|

|

Blood Rage AKA Slasher AKA Nightmare at Shadow Woods (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th November 2015). |

|

The Film

Blood Rage (John Grissmer, 1987) Blood Rage (John Grissmer, 1987)

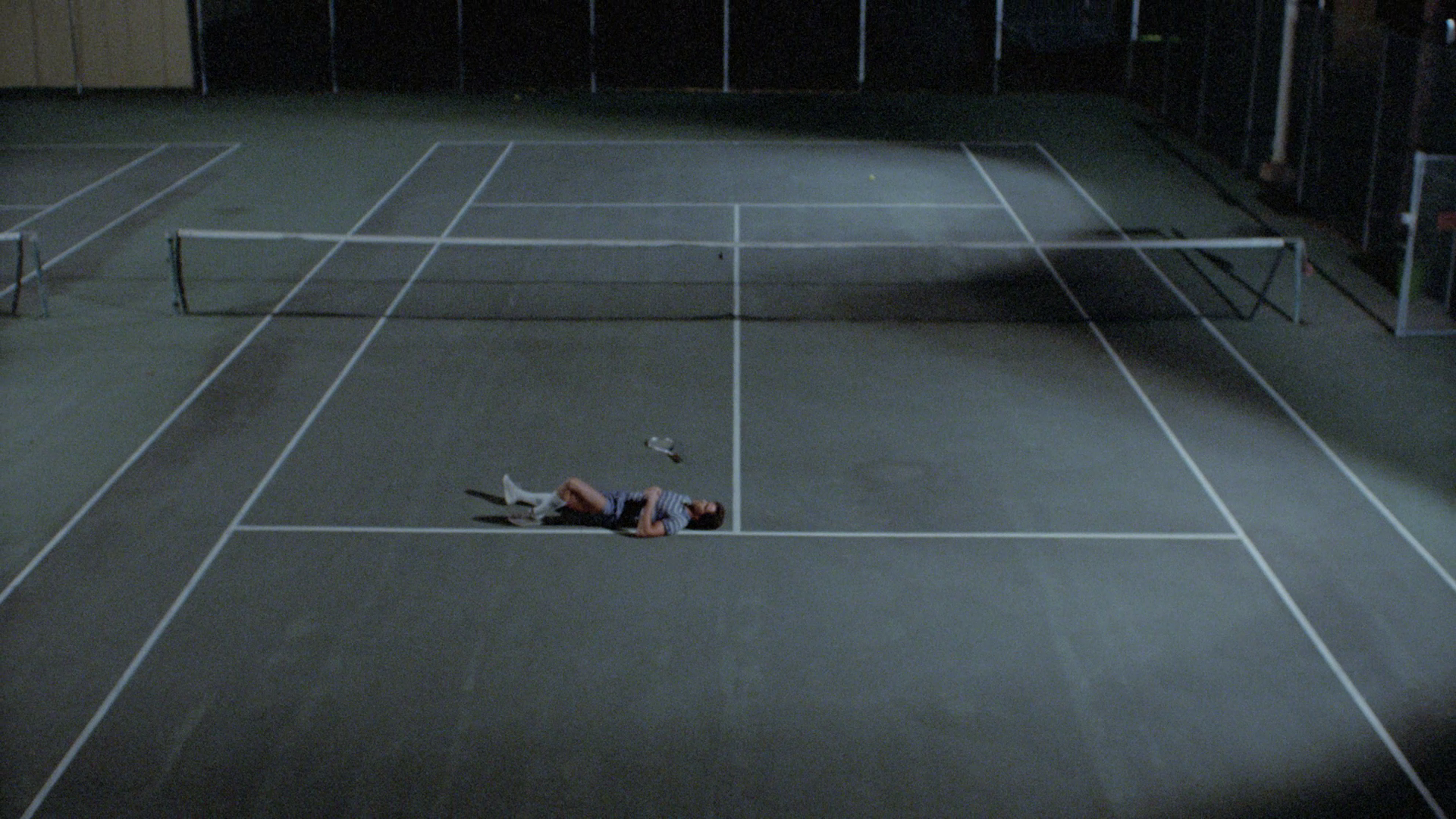

Made in 1983 but not given a widespread cinema release in the US until 1987, Blood Rage has been known under a number of titles. (It is also sometimes confused with the Joseph Zito directed 1981 slasher film Bloodrage, to add to the confusion.) The original title seems to have been Slasher, which is the title that the main presentation of the picture on this Blu-ray release contains. In 1987, the film was released to cinemas in America under the title Nightmare at Shadow Woods, in reference to the apartment complex (Shadow Woods Apartments) which forms the locus of the narrative. Beginning in 1974 in Jacksonville, Florida, Blood Rage opens with single mother Maddy Simmons (Louise Lasser) at a drive-in with her new lover. As Maddy and her lover are in an embrace, Maddy’s twin sons, Terry and Todd, are (apparently) asleep in the back of the vehicle. Unbeknownst to their mother, the boys awaken and sneak out of the car. They approach another vehicle in which a young couple are making love; unexpectedly, Terry murders the male of the couple with a hand axe, burying the tool in the man’s skull. Ten years later, having been incorrectly blamed for the murder committed by his twin, Todd (Mark Soper) is still being held within a psychiatric institution, under the care of Dr Berman (Marianne Kanter, who also produced the film); meanwhile, his twin brother Terry (also played by Mark Soper) lives an outwardly normal life as a college student, residing with Maddy in Shadow Woods Apartments. Maddy is engaged to the owner of Shadow Woods, Brad. Maddy and Terry’s lives are disrupted by news that Todd has escaped from Dr Berman’s institution and is returning to Shadow Woods. Terry takes this as an opportunity to go on another killing spree, committing a series of brutal murders of the residents of Shadow Woods, which Maddy takes as confirmation of the guilt of her ‘wayward’ son Todd  The opening sequence is quietly effective in establishing the film’s abrupt shifts in tone, from broad comedy to brutal violence. The film begins with external shots of the Jacksonville drive-in as, on the soundtrack, we hear unsettling music that resembles the avant-garde strings-based orchestrations by Krzystof Penderecki (from his opera The Devils of Loudon) that appear in the prologue of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) and which accompany Father Merrin’s vision of evil in Iraq. In Blood Rage, however, this unsettling aural assault quickly segues to disco-type synth music as we are taken inside the lobby of the drive-in, where patrons buy their tickets, and then inside the men’s lavatories where an entrepreneurial sort (played by Ted Raimi) sells black market condoms that are pinned to the inside of his jacket in the manner one might associate with a wartime spiv. The opening sequence is quietly effective in establishing the film’s abrupt shifts in tone, from broad comedy to brutal violence. The film begins with external shots of the Jacksonville drive-in as, on the soundtrack, we hear unsettling music that resembles the avant-garde strings-based orchestrations by Krzystof Penderecki (from his opera The Devils of Loudon) that appear in the prologue of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) and which accompany Father Merrin’s vision of evil in Iraq. In Blood Rage, however, this unsettling aural assault quickly segues to disco-type synth music as we are taken inside the lobby of the drive-in, where patrons buy their tickets, and then inside the men’s lavatories where an entrepreneurial sort (played by Ted Raimi) sells black market condoms that are pinned to the inside of his jacket in the manner one might associate with a wartime spiv.

The shifts in tone continue in the subsequent scene. From the condom salesman in the men’s lavatory, the film takes us outside, to the drive-in itself and into the car in which Maddy sits with her lover. They kiss. Maddy is reticent. The audience is suddenly made aware of the reason for her hesitation: the presence of her young sons Terry and Todd, apparently asleep in the back of the car. As Maddy and her lover are distracted, Terry and Todd awaken. ‘Mom’s at it again’, Terry whispers quietly to his brother, ‘Let’s get out of here’. The two boys sneak out of the vehicle and approach a car in which a naked man and woman are mid-coitus. Todd keeps his distance, but Terry nears the car. When the man’s attention is drawn to Terry, Terry attacks the man with an axe. It’s a graphic, brutal murder, rendered all the more effective by Ed French’s strong effects work. The girl runs away, naked and screaming. The murder takes place as Maddy’s lover tells her, ‘I don’t date women who drag their kids around everywhere’, connecting Maddy’s unsuccessful attempt to find a romantic partner and the boys’ witnessing of both their mother kissing her lover and the young couple having sex with the brutal murder, establishing an Oedipal subtext which runs throughout the film. The graphic killing that Terry perpetrates, which follows Todd and Terry’s witnessing of their mother kissing her lover and, shortly afterwards, the naked couple making love in their car (a possible metonym for the boys’ perception of their mother’s relationships with men), is framed as a Freudian primal scene – a moment to which the film’s later acts of violence refers, as if Terry is doomed to repeat it.  With obvious echoes of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), the murderous Terry’s relationship with his mother has strong Oedipal undertones. When Maddy announces her engagement to Brad, Terry exhibits jealousy and tries to destabilise Maddy and Brad’s relationship through mentioning Todd’s escape from the psychiatric institution. ‘Looks like you’re gonna get the chance to meet the rest of the family’, Terry taunts Brad, ‘My psychotic brother just escaped’. Upon learning of Todd’s escape from the institution, Terry picks Brad as his first victim; he attacks his would be step-father with a machete, lopping off his hand (which, after tumbling to the floor, bizarrely continues to clench and unclench around the can of drink that Brad was holding at the time). Later, when Todd encounters Maddy, who by that stage is in a drunken stupor and believes Todd to be Terry, he carries her to bed and she tells him to give his mother a kiss. She offers Todd her lips, and he kisses her lightly; the moment is held just long enough to be uncomfortable without making too explicit the suggestion that Maddy and Terry’s relationship is unhealthily close. This Oedipal subtext is given its payoff at the end of the picture. With obvious echoes of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), the murderous Terry’s relationship with his mother has strong Oedipal undertones. When Maddy announces her engagement to Brad, Terry exhibits jealousy and tries to destabilise Maddy and Brad’s relationship through mentioning Todd’s escape from the psychiatric institution. ‘Looks like you’re gonna get the chance to meet the rest of the family’, Terry taunts Brad, ‘My psychotic brother just escaped’. Upon learning of Todd’s escape from the institution, Terry picks Brad as his first victim; he attacks his would be step-father with a machete, lopping off his hand (which, after tumbling to the floor, bizarrely continues to clench and unclench around the can of drink that Brad was holding at the time). Later, when Todd encounters Maddy, who by that stage is in a drunken stupor and believes Todd to be Terry, he carries her to bed and she tells him to give his mother a kiss. She offers Todd her lips, and he kisses her lightly; the moment is held just long enough to be uncomfortable without making too explicit the suggestion that Maddy and Terry’s relationship is unhealthily close. This Oedipal subtext is given its payoff at the end of the picture.

Some of the techniques within the film are unusual and draw attention to themselves in an almost ‘meta’ way. Whether these techniques are intentionally ‘off’ or are instead simply the product of a naïve approach to filmmaking is open to debate. (Certainly, much of the humour within the film seems intentional, including the absurd excessiveness of the moments of violence – carried, as noted above, by some outstandingly visceral effects work – and almost pushes the film into the realm of self-parody.) For example, when Maddy visits Todd and Dr Berman in the psychiatric institution near the start of the film, the film incorporates narration from Dr Berman’s case notes; presented from a future perspective, in relation to the events being depicted visually, and reflecting on Maddy’s relationship with Todd, this narration offers a strange interpretation of events which suggests Berman’s objectivity towards Todd and Maddy whilst also highlighting Todd’s detachment from the world around him. Berman tells Maddy that Todd is slowly beginning to recall the events of the night of the murder at the drive-in, and his recollections are casting suspicion upon Terry. Maddy reacts extremely negatively to this news: ‘My children are not guinea pigs’, she protests angrily, ‘No more tests!’ This is followed by Dr Berman’s narration: ‘I wondered: how would she react when confronted with Todd himself’, Berman’s off-screen voice queries, ‘How would Todd react in view of his new recollections. I was not without worry. After all, I had never seen the two together [….] Maddy treated Todd like a child’, Berman continues, ‘as if no time had passed since the evening of the murder’. Berman’s narration reinforces Maddy’s insistence that Terry is innocent and her desire to rebuild ‘one big, happy family’.  Maddy’s apparent desperation to find a mate is mirrored in that of her younger neighbour. Karen babysits for this neighbour, looking after her very young child whilst the neighbour is out with her new boyfriend. The neighbour returns with her new beau and Karen departs; out of her boyfriend’s earshot, the neighbour tells her baby daughter that she has been out, trying to find the child a ‘rich daddy’. The film has earlier suggested that Maddy’s ‘irresponsible’ display of her sexuality with what seems to be a string of boyfriends has in some way caused Terry’s murderous behaviour; this seems to be mirrored in the neighbour’s similar attempts to find her child a ‘rich daddy’, suggesting a cycle of destructive relationships which cause lasting damage to the children of women like Maddy and her younger neighbour. (The film’s near-insistent association of single motherhood with ‘sluttish’ behaviour would be potentially offensive if it wasn’t presented in such an exaggerated manner.) Of course, Terry soon arrives and murders both the neighbour and her beau in a spectacularly brutal manner (decapitating the latter and leaving his severed head hanging outside the neighbour’s front door), orphaning the child. Later, after discovering Terry’s true nature, Karen flees from him and finds the bodies of the neighbour and her lover; Karen takes the baby with her and protects the child, offering a more ‘stable’ maternal presence than both Maddy and the neighbour combined. The film’s ‘final girl’ (to reference one of the defining paradigms of the ‘bodycount’/slasher film), Karen is left at the end of the picture literally holding the baby. Maddy’s apparent desperation to find a mate is mirrored in that of her younger neighbour. Karen babysits for this neighbour, looking after her very young child whilst the neighbour is out with her new boyfriend. The neighbour returns with her new beau and Karen departs; out of her boyfriend’s earshot, the neighbour tells her baby daughter that she has been out, trying to find the child a ‘rich daddy’. The film has earlier suggested that Maddy’s ‘irresponsible’ display of her sexuality with what seems to be a string of boyfriends has in some way caused Terry’s murderous behaviour; this seems to be mirrored in the neighbour’s similar attempts to find her child a ‘rich daddy’, suggesting a cycle of destructive relationships which cause lasting damage to the children of women like Maddy and her younger neighbour. (The film’s near-insistent association of single motherhood with ‘sluttish’ behaviour would be potentially offensive if it wasn’t presented in such an exaggerated manner.) Of course, Terry soon arrives and murders both the neighbour and her beau in a spectacularly brutal manner (decapitating the latter and leaving his severed head hanging outside the neighbour’s front door), orphaning the child. Later, after discovering Terry’s true nature, Karen flees from him and finds the bodies of the neighbour and her lover; Karen takes the baby with her and protects the child, offering a more ‘stable’ maternal presence than both Maddy and the neighbour combined. The film’s ‘final girl’ (to reference one of the defining paradigms of the ‘bodycount’/slasher film), Karen is left at the end of the picture literally holding the baby.

The confusion of Todd and Terry continues throughout the film, assisted by Mark Soper’s impressive performance(s) as the two twins: Soper invests Todd with a hangdog look, whilst he plays Terry as a lively, amiable all-American boy with a grin that’s just a little too insistent. (In some ways, a similarity can perhaps be drawn between Terry’s depiction of the ‘successful’, apparently well-liked Terry and his concealed psychopathy, and Christian Bale’s performance as Patrick Bateman in Mary Harron’s 2000 film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho.) Berman arrives at Shadow Woods with an assistant who wields a tranquilizer gun. The pair offer to protect Maddy and Terry from Todd, even though in her previous narration Dr Berman suggested that she believed Terry to be guilty of the murder that took place ten years prior and queried, ‘But who knows what will trigger [Terry to commit] another killing?’ Meanwhile, taking post outside the Simmons house and believing Todd to be hiding in the trees outside, Dr Berman’s assistant attempts to coax Todd out of his hiding place by promising him a marijuana cigarette(?) Of course, it isn’t Todd hiding in the trees; rather, it’s Terry. Terry attacks Berman’s assistant, running him through with the machete, and then Terry hunts down Dr Berman in the woods and, using the machete, cuts her in half(!) Terry then returns to Shadow Woods and cleans himself, licking the blood off his fingers and making the deadpan observation, ‘It’s not cranberry sauce’. (‘No shit, Sherlock’, is the observation that the viewer might be making at this point.) This bizarre line is repeated towards the end of the film, like a bad punchline that an equally bad comedian insists on returning to, in the hope that it will become funny simply through its repetition. The confusion of Todd and Terry continues throughout the film, assisted by Mark Soper’s impressive performance(s) as the two twins: Soper invests Todd with a hangdog look, whilst he plays Terry as a lively, amiable all-American boy with a grin that’s just a little too insistent. (In some ways, a similarity can perhaps be drawn between Terry’s depiction of the ‘successful’, apparently well-liked Terry and his concealed psychopathy, and Christian Bale’s performance as Patrick Bateman in Mary Harron’s 2000 film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho.) Berman arrives at Shadow Woods with an assistant who wields a tranquilizer gun. The pair offer to protect Maddy and Terry from Todd, even though in her previous narration Dr Berman suggested that she believed Terry to be guilty of the murder that took place ten years prior and queried, ‘But who knows what will trigger [Terry to commit] another killing?’ Meanwhile, taking post outside the Simmons house and believing Todd to be hiding in the trees outside, Dr Berman’s assistant attempts to coax Todd out of his hiding place by promising him a marijuana cigarette(?) Of course, it isn’t Todd hiding in the trees; rather, it’s Terry. Terry attacks Berman’s assistant, running him through with the machete, and then Terry hunts down Dr Berman in the woods and, using the machete, cuts her in half(!) Terry then returns to Shadow Woods and cleans himself, licking the blood off his fingers and making the deadpan observation, ‘It’s not cranberry sauce’. (‘No shit, Sherlock’, is the observation that the viewer might be making at this point.) This bizarre line is repeated towards the end of the film, like a bad punchline that an equally bad comedian insists on returning to, in the hope that it will become funny simply through its repetition.

Even Terry’s girlfriend Karen (Julie Gordon) mistakes Todd for her lover. Encountering Todd for the first time, she believes him to be Terry and tells him, ‘I love you a lot and, well, I want you to make love to me’. The shocked Todd responds by telling her, honestly, ‘I’m not Terry; I’m Todd [….] You seem nice. I’ve never kissed a girl before’. In response to this, Karen delivers the highly amusing line, ‘Oh, well, you really ought to try it sometime’, before running away. (Encountering her friends Artie, Gregg and Andrea, Karen tells them of her encounter with Todd and his declaration that he has ‘never kissed a girl before’. ‘Oh, how creepy’, Andrea asserts as if the very concept marks Todd as ‘deviant’.) At the climax of the film, this relationship is inverted: Karen becomes aware that Terry is the murderous brother, and she flees from him, encountering scene after scene of carnage involving her friends and neighbours as she seeks a hiding place.  As with many 1980s horror films, Blood Rage has been implicated in at least one real life act of violence, when in 1991 it was cited for its allegedly pivotal role in an Australian murder case; during the trial of the murderer, a criminal barrister asserted that ‘it is not easy to absolve a system which allows for such a violent and unmeritorious film as Nightmare at Shadow Woods to be viewed indiscriminately by members of the community regardless of their underlying problems or susceptibilities… it was a film with no discernible artistic merit at all… as far as I could see it was nothing more than a vehicle for depicting gratuitous, mindless and ghoulish violence’ (quoted in Cettl, 2013: 135). As if ironically commenting on the censorious mindset and validating the 18th Century satirist Reverend Sidney Smith’s famous declaration that ‘Men whose trade is ratcatching love to catch rats … and the suppressor is gratified by his vice’, Blood Rage features a sequence in which Terry – who at this point has already been revealed to be a cruel and callous murderer – watches a violent film on the television with Karen and observes dryly, ‘God, that’s horrible. How can they show that on TV?’ As with many 1980s horror films, Blood Rage has been implicated in at least one real life act of violence, when in 1991 it was cited for its allegedly pivotal role in an Australian murder case; during the trial of the murderer, a criminal barrister asserted that ‘it is not easy to absolve a system which allows for such a violent and unmeritorious film as Nightmare at Shadow Woods to be viewed indiscriminately by members of the community regardless of their underlying problems or susceptibilities… it was a film with no discernible artistic merit at all… as far as I could see it was nothing more than a vehicle for depicting gratuitous, mindless and ghoulish violence’ (quoted in Cettl, 2013: 135). As if ironically commenting on the censorious mindset and validating the 18th Century satirist Reverend Sidney Smith’s famous declaration that ‘Men whose trade is ratcatching love to catch rats … and the suppressor is gratified by his vice’, Blood Rage features a sequence in which Terry – who at this point has already been revealed to be a cruel and callous murderer – watches a violent film on the television with Karen and observes dryly, ‘God, that’s horrible. How can they show that on TV?’

Video

As noted above, Blood Rage was made in 1983 but didn’t get a cinema release until 1987, when it was retitled Nightmare at Shadow Woods. That version of the picture featured heavy trims to the film’s various moments of violence but included a few moments of exposition (principally, a discussion by Maddy’s neighbours about Todd and Terry at the Shadow Woods Apartments’ swimming pool, and a few additional shots of nudity). The film was then released on VHS as Blood Rage; this cut restored the violence to the film, but omitted the additional narrative footage that was included in the Nightmare at Shadow Woods edit. As noted above, Blood Rage was made in 1983 but didn’t get a cinema release until 1987, when it was retitled Nightmare at Shadow Woods. That version of the picture featured heavy trims to the film’s various moments of violence but included a few moments of exposition (principally, a discussion by Maddy’s neighbours about Todd and Terry at the Shadow Woods Apartments’ swimming pool, and a few additional shots of nudity). The film was then released on VHS as Blood Rage; this cut restored the violence to the film, but omitted the additional narrative footage that was included in the Nightmare at Shadow Woods edit.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of the film contains both the Nightmare at Shadow Woods and Blood Rage edits (with the latter bearing the onscreen title Slasher), and also includes a composite edit which includes the exclusive footage from both edits of the picture. Blood Rage (or 'Slasher') has been restored in 2k from the original negative; the presentation of Nightmare at Shadow Woods is essentially a ‘rebuild’ of that cut of the picture: it’s based on the same source as the Blood Rage version, but trims the violence as per the original Nightmare at Shadow Woods edit and restores the footage exclusive to that edit of the picture from a 35mm print source. Consequently, there’s a notable difference in quality between that footage and the surrounding source, with the inserts from the Nightmare at Shadow Woods edit (ie, the poolside sequence) displaying noticeable print damage and more striking contrast. The third edit of the film that’s included in this release is a composite of both cuts of the film, which retains the violence of the Blood Rage edit and also incorporates the narrative footage exclusive to the Nightmare at Shadow Woods cut.  On disc one, Blood Rage runs for 82:13 mins; on disc two, Nightmare at Shadow Woods runs for 79:26 mins, and the composite edit runs for 85:07 mins. On disc one, Blood Rage runs for 82:13 mins; on disc two, Nightmare at Shadow Woods runs for 79:26 mins, and the composite edit runs for 85:07 mins.

Presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio (and using the AVC codec), the presentation of the main feature is very good. A strong level of detail is present throughout, and it’s a remarkably ‘clean’ presentation, free of damage and debris. (There are a handful of shots, such as Maddy seated by the fridge and devouring its contents, which seem to have been photographed with a wide open aperture and shallow depth of field but are clumsily out of focus – presumably a product of a rushed shooting schedule.) Contrast levels are nicely-balanced, with the night-time sequences (making up the bulk of the film) evidencing this the most strongly: within the film’s mise-en-scène, there’s a juxtaposition of the brightly-lit interiors used towards the beginning of the picture (eg, Maddy’s house, with its tacky pink/beige/cream décor) and the dark night-time exteriors. Towards the climax, the film moves back indoors, into increasingly dark interiors, with a number of scenes towards the climax taking place in Shadow Woods’ indoor swimming pool, where reflections of light from the water of the pool give the scenes an almost chiaroscuro appearance. This contrast between areas (and scenes) of light and darkness is handled very well within this presentation. Finally, a characteristically strong encode ensures that the picture’s organic grain structure is intact, giving the presentation a pleasingly film-like appearance. NB. Some large screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. There’s a little background hiss present which is noticeable in some scenes more than others. The track demonstrates good range, as evidenced in the bassy disco-style opening titles music. It’s not a ‘showy’ track by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s presented nicely on this disc. The film is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

DISC ONE:  * The film (Blood Rage edit) (82:13) * The film (Blood Rage edit) (82:13)

- Audio commentary with director John Grissmer, moderated by Ewan Cant. This is an interesting commentary in which Grissmer recalls the production, offering some fascinating anecdotes about the production and the film’s eventual release. - ‘Double Jeopardy’ (11:01). Here, Mark Soper talks about his dual role as Terry and Todd. Soper talks about his acting idols (Brando, Clift, Dean, DeNiro, Pacino). Soper says that the slasher film is often about ‘the bad guy that looks good and the good guy that looks guilty’, and suggests that this was his approach to playing Terry and Todd. What Soper likes about ‘these kinds of movies’ is the ability to ‘take some chances’ which ‘sometimes they pan out and sometimes they don’t’. The film’s many titles caused problems for Soper when he put the picture on his resume. Soper also talks about his reaction to the knowledge that the picture has developed a cult following, and he says that ‘it has to have something organic that it is touching some need in people that they want to come back to it’. - ‘Jeez, Louise!’ (10:21). Louise Lasser reflects on her acting career and says she ‘had a natural propensity at acting’: she never studied the art formally, feeling that instead you could ‘just do it’. ‘People think you pick and plan these things, and you don’t’, Lasser argues when reflecting on Blood Rage specifically: independent films are ‘so much work over such a short time’. Lasser reveals that she struggled to tell the characters of Todd and Terry apart, but argues that as the character suffered from the same confusion, this was ‘okay’. - ‘Both Sides of the Camera’ (9:38). This is an interview with Marianne Kanter, who both produced the film and acted in it (in the role of Dr Berman). Kanter talks about the process of producing a film, and reveals that she wasn’t originally intended to act in the film but stood in for a New York actress who let the production down at the last minute. She talks about the difficulties faced by a female producer, at a time when it was rare for women to take such a role in the filmmaking process. Kanter discusses the difficulties faced during the production and praises Ed French’s effects work on the picture. She also talks about the problems in finding distribution for the film, owing to its emphasis on gore effects.  - ‘Man Behind the Mayhem’ (12:48). In this interview, Ed French, who created the film’s effects, talks about his work on the picture. French discusses his early career as an actor and how he became involved in special effects work. He was approached by Marianne Kanter to work on Blood Rage and saw the opportunity to work on a ‘super gory slasher movie’, a film that ‘had a real operatic sensibility, that was way over the top and extreme’. French says that he wanted to use the actors in the effects shot as much as possible, avoiding the use of dummies and such owing to the inauthentic characteristics of dummy shots. French talks about using one of the apartments at the shooting location as his makeup lab, and he also discusses some of the specific makeup effects used within the picture. French also talks about his movement away from independent productions to work on Hollywood features like Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Nicholas Meyer, 1991) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991). - ‘Man Behind the Mayhem’ (12:48). In this interview, Ed French, who created the film’s effects, talks about his work on the picture. French discusses his early career as an actor and how he became involved in special effects work. He was approached by Marianne Kanter to work on Blood Rage and saw the opportunity to work on a ‘super gory slasher movie’, a film that ‘had a real operatic sensibility, that was way over the top and extreme’. French says that he wanted to use the actors in the effects shot as much as possible, avoiding the use of dummies and such owing to the inauthentic characteristics of dummy shots. French talks about using one of the apartments at the shooting location as his makeup lab, and he also discusses some of the specific makeup effects used within the picture. French also talks about his movement away from independent productions to work on Hollywood features like Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Nicholas Meyer, 1991) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991).

- ‘Three Minutes with Ted’ (3:18). This short interview with Ted Raimi features Raimi discussing his association with the picture, and his small role within it. Raimi was involved in a car accident with a policecar and was prohibited from driving a car and also had a large fine to pay. Raimi moved to New York, and his father told him that he had to find an acting job within a year or else he would have to work in his father’s business. Luckily, Raimi managed to snag the small role he plays in this film, which was his first acting part. - ‘Return to Shadow Woods’ (5:36). This featurette sees Ed Tucker, a film historian from Jacksonville, where Blood Rage was shot, visiting some of the locations used during the shooting of the picture. - VHS Opening Titles (5:00). These are the opening titles from the VHS release of the picture. - Behind-the-Scenes Gallery (4:31). This is a series of images shot during the film’s production. DISC TWO: * The film: - Nightmare at Shadow Woods cut (79:26). - Composite edit (85:07). - Outtakes (26:39). These are raw outtakes from the production. Retail copies also include reversible sleeve artwork and one of Arrow’s characteristically lush booklets, illustrated with stills from the film, which contains information about the restoration and a new piece about the film by Joseph Ziemba of Bleeding Skull! video and the co-author of the books Bleeding Skull! and DESTROY ALL MOVIES!!!

Overall

Blood Rage is a hugely entertaining picture that veers between offering a deadly serious (pun intended) approach to its subject matter and treading into the realm of self-parody. There’s some wildly outlandish intentional humour within the picture that complements, rather than contradicts, the bizarrely excessive scenes of murder and mayhem. Karen perhaps offers the defining statement within the film when, after Terry has killed a number of her friends in the most spectacularly brutal manner, she declares in a deadpan fashion, ‘This thing has got totally out of hand’. Watching the film, the viewer might well find themselves agreeing with Karen – though the absurd excessiveness of the picture makes it a delight to watch. Blood Rage is a hugely entertaining picture that veers between offering a deadly serious (pun intended) approach to its subject matter and treading into the realm of self-parody. There’s some wildly outlandish intentional humour within the picture that complements, rather than contradicts, the bizarrely excessive scenes of murder and mayhem. Karen perhaps offers the defining statement within the film when, after Terry has killed a number of her friends in the most spectacularly brutal manner, she declares in a deadpan fashion, ‘This thing has got totally out of hand’. Watching the film, the viewer might well find themselves agreeing with Karen – though the absurd excessiveness of the picture makes it a delight to watch.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Blood Rage is a superb package, containing three edits of the picture and some great contextual material in the form of a commentary track with Grissmer and a number of illuminating interviews. Fans of American bodycount/slasher films will find this release to be an absolute delight. References: Cettl, Robert, 2013: Offensive to a Reasonable Adult: Film Censorship and Classification in Australia. Adelaide: Robert Cettl E-Books

|

|||||

|