|

|

The Film

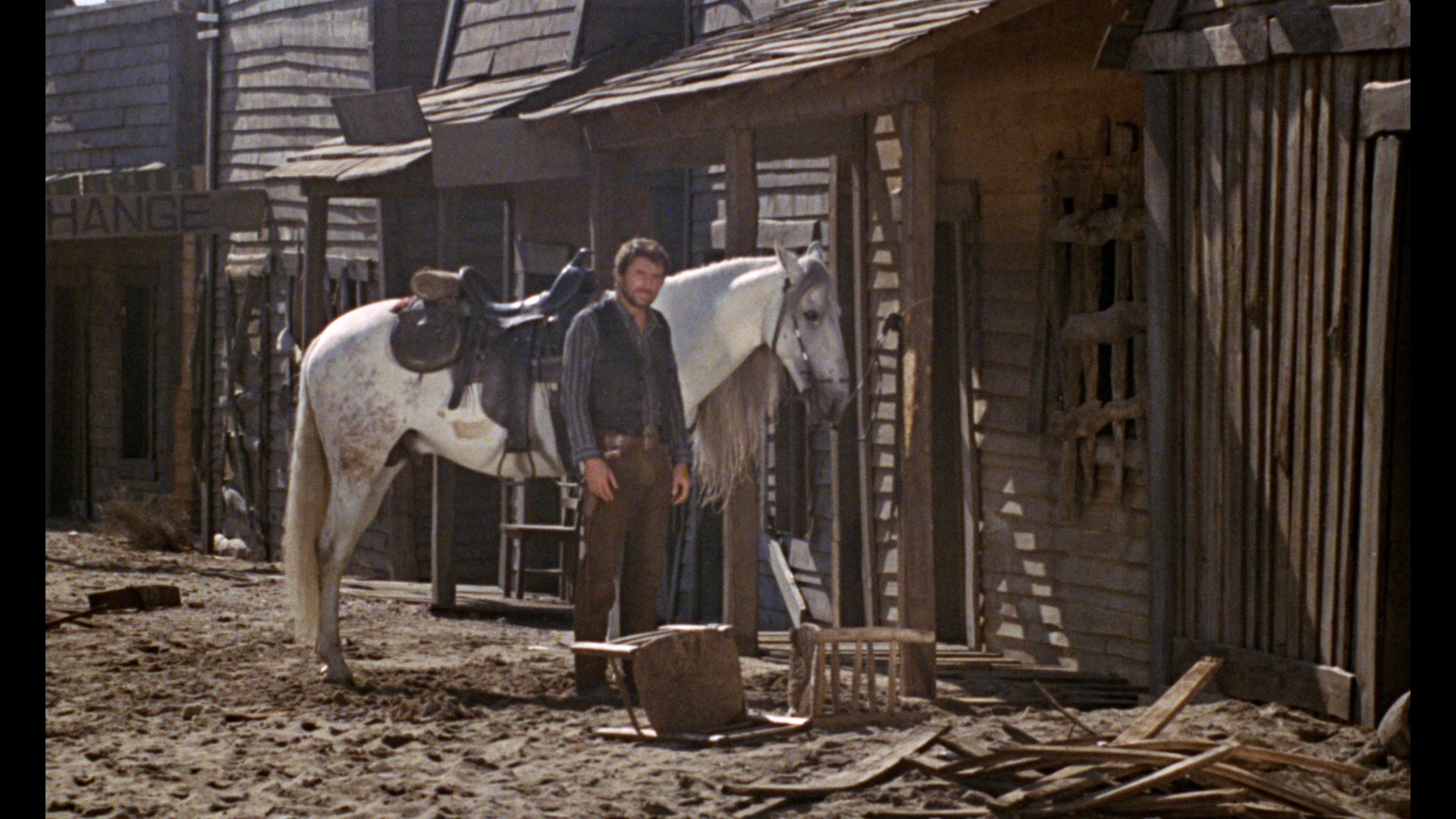

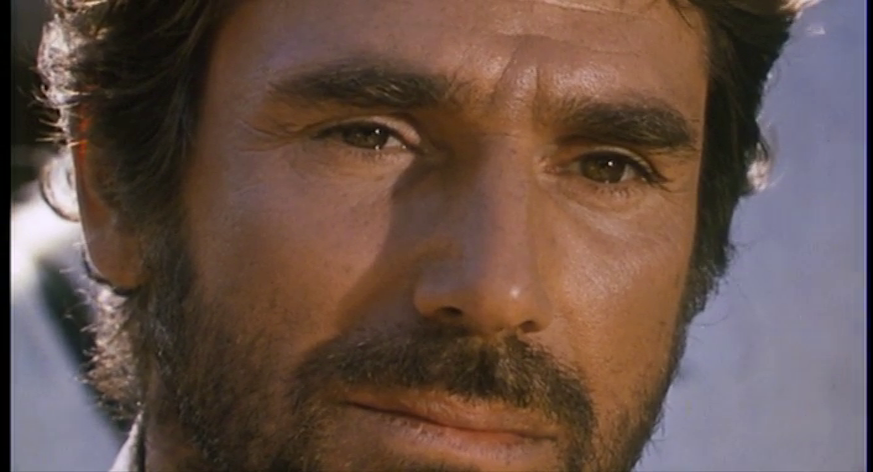

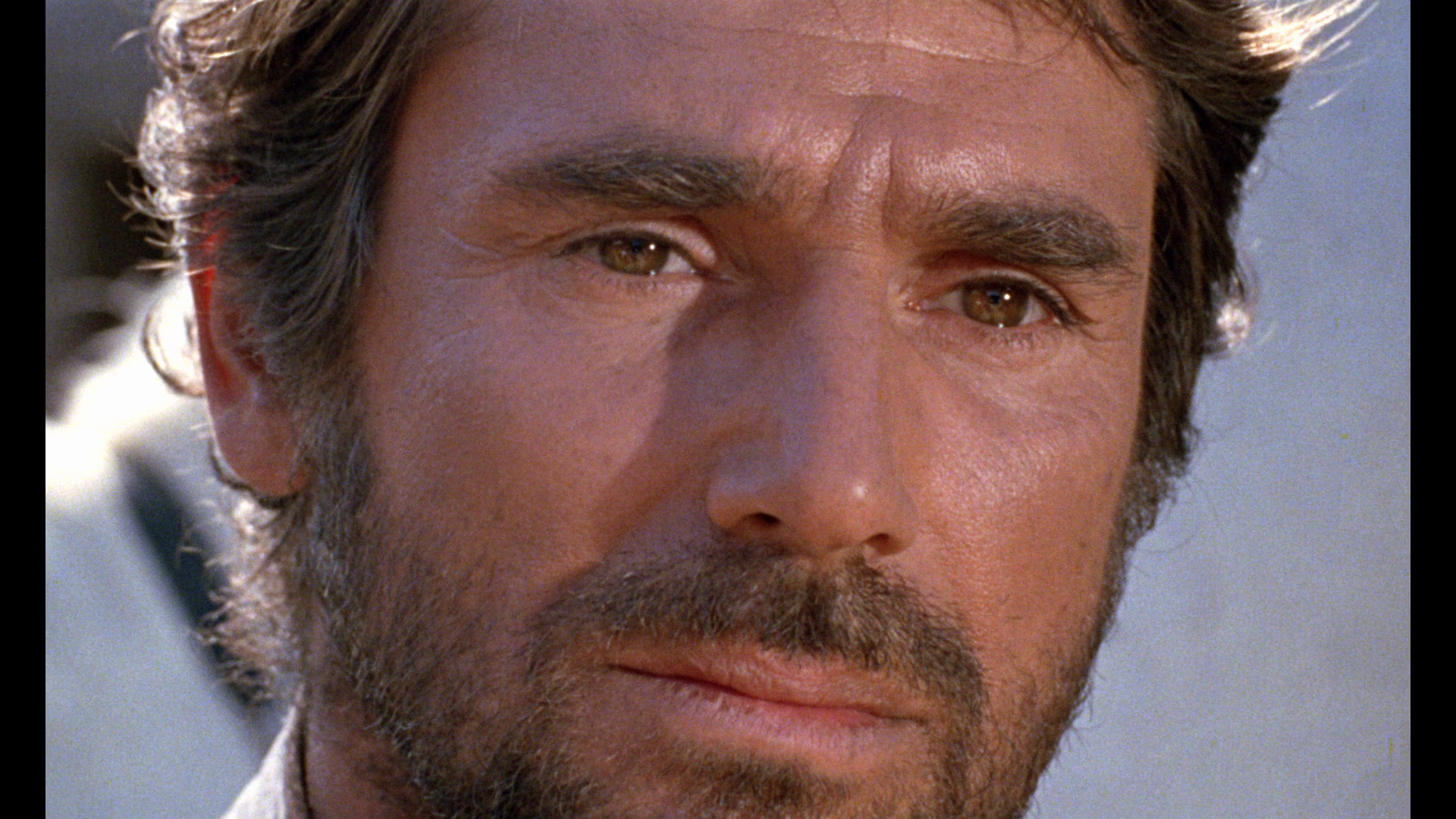

Cemetery Without Crosses (Robert Hossein, 1969) Cemetery Without Crosses (Robert Hossein, 1969)

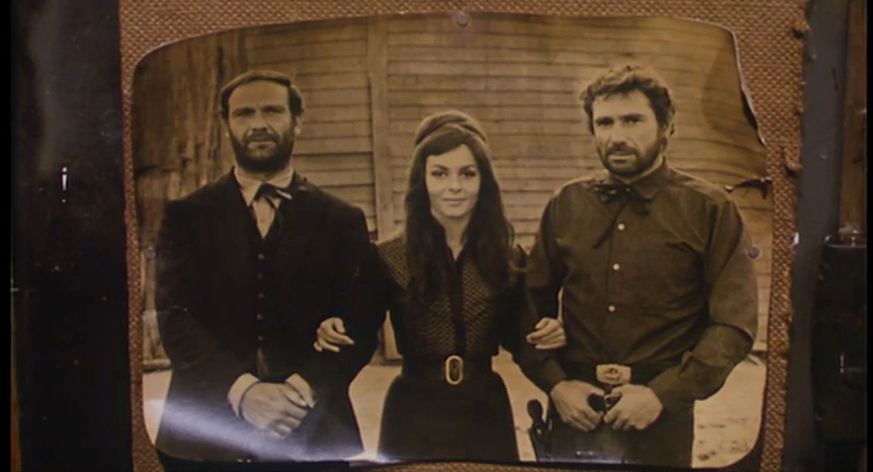

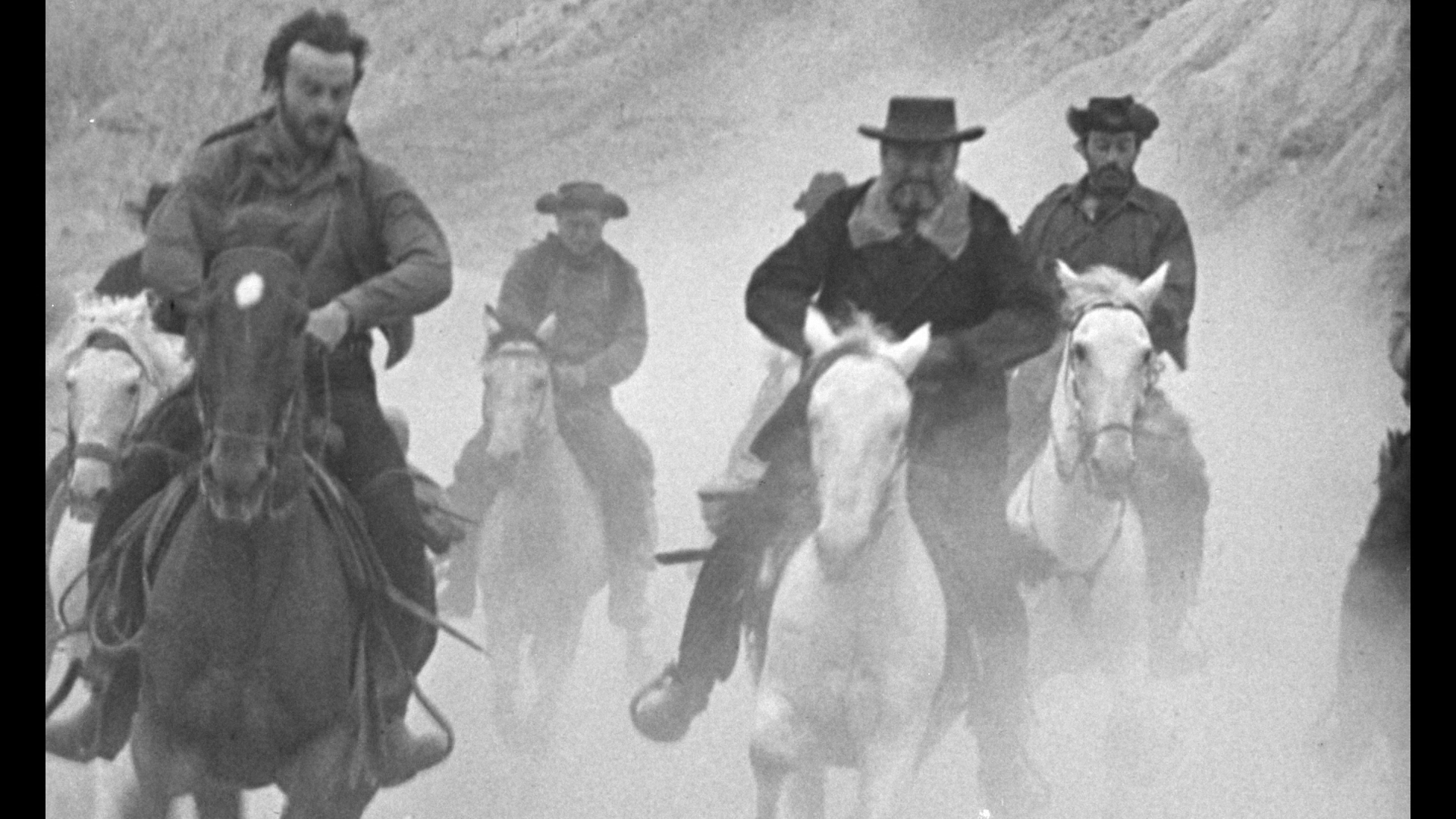

AKA Une corde… un Colt/The Rope and the Colt, Cimitero senza croci Directed by French actor/director Robert Hossein, Cemetery Without Crosses (1969) is a tribute to the westerns all’italiana (Italian-style Westerns) of Sergio Leone. It’s the only Western Hossein directed, though his 1961 film Le goût de la violence (The Taste of Violence), about the Mexican Revolution, prefigures some of the later Italian ‘Zapata’ Westerns set during the Mexican Revolution (such as Damiano Damiani’s Quién sabe?/A Bullet for the General, 1966; and Sergio Corbucci’s Companeros, 1970) and has a similarly melancholy ‘flavour’ to Cemetery Without Crosses. Focusing on the conflict between two families, Cemetery Without Crosses opens with a monochrome or sepia-tinted sequence (depending on whether you are watching French or Italian prints) depicting the men of the Rogers family, led by patriarch Will Rogers (Daniele Vargas), pursuing the three Caine brothers – Ben (Benito Stefanelli), Thomas (Guido Lollobridgida) and Eli (Michel Lemoine) – to the homestead where Ben lives with his wife Maria (Michèle Mercier). Thomas and Eli manage to escape into the hills, but Ben, who seems to be wounded, falls from his horse and cries out for Maria. Rogers and his men lynch Ben in front of Maria, hanging him. After Rogers and his men have left, Thomas and Eli come down from the hills and seek refuge in Ben and Maria’s home. They carry with them sacks filled with stolen gold. They give Ben’s share to Maria, who rides into a ghost town to speak with former gunslinger Manuel (Robert Hossein). Maria asks Manuel for help. ‘Why should I?’, he asks. ‘You’re the only one who can stand up to the Rogers’, she tells him.  Manuel rides into a nearby town and finds some of the Rogers clan in dispute with the Vallee brothers. Manuel defends one of the Rogers by shooting dead one of the Vallees, thus currying favour with the Rogers. Manuel is thrown into the cells behind the sheriff’s office but he is freed in the morning by members of the Rogers clan, who tell the sheriff, ‘He [Manuel] works for us. Let him out. We’ll work the whole thing out’. Manuel returns with the Rogers to their family’s ranch, where Will Rogers offers Manuel a job. There, Manuel meets Rogers’ pretty daughter Johanna (Anne-Marie Balin). Manuel rides into a nearby town and finds some of the Rogers clan in dispute with the Vallee brothers. Manuel defends one of the Rogers by shooting dead one of the Vallees, thus currying favour with the Rogers. Manuel is thrown into the cells behind the sheriff’s office but he is freed in the morning by members of the Rogers clan, who tell the sheriff, ‘He [Manuel] works for us. Let him out. We’ll work the whole thing out’. Manuel returns with the Rogers to their family’s ranch, where Will Rogers offers Manuel a job. There, Manuel meets Rogers’ pretty daughter Johanna (Anne-Marie Balin).

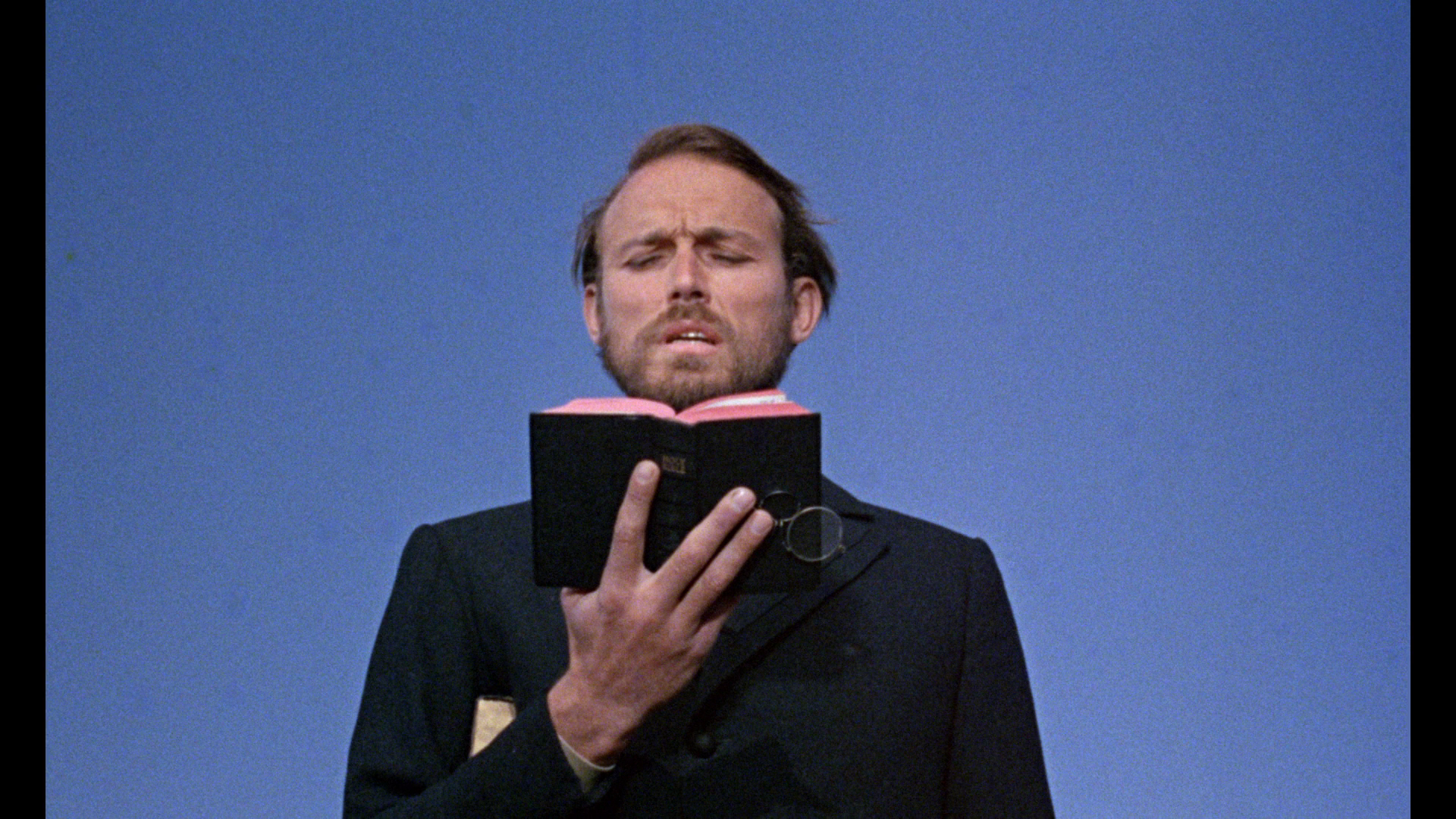

At night, Manuel frees the Rogers’ horses. As the Rogers are rounding up their steeds, Manuel abducts Johanna and takes her back to the Caines, who are hiding in Manuel’s casino. There, Thomas and Eli subject Johanna to a sexual assault whilst Manuel and Maria wait impotently in the street outside. Following this, Maria visits Will Rogers, telling him that ‘your money won’t be able to ransom her [Johanna]. I want much less and much more’: she wants Ben to be disinterred from his makeshift grave and buried in the town cemetery, with Will Rogers and his sons as Ben’s pallbearers. Maria gets what she wished for: Ben is given a proper funeral, and the Rogers attend it. However, Thomas and Eli have designs of their own, and seemingly unbeknownst to Maria they approach Will Rogers and tell him that he will have to hand over twenty thousand dollars for the safe return of his daughter. Will Rogers is of course displeased by these underhand tactics and seeks revenge on the Caines – and Manuel. The opening sequence in which the Rogers lynch Ben Caine in front of his wife Maria marks the Rogers clan as cruel and sadistic. Ben, who has fallen from his horse, lays on the floor, his wife by his side; he reaches for his gun, but is shot in the hand by one of the Rogers. They grab him and tie a rope around his neck, throwing it over a makeshift gibbet. They sit him on his horse and whip the creature out from under him as Maria watches on; she is held back by two of the Rogers, one of their hands clasped over her mouth to prevent her from screaming, but her wide open eyes betray the horror she is experiencing at witnessing the murder of her husband.  Soon after this horrendous spectacle, the callousness of Ben’s brothers becomes apparent; conversely, as the narrative progresses the Rogers family becomes increasingly sympathetic. Thomas and Eli come down from the hills, after the Rogers have left, and refuse to help Maria bury her dead husband, passing her as she digs the grave and watching passively as she toils away. Later, the Caines foil an ambush at Ben and Maria’s home; as they do so, Hossein cuts to Maria unceremoniously cleaving the head off a skinned rabbit. The association of poverty and food is followed by an ironic cut to the Rogers’ ranch, where the Rogers family are seated around a huge dining table. Here, the joviality and warmth of the Rogers is placed in juxtaposition with the mercenary behaviour and dour coldness of Thomas and Eli Caine. Will Rogers presides over the meal, saying grace; the men then eat their food in a civilised manner. As the meal progresses, Hossein presents us with close-ups of the men as they look at Manuel. Manuel becomes visibly uneasy. It seems that he expects the Rogers to attack him. However, it’s all part of a good-natured practical joke: like Manuel, we expect the worst and believe that Manuel is about to be attacked, but the men are simply waiting for him to open the jar of mustard – in which they’ve placed a jack-in-the-box. Soon after this horrendous spectacle, the callousness of Ben’s brothers becomes apparent; conversely, as the narrative progresses the Rogers family becomes increasingly sympathetic. Thomas and Eli come down from the hills, after the Rogers have left, and refuse to help Maria bury her dead husband, passing her as she digs the grave and watching passively as she toils away. Later, the Caines foil an ambush at Ben and Maria’s home; as they do so, Hossein cuts to Maria unceremoniously cleaving the head off a skinned rabbit. The association of poverty and food is followed by an ironic cut to the Rogers’ ranch, where the Rogers family are seated around a huge dining table. Here, the joviality and warmth of the Rogers is placed in juxtaposition with the mercenary behaviour and dour coldness of Thomas and Eli Caine. Will Rogers presides over the meal, saying grace; the men then eat their food in a civilised manner. As the meal progresses, Hossein presents us with close-ups of the men as they look at Manuel. Manuel becomes visibly uneasy. It seems that he expects the Rogers to attack him. However, it’s all part of a good-natured practical joke: like Manuel, we expect the worst and believe that Manuel is about to be attacked, but the men are simply waiting for him to open the jar of mustard – in which they’ve placed a jack-in-the-box.

The sadism of the Caines is underscored when Manuel returns to them with Johanna. The Caines take Johanna to an upstairs room; aware of what is about to happen, Manuel exits the building, wanting nothing to do with it. As he and Maria exchange glances in the street outside, they hear Johanna’s cries as she is sexually assaulted by Thomas and Eli. Manuel is visibly disgusted by what is taking place but glances at Maria as if to remind her that this is what her desire for vengeance has wrought. The sequence is in many ways the turning point of the film, where the audience’s sympathy shifts from the Caines to the Rogers. Later, Maria’s desire for revenge is satisfied by the Rogers attendance at Ben’s formal funeral in the town cemetery, but this isn’t enough for Thomas and Eli: they demand twenty thousand dollars from Will Rogers before they will return Johanna. By the end of it all, Maria has tired of vengeance: ‘Let them do what they want, even kill me’, she tells Manuel, ‘I did my duty. That’s all I wanted’. For Thomas and Eli, money is all-important. They fail to intervene in the lynching of Ben, watching passively from the hills, because they’re protecting the sacks of gold they have stolen, and they effectively double-cross Maria by demanding more money from Rogers before they will release Johanna. After they have refused to help Maria bury Ben, Thomas and Eli give to Maria Ben’s share of the stolen gold that they are carrying. However, it’s small compensation for the loss of Ben and Maria doesn’t want these riches: she wants revenge for the murder of her husband. To this end, she rides into the ghost town in which Manuel dwells.  The ghost town is an eerie place, a landscape of the mind. The set was apparently built on shifting sands and therefore disappeared shortly after the film was completed. Manuel’s sense of isolation, his disengagement from the world, is reinforced by his decision to live in an empty, deserted town. He lives in the past, as evidenced by his fascination with his almost derelict casino: he spins the roulette wheel, imagining a time when the casino was filled with life, hearing the voices of the crowd within it. He opens a music box; as its sad chimes sing out, Manuel takes out a single black glove. This black glove is the one he places on his hand just before using his gun (and is an aspect of the mise-en-scène that forms the basis for a wonderful piece of misdirection at the climax of the picture). All of this shows Hossein’s confidence in creating narrative through objects in the mise-en-scène: nothing needs to be said in the dialogue about Manuel’s past or his former glory as a gunfighter, because it’s all there in the photography and Hossein’s performance. (This makes the revelation through dialogue delivered at the end of the film that Manuel and Maria were once lovers, and Maria married Ben only because Manuel was absent, seem all the more redundant.) The glove, representing Manuel’s presumed past as a gunfighter, is indexical of past glories; its importance is conveyed by the fact that Manuel keeps it in a musical jewellery box. Manuel’s retrieval of the glove shows a return to violence – a former gunfighter once again picking up his guns to right a wrong – that underpins many later American revisionist Westerns such as Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992). When he puts the gun on for the first time, he offers a display of his gunfighting prowess by quickdrawing and shooting one of the gas lamps in the casino. The ghost town is an eerie place, a landscape of the mind. The set was apparently built on shifting sands and therefore disappeared shortly after the film was completed. Manuel’s sense of isolation, his disengagement from the world, is reinforced by his decision to live in an empty, deserted town. He lives in the past, as evidenced by his fascination with his almost derelict casino: he spins the roulette wheel, imagining a time when the casino was filled with life, hearing the voices of the crowd within it. He opens a music box; as its sad chimes sing out, Manuel takes out a single black glove. This black glove is the one he places on his hand just before using his gun (and is an aspect of the mise-en-scène that forms the basis for a wonderful piece of misdirection at the climax of the picture). All of this shows Hossein’s confidence in creating narrative through objects in the mise-en-scène: nothing needs to be said in the dialogue about Manuel’s past or his former glory as a gunfighter, because it’s all there in the photography and Hossein’s performance. (This makes the revelation through dialogue delivered at the end of the film that Manuel and Maria were once lovers, and Maria married Ben only because Manuel was absent, seem all the more redundant.) The glove, representing Manuel’s presumed past as a gunfighter, is indexical of past glories; its importance is conveyed by the fact that Manuel keeps it in a musical jewellery box. Manuel’s retrieval of the glove shows a return to violence – a former gunfighter once again picking up his guns to right a wrong – that underpins many later American revisionist Westerns such as Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992). When he puts the gun on for the first time, he offers a display of his gunfighting prowess by quickdrawing and shooting one of the gas lamps in the casino.

Manuel is initially resistant to Maria’s desire for revenge, telling her, ‘I told you you should move out’. ‘Ben didn’t want to leave’, Maria responds, foregrounding the wishes of her dead husband. ‘Don’t complain then’, Manuel offers fatalistically. ‘I’m not complaining: I want revenge’, she asserts. ‘Revenge is a bad seed’, Manuel tells her, ‘It bears bitter fruit’. Manuel is reluctant to be drawn into Maria’s quest for vengeance against the Rogers family, fully aware that revenge leads to a cycle of violence which will have inevitably negative consequences for both perpetrator and victim. It’s a fatalistic worldview, but Manuel is quickly proven to be correct when, hoping to help Maria, he abducts Johanna, who is then subjected to a brutal sexual assault by Thomas and Eli; and this, in turn, provokes a violent response from Will Rogers and his men. Maria’s desire to avenge her husband’s murder provokes a seemingly neverending cycle of cruelty.  Manuel is drawn into the gravitational pull of Maria’s desire for revenge through his unspoken love for her. As noted above, the climax makes it clear that Manuel and Maria are former lovers – and that Maria married Ben Caine in Manuel’s stead. (However, all of this is evident, in subtle gestures, from the first meeting between the pair.) When Maria first approaches Manuel in the ghost town and asks him to act against the Rogers family, he tells her, ‘Now you remember me. It’s too late’. Maria offers Ben’s share of the gold to Manuel. ‘I’m not interested in the money’, he declares, his lack of concern regarding the gold in stark contrast to the mercenary nature of Thomas and Eli Caine. ‘Then do it for me’, she says. ‘What if I don’t?’, Manuel asks. ‘I’ll manage on my own’, she asserts, ‘I know what I’ll have to do’. ‘They’ll kill you’, Manuel informs her. ‘Too bad’, she replies. Of course, Manuel acquiesces to Maria’s desire for vengeance, seemingly because he is aware that Maria doesn’t stand a chance on her own. Manuel is drawn into the gravitational pull of Maria’s desire for revenge through his unspoken love for her. As noted above, the climax makes it clear that Manuel and Maria are former lovers – and that Maria married Ben Caine in Manuel’s stead. (However, all of this is evident, in subtle gestures, from the first meeting between the pair.) When Maria first approaches Manuel in the ghost town and asks him to act against the Rogers family, he tells her, ‘Now you remember me. It’s too late’. Maria offers Ben’s share of the gold to Manuel. ‘I’m not interested in the money’, he declares, his lack of concern regarding the gold in stark contrast to the mercenary nature of Thomas and Eli Caine. ‘Then do it for me’, she says. ‘What if I don’t?’, Manuel asks. ‘I’ll manage on my own’, she asserts, ‘I know what I’ll have to do’. ‘They’ll kill you’, Manuel informs her. ‘Too bad’, she replies. Of course, Manuel acquiesces to Maria’s desire for vengeance, seemingly because he is aware that Maria doesn’t stand a chance on her own.

In the book 10,000 Ways to Die (2009), Alex Cox groups Cemetery Without Crosses with several other ‘art Westerns’: Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), Marlon Brando’s One-Eyed Jacks (1961) and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970). Like another French-Italian Continental Western, Sergio Corbucci’s Il grande silenzio (The Big Silence, 1968), Cemetery Without Crosses is a bleak picture about the cycle of violence, with a denouement that isn’t quite as downbeat as that of The Big Silence but which comes close to it. (A number of other Italian Westerns featured downbeat closing sequences: most prominent among them are Edoardo Mulargia’s La taglia è tua... l'uomo l'ammazzo io/El Puro, 1969; the original version of Franco Giraldi’s Un minuto per pregare, un instante per morire/A Minute to Pray… A Second to Die, 1968; and Angelo Pannacciò’s Lo ammazzò come un cane... ma lui rideva ancora/Death Played the Flute, 1972). Also like The Big Silence, Cemetery Without Crosses makes strong use of the environment: where The Big Silence was set in a snow-covered landscape that gave the film an eerie chill, Cemetery Without Crosses was filmed in the desert landscape of Almeria. The film’s environments are predominantly dirty and barren, the photography dominated by the drab colours of the desert and mud. As with The Big Silence, there’s a sense of verisimilitude to the costumes and sets: the buildings are worn and lived-in; the costumes are dusty and unclean. It’s an approach to narrative that would soon be replaced by the more outrageously upbeat and gimmicky Italian Westerns such as Gianfranco Parolini’s Sabata (1969) and its clones.  Also as with The Big Silence, the downbeat ending of Cemetery Without Crosses seems inevitable, signposted in Manuel’s early assertion about revenge ‘bearing bitter fruit’. It’s also foregrounded in the film’s title song, ‘A Rope and a Colt’, sung by Scott Walker of the Walker Brothers, foregrounds the picture’s status as a revenge Western from its opening verse (the lyrics are by Hollywood songwriter Hal Shaper): ‘I seek the man who killed my friend / And when we meet my life may end [….] I swore a vow on my dyin’ breath / To ride a trail that ends in death’. Also as with The Big Silence, the downbeat ending of Cemetery Without Crosses seems inevitable, signposted in Manuel’s early assertion about revenge ‘bearing bitter fruit’. It’s also foregrounded in the film’s title song, ‘A Rope and a Colt’, sung by Scott Walker of the Walker Brothers, foregrounds the picture’s status as a revenge Western from its opening verse (the lyrics are by Hollywood songwriter Hal Shaper): ‘I seek the man who killed my friend / And when we meet my life may end [….] I swore a vow on my dyin’ breath / To ride a trail that ends in death’.

The film is dedicated to Sergio Leone, and Leone supposedly directed the scene depicting Manuel dining with the Rogers after being hired by them. It’s a sequence that, like much of the rest of the film, is absent of dialogue: the warmth of the Rogers family is conveyed through their good-natured laughter and the practical joke they pull on Manuel with the jar of mustard and the jack-in-the-box. The carnivalesque qualities of this scene are in stark contrast with the austerity displayed in Maria’s dealings with Thomas and Eli. The dinner scene humanises the Rogers: we see them playing a practical joke, dining together warmly, laughing. They become more sympathetic as the film progresses, and the Caines less so – leading to their rape of Johanna and their betrayal of Maria and Manuel.  There is little dialogue, even in comparison with Leone’s films. David Milch, the creator of HBO’s series Deadwood (2004-6), has suggested that the source of the laconic cowboy in American Western films was the strictures put in place by the Motion Picture Production Code regarding obscenity (see ‘The New Language of the Old West’, a featurette on the HBO season 1 DVD release of Deadwood). Milch has said that faced with such prohibitions, filmmakers came to focus on the laconic hero: ‘So if characters can’t say anything obscene’, Milch has said, ‘you try and conceive a character for whom obscenity is a kind of fallen or pathetic expression of weakness. I believe that was the source of the development of the laconic cowboy. A man of few words, but deep and complicated morality, who didn’t have to fuck with the Hays Code’ (ibid). Rumour has it that Eastwood cut much of the dialogue written for his character, Joe, in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), translating the laconic protagonist of many American Westerns (especially revenge Westerns) to the western all’italiana. Subsequent Italian-style Westerns in the Leone style often featured men-of-few-words as their protagonists (for a considerable time, it seemed that Franco Nero’s stock-in-trade was playing such characters in films like Sergio Corbucci’s Django, 1966, and Il mercenario/A Professional Gun, 1968). The most extreme example of this is perhaps the aforementioned The Big Silence, in which the hero (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is actually mute, his utter silence caused by the slitting of his throat as a child by the sadistic bounty hunters who murdered his parents. Other Italian Westerns, of course, featured far more talkative protagonists, their excitability often either undermining their heroism or acting as a foil for it. One may recall the moment in Leone’s Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo/The Good, The Bad and the Ugly (1966) in which the frequently excitable Tuco (Eli Wallach) is confronted by a man he previously injured whilst he is comically bathing in a luxurious bubble bath in a deserted hotel (in the middle of a battle zone, no less). Tuco allows the man to wax lyrical about how he has spent years tracking down Tuco (‘I've been looking for you for 8 months. Whenever I should have had a gun in my right hand, I thought of you. Now I find you in exactly the position that suits me. I had lots of time to learn to shoot with my left’) before punctuating the man’s speech by shooting him with the gun he has concealed underneath the bubbles of his bath. ‘When you have to shoot, shoot; don’t talk’, Tuco advises the corpse. (It’s hard not to see this wise piece of advice as an allusion to Rico’s line in Mervyn LeRoy’s 1931 gangster picture Little Caesar, ‘Shoot first and argue afterwards’.) There is little dialogue, even in comparison with Leone’s films. David Milch, the creator of HBO’s series Deadwood (2004-6), has suggested that the source of the laconic cowboy in American Western films was the strictures put in place by the Motion Picture Production Code regarding obscenity (see ‘The New Language of the Old West’, a featurette on the HBO season 1 DVD release of Deadwood). Milch has said that faced with such prohibitions, filmmakers came to focus on the laconic hero: ‘So if characters can’t say anything obscene’, Milch has said, ‘you try and conceive a character for whom obscenity is a kind of fallen or pathetic expression of weakness. I believe that was the source of the development of the laconic cowboy. A man of few words, but deep and complicated morality, who didn’t have to fuck with the Hays Code’ (ibid). Rumour has it that Eastwood cut much of the dialogue written for his character, Joe, in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), translating the laconic protagonist of many American Westerns (especially revenge Westerns) to the western all’italiana. Subsequent Italian-style Westerns in the Leone style often featured men-of-few-words as their protagonists (for a considerable time, it seemed that Franco Nero’s stock-in-trade was playing such characters in films like Sergio Corbucci’s Django, 1966, and Il mercenario/A Professional Gun, 1968). The most extreme example of this is perhaps the aforementioned The Big Silence, in which the hero (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is actually mute, his utter silence caused by the slitting of his throat as a child by the sadistic bounty hunters who murdered his parents. Other Italian Westerns, of course, featured far more talkative protagonists, their excitability often either undermining their heroism or acting as a foil for it. One may recall the moment in Leone’s Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo/The Good, The Bad and the Ugly (1966) in which the frequently excitable Tuco (Eli Wallach) is confronted by a man he previously injured whilst he is comically bathing in a luxurious bubble bath in a deserted hotel (in the middle of a battle zone, no less). Tuco allows the man to wax lyrical about how he has spent years tracking down Tuco (‘I've been looking for you for 8 months. Whenever I should have had a gun in my right hand, I thought of you. Now I find you in exactly the position that suits me. I had lots of time to learn to shoot with my left’) before punctuating the man’s speech by shooting him with the gun he has concealed underneath the bubbles of his bath. ‘When you have to shoot, shoot; don’t talk’, Tuco advises the corpse. (It’s hard not to see this wise piece of advice as an allusion to Rico’s line in Mervyn LeRoy’s 1931 gangster picture Little Caesar, ‘Shoot first and argue afterwards’.)

Aside from the lack of dialogue spoken by the film’s protagonist, Cemetery Without Crosses takes some elements of its plotting from Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, including the iconography of the ghost town, the woman in mourning who dresses constantly in black (in Fistful, Marisol; in this film, Maria), the kidnap plot, and Joe/Manuel’s decision to pretend to work for the Rojos/Rogers in order to enact revenge in the name of Marisol/Maria. Also, as with Leone’s film, Cemetery Without Crosses is filled with Christian symbolism. The shot of the wounded Ben at the feet of Maria (whose name, of course, has Christian resonance) recalls the various paintings of the Pietà, such as Sebastiano del Piombo’s ‘Pietà’ (c.1517) or those of Francesco Trevisani. Rogers shoots Ben in his gun hand, which has obvious symbolism in relation to the Crucifixion. When Manuel enters the Rogers ranch for the first time, he sees Will Rogers having his feet washed by a servant, the composition recalling Renaissance paintings of Mary Magdalene washing the feet of Christ (for example, Nicolas Poussin’s ‘Anointing of Jesus at a Pharisee's home’). Finally, Thomas and Eli’s betrayal of Maria and Manuel is committed out of greed, in return for a sum of gold. Aside from the lack of dialogue spoken by the film’s protagonist, Cemetery Without Crosses takes some elements of its plotting from Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, including the iconography of the ghost town, the woman in mourning who dresses constantly in black (in Fistful, Marisol; in this film, Maria), the kidnap plot, and Joe/Manuel’s decision to pretend to work for the Rojos/Rogers in order to enact revenge in the name of Marisol/Maria. Also, as with Leone’s film, Cemetery Without Crosses is filled with Christian symbolism. The shot of the wounded Ben at the feet of Maria (whose name, of course, has Christian resonance) recalls the various paintings of the Pietà, such as Sebastiano del Piombo’s ‘Pietà’ (c.1517) or those of Francesco Trevisani. Rogers shoots Ben in his gun hand, which has obvious symbolism in relation to the Crucifixion. When Manuel enters the Rogers ranch for the first time, he sees Will Rogers having his feet washed by a servant, the composition recalling Renaissance paintings of Mary Magdalene washing the feet of Christ (for example, Nicolas Poussin’s ‘Anointing of Jesus at a Pharisee's home’). Finally, Thomas and Eli’s betrayal of Maria and Manuel is committed out of greed, in return for a sum of gold.

The film is one of a number of Westerns that Dario Argento is credited with writing or cowriting prior to his directorial debut, L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1969). Argento contributed to the scripts for Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West and Tonino Cervi’s Oggi a Me… Domani a Te (Today It’s Me, Tomorrow You, 1968). However, Argento’s input into the script for Cemetery Without Crosses is in dispute: Hossein has claimed that Argento’s name was only attached to the picture for the purposes of finance and distribution.    The film is uncut and runs for 90:46 mins.

Video

Cemetery Without Crosses is here presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The presentation is in the 1.66:1 screen ratio, and the compositions seem to work fine in this ratio.  The film was one of the many Italian Westerns to be released by Japanese DVD company SPO, as part of their ‘Macaroni Western Bible’, in the early 2000s. (SPO’s Cemetery Without Crosses DVD was released in 2004.) That period saw something of a boom of DVD releases of westerns all’italiana in Japan, and SPO’s disc of Cemetery Without Crosses was – considering the relative obscurity of the film at that point – something of an anomaly in the sense that the presentation was fairly handsome and anamorphically enhanced (in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio), where the vast majority of DVD releases of Italian Westerns contained non-anamorphic presentations. (The presentation was interlaced, however.) Since then, the film has been released on DVD in Germany, in a handsome limited edition wooden box, by Buio Omega through Anolis Films. The film was one of the many Italian Westerns to be released by Japanese DVD company SPO, as part of their ‘Macaroni Western Bible’, in the early 2000s. (SPO’s Cemetery Without Crosses DVD was released in 2004.) That period saw something of a boom of DVD releases of westerns all’italiana in Japan, and SPO’s disc of Cemetery Without Crosses was – considering the relative obscurity of the film at that point – something of an anomaly in the sense that the presentation was fairly handsome and anamorphically enhanced (in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio), where the vast majority of DVD releases of Italian Westerns contained non-anamorphic presentations. (The presentation was interlaced, however.) Since then, the film has been released on DVD in Germany, in a handsome limited edition wooden box, by Buio Omega through Anolis Films.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation is restored in 2k from an internegative that has seen some damage but is in mostly very good shape. The image is slightly softer than, say, Arrow’s recent Blu-ray release of Tonino Valerii’s roughly contemporaneous western all’italiana Day of Anger (1967), owing to the fact that this presentation is sourced from an internegative (two generations from the original negative) whereas the presentation of Day of Anger was sourced directly from the film’s negative: being two generations away from the original negative suggests that the internegative has slightly bolder contrast, a more pronounced grain structure and a slight loss in fine detail. That said, there’s remarkable detail on display in this presentation of Cemetery Without Crosses, with facial close-ups displaying a particularly strong level of fine detail considering the internegative source. The shorter focal lengths favoured in the production mean that many shots are staged in depth, and this deep focus staging is communicated nicely in this HD presentation. Some screengrabs comparing Arrow’s new Blu-ray release with the Japanese DVD release from SPO are included at the bottom of this review. (I don’t have access to the German DVD release from Buio Omega/Anolis, unfortunately.) As is evident from these grabs, Arrow’s release lacks the sepia tinting that, in the SPO presentation, is present in the film’s opening and closing sequences. (EDIT. Apparently, in the interview with Hossein that is included on the German DVD release from Anolis, he states that French release prints featured the monochrome opening and closing sequences, with the sepia tint being present only in Italian prints - so this release is commensurate with the presentation of the opening and closing sequences on French prints of the film.) However, Arrow’s release contains a substantial amount of extra information on all four sides of the frame. Although sourced from an internegative, the level of detail present in Arrow’s presentation is hugely impressive and a massive step up from SPO’s already-satisfying DVD release.  The internegative used for this presentation was apparently worn, and damage is more evident in some sequences than others. Brown spots appear here and there, indicating surface contamination and/or deterioration of the emulsion, and there are some colour shifts in some sequences (for example, in the colour of the sky during the sequence in which Johanna traverses the desert). Nevertheless, it’s wholly photochemical damage, natural given the age of the materials – and arguably far preferable to have a presentation with this natural, organic damage than one which has suffered from a heavy amount of digital tinkering to mitigate it. The internegative used for this presentation was apparently worn, and damage is more evident in some sequences than others. Brown spots appear here and there, indicating surface contamination and/or deterioration of the emulsion, and there are some colour shifts in some sequences (for example, in the colour of the sky during the sequence in which Johanna traverses the desert). Nevertheless, it’s wholly photochemical damage, natural given the age of the materials – and arguably far preferable to have a presentation with this natural, organic damage than one which has suffered from a heavy amount of digital tinkering to mitigate it.

The film’s palette has always been drab and muted, with the production design featuring dusty costumes favouring blacks and browns, and the Almeria locations communicating a barrenness that seems to blight the lives of the film’s protagonists. All of this is conveyed well in this Blu-ray release. Contrast is good too, with a strong tonal range present, and communicating the harshness of the light in the film’s desert setting very well. Finally, a characteristically strong encode resolves the detail within the image superbly, ensuring that the film has the natural, organic structure and texture of 35mm film.    NB. Larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with two audio options, both in LPCM 1.0 mono: English and Italian. Optional English HoH subtitles are available to accompany the English dub, and optional English subtitles translating the Italian dub are also present. Like most Italian Westerns, the audio in Cemetery Without Crosses was wholly post-synced, and both ‘dubs’ are therefore equally legitimate. Although the film features an international cast, Hossein and many of the film’s principal cast and crew were French, and so the absence of the French audio track is perhaps a little disappointing. Both tracks are equally robust and clean. The English track seems just a little cleaner and seems to have a little more range (evident particularly in Scott Walker’s opening theme song), but the difference between the two tracks is incredibly minor. It’s not a dialogue-heavy film by any means, with very little dialogue present throughout the picture. However, the English dub for this film is fine, better than those for many westerns all’italiana. Nevertheless, there are differences in the content of the dialogue, with the Italian track being a little more poetic. For example, when Maria approaches Manuel and asks him to help her against the Rogers, in the English track Manuel replies by telling her, ‘You believe in revenge, but I don’t’. By contrast, in the Italian dub Manuel makes the more poetic statement, ‘Revenge is a bad seed. It bears bitter fruit’. (This line resonates throughout the film, with Manuel and Maria bearing direct witness to the ‘bitter fruit’ wrought by Maria’s desire for revenge.)

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Remembering Sergio’ (5:18). This new interview with Hossein is conducted in French, with optional English subtitles. Hossein reflects on his work in Italy during the 1960s and the popularity of westerns all’italiana. He discusses the shooting of the film and his use of locations. Hossein also talks about his relationship with Leone and their shared dislike of flying, and reflects on Leone’s direction of the film’s dinner scene. - Location Report (7:57). Made for French television, this is presented in French with optional English subtitles. Filmed in monochrome at 1.33:1, the programme shows the shooting of the picture and features an interview with Hossein who discusses his aims with the film. Some of the film’s cast members are also interviewed about their roles in the film. - Archive Interview with Robert Hossein (2:27). Another piece originally shot for French television, this is again presented in French with optional English subtitles, and filmed in monochrome at 1.33:1. He is interviewed after the production of Cemetery Without Crosses and reacts slightly prickly to the suggestion that the film was made in the wake of the success of the Italian Westerns, saying that ‘it’s more to do with our childhood dreams […] of making Westerns’. - Trailer (3:51). This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

Packaging

Retail copies will include reversible sleeve artwork and one of Arrow’s characteristically lavish booklets, illustrated with stills from the film and featuring new articles about the film by Ginette Vincendeau and Rob Young.

Overall

Cemetery Without Crosses is an excellent, downbeat western all’italiana. Its minimalism and sombre tone makes it stand in stark contrast with some of the Italian Westerns which would follow it, and demonstrates Hossein’s confidence in allowing the photography, the mise-en-scène and the performances speak for themselves – without the need for pages of dialogue. The film’s handling of the theme of revenge is fascinating, and the passing of the baton of audience sympathy from the Caines to the Rogers takes place gradually. Ultimately, the warning that Manuel issued to Maria about the nature of revenge is confirmed by the film’s closing sequences. Cemetery Without Crosses is an excellent, downbeat western all’italiana. Its minimalism and sombre tone makes it stand in stark contrast with some of the Italian Westerns which would follow it, and demonstrates Hossein’s confidence in allowing the photography, the mise-en-scène and the performances speak for themselves – without the need for pages of dialogue. The film’s handling of the theme of revenge is fascinating, and the passing of the baton of audience sympathy from the Caines to the Rogers takes place gradually. Ultimately, the warning that Manuel issued to Maria about the nature of revenge is confirmed by the film’s closing sequences.

Arrow’s presentation of the film is very pleasing. Though sourced from an internegative which demonstrates some intermittent damage, it’s a very good presentation that is a huge step up from the film’s previous DVD releases. Certainly, it’s a very film-like presentation. The improvement in the level of detail visible on screen is almost astounding, and the characteristically excellent encode ensures that the presentation has the appearance of 35mm film – or as close as a digital simulacrum will allow. There’s some very good contextual material present too. Hopefully, Arrow’s excellent release of this deeply impressive Continental Western will allow the film to reach a wider audience. References: Cox, Alex, 2009: 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director’s Take on the Spaghetti Western. London: Kamera Books Comparison with the Japanese SPO DVD. Grabs from the SPO disc are on top; grabs from the new Arrow release are below. SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

SPO:

Arrow:

Example of surface contamination/deterioration of the emulsion:

Sample of large screengrabs:

|

|||||

|