re-enacts this scene with his sister Flora. Flora complains, ‘Miles, it hurts’. Miles answers, ‘I think it’s meant to’. When Mrs Grose interrupts them, Miles tells the maid, ‘I’ll tell you exactly what we’ve been doing. We’ve been doing sex’. It’s a comic sequence that is also deeply unsettling.) Where, in The Turn of the Screw and The Innocents, Quint and Miss Jessel are arguably metaphors for the new governess’ growing awareness of her own sexuality, The Nightcomers depicts them as characters who are defined by their corporeality. Raw argues that if ‘The Innocents showed Miss Giddens gradually discovering the presence of sexual feelings within her, The Nightcomers depicts a world where sexual freedom runs rampant’ (ibid.).

Some critics of James’ novella have suggested that the governess is/was the corrupting influence in the lives of Miles and Flora: for example, in 1966 S Gorley Putt suggested that the governess was like a vampire, ‘dangerously self-deluded’ (Putt, quoted in Raw, op cit.: 69). The Nightcomers, on the other hand, places the blame for the corruption of Miles and Flora squarely in the hands of the film’s two patriarchs: Quint and the children’s (absent and detached) uncle. Although he is aware of the fact that, the children’s father having died, there is no longer any need for a valet at Bly House, the uncle allows Quint to stay on and, in addition to this, bestows Quint with the responsibility of looking after the house and the womenfolk within it. ‘The reason for this is clear’, Laurence Raw has noted, ‘The patriarchy in the house must be maintained, even if Quint is manifestly unsuitable for the task’ (ibid.). The film is in many ways Brando’s picture. Brando gives Quint an Oirish accent (the same exaggerated brogue he employed in Arthur Penn’s The Missouri Breaks, 1976), turning him into a social misfit of the kind that Brando became associated with following the release of The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953). At one point, a drunken Quint (and, according to Winner, an equally drunken Brando) delivers a monologue to the children that tells them of the time his father tried to swindle a group of gypsies by selling them, by the cover of night, a mangy old nag covered in paint and with a piece of ginger stuck ‘up the rear of the animal’. The outcome of this exercise was Quint’s father being stripped and nearly drowned, with Quint claiming this was the last time he saw his father – ‘And I wouldn’t lie to you, so help me God’. The monologue goes some way towards explaining Quint’s rabble-rousing dislike of authority (as the uncle rides away in his carriage, Quint doffs his cap and says, Goodbye, Sir’; but as the carriage pulls away, Quint sticks two fingers up at it and declares, ‘Straight up your arse, sir’) and his desire to provide a stable, paternal presence in the lives of the children. In Brando’s performance, Quint, Laurence Raw argues, is ‘at once repellent yet brutally attractive’ (Raw, op cit.: 67). Brando reputedly claimed that Winner allowed him free rein with the character, telling Brando that ‘I was a great actor and he wasn’t a great director’ and praising the fact Winner was ‘the only person I’ve ever met who doesn’t talk to me in the manner he thinks I like to be talked to’ (Brando, quoted in ibid.; Brando, quoted in Winner, op cit.:150). Some critics of James’ novella have suggested that the governess is/was the corrupting influence in the lives of Miles and Flora: for example, in 1966 S Gorley Putt suggested that the governess was like a vampire, ‘dangerously self-deluded’ (Putt, quoted in Raw, op cit.: 69). The Nightcomers, on the other hand, places the blame for the corruption of Miles and Flora squarely in the hands of the film’s two patriarchs: Quint and the children’s (absent and detached) uncle. Although he is aware of the fact that, the children’s father having died, there is no longer any need for a valet at Bly House, the uncle allows Quint to stay on and, in addition to this, bestows Quint with the responsibility of looking after the house and the womenfolk within it. ‘The reason for this is clear’, Laurence Raw has noted, ‘The patriarchy in the house must be maintained, even if Quint is manifestly unsuitable for the task’ (ibid.). The film is in many ways Brando’s picture. Brando gives Quint an Oirish accent (the same exaggerated brogue he employed in Arthur Penn’s The Missouri Breaks, 1976), turning him into a social misfit of the kind that Brando became associated with following the release of The Wild One (Laslo Benedek, 1953). At one point, a drunken Quint (and, according to Winner, an equally drunken Brando) delivers a monologue to the children that tells them of the time his father tried to swindle a group of gypsies by selling them, by the cover of night, a mangy old nag covered in paint and with a piece of ginger stuck ‘up the rear of the animal’. The outcome of this exercise was Quint’s father being stripped and nearly drowned, with Quint claiming this was the last time he saw his father – ‘And I wouldn’t lie to you, so help me God’. The monologue goes some way towards explaining Quint’s rabble-rousing dislike of authority (as the uncle rides away in his carriage, Quint doffs his cap and says, Goodbye, Sir’; but as the carriage pulls away, Quint sticks two fingers up at it and declares, ‘Straight up your arse, sir’) and his desire to provide a stable, paternal presence in the lives of the children. In Brando’s performance, Quint, Laurence Raw argues, is ‘at once repellent yet brutally attractive’ (Raw, op cit.: 67). Brando reputedly claimed that Winner allowed him free rein with the character, telling Brando that ‘I was a great actor and he wasn’t a great director’ and praising the fact Winner was ‘the only person I’ve ever met who doesn’t talk to me in the manner he thinks I like to be talked to’ (Brando, quoted in ibid.; Brando, quoted in Winner, op cit.:150).

Bill Harding, who wrote a biography of Michael Winner, suggested that in at least one respect, The Nightcomers got something ‘right’ which, in Jack Clayton’s The Innocents, was mishandled: Harding argues that in The Innocents, Deborah Kerr was ‘miscast’, as she was ‘too wholesome an actress to project the duality James implied in the psychology of the second governess’, whereas as Miss Jessel in The Nightcomers Stephanie Beacham was effective in ‘suggesting both a rigid respectability and the heated sexuality’ of the character (Harding, quoted in Raw, op cit.: 73). After one of their bondage sessions, Miss Jessel tells Quint, ‘I’m so ashamed’. ‘Bull… shit’, Quint replies, ‘You love as you can find love. That’s all’. ‘But all that pain’, Miss Jessel says, ‘All the hurt, the dirtiness of it, Quint’. ‘Well, what did you think when we started? It was to be kind?’, Quint asks her. ‘It was to be gentle’, Jessel tells him. ‘Do you believe it’s not pain when you’re born?’, Quint reasons, ‘Or it’s not so when you die? Do you think there’s no hurt when you love? Then you’re a hypocrite’. Beacham’s Miss Jessel is, by day, a repressed, prim Victorian woman; but by night, she is driven by desire to submit to the authority of the brutish, defiantly proletarian Quint. However, she maintains a distance between herself and Quint, telling him not to call her by her first name, Margaret, as ‘I cannot so give myself’. Where The Innocents ‘used The Turn of the Screw to hint at new possibilities for women, Winner uses the same text to reinforce patriarchal values and attitudes’ (ibid.: 72). Bill Harding, who wrote a biography of Michael Winner, suggested that in at least one respect, The Nightcomers got something ‘right’ which, in Jack Clayton’s The Innocents, was mishandled: Harding argues that in The Innocents, Deborah Kerr was ‘miscast’, as she was ‘too wholesome an actress to project the duality James implied in the psychology of the second governess’, whereas as Miss Jessel in The Nightcomers Stephanie Beacham was effective in ‘suggesting both a rigid respectability and the heated sexuality’ of the character (Harding, quoted in Raw, op cit.: 73). After one of their bondage sessions, Miss Jessel tells Quint, ‘I’m so ashamed’. ‘Bull… shit’, Quint replies, ‘You love as you can find love. That’s all’. ‘But all that pain’, Miss Jessel says, ‘All the hurt, the dirtiness of it, Quint’. ‘Well, what did you think when we started? It was to be kind?’, Quint asks her. ‘It was to be gentle’, Jessel tells him. ‘Do you believe it’s not pain when you’re born?’, Quint reasons, ‘Or it’s not so when you die? Do you think there’s no hurt when you love? Then you’re a hypocrite’. Beacham’s Miss Jessel is, by day, a repressed, prim Victorian woman; but by night, she is driven by desire to submit to the authority of the brutish, defiantly proletarian Quint. However, she maintains a distance between herself and Quint, telling him not to call her by her first name, Margaret, as ‘I cannot so give myself’. Where The Innocents ‘used The Turn of the Screw to hint at new possibilities for women, Winner uses the same text to reinforce patriarchal values and attitudes’ (ibid.: 72).

Video

Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec and takes up approximately 19Gb of space on a single-layered disc. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec and takes up approximately 19Gb of space on a single-layered disc.

Robert Paynter’s photography, with its painterly compositions, is given a vibrant presentation here, with good, finely-balanced contrast making both the daylight scenes (dominated by autumnal greens and greys) and the nighttime scenes (in which Quint visits Miss Jessel) equally impressive. There’s a strong level of detail above that of the DVDs that are available. The source print is very clean. A seemingly natural level of grain is present: there’s no obvious evidence of excessive digital sharpening or noise reduction, though the ‘texture’ of the film sometimes feels a little crushed by the admittedly stingy encode. The film was cut by the BBFC for its original release in 1972; the BBFC demanded that most of the shots of the bound Miss Jessel be removed. However, subsequent home video versions have been intact. This presentation is uncut and runs for 96:43 mins. NB. Some large screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM two channel track, which demonstrates reasonably good range, especially in the sequences which make use of Jerry Fielding’s lyrical score. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes a trailer (1:55), a teaser trailer (0:30) and a stills gallery (2:29).

Overall

As Neil Sinyard has suggested, Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw defines evil in terms that engage with the values of the Victorian era: as Sinyard notes, ‘[o]ne of the things which most offends the governess about Quint’s affair with Miss Jessel is its disturbance of her sense of social decorum—the servant [Quint] not knowing his place’ (Sinyard, 2013: 33). Underneath this is the awareness of the ‘sexual nature of the relationship’ between Quint and Miss Jessel, ‘and the fact that the children may have seen something’ in relation to this; this ‘generates from the governess a protective attitude towards them that borders on possessiveness’ (ibid.). However, Clayton believed that Quint and Miss Jessel had simply had ‘a perfectly normal sexual relationship’ (ibid.: 33-4); Winner, by contrast, envisages Quint and Jessel’s relationship as one that is predicated on bondage and powerplay that has more in common with Pauline Réage than Henry James. The Nightcomers takes the subtext of James’ novella and makes it simply text, stripping the story of Miles and Flora (and Quint and Miss Jessel) of any ambiguity. On the other hand, the film features some strong photography and a lyrical score by Jerry Fielding which echoes some of the motifs found in Fielding’s score for Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971). As Neil Sinyard has suggested, Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw defines evil in terms that engage with the values of the Victorian era: as Sinyard notes, ‘[o]ne of the things which most offends the governess about Quint’s affair with Miss Jessel is its disturbance of her sense of social decorum—the servant [Quint] not knowing his place’ (Sinyard, 2013: 33). Underneath this is the awareness of the ‘sexual nature of the relationship’ between Quint and Miss Jessel, ‘and the fact that the children may have seen something’ in relation to this; this ‘generates from the governess a protective attitude towards them that borders on possessiveness’ (ibid.). However, Clayton believed that Quint and Miss Jessel had simply had ‘a perfectly normal sexual relationship’ (ibid.: 33-4); Winner, by contrast, envisages Quint and Jessel’s relationship as one that is predicated on bondage and powerplay that has more in common with Pauline Réage than Henry James. The Nightcomers takes the subtext of James’ novella and makes it simply text, stripping the story of Miles and Flora (and Quint and Miss Jessel) of any ambiguity. On the other hand, the film features some strong photography and a lyrical score by Jerry Fielding which echoes some of the motifs found in Fielding’s score for Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971).

The Nightcomers has a lack of subtlety that may be likened to using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut. However, there’s an enormous sensuality within both Brando and Beacham’s performances, and despite – or perhaps because of – some of its oddities (for example, the graphic dream sequence in which Miles imagines shooting an arrow through the throat of Mrs Grose) The Nightcomers is in many respects a fascinating film. The presentation of the film on this disc is very good, clearly an improvement over the various DVDs that are available. (However, it’s worth hanging on to the US DVD, if you have it, as that disc contains a commentary by Winner.)  References: Raw, Laurence, 2006: Adapting Henry James to the Screen: Gender, Fiction, and Film. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Sinyard, Neil, 2000: British Film Makers: Jack Clayton. Manchester University Press Sinyard, Neil, 2013: Filming Literature: The Art of Screen Adaptation. London: Routledge Winner, Michael, 2005: Winner Takes All: A Life of Sorts. London: Robson Books

This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|