|

|

Zardoz (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th September 2015). |

|

The Film

Zardoz (John Boorman, 1974) Zardoz (John Boorman, 1974)

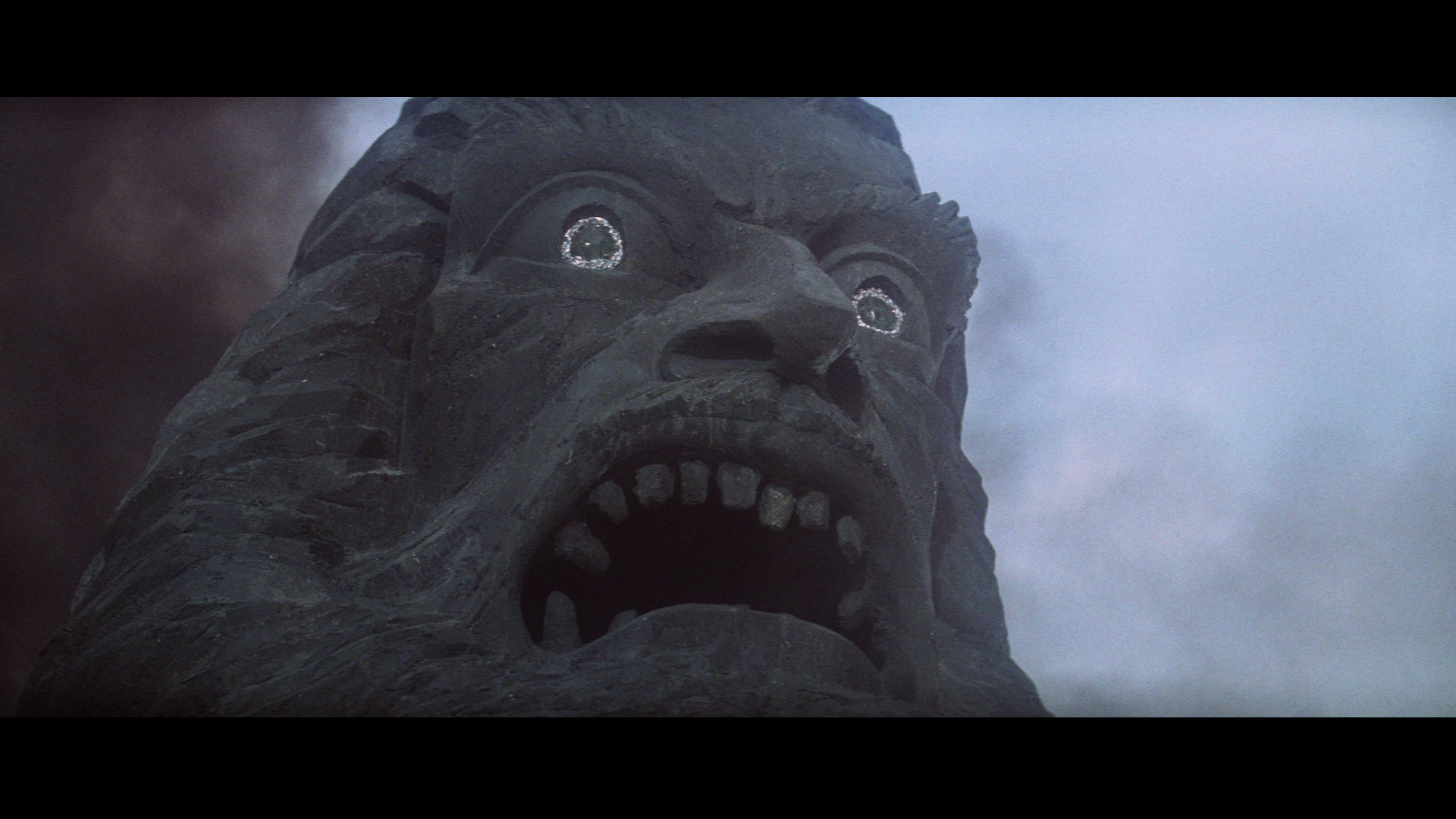

At one time, and arguably still, often slighted in discussion of the work of the director John Boorman – alongside Boorman’s 1977 sequel to William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), Exorcist 2: The Heretic – the 1974 film Zardoz is far more interesting than its reputation suggests. Mark Kermode has argued that during the 1970s Boorman became too invested in proving true the claims that he was an auteur ‘and promptly went off the rails’; Kermode reductively cites both Exorcist 2 and Zardoz to prove his point (Kermode, 2013: np). ‘Staggering as it may seem’, Kermode asserts, ‘the man who made Deliverance – one of the outstanding works of seventies cinema – followed it up with the worst science-fiction film ever made’ (ibid.). The rhetoric is recognisable and common within journalistic criticism: an antithetical statement which juxtaposes hyperbole with negative hyperbole; Deliverance with Zardoz. More temperedly, reviewing the film on its original release Roger Ebert referred to Zardoz simply as ‘an exercise in self-indulgence’ – with the underlying assumption that self-indulgence is a ‘bad thing’ – but qualified his assertion with the suggestion that the picture is ‘often an interesting one’ (Ebert, 1974: np). Ebert’s comment is arguably much more ‘on the money’: Zardoz is an odd, arguably confusing film that is the cinematic equivalent of Marmite, seemingly designed to divide audiences. ‘Self-indulgent’ seems to be the best way of describing it, though as suggested above self-indulgence in the world of cinema can be, and often is, utterly fascinating – if you’re on the filmmakers’ wavelength. As I Q Hunter has suggested, like A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971) and The Man Who Fell to Earth (Nicolas Roeg, 1976), Zardoz was ‘very different from the exploitation-horror that still accounted for most British sf’ but instead ‘reflected the new “art-movie” openness that entered all kinds of genre-film-making in the 1970s’ (Hunter, 1999: 11). In the special features on this Blu-ray release, Ben Wheatley discusses encountering Zardoz for the first time, with little warning and no prior knowledge of the film, via a late-night television screening and being bemused and fascinated by it. Of a similar age to Wheatley, my own first viewing was likewise via a late-night television broadcast, and provoked a similar reaction; though I was already cognisant of the film and was familiar with Boorman’s Deliverance, Hell in the Pacific, Excalibur and Point Blank – owing to a cinephile mother and grandfather, the former of whom had pre-warned me of the bizarre nature of Zardoz as the film in which Sean Connery spends all of his time in what is often referred to in discussions of the picture as a costume that resembles a giant red nappy. (Lately, though, in these post-Borat days that seems to have been amended to ‘mankini’.) It’s perhaps this image, so central to the iconography of the film, that alienates unexpecting first-time viewers; but certainly, in its handling of the image of Connery, Zardoz may be considered part of a series of films that Connery acted in during that era which deal with masculinity and masculine anxiety, including Sidney Lumet’s The Offence (1973) and John Huston’s The Man Who Would Be King (1975).  In 2293, the world is divided into the Outlands, populated by Brutals, and the Vortex, populated by Eternals who have discovered the secret to immortality. In the Outlands, a group of Brutals called Exterminators have been commanded by Zardoz – a giant, floating stone head who they worship as a deity – to participate in ‘hunts’ in which they quell the population of the Brutals. From the mouth of Zardoz spill guns which the Exterminators are intended to use on these hunts. In 2293, the world is divided into the Outlands, populated by Brutals, and the Vortex, populated by Eternals who have discovered the secret to immortality. In the Outlands, a group of Brutals called Exterminators have been commanded by Zardoz – a giant, floating stone head who they worship as a deity – to participate in ‘hunts’ in which they quell the population of the Brutals. From the mouth of Zardoz spill guns which the Exterminators are intended to use on these hunts.

One day, an apparently high-ranking Exterminator named Zed (Sean Connery) manages to sneak into the mouth of the giant stone head. There, he encounters – and kills – Arthur Frayn (Niall Buggy). Unbeknownst to Zed, Frayn is an Eternal who has been tasked by the other Eternals to manage the population of the Brutals. It is Frayn who has ‘piloted’ the stone head and issued the commands to the Exterminators. Carrying Zed, the stone head arrives in the Vortex, which is a curious mixture of the old (traditional stone farm buildings) and the new (finger rings which act as computers). Zed soon finds himself captured by the Eternals, including a scientist named May (Sara Kestelman) who expresses a profound interest in Zed’s unique attributes. He is also confronted by Consuella (Charlotte Rampling), who objectifies Zed and treats him as a subhuman before suggesting that he should be eliminated. Zed is soon given to Friend (John Alderton) to work as a slave. Friend, a friend of Frayn’s, queries the lack of a hierarchy within the society of the Eternals and also expresses a dissatisfaction with his immortality – evidencing a desire to die. Friend takes Zed to a building within the Vortex where ‘deviant’ Eternals who have questioned certain ideas within the society are given ‘sentences’ in which they are aged. There, Friend introduces Zed to one of the founders of the society within the Vortex. Soon, Friend finds himself placed among the ranks of deviant Eternals when he publicly questions the Eternal society’s blind emphasis on absolute equality.  Zed is left in the hands of May and Consuella, who continue to treat him as their pet science project. Zed tells them that one day, whilst on a hunt, he was led by a mysterious figure into the ruins of a library. There, Zed read voraciously, educating himself. He was also shown, by the individual whose true identity remains a mystery, a copy of L Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz – which Zed quickly deduced was the source of the name ‘Zardoz’, a realisation which led Zed to question Zardoz’s orders and caused Zed to sneak aboard the giant stone head. Making contact with Friend once again, Zed expresses a desire to help Friend destroy the Tabernacle, the source of the Vortex’s power, thus making the Eternals mortal. Zed is left in the hands of May and Consuella, who continue to treat him as their pet science project. Zed tells them that one day, whilst on a hunt, he was led by a mysterious figure into the ruins of a library. There, Zed read voraciously, educating himself. He was also shown, by the individual whose true identity remains a mystery, a copy of L Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz – which Zed quickly deduced was the source of the name ‘Zardoz’, a realisation which led Zed to question Zardoz’s orders and caused Zed to sneak aboard the giant stone head. Making contact with Friend once again, Zed expresses a desire to help Friend destroy the Tabernacle, the source of the Vortex’s power, thus making the Eternals mortal.

Seemingly influenced by the various New Wave cinemas within Europe during the 1950s and 1960s (especially Jean-Luc Godard’s alienated science fiction picture Alphaville, 1962), the films Boorman made following Point Blank in 1967 – including Hell in the Pacific (1968) and Deliverance (1972) – became increasingly abstract, their heavy stylisation often seeming to invite allegorical interpretations. Sue Harper and Justin Smith have suggested that many of Boorman’s films have settings which are historical (Excalibur, 1981), fantastical (Zardoz) or highly abstract (Hell in the Pacific), and that ‘Boorman preferred to make films which were not anchored in, but were critical of, contemporary life’ (Harper & Smith, 2012c: 143). Chris Petit has compared Point Blank with Godard’s Alphaville, arguing that both pictures use ‘the gangster/thriller framework to explore the increasing depersonalization of living in a mechanized urban world’ (Petit, quoted in Hoyle, 2012: 32). Sue Harper and Justin Smith contrast Boorman with Ken Russell. Where both filmmakers evidenced a fascination with the fantastic, Russell’s work was defined by excess whereas ‘Boorman made more pragmatic choices in order to free himself to dabble in the fantastic’ (Harper & Smith, 2012a: 132). Boorman’s ‘American projects’ – Point Blank, Hell in the Pacific and Deliverance – were ‘interspersed by two extraordinary British-made films: Leo the Last (1970) […] and Zardoz’ (ibid.). The ‘intensity’ of both of these pictures ‘show that they allude to something personal’, and both films possess a ‘jagged quality’ that is absent from the films Boorman made in America (ibid.) Zardoz, Harper and Smith say, ‘plays with ideas of culture and female power’ but ‘ultimately takes a conservative line on both’ (ibid.).  Harper and Smith group Zardoz with other science fiction films made in the 1970s which are ‘preoccupied with ideas about alternative ways of living which have their roots in 1960s counter-cultural aspirations’ (Harper & Smith, 2012c: 143). The Eternals’ aesthetic sensibility echoes the iconography of Ancient Egypt, with pyramids and Egyptian-style headdresses proliferating; they live in what is essentially a commune which is devoid of any hierarchy, something which Friend questions, leading to his punishment. (The Eternals also goad the Exterminators into rampaging through the Outlands, killing Brutals; in the Eternals commune-like lifestyle and hidden agenda of violence, the film perhaps intentionally echoes the dark undercurrent of the counterculture of the 1960s that is often seen as being embodied in Charles Manson and his ‘family’.) For Boorman, this ‘strange, voyeuristic story of a far future world where inhabitants of the bubble-covered Vortex cherish the secret of eternal life owes much […] to his six years in America [….] “It was about immortality being a fairy tale,” he [Boorman] said. “And America is the land where one sees this obsession with imagined permanence, this desire to perfect life and extend it forever”’ (Boorman, quoted in Callan, 2012: np). Harper and Smith group Zardoz with other science fiction films made in the 1970s which are ‘preoccupied with ideas about alternative ways of living which have their roots in 1960s counter-cultural aspirations’ (Harper & Smith, 2012c: 143). The Eternals’ aesthetic sensibility echoes the iconography of Ancient Egypt, with pyramids and Egyptian-style headdresses proliferating; they live in what is essentially a commune which is devoid of any hierarchy, something which Friend questions, leading to his punishment. (The Eternals also goad the Exterminators into rampaging through the Outlands, killing Brutals; in the Eternals commune-like lifestyle and hidden agenda of violence, the film perhaps intentionally echoes the dark undercurrent of the counterculture of the 1960s that is often seen as being embodied in Charles Manson and his ‘family’.) For Boorman, this ‘strange, voyeuristic story of a far future world where inhabitants of the bubble-covered Vortex cherish the secret of eternal life owes much […] to his six years in America [….] “It was about immortality being a fairy tale,” he [Boorman] said. “And America is the land where one sees this obsession with imagined permanence, this desire to perfect life and extend it forever”’ (Boorman, quoted in Callan, 2012: np).

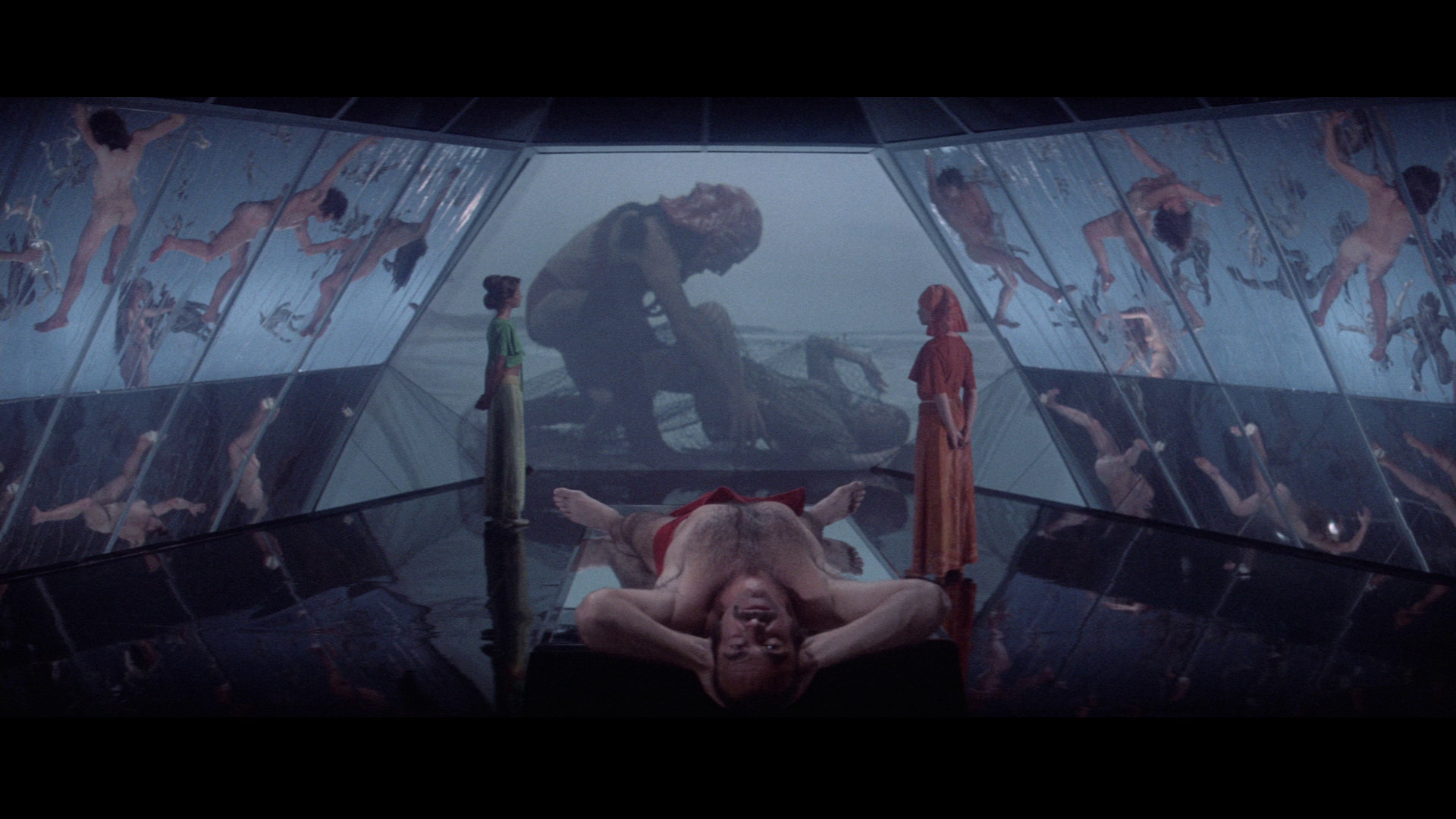

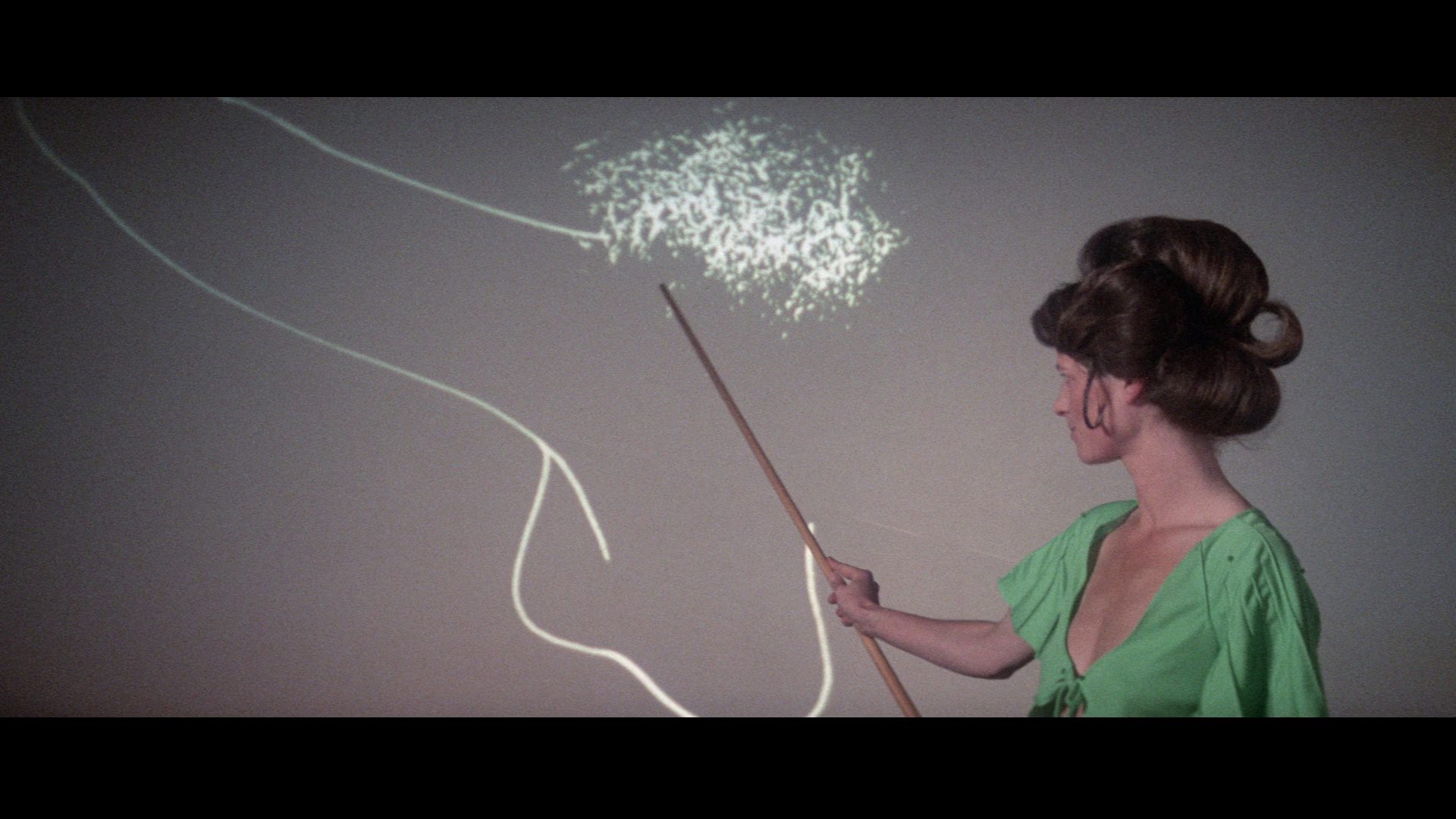

The Eternals’ society is a matriarchy, Harper and Smith remind us, and Zed brings with him both death – the sweet release from immortality that so many of the Eternals crave – and life, in the form of his ability to achieve an erection and procreate. The film’s ‘conservative line’ is highlighted in Zed’s ability at the climax of the film to turn Consuella away from her role as cold, frigid matriarch and transform her, via her desire for him, into the ‘proper role of mother and wife’ (Harper & Smith, 2012c: 143).  Early upon Zed’s arrival in the Vortex, Consuella arranges a demonstration of Zed’s ability to gain an erection. She plays for Zed, and her audience of Eternals, a scene recorded from Zed’s memory in which, during a hunt, he forced himself upon one of the female Brutals; her hope is that Zed will achieve an erection, something that is impossible for the male Eternals. However, this doesn’t happen. Instead, Zed achieves an erection whilst looking at Consuella. Humiliated, she looks at him with a mixture of confusion and anger. Zed, in close-up, looks down at his erection then back at Consuella with what Harper and Smith describe as ‘a rueful, half-apologetic expression’ (ibid.). As Harper and Smith suggest, ‘[i]t is this capacity for irony and self-mockery which marks him out as a superior being’ to the Eternals (ibid.). Early upon Zed’s arrival in the Vortex, Consuella arranges a demonstration of Zed’s ability to gain an erection. She plays for Zed, and her audience of Eternals, a scene recorded from Zed’s memory in which, during a hunt, he forced himself upon one of the female Brutals; her hope is that Zed will achieve an erection, something that is impossible for the male Eternals. However, this doesn’t happen. Instead, Zed achieves an erection whilst looking at Consuella. Humiliated, she looks at him with a mixture of confusion and anger. Zed, in close-up, looks down at his erection then back at Consuella with what Harper and Smith describe as ‘a rueful, half-apologetic expression’ (ibid.). As Harper and Smith suggest, ‘[i]t is this capacity for irony and self-mockery which marks him out as a superior being’ to the Eternals (ibid.).

In a 1974 interview, Boorman responded to what he referred to as ‘[t]he Women’s Lib people [who] think that the film is saying that male virilty is the only answer’ and ‘that what it comes down to in the end is that Zed has to bang some sense into these women’ by arguing that the opposite is true: ‘they bang some sense into him, don’t they?’ (Boorman, quoted in ibid.: 144). Later, in 1986 Boorman suggested that the Eternals' androgyny – their society in which ‘[b]oth men and women have become very delicate creatures, resembling each other and wearing the same clothes’ – was their ultimate downfall; he also cited an experiment which suggested that in an environment free of stress or the need to gather food, male mice retrenched into passive behaviour and allowed themselves to be dominated by the female of the species – which, Boorman argued, is an ethos represented in the matriarchal society of the Eternals (Boorman, quoted in ibid.). Ultimately, as Harper and Smith argue, Zardoz ‘is the film which, more intensely than any other in the decade, presents extreme sexual difference positively, but only as long as it is situated within the patriarchal order’ (ibid.).  After early test screenings of Zardoz, Boorman was pressured to add the film’s prologue, in which the disembodied head of Arthur Frayn floats against a black background and clarifies some of the narrative events that take place later in the film. The sequence adds a deliriously ‘meta’ aspect to Zardoz, framing the narrative that follows as a construct of Frayn – and reminding the viewer of the film that Frayn himself is a construct. Offering a clarification for some of the narrative events that follow this narration, Frayn declares: ‘I am Arthur Frayn, and I am Zardoz. I have lived three hundred years, and I long to die. But death is no longer possible. I am immortal’. Frayn foregrounds the film’s status as a story – and foregrounds the story’s status as a construct: ‘I present now my story full of mystery and intrigue; rich in irony, and most satirical. It is set deep in a possible future, so none of these events have yet occurred; but they may [….] In this tale, I am a fake god by occupation and a magician by inclination’. Frayn establishes himself as the author of this story and its guiding voice: ‘Man is my hero. I am the puppet master. I manipulate many of the characters and events you will see’. However, as Frayn reminds the audience, he himself is ‘invented too for your entertainment and amusement. And you, poor creatures’, he asks, ‘who conjured you out of the clay? Is God in showbusiness too?’ After early test screenings of Zardoz, Boorman was pressured to add the film’s prologue, in which the disembodied head of Arthur Frayn floats against a black background and clarifies some of the narrative events that take place later in the film. The sequence adds a deliriously ‘meta’ aspect to Zardoz, framing the narrative that follows as a construct of Frayn – and reminding the viewer of the film that Frayn himself is a construct. Offering a clarification for some of the narrative events that follow this narration, Frayn declares: ‘I am Arthur Frayn, and I am Zardoz. I have lived three hundred years, and I long to die. But death is no longer possible. I am immortal’. Frayn foregrounds the film’s status as a story – and foregrounds the story’s status as a construct: ‘I present now my story full of mystery and intrigue; rich in irony, and most satirical. It is set deep in a possible future, so none of these events have yet occurred; but they may [….] In this tale, I am a fake god by occupation and a magician by inclination’. Frayn establishes himself as the author of this story and its guiding voice: ‘Man is my hero. I am the puppet master. I manipulate many of the characters and events you will see’. However, as Frayn reminds the audience, he himself is ‘invented too for your entertainment and amusement. And you, poor creatures’, he asks, ‘who conjured you out of the clay? Is God in showbusiness too?’

Zardoz could be said to be a Rorschach test of sorts; it begs for interpretation, but its abstract qualities allow a viewer to interpret it in any number of ways. Boorman himself once suggested that the picture ‘doesn’t offer any rational meaning’ (Boorman, quoted in Hoyle, op cit.: 92). However, he also argued that the picture was, for him, in part an allegorical representation ‘of the way in which the “people of the developed world are extending [their] lifespan through advances in medicine, while the majority of the world is getting poorer and more abject”’ (Boorman, quoted in ibid.). The Eternals’ interference in the Outlands – their engineering of groups of Brutals into Exterminators who quell the population of the Outlands, and their use of the giant stone godhead from whose mouth spew guns for the Exterminators to use in their hunts – may be read, especially under Frayn’s assertion that the story of Zardoz is ‘rich in irony and most satirical’, as a comment on the then-current war in Vietnam that anticipates the Iran-Contra scandal of the 1980s and many later conflicts in which superpowers have ‘run interference’ in much poorer countries by arming groups of rebels. (‘Zardoz speaks to you, his chosen ones’, the booming voice of Zardoz tells the Exterminators, ‘You have been raised up from brutality to kill the Brutals who multiply and are legion. To this end, Zardoz, your god, gave you the gift of the gun [….] The penis shoots seeds and makes new life to poison the Earth with the plague of man […] But the gun shoots death and purifies the Earth of the filth of Brutals. Go forth and kill’.) While Zed, in the land of the Eternals, struggles to comprehend the concept of aesthetics in a traditional sense (he asks what the purpose of a flower is, and looks shocked when the computer tells him simply, ‘Decorative’), the more ‘civilised’ Eternals see beauty in the cruelty enacted by the Exterminators: during a replaying of Zed’s memories of a hunt, one of the Eternals asserts ‘He [Arthur, who engineered the violence of the Exterminators] is an artist. He does it with imagination’. Meanwhile, another female Eternal declares the footage to be ‘terribly exciting’. ‘What of the suffering?’, her male companion queries. ‘Oh, you can’t equate their [the Brutals’] feelings with ours. They’re just entertainment’.  The same scene also appears to offer a subtle dig at Hollywood cinema: watching Zed’s memories of the slaughter of Brutals on a large screen, an observer comments, ‘The memories are simple heroics. There are no abstractions, you notice’. Within this context, Frayn’s assertion of his ‘authorship’ of the story that follows, and then his murder by Zed which is followed by a long period of absence before the ‘reconstructed’ Frayn reappears at the climax of the film, seems designed to be read as a poststructuralist piece of meta-fiction, a comment on Barthes’ ‘Death of the Author’: Frayn establishes his ownership of the tale before being ‘killed’ by his own creation (Zed), following which the story and its hero (Zed) seem to lose any obvious sense of direction – his will being subjected to the whims of other Eternals – before Frayn reappears at the climax and suggests that the purpose Zed has seemingly found for himself (re-establishing death within the Vortex and destroying the controlling Tabernacle) was over a long period of time carefully engineered by Frayn and Friend. Of course, this is dependent on the viewer’s familiarity with Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, to which Zardoz alludes overtly – with Frayn, an amateur conjuror who establishes himself as a god, standing in for Oscar Zoroaster Diggs, the circus magician from Omaha who masquerades as ‘the great and powerful’ Wizard of Oz. Where ‘Oz’ is a contraction of Oscar Zoroaster Diggs, ‘Zardoz’ is a contraction of the Wizard of Oz. Zed refers to the moment in which the mysterious figure (actually Frayn) led him to a library and, specifically, a copy of Baum’s novel as a ‘loss of innocence’, declaring that ‘The Wizard of Oz was a fairy story about an old man who frightened people with a loud voice and a big mask [….] You must remember the end of the story: they looked behind the mask and found the truth. I looked behind the mask and I saw the truth. Zardoz’. The same scene also appears to offer a subtle dig at Hollywood cinema: watching Zed’s memories of the slaughter of Brutals on a large screen, an observer comments, ‘The memories are simple heroics. There are no abstractions, you notice’. Within this context, Frayn’s assertion of his ‘authorship’ of the story that follows, and then his murder by Zed which is followed by a long period of absence before the ‘reconstructed’ Frayn reappears at the climax of the film, seems designed to be read as a poststructuralist piece of meta-fiction, a comment on Barthes’ ‘Death of the Author’: Frayn establishes his ownership of the tale before being ‘killed’ by his own creation (Zed), following which the story and its hero (Zed) seem to lose any obvious sense of direction – his will being subjected to the whims of other Eternals – before Frayn reappears at the climax and suggests that the purpose Zed has seemingly found for himself (re-establishing death within the Vortex and destroying the controlling Tabernacle) was over a long period of time carefully engineered by Frayn and Friend. Of course, this is dependent on the viewer’s familiarity with Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, to which Zardoz alludes overtly – with Frayn, an amateur conjuror who establishes himself as a god, standing in for Oscar Zoroaster Diggs, the circus magician from Omaha who masquerades as ‘the great and powerful’ Wizard of Oz. Where ‘Oz’ is a contraction of Oscar Zoroaster Diggs, ‘Zardoz’ is a contraction of the Wizard of Oz. Zed refers to the moment in which the mysterious figure (actually Frayn) led him to a library and, specifically, a copy of Baum’s novel as a ‘loss of innocence’, declaring that ‘The Wizard of Oz was a fairy story about an old man who frightened people with a loud voice and a big mask [….] You must remember the end of the story: they looked behind the mask and found the truth. I looked behind the mask and I saw the truth. Zardoz’.

Zardoz, as presented here, is uncut and runs for 106:04 mins.

Video

Sue Harper and Justin Smith cite Boorman as one of the ‘innovative directors’ of the 1970s who ‘took control of the camera and dominated the “look” of their films’ (Harper & Smith, 2012b: 155). Boorman, in their words, ‘intervened powerfully in the cinematography and lighting of Zardoz, insisting on a diffused pastel effect to offset the violence concealed within the narrative’ (ibid.). He also helped to design the costumes alongside his wife, Christel Kruse Boorman. Christine Cornea compares Zardoz with Ken Russell’s Altered States in terms of its ‘veritable bricolage of artistic imagery, in which old and new are placed together, side by side’ (Cornea, 2007: 101). Sue Harper and Justin Smith cite Boorman as one of the ‘innovative directors’ of the 1970s who ‘took control of the camera and dominated the “look” of their films’ (Harper & Smith, 2012b: 155). Boorman, in their words, ‘intervened powerfully in the cinematography and lighting of Zardoz, insisting on a diffused pastel effect to offset the violence concealed within the narrative’ (ibid.). He also helped to design the costumes alongside his wife, Christel Kruse Boorman. Christine Cornea compares Zardoz with Ken Russell’s Altered States in terms of its ‘veritable bricolage of artistic imagery, in which old and new are placed together, side by side’ (Cornea, 2007: 101).

This Blu-ray presentation of Zardoz handles these qualities of the film’s aesthetic very nicely. Taking up approximately 31Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc (and using the AVC codec), the 1080p presentation of the film is in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The disc evidences excellent contrast levels, handling the transition from the mostly harsh light of the sequences in the Outlands to the diffuse light of the scenes set inside the Eternals’ various buildings very well. Boorman reputedly hired Geoffrey Unsworth to shoot the film because he (Boorman) was impressed with Unsworth’s combination of ‘soft lighting, diffusion filters, and smoke on the set’ that ‘made his [Unsworth’s] color photography “resemble an impressionistic painting”’ – qualities which, Boorman felt, made Unsworth the ideal cinematographer for Zardoz (Hoyle, op cit.: 100; the quote within the quote is from John Boorman). In collaboration, Unsworth and Boorman attempted to replicate the transition from monochrome to colour that takes place in the 1939 film version of The Wizard of Oz (perhaps the best known version of the story) by shooting the sequences set in the Outlands and those within the Vortex differently: the Outlands ‘are drained of all color save the blood-red leather clothes worn by the Exterminators’, whereas the scenes set in the Vortex have a ‘lush palette, which owes a great deal to the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’ (ibid.). (As Hoyle notes, the death of one of the Eternals refers directly to the imagery within Millais’ The Death of Ophelia.) Many sequences are shot with a strong depth of field, and this is communicated well in this presentation – which has a pleasing sense of depth to the image, and the level of fine detail present in, for example, close-ups is very pleasing indeed. Finally, a characteristically strong encode ensures that the presentation has the organic structure of 35mm film. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

There are two audio options: (1) a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, and (2) a DTS-HD Master Audio 3.0 surround track. The latter is more ‘true’ to the film’s original mix. Both tracks are clean and clear throughout. Ambient sounds (for example, the sound of the wind in the opening sequences) seem to be much lower in volume in the DTS-HD MA 3.0 surround track. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes an impressive array of contextual material:  - an audio commentary with John Boorman. Recorded in 2001, this is the same commentary that appeared on the film’s previous DVD releases. Boorman waxes philosophical about the film and offers some strong discussion of its themes. Boorman talks about shooting the film near his home in the Wicklow Hills, Ireland, and also reflects on his original intention to cast Burt Reynolds in the picture. There’s some good discussion of how some of the effects (such as the floating stone head) were achieved. Boorman also talks about the genesis of the idea for the film, which he suggests originated in a reading of Aldous Huxley’s story ‘After Many a Summer’ when Boorman was young. There are some wonderful anecdotes about Connery apparently threatening one of the film’s technicians over the accidental junking of the makeup intensive time-lapse footage at the end of the picture, and Connery suggesting to Boorman that they sack Connery’s driver and split the man’s wages between them. - an audio commentary with John Boorman. Recorded in 2001, this is the same commentary that appeared on the film’s previous DVD releases. Boorman waxes philosophical about the film and offers some strong discussion of its themes. Boorman talks about shooting the film near his home in the Wicklow Hills, Ireland, and also reflects on his original intention to cast Burt Reynolds in the picture. There’s some good discussion of how some of the effects (such as the floating stone head) were achieved. Boorman also talks about the genesis of the idea for the film, which he suggests originated in a reading of Aldous Huxley’s story ‘After Many a Summer’ when Boorman was young. There are some wonderful anecdotes about Connery apparently threatening one of the film’s technicians over the accidental junking of the makeup intensive time-lapse footage at the end of the picture, and Connery suggesting to Boorman that they sack Connery’s driver and split the man’s wages between them.

The disc also includes a number of new interviews: - John Boorman (21:59). Boorman discusses the origins of the film in his observation that ‘the rich get richer and the poor get poorer’. He talks about the relationships between the ‘three types’ within the film: the Eternals, the Apathetics, and the Brutals. Boorman reflects on Point Blank, his first colour film, which was designed to be ‘monochromatic’, and his working relationship with William Stair. The film was intended ‘to be mysterious’, and during editing Boorman began to feel that the film was a little ‘too obscure’ and tried to add a greater sense of clarity to it. Boorman also reflects on the reception of the film, particularly in France where a communist newspaper suggested that the stone head was based on Karl Marx (an interpretation that persists to this day) and that Boorman was ridiculing Marx; Boorman, however, insists that the stone head was in fact modeled on his own face. - actor Sara Kestelman (16:54). Kestelman discusses how she came to be cast in the film. She talks about her preparation for her role in the picture. The design of the costumes used within Zardoz, along with the hair and makeup, is examined. - production designer Anthony Pratt (17:32). Pratt discusses his work with Boorman and suggests that Boorman considered Lee Marvin for the role of Zed prior to Burt Reynolds. Pratt suggests that the film ‘probably goes down as one of the strangest commercial films ever made’. The design of the stone head is examined, alongside the film’s contrast between the worlds of the Outlands and the Vortex. - special effects artist Gerry Johnston (21:18). Johnston reflects on his career more generally before talking about Zardoz and the achievement of the effect of the flying stone head. He also talks about some of the smaller effects in the film: the use of squibs, the tanks in which the ‘reconstructed’ Eternals are held, the smashing of the statues towards the end of the film. - camera operator Peter MacDonald (15:28). MacDonald talks about his work with Geoffrey Unsworth on the film and his excitement at the prospect of working on a film with Boorman. MacDonald suggests that ‘in some ways, the film is more relevant now than it was then’. He reflects on the film’s photography, especially the logistics involved in shooting the ‘hall of mirrors’ sequence. The photography ‘has that rough edge to it’ that Boorman desired. - assistant director Simon Relph (13:46). Relph talks about how he came to be involved in the production of Zardoz and some of the difficulties in shooting the picture – including the sequences in which projectors are used and the logistics of shooting a sequence with a black sky (achieved, Relph reveals, by burning car tyres). Relph talks about Lee Marvin’s visit to the set. He discusses the reception of the picture, ‘quite a way out film’, and the ‘growing community of people who enjoy it’. - hair stylist Colin Jamison (8:47). Jamison reflects on the hair styles within the film and Connery’s wig, and offers some amusing anecdotes about the production. - production manager Seamus Byrne (9:31). Byrne reflects on the locations used during the shooting of the film, the guns used in the film – particularly the revolver used by Connery in the picture – and suggests that Zardoz ‘bookended the Sixties’ for him, marking the point at which ‘we were definitely in the Seventies’. - assistant editor Alan Jones (7:38). Jones discusses the sequences in which footage is projected onto the actors, particularly Connery. He reflects on working with Connery and talks about the infamous incident in which the final sequence, depicting the ageing of Zed and Consuella via a series of makeup changes, was accidentally junked (when the clapper loader accidentally opened the tin containing the film prior to it being developed). - Ben Wheatley (16:24), who has nothing to do with the film other than being an enormous fan of it. It’s always nice to see Wheatley interviewed in such a context as he’s such an enthusiastic cinephile. Here, Wheatley talks about his first exposure to the film, and the differences between being a young film fan in the days before the Internet – where it was possible to stumble across a film on television and know next to nothing about it – and the virtual impossibility of having such a ‘cold’ viewing today. He also reflects on what Zardoz means for him. - Trailer (3:09). - Radio Spots (2:58). Retail versions of the release will included Arrow’s usual reversible artwork and a lavishly-illustrated booklet which includes archive interviews along with new writing about the film by Julian Upton and Adrian Smith. There was an episode of BBC’s Omnibus programme which focused on Zardoz and featured comments from Boorman during its production and post-production; it’s a shame this couldn’t be included – or the Boorman-penned novelisation of the picture, which has long been out of print.

Overall

Zardoz is a flawed film – but a fascinating one, especially if you’re on its wavelength. (Boorman himself concedes to this in his commentary, suggesting that some aspects of the picture are ‘laughable’ if you’re not in tune with it.) Certainly, some of the ideas within the film still seem fresh and relevant, even though the execution may be, in Roger Ebert’s words, ‘self-indulgent’ – but then, some of the most important films in cinema history could be labeled as equally ‘self-indulgent’, so where’s the harm in that? Zardoz is a flawed film – but a fascinating one, especially if you’re on its wavelength. (Boorman himself concedes to this in his commentary, suggesting that some aspects of the picture are ‘laughable’ if you’re not in tune with it.) Certainly, some of the ideas within the film still seem fresh and relevant, even though the execution may be, in Roger Ebert’s words, ‘self-indulgent’ – but then, some of the most important films in cinema history could be labeled as equally ‘self-indulgent’, so where’s the harm in that?

Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains a superb presentation of the film and a very pleasing array of contextual material, including some enlightening new interviews. Once again, Arrow provide a pretty much essential release of a cult favourite. References: Callan, Michael Feeney, 2012: Sean Connery. London: Random House Cornea, Christine, 2007: Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality. Edinburgh University Press Ebert, Roger, 1974: ‘Zardoz’ (review). [Online.] http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/zardoz-1974 Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin, 2012a: ‘Key Players’. In: Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin (eds), 2012: British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh University Press: 138-54 Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin, 2012b: ‘Technology and Visual Style’. In: Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin (eds), 2012: British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh University Press: 155-72 Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin, 2012c: ‘Boundaries and Taboos’. In: Harper, Sue & Smith, Justin (eds), 2012: British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh University Press: 138-54 Hoyle, Brian, 2012: The Cinema of John Boorman. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Hunter, I Q, 1999: ‘Introduction: the strange world of the British science fiction film’. In: Hunter, I Q (ed), 1999: British Science Fiction Cinema. London: I B Tauris: 1-15 Kermode, Mark, 2013: Hatchet Job: Love Movies, Hate Critics. London: Pan Macmillan

|

|||||

|