|

|

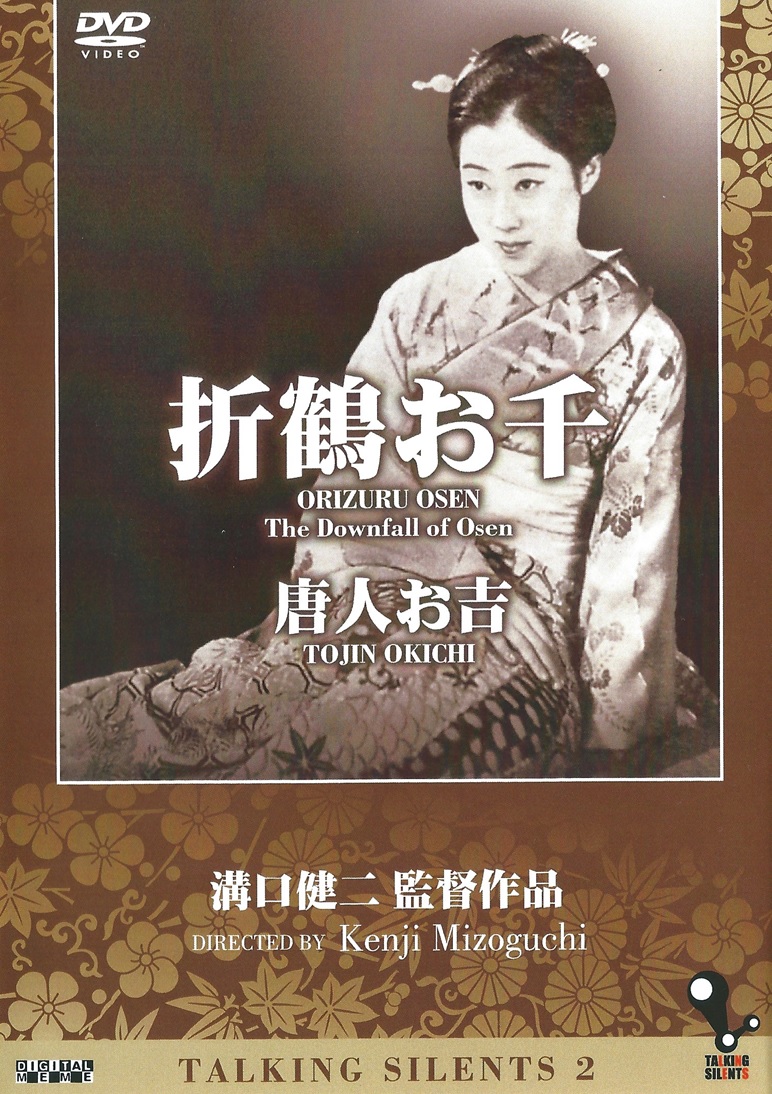

Downfall of Osen (The) AKA Orizuru Osen

R0 - Japan - Digital Meme Review written by and copyright: James-Masaki Ryan (7th September 2015). |

|

The Film

“Talking Silents 2” features two films directed by Kenji Mizoguchi: “The Downfall of Osen” (1935) and “Tojin Okichi” (1930) “The Downfall of Osen” (1935) On a stormy night in Tokyo at the busy Manseibashi station, countless commuters are stranded as a power failure due to the storm has caused trains to be delayed. On the overpacked platform is a gentleman in a suit by the name of Sokichi (played by Daijiro Natsukawa) who is looking over at the nearby Kanda Shrine, remembering when he went there when he was 17 years old. Also on the platform is a woman named Osen (played by Isuzu Yamada), who is also staring over at Kanda Shrine, as she also reminisces about an incident there that took place years ago. Although both were not aware of each other being on the station platform, they were both reminiscing of the same event: When they first met. Both Sokichi and Osen were living, or rather surviving in dire circumstances. Sokichi was from the countryside, dreaming of going to medical school and becoming a doctor, just like his late grandfather and late father were doctors. As he left his blind grandmother, he promised to return as a doctor but the reality of making it in Tokyo proved to be extremely harsh, as he had no friends or family there, no job, no money, and no place to lodge. As for Osen, she was a servant working at an antiques dealer’s place. But the antique dealer, Kumazawa (played by Arata Shibata) was not an honest one. Using his henchmen and Osen to try to swindle people into selling their antiques cheaply while Kumazawa sells for high prices, he was a man of power both financially and physically. As a servant, Osen worked under him as property with no means of escape, even though she had tried many times. Osen meets Sokichi at Kanda Temple, looking depressed and holding a knife in his hand. She offers him a place to stay through the kindness of her heart and asks him to come along with her. Though her intention was to help him, it continues to be hard conditions for both. Although Sokichi finds shelter at Kumazawa’s home, he is treated like dirt by Kumazawa and his men, as a servant without pay doing random things like cleaning and shopping. Osen promises to Sokichi that he mustn’t give up, and that she would help him somehow. As for Kumazawa, he is moving towards a big score: Golden Buddah statues at a nearby temple. Although the temple’s monk Fuboku (played by Ichiro Yoshizawa, later known as Mitsusaburo Ramon) is not interested in selling the statues, Kumazawa and his slick technique of smooth talking, feeding Fuboku some delicious food, getting Fuboku a bit tipsy with rice wine, and introducing the gorgeous Osen to him makes Fuboku alter his mind for reconsideration. Osen feels terribly guilty being used as bait, but with Kumazawa threatening her with a sword, there really was not choice. But how long will Sokichi and Osen continue to live in fear in such an abusive and threatening environment? Many of director Kenji Mizoguchi’s films have a unifying common theme, and that is the woman who sacrifices herself. Isuzu Yamada’s character of Osen is a character in which the audience is not given much on her character’s past. Shown are flashbacks of Sokichi’s grandmother and his reasons for coming to Tokyo, but as for Osen and what happened to her family is left unexplained. But maybe it is not necessary. What is important is that when she encounters Sokichi, for the first time she feels desire. Not a sexual desire, but one to take care of someone like a mother or an elder sister would. Seeing Sokichi in such a depressed state at the temple was almost like seeing a baby in a basket left in front of an orphanage. He was helpless, sad, and had nowhere to turn. Even though she was living in a condition that was not stable or manageable, it was still better than leaving him there all alone. Maternal instincts can often overpower practical reasoning. On the flipside is Sokichi who is in a simple sense, a loser. But coming from the countryside with only the dream of going to medical school, he certainly had ambition, but no practical reasoning. But like any naïve soul, he thought it would be normal for city folk to help him out, find a place to stay, and find a job. Instead he realizes the nature of the city and loses all hope quickly. For pretty much the first half of the film, he is in a quite useless state. He is picked on and abused by the henchmen, and he does not fight back or stand up for himself. But why are we following these two characters that seem to be without hope or common sense? Firstly at the start of the film the audience is shown that Sokichi has become a gentleman doctor, that both Osen and Sokichi have survived and somehow escaped from the clutches of Kumazawa, and that the two of them are not aware of each other on the train station platform. With these thoughts in the back of our minds, it gives a hopeful sense to the audience with a light at the end of the tunnel, rather than some of the other bleaker linear work in Mizoguchi’s filmography that plunges into tragedy, such as "The Water Magician" from 1933, or "The Life of Oharu" from 1952. The characters of Sokichi and Osen were hopeless by themselves, but it’s clear that they really needed each other to break free. She needed someone in her heart to take care of, and he needed someone that was willing to help him. As Sokichi states to her in the film, Osen is both a mother and a sister figure to him, and that is what keeps him going. The emotional connection is not a male-female love story as it is in the aforementioned "The Water Magician", nor is it of the sibling relationship in 1954’s “Sansho Dayu”. It is in actuality more similar to the relationship between director Mizoguchi and his older sister, who sacrificed herself to help the family, becoming a geisha after their father lost the family fortune. Kenji Mizoguchi had already been a film director for more than 10 years when he made “The Downfall of Osen” and his style was clearly established by this time. There are some quite amazing uses of camera movements in many scenes and also some experimental superimposition, like the montage of the hustle and bustle in Tokyo and for the scenes of madness with Osen’s confusion after being hospitalized. Although the camera movements are rather clunky considering that tracking was not exactly easy during the late silent age, he would later use tracking movements more frequently for long takes many of his later productions such as “The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums” (1939), “Ugestu Monogatari” (1953), and “Sansho Dayu” (1954). The pacing is rather smooth, but there are a lot of frustrating moments with Sokichi’s abuse - “Just get up and stand up for yourself! Do something for yourself!”, as you would like to scream. His character might be a bit too weak for anyone to cheer for, constantly crying for his blind grandmother and relying on Osen too much. Daijiro Natsukawa was 22 years old when he was supposed to be the 17 year old Sokichi. He initially entered Nikkatsu studios to become a director, but turned toward acting instead, debuting in 1934. Although he continued acting in films and later in television from the 1960’s, he never made it to the top billing of films. He died in 1987 at the age of 63. Isuzu Yamada was supposed to be playing a woman in her 20’s during the flashbacks in the film, so it should come as a surprise that she was only 18 years old when she starred as Osen. Debuting in film in 1930 at the age of only 13, Yamada starred in a series of films for Mizoguchi early in her career, including the talkies “Osaka Elegy” and “Sisters of the Gion” (which I still don’t know why the title isn’t “Sisters of Gion” instead, since Gion is a town’s name.) She consistently appeared in films through the years, including the unforgettable and powerful role as Lady Wakasa in “Throne of Blood” (1957) directed by Akira Kurosawa, “Flowing” (1956) for director Mikio Naruse, and “Tokyo Twilight” (1957) for director Yasujiro Ozu. From the 1960’s onward, Yamada continued regular appearances on television dramas, with her last role in 2000. In the same year, she received the “bunka kunsho” - The Order of Culture, an order that is presented by the Emperor to people who contribute to Japan's art, literature or culture. She was the first female actress to receive the order. She passed away in 2012 at the age of 95. Arata Shibata (who was also went by Shin Shibata) was born in 1903. His birth name was Yunoshin Kawakami, and starting his acting career on stage after university, and later debuted in film in 1933. He continued working at various studios, and later in his career in television. His last role was in an episode for a TV series in 1962, but nothing is known after that. If he were still alive today he would be well over 110 years old, but there seems to be no information anywhere on his whereabouts or his life after “retirement”. Ichiro Yoshizawa. was born Kenji Iwai in 1901. He went by the stage name Ichiro Yoshizawa debuting in 1927, but later in his career, he went by the better known alias Mitsusaburo Ramon, which “Ramon” was inspired from the 1925 “Ben Hur” actor Ramon Novarro. Mitsubaro Ramon had an impressive number of films to his credit before and after the war, appearing in almost 300 films altogether. Some of his leading credits were the “Peaceful Diary of the South” 3 film series (1931) and the “Journey to the West” 4 film series (1938-1939). Although he lost sight in his left eye in 1946, he continued acting, including appearing in the early Japanese special effects film “The Invisible Man Appears” in 1949, reuniting him with “The Downfall of Osen” co-star Daijiro Natsukawa. For Kenji Mizoguchi he also appeared in the films “The 47 Ronin” (1941),“Ugestu Monogatari” (1953), and “Tales of the Taira Clan” (1955). His final film role was in the 4th “Zatoichi” film, “Zatoichi the Fugitive” in 1963. He retired from acting the following year and lived in a nursing home. His life after that has been completely private, and it is not known when or where he died, or if he is still alive although unlikely. Interesting is the opening and closing sequences are at Manseibashi Station, which used to be one of the busiest train stations in Tokyo in the first half of the twentieth century, being the terminal station for the Chuo line. The red brick building was a standout of Meiji period western influenced architecture, along with its “twin” red brick Tokyo Station, but the building was destroyed during the 1923 earthquake. Although rebuilt afterwards, the station was closed in 1943 due to the nearby stations Kanda station and Akihabara station being more convenient transfer stations, and the main red brick building of the station was torn down. Although the building is gone, remnants of the station are visible, as the buildings under the elevated railway still use the red bricks from the original building and the middle platform still exists though trains do not stop there anymore. The Tokyo Railway Museum was located at the former station area from 1971 to 2006. It still attracts train enthusiasts as a “ghost station” in Tokyo, along with stations such as the abandoned “Ueno Museum-Zoo” station. “Tojin Okichi” (1930) “Tojin Okichi” was a novel by Gisaburo Juichiya written in 1928, published in 1929, and made into a feature film by director Kenji Mizoguchi at Nikkatsu in 1930. The Nikkatsu produced film was not the only one. In the same year in 1930 Kawai Productions also made an adaptation, and no less than 4 other adaptations followed in the 1930s. Taking place after United States Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s arrival to Japan in 1852 and the re-opening of Japan to the west, the story is of Okichi, a geisha who is made to entertain the foreign dignitaries. It is hard to assess the film since the 115 minute silent film does not survive in complete form, but only in a 4 minute fragment of a musical scene starring Yoko Umemura as the title character. Umemura first worked with Mizoguchi on the 1926 film “Paper Doll's Whisper of Spring” and continued collaborations in “Sisters of the Gion” (1936) and “The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums” (1939). During production on Mizoguchi’s 1944 film “Danjuro Sandai”, she fell ill and was hospitalized. Unexpectedly and suddenly, she died from peritonitis at the young age of 40 years old. Note: The DVD is region 0 NTSC, playable in any DVD player worldwide.

Video

Digital Meme presents both films in their original non-anamorphic 1.33:1 theatrical ratio in the NTSC standard. Both prints were sourced from theatrical film prints stored at the Matsuda Film Productions archive, the largest private film archive preserving silent films in Japan. Both films are preceded by the Matsuda Film Productions logo and text information about Matsuda and their commitment to preserving silent films for postwar audiences. “The Downfall of Osen” has quite good black and white levels, with dark blacks looking very good and whites not being blown out. The print is marred with scratches and tramline marks which is expected considering the age of the film. Digital restoration has been applied for more significant damage, but it is not overdone, keeping the look of film intact. Japanese intertitle cards are also easy to read, and the only significantly weak parts are the end reels with more damage and scratches than usual. “Tojin Okichi” is coming from a weaker source, possibly an 8mm print. The transfer is slightly windowboxed with black bars on all sides of the frame. The print is slightly askew so instead of a square shape so the bottom part of the frame is not entirely straight, but this seems to be inherent to the original film and not the transfer. The fragment has both opening and end credits for the digest film, like a music video, with Victor Records being credited.

Audio

There are 2 soundtrack options for “The Downfall of Osen”: Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono (Narration by Suisei Matsui) Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono (Narration by Midori Sawato) During the silent film era in the west it was common for theaters to have music accompaniment via organ or piano. In Japan it was common to have narrators next to the movie screen to do the voices, narrate the story, and read the intertitles out loud. These people were called “Benshi”. Music accompaniment was also used, making a unique way of viewing movies unusual to the west. People would not only flock to the theater to see their favorite movie stars on screen, but to hear their favorite benshi do the storytelling. The Suisei Matsui benshi narration track is a vintage recording, while the Midori Sawato recording is newly created for the DVD. The Matsui track has fidelity issues with hisses pops and cracks in the soundtrack making the narration hard to hear at times. The Sawato track on the other hand sounds very clear with both narration and music. Both films have Japanese intertitles with multiple subtitle tracks for the films: Optional English and Japanese subtitles for the narration by Suisei Matsui. Optional Chinese, English, Japanese, Korean subtitles for the narration by Midori Sawato. The white colored subtitles caption the narration and the intertitles. Although it is “authentic” to show the film with Japanese benshi narration to recreate the feel of a movie theater in the silent era, there isn’t an option for “silent” or “music only”. Technically, you could just turn off the sound and watch the film, but if subtitles are necessary, there isn’t a subtitle track to translate only the intertitles. There is one soundtrack available for “Tojin Okichi”: Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono The digest film is like a “music video” and it is synced to a vintage recording of the song for the film by Victor Records. There are no subtitles for the song, although the opening intertitles card has the song lyrics on screen in Japanese.

Extras

"Kenji Mizoguchi Revealed: Commentary by film historian Tadao Sato" featurette (19:03) Film critic Tadao Sato talks about the two films in this set, talking about the common theme of sacrificing women in Mizoguchi’s films, Mizoguchi’s father’s bankruptcy, and about Mizoguchi’s sister and their impact on his filmmaking. He also goes into the leftist movement in the 1930’s and also some interesting information about “Tojin Okichi” with historical context, and the initial very praised reception of the film which is sadly lost in its entirety. 1.33:1, in Japanese with optional Chinese, English, and Korean subtitles. "A Word From the Benshi - Midori Sawato" featurette (1:50) Narrator Midori Sawato gives a short introduction to Benshi narration and short comments about “The Downfall of Osen”. 1.33:1, in Japanese with optional English subtitles. The extras are informative, but less than 2 minutes for Sawato is way too short. I wish we could have gotten more information on her choices for vocal performances and additions she made to her version of the narration. Sato’s piece is at a good 19 minutes in runtime, but there are parts where he stumbles to find the correct words and when he looks at his notes. Maybe some audio editing and cutaways could have helped with the pacing, but overall, his comments are very informative.

Packaging

Packaged in a single-disc Amaray keep case, the packaging is bilingual in English and Japanese. Inside is a leaflet with cast & crew listings and biographies on Mizoguchi and the benshi narrators.

Overall

With “Talking Silents 1” and “Talking Silents 2”, we should be grateful that Digital Meme has released these rare Kenji Mizoguchi masterpieces of Japanese cinema on DVD. The DVD can be purchased on Amazon Japan or through Digital Meme’s website directly. This DVD is a 2007 release. Digital Meme has not had any new DVD releases recently, as the company has stated that the difficult DVD market has prevented them from releasing more sets in the home video marketplace. But they have also stated that they have new plans for 2016, which is very exciting news for silent Japanese film fans.

|

|||||

|