|

|

Firemen's Ball (The) AKA Fireman's Ball AKA Horí, má panenko (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th October 2015). |

|

The Film

The Firemen’s Ball (Milos Forman, 1967) The Firemen’s Ball (Milos Forman, 1967)

One of the most important filmmakers associated with the Czech New Wave, Milos Forman focused his work predominantly on the lives of the working classes whilst also lampooning authority. There are some strong parallels between Forman’s anti-authoritarian films and the work of a key anti-establishment filmmaker associated with the British New Wave, Lindsay Anderson – who, like Forman, also collaborated with the Czech cinematographer Miroslav Ondricek. (Ondricek lensed films for Forman, including The Firemen’s Ball, in both Czechoslovakia and America; and Ondricek also photographed If…., 1968, and O Lucky Man, 1973, for Anderson.) Aaron Sultanik has suggested that Forman’s early Czech films, including The Firemen’s Ball, are characterised by ‘a genuine folk sensibility’ that evidences itself in their aesthetic: they ‘look as though they were made by one of his [Forman’s] rustic characters’ (Sultanik, 1986: 185). The film focuses on a group of amateur firemen who focus their annual ball on celebrating the work of their 86 year old former president, who unbeknownst to him has been diagnosed with cancer. The firemen intend to present this highly respected member of their group with the gift of a golden fireaxe. Other than the presentation of the golden fireaxe, the centerpiece of the ball is the grand prize raffle. However, the firemen gradually become aware that someone – or perhaps a group of people – is/are stealing the raffle prizes from the table. Inspired by a photograph of the Miss World contest, the firemen also decide to hold a beauty contest. At first, they resist attempts at bribery (which has the aim of encouraging the firemen to consider a specific young woman as part of the contest). However, when their original list of competitors is lost in a scuffle, the firemen allow their judgement to be influenced by persuasive rhetoric and the promise of bribery.  Things come to a head when the alarm sounds and the firemen are called to a blaze at an elderly man’s house. The firemen struggle to extinguish the blaze, and are ultimately unsuccessful: the house burns to the ground, leaving its occupant homeless. Returning to the ball, the firemen arrange a collection of raffle tickets for the elderly man – and they present these raffle tickets to the man publicly. The elderly man refuses the raffle tickets, stating that they are no help in a situation in which he has lost everything – his home and all of his worldly possessions. Furthermore, as the firemen soon discover, all of the raffle prizes have been stolen: the table has been stripped bare. Things come to a head when the alarm sounds and the firemen are called to a blaze at an elderly man’s house. The firemen struggle to extinguish the blaze, and are ultimately unsuccessful: the house burns to the ground, leaving its occupant homeless. Returning to the ball, the firemen arrange a collection of raffle tickets for the elderly man – and they present these raffle tickets to the man publicly. The elderly man refuses the raffle tickets, stating that they are no help in a situation in which he has lost everything – his home and all of his worldly possessions. Furthermore, as the firemen soon discover, all of the raffle prizes have been stolen: the table has been stripped bare.

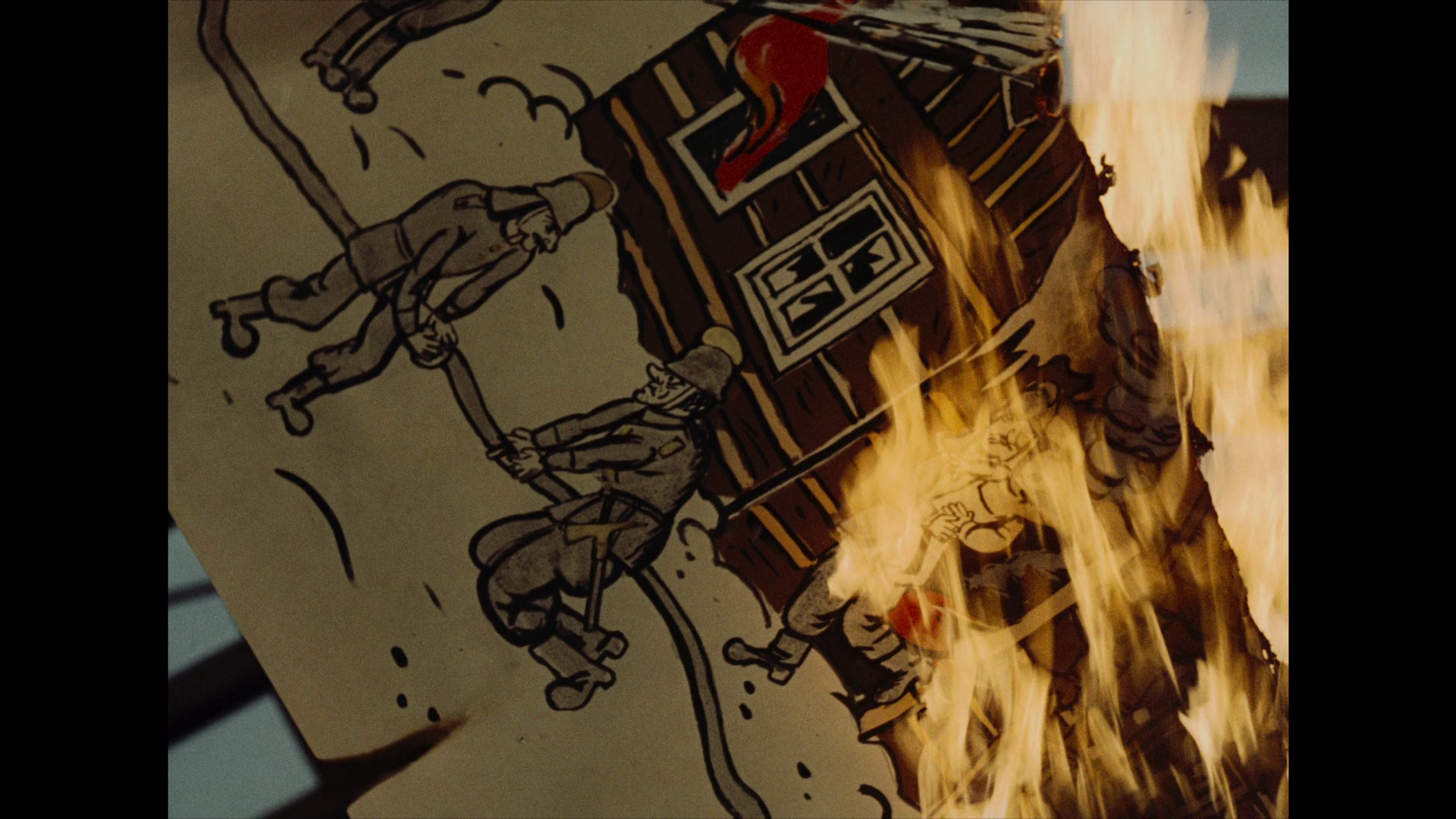

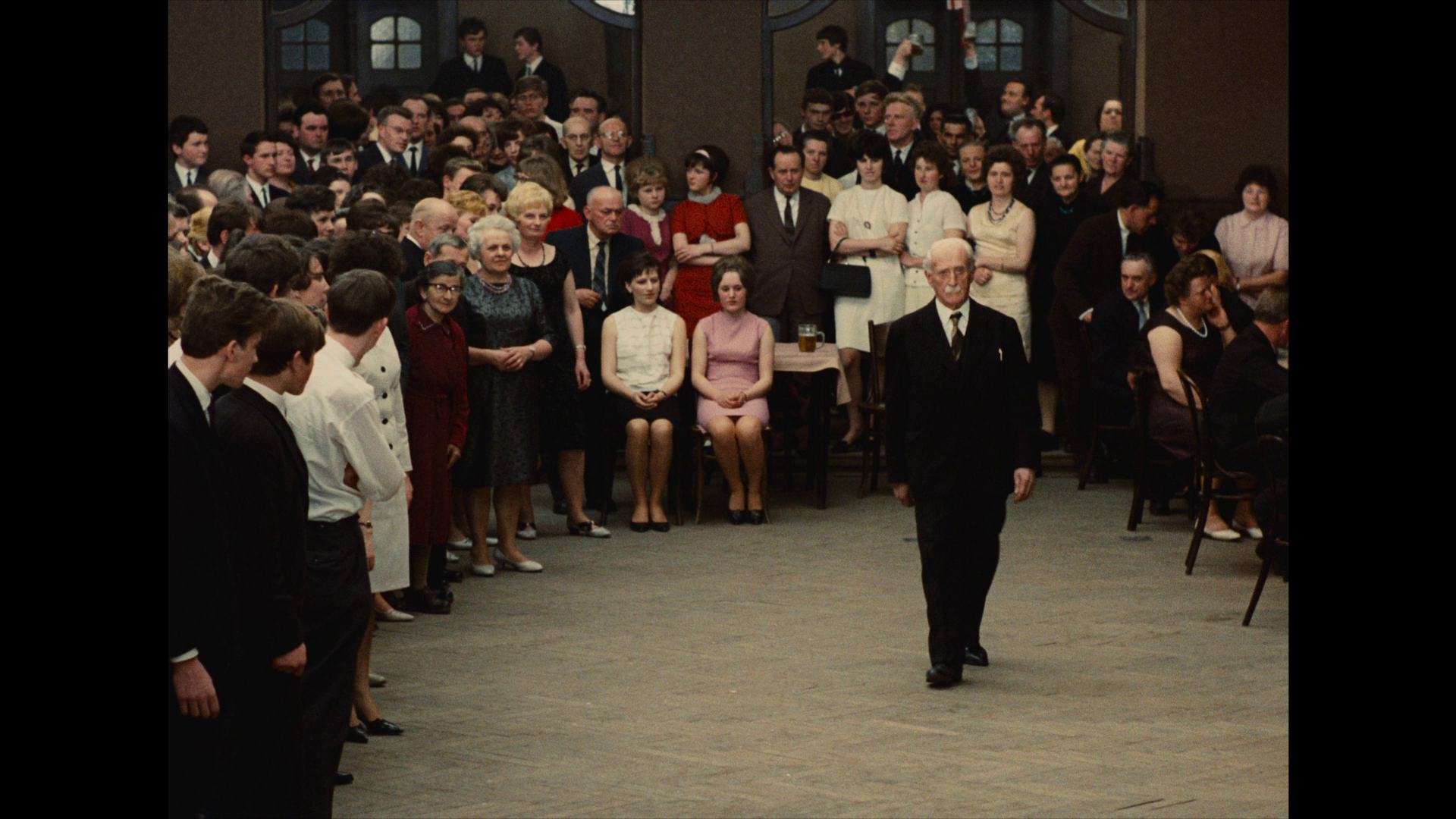

As David Sorfa argues in his interview on this Blu-ray release of The Firemen’s Ball (1967), Forman’s work – both his Czech films (Audition, and the pictures he made in America (for example, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975; and The Man in the Moon, 1999) – focuses largely on the theme of performance or performativity. In The Firemen’s Ball, as Sorfa suggests, this theme is enacted through the focus on the amateur firemen who stage the ball, who ‘perform’ as firemen and, within the ball itself, also ‘perform’ as judges in an impromptu beauty contest. Ullrich Kockel has argued that Forman’s application of the concept of performativity and the idea of ‘disguise, grotesquerie, and the subversion of the natural order’ connects The Firemen’s Ball with Bakhtin’s notion of the carnivalesque (Kockel, 2015: 209). In the context of the film, this satirical method is directed towards puncturing ‘the firemen’s tendency toward self-important official rhetoric and coercive authoritarianism’ (Hoberman, quoted in ibid.).  From the outset, the firemen’s judgement is questioned by Forman’s camera. The film begins with close-up shots of the treasured golden fireaxe being passed amongst the firemen, who are seated at a table. They question the very premise on which the celebrations are to be based, asking if it is inappropriate to present the axe to their 86 year old colleague owing to his recent diagnosis with cancer. ‘It’s as if we’re rushing to give it [the axe] before it’s too late’, one of the firemen suggests. Following this, we see the preparations immediately before the ball. A beautiful hand-drawn banner is being hung from the ceiling of the hall by a younger man who is standing on a ladder; the young man’s attention is turned to singing the edges of the banner symbolically, with a blow torch. The ladder on which he stands is footed by one of the firemen, Vazlav. Vazlav and another of the firemen, Josef, argue over the disappearance of one of the raffle prizes (a chocolate cake) – the first of many thefts from the raffle prize table. Vazlav insists that, footing the ladder, he is unable to see the raffle prize table; Josef argues that Vazlav was capable of witnessing the theft. Caught up in the argument, Vazlav moves away from the ladder which, to no-one’s surprise other than Josef’s, falls to the floor causing the younger man to become injured, and the blow torch ignites the banner causing it to be destroyed by fire whilst, below, Josef and Vazlav struggle to operate a simple fire extinguisher. With this, the masquerade enacted by these amateur firemen is established for the audience – and consolidated towards the end of the film when they struggle to contain the blaze at the home of the elderly man. The ball itself descends into chaos when the revelation that prizes have been stolen from the raffle is made, with the firemen becoming intent on discovering who is responsible for stealing the prizes – turning the ball into something which resembles a witchhunt. From the outset, the firemen’s judgement is questioned by Forman’s camera. The film begins with close-up shots of the treasured golden fireaxe being passed amongst the firemen, who are seated at a table. They question the very premise on which the celebrations are to be based, asking if it is inappropriate to present the axe to their 86 year old colleague owing to his recent diagnosis with cancer. ‘It’s as if we’re rushing to give it [the axe] before it’s too late’, one of the firemen suggests. Following this, we see the preparations immediately before the ball. A beautiful hand-drawn banner is being hung from the ceiling of the hall by a younger man who is standing on a ladder; the young man’s attention is turned to singing the edges of the banner symbolically, with a blow torch. The ladder on which he stands is footed by one of the firemen, Vazlav. Vazlav and another of the firemen, Josef, argue over the disappearance of one of the raffle prizes (a chocolate cake) – the first of many thefts from the raffle prize table. Vazlav insists that, footing the ladder, he is unable to see the raffle prize table; Josef argues that Vazlav was capable of witnessing the theft. Caught up in the argument, Vazlav moves away from the ladder which, to no-one’s surprise other than Josef’s, falls to the floor causing the younger man to become injured, and the blow torch ignites the banner causing it to be destroyed by fire whilst, below, Josef and Vazlav struggle to operate a simple fire extinguisher. With this, the masquerade enacted by these amateur firemen is established for the audience – and consolidated towards the end of the film when they struggle to contain the blaze at the home of the elderly man. The ball itself descends into chaos when the revelation that prizes have been stolen from the raffle is made, with the firemen becoming intent on discovering who is responsible for stealing the prizes – turning the ball into something which resembles a witchhunt.

The Firemen’s Ball was the last film Forman made in Czechoslovakia. Dina Iordanova argues that the picture is ‘much closer to the absurd and the satirical’ than Forman’s earlier films, and as a consequence ‘comes across as a biting satire on inept social organisation and mismanagement’ (Iordanova, 2003: 99). This led to a perception of the film as an allegorical assault on the Communist regime and an interpretation that ‘the men in charge are not only incompetent to run the show but are not even capable of taking care of their own line of business’ (ibid.). In judging the beauty contest, for example, the firemen allow their decisions to be impacted by the promise of bribery and by simple persuasion; the experience that they use as the benchmark which determines their authority to judge this contest is nothing more than an encounter with a photograph of the Miss World lineup. When one of the girls promises to strip to her bathing suit, the committee of firemen judging the beauty contest lock the door as if something illicit is taking place; as the young woman lifts her dress over her head, the firemen look at one another in astonishment. ‘Why didn’t you tell them all to wear bathing suits?’, the chairman of the committee asks quietly. ‘We never thought of it’, Franta responds. The Communists denounced the film for what they claimed was its sneering representation of its working class characters, though it’s easy to speculate that what offended them was the film’s apparent suggestion that the ruling party were both inept and corrupt. Following the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968, The Firemen’s Ball was banned in Czechoslovakia for this reason – and listed as ‘banned forever’, along with Vojtech Jasny’s All My Compatriots (1968), Evald Schorm’s End of a Priest (1968) and The Party and the Guests (Jan Nemec, 1966). Ironically, the film’s wealthy Italian producer Carlo Ponti reputedly disliked the film for the same reason, complaining that Forman risked alienating his potential audience by mocking (as Ponti saw it) the working classes. Shortly after the film’s release, Forman emigrated.  Mandana Taban and Michelle Woods have suggested that Czech New Wave films benefitted internationally from ‘the political upheavals of the time’ (the Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact invasion), which led to the pictures finding an audience and accompanying acclaim outside Czechoslovakia (Taban & Woods, 2007: 104). In their intention to show Czech society in an ‘uncensored’ manner, using the paradigms of neo-realism, the Czech New Wave films were often inherently – if not explicitly – political. Within this context, and given the film’s content, The Firemen’s Ball has often been interpreted as an allegory for the political situation within Czechoslovakia. The film’s depiction of the ineffectual, amateur firemen who are masquerading as professionals (and also as beauty pageant judges) – unable to put out a fire, judge a beauty contest without hiccups, or to ensure that the raffle prizes aren’t stolen from right under their noses – may be interpreted as a criticism of the Czech government. However, Forman resisted this interpretation of the film, suggesting that ‘to read a film as only political was ideologically motivated and too reductive, limiting it to polemics rather than art’ (ibid.). For Forman, the picture ‘universally concerned “the individual’s helplessness against the Establishment”’ (Liehm, quoted in ibid.). Forman argued that The Firemen’s Ball was ‘no allegory: it’s about real people, and for real people’ (Forman, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). However, Forman has since reworked his position, suggesting that he was cognisant of the film’s potential to be interpreted politically (Forman, cited in ibid.). Mandana Taban and Michelle Woods have suggested that Czech New Wave films benefitted internationally from ‘the political upheavals of the time’ (the Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact invasion), which led to the pictures finding an audience and accompanying acclaim outside Czechoslovakia (Taban & Woods, 2007: 104). In their intention to show Czech society in an ‘uncensored’ manner, using the paradigms of neo-realism, the Czech New Wave films were often inherently – if not explicitly – political. Within this context, and given the film’s content, The Firemen’s Ball has often been interpreted as an allegory for the political situation within Czechoslovakia. The film’s depiction of the ineffectual, amateur firemen who are masquerading as professionals (and also as beauty pageant judges) – unable to put out a fire, judge a beauty contest without hiccups, or to ensure that the raffle prizes aren’t stolen from right under their noses – may be interpreted as a criticism of the Czech government. However, Forman resisted this interpretation of the film, suggesting that ‘to read a film as only political was ideologically motivated and too reductive, limiting it to polemics rather than art’ (ibid.). For Forman, the picture ‘universally concerned “the individual’s helplessness against the Establishment”’ (Liehm, quoted in ibid.). Forman argued that The Firemen’s Ball was ‘no allegory: it’s about real people, and for real people’ (Forman, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). However, Forman has since reworked his position, suggesting that he was cognisant of the film’s potential to be interpreted politically (Forman, cited in ibid.).

The film is uncut and runs for 73:12 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 19Gb of space on its disc, this 1080p presentation of The Firemen’s Ball (using the AVC codec) is presented in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.37:1. In comparison with the presentation of the film released by Criterion on DVD in the States, Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation opens up the framing slightly, including a sliver of extra detail on the top, left and right-hand edges of the frame and a very slight sliver less detail on the bottom edge. The 4k restoration, supervised by the film’s cinematographer Miroslav Ondricek in 2012, exhibits a warmer colour temperature than the presentation of the film on the Criterion DVD release, giving the photography a warm, golden hue. (An excellent piece about the restoration of the film can be found here, at the Association of Czech Cinematographers’ website.) The film’s exhibition prints were apparently on East German ORWOcolor stock; the palette of ORWO’s colour film stocks were quite different to those of, for example, Kodak’s colour film stocks. ORWOcolor stock reputedly had a tendency to push whites towards cream and contain a yellow-cyan cast to the image. An ORWOcolor print was used as a reference and Ondricek ‘made the final assessment [as to the grading] during a calibrated screening’ of the picture (see the above-linked article from the ACC). Taking up approximately 19Gb of space on its disc, this 1080p presentation of The Firemen’s Ball (using the AVC codec) is presented in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.37:1. In comparison with the presentation of the film released by Criterion on DVD in the States, Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation opens up the framing slightly, including a sliver of extra detail on the top, left and right-hand edges of the frame and a very slight sliver less detail on the bottom edge. The 4k restoration, supervised by the film’s cinematographer Miroslav Ondricek in 2012, exhibits a warmer colour temperature than the presentation of the film on the Criterion DVD release, giving the photography a warm, golden hue. (An excellent piece about the restoration of the film can be found here, at the Association of Czech Cinematographers’ website.) The film’s exhibition prints were apparently on East German ORWOcolor stock; the palette of ORWO’s colour film stocks were quite different to those of, for example, Kodak’s colour film stocks. ORWOcolor stock reputedly had a tendency to push whites towards cream and contain a yellow-cyan cast to the image. An ORWOcolor print was used as a reference and Ondricek ‘made the final assessment [as to the grading] during a calibrated screening’ of the picture (see the above-linked article from the ACC).

The restoration was based predominantly on the film’s negative, though for some footage which on the negative was damaged irreparably, an interpositive was used in its stead. The presentation of the film on this disc is rich and detailed, with a very strong level of fine detail throughout. Excellent shadow detail is on display: the contrast levels are very good here, and the encode is excellent, ensuring the presentation has the rich, organic texture of 35mm film. This, combined with the strong, formal and painterly compositions within the original photography ensures that the presentation of the film on this disc is very pleasing. The restoration revealed that the onscreen title, appearing on some prints, which acted as a disclaimer to explain that the film wasn’t intended to offend firemen, wasn’t part of the original picture and was added at a later stage – so that title is absent in this presentation.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track (in Czech) which is rich and dynamic – evidenced from the get-go with the brass band music which opens the film. This is accompanied by optional English subtitles which are clear and easy to read, and free from any grammatical errors or issues with syntax.

Extras

The disc includes:  - a short piece about the restoration of the film (2:21). - a short piece about the restoration of the film (2:21).

- an appreciation by David Sorfa (32:37). Sorfa discusses the Czech New Wave as a context for The Firemen’s Ball, though as Sorfa argues Forman was older than most of the filmmakers associated with that particular movement – and consequently Forman ‘wasn’t as close to all of these people as they were to each other’. The Firemen’s Ball was made after A Blonde in Love, which made an impact outside Czechoslovakia and attracted international attention to Forman. The response to The Fireman’s Ball, which was criticised by the communists for supposedly ‘ridiculing the working class’ and was despised by producer Carlo Ponti for poking fun at ‘the common man’, helped push Forman away from the Czech film industry and towards America. Sorfa spends a great deal of time examining the importance of the theme of performance and performativity for Forman’s work generally, and specifically for The Fireman’s Ball. This, Sorfa argues, originates in Forman’s first love: the theatre. Forman’s films are about ‘acting’ and performativity which is combined with an emphasis on realism, and this – for Sorfa – defines Forman’s output and unifies both his Czech films and his American pictures. - New Wave Faces (31:27). In this fascinating piece, Michael Brooke offers a discussion of the non-professional actors who became associated with the Czech New Wave. - Archive interviews from the 2011 television series Golden Sixties. These interviews are all in Czech, with optional English subtitles and are with: -- Milos Forman (11:24). Forman discusses the origins of the film and praises, especially, Ondricek’s photography. (Ondricek apparently forbade the actors from wearing blue shirts in order to ensure an element of diversity within the palette of the film.) Forman also reveals that he never storyboards his films, on the principle that he doesn’t ‘adapt reality to my vision’ but rather ‘adapt[s] the camera to reality’. -- Ivan Passer (5:41). The film’s co-writer talks about some of the incidents which inspired the film and also reflects on the politics surrounding Ponti’s involvement as the film’s producer. -- Miroslav Ondricek (9:31). Ondricek examines his approach to photography. He suggests that today, ‘technology has basically stripped the camera function of its power’ because ‘you can touch up a film in post-production’. The Firemen’s Ball was originally to have been shot in black and white, and filming it in a single space demanded the necessity to shoot portraits. Ondricek studied painting to determine how best to shoot these portraits in colour. In addition to this, ‘all cold tones’ were eliminated from the film’s set and the photography, and the entire film was shot on a combination of a 25mm lens and a 75mm lens – a methodology which Ondricek has used in many of his films. Retail copies also include Arrow’s usual reversible sleeve artwork.

Overall

The Firemen’s Ball is a hugely entertaining film, dryly funny and highly satirical. Arrow’s presentation of the film is impressive and a big improvement over the previously-available DVD releases. The film itself is also accompanied by some very good contextual material. In all, it’s a very pleasing release. The Firemen’s Ball is a hugely entertaining film, dryly funny and highly satirical. Arrow’s presentation of the film is impressive and a big improvement over the previously-available DVD releases. The film itself is also accompanied by some very good contextual material. In all, it’s a very pleasing release.

References: Iordanova, Dina, 2003: Cinema of the Other Europe: The Industry and Artistry of East Central European Film. London: Wallflower Press Kockel, Ullrich, 2015: A Companion to the Anthropology of Europe. London: John Wiley and Sons Sultanik, Aaron, 1986: Film: A Modern Art. London: Cornwall Books Taban, Mandana & Woods, Michelle, 2007: ‘Analogy and Translatability in Iranian and Czech New Wave Films’. In: Kelly, Stephen & Johnston, David (eds), 2007: Betwixt and Between: Place and Cultural Translation. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 93-107

|

|||||

|