|

|

Gas-s-s-s AKA Gas! AKA Gas! Or: It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th January 2016). |

|

The Film

Gas-s-s-s; Or: It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It (Roger Corman, 1970) Gas-s-s-s; Or: It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It (Roger Corman, 1970)

In the mid-1960s, tired of the studiobound nature and period setting of the Edgar Allan Poe adaptations for which he was most famous, Roger Corman decided to make a series of pictures that were contemporary in their setting and theme, and shot largely on location. The first of these was his biker film The Wild Angels (1966); the second was the LSD picture The Trip (1967, recently released on Blu-ray by Signal One and reviewed by us here). These two films – especially the latter, which brought together Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Jack Nicholson – led indirectly to the production of what is arguably the defining counterculture picture of the late-1960s, Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), which was originally intended to be produced by Corman before the project was passed on to Columbia Pictures. Meanwhile, in the year of Easy Rider’s release, Corman made his own counterculture film Gas-s-s-s; Or: It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It (1970). AIP’s handling of Gas-s-s-s led to Corman leaving the company in 1969, prior to the film’s release, forming New World Pictures.  Following the accidental release of a gas which causes the accelerated breakdown of neurons in anyone over the age of twenty-five, the world is left in the hands of young people. Amidst this, in Dallas young couple Coel (Robert Corff) and Cilla (Elaine Giftos) decide to flee the city. They encounter another group of survivors in a record shop: former Black Panther Carlos (Ben Vereen), his lover Marissa (Cindy Williams), Hooper (Bud Cort) and Coralee (Talia Shire). They tell Coel and Cilla that they are heading to a new utopian society in New Mexico. Coel and Cilla decide to join them. Following the accidental release of a gas which causes the accelerated breakdown of neurons in anyone over the age of twenty-five, the world is left in the hands of young people. Amidst this, in Dallas young couple Coel (Robert Corff) and Cilla (Elaine Giftos) decide to flee the city. They encounter another group of survivors in a record shop: former Black Panther Carlos (Ben Vereen), his lover Marissa (Cindy Williams), Hooper (Bud Cort) and Coralee (Talia Shire). They tell Coel and Cilla that they are heading to a new utopian society in New Mexico. Coel and Cilla decide to join them.

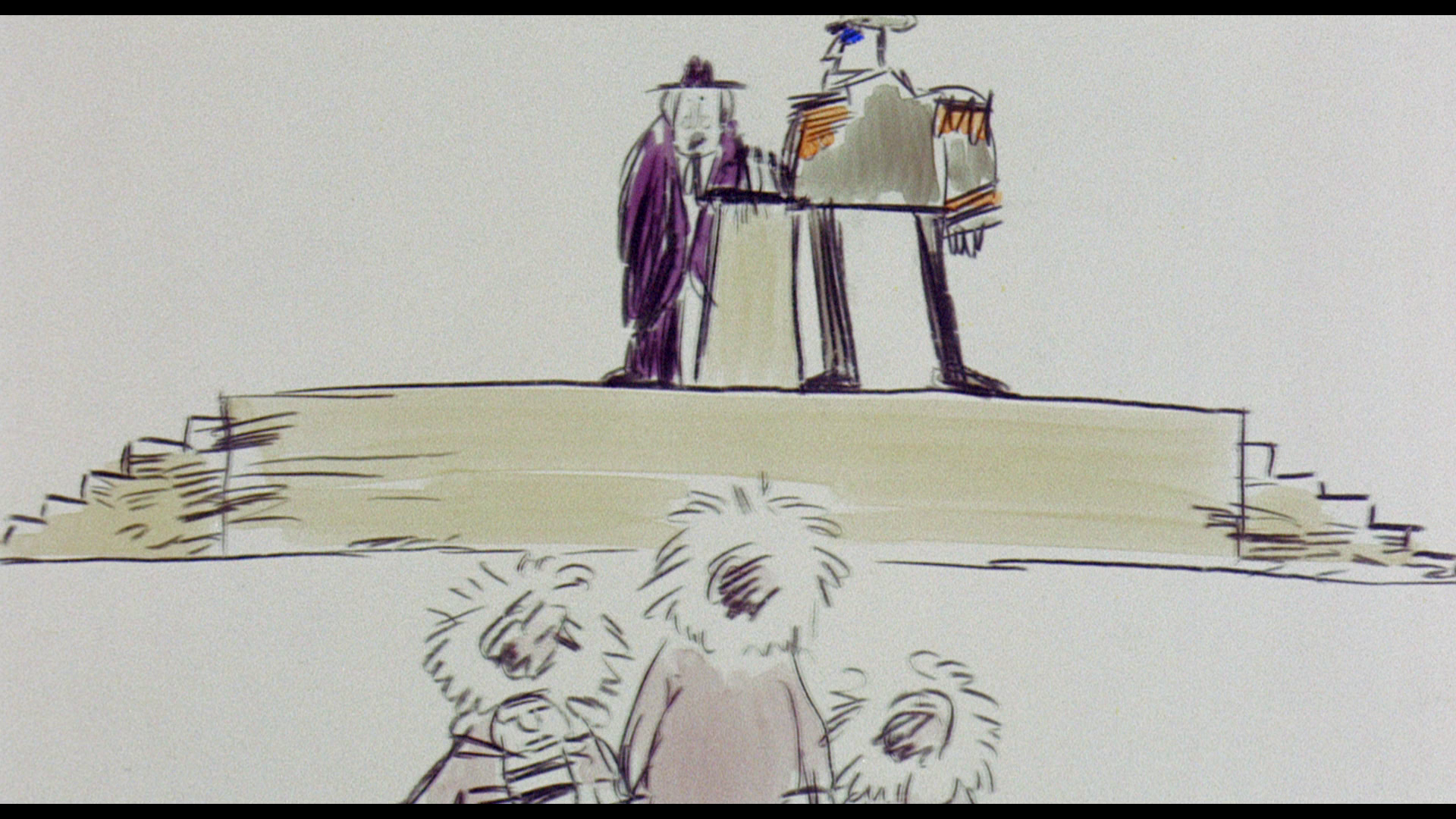

Mathew J Barkowiak and Yuya Kiuchi argue that Gas-s-s-s ‘is a visual, narrative and musical relentless assault of youth and youthful rebellion’ (Barkowiak & Kiuchi, 2015: 96). The picture itself is, they argue, ‘the filmic equivalent of the mantra of: “Don’t trust anyone over thirty”’, and contains a ‘cartoonish, humorous take on that status quo’ alongside ‘both youthful idealism and the cynical exploitation of a still youthful but aging cohort facing a new decade’ (ibid.). It’s a film that offers both ‘a celebration of youth rebellion’ and ‘a cautionary tale of where the counterculture could take us’ (ibid.: 101). Coel is introduced as a harmless prankster, a troublemaker who is able to outwit the establishment. We first see him running across a university campus, carrying a crossbow. He is pursued by a policeman. Coel flees into a church, disguising himself as a priest. The policeman enters the building. ‘Morning, Father. I chased a hippie in here’, he asserts. Coel mimics a ridiculously over-the-top ‘Oirish’ accent and asks the policeman, ‘Oh, well could you describe him, my son?’ ‘Long hair, dirty clothes. Looks like a real troublemaker’, the policeman says. ‘No, there hasn’t been anyone like that around the church for years’, Coel asserts. As he says this, Corman frames him ironically against one of the church’s stained glass windows depicting Christ – another long-haired ‘troublemaker’ of his time – being led away and crucified. It’s a great moment which establishes the film’s countercultural credentials from the get-go. Coel then enters the confessional, where he meets Cilla; he receives confession from her. At this point in the narrative, she is the lab assistant (and lover) of Dr Harvey Murder, and she explains the effects of the gas which is, shortly afterwards, to be accidentally released into the atmosphere: ‘While we were studying the aging process in man’, she says, ‘we discovered a gas that increases the rate of neuron depletion. You see, neurons begin dying off in everyone over the age of twenty-five, and that’s when this gas gets them. It causes death from instant old age’. They are interrupted by the cop, who enters the booth on the other side of the confessional, asking Coel, ‘Father, I have to know, is police brutality really a sin?’ ‘Only on Friday’, Coel tells him. ‘I’m guilty, Father’, the policeman says. ‘For your penance’, Coel responds, ‘you will demonstrate bicycle safety at the Black Panther convention in Mobile, Alabama’.  The picture’s off-kilter approach is signaled from the outset. The pre-titles sequence is a hand-drawn animation and features a military general, with a John Wayne-like drawl, announcing the opening of the new Chemical and Biological Approving Grounds in Alaska – to an audience of Eskimos and seals. A senator, Archer, then mumbles through a speech, and in a parody of political rhetoric only a handful of ‘trigger’ words are audible throughout his speech (‘mumble-mumble, DETERRENT, mumble-mumble, ENEMY, mumble, ANIMALS’), whilst the general jokes, ‘Archer, you crud, where’s the cham-pagne?’ ‘Remember the motto of the chemical-biological warfare unit’, the general tells us, ‘’To you, it may be deadly; but to us, it’s really a gas’. Following this, the film’s titles play out, also animated. The mocking of authority continues in Coel’s encounter with the policeman in the church, discussed above, and compounded when it’s revealed that the experimental gas has ‘escaped’. On the radio, in a moment that further satirises political rhetoric in a manner which is still as relevant today as it was during the film’s production, a government spokesman attempts to deflect stories of the gas’ escape by targeting easy scapegoats: in his speech he asserts that claims the gas has been released accidentally are ‘a malicious rumour pedaled by the limp-wristed cadre of perpetual students, pseudo-intellectuals and biased news media’. The picture’s off-kilter approach is signaled from the outset. The pre-titles sequence is a hand-drawn animation and features a military general, with a John Wayne-like drawl, announcing the opening of the new Chemical and Biological Approving Grounds in Alaska – to an audience of Eskimos and seals. A senator, Archer, then mumbles through a speech, and in a parody of political rhetoric only a handful of ‘trigger’ words are audible throughout his speech (‘mumble-mumble, DETERRENT, mumble-mumble, ENEMY, mumble, ANIMALS’), whilst the general jokes, ‘Archer, you crud, where’s the cham-pagne?’ ‘Remember the motto of the chemical-biological warfare unit’, the general tells us, ‘’To you, it may be deadly; but to us, it’s really a gas’. Following this, the film’s titles play out, also animated. The mocking of authority continues in Coel’s encounter with the policeman in the church, discussed above, and compounded when it’s revealed that the experimental gas has ‘escaped’. On the radio, in a moment that further satirises political rhetoric in a manner which is still as relevant today as it was during the film’s production, a government spokesman attempts to deflect stories of the gas’ escape by targeting easy scapegoats: in his speech he asserts that claims the gas has been released accidentally are ‘a malicious rumour pedaled by the limp-wristed cadre of perpetual students, pseudo-intellectuals and biased news media’.

After the gas is released, we see the responses of various groups of young people. Some of them simply sit passively in a stadium, sharing a joint (‘We decided just to stay stoned, you know, until the whole world blows over’, one of their number asserts); others give mealy-mouthed speeches at rallies; and yet others simply party. Some of the young people take the opportunity to seize power, offering a case of ‘Meet the new boss, same as the old boss’. Attempting to leave the city, Coel and Cilla are stopped by a young man, a former policeman, who has taken it upon himself to issue permits allowing movement in and out the city. He speaks with an exaggerated German accent, reminiscent of a stereotypical Nazi from a war picture, and his attempts to prove his authority are shown to stem from his bitterness at being ridiculed by the hippie youths: ‘In my two years on ze force, you […] creeps oiked at me, abused me. Now I am ze law!’ ‘Say goodbye to Dallas, Cilla’, Coel says, ‘Welve seen that kind of law around here before’. Gas-s-s-s has an episodic, picaresque structure, following Coel and Cilla’s group as they encounter various subcultures, and the film parodies these equally whilst also satirising popular culture. (In its picaresque structure and Coel and Cilla’s encounter with different groups of survivors, watching the picture today seems strangely like watching a full season of the current television series The Walking Dead.) During their flight from Dallas, Coel and Cilla stop by a library. They start a fire. Coel exits the library carrying armfuls of books. ‘My God, you’re not going to burn the books?’, Cilla asks, shocked. ‘The Collected Works of Jacqueline Susann’, Coel tells her, referring to the author of The Valley of the Dolls; ‘Don’t worry: there’s a whole shelf of Harold Robbins novels’.  Many of the groups Coel and Cilla encounter look to various stages in the past for their inspiration. After fleeing Dallas, the couple encounter a group who ride horses and are dressed like cowboys, led by a self-styled Billy the Kid (George Armitage); these young men take Coel and Cilla’s car. Fleeing into the nearest town, Coel and Cilla find young children playing happily in the streets. In a record store, they meet Carlos, who is dressed like Emiliano Zapata, and his friends Marissa, Coralee and Hooper. ‘What say we all sit around and listen to the super sounds of the 1960s, huh?’, Marissa asks, flouncing around the record store. ‘Sound of the 1960s: a gunshot’, Coel responds dryly. Promising the others passage to the new society in New Mexico, Coel and Cilla enlist their help in taking back their care from Billy the Kid and his gang. The sextet visit the hideout of Billy the Kid, a scrapyard, and a gunfight ensues – but instead of firing their guns, the young people call out the names of various actors associated with film Westerns. The trump card, the one that wins the battle for Coel and Cilla’s group, is ‘John Wayne’. Later, Coel and Cilla met a young man who claims to be a Texas Ranger chasing ‘runaway slaves’. ‘Remember, we always get our man’, the young man says. ‘That’s the Mounties’, Coel reminds him, before he and Cilla remind the young man that he’s in New Mexico – not Texas. ‘No wonder I feel so ineffectual’, the young man says, ‘I’m out of my natural environment’. Many of the groups Coel and Cilla encounter look to various stages in the past for their inspiration. After fleeing Dallas, the couple encounter a group who ride horses and are dressed like cowboys, led by a self-styled Billy the Kid (George Armitage); these young men take Coel and Cilla’s car. Fleeing into the nearest town, Coel and Cilla find young children playing happily in the streets. In a record store, they meet Carlos, who is dressed like Emiliano Zapata, and his friends Marissa, Coralee and Hooper. ‘What say we all sit around and listen to the super sounds of the 1960s, huh?’, Marissa asks, flouncing around the record store. ‘Sound of the 1960s: a gunshot’, Coel responds dryly. Promising the others passage to the new society in New Mexico, Coel and Cilla enlist their help in taking back their care from Billy the Kid and his gang. The sextet visit the hideout of Billy the Kid, a scrapyard, and a gunfight ensues – but instead of firing their guns, the young people call out the names of various actors associated with film Westerns. The trump card, the one that wins the battle for Coel and Cilla’s group, is ‘John Wayne’. Later, Coel and Cilla met a young man who claims to be a Texas Ranger chasing ‘runaway slaves’. ‘Remember, we always get our man’, the young man says. ‘That’s the Mounties’, Coel reminds him, before he and Cilla remind the young man that he’s in New Mexico – not Texas. ‘No wonder I feel so ineffectual’, the young man says, ‘I’m out of my natural environment’.

The most significant encounter is with a town that is run by an American football team, the Warriors, who are led by Jason (Alex Wilson). When Coel and Cilla’s group first meet enter the town, the football team are acting as a barbarian horde, pillaging shops and carrying away young women. After meeting with Jason, Coel and Cilla’s group watch as the football team practise drills on a football field; however, these aren’t football drills. Instead, the team are practising smashing walls, stealing televisions, throwing Molotov cocktails and raping women. ‘Tomororw’s the big one’, Jason tells his followers, ‘Tomorrow we’re going to sack El Paso’. Meanwhile, cheerleaders chant: ‘F-F-A-S-C, I-I-S-T. Yay, fascist!’, ‘Hitler, Hitler, he’s our man. If he can’t do it, Jason can’, and ‘2-4-6-8, who do we annihilate? Everybody!’ Coel and Cilla’s group flee from the football team’s grasp, pursued by the football team in their dune buggies – in a bizarre echo of Charles Manson’s ‘dune buggy attack battalion’, a story that would have been ‘breaking’ at the time of the film’s release.  The film makes crude reference to some immediately recognisable stereotypes, especially surrounding the issue of ethnicity. Carlos is a former Black Panther who has a white girlfriend, Marissa, and carries a book and a gun. In response to Coel and Cilla’s querying look, Carlos asserts, ‘Hey, man. We all have our inconsistencies. But that doesn’t stop the revolution, does it?’ When Coel and Cilla’s group wander into a society led by Hell’s Angels who live on a golf course, they are offered menial jobs. Carlos is interrupted in his labour by the leader of the bikers, who says, ‘When I was your colour, son, I made up my mind to be head pro here: I used to go home nights and say…’ He’s interrupted by Carlos, who looks up at the sky and declares, ‘Some day, I’ll own this place’. Later, the group encounter a band of Native Americans – led by a young man who is clearly ‘redfacing’, in the manner of so many Hollywood Westerns, and declaring that he wishes to give Coel and Cilla’s group everything imposed on his culture: smallpox, ‘your silly Columbus Day’, and even the English language. Though clearly intended ironically, with the sequence obviously satirising Hollywood stereotypes rather than Native American culture itself, such moments are potentially challenging to modern sensibilities, as are the occasional jokes about rape which appear here and there throughout the film. In one sequence, Cilla is abducted by three young men who clearly intend to assault her sexually; when the young men struggle to decide who will attack her first, Cilla declares ‘I’m the rapee: I should have something to say’. Pointing at one of the young men, she asserts, ‘You first, and then you. Come on, honey’. It’s a bizarre, arguably challenging moment in a picture which, in some sequences at least, is so postmodern and ironic (and, to be fair, so disrupted by AIP’s interference in the postproduction process) that it seems to be firing grapeshot and hoping, in the process, to hit something or inflame its viewer’s sensibilities. The film makes crude reference to some immediately recognisable stereotypes, especially surrounding the issue of ethnicity. Carlos is a former Black Panther who has a white girlfriend, Marissa, and carries a book and a gun. In response to Coel and Cilla’s querying look, Carlos asserts, ‘Hey, man. We all have our inconsistencies. But that doesn’t stop the revolution, does it?’ When Coel and Cilla’s group wander into a society led by Hell’s Angels who live on a golf course, they are offered menial jobs. Carlos is interrupted in his labour by the leader of the bikers, who says, ‘When I was your colour, son, I made up my mind to be head pro here: I used to go home nights and say…’ He’s interrupted by Carlos, who looks up at the sky and declares, ‘Some day, I’ll own this place’. Later, the group encounter a band of Native Americans – led by a young man who is clearly ‘redfacing’, in the manner of so many Hollywood Westerns, and declaring that he wishes to give Coel and Cilla’s group everything imposed on his culture: smallpox, ‘your silly Columbus Day’, and even the English language. Though clearly intended ironically, with the sequence obviously satirising Hollywood stereotypes rather than Native American culture itself, such moments are potentially challenging to modern sensibilities, as are the occasional jokes about rape which appear here and there throughout the film. In one sequence, Cilla is abducted by three young men who clearly intend to assault her sexually; when the young men struggle to decide who will attack her first, Cilla declares ‘I’m the rapee: I should have something to say’. Pointing at one of the young men, she asserts, ‘You first, and then you. Come on, honey’. It’s a bizarre, arguably challenging moment in a picture which, in some sequences at least, is so postmodern and ironic (and, to be fair, so disrupted by AIP’s interference in the postproduction process) that it seems to be firing grapeshot and hoping, in the process, to hit something or inflame its viewer’s sensibilities.

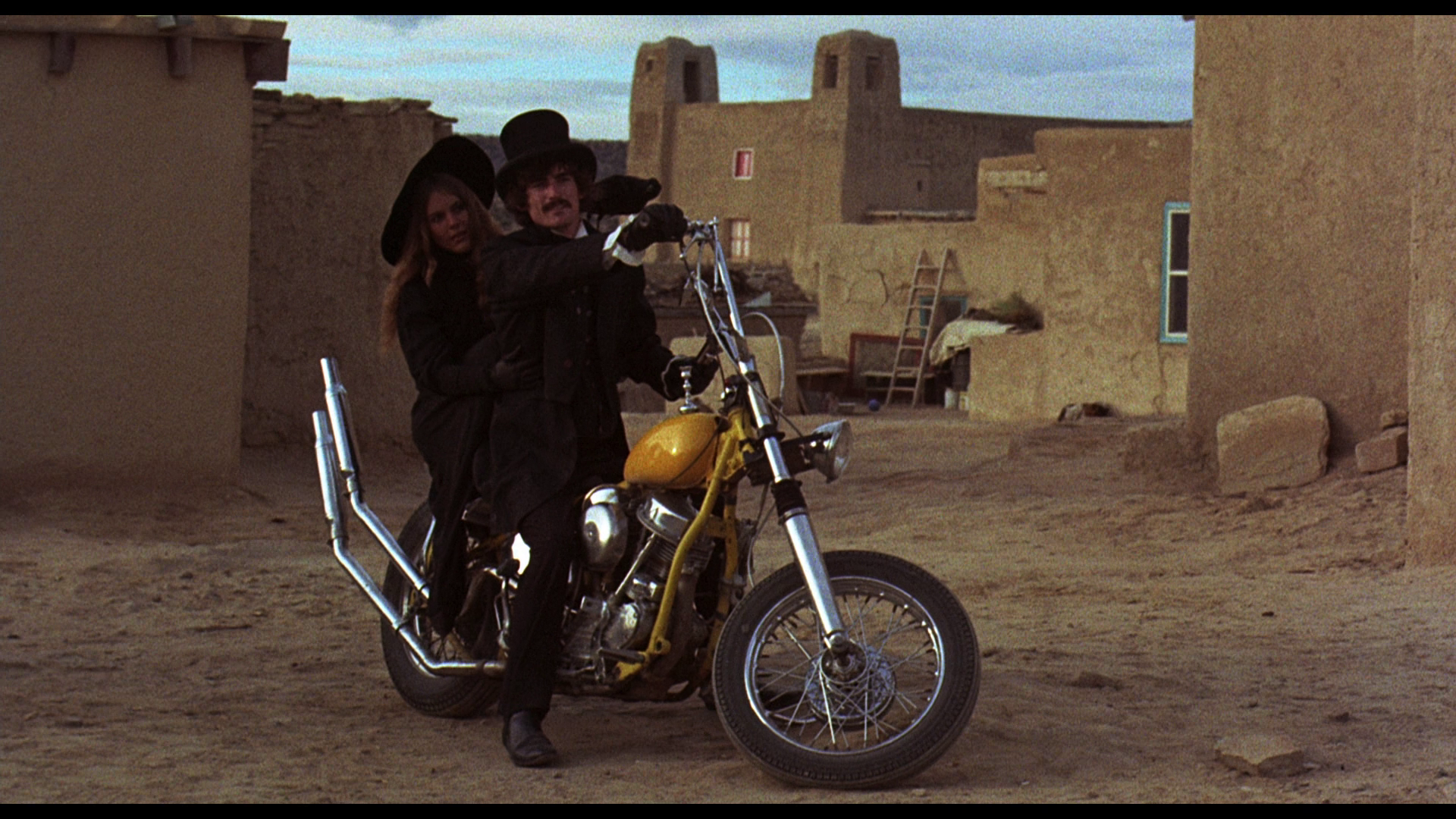

As in The Trip, in Gas-s-s-s Corman slyly pokes fun at Corman’s previous Poe adaptations films, in the form of an Edgar Allan Poe-quoting biker, dressed in period costume and accompanied by an equally Gothic-looking girlfriend, named Lenore after Poe’s famous poem. ‘Edgar’ and Lenore function as a Greek Chorus, appearing at several points in the narrative, watching the action and commenting on it. ‘We’re not wicked’, Cilla asserts during the group’s first encounter with Edgar. ‘Now that you are the sole heir to our world, you will have every opportunity to achieve wickedness’, Edgar tells her, comparing the fallout from the release of the gas with the effects of the Red Death in Poe’s story ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ (adapted for the screen by Corman in 1964), and by extension establishing a likeness between Coel’s group and the people inside Prince Prospero’s castle in that story. Later, after the encounter with the Hell’s Angels, Edgar and Lenore appear again, Edgar declaring, ‘They [Coel’s group] started out full of promise and new ideas. Are they really any different, Lenore?’ ‘They’ve seen the signs’, Lenore responds, ‘They’ve been warned’. ‘Our fear friend Roderick Usher was warned, and yet he persisted’, Edgar says. ‘He was your creation’, Lenore reminds him, ‘You could’ve kept him from falling’. In response to this, Edgar says – in words that perhaps mirrored Corman’s feelings towards his own films, and especially after AIP’s interference in Gas-s-s-s – ‘Sometimes we lose patience, even with our own creations’. ‘Don’t I know it, Edgar’, the voice of God booms from offscreen. At the end of the film, Edgar and Lenore are watching the young people from afar, seated on Edgar’s motorbike (and with Edgar’s pet raven on his shoulder). ‘Aren’t they all going to rape, cheat, steal, lie, fight and kill, Edgar?’, Lenore asks, referring to Coel and his group. ‘What? Nevermore!’ the raven caws comically. As in The Trip, in Gas-s-s-s Corman slyly pokes fun at Corman’s previous Poe adaptations films, in the form of an Edgar Allan Poe-quoting biker, dressed in period costume and accompanied by an equally Gothic-looking girlfriend, named Lenore after Poe’s famous poem. ‘Edgar’ and Lenore function as a Greek Chorus, appearing at several points in the narrative, watching the action and commenting on it. ‘We’re not wicked’, Cilla asserts during the group’s first encounter with Edgar. ‘Now that you are the sole heir to our world, you will have every opportunity to achieve wickedness’, Edgar tells her, comparing the fallout from the release of the gas with the effects of the Red Death in Poe’s story ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ (adapted for the screen by Corman in 1964), and by extension establishing a likeness between Coel’s group and the people inside Prince Prospero’s castle in that story. Later, after the encounter with the Hell’s Angels, Edgar and Lenore appear again, Edgar declaring, ‘They [Coel’s group] started out full of promise and new ideas. Are they really any different, Lenore?’ ‘They’ve seen the signs’, Lenore responds, ‘They’ve been warned’. ‘Our fear friend Roderick Usher was warned, and yet he persisted’, Edgar says. ‘He was your creation’, Lenore reminds him, ‘You could’ve kept him from falling’. In response to this, Edgar says – in words that perhaps mirrored Corman’s feelings towards his own films, and especially after AIP’s interference in Gas-s-s-s – ‘Sometimes we lose patience, even with our own creations’. ‘Don’t I know it, Edgar’, the voice of God booms from offscreen. At the end of the film, Edgar and Lenore are watching the young people from afar, seated on Edgar’s motorbike (and with Edgar’s pet raven on his shoulder). ‘Aren’t they all going to rape, cheat, steal, lie, fight and kill, Edgar?’, Lenore asks, referring to Coel and his group. ‘What? Nevermore!’ the raven caws comically.

For Corman, Gas-s-s-s ‘was a pretty personal statement’: although he admits that he was ‘certainly past my youth at the time’, from The Wild Angels onwards Corman geared his films ‘toward a sympathetic portrayal of the counter-culture’ owing to the fact that he ‘had been something of a supporter of the youth culture’ of the era (Corman, quoted in Naha, 1984: 132). However, by the time that Corman made Gas-s-s-s he was ‘beginning to get a little disillusioned’, and he intended the film to ‘be sympathetic toward our lead gang of kids’ whilst also ‘show[ing] that I was beginning to suspect that all of the ideas being spouted by the counter-culture and all of the dreams were not totally rooted in reality’ (Corman, quoted in ibid.). He aimed, within the world depicted in the film, to ‘literally give youth the world they desired and, then, make a cautionary statement about how youth might not be able to handle it as perfectly as they anticipated’ (Corman, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). For Corman, Gas-s-s-s ‘was a pretty personal statement’: although he admits that he was ‘certainly past my youth at the time’, from The Wild Angels onwards Corman geared his films ‘toward a sympathetic portrayal of the counter-culture’ owing to the fact that he ‘had been something of a supporter of the youth culture’ of the era (Corman, quoted in Naha, 1984: 132). However, by the time that Corman made Gas-s-s-s he was ‘beginning to get a little disillusioned’, and he intended the film to ‘be sympathetic toward our lead gang of kids’ whilst also ‘show[ing] that I was beginning to suspect that all of the ideas being spouted by the counter-culture and all of the dreams were not totally rooted in reality’ (Corman, quoted in ibid.). He aimed, within the world depicted in the film, to ‘literally give youth the world they desired and, then, make a cautionary statement about how youth might not be able to handle it as perfectly as they anticipated’ (Corman, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original).

Joseph Maddrey has suggested that The Trip was ‘the final peak of Corman’s career as a director’ (Maddrey, 2004: 119). Following the trials and tribulations of bringing Gas-s-s-s to the screen and the level of interference from AIP, Corman only officially directed two more feature films, preferring to work instead as a producer of other people’s pictures. The conflict between Corman and AIP that culminated in Corman’s departure from AIP following their handling of Gas-s-s-s had begun with The Wild Angels, which AIP had re-edited in 1966: according to Corman, AIP ‘made a bizarre cut in Angels that made no sense whatsoever. They changed the pan shot outside the church, before the orgy sequence, to a shot of a sign that said it was a funeral home. It wrecked the shot’ (Corman, quoted in Stevens, 2003: 71). The Trip featured similar interference from AIP, who added a prologue and changed the ending in order to add an anti-drugs slant to Corman’s balanced depiction of the experience of taking LSD. (Signal One’s recent Blu-ray release of that title removes that prologue and restores the original ending.) Gas-s-s-s was more drastically re-edited, with many sequences excised and a number of characters omitted from the final cut of the picture. To make matters worse, the picture was also ‘buried’ by AIP, who denied the film ‘a proper marketing campaign’ owing to anxiety surrounding the content of the film and its relationship with then-current events such as the shootings at Kent State University (Krutnik, 2007: 223). Corman himself stated in a 1973 interview that ‘AIP became very, very frightened of the picture’, re-editing it whilst Corman was shooting another film in Europe, ‘taking out “God,” one of the major characters, and eliminating the entire end of the picture. They took every questionable or controversial point out of the picture; and that was what the picture was all about. So it became an extremely innocuous and slightly meaningless picture. And that’s what went out. No one ever saw the picture as it was made—and the picture did not do well’ (Corman, quoted in McCarthy & Flynn, 1973: 77).  Coel and Cilla’s group’s journey ends at the destination of Carlos and his compadres: a New Mexico town that is run as a commune, that most utopian of societies (at the time of the film’s production). Upon arrival, Coel, Cilla and the others are greeted by a young man who tells them ‘You can all make a contribution by doing what you enjoy doing’, and offering, ‘There’s food, shelter, friendship and love here. There’s no violence. None. No thought of it. Only love’. Coel quickly takes a position teaching young children. He tells the children of LSD, suggesting that before the gas escaped scientists were attempting to make a drug that would allow its user to experience fantastic hallucinations. (In Coel’s refusal to moralise about LSD, the viewer might be reminded of Corman’s previous film, The Trip, whose objectivity about LSD cause problems both within AIP and, in the UK, with the BBFC.) One particularly bright child, Soren, declares ‘What you’re saying is that our largest drug manufacturers would become film studios’. Coel corrects the boy slightly, offering the film’s most pointed criticism of Hollywood, ‘I rather thought of it as some of our largest film studios becoming drug pushers’. Coel and Cilla’s group’s journey ends at the destination of Carlos and his compadres: a New Mexico town that is run as a commune, that most utopian of societies (at the time of the film’s production). Upon arrival, Coel, Cilla and the others are greeted by a young man who tells them ‘You can all make a contribution by doing what you enjoy doing’, and offering, ‘There’s food, shelter, friendship and love here. There’s no violence. None. No thought of it. Only love’. Coel quickly takes a position teaching young children. He tells the children of LSD, suggesting that before the gas escaped scientists were attempting to make a drug that would allow its user to experience fantastic hallucinations. (In Coel’s refusal to moralise about LSD, the viewer might be reminded of Corman’s previous film, The Trip, whose objectivity about LSD cause problems both within AIP and, in the UK, with the BBFC.) One particularly bright child, Soren, declares ‘What you’re saying is that our largest drug manufacturers would become film studios’. Coel corrects the boy slightly, offering the film’s most pointed criticism of Hollywood, ‘I rather thought of it as some of our largest film studios becoming drug pushers’.

The film is here presented uncut, with a running time of 77:30 mins.

Video

There’s some beautiful photography within the picture. After the hand-drawn animation of the precredits sequence, the film proper begins with shots of city streets, presumably shot in the Corman run-and-gun style, without permits; a telephoto lens is used to give the suggestion of visual eavesdropping, the camera racking focus from a crowd in the distance to pick out one man lighting a cigarette in the midground, the depth of field isolating him within the frame. It’s an image that’s reminiscent of the colour street photography of Saul Leiter or Fred Herzog. After the gas is released, the camera is mobile – presumably mounted in or on a moving vehicle – and picks out a lonely dog tied to a lamppost, its human owners presumably dead, and an elderly couple seated on the pavement, the woman cradling the man in her arms. There’s some beautiful photography within the picture. After the hand-drawn animation of the precredits sequence, the film proper begins with shots of city streets, presumably shot in the Corman run-and-gun style, without permits; a telephoto lens is used to give the suggestion of visual eavesdropping, the camera racking focus from a crowd in the distance to pick out one man lighting a cigarette in the midground, the depth of field isolating him within the frame. It’s an image that’s reminiscent of the colour street photography of Saul Leiter or Fred Herzog. After the gas is released, the camera is mobile – presumably mounted in or on a moving vehicle – and picks out a lonely dog tied to a lamppost, its human owners presumably dead, and an elderly couple seated on the pavement, the woman cradling the man in her arms.

Taking up approximately 19Gb on its disc, the presentation of the film is in the picture’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. It’s a 1080p presentation and uses the AVC codec. Contrast is beautiful, offering a very nicely balanced image, with good, deep blacks where they are needed. Much of the film was shot in the areas with harsh sunlight, and within the photography there are lots of reflexive lens flares and stunning shots of characters lit by the sun from behind. Many sequences also feature a golden hue and the type of light which suggests they were shot at ‘magic hour’. All of this is communicated nicely in this presentation. The image, as presented on this disc, is detailed and free of damage and debris. A strong encode ensures the presentation has an organic, film-like appearance.    NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track This is rich and problem free. The optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are clear and easy to read too.

Extras

The disc includes two audio interviews with Roger Corman. Both are presented as audio accompaniment to the main feature presentation (ie, as alternate audio tracks to it). The first of these was recorded at the NFT in 1970; The second was recorded at the same venue in 1991. Both last just over an hour. The disc includes two audio interviews with Roger Corman. Both are presented as audio accompaniment to the main feature presentation (ie, as alternate audio tracks to it). The first of these was recorded at the NFT in 1970; The second was recorded at the same venue in 1991. Both last just over an hour.

- ‘Counter-Culture Corman’ (9:45). This short piece features Corman talking about his turn away from the period setting of the Poe films he made from AIP; ‘what I wanted to do was get out of the studio […] and I wanted to get into the streets and shoot some contemporary subject matter’, he says. Film historians Ted Newsom, Constantine Nasr, Gary Smith and Chris Poggiali are interviewed too. The trio, interviewed separately, comment on the first of Corman’s post-Poe pictures, 1966’s Hell’s Angels picture The Wild Angels. With The Trip, Corman ‘wanted to move away from the working-class counter-culture […] to a higher level’, showing a middle-class man’s encounter with counter-cultural ideas (via Peter Fonda’s character’s experimentation with LSD). Finally, the commentators reflect on Gas-s-s-s and AIP’s (mis)handling of it. It’s an interesting piece but, given the number of contributors and the coverage of The Wild Angels, The Trip and Gas-s-s-s, feels much too short, with topics and issues glanced over all too briefly. - Lobby Cards, Press Book and Stills Gallery (0:28). - Trailer (3:08).

Overall

Gas-s-s-s is a strange, unwieldy picture. It strives for satire of Dr Strangelove; Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) proportions, whilst at the same time its freewheeling approach to narrative and its focus on youth cultures and the collapse of society has echoes of Jean-Luc Godard’s impenetrable-for-some 1967 picture Weekend. In many ways, the film’s most barbed attacks seem directed at Hollywood and its stereotypes: the parody of ‘redfacing’ and the depiction of Native Americans in films, the constant reference to cinema’s stereotypes surrounding gender, youth and ethnicity, and Coel’s comparison towards the end of the picture with Hollywood filmmakers and drug pushers. Gas-s-s-s is a strange, unwieldy picture. It strives for satire of Dr Strangelove; Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) proportions, whilst at the same time its freewheeling approach to narrative and its focus on youth cultures and the collapse of society has echoes of Jean-Luc Godard’s impenetrable-for-some 1967 picture Weekend. In many ways, the film’s most barbed attacks seem directed at Hollywood and its stereotypes: the parody of ‘redfacing’ and the depiction of Native Americans in films, the constant reference to cinema’s stereotypes surrounding gender, youth and ethnicity, and Coel’s comparison towards the end of the picture with Hollywood filmmakers and drug pushers.

‘New’ viewers would be advised to check out Signal One’s release of The Trip first, which is arguably the best of Corman’s films about the counterculture. Gas-s-s-s’ scattershot approach won’t be to all tastes, and in all honesty the picture is something of a mess. This, it’s been claimed, is owing to AIP’s interference in postproduction. However, given the absence of any other version of the film it’s hard to say whether the film could ever have been more focused. Nevertheless, the picture a fascinating time capsule, offering a profile of the various youth cultures of the time; its genuinely funny moments are mitigated by some wild misfires. This release from Signal One, continuing their run of very impressive Blu-ray discs, contains a pleasing presentation of the film and some very good supporting material which helps to provide an all-important context for the picture. References: Barkowiak, Mathew J & Kiuchi, Yuya, 2015: The Music of Counterculture Cinema: A Critical Study of 1960s and 1970s Soundtracks. London: McFarland Krutnik, Frank, 2007: “Un-American” Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. Rutgers University Press McCarthy, Todd & Flynn, Charles, 1973: ‘Roger Corman Interview’. In: Nasr, Constantine (ed), 2011: Roger Corman: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 72-82 Maddrey, Joseph, 2004: Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film. London: McFarland Naha, Ed, 1984: ‘Cautionary Fables: An Interview with Roger Corman’. In: Nasr, Constantine (ed), 2011: Roger Corman: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 130-5 Stevens, Brad, 2003: Monte Hellman: His Life and Films. London: McFarland

|

|||||

|