|

|

Island of Death AKA Pedhia Tou Dhiavolou, Ta (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd May 2015). |

|

The Film

Island of Death (Nico Mastorakis, 1976) Island of Death (Nico Mastorakis, 1976)

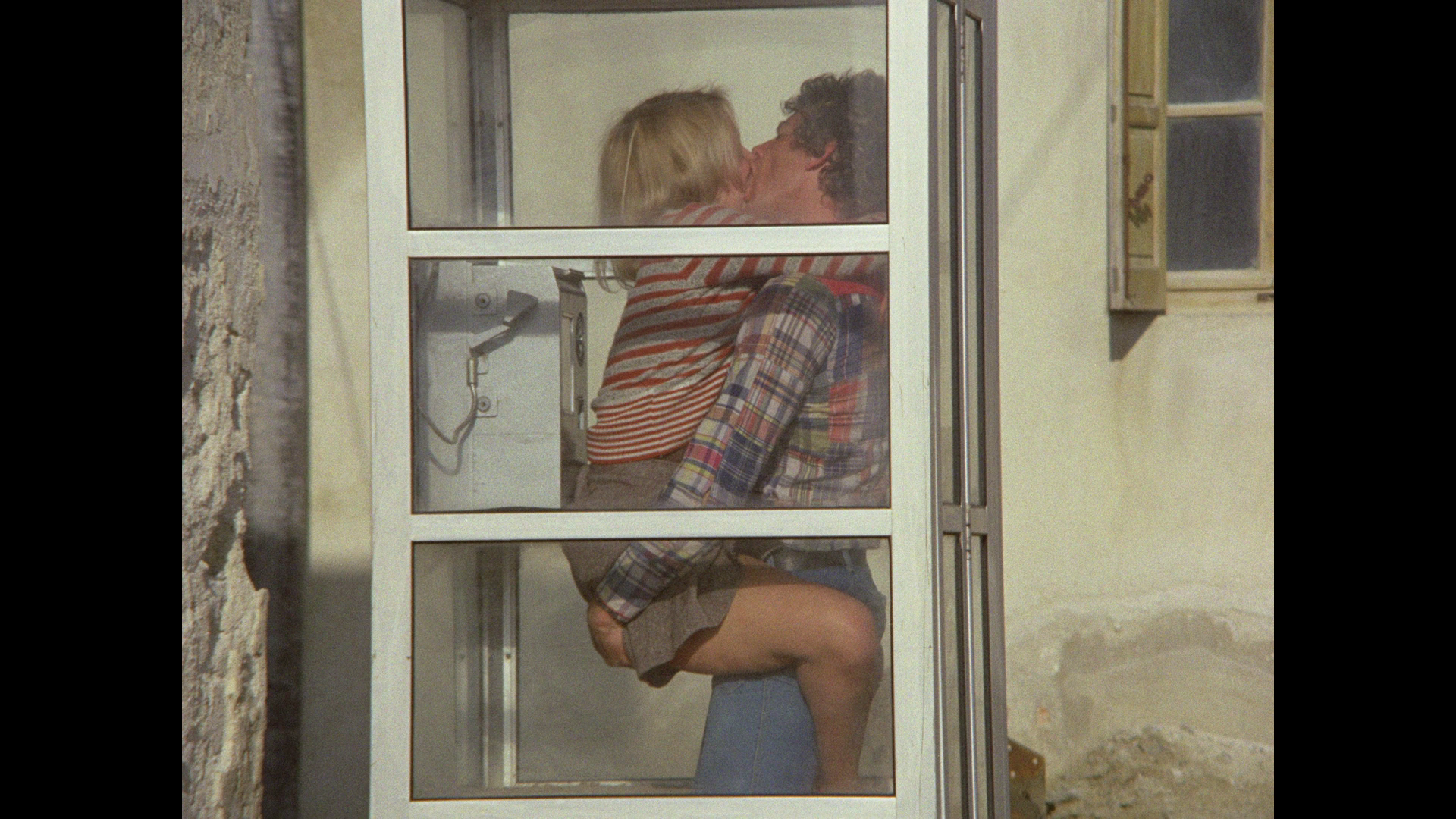

A film now most widely known by a title which was never intended to be associated with it (at least until its UK VHS release from AVI in 1982), Nico Mastoraki’s Island of Death was originally released in UK cinemas as A Craving for Lust, on a double bill with Omiros Efstratiadis’ Her Naked Flesh (Diamantia sto gymno sou soma/Diamonds on Her Naked Flesh, made in 1972). (The title Island of Death was also an alternate title for the UK VHS release of Narcisco Ibanez Serrador’s ¿Quien puede matar a un niño?/Who Can Kill a Child?, 1975, with which Mastorakis’ film shares both its narrative’s escalation of unconscionable violence and a focus on English protagonists holidaying on a Mediterranean island.) Because of its catalogue of depravities (a suggested act of bestiality, a scene in which one of the protagonists urinates over an elderly seductress), and possibly because of its hyperbolic and satirical approach to the concept of self-appointed ‘moral guardians’, Mastorakis’ film became one of the more notorious and enduring entries on the Director of Public Prosecutions’ list of ‘video nasties’: films which were, if tried in court, likely to be found ‘obscene’ under the definition laid out in the Obscene Publications Act. Island of Death was the second film in the prolific career of its writer-producer-director, Nico Mastorakis, who was inspired to make the picture after the commercial success of Tobe Hooper’s independent horror film The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Whilst there are few (if any) narrative similarities between Hooper’s film and Island of Death, Mastorakis deduced from the success of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre that the secret to making a commercially successful first feature was to produce a picture that was shocking, and to this end Mastorakis tried to cram as many exploitative elements into Island of Death as possible. Mastorakis admits, in the interview contained on this disc (and ported over from the 2002 Allstar Pictures DVD release), that he doesn’t like this type of film, and that he wouldn’t let his own (adult) children watch it; but the picture, he says, was constructed to make money and has acquired a strong cult following that Mastorakis embraces. The film focuses on Christopher (Robert Behling, credited here as Bob Belling) and Celia (Jane Lyle, credited here as Jane Ryall), a young British couple who arrive on the Greek island of Mykonos. They meet Paul Kemp, an American who lives on the island. After telling the couple that ‘This time of year there aren’t many strangers around’, Kemp points Chris and Celia in the direction of a hotel.  However, Chris and Celia are far from the charming young couple they appear to be. Their outwardly pleasant façade hides their obsessive need to ‘punish’ those they perceive as deviant, ostensibly in the name of God. Their own deviance is signalled early in the film when, after arriving on Mykonos, Chris proposes that they call his mother in London whilst he and Celia make love in the telephone booth. However, unbeknownst to Chris, Foster (Gerard Gonalons) is listening to the call, having tapped Chris’ mother’s telephone. Foster is a detective: Chris and Celia are wanted for undisclosed crimes they have committed in Britain. Foster traces Chris and Celia to Mykonos. However, Chris and Celia are far from the charming young couple they appear to be. Their outwardly pleasant façade hides their obsessive need to ‘punish’ those they perceive as deviant, ostensibly in the name of God. Their own deviance is signalled early in the film when, after arriving on Mykonos, Chris proposes that they call his mother in London whilst he and Celia make love in the telephone booth. However, unbeknownst to Chris, Foster (Gerard Gonalons) is listening to the call, having tapped Chris’ mother’s telephone. Foster is a detective: Chris and Celia are wanted for undisclosed crimes they have committed in Britain. Foster traces Chris and Celia to Mykonos.

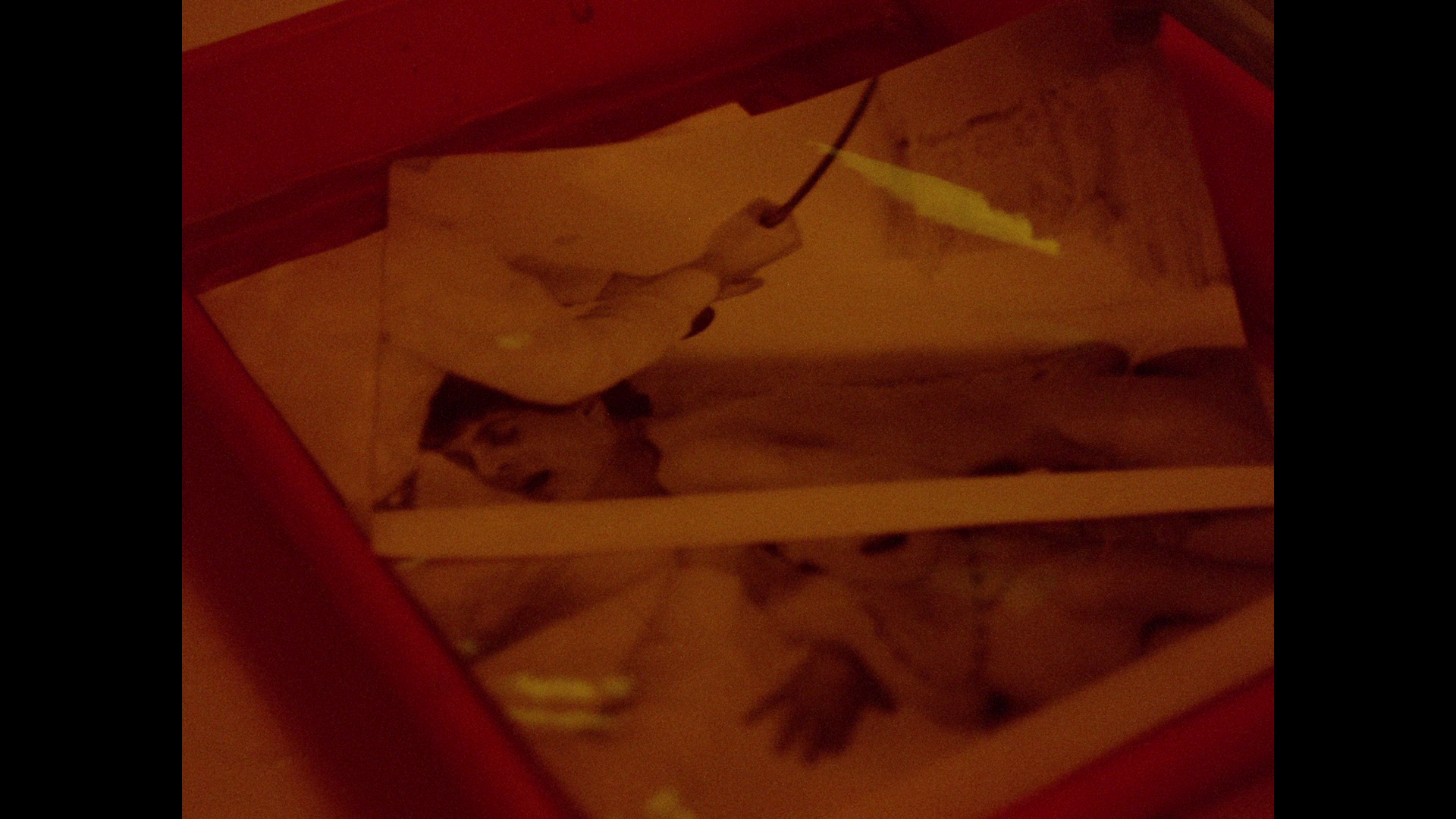

From the outset, in their desire to punish those who fall outside their strict moral code, Chris and Celia are presented as deviants themselves. Their own perverse ethos is signalled early in the film, when they make love in the telephone booth whilst calling Chris’ mother in London. (This is made even more unsettling by the ‘twist’ at the end of the picture.) Shortly after this, they visit a restaurant and meet a French painter who is there to restore a chapel on the island. ‘I don’t like that man over there’, Chris tells Celia, ‘He’s a dirty bastard. You don’t know what he’s thinking about you’. Celia recognises Chris’ delusions for what they are, and for the first of a number of times in the film she suggests Chris is ‘crazy’: ‘Are you crazy or something?’, she asks, ‘He’s not even looking at us’. Outside the restaurant, Chris watches a couple making love in their own home; gazing through the window of their bedroom, Chris observes bitterly, ‘Bitch! Take a look […] It’s not her husband. She’s a bitch […] If I was her husband, I’d kill her’.  Chris is obsessed with documenting his crimes, using photography as a means to do so. Celia also buys him a red notebook from Paul’s shop, in which to document their exploits (‘This’ll make a nice diary for us’), but Chris initially resists, claiming that the red notebook will bring them bad luck. Chris goads Celia into flirting with the painter and photographs the couple fucking in field whilst muttering under his breath, ‘Pervert’. Chris takes the painter’s positive response to Celia’s flirtatious advances as an index of his perversion, which in Chris’ schema needs to be punished violently. He ties a rope around the painter’s neck and tortures him, dragging him to the floor and kicking him aggressively. ‘Oh, my God’, the painter declares. ‘Your God is right there. Go on, ask him to help you now’, Chris taunts him. He and Celia crucify the painter, nailing him to the floor, and force him to drink paint. ‘In the name of the almighty God who purifies perversion, you sinful man, I crucify you’, Chris asserts during this act. Chris is obsessed with documenting his crimes, using photography as a means to do so. Celia also buys him a red notebook from Paul’s shop, in which to document their exploits (‘This’ll make a nice diary for us’), but Chris initially resists, claiming that the red notebook will bring them bad luck. Chris goads Celia into flirting with the painter and photographs the couple fucking in field whilst muttering under his breath, ‘Pervert’. Chris takes the painter’s positive response to Celia’s flirtatious advances as an index of his perversion, which in Chris’ schema needs to be punished violently. He ties a rope around the painter’s neck and tortures him, dragging him to the floor and kicking him aggressively. ‘Oh, my God’, the painter declares. ‘Your God is right there. Go on, ask him to help you now’, Chris taunts him. He and Celia crucify the painter, nailing him to the floor, and force him to drink paint. ‘In the name of the almighty God who purifies perversion, you sinful man, I crucify you’, Chris asserts during this act.

Later, Paul invites Chris and Celia to his engagement party. Despite Paul’s outwardly camp behaviour, Chris is surprised to discover the host is gay and is engaged to a man, Jonathan. At the party, they also meet Patricia Desmond (Jessica Dublin), a wealthy and promiscuous older woman who preys on younger men, and Leslie (Jannice McConnell), a lesbian and a heroin addict. Chris and Celia target Paul and his lover Jonathan first. ‘I enjoy punishing perversion’, Chris narrates, ‘Paul Kemp was a filthy creature, a bloody homosexual that didn’t deserve to live. And the other guy? Shit! How disgusting it was to see a man lying there like a whore!’ Chris and Celia burst in on Paul and Jonathan, Chris slaying Paul with a sword and Celia blowing Jonathan’s brains out with a revolver. ‘God punishes perversion, and I’m his angel with a flaming sword, sent to punish dirty worms’, Chris declares.  Much of the controversy surrounding the film seems to centre on a confusion of the ‘voice’ of the protagonists (and especially that of Chris, who narrates) with the ‘voice’ of the film’s author, Mastorakis: some critics have suggested that Mastorakis depicts Chris and Celia’s ‘crusade’ sympathetically. However, as the above examples might suggest, Chris’ rhetoric is hollow – undercut by his own behaviour, and signalled from the start of the film, as he fucks Celia in the telephone booth whilst calling his mother – and in its ridiculousness (‘sent to punish dirty worms’), laced with irony. The film offers a hyperbolic and satirical approach to the concept of self-appointed moral guardians, which no doubt enraged the UK’s own moral entrepreneurs – such as Mary Whitehouse’s moral watchdog organisation The National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, which in 1983 campaigned for regulation of home video, something which came about in the form of the 1984 Video Recordings Act. In fact, in terms of its outrageous hyperbole, Island of Death is almost like a comic book on film, and in its satirical approach towards moral guardians and moral watchdogs the film could be likened to the subversive ‘one shot’ comic strips in a roughly contemporaneous publication such as 2000AD (1977-present). Much of the controversy surrounding the film seems to centre on a confusion of the ‘voice’ of the protagonists (and especially that of Chris, who narrates) with the ‘voice’ of the film’s author, Mastorakis: some critics have suggested that Mastorakis depicts Chris and Celia’s ‘crusade’ sympathetically. However, as the above examples might suggest, Chris’ rhetoric is hollow – undercut by his own behaviour, and signalled from the start of the film, as he fucks Celia in the telephone booth whilst calling his mother – and in its ridiculousness (‘sent to punish dirty worms’), laced with irony. The film offers a hyperbolic and satirical approach to the concept of self-appointed moral guardians, which no doubt enraged the UK’s own moral entrepreneurs – such as Mary Whitehouse’s moral watchdog organisation The National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, which in 1983 campaigned for regulation of home video, something which came about in the form of the 1984 Video Recordings Act. In fact, in terms of its outrageous hyperbole, Island of Death is almost like a comic book on film, and in its satirical approach towards moral guardians and moral watchdogs the film could be likened to the subversive ‘one shot’ comic strips in a roughly contemporaneous publication such as 2000AD (1977-present).

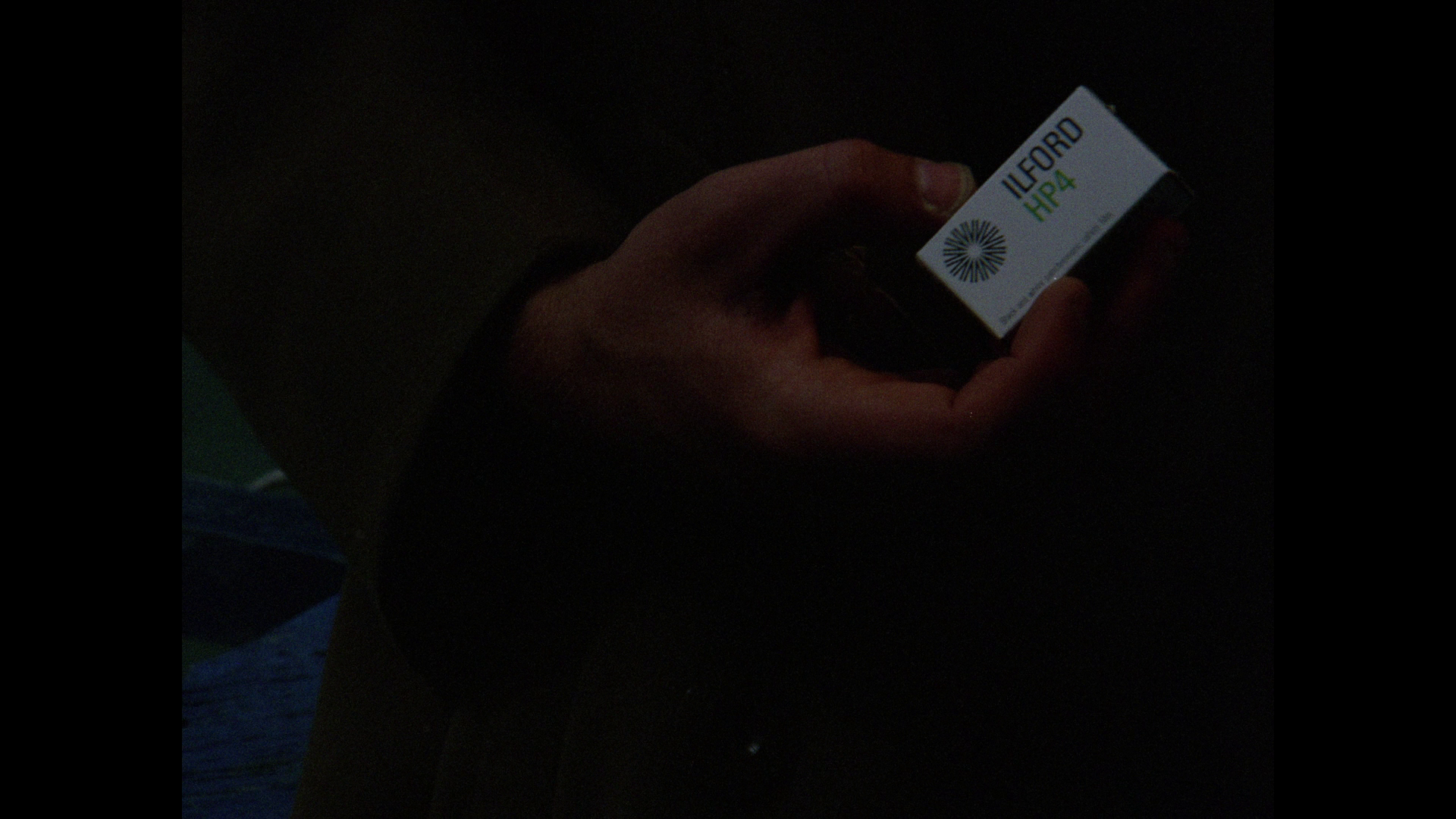

The film begins with Christopher trapped in a lime pit, as via a voiceover narration he reflects on his predicament: ‘I can’t believe it. Is it this damn book that brought me such bad luck?’, he narrates as Mastorakis cuts to a close-up of a red notebook, which is also in the lime pit. ‘Will it end this way?’, Chris asks in his narration, ‘Do I have a chance? Oh, God, please let me have a chance. Please give me a chance’. The bulk of the film’s narrative is thus presented as an extended analepsis/flashback from Christopher’s point-of-view, beginning with his and Celia’s arrival on the island. Chris’ Nikon 35mm SLR camera, with its attached AutoWinder, features in many of the scenes: as Celia and the painter fuck in the field, we watch from Chris’ point-of-view as he observes through the viewfinder of his Nikon. Mastorakis cuts into the action black-and-white still frames of Celia and the painter, as if they are prints from the frames Chris has captured on the negative in his camera. (Incidentally, there’s much focus on the process of photography: in one sequence, we see Chris and Celia developing prints in the darkroom they’ve presumably set up in the hotel, and later we are presented with a shot of Chris loading his camera that allows us to identify the film he’s using as Ilford’s HP4.) There’s a repeated motif within the editing of the film that foregrounds the extent to which most of the film could be said to take place through Chris’ viewfinder: abrupt cuts to black (rather than fades), denoting the ends of narrative sequences, are accompanied on the audio track by the sound of the Nikon’s AutoWinder firing, before a cut into the start of the next sequence. The film’s original opening titles (recreated for this release: prior DVDs had included one of the songs from the film’s soundtrack over the opening titles) featured the sound of the Nikon’s AutoWinder firing as each credit (plain white text on a red background) appeared on screen.  Aside from the satirical depiction of moral crusaders, Island of Death is interesting from the perspective of its depiction of Chris and Celia’s relationship with Mykonos. From the outset, Christopher and Celia see Mykonos as a place that they can exploit. ‘I always know right from the start if I’m going to love or hate a place’, Chris says in his narration, ‘and that’s why I loved this island. Mykonos, it’s called. Nothing more than a deserted rock, white houses and small, narrow streets. Three hundred and sixty-five churches. A place where they worship God. The perfect place’. Chris (patronisingly) sees the island as a place of innocence that has been corrupted by outside influences, without recognising the irony of his position (as, himself, an outsider to the island): ‘This place belongs to innocent people’, he asserts, ‘They have rights here. And if this island’s full of shit, I’ll help them clean it up’. Celia expresses doubts about Chris’ agenda: ‘Maybe they don’t want to do that. They live with those people’, she asserts. ‘Nonsense. No one wants to live with perversion’, Chris declares, ‘Children must be brought up the proper way. Nature is strong’.  Chris and Celia’s final flight from the police (in which Celia is clad symbolically in a white nightdress) takes them through idyllic fields and then, as if to deflate the perception of the island as ‘pure’ or ‘innocent’, over a landfill. They pass through a monastery, and finally they arrive at the cottage of a shepherd (Nikos Tsachiridis), a man who speaks no English (and, in fact, seems unable to speak any language at all). This almost symbolic journey, filmed mostly in long shots punctuated by tight close-ups, combined with Celia’s flowing white nightdress and, ultimately, the mute, coarse performance of the shepherd, is like a sequence from a film by Pasolini. Celia reveals that she has dreamt about the shepherd raping her and killing Chris, to which Chris declares, ‘Nonsense. He may be primitive but he’s innocent’, and asserts that this is a validation of his earlier claim that ‘this land belongs to the innocent people’. (Earlier, again unaware of the irony of his words, Chris has told Celia that such events ‘only happen in nightmares’.) As if to punctuate Chris’ earlier patronising rhetoric about the ‘innocence’ of the islanders and the necessity of Chris’ crusade – in their name – against perversion, the shepherd attacks Chris and Celia, raping Celia (who then apparently develops an attraction to the shepherd) and throwing Chris into the lime pit from which, in the opening sequence, Chris narrates. Chris and Celia’s final flight from the police (in which Celia is clad symbolically in a white nightdress) takes them through idyllic fields and then, as if to deflate the perception of the island as ‘pure’ or ‘innocent’, over a landfill. They pass through a monastery, and finally they arrive at the cottage of a shepherd (Nikos Tsachiridis), a man who speaks no English (and, in fact, seems unable to speak any language at all). This almost symbolic journey, filmed mostly in long shots punctuated by tight close-ups, combined with Celia’s flowing white nightdress and, ultimately, the mute, coarse performance of the shepherd, is like a sequence from a film by Pasolini. Celia reveals that she has dreamt about the shepherd raping her and killing Chris, to which Chris declares, ‘Nonsense. He may be primitive but he’s innocent’, and asserts that this is a validation of his earlier claim that ‘this land belongs to the innocent people’. (Earlier, again unaware of the irony of his words, Chris has told Celia that such events ‘only happen in nightmares’.) As if to punctuate Chris’ earlier patronising rhetoric about the ‘innocence’ of the islanders and the necessity of Chris’ crusade – in their name – against perversion, the shepherd attacks Chris and Celia, raping Celia (who then apparently develops an attraction to the shepherd) and throwing Chris into the lime pit from which, in the opening sequence, Chris narrates.

In its exploration of the relationships that exist between cultural outsiders or tourists (and their patronising, often naïve interpretations of the ‘purity’ or ‘simplicity’ of the cultures they are visiting) and locals, Island of Death explores a similar dynamic to films such as Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), in which American mathematician David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) struggles to integrate himself into the community of a Cornish village, and John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) – with its focus on a quartet of men from the city who fail to recognise the dangers of their trip into rural America. Like those films, Island of Death foregrounds the concealed brutality of the white, bourgeois ‘tourist’ (in this case, the couple of Chris and Celia), except in Mastorakis’ film – as compared with Peckinpah and Boorman’s pictures – the locals do nothing to provoke the ire of Chris and Celia, other than simply pursue their own desires. (Island of Death’s blackly comic excesses, on the other hand, arguably find a closer corollary in the BBC’s sitcom The League of Gentlemen, 1999-2002, which in a similarly reflexive manner, also explores the tensions between the cultural outsider and ‘local people’.)  Island of Death was classified by the BBFC for cinema release in 1976 under two titles (A Craving for Lust and Devils in Mykonos), with cuts of almost fourteen minutes. AVI’s VHS release made its way on to the DPP’s list of ‘video nasties’ that were likely to be found obscene under the Obscene Publications Act. When a heavily cut version of the film was submitted (post-Video Recordings Act) to the BBFC for video classification in 1987 (under yet another title, Psychic Killer II), it was rejected and effectively banned from home video until 2002, when it was resubmitted by VIPCO and passed with four minutes and nine seconds of cuts. Resubmitted by Arrow Video in 2010, Island of Death was finally passed uncut for home video distribution. Island of Death was classified by the BBFC for cinema release in 1976 under two titles (A Craving for Lust and Devils in Mykonos), with cuts of almost fourteen minutes. AVI’s VHS release made its way on to the DPP’s list of ‘video nasties’ that were likely to be found obscene under the Obscene Publications Act. When a heavily cut version of the film was submitted (post-Video Recordings Act) to the BBFC for video classification in 1987 (under yet another title, Psychic Killer II), it was rejected and effectively banned from home video until 2002, when it was resubmitted by VIPCO and passed with four minutes and nine seconds of cuts. Resubmitted by Arrow Video in 2010, Island of Death was finally passed uncut for home video distribution.

This release of the film is uncut and runs for 106:00 mins.

Video

An often overlooked aspect of Island of Death is just how well-photographed the film is. Fascinating, well-balanced compositions abound, and much of the film is shot almost like a travelogue documentary. Mastorakis also makes effective use of extreme wide-angle/fisheye lenses, during the scenes in which Chris and Celia attack their victims, seemingly as a way of using the visual distortion enabled by the lens to comment on the distortion within Chris and Celia’s worldview. An often overlooked aspect of Island of Death is just how well-photographed the film is. Fascinating, well-balanced compositions abound, and much of the film is shot almost like a travelogue documentary. Mastorakis also makes effective use of extreme wide-angle/fisheye lenses, during the scenes in which Chris and Celia attack their victims, seemingly as a way of using the visual distortion enabled by the lens to comment on the distortion within Chris and Celia’s worldview.

Taking up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered disc, this presentation of Island of Death is based on a new 2k restoration by Arrow, and presents the film in an aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Colour consistency is evident from the opening titles sequence, which features the titles as white text on a vivid red background, as the sound of Chris’ Nikon’s AutoWinder accompanies the appearance of each credit. (This is a recreation of the film’s original titles sequence, which is apparently missing from the original film elements and in previous DVD releases has been replaced by an alternate titles sequence that is accompanied by one of the songs from the film’s soundtrack.) Also striking are the rich blues of the sky and water as Chris and Celia’s boat arrives at Mykonos, and the vivid yellow of the fisherman’s nets laid out on the quay.  A superb encode retains the natural grain structure of 35mm film, and contrast within the presentation is very good too. The day-for-night filtering in some sequences (for example, the murder of Paul Kemp) seems stronger in this presentation than in some of the earlier VHS and DVD releases, and some of the details within the sequence in which Chris kills Kemp with a sword are swallowed by the shadows (for example, the expression on Kemp’s face as Chris runs him through with the sword). (Interestingly, in the interview with Mastorakis that’s included on this disc, and ported over from the Allstar DVD release of 2002, this sequence is presented sans the day-for-night filtering.) Other sequences (for example, the sequence in which Celia fucks the painter whilst Chris captures the moment with his Nikon) make heavy use of diffuse light, almost as if to suggest a dreamlike atmosphere – as befitting the framing of the bulk of the narrative as Chris’ deathbed reflections. A superb encode retains the natural grain structure of 35mm film, and contrast within the presentation is very good too. The day-for-night filtering in some sequences (for example, the murder of Paul Kemp) seems stronger in this presentation than in some of the earlier VHS and DVD releases, and some of the details within the sequence in which Chris kills Kemp with a sword are swallowed by the shadows (for example, the expression on Kemp’s face as Chris runs him through with the sword). (Interestingly, in the interview with Mastorakis that’s included on this disc, and ported over from the Allstar DVD release of 2002, this sequence is presented sans the day-for-night filtering.) Other sequences (for example, the sequence in which Celia fucks the painter whilst Chris captures the moment with his Nikon) make heavy use of diffuse light, almost as if to suggest a dreamlike atmosphere – as befitting the framing of the bulk of the narrative as Chris’ deathbed reflections.

There are minor marks and examples of debris here and there, mostly in the fifth reel of the film, which also features a noticeable pulsing effect. The notes on the restoration that are included in the booklet state that the fifth reel was unfortunately damaged extensively by solvents; this reel has dirt, debris and scratches that are not found elsewhere in the film, and some lost frames in this reel have been reinserted from a SD source. In all, it’s a very impressive presentation of the film that, by upping the ante in terms of detail and colour consistency whilst retaining as much of the organic structure of 35mm film as is possible within a digital medium, reminds the viewer of just how well-photographed Island of Death is. The damage evident within the film’s fifth reel is regrettable but unavoidable, given the state of the source materials. The previous DVD releases were reasonably good, but this Blu-ray easily trumps them and is almost like watching the film anew. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented, in English, via a lossless LPCM 1.0 mono track. As the booklet notes state, this track was transferred by Mastorakis prior to Arrow’s involvement in the restoration. There’s a hiss evident within it, which is more prevalent during some sequences than others, and a recurring ‘flutter’. Some of this seems to be the product of production techniques (as the hiss sometimes disappears with an onscreen edit), but some of it, no doubt, is down to deterioration of the original sound elements. The background hiss and flutter can be distracting at times but, given the state of the original materials and the absence of a ‘clean’ transfer of the audio track, is acceptable. The lossless track certainly demonstrates a dynamic range that is lacking in the lossy tracks that were included on the film’s various DVD releases; this can be evident, particularly, in the sequences featuring music. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc is packed with contextual material, including: The disc is packed with contextual material, including:

‘Exploring Island of Death’ (38:25). This new interview with Stephen Thrower offers a reflection on Island of Death that begins with a discussion of the picture’s history on home video and its many alternate titles. In reference to the film’s UK cinema release (originally submitted to the BBFC under Mastorakis’ preferred title of Devils in Mykonos and cut by almost fourteen minutes), Thrower suggests that after the BBFC cuts, what was left was a predominantly softcore sex picture, hence the retitling of the film as A Craving for Lust. In reference to the film’s original title, Devils in Mykonos, Thrower suggests that there is no small amount of ambiguity: who are the ‘devils’ alluded to by this title, Chris and Celia or those they target? Mastorakis’ career, and his trajectory from television to cinema (with his directorial debut, the 1974 paranormal thriller Death Has Blue Eyes, retitled Parapsychics on video), is discussed, as is the oft-repeated story that Mastorakis was inspired to make Island of Death after viewing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at a cinema in Athens. From here, Thrower talks about Mastorakis’ career after Island of Death (his involvement in The Greek Tycoon, The Next One, Blind Date). Thrower reflects on the film’s performances, and suggests that there is ‘something strange and a little sort of sideways about [Jane Ryall’s] performance that helps to convince that you’re dealing with someone unbalanced’. On the other hand, Bob Behling ‘gives a more solid, dependable performance’. Thrower suggests that the use of Chris’ Nikon and the sound of the camera’s AutoWinder within the film’s editing suggests that the audience is, metaphorically speaking, looking through Chris’ viewfinder for much of the film’s running time, something which leads some viewers to confuse Mastorakis’ ‘voice’ as the film’s director with the skewed perspective of Chris and Celia. Talking about the film’s depiction of its gay characters, Thrower argues that ‘what tends to happen with a director that has a bad attitude about gay people [is that] they don’t put them in their films’. Mykonos, Thrower says, was ‘famous for its gay nightlife’, and thus the presence of Paul Kemp, Jonathan and Leslie (as the film’s gay characters) is organic rather than forced by Mastorakis. Commenting on the violence and the film’s photography, Thrower suggests that Island of Death is a ‘daylight horror’, because many of its horrific scenes are shot in stark sunlight. The excessive aspects of the film’s murder scenes, Thrower argues, suggest a ‘theatricality’ within the persona of Chris and make sense within that context. Thrower also offers some interesting observations on the film’s music. The lyrics in the songs are ‘from Mars’, he argues, and the music is of a very mid-1970s pop song style. Thrower’s argument is that this reflects the bizarre mentality of the film’s protagonists, as does the use of the track ‘Can You Call It Love?’ over the scene in which Chris watches Leslie and her lesbian lover making love in Leslie’s home. Thrower also compares the film’s use of music with David Hess’ score for Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972): in both cases, the films use music as an attempt to capture the mentality of their criminal protagonists. ‘Return to Island of Death’ (16:57). In this fascinating piece, Mastorakis revisits the film’s locations and talks with some of the people who collaborated on the film’s production.  ‘Nico Mastorakis interview (23:43). This interview with Mastorakis was originally included on the 2002 Allstar DVD release of Island of Death and has been seen on a number of the film’s subsequent DVD releases. Mastorakis talks about his career’s trajectory and suggests that Island of Death was a ‘recipe movie’ which was made simply to make money and therefore contains few of the elements that interest him personally. The script, he says, was written ‘formulaically’ in one week. ‘Nico Mastorakis interview (23:43). This interview with Mastorakis was originally included on the 2002 Allstar DVD release of Island of Death and has been seen on a number of the film’s subsequent DVD releases. Mastorakis talks about his career’s trajectory and suggests that Island of Death was a ‘recipe movie’ which was made simply to make money and therefore contains few of the elements that interest him personally. The script, he says, was written ‘formulaically’ in one week.

Mastorakis distances himself from the film somewhat by arguing that ‘Movies are not always a form of artistic expression’ for their filmmakers: the film is one ‘that I myself don’t take pleasure in watching’, although he ‘accept[s] the fact that some people, for their own [...] complex reasons, love to watch the movie’. However, Mastorakis claims he wouldn’t let his own (adult) daughter watch the picture. Mastorakis talks in some detail about the film’s makeup effects and, thankfully, reveals that the goat wasn’t killed. He reflects on censorship, saying that ‘I like to think it doesn’t exist’ and declaring, ‘I’m totally opposed to censorship of films for adults’: censorship is ‘totally medieval […] and it’s stupid’. The director suggests that the violence of the film isn’t wholly physical: much of it is psychological, and the ‘twisted minds’ within the film are ‘kindergarten stuff compared to the twisted minds that walk among us in every part of the world’ – for example, Mastorakis says, the Taliban. ‘The Films of Nico Mastorakis’. This stupendously indepth look at Mastorakis’ filmmaking career is broken down into four parts: -- ‘Part 1: From the Beginning to Skyhigh’ (58:28). -- ‘Part 2: From Zero Boys to Terminal Exposure’ (23:29). -- ‘Part 3: Nightmare at Noon’ (35:44). -- ‘Part 4: And Final’ (40:46). Alternate Opening Titles: - ‘Island of Perversion’ (0:50), and ‘Devils in Mykonos’ (1:08). Like the film’s opening titles, these alternate titles sequences have been recreated from undisclosed ‘reference materials’. Island Sounds (with a ‘Play All’ option): - ‘Do You Love Me Like I Love You?’ (2:27). - ‘Destination’ (2:36). - ‘Melodica Theme (I)’ (2:07). - ‘Can You Call It Love?’ (2:52). - ‘Action Theme (percussion)’ (14:04). These are cuts from the film’s soundtrack, allowing the listener to savour the bizarre, ironic lyrics of the songs featured within the film. The film’s trailer (3:05). Nico Mastorakis: Trailer Reel (34:15). This is a compilation of trailers for Mastorakis’ other films. A DVD copy is also included.

Packaging

The discs are housed in an Amaray case with the option of reversing the sleeve art (on the reverse is the artwork associated with the 1982 UK VHS release). Included within the case is a handsomely illustrated booklet with new writing on the film and details about the restoration.

Overall

Given the prevalence of zealotry and intolerance in today’s world, Island of Death still feels remarkably ‘fresh’, if one can look past the garish 1970s fashions and recognise the rich vein of black humour that runs throughout the picture. The film arguably works best if you approach it as a comic book on screen: its outrageous sense of excess is part of its satirical arsenal. Despite Mastorakis’ suggestion that Island of Death is nothing more than a ‘recipe movie’, it’s quite obvious that the film has a very clearly-defined point-of-view: as a black comedy and a satirical depiction of a form of fanaticism that, it seems, will perennially blight the human race, the film works very well. However, it’s certainly an acquired taste. Given the prevalence of zealotry and intolerance in today’s world, Island of Death still feels remarkably ‘fresh’, if one can look past the garish 1970s fashions and recognise the rich vein of black humour that runs throughout the picture. The film arguably works best if you approach it as a comic book on screen: its outrageous sense of excess is part of its satirical arsenal. Despite Mastorakis’ suggestion that Island of Death is nothing more than a ‘recipe movie’, it’s quite obvious that the film has a very clearly-defined point-of-view: as a black comedy and a satirical depiction of a form of fanaticism that, it seems, will perennially blight the human race, the film works very well. However, it’s certainly an acquired taste.

This Blu-ray release is very impressive, though there’s some wear and tear to the audio track and the film’s fifth reel suffered extensive damage that the restoration on this disc has gone some way towards remedying. The new presentation certainly highlights the strengths of the film’s photography. It’s a shame that the commentary from Arrow’s previous DVD release hasn’t been ported over to this Blu-ray disc, but regardless there’s a wealth of contextual material on offer here which is worth the price of admission alone: the huge documentary about Mastorakis’ career is fascinating in its level of detail, for example. Fans of the film will find this Blu-ray release a worthy upgrade over the previous DVDs

|

|||||

|