|

The Film

Kijū Yoshida: Love + Anarchism

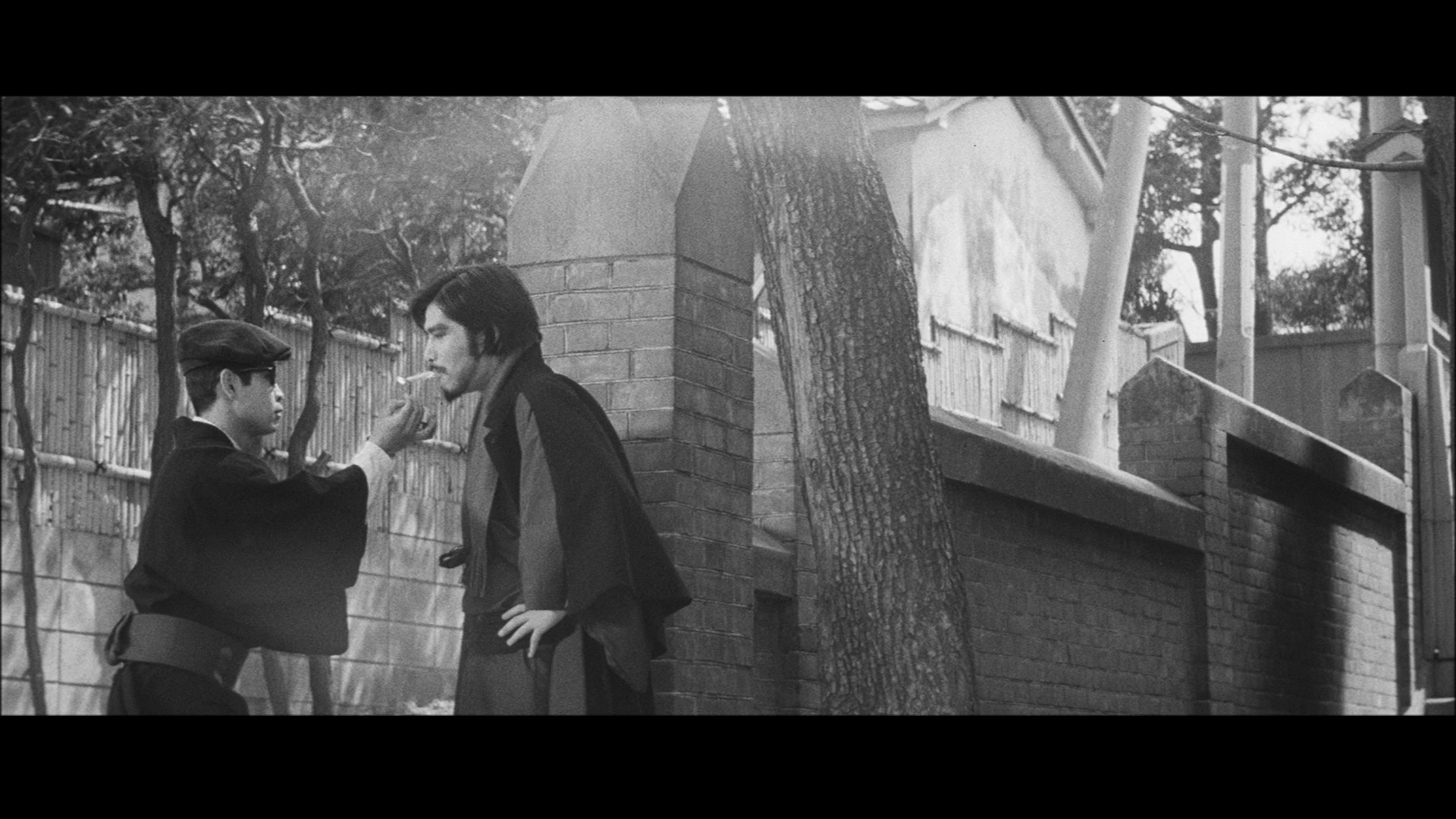

Yoshida Yoshishige, known more widely as Yoshida Kijū, is one of the key filmmakers associated with the Japanese New Wave, alongside Oshima Nagisa. Yoshida began his career making socially-minded youth-oriented films (seishun eiga) for Shochiku Studios, beginning with his first picture as a director, Good for Nothing (1960), which focused on a group of youngsters who live lives characterised by ennui. Two of these youths are from privileged families; the other two are from less privileged backgrounds, and discover that to compete with their more privileged counterparts they are forced into crime. From a similar thematic stable to Oshima’s contemporaneous second feature Cruel Story of Youth/Naked Youth (1960), Good for Nothing – together with Yoshida’s subsequent film Blood is Dry (1960) – established Yoshida’s unconventional approach to photography and mise-en-scène, which would become emphasised in his later films. Inviting comparisons with films of the various European New Waves of the era – especially a picture such as Jean-Luc Godard’s A bout de souffle/Breathless (1959), which has a similar focus on youth and crime – Yoshida’s films feature crisp monochrome photography dominated by a chiaroscuro lighting, soundtracks filled with jazz music, and an expressionistic approach to framing and composition. After the mid-1960s, like Oshima, Yoshida severed his ties with Shochiku and became a completely independent filmmaker, making films which featured strong political themes and married these to experimental photography and an avant-garde approach to narrative. Yoshida Yoshishige, known more widely as Yoshida Kijū, is one of the key filmmakers associated with the Japanese New Wave, alongside Oshima Nagisa. Yoshida began his career making socially-minded youth-oriented films (seishun eiga) for Shochiku Studios, beginning with his first picture as a director, Good for Nothing (1960), which focused on a group of youngsters who live lives characterised by ennui. Two of these youths are from privileged families; the other two are from less privileged backgrounds, and discover that to compete with their more privileged counterparts they are forced into crime. From a similar thematic stable to Oshima’s contemporaneous second feature Cruel Story of Youth/Naked Youth (1960), Good for Nothing – together with Yoshida’s subsequent film Blood is Dry (1960) – established Yoshida’s unconventional approach to photography and mise-en-scène, which would become emphasised in his later films. Inviting comparisons with films of the various European New Waves of the era – especially a picture such as Jean-Luc Godard’s A bout de souffle/Breathless (1959), which has a similar focus on youth and crime – Yoshida’s films feature crisp monochrome photography dominated by a chiaroscuro lighting, soundtracks filled with jazz music, and an expressionistic approach to framing and composition. After the mid-1960s, like Oshima, Yoshida severed his ties with Shochiku and became a completely independent filmmaker, making films which featured strong political themes and married these to experimental photography and an avant-garde approach to narrative.

The films that Yoshida made between 1965 and 1973 are connected by, aside from their political themes and experimental photography, the presence of Yoshida’s wife, Mariko Okada. A recognisable ‘star’, Okada has previously worked with Ozu, Mizoguchi and Naruse. The three films collected in Arrow’s new Blu-ray boxed set are from this era of Yoshida’s filmography. Chronologically, the films are: Eros + Massacre (1968), Yoshida’s film which juxtaposes the story of anarchist Sakae Ōsugi and feminist Noe Itō with the then-present; Heroic Purgatory (1969), which focuses on the radical student movements; and Coup d’état (also known as Martial Law, 1973), a film that examines the relationship between the ultranationalist writer Kita Ikki and the ‘2-26 Incident’: a pro-emperor military coup, inspired by Kita’s writings, that was attempted in 1936, an event which led to Kita’s arrest and execution.

Heroic Purgatory focuses on an engineer, Shoda, and his wife Kanako. The lives of this couple are disrupted by the appearance of a young woman, Ayu. Ayu claims that Shoda is her father. Ayu’s arrival heralds the appearance of a number of men who claim to be her father. This event causes Shoda to reflect on his past as a militant youth, the mysterious ‘Plan D’ which involves the abduction of ‘Ambassador J’, and also carries us into the future – to 1980, where Shoda and his wife are interrogated by the press in a kaleidoscopical sequence which seems almost like something concocted by Fellini. Heroic Purgatory focuses on an engineer, Shoda, and his wife Kanako. The lives of this couple are disrupted by the appearance of a young woman, Ayu. Ayu claims that Shoda is her father. Ayu’s arrival heralds the appearance of a number of men who claim to be her father. This event causes Shoda to reflect on his past as a militant youth, the mysterious ‘Plan D’ which involves the abduction of ‘Ambassador J’, and also carries us into the future – to 1980, where Shoda and his wife are interrogated by the press in a kaleidoscopical sequence which seems almost like something concocted by Fellini.

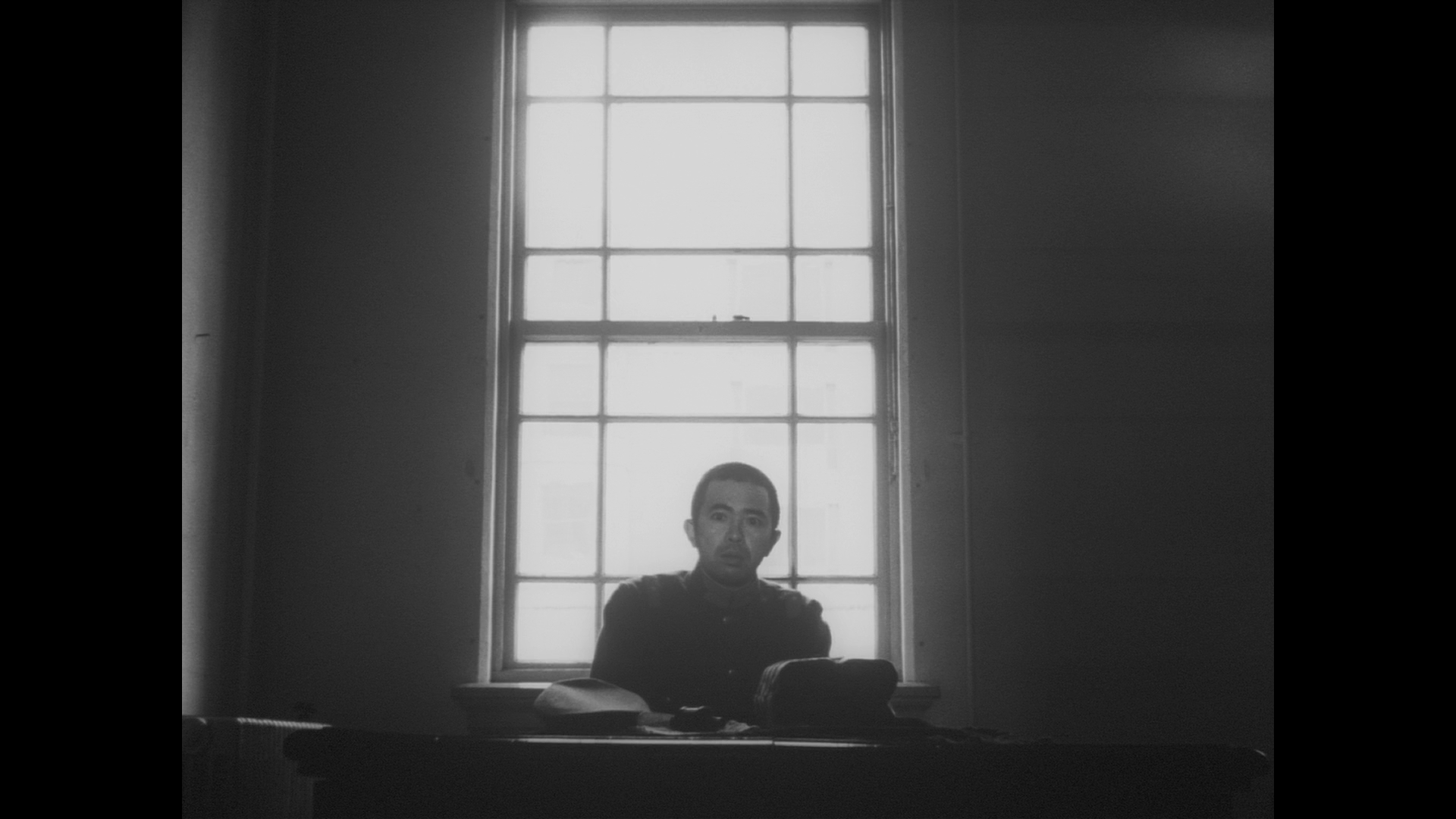

In contrast, Coup d’état has a much more ‘concrete’ approach to its narrative, though comprehension of the events taking place perhaps depends on the viewer’s familiarity with the historical events on which the film is based. The picture begins with a young man, Asahi Heido, murdering an elderly man, later revealed to be Yasuda Zenjiro, the head of the Yasuda financial cartel. Shortly after, revolutionary writer Kita Ikki receives a communiqué from Asahi in which Asahi claims to have acted on the ideas presented in one of Kita’s books, ‘Outline Plan for the Reorganisation of Japan’. A disciple of Kita’s, Nishida Mitsuki, coordinates a cabal of military and naval officers with the aim of assassinating the Prime Minister and the Minister of Interior. Whilst Kita is on the periphery of this uprising, having no direct part in it, following its failure he is arrested and executed.

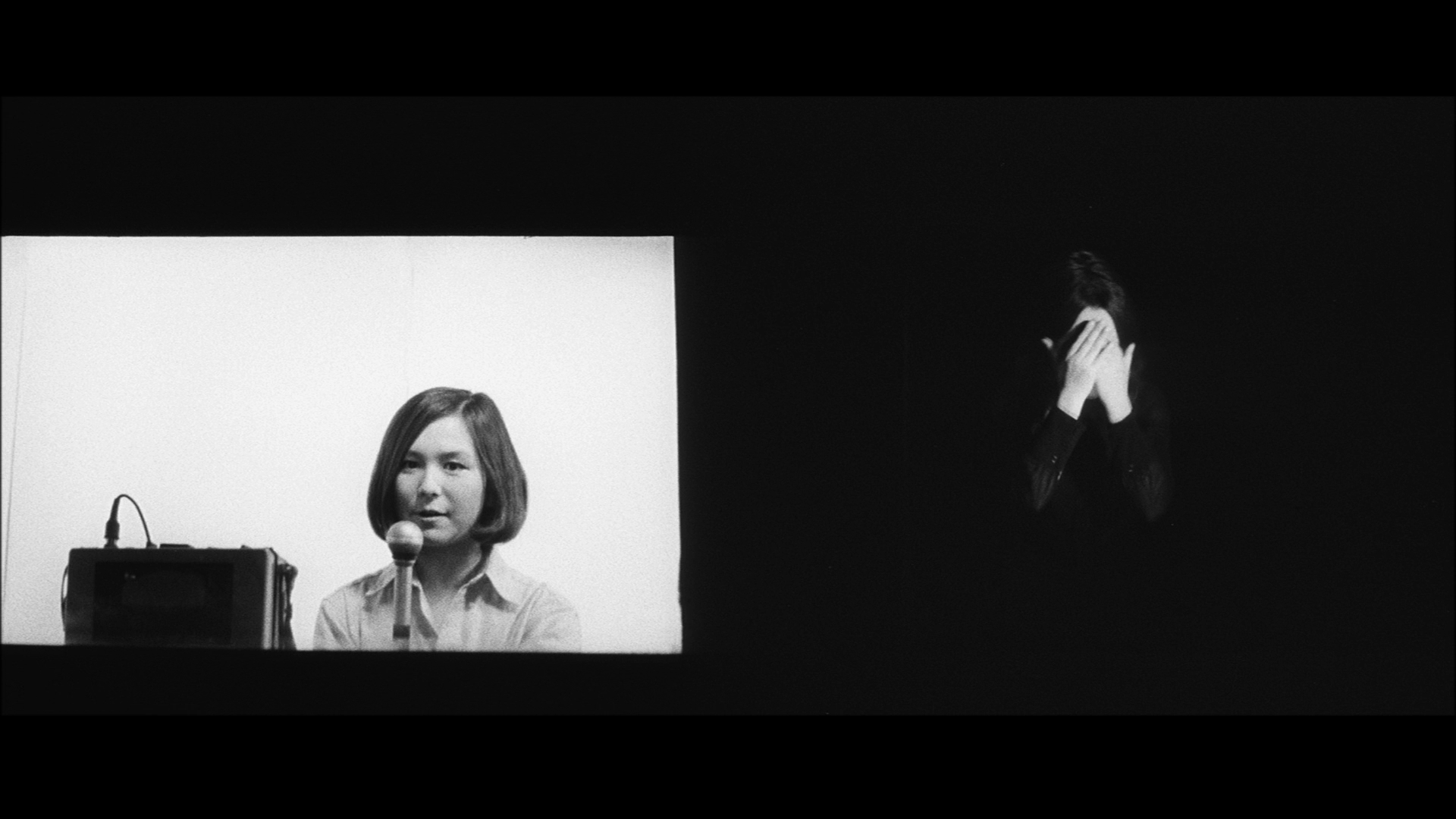

Eros + Massacre begins with a Eiko, a 20 year old student at Tokyo Design College, interviewing Mako, the daughter of Itō Noe, the Japanese anarchist and feminist of the Taishō era. The film juxtaposes the past with the present: Itō’s life, and her relationship with the anarchist Ōsugi Sakae, is intercut with scenes depicting Eiko’s life and that of her compatriot Wada. Interested in the ideas of Itō and Ōsugi, Eiko researches their lives and practises Ōsugi’s principle of ‘free love’, and her free-spirited approach to her own sexuality leads to her being investigated by a detective who believes her to be a prostitute. In some sequences, the past bleeds into the present, with characters from the past appearing in scenes set within the diegetic present.

Yoshida’s post-1965 pictures can be a daunting proposition for non-Japanese viewers. As Alexander Jacoby and Rea Armit state in the introduction to their interview with Yoshida for the Midnight Eye website, ‘his films are often difficult and demanding, and require some historical knowledge and awareness of Japanese society for full appreciation’ (Jacoby & Armit, 2010: np). However, this is mitigated by ‘their sensual beauty’ which ‘ought to be accessible to any sensitive viewer’ (ibid.). Yoshida’s post-1965 pictures can be a daunting proposition for non-Japanese viewers. As Alexander Jacoby and Rea Armit state in the introduction to their interview with Yoshida for the Midnight Eye website, ‘his films are often difficult and demanding, and require some historical knowledge and awareness of Japanese society for full appreciation’ (Jacoby & Armit, 2010: np). However, this is mitigated by ‘their sensual beauty’ which ‘ought to be accessible to any sensitive viewer’ (ibid.).

Yoshida stumbled into filmmaking with no overt desire to become a director: he claims that he was attracted to working at Shochiku on his father’s recommendation and that ‘I didn't enter Shochiku because I was devoted to films’ but because ‘they had a very good salary system’ (Yoshida, quoted in Jacoby & Armit, op cit.: np). Yoshida was more inspired by foreign films than by popular Japanese cinema, and ‘for me, if I had any idea about making films, it was from an entirely different cinematic world view than the one that Shochiku had in mind, and probably not only Shochiku, but in Japan of that time as a whole’ (Yoshida, quoted in ibid.). Yoshida parted ways with Shochiku because he felt that the studio was ‘not so enthusiastic about my films anymore, and I thought that my pictures were not exactly normal Shochiku product, and that this was maybe not the best place from me to work on making my films’ (Yoshida, quoted in ibid.).

Comparisons have often been drawn between Yoshida’s films and those of Michelangelo Antonioni. The films of both Yoshida and Antonioni revolve around themes of ennui and alienation. Jacoby suggests that the difference between the work of these two directors lies in their approach to this material: Antonioni’s films ‘chart […] the enervation and emotional sterility of the wealthy classes’, whereas the abiding focus of Yoshida’s post-1965 films is on ‘bourgeois women possessed by feelings of destructive intensity’ (Jacoby, 2013: np). Where Antonioni’s films are constructed through ‘measured, meditative camera movements’, Yoshida’s pictures feature ‘fragmented editing and rapid, wheeling tracks and pans’ that ‘reflect the inner turmoil of his heroines’ (ibid.).

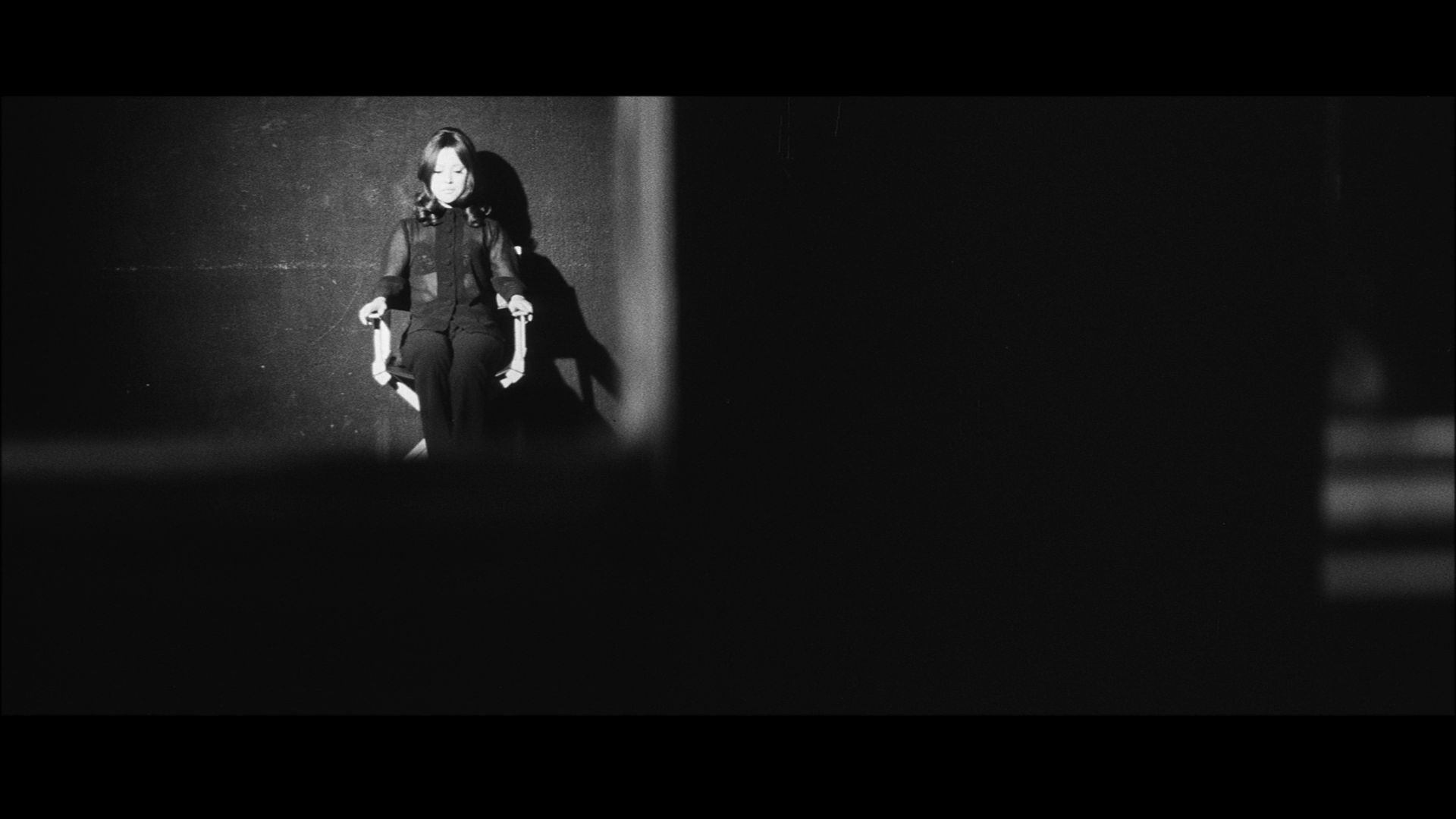

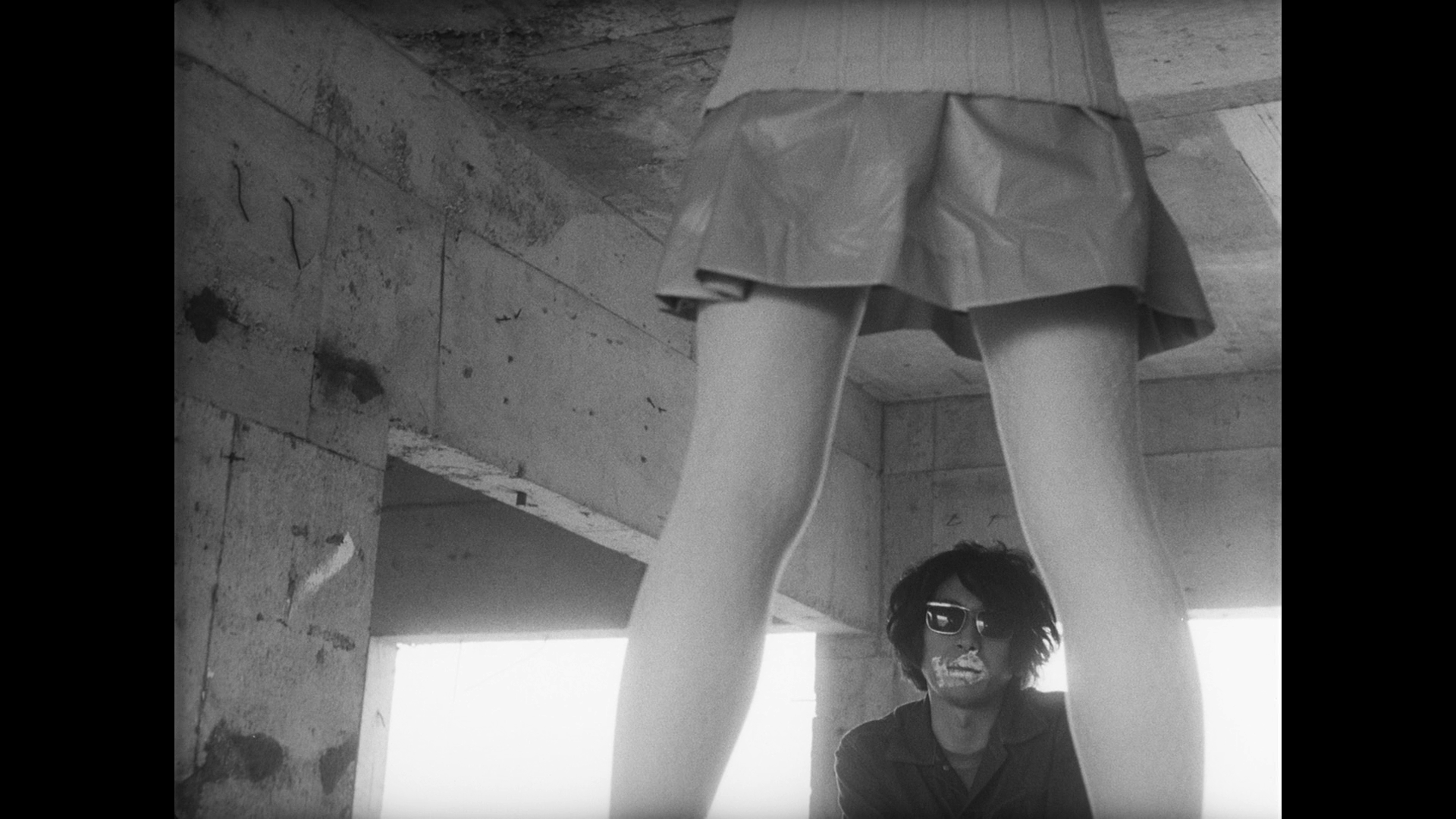

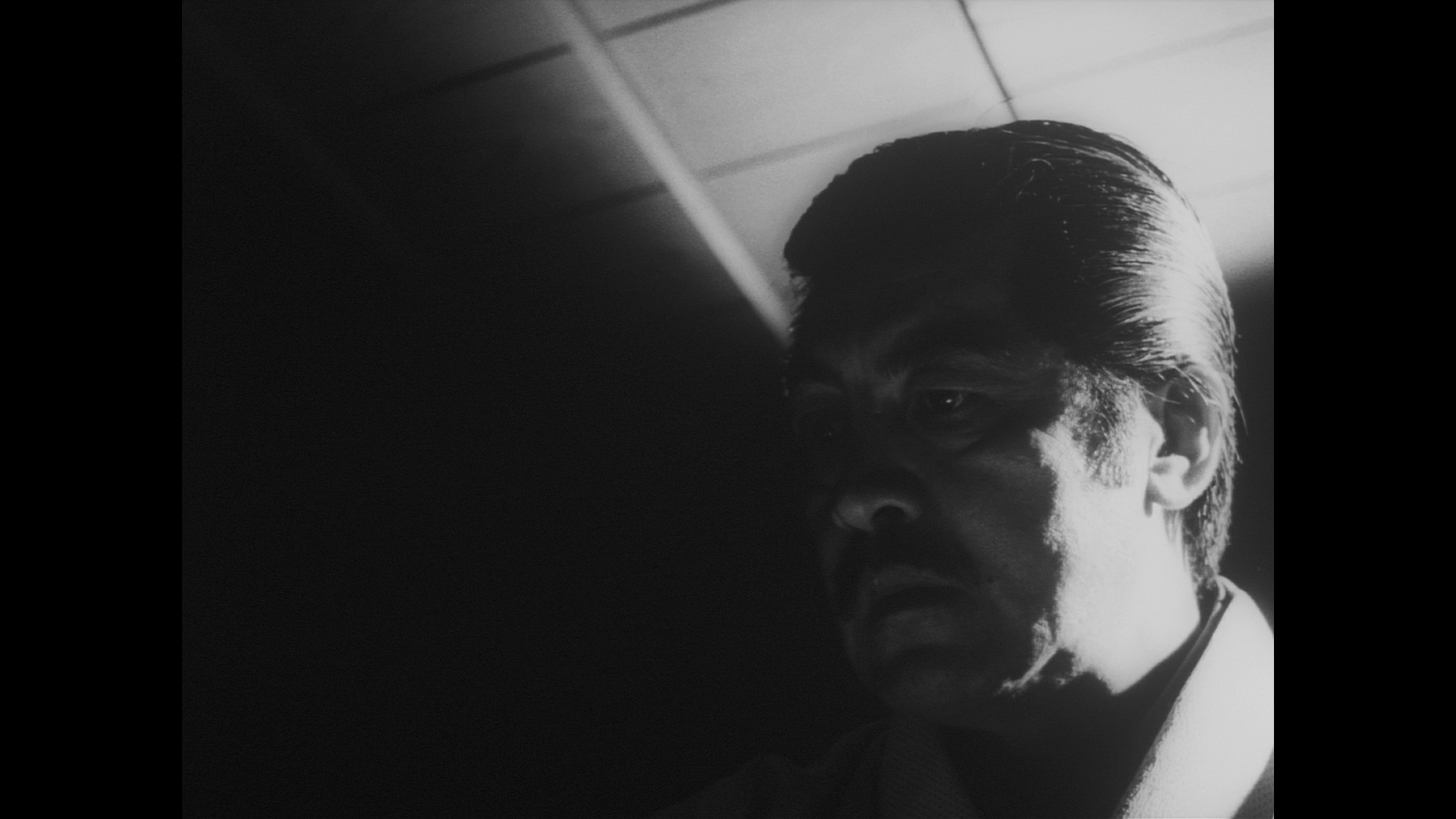

There’s a poetic quality to the films, with the tendency in both Heroic Purgatory and Eros + Massacre (especially the former) to present sequences whose diegetic function is weaker than their poetic function. The films are dominated by unusual compositions. Heroic Purgatory begins with shots of a parking garage in which a sense of unease is generated by the framing of the shots. In the opening shot, two thirds of the image are dominated by the roof of the garage as a young woman walks towards the camera, diminished in the frame by the composition. Similar compositions recur throughout all three of the films, suggesting a cold, alienating relationship between the characters in these films and the urban environments in which they live. This is reinforced in the opening sequence of Eros + Massacre, in which Eiko interviews Mako, and the two are shown in a series of disorientating compositions which refuse to offer a balanced image for the audience. There’s a poetic quality to the films, with the tendency in both Heroic Purgatory and Eros + Massacre (especially the former) to present sequences whose diegetic function is weaker than their poetic function. The films are dominated by unusual compositions. Heroic Purgatory begins with shots of a parking garage in which a sense of unease is generated by the framing of the shots. In the opening shot, two thirds of the image are dominated by the roof of the garage as a young woman walks towards the camera, diminished in the frame by the composition. Similar compositions recur throughout all three of the films, suggesting a cold, alienating relationship between the characters in these films and the urban environments in which they live. This is reinforced in the opening sequence of Eros + Massacre, in which Eiko interviews Mako, and the two are shown in a series of disorientating compositions which refuse to offer a balanced image for the audience.

In these films, and especially in Eros + Massacre (which draws direct parallels between the Taisho era and the then-present day, even allowing the past and the present to bleed together at certain points in the narrative), Yoshida is arguing – according to Isolde Standish – ‘that the legacies of defeat – such as the ideological anarchy experienced by the post-war generation around the turmoil of political and intellectual divisions associated with the opposition to the implementation of the Subversive Activities Prevention Law, the student movements and the 1968 Anpo struggle – were not dissimilar to the state of the Left in Japan after the High Treason incident of 1910’ (Standish, 2011: 61). Standish suggests that this is heightened by the perception amongst ‘the Left’ of the time that the Subversive Activities Prevention Law was simply a ‘reinstatement’ of the 1925 Peace Preservation Law. Certainly, the films focus on a theme of rebellion (closely allied with youth) and repression.

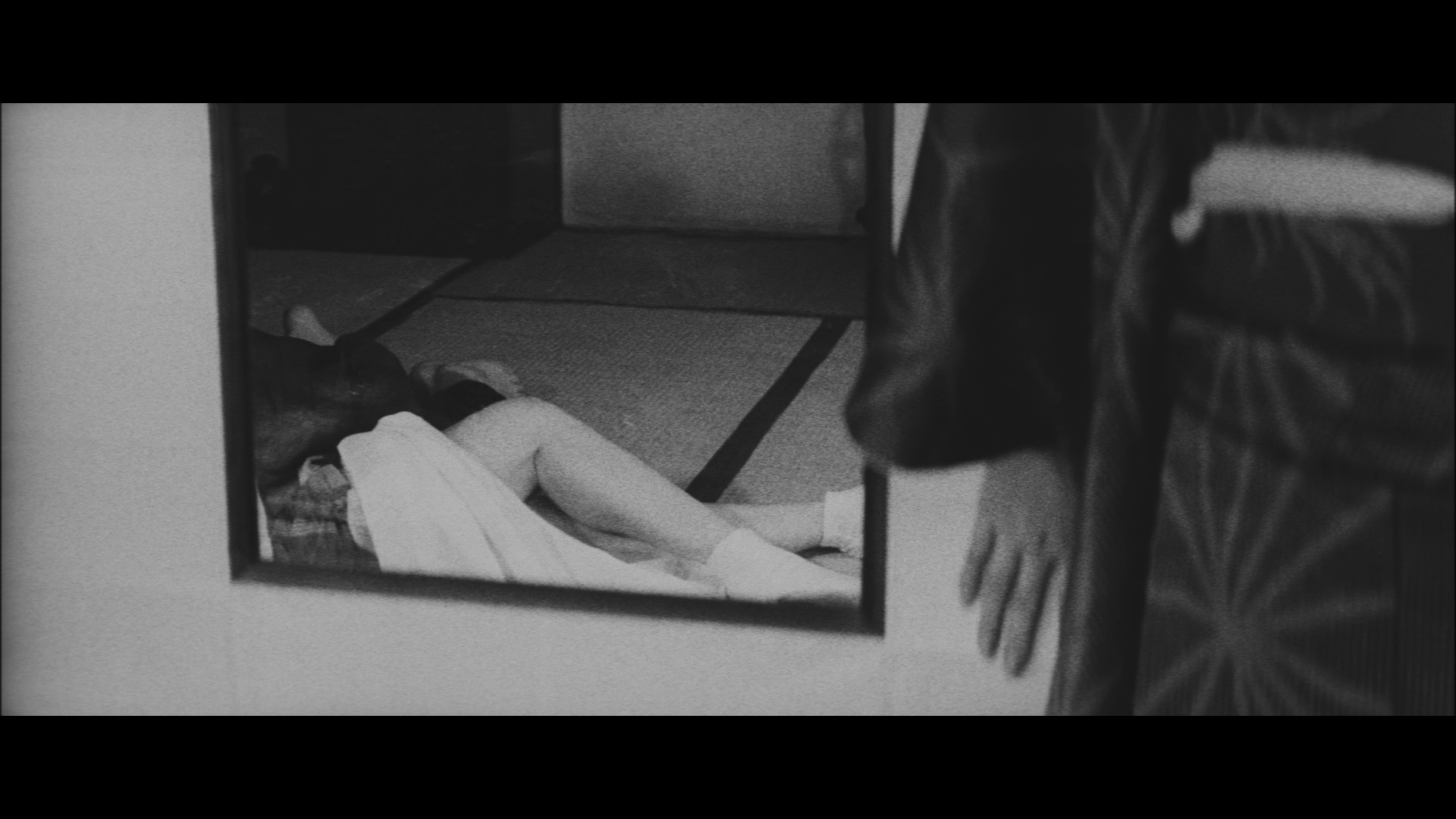

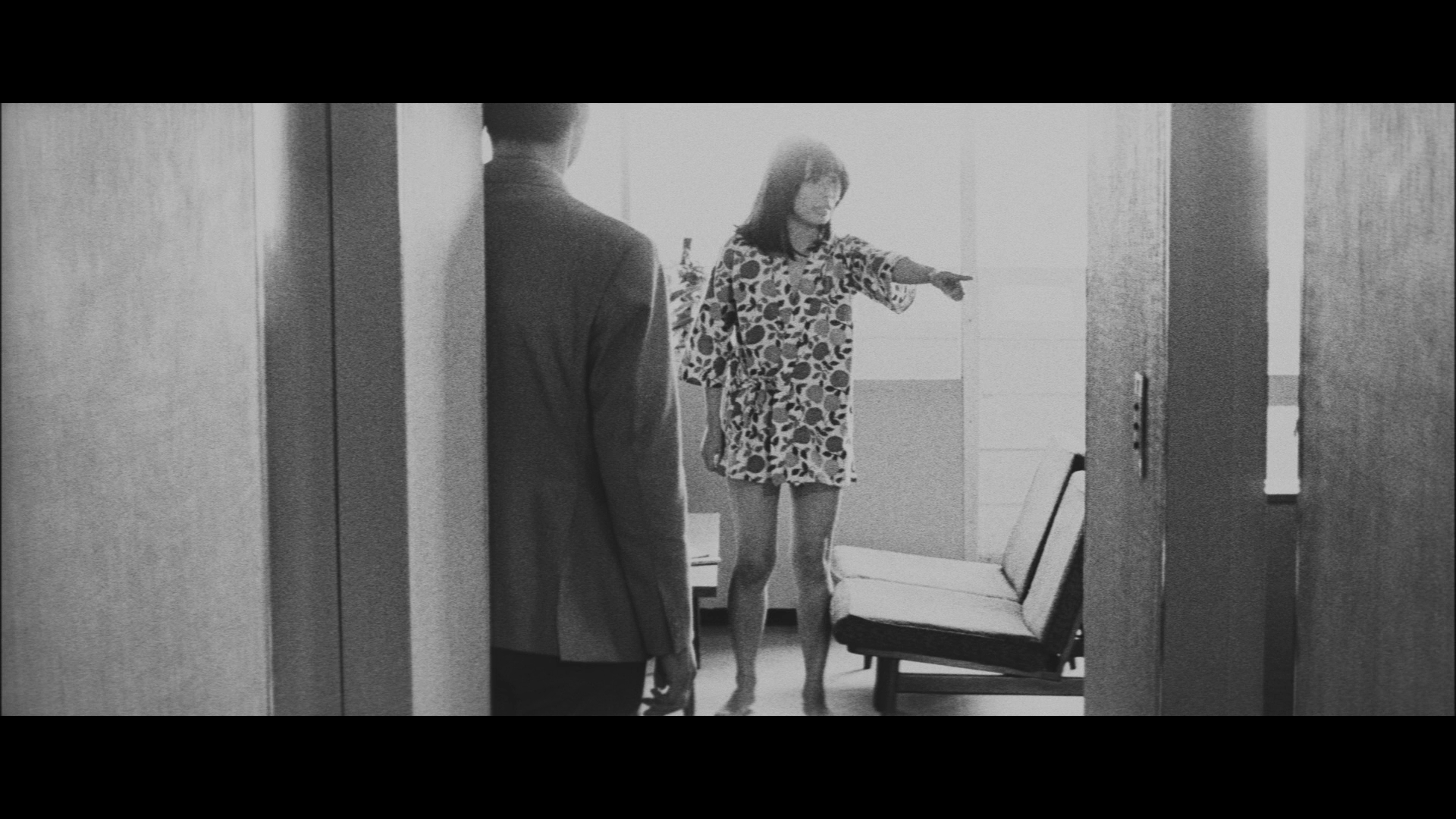

Yoshida has claimed that a ‘crucial aspect’ of his work for Shochiku and beyond is his conceptualisation of ‘youth [as] necessarily a destructive force. Or youth is something that is really impossible. The idea that youth is a splendid thing, as they show in commercials, is merely an illusion, this is how I thought then and still, actually, think today’ (Yoshida, quoted in Jacoby & Armit, op cit.: np). In the films included in this set, this ethos is shown most clearly in Heroic Purgatory, with its depiction of radical youth movements; but it’s also evident within Eros + Massacre, which contains a depiction of the ennui of youth which is connected within the film with displays of ‘empty’ sexuality – as if the sexuality grows out of boredom, intended as a way of alleviating this ennui, but actually exacerbates it. Eiko practices the principle of ‘free love’ espoused by Ōsugi, and following her interview with Mako she is next introduced in a hotel room, where she is shown naked whilst one of her lovers kisses and caresses her buttocks. The very fact that Eiko is turned away from her lover allows us to see her bored response to his caresses: she is utterly disinterested in what is taking place. Wada interrupts this scene and watches; the participants are unfazed by his presence. Following this, a rugby game is shown on screen, overlaid with the sounds of Eiko climaxing, the combination of sound and image suggesting an equation of violence and sexuality. Yoshida then cuts to a scene which reveals Eiko to be masturbating in the shower, her actions an index of her frustrations – both sexual and social. In this context, Ōsugi’s later comment within the film, ‘Even love kills freedom between us’, gains added resonance. Yoshida has claimed that a ‘crucial aspect’ of his work for Shochiku and beyond is his conceptualisation of ‘youth [as] necessarily a destructive force. Or youth is something that is really impossible. The idea that youth is a splendid thing, as they show in commercials, is merely an illusion, this is how I thought then and still, actually, think today’ (Yoshida, quoted in Jacoby & Armit, op cit.: np). In the films included in this set, this ethos is shown most clearly in Heroic Purgatory, with its depiction of radical youth movements; but it’s also evident within Eros + Massacre, which contains a depiction of the ennui of youth which is connected within the film with displays of ‘empty’ sexuality – as if the sexuality grows out of boredom, intended as a way of alleviating this ennui, but actually exacerbates it. Eiko practices the principle of ‘free love’ espoused by Ōsugi, and following her interview with Mako she is next introduced in a hotel room, where she is shown naked whilst one of her lovers kisses and caresses her buttocks. The very fact that Eiko is turned away from her lover allows us to see her bored response to his caresses: she is utterly disinterested in what is taking place. Wada interrupts this scene and watches; the participants are unfazed by his presence. Following this, a rugby game is shown on screen, overlaid with the sounds of Eiko climaxing, the combination of sound and image suggesting an equation of violence and sexuality. Yoshida then cuts to a scene which reveals Eiko to be masturbating in the shower, her actions an index of her frustrations – both sexual and social. In this context, Ōsugi’s later comment within the film, ‘Even love kills freedom between us’, gains added resonance.

The dialogue in the films is elliptical and often openly symbolic. ‘I’m lost’, Ayu says near the start of Heroic Purgatory. ‘Once you understand you’re lost, you’re no longer lost’, she is told, ‘You can return to where you came from. You can ask your way too. In other words, you have a destination’. The film itself begins with Shoda dictating a dream to his secretary over the sound of the clacking typewriter in his office, ‘This morning, when I lifted the mat there were three cockroaches. I put them in an empty instant coffee can and filled it with boiling water. I had to drink it, while everyone was looking at me’. Elsewhere, the rhetoric of revolution spills through the screen: in Coup d’état, following the murder of Yasuda by Asahi, Kita Ikki receives a message from Asahi which states, ‘Always guard my principles without words, without clamour, without denunciations. In silence, stab, slash, cut, shoot. Between friends, there is no need for pacts. It’s enough to kill one person. Do your best. The time for revolution is ripe. If we can foment revolution in many places, it will not be difficult to obtain support’. Elsewhere in that film, Kita asserts that ‘All great men are revolutionaries. Revolutionaries are not just those men that bring about the revolution but those that support it’. Speaking with Daiki, the young son of a Chinese revolutionary, Kita explains his ideology: ‘This is our world’, he says. ‘There are so many people and everyone does what they believe is right [….] They’re not right at all! They all act separately, lacking any coordination, and in their incoherence they feel uneasy [….] You may realise that you’re making a mistake, but you never now how you’re making it’. Kita continues to suggest that ‘martial law does not provide people with structure; it casts out structure that is embedded in the disorder of mankind. And people shall notice [….] the order that resides within them. And then, perhaps, they will stop and look to the skies so as to make sure that martial law has created order within them [….] In this way, our revolution will be realised’. The dialogue in the films is elliptical and often openly symbolic. ‘I’m lost’, Ayu says near the start of Heroic Purgatory. ‘Once you understand you’re lost, you’re no longer lost’, she is told, ‘You can return to where you came from. You can ask your way too. In other words, you have a destination’. The film itself begins with Shoda dictating a dream to his secretary over the sound of the clacking typewriter in his office, ‘This morning, when I lifted the mat there were three cockroaches. I put them in an empty instant coffee can and filled it with boiling water. I had to drink it, while everyone was looking at me’. Elsewhere, the rhetoric of revolution spills through the screen: in Coup d’état, following the murder of Yasuda by Asahi, Kita Ikki receives a message from Asahi which states, ‘Always guard my principles without words, without clamour, without denunciations. In silence, stab, slash, cut, shoot. Between friends, there is no need for pacts. It’s enough to kill one person. Do your best. The time for revolution is ripe. If we can foment revolution in many places, it will not be difficult to obtain support’. Elsewhere in that film, Kita asserts that ‘All great men are revolutionaries. Revolutionaries are not just those men that bring about the revolution but those that support it’. Speaking with Daiki, the young son of a Chinese revolutionary, Kita explains his ideology: ‘This is our world’, he says. ‘There are so many people and everyone does what they believe is right [….] They’re not right at all! They all act separately, lacking any coordination, and in their incoherence they feel uneasy [….] You may realise that you’re making a mistake, but you never now how you’re making it’. Kita continues to suggest that ‘martial law does not provide people with structure; it casts out structure that is embedded in the disorder of mankind. And people shall notice [….] the order that resides within them. And then, perhaps, they will stop and look to the skies so as to make sure that martial law has created order within them [….] In this way, our revolution will be realised’.

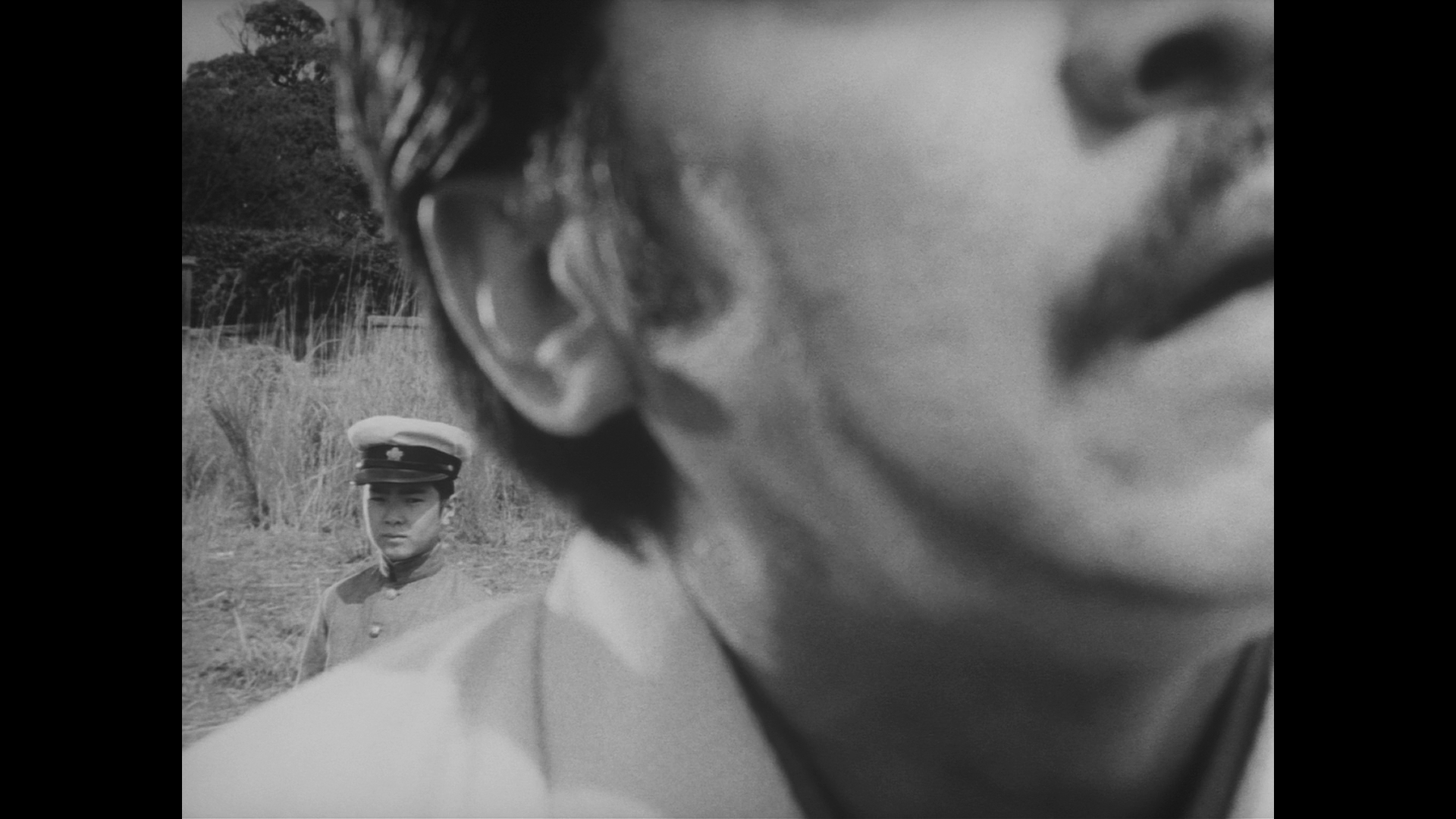

Heroic Purgatory begins with atonal music which, combined with the unusual compositions, suggests an abstract depiction of trauma. (The effect is strikingly similar to that achieved in Sidney Lumet’s later British film The Offence, 1972, in which Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music ensures a near-consistent level of unease within the viewer.) Similar music, even more jarring considering the historical context of the narrative within the film, features in Coup d’état: in a scene which seems to confirm Kita’s prophecy, that people ‘will stop and look to the skies so as to make sure that martial law has created order within them’, we are presented with the image of a young soldier walking along the street, observing people looking towards the skies. This moment is accompanied on the soundtrack by discordant electronic music that would seem more at home within a horror picture, and which clashes with the film’s temporal setting (1936). Heroic Purgatory begins with atonal music which, combined with the unusual compositions, suggests an abstract depiction of trauma. (The effect is strikingly similar to that achieved in Sidney Lumet’s later British film The Offence, 1972, in which Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music ensures a near-consistent level of unease within the viewer.) Similar music, even more jarring considering the historical context of the narrative within the film, features in Coup d’état: in a scene which seems to confirm Kita’s prophecy, that people ‘will stop and look to the skies so as to make sure that martial law has created order within them’, we are presented with the image of a young soldier walking along the street, observing people looking towards the skies. This moment is accompanied on the soundtrack by discordant electronic music that would seem more at home within a horror picture, and which clashes with the film’s temporal setting (1936).

Coup d’état is the most coherent of the films, and certainly the most ‘concrete’, though there’s some assumption of the viewer’s cognisance of the historical events depicted within the narrative. In its depiction of the revolution inspired by Kita, the film is reminiscent of Paul Schrader’s later biopic of Mishima Yujio, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985). The similarity is perhaps unsurprising, given that Yoshida was apparently partly inspired in his approach to the story of Kita by the then-current circumstances surrounding Mishima’s failed coup attempt and his death. Noel Burch notes that ‘the active, historically informed response demanded by such a film is significantly rare in the cinema of the Western capitalist world’, though there are echoes of Yoshida’s approach in more recent films such as Uli Edel’s The Baader-Meinhof Complex (2008) and Olivier Assayas’ Carlos the Jackal (2010) (Burch, 1979: 350).

During the production of Coup d’état, Yoshida underwent an operation in which a tumour was removed from his stomach, which led to delays in shooting the film. When the film was completed, Yoshida had to spend some time recuperating, and he found that he spent the next five years abroad. Following Coup d’état, Yoshida didn’t make another film for thirteen years, and to some extent, despite their narrative differences, the three films within this boxed set represent a coherent unit. In terms of their ambiguities, their melding of past and present, truth and fiction, the films’ approach is arguably underscored in a key exchange within Eros + Massacre. In that film, the detective who investigates Eiko for prostitution tells Eiko that, ‘You think your life is a disaster. You can’t bear living without a goal. But life has no objective. It’s a life of sorrow. The only sure thing is death [….] So we live in the imagination’. He continues to ask, ‘What is the power of imagination? Poor people’s delusions. Not having money, their imagination grow stronger. They dream of revolution’. During the production of Coup d’état, Yoshida underwent an operation in which a tumour was removed from his stomach, which led to delays in shooting the film. When the film was completed, Yoshida had to spend some time recuperating, and he found that he spent the next five years abroad. Following Coup d’état, Yoshida didn’t make another film for thirteen years, and to some extent, despite their narrative differences, the three films within this boxed set represent a coherent unit. In terms of their ambiguities, their melding of past and present, truth and fiction, the films’ approach is arguably underscored in a key exchange within Eros + Massacre. In that film, the detective who investigates Eiko for prostitution tells Eiko that, ‘You think your life is a disaster. You can’t bear living without a goal. But life has no objective. It’s a life of sorrow. The only sure thing is death [….] So we live in the imagination’. He continues to ask, ‘What is the power of imagination? Poor people’s delusions. Not having money, their imagination grow stronger. They dream of revolution’.

Heroic Purgatory is presented uncut with a running time of 118:06 mins. Coup d’état is similarly complete and runs for 109:50 mins. Eros + Massacre is presented in both its originally-released theatrical cut, running 165:17 mins, and its much longer director’s cut, which runs for 206:25 mins.

The difference between Eros + Massacre’s theatrical cut and the director’s cut lies in its treatment of Kamichika Ichiko, one of Ōsugi’s lovers. After the film was completed, Kamichika threatened the filmmakers with legal action over her depiction within the film. As a consequence, the film was cut by around 55 minutes, removing her character almost completely from the theatrical cut (where, for her brief appearance, she was renamed ‘Masaoka Ichiko’).

Video

All of the films were shot on 35mm monochrome film. The presentations of the films in this set are based on restorations that were supervised by Yoshida himself. The two cuts of Eros + Massacre – the theatrical cut (running 165:17 mins) and the director’s cut (running 206:25 mins) – are included on separate discs, whilst Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’état are contained on one disc. All of the films were shot on 35mm monochrome film. The presentations of the films in this set are based on restorations that were supervised by Yoshida himself. The two cuts of Eros + Massacre – the theatrical cut (running 165:17 mins) and the director’s cut (running 206:25 mins) – are included on separate discs, whilst Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’état are contained on one disc.

The theatrical cut of Eros + Massacre, on disc one, takes up approximately 41Gb of space on its disc. On disc two, the director’s cut of Eros + Massacre takes up 44Gb of space on its disc; on disc three, Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’état each take up a little over 20Gb of space each.

Eros + Massacre is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The presentation is clean and clear of damage and debris, with a very strong level of detail. There are some interesting differences between the theatrical cut and the director’s cut, with the latter having a slightly brighter appearance and more defined contrast. The theatrical cut was sourced from a film print, whereas the director’s cut was apparently taken from a source closer to the film’s negative. The appearance of the director’s cut is closer to the intentions of Yoshida; the theatrical cut has a more muted aesthetic, by comparison. As in Heroic Purgatory, there are many shots in which the characters are filmed against glaring backdrops and shots that are deliberately overexposed, with highlights that are intentionally burnt out; this is a characteristic of the original photography that is heightened in the director’s cut of Eros + Massacre, which also features some interesting use of handheld cameras and obtuse compositions, together with many shots of (and through) glass and reflective objects. Both the theatrical cut and the director’s cut of the picture benefit from robust encodes that ensure the presentations have the organic texture of 35mm film.

Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’état are presented in their original aspect ratios of 1.37:1. Heroic Purgatory has a much more crisp, high contrast appearance, with some shots deliberately overexposed (as in Eros + Massacre). It’s a visually disorientating film, with many shots through glass surfaces (windows, tables). The presentation on this disc is very good. Coup d’état is again crisp and clear, with some very minor damage present here and there. A very strong level of detail is present, and the presentation demonstrates nicely-balanced contrast levels; the photography here is much more low-contrast than either Heroic Purgatory and Eros + Massacre, and on the whole the film has a very different, much more ‘concrete’, aesthetic. The presentations of both films feature strong, pleasing encodes, and both features exhibit the texture of 35mm film. Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’état are presented in their original aspect ratios of 1.37:1. Heroic Purgatory has a much more crisp, high contrast appearance, with some shots deliberately overexposed (as in Eros + Massacre). It’s a visually disorientating film, with many shots through glass surfaces (windows, tables). The presentation on this disc is very good. Coup d’état is again crisp and clear, with some very minor damage present here and there. A very strong level of detail is present, and the presentation demonstrates nicely-balanced contrast levels; the photography here is much more low-contrast than either Heroic Purgatory and Eros + Massacre, and on the whole the film has a very different, much more ‘concrete’, aesthetic. The presentations of both films feature strong, pleasing encodes, and both features exhibit the texture of 35mm film.

NB. Some larger screen grabs of all three films are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

All three films feature LPCM 1.0 mono tracks (in Japanese, naturally). These are clean and clear throughout. (The sounds of insects on the audio track of Coup d’état are particularly striking, as is the film’s electronic score.) There’s some very minor distortion in the audio track for Heroic Purgatory, a flutter that hits some of the dialogue in the film, but it certainly won’t impair one’s enjoyment of the film.

All three films feature optional English subtitles. These are easy to read and free of issues.

Extras

DISC ONE: Eros + Massacre: Theatrical Cut DISC ONE: Eros + Massacre: Theatrical Cut

- ‘Yoshida ...or: The Explosion of the Story’ (30:10). This documentary about Eros + Massacre features input from Mathieu Capel and Jean Douchet. The documentary explores Yoshida’s relationship with other filmmakers associated with the Japanese New Wave and the impact that this movement had on Japanese cinema. Yoshida’s approach to making his post-1965 pictures is discussed. There’s a close discussion of Eros + Massacre and Yoshida’s representation of the events on which the film is based. Yoshida is also interviewed about his work and approach. The documentary is in French and Japanese, with optional English subtitles

- Introduction by David Desser (11:21). Desser, the author of a key book about the Japanese New Wave, which takes its title from Eros + Massacre, provides an introduction to the picture. Desser suggests that Eros + Massacre is Yoshida’s masterpiece for three reasons: the depth of the film’s narrative, which is facilitated by the film’s length; the experimental visual style; the ‘overinterest in history and politics’. Desser discusses the film’s depiction of the two time frames represented within its narrative, and its intercutting of these two eras.

- Commentaries by David Desser. Desser offers commentary on some specific scenes from Eros + Massacre:

-- ‘Taisho’ (6:50)

-- ‘Politics’ (5:26)

-- ‘Free Love’ (4:59)

-- ‘Confrontations’ (6:39)

-- ‘Earthquake’ (11:24)

-- ‘Walking’ (5:27)

-- ‘Directions’ (7:39)

-- ‘Ending’ (8:46)

- Theatrical Trailer (3:30).

DISC TWO: Eros + Massacre: Director’s Cut DISC TWO: Eros + Massacre: Director’s Cut

- Introduction by David Desser (9:08). In this introduction to the director’s cut, Desser talks about the differences between this longer version of the film and the shorter theatrical cut, discussing the controversy that arose owing to the film’s depiction of Kamichika Ichiko.

- Commentaries by David Desser. Desser provides commentary over selected scenes from the director’s cut of the film. These include:

-- ‘Rugby’ (2:01)

-- ‘A Doll’s House’ (3:11)

-- ‘Sister’ (2:56)

-- ‘Godardian Absurdity’ (9:32)

-- ‘Knife’ (3:18)

-- ‘Caught’ (9:30)

-- ‘Bluestocking’ (4:09)

-- ‘Sleep’ (2:43)

-- ‘Knifing’ (14:19)

DISC THREE: Heroic Purgatory and Coup d’état

Heroic Purgatory

- Introduction by Yoshida (6:08). Yoshida discusses the fallout of the Korean War and the divisions within Japanese society during the 1950s and 1960s. During Yoshida’s youth ‘there was an element within the Communist Party’ that ‘insisted on an armed struggle’; this film is an attempt to capture that culture. ‘Revolution always shifts to armed struggle. The end of revolution is armed struggle […] It’s a contradiction of justice. No matter how beautiful the static ideology is, it’s unavoidable as politics involve power’, Yoshida reasons. With Eros + Massacre, Yoshida ‘wanted to live in the past’, but Heroic Purgatory is about ‘look[ing] at the present from the future’. The interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- Introduction by David Desser (9:14). Desser describes this film as ‘the most demanding and political, perhaps even the most frustrating’ of the three films included in this boxed set. Desser attempts to answer the question ‘What is this movie about?’ He offers some contextual background for the film by exploring some of the tensions within post-war Japan. Yoshida depicts the Communist Party as ‘near-Stalinist’, and ‘takes a dim […] view of politics, especially political violence’. The picture ‘refuses a stable time frame’ and a clear delineation between past, present and future.

- Commentaries by David Desser. These are commentaries over selected scenes from the film. These include:

‘Opening’ (3:04)

‘Death?’ (1:58)

‘Conflation’ (10:54)

‘Molestation’ (2:51)

‘Blackmail’ (2:20)

‘Ritsuko’ (5:25)

‘Tension’ (3:45)

‘Trial’ (4:30)

‘1980’ (8:19)

‘Interviewers’ (4:08)

- Trailer (3:03)

Coup d’état Coup d’état

- Introduction by Yoshida (5:22). Yoshida discusses the film’s origins in the 2-26 Incident of 1936, ‘the day that Japane experience its only coup d’etat’. He discusses the symbolic importance of the incident, which led to a shift within Japan towards militarism and accelerated the path to war. He discusses the ideas of Kita Ikki and the agenda within Kita’s work: Kita was ‘different’ in calling ‘for a revolution for the Emperor’ rather than against Hirohito. This is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- Introduction by David Desser (8:50). Desser discusses some of the differences between this film and Yoshida’s previous three pictures. He provides some details about the 2-26 Incident, which puts some of the events within the film’s narrative in context. Kita ‘was not a direct participant in the coup’, but was executed in 1937 owing to the perception that his influence on the officers who staged the coup ‘was so great’ that he represented a threat to society. Desser also discusses the influence of Mishima on this specific film.

- Commentaries by David Desser. These, again, are scene specific commentaries by Desser. The scenes include:

-- ‘Chanting’ (9:24)

-- ‘Slogans’ (2:22)

-- ‘Plans’ (3:20)

-- ‘Crying’ (1:26)

-- ‘Razor’ (5:15)

-- ‘Coup’ (4:54)

-- ‘Arrest’ (9:15)

- Trailer (2:58)

Also included within retail copies of the boxed set is an 80 page book which features new writing about the films by Desser, Standish and Dick Stegewerns.

Overall

The films contained within this package are challenging and thought-provoking. There’s a remarkable consistency of theme and approach within these three films – or four, if one counts the two cuts of Eros + Massacre as separate entities. The focus on rebellion, youth and sexuality shines through and connects the films with their immediate social context. Around these themes, Yoshida weaves unconventional narratives which can be confusing to a casual viewer but which reward repeated viewings. In many ways, watching the films is like peeling away the many layers of an onion. The films contained within this package are challenging and thought-provoking. There’s a remarkable consistency of theme and approach within these three films – or four, if one counts the two cuts of Eros + Massacre as separate entities. The focus on rebellion, youth and sexuality shines through and connects the films with their immediate social context. Around these themes, Yoshida weaves unconventional narratives which can be confusing to a casual viewer but which reward repeated viewings. In many ways, watching the films is like peeling away the many layers of an onion.

Arrow’s new HD presentations of all three pictures are impressive, and the films themselves are complemented by some absolutely superb contextual material. This release is a delight and comes with a very strong recommendation.

References:

Berra, John (ed), 2012: Directory of World Cinema: Japan. London: Intellect Books

Burch, Noel, 1979: To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in

the Japanese Cinema. University of California Press

Jacoby, Alexander, 2013: A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors. California: Stone Bridge Press

Jacoby, Alexander & Armit, Rea, 2010: ‘Yoshishige Yoshida’. [Online.] http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/yoshishige-yoshida/

Standish, Isolde, 2011: Politics, Porn and Protest: Japanese Avant-Garde Cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. London: Continuum

Eros + Massacre: Director’s Cut

Eros + Massacre: Theatrical Cut

Heroic Purgatory

Coup d’etat

|