|

The Film

Cherry 2000 (Steve De Jarnatt, 1987) Cherry 2000 (Steve De Jarnatt, 1987)

Written by off-beat ‘indie’ director Michael Almereyda a year before his debut feature Twister (1988) – though Almereyda had already directed a well-received short film, ‘A Hero of Our Time’ (1985), inspired by a chapter in Mikhail Lermentov’s 1838 novel of the same title – Cherry 2000 (1987) was directed by Steve De Jarnatt, who was, in his own words, ‘a late fill-in for a director who’d left the project’ (De Jarnatt, quoted in Chaw, 2012: 177). De Jarnatt confessed that he ‘just sort of did’ Cherry 2000, reflecting that he shot the script ‘letter-for-letter’ and that the production was fraught with conflict: ‘we get to the shoot and we realize that there’s no money, none of the sets have been built, the cast and crew were constantly squabbling… It was not a pleasant experience’ (De Jarnatt, quoted in ibid.: 176).

The film begins with a domestic scene so idyllic that it edges into parody. Sam Treadwell (David Andrews) arrives home to find that his partner Cherry (Pamela Gidley) greets him warmly. However, Cherry is a robot – a highly sought-after Cherry 2000 model. When Cherry malfunctions, Sam enlists the help of a ‘tracker’, E Johnson (Melanie Griffith), who offers to take Sam into Zone 7 – in reality, Las Vegas, which has been swallowed up by sand – in order to acquire a rare Cherry 2000 chassis into which Sam can place the personality chip from his own Cherry 2000. Sam and Johnson are aided by Johnson’s mentor Six Fingered Jake (Ben Johnson), but they come into conflict with Lester (Tim Thomerson), who with his gang of hoodlums controls Zone 7.

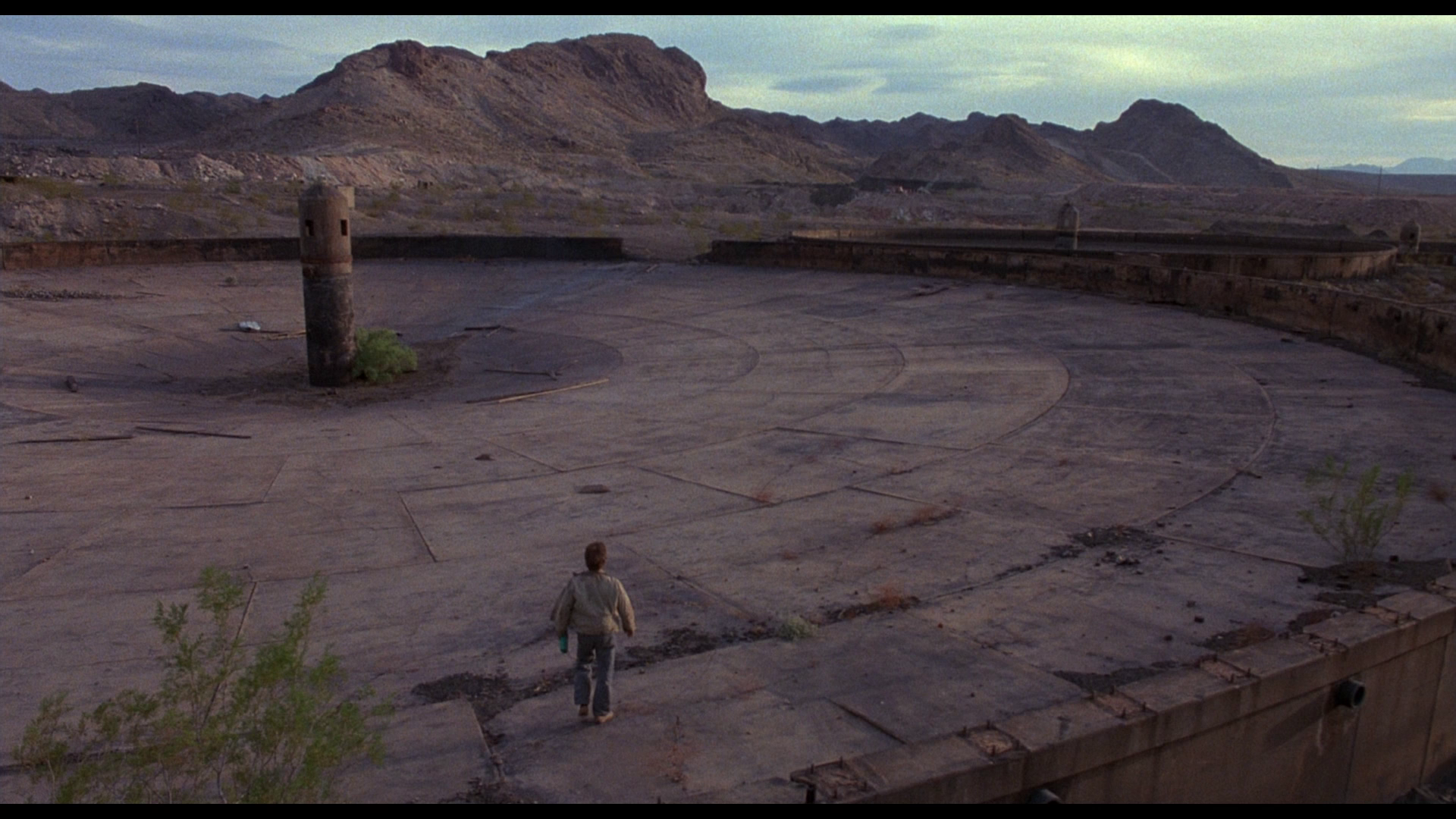

The film is named after Cherry 2000, the specific model of pleasure droid whose loss Sam mourns and which has since been replaced by more sophisticated, but less sought after, models. Sam’s quest to find a Cherry 2000 body in which to put the chip of his own droid leads to the ruined Las Vegas, its streets covered over with sand so that only the tips of its casinos are visible. It’s one of these casinos, Pharaohs, that Sam and Johnson enter in order to retrieve the ultra-rare Cherry 2000 body; there’s a suggestion that the Cherry 2000 models were pleasure droids ‘employed’ in the casinos.

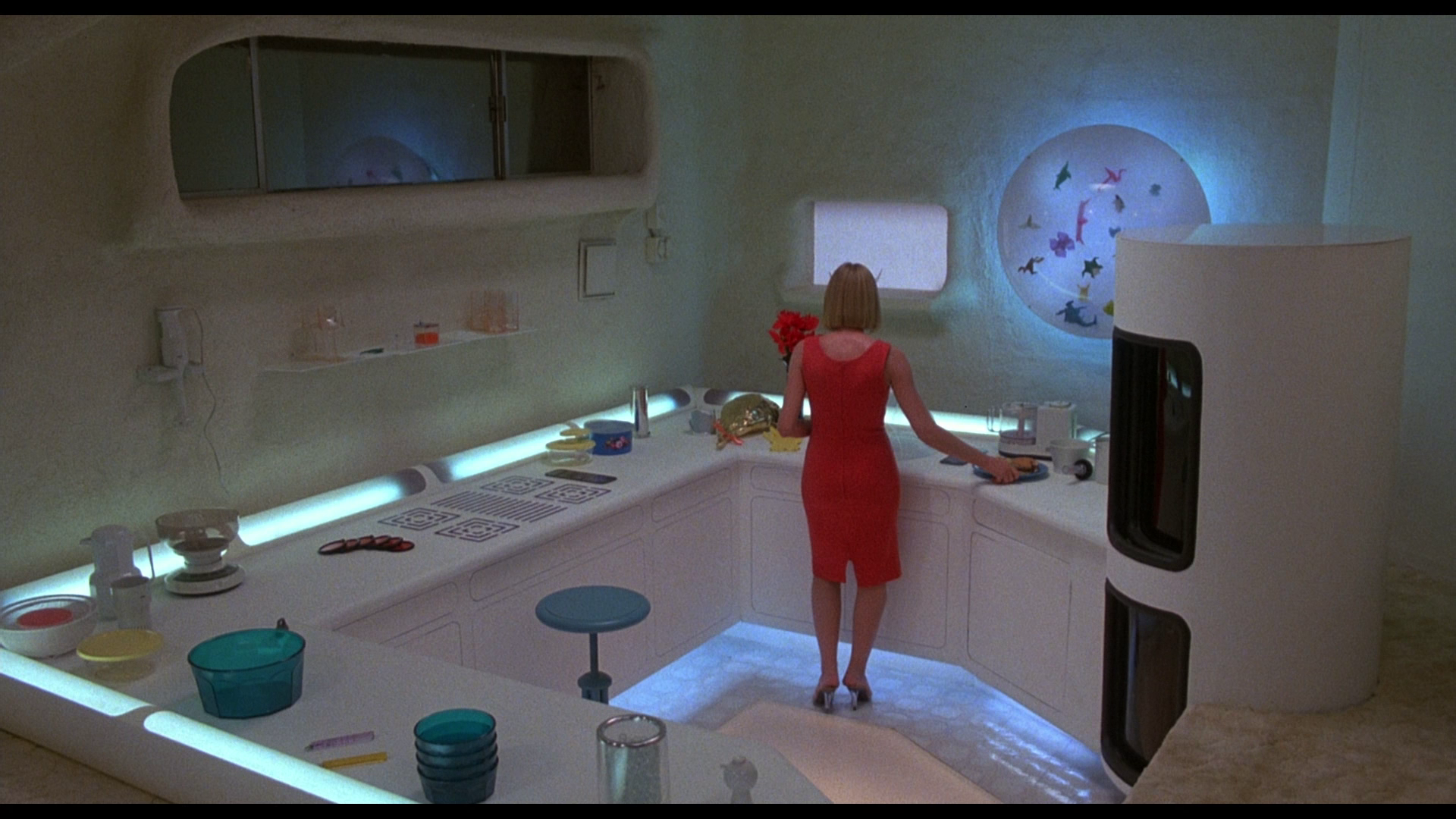

In the opening sequence, the audience is given the clue that something is ‘off’ about Cherry by her overly subservient behaviour: she beavers away prior to Sam’s return home, waiting for the return of the head of the househole like a parody of a 1950s housewife. The preponderance of red within the mise-en-scène (Cherry’s red dress; the red candlesticks) might suggest to the audience passion or perhaps danger. Sam sits down to eat the food that Cherry has prepared for him; they converse, and Cherry tells Sam about tidbits of information she has picked up from the television. Sam mocks Cherry slightly, and she looks confused and hurt; this moment punctures the idealised construction of this patriarchal scenario. In the kitchen, Sam and Cherry kiss passionately on the floor as the sink overflows with soap suds. The soap suds spill out onto the floor, and Sam and Cherry roll amidst them, locked in an embrace. However, Cherry short-circuits in the water; it’s then that we realise she is a robot, providing a context for her subservient prior behaviour. In the opening sequence, the audience is given the clue that something is ‘off’ about Cherry by her overly subservient behaviour: she beavers away prior to Sam’s return home, waiting for the return of the head of the househole like a parody of a 1950s housewife. The preponderance of red within the mise-en-scène (Cherry’s red dress; the red candlesticks) might suggest to the audience passion or perhaps danger. Sam sits down to eat the food that Cherry has prepared for him; they converse, and Cherry tells Sam about tidbits of information she has picked up from the television. Sam mocks Cherry slightly, and she looks confused and hurt; this moment punctures the idealised construction of this patriarchal scenario. In the kitchen, Sam and Cherry kiss passionately on the floor as the sink overflows with soap suds. The soap suds spill out onto the floor, and Sam and Cherry roll amidst them, locked in an embrace. However, Cherry short-circuits in the water; it’s then that we realise she is a robot, providing a context for her subservient prior behaviour.

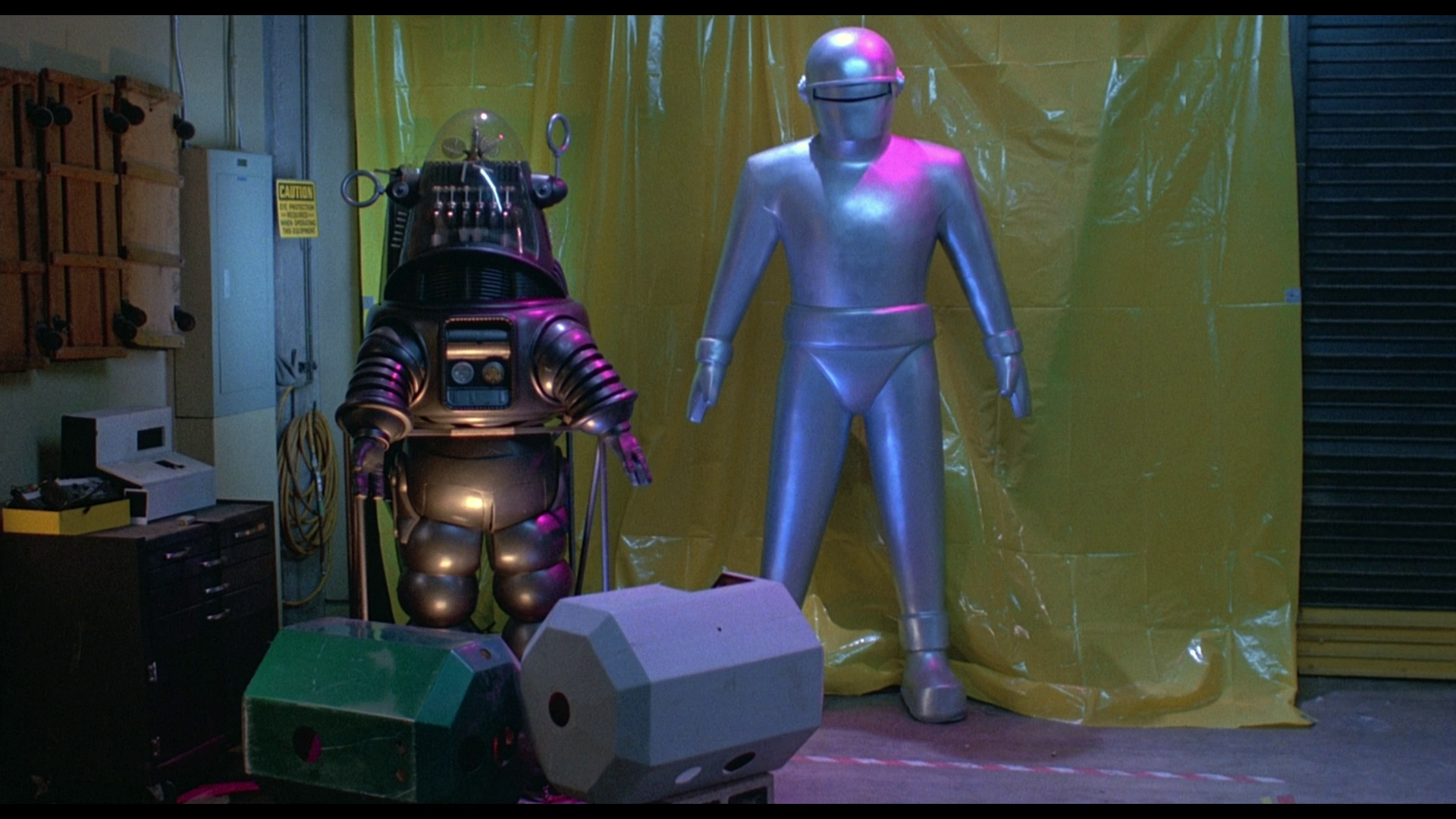

The film equates femininity with commodification: in the world depicted within Cherry 2000, desire is a commodity that can be bought and sold. Sam’s mechanic Slim (Michael C Gwynne) informs Sam that Cherry has undergone a ‘Total internal meltdown’ and highlights the desirability of the Cherry 2000 model: it’s an old model, a ‘thing of the past’, and ‘They don’t get any finer than this’. Sam grumbles about the impossibility of repairing Cherry, and Slim expresses his sympathies: ‘I know how it is’, Slim says, ‘You’re like me: a romantic. Most of these birds, they come in here, they don’t care. It’s all apple pan dowdy to them. But you and I both know, each one of these honeys is special. Got her own special magic, her own special way. Isn’t that true?’ In Slim’s workshop are other robots, some of them later, inferior models; some of these are designed for sexual exploitation, others are not. Amidst them are replicas of Robbie the Robot, from Lost in Space, and Gort, from The Day the Earth Stood Still – indices of the utilitarian, sexless robots of past science-fiction. (Later, to Sam’s visible disgust, Lester comments in relation to the Cherry 2000 model, ‘You get one of these fired up, it’s like slamming an octopus’.) ‘What am I gonna do, Slim?’, Sam laments, ‘It’s Cherry or nothin’!’ Sam is so taken with his Cherry 2000 that, prior to seeking out and hiring Johnson, he lays in bed with the ‘corpse’ of his droid next to him.

The film contains a bizarrely-realised future world – one in which literally everything is recyclable, recycled at enormous plants (Sam is an employee of one of these plants) in which those bringing items to be recycled are moved around on huge elevators and moving walkways. The film contains a bizarrely-realised future world – one in which literally everything is recyclable, recycled at enormous plants (Sam is an employee of one of these plants) in which those bringing items to be recycled are moved around on huge elevators and moving walkways.

Within this context, the film’s use of – seemingly exclusively female – robots suggests a commodification of the self; a confusion of the human with the inhuman. Sam’s Cherry 2000 cannot be recycled: Sam will accept no substitutes. Much like many other films featuring robots and synthetic humans, the film depicts the Cartesian split between the ‘mind’ and the ‘body’ by suggesting that Cherry’s self – her personality and identity – is contained on the microchip which can be removed from her body and placed into an identical model. Sam carries the personality chip of his Cherry with him on his adventure, playing back their conversations in a romantic daydream (much to the amusement of Johnson).

Within the world of Cherry 2000, human relationships have become so complicated that using a droid for acts of sexual recreation seems the most logical, and least traumatic, option. When his workmates discover that Sam’s Cherry 2000 has malfunctioned, they offer to take him to Glu Glu Club, where there are ‘real women’ (in the words of Sam’s friends). There, one of the first phrases we hear is spoken by a woman: ‘Want some? Let’s get it down on paper’. Dating couples are accompanied by lawyers who negotiate contracts between the respective parties for sexual intercourse (one of these lawyers is played by Larry Fishburne): ‘A standard one night encounter, right?’, a lawyer asks his client at one of the tables in the club, ‘So, well say a dinner, complete sexual encounter, full penetration, optional episode in the morning, right?’ As Dominic Pettman notes, within the film ‘Twenty-first-century urban mating-rituals are portrayed as highly mediated: every sexual encounter between actual humans is computer-simulated beforehand, and then agreed to on a contractual basis’ (Pettman, 2002: 89). The ‘first casualty of this artificial, alienating, and legally binding system’ is spontaneity, and ‘[r]eal women are represented as alternatively confrontational, shrill, or demanding’ and this is why Sam ‘believes in the relative authenticity, not to mention the 1950s’ compliance, of his Cherry 2000’ (ibid.).

Sam visits a rough part of town to hire the tracker Johnson, recommended to him by Slim, and is surprised when he discovers that Johnson is in fact a woman. For her part, Johnson tells Sam that ‘This isn’t a dating service’ and that Sam will need to go along with her, to ‘ride shotgun’ so that Johnson may ‘make it out [of Zone 7] in one piece’. Sam reacts negatively to this, and visits a bar – which is more like a saloon from a Western – where he meets another tracker, Stacey (Brion James). Sam outlines his problem to Stacey, who asks, ‘My, my, is that a Cherry?’ ‘Cherry 2000’, Sam corrects him. ‘Va-voom’, Stacey observes. However, Stacey leads Sam outside where he and his associate Earl (Claude Earl Jones) hold Sam at gunpoint, hoping to take from him his highly desirable Cherry 2000 personality chip. However, Sam manages to escape, fleeing back to Johnson and hiring her. Sam visits a rough part of town to hire the tracker Johnson, recommended to him by Slim, and is surprised when he discovers that Johnson is in fact a woman. For her part, Johnson tells Sam that ‘This isn’t a dating service’ and that Sam will need to go along with her, to ‘ride shotgun’ so that Johnson may ‘make it out [of Zone 7] in one piece’. Sam reacts negatively to this, and visits a bar – which is more like a saloon from a Western – where he meets another tracker, Stacey (Brion James). Sam outlines his problem to Stacey, who asks, ‘My, my, is that a Cherry?’ ‘Cherry 2000’, Sam corrects him. ‘Va-voom’, Stacey observes. However, Stacey leads Sam outside where he and his associate Earl (Claude Earl Jones) hold Sam at gunpoint, hoping to take from him his highly desirable Cherry 2000 personality chip. However, Sam manages to escape, fleeing back to Johnson and hiring her.

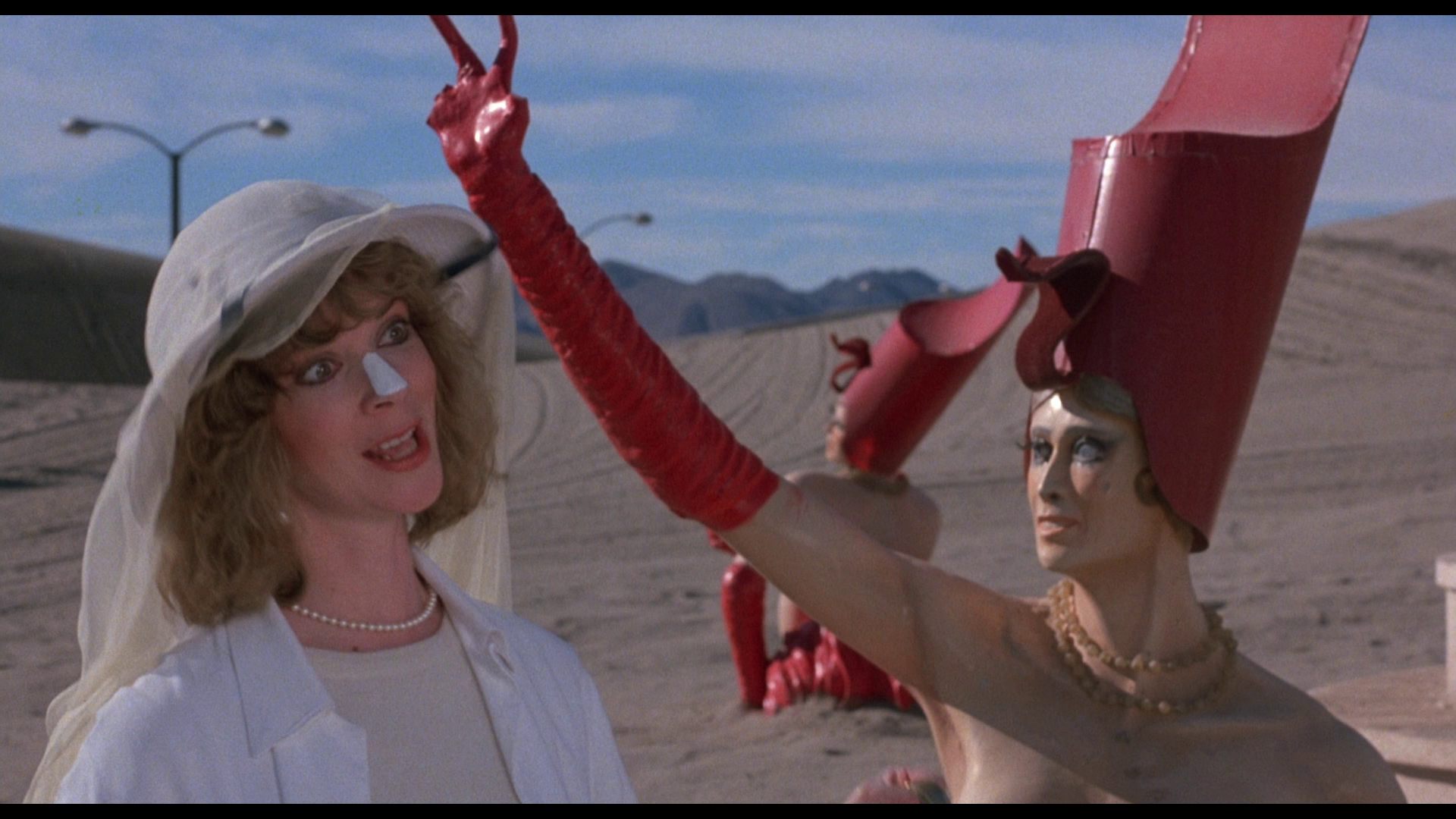

Sam and Johnson’s journey into Zone 7 begins with Johnson driving her car through a barricade populated by outlaws who shoot at the vehicle. ‘Just keep your head down low and try not to get shot’, Johnson advises Sam before telling him those manning the barricade are ‘a bunch of freaks out on the edges. They got nothing to do; they’re bored. They just want a little action. It’s real immature’. Zone 7 itself is a post-apocalyptic wasteland. Taking a break on the edge of a huge quarry, Johnson and Sam watch as, on the other side of the quarry, Lester and his gang attack a man who has ventured into Zone 7, pushing the man’s vehicle into the quarry itself. Lester is, in the words of Johnson, ‘A total whacko’.

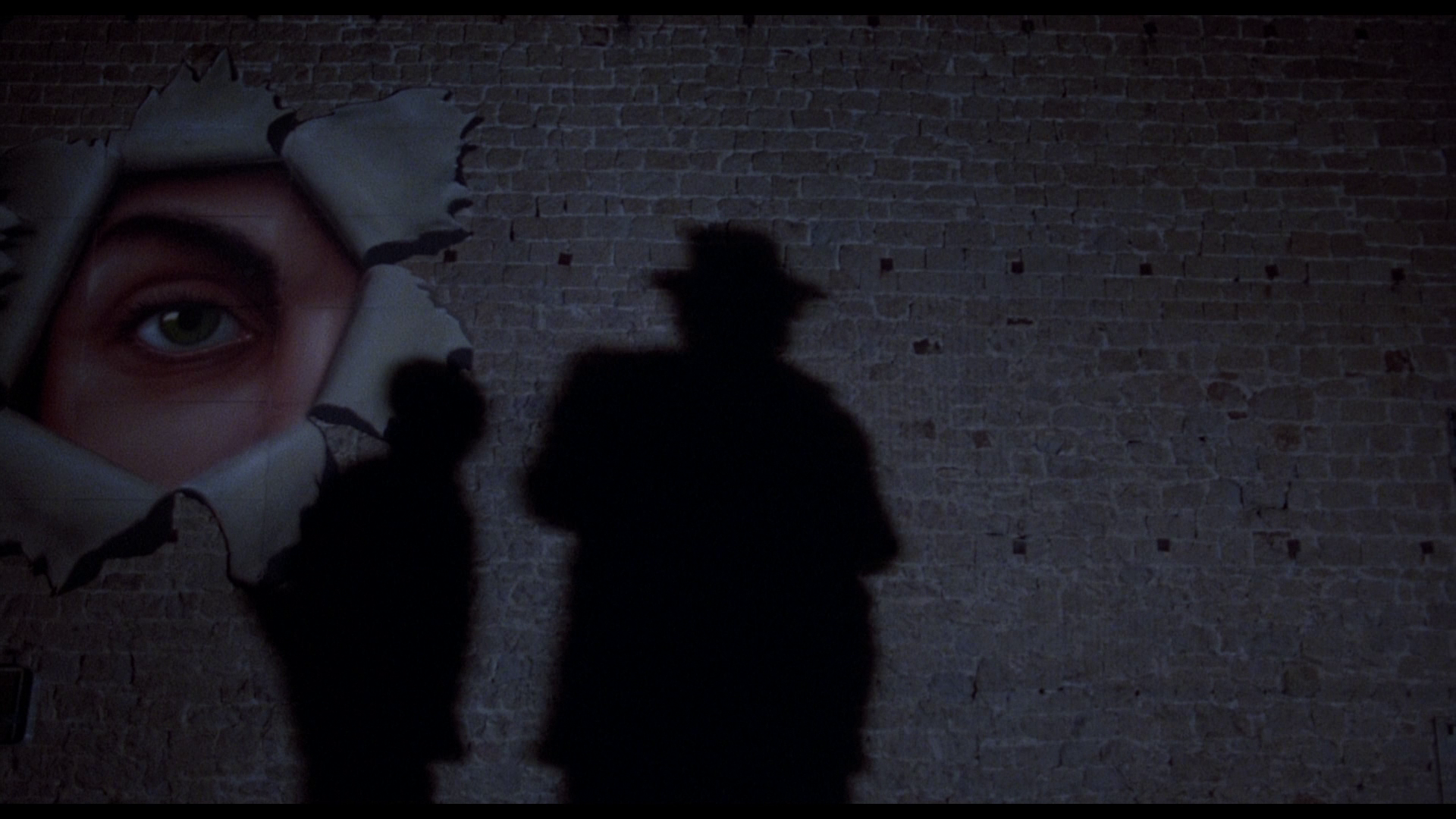

Later in the film, Sam is captured by Lester and his gang, passing out and then waking up in a strange poolside retreat (Sky Ranch) where he is greeted by his old girlfriend Elaine (Cameron Milzer). Elaine, who now goes by the name of ‘Ginger’, is apparently Lester’s moll. For his part, Lester greets Sam warmly: ‘How’s it going, Sam?’, Lester asks, shaking Sam’s hand: ‘Good to see you on your feet’. Lester’s gang has its own society; the members dress in leisurewear (shorts, Hawaiian shirts) but carry automatic weapons. ‘We got a programme here’, Lester tells Sam, ‘Diet, exercise, mental discipline. I like to see people reach their full potential’. During an evening celebration, Sam watches as Lester brutally executes a tracker; meanwhile, Elaine tells Sam, ‘I think you should just stick around, give this place a chance’. However, Sam flees from the camp and regroups with Johnson, and taking a biplane from some of Lester’s associates the couple fly out to Vegas. There, they wander amidst the ruins of the city, now buried under sand so that only the tips of the casinos are visible; climbing through the roof of one particular casino (Pharaohs), they descend into its belly to discover a room filled with pleasure droids (including Cherry 2000 models) which, wrapped in plastic, are hanging from the ceiling like animal carcasses in a slaughterhouse. However, Sam begins to realise the value of a human woman (Johnson) over the company of a robot (Cherry 2000). At the end of the film, Sam ditches Cherry from his plane so that he can save Johnson from Lester’s gang. ‘What about her?’, Johnson asks Sam, ‘She was the whole point’. ‘She’s a robot’, Sam tells her, before the couple kiss.

Martin Winkler has suggested that Sam’s journey into Zone 7 with Johnson to ‘rescue’ a Cherry 2000 model is a katabatic journey that may be compared with Orpheus’ descent into the underworld to return Eurydice to the land of the living (Winkler, 2001: 18). Sam and Johnson’s journey to Zone 7 is, Winkler argues, ‘replete with and remarkably faithful to the ancestral themes we have come to expect for this part of the descent tale’, including the pair travelling ‘mainly at night, avoiding the various marauding outlaw bands that dot the barren landscape’ (ibid.). Part of their journey involves being dropped down the large drainage shaft of what appears to be the ruins of a hydroelectric dam, at the bottom of which they are met by a man on a raft with two burros aboard. The man is Six Fingered Jake, Johnson’s mentor, who is presumed by many of the characters to be dead. (This is the cue for a number of jokes which allude to the frequent refrain in George Sherman’s 1971 Big Jake, and of course John Carpenter’s 1982 Escape from New York: ‘I heard you were dead’. ‘“Retired”, more like’, is Six Fingered Jake’s response to this question, ‘I been trying to create a more “serene” outlook’.) Like Charon, Jake – a man returned from the dead – carries Sam and Johnson across the river. When Sam and Johnson descend into the Las Vegas casino and encounter the various sex bots hanging from hooks along the ceiling, their bodies sealed in plastic bags, ‘[w]e can’t help but think of Anticleia’s description of the spirits to her son Odysseus: “The flesh and bones are no longer possessed of strength, but the powerful might of blazing fire overpowers them as soon as the personality has abandoned the white bones. And the spirit goes flying, flitting off like a dream”’ (Homer, quoted in ibid.). Martin Winkler has suggested that Sam’s journey into Zone 7 with Johnson to ‘rescue’ a Cherry 2000 model is a katabatic journey that may be compared with Orpheus’ descent into the underworld to return Eurydice to the land of the living (Winkler, 2001: 18). Sam and Johnson’s journey to Zone 7 is, Winkler argues, ‘replete with and remarkably faithful to the ancestral themes we have come to expect for this part of the descent tale’, including the pair travelling ‘mainly at night, avoiding the various marauding outlaw bands that dot the barren landscape’ (ibid.). Part of their journey involves being dropped down the large drainage shaft of what appears to be the ruins of a hydroelectric dam, at the bottom of which they are met by a man on a raft with two burros aboard. The man is Six Fingered Jake, Johnson’s mentor, who is presumed by many of the characters to be dead. (This is the cue for a number of jokes which allude to the frequent refrain in George Sherman’s 1971 Big Jake, and of course John Carpenter’s 1982 Escape from New York: ‘I heard you were dead’. ‘“Retired”, more like’, is Six Fingered Jake’s response to this question, ‘I been trying to create a more “serene” outlook’.) Like Charon, Jake – a man returned from the dead – carries Sam and Johnson across the river. When Sam and Johnson descend into the Las Vegas casino and encounter the various sex bots hanging from hooks along the ceiling, their bodies sealed in plastic bags, ‘[w]e can’t help but think of Anticleia’s description of the spirits to her son Odysseus: “The flesh and bones are no longer possessed of strength, but the powerful might of blazing fire overpowers them as soon as the personality has abandoned the white bones. And the spirit goes flying, flitting off like a dream”’ (Homer, quoted in ibid.).

Meanwhile, Paula James has suggested that Cherry 2000 has a number of similarities with the myth of Pygmalion, with echoes of Ira Levin’s 1972 novel The Stepford Wives (James, 2011: 134). In the myth of Pygmalion, of course, Pygmalion’s impossible love for Aphrodite, the goddess, is not reciprocated, and so Pygmalion recreates Aphrodite, building her likeness in ivory. He prays for his creation to be given life, and Aphrodite concedes; the artificial woman is (re)born as Galatea, an image of the ‘perfect’ woman. As James notes, Cherry is ‘a facsimile of an ideal wife’ who is ‘designed to display a happy fulfilment in satisfying her man’s every need’ (ibid.). She exhibits ‘a limited capacity for absorbing “interesting facts” from the television but intellectual engagement is beyond her programming’ (ibid.). As the film begins, Sam returns home to Cherry; she greets him happily and has prepared his meal: ‘a twentieth-century soap opera appears to be underway’ (ibid.). However, something is ‘off’ about Cherry’s too-happy demeanour; there’s a slight disconnect in their conversation. After Cherry is destroyed, Sam goes on a quest to find another Cherry 2000 body in which to put the personality chip of his own robot, and the film is about his ‘transformation […] into a less superficial human being’ who, at the end of the picture, chooses to sacrifice ‘his retrieved robot wife to rescue his real girl companion’ – even though the latter, ‘roughly hewn, morose and fierce’, contrasts sharply with the ‘helpless and chirpy Cherry’ (ibid.). James suggests that ‘[t]his is corny stuff and the message is hardly profound’; however, the film nevertheless ‘show[s] a Pygmalion figure revived and redeemed, realizing that a life of unalloyed pleasure with a passive partner is far less interesting than trouble-shooting with Johnson’ (ibid.). Meanwhile, Paula James has suggested that Cherry 2000 has a number of similarities with the myth of Pygmalion, with echoes of Ira Levin’s 1972 novel The Stepford Wives (James, 2011: 134). In the myth of Pygmalion, of course, Pygmalion’s impossible love for Aphrodite, the goddess, is not reciprocated, and so Pygmalion recreates Aphrodite, building her likeness in ivory. He prays for his creation to be given life, and Aphrodite concedes; the artificial woman is (re)born as Galatea, an image of the ‘perfect’ woman. As James notes, Cherry is ‘a facsimile of an ideal wife’ who is ‘designed to display a happy fulfilment in satisfying her man’s every need’ (ibid.). She exhibits ‘a limited capacity for absorbing “interesting facts” from the television but intellectual engagement is beyond her programming’ (ibid.). As the film begins, Sam returns home to Cherry; she greets him happily and has prepared his meal: ‘a twentieth-century soap opera appears to be underway’ (ibid.). However, something is ‘off’ about Cherry’s too-happy demeanour; there’s a slight disconnect in their conversation. After Cherry is destroyed, Sam goes on a quest to find another Cherry 2000 body in which to put the personality chip of his own robot, and the film is about his ‘transformation […] into a less superficial human being’ who, at the end of the picture, chooses to sacrifice ‘his retrieved robot wife to rescue his real girl companion’ – even though the latter, ‘roughly hewn, morose and fierce’, contrasts sharply with the ‘helpless and chirpy Cherry’ (ibid.). James suggests that ‘[t]his is corny stuff and the message is hardly profound’; however, the film nevertheless ‘show[s] a Pygmalion figure revived and redeemed, realizing that a life of unalloyed pleasure with a passive partner is far less interesting than trouble-shooting with Johnson’ (ibid.).

The film is uncut and runs for 98:31 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on its disc, this presentation of Cherry 2000 is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Lots of detail is present within the image, and the colours have a vivid quality that the film’s previous home video incarnations never had. This can be seen in the red of Cherry’s dress at the start of the film, and the red/pink background against which Cherry’s silhouette is photographed in the film’s opening titles. Contrast levels are nicely-balanced, with detail present in low-light shots. Some shots exhibit a little damage here and there, but nothing too distracting. Finally, a strong encode, using the AVC codec, ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on its disc, this presentation of Cherry 2000 is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Lots of detail is present within the image, and the colours have a vivid quality that the film’s previous home video incarnations never had. This can be seen in the red of Cherry’s dress at the start of the film, and the red/pink background against which Cherry’s silhouette is photographed in the film’s opening titles. Contrast levels are nicely-balanced, with detail present in low-light shots. Some shots exhibit a little damage here and there, but nothing too distracting. Finally, a strong encode, using the AVC codec, ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented by a LPCM 2.0 track, accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The LPCM track is rich and resonant, with punchy bass (eg, in the pops and bangs as Cherry short-circuits during the opening sequence). The track has strong range: Johnson’s care engine sounds like an aeroplane taking off in your living room. Basil Poledouris’ superb score, which has echoes of his music for Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (released the same year, in 1987) is showcased nicely on this track too.

Extras

The disc includes a commentary with director Steve De Jarnatt. De Jarnatt discusses the production of the film and also reflects on some of its themes. The track has some periods of silence, but this is mitigated by the quality of the comments and reflections from De Jarnatt. The disc includes a commentary with director Steve De Jarnatt. De Jarnatt discusses the production of the film and also reflects on some of its themes. The track has some periods of silence, but this is mitigated by the quality of the comments and reflections from De Jarnatt.

Also included are:

- an interview with Tim Thomerson (13:04). Thomerson talks about how he came to be involved in the film and discusses the shooting of the picture. Perhaps surprisingly, given his roles in pictures such as this and the Trancers films, Thomerson suggests a dislike of science fiction cinema generally.

- ‘Making Cherry 2000’ (6:23). This vintage featurette about the production of the film includes some behind the scenes footage, interviews and clips from the completed picture.

Finally, the disc includes the film’s trailer (2:25) – a strange one which features Bernard Herrmann’s score for Taxi Driver(!) – and a stills gallery (0:23).

Overall

Cherry 2000 is a fun film – much more fun than I remembered it to be. The film’s futuristic setting (in 2017 – not too far away now), its focus on sexuality and its bizarre shifts in tone are perhaps most reminiscent of LQ Jones’ 1975 film adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s A Boy and His Dog. (Oddly, the picture feels very contemporary in light of Bethesda’s recent videogame Fallout 4, which has a similar atmosphere.) Almereyda’s script, like much of his work, has echoes of classical mythology and literature – specifically, here, the myths of Pygmalion and Orpheus. The film itself is very nicely-photographed, though its jarring tonal shifts may alienate some viewers. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is very good indeed, and the disc contains some strong contextual material too. Fans of 1980s science fiction pictures will find much to enjoy here. Cherry 2000 is a fun film – much more fun than I remembered it to be. The film’s futuristic setting (in 2017 – not too far away now), its focus on sexuality and its bizarre shifts in tone are perhaps most reminiscent of LQ Jones’ 1975 film adaptation of Harlan Ellison’s A Boy and His Dog. (Oddly, the picture feels very contemporary in light of Bethesda’s recent videogame Fallout 4, which has a similar atmosphere.) Almereyda’s script, like much of his work, has echoes of classical mythology and literature – specifically, here, the myths of Pygmalion and Orpheus. The film itself is very nicely-photographed, though its jarring tonal shifts may alienate some viewers. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is very good indeed, and the disc contains some strong contextual material too. Fans of 1980s science fiction pictures will find much to enjoy here.

References:

Chaw, Walter, 2012: Miracle Mile. Lulu.com

James, Paula, 2011: Ovid’s Myth of Pygmalion on Screen: In Pursuit of the Perfect Woman. London: Continuum

Pettman, Dominic, 2002: After the Orgy: Toward a Politics of Exhaustion. State University of New York

Winkler, Martin M, 2001: ‘Introduction’. In: Winkler, Martin M (ed), 2001: Classical Myth and Culture in the Cinema. Oxford University Press: 3-22

|