|

|

Deadlier Than the Male (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th June 2015). |

|

The Film

Deadlier Than the Male (Ralph Thomas, 1967) Deadlier Than the Male (Ralph Thomas, 1967)

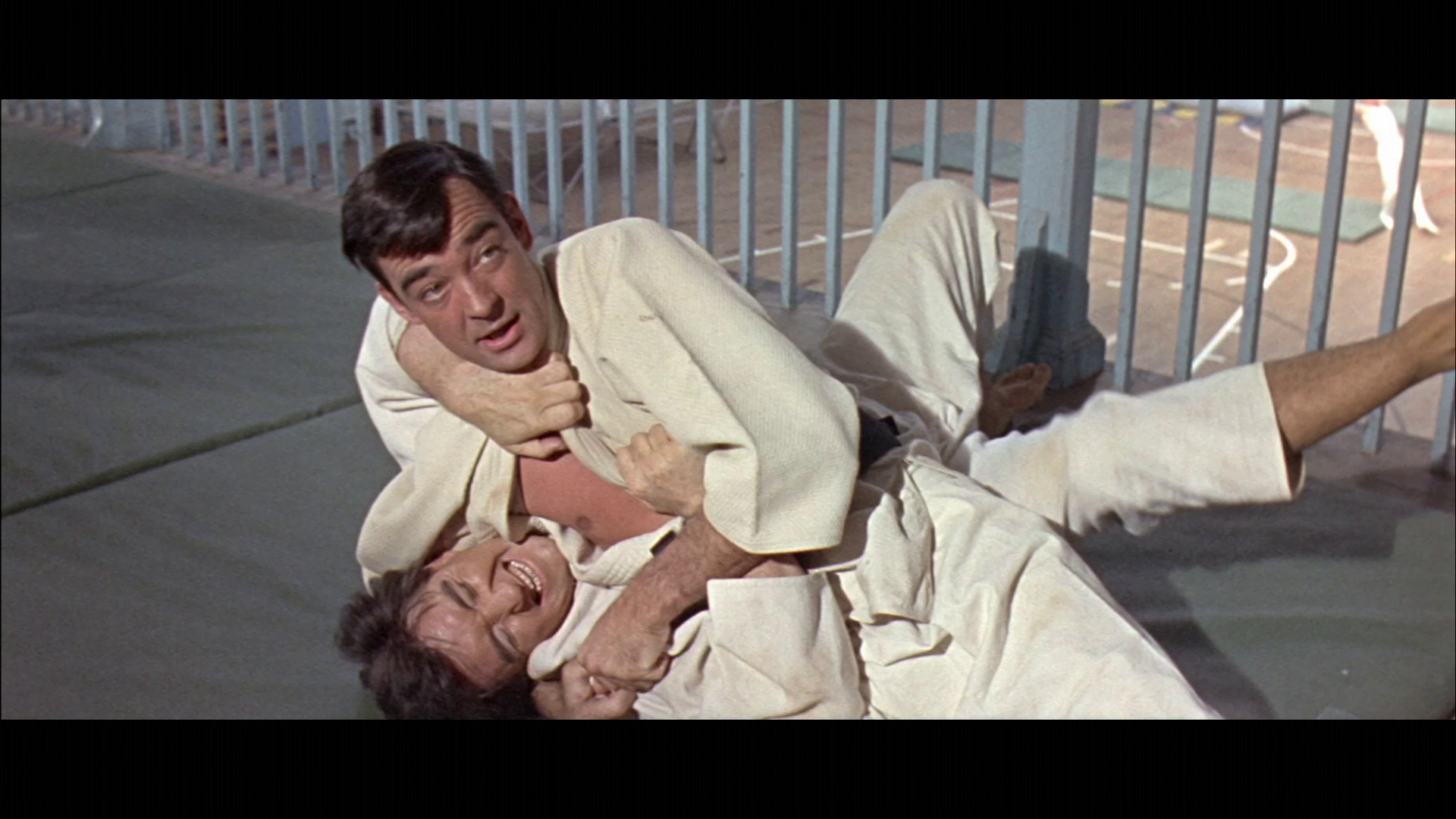

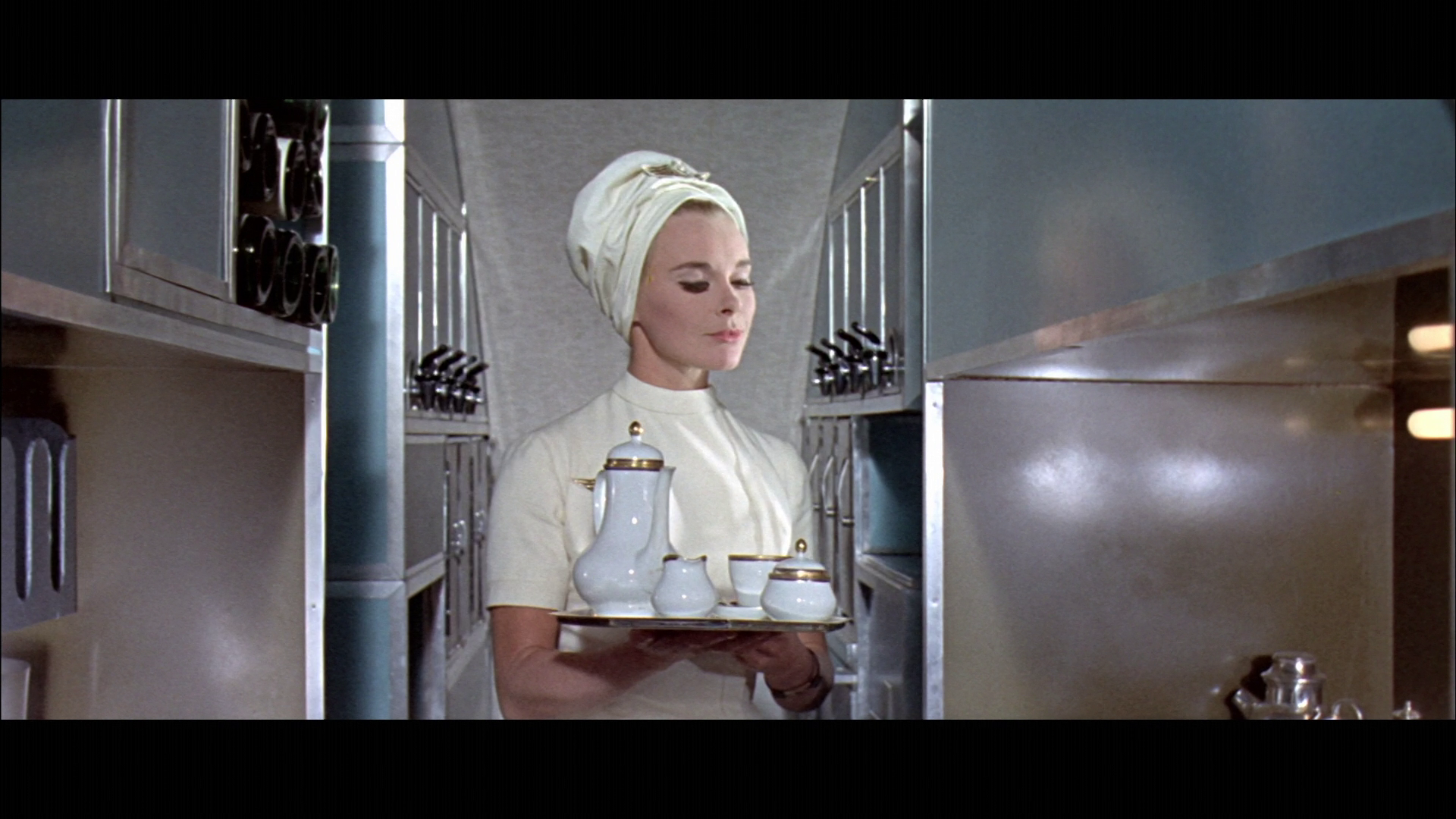

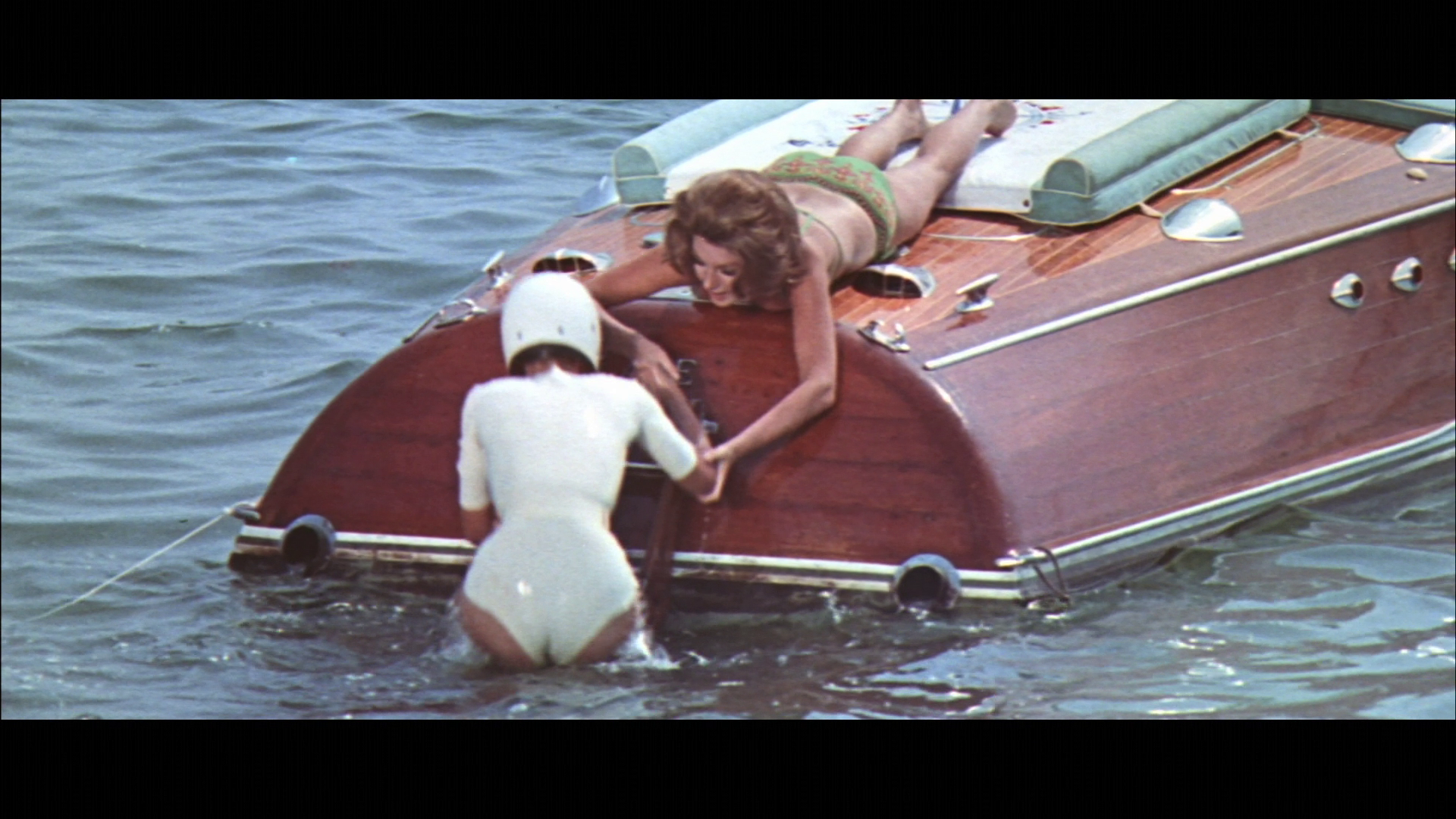

The character of ‘Bulldog’ Drummond was created by Herman Cyril McNeile, writing under his nom-de-plume ‘Sapper’. The first of the Bulldog Drummond books (Bull-Dog Drummond) was published in 1920, and was adapted for the big screen in 1922. From that point onwards, the Bulldog Drummond films would prove popular with filmmakers during the 1930s and 1940s, though the character would ‘rest’ from screen appearances between 1951’s Calling Bulldog Drummond and the production of Ralph Thomas’ Deadlier Than the Male (1967), which featured Richard Johnson (who sadly passed away the weekend before this Blu-ray was released) as Drummond. Filmed under the working title of ‘Female of the Species’, Deadlier Than the Male - and its sequel Some Girls Do (1969, also starring Johnson as Bulldog Drummond) – bears little resemblance to Sapper’s creation, with both films taking a greater part of their inspiration from the Sean Connery-starring James Bond films of the 1960s. These two pictures were part of a wave of outrageous spy thrillers made during that era which featured exotic locations and beautiful Euro starlets (in the case of Deadlier Than the Male, Elke Sommer and Sylva Koscina, who would also star together in Giorgio Bianchi’s Love the Italian Way, 1960, and Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil, 1973), alongside other films such as Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966) and Gordon Douglas’ In Like Flint (1967). (Some Girls Do, the outlandish sequel to Deadlier Than the Male, also features female robot assassins, an undoubted influence on the ‘fembots’ in Jay Roach’s Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, 1997.) Deadlier Than the Male begins with Eckman (Elke Sommer) aboard an aeroplane belonging to Keller (Dervis Ward), an oil company executive. She lights his cigar, which unbeknownst to Keller contains a .22 bullet that fires through his mouth and out the back of his head. After performing this act of assassination, Eckman parachutes from the plane, aboard which she has left a bomb which explodes, and lands in the sea where she is picked up by a speedboat piloted by her associate Penelope (Sylva Koscina). Shortly afterwards, Eckman and Penelope, clad in snorkeling gear and carrying harpoon guns, exit the sea on a Mediterranean island and execute Wyngarde (John Stone).  Back in London, insurance underwriter Hugh ‘Bulldog’ Drummond’s (Richard Johnson) judo practice is interrupted when he is called to a meeting with Sir John Bledlow (Laurence Naismith), the head of the oil company for which Keller worked. Keller’s death is described by Sir John as a ‘nasty business’ but nevertheless works in the company’s favour by eliminating the chief objector to a merger which will grant the company access to a particularly lucrative Middle Eastern oil field. A friend of Drummond’s, Wyngarde also worked for Sir John’s company, conducting what Sir John describes as ‘exploratory work on oil fields’. Sir John confides in Drummond that he believes Wyngarde was executed because he knew something about Keller’s death. Back in London, insurance underwriter Hugh ‘Bulldog’ Drummond’s (Richard Johnson) judo practice is interrupted when he is called to a meeting with Sir John Bledlow (Laurence Naismith), the head of the oil company for which Keller worked. Keller’s death is described by Sir John as a ‘nasty business’ but nevertheless works in the company’s favour by eliminating the chief objector to a merger which will grant the company access to a particularly lucrative Middle Eastern oil field. A friend of Drummond’s, Wyngarde also worked for Sir John’s company, conducting what Sir John describes as ‘exploratory work on oil fields’. Sir John confides in Drummond that he believes Wyngarde was executed because he knew something about Keller’s death.

Keller’s death means that the merger can go ahead without costing Sir John’s company money. However, Sir John and Weston (Nigel Green) still wish to pay the money (a million pounds) to the other company involved in the merger: ‘Because we have a contract’, Sir John offers as an explanation, ‘And when I make a contract, I stick to it’. Sir John’s wish is frustrated by a member of the board of directors, Bridgenorth (Leonard Rossiter). Bridgenorth is soon eliminated by Eckman, who seduces Bridgenorth before subduing him with a paralyzing agent and, with the aid of Penelope, throwing him out of the window of his penthouse flat. (‘Well, I’ve had men fall for me before, but never like this’, Eckman declares as Bridgenorth hurtles to the concrete below.) A visit from Wyngarde’s servant Carloggio (George Pastell) provides Drummond with a small piece of evidence from Wyngarde’s murder: a fragment of an audio tape recording. This piece of evidence costs Carloggio his life: he is assassinated by Eckman and Penelope as he leaves Drummond’s flat.  Drummond and his American nephew Rob (Steve Carlson), who is holidaying in London, are drawn further into the mystery when an attempt is made on Drummond’s life with the same deadly cigars that killed Keller. Determined to get to the bottom of the mystery, Drummond visits Boxer (Lee Montague), a professional criminal and a former military colleague of Drummond’s: whilst serving in the Korean war, Drummond and Boxer were held as prisoners of war and, working together, escaped from their captors. Drummond asks Boxer to use his criminal contacts to help him acquire information that might lead to the killers of Keller and Wyngarde. Drummond and his American nephew Rob (Steve Carlson), who is holidaying in London, are drawn further into the mystery when an attempt is made on Drummond’s life with the same deadly cigars that killed Keller. Determined to get to the bottom of the mystery, Drummond visits Boxer (Lee Montague), a professional criminal and a former military colleague of Drummond’s: whilst serving in the Korean war, Drummond and Boxer were held as prisoners of war and, working together, escaped from their captors. Drummond asks Boxer to use his criminal contacts to help him acquire information that might lead to the killers of Keller and Wyngarde.

After Weston appears to be killed by a bomb that explodes in his office, Drummond and Rob travel to the Mediterranean island where Wyngarde was murdered. There, they are met by King Fedra (Zia Mohyeddin), a university friend of Rob’s and, incidentally, the monarch of Akmata, where the contested oil field is located. Fedra tells Drummond that the oil companies will get to the Akmata oil fields ‘over my dead body’, and Drummond informs him that, given the murders that have already taken place in relation to the merger, that may be a distinct possibility: ‘We Middle Eastern monarchs seem to have a pretty precarious existence’, Fedra jokes. A castle is situated on the island, and Drummond is called to it to meet with Carl Petersen – who is really Weston. ‘I would have been here sooner, but I stayed in London for your cremation’, Drummond quips upon meeting Petersen. Petersen, it seems, has been training his own private army of glamorous female assassins who work internationally. Petersen is intent on eliminating King Fedra, and in an echo of his experiences during the Korean war, Drummond is faced with the task of escaping from his captors to save the lives of both Fedra and Rob.  The film conforms to some of the salient features of the template established by the Bond films of the era: beautiful women, exotic locations, the reliance on one-liners. (Sir John tells Drummond that Wyngarde was apparently killed with a harpoon gun whilst skindiving, and in response Drummond declares, ‘Now I know there’s something fishy: He couldn’t swim’.) As in the Bond pictures (for example, Terence Young’s Dr No, 1962), Drummond finds himself enticed into the lair of the villain, where it seems Drummond is to be killed – but only after Petersen has toyed with him and explained his plan in some detail. Petersen also sends Eckman to seduce Drummond, though the purpose of this is unclear (Petersen seems to have a surveillance camera installed in Drummond’s room, so it could be part of a voyeuristic thrill). Drummond resists Eckman’s advances, sending her away, telling her, ‘So you’d better go and tell your boyfriend that though I enjoyed his dinner, I really couldn’t face the dessert’. Eckman slaps him: ‘You are unnatural’, she declares angrily. The film conforms to some of the salient features of the template established by the Bond films of the era: beautiful women, exotic locations, the reliance on one-liners. (Sir John tells Drummond that Wyngarde was apparently killed with a harpoon gun whilst skindiving, and in response Drummond declares, ‘Now I know there’s something fishy: He couldn’t swim’.) As in the Bond pictures (for example, Terence Young’s Dr No, 1962), Drummond finds himself enticed into the lair of the villain, where it seems Drummond is to be killed – but only after Petersen has toyed with him and explained his plan in some detail. Petersen also sends Eckman to seduce Drummond, though the purpose of this is unclear (Petersen seems to have a surveillance camera installed in Drummond’s room, so it could be part of a voyeuristic thrill). Drummond resists Eckman’s advances, sending her away, telling her, ‘So you’d better go and tell your boyfriend that though I enjoyed his dinner, I really couldn’t face the dessert’. Eckman slaps him: ‘You are unnatural’, she declares angrily.

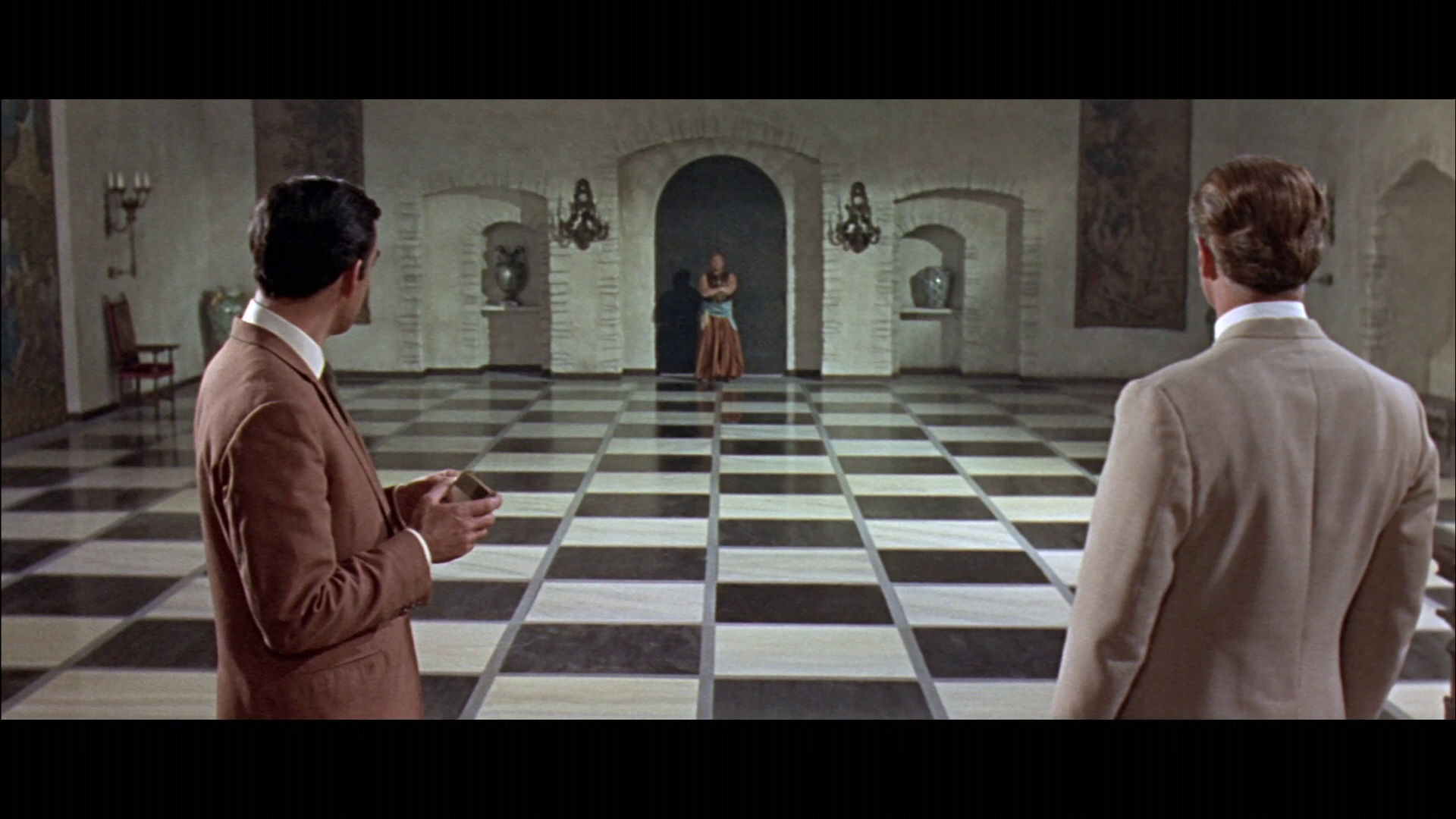

There’s a subtle critique of the modern-day corporate mentality and the lack of humanity within the culture of business, where profit is paramount. Reflecting on Keller’s death, Sir John tells Drummond, ‘It’s a sick world, Hugh. Keller’s dead. And because of it, do you know what I’ll find around the […] board table this morning? Lots of happy, smiling faces’. Meanwhile, Petersen’s deadly female assassins are, it seems, employed solely by big business for the purposes of committing murders with the aim of devaluing their rivals’ stock or, as in the case of the murders of Keller and Wyngarde, eliminating those who may act as barriers to a company’s objectives. These are corporate assassins rather than political assassins. ‘There’s no better way of devaluing stock than to have the president of the organisation blow his brains out’, Petersen tells Drummond matter-of-factly, expanding on the ‘mission statement’ (to use present-day parlance) of his organisation: ‘You see, Drummond, in big business huge sums of money depend on the ability of one man. Competitors try every way they know to bring that man down. They employ complicated and expensive methods: stock deals, market rigging, price cutting. It never entered anyone’s head that there was a far simpler way of getting what one wanted [….] My method is simplicity itself: if a man stands in your way, dispose of that man’. The corporate approach has, the film suggests, even spread into the world of criminal endeavours. Boxer, Drummond’s friend from the Korean war, is apparently a member of an organised crime syndicate with apparently global connections, and which makes full use of modern technology to achieve its aims. When Drummond approaches Boxer for information, Boxer makes a telephone call, telling Drummond, ‘We [the members of his crime syndicate, presumably] keep up to date records on everything. Well, we have to. Chicago, New York, Beirut, Hong Kong. I’ve even got my own private hotwire to Moscow. And what we haven’t got on file, we can get by teletype, the same day’.  Deadlier Than the Male makes some nods towards the self-reflexivity of films like Losey’s Modesty Blaise. At one point, as if to pre-empt the audience’s potential criticisms of the absurdity of Petersen’s troupe of female assassins and his theatrical use of a castle on a Mediterranean island as a base of operations, Drummond goads Petersen by telling him, ‘It is rather comical, isn’t it? The girls, the castle, [nods to Petersen’s bodyguard, Karl] Fu Manchu over there… even you [….] The whole thing’s so theatrical, isn’t it?’ This theatricality is carried over into the climax, which sees Drummond and Petersen facing off against one another amongst a huge computer-controlled chess board populated by life-sized chess pieces, in a sequence which wouldn’t seem out of place in an episode of The Avengers (1961-9). Deadlier Than the Male makes some nods towards the self-reflexivity of films like Losey’s Modesty Blaise. At one point, as if to pre-empt the audience’s potential criticisms of the absurdity of Petersen’s troupe of female assassins and his theatrical use of a castle on a Mediterranean island as a base of operations, Drummond goads Petersen by telling him, ‘It is rather comical, isn’t it? The girls, the castle, [nods to Petersen’s bodyguard, Karl] Fu Manchu over there… even you [….] The whole thing’s so theatrical, isn’t it?’ This theatricality is carried over into the climax, which sees Drummond and Petersen facing off against one another amongst a huge computer-controlled chess board populated by life-sized chess pieces, in a sequence which wouldn’t seem out of place in an episode of The Avengers (1961-9).

There is also a suprising level of sadism on display in the film. Eckman’s assassination of Keller is punctuated by a close-up of the grisly exit wound the .22 bullet leaves at the base of his skull. (The use of the cigars containing .22 bullets which are fired out of the stem when they are lit brings to mind the CIA’s supposed attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro with an exploding cigar in 1966.) Whilst leaving Boxer’s home, Drummond is attacked by a group of thugs in a parking garage, and he uses his car to pin one of these men (George Sewell) against a wall before interrogating him. Later, Penelope captures Rob and ties him up with rope, apparently taking delight in burning his naked torso with cigarettes. (Drummond rescues Rob and, referring to the topes with which he has been bound, declares, ‘I didn’t knew you went in for this kind of thing, Rob [….] Oh, that’s a nasty burn. You really ought to learn how to control your girlfriends, you know’.)  The film provoked some debate between the BBFC and Sydney Box, one of the film’s producers: the BBFC took umbrage at the film’s depiction of beautiful women as assassins, being ‘not entirely happy about beautiful, sexy girls committing a series of ruthless murders’ and arguing that ‘[i]t would be easier from our point of view if Petersen employed some male thugs, and used his beautiful girls for more decorative and less homicidal purposes’ (BBFC letter to Sydney Box, quoted in Spicer, 2006: 197). For the BBFC, the script that was submitted for their consideration contained too much ‘emphasis on promiscuity, which is largely based on nymphomania’ and was ‘permeated with sadism’ (BBFC letter, quoted in ibid.). The BBFC also suggested that the sex and violence within the picture should be presented ‘lightly and unrealistically’ if the producers wished to ensure that the film received an ‘A’ certificate, and the picture was ‘[n]ot a film which, in our view, should be seen by young teen-agers (girls particularly)’ (BBFC letter, quoted in ibid.). (The sexist sentiment of the BBFC’s assertions is difficult to ignore.) Ultimately, the film was given an ‘X’ certificate (although with some cuts made by the BBFC), which the producers accepted rather than make the more extensive cuts that would have been required to ensure an ‘A’ classification. The film provoked some debate between the BBFC and Sydney Box, one of the film’s producers: the BBFC took umbrage at the film’s depiction of beautiful women as assassins, being ‘not entirely happy about beautiful, sexy girls committing a series of ruthless murders’ and arguing that ‘[i]t would be easier from our point of view if Petersen employed some male thugs, and used his beautiful girls for more decorative and less homicidal purposes’ (BBFC letter to Sydney Box, quoted in Spicer, 2006: 197). For the BBFC, the script that was submitted for their consideration contained too much ‘emphasis on promiscuity, which is largely based on nymphomania’ and was ‘permeated with sadism’ (BBFC letter, quoted in ibid.). The BBFC also suggested that the sex and violence within the picture should be presented ‘lightly and unrealistically’ if the producers wished to ensure that the film received an ‘A’ certificate, and the picture was ‘[n]ot a film which, in our view, should be seen by young teen-agers (girls particularly)’ (BBFC letter, quoted in ibid.). (The sexist sentiment of the BBFC’s assertions is difficult to ignore.) Ultimately, the film was given an ‘X’ certificate (although with some cuts made by the BBFC), which the producers accepted rather than make the more extensive cuts that would have been required to ensure an ‘A’ classification.

The version of the film on this disc runs 97:36 mins and, as with the film’s previous DVD releases, is presumably the British ‘X’ version as cut by the BBFC in 1967, which trims the sequence in which Penelope tortures Rob by burning him with a cigarette, and also loses a rear nude shot of Penelope.

Video

The film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and takes up approximately 16Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film was shot in Techniscope, the cost-saving 2-perf format. Techniscope achieved a widescreen ratio of approximately 2.35:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. This decreased production costs (halving the amount of film stock used and reducing the need to hire expensive anamorphic lenses), though it is said that the lab costs of films shot in Techniscope were higher than those of films shot using more conventional anamorphic widescreen processes – one of the reasons why Techniscope became increasingly less popular during the late-1970s. The film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and takes up approximately 16Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film was shot in Techniscope, the cost-saving 2-perf format. Techniscope achieved a widescreen ratio of approximately 2.35:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. This decreased production costs (halving the amount of film stock used and reducing the need to hire expensive anamorphic lenses), though it is said that the lab costs of films shot in Techniscope were higher than those of films shot using more conventional anamorphic widescreen processes – one of the reasons why Techniscope became increasingly less popular during the late-1970s.

Release prints were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. However, during the 1960s, when Techniscope films were blown-up using dye transfer processes in use by Technicolor Italia, it was possible to skip the dupe negative step and ‘save’ a generation, thus resulting in an image with a finer grain structure and deeper blacks (characteristics of films produced using dye transfer processes generally, not just those shot in Techniscope). In the 1970s, for economic reasons dye transfer printing for films shot in Techniscope was replaced with the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative (and an additional ‘generation’ for the material). This resulted in a more coarse grain structure to Techniscope films released in the 1970s and beyond. The film is here presented in an aspect ratio of 2.35:1, which would seem to be its intended aspect ratio. Some minor damage is present from the start of the film (white flecks and specks). Contrast is good, and the image contains a fairly good amount of detail, although there’s a softness ot the photography which doesn’t seem to be a product of the lenses used to shoot the film, and the presentation lacks the depth of other Techniscope films that have been released on Blu-ray: Network’s own Blu-ray release of The IPCRESS File, also shot in Techniscope, is perhaps worth considering as a point of comparison (see our review of that disc, with some large screengrabs from it, here). Some film grain is present but it seems unnaturally subdued – perhaps as a result of digital noise reduction software or simply as a consequence of being ‘crushed’ by the encode. Certainly, the presentation doesn’t have the slightly more pronounced grain structure of most tip-top presentations of films shot in Techniscope (such as Network’s The IPCRESS File, the Italian RHV Blu-ray release of Sergio Leone’s Fistful of Dollars, 1964, or Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Lucio Fulci’s Zombie Flesh Eaters, 1979), whether sourced from the 2-perf negative or a 4-perf blow-up. It’s a pleasant presentation of the film, unarguably an improvement over the DVDs that are available. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is vivid and clear, with good range evident within it. Dialogue is clear throughout. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes a number of vintage interviews from the time of the film’s production. Members of the cast are interviewed separately, on location, by a television crew. Interviewees include Richard Johnson (5:02), Elke Sommer (5:12), Sylva Koscina (3:43), Nigel Green (5:51), and Steve Carlson (4:42). Also included are two location reports (15:16 and 14:21), again recorded by a television crew. These are accompanied by a trailer (3:01) and a series of image galleries: behind the scenes (8:17), portraits of the cast and crew (6:47), production stills (16:11), and a final gallery of promotional artwork (2:47).

Overall

A light, entertaining film, Deadlier Than the Male is very much in the mold established by the Bond pictures and has little in common with Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond stories. It’s undoubtedly a product of its era, and has a self-reflexivity and a subtle critique of the corporate mentality that is to be admired. Its depiction of a team of beautiful female assassins is depicted in a very ironic, tongue-in-cheek manner. However, what is perhaps surprising is the level of sadism on display (Sylva Koscina’s character is particularly cruel). A light, entertaining film, Deadlier Than the Male is very much in the mold established by the Bond pictures and has little in common with Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond stories. It’s undoubtedly a product of its era, and has a self-reflexivity and a subtle critique of the corporate mentality that is to be admired. Its depiction of a team of beautiful female assassins is depicted in a very ironic, tongue-in-cheek manner. However, what is perhaps surprising is the level of sadism on display (Sylva Koscina’s character is particularly cruel).

This Blu-ray release contains a pretty good presentation of the film that is certainly an improvement over the various DVD releases, but not amongst the top tier of Blu-ray presentations of films shot in the Techniscope format. A good range of vintage contextual material rounds out the package. References: Slifkin, Irv, 2004: VideoHound’s Groovy Movies: Far-Out Films of the Psychedelic Era. Missouri: Visible Ink Press Spicer, Andrew, 2006: British Film Makers: Sydney Box. Manchester University Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|