|

The Film

Compulsion (Richard Fleischer, 1959) Compulsion (Richard Fleischer, 1959)

Based on the infamous Leopold-Loeb murder case of 1924, Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion (1959) features a bravura performance from Orson Welles as Jonathan Wilk, a fictionalised version of Clarence Darrow, Leopold and Loeb’s defence attorney. The film was adapted from the Broadway play of the same title (which was in turn adapted by Meyer Levin from his own novel of 1956) with Dean Stockwell reprising his role as Judd Steiner, one of the killers (a clear substitute for Leopold); Roddy McDowall, who in the Broadway production had played the other murderer, Artie Straus (Loeb), was replaced in Fleischer’s film by Bradford Dillman.

Taking place in 1924, Compulsion begins with the fallout from the murder of ‘little Paulie Kessler’, a 14 year old boy who has gone missing, initially presumed kidnapped. When Paulie’s body is discovered, student and aspiring journalist Sid Brooks (Martin Milner) is sent by the Globe to speak with the coroner. Brooks notices that a pair of eyeglasses found with the body are much to large to have belonged to Paulie; the police discover that these eyeglasses have a specially manufactured hinge and could only belong to Judd Steiner, the youngest son of a wealthy family. Judd and Sid know one another; fascinated by the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche to the extent that he argues vehemently with his university professor, Judd is in a relationship with Artie Straus, who also comes from a wealthy family, but Judd seems desperate to ‘prove’ that he is heterosexual through dallying with Ruth Evans (Diane Varsi), whom Sid also knows.

Artie seems to assist the police investigation and points the finger for Paulie’s murder at Judd. Under questioning, Judd implicates Artie in the murder. The two young men are put on trial for the murder of the boy; after both Judd and Artie are declared legally sane and, as a consequence, face the death penalty, Judd and Artie’s families appeal to Jonathan Wilk, a defence attorney known for his staunch stance against capital punishment. Wilk enters a plea of ‘guilty’ so that Judd and Artie may be tried by a judge instead of a jury, thus giving them a better chance of receiving life imprisonment over the death penalty. Wilk’s argument is predicated on the suggestion that had Judd and Artie been from less privileged backgrounds and the case not become a media circus, the death penalty would never have been suggested as a fit punishment for their crime. Artie seems to assist the police investigation and points the finger for Paulie’s murder at Judd. Under questioning, Judd implicates Artie in the murder. The two young men are put on trial for the murder of the boy; after both Judd and Artie are declared legally sane and, as a consequence, face the death penalty, Judd and Artie’s families appeal to Jonathan Wilk, a defence attorney known for his staunch stance against capital punishment. Wilk enters a plea of ‘guilty’ so that Judd and Artie may be tried by a judge instead of a jury, thus giving them a better chance of receiving life imprisonment over the death penalty. Wilk’s argument is predicated on the suggestion that had Judd and Artie been from less privileged backgrounds and the case not become a media circus, the death penalty would never have been suggested as a fit punishment for their crime.

Compulsion differs quite strongly from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), which had also fictionalised the Leopold-Loeb case and itself had been based on a play (the 1929 play of the same title by Patrick Hamilton). Linda Bradley Salaman has argued that Rope ‘sanitises’ the real-life murder case by making the victim a contemporary of the two killers rather than the fourteen year old boy he was in real life (Salaman, 2007: 20). Unlike the Hitchcock picture, Compulsion doesn’t shy away from the facts in the case on which it was based: Salaman notes that Fleischer’s film ‘cut so close to the bone that Leopold initially sued writer, producers, publicists and theatre-owners for breach of privacy’ (ibid.). In Compulsion, the victim is quite clearly a young boy, with the dialogue reminding the viewer of this fact by repeatedly referring to the dead child as ‘little Paulie’ (ibid.). William Hare has suggested that the differences between Compulsion, which builds towards Wick’s impassioned plea against the death penalty, and Rope are owing to the different agendas within the periods in which the respective films were made: Hitchcock’s Rope was made in the period that followed the Second World War and ‘reflected the compelling moral issues’ of that immediate post-war era (including Hitchcock’s own sense of ‘helplessness’ during the war), whereas Fleischer’s Compulsion was made at the end of the 1950s, when the ‘death penalty was a burning issue’ (Hare, 2007: 145). Where Hitchcock’s film ‘focused on madness from the standpoint of genius-level intellects embracing nihilistic superiority’, in Compulsion Fleischer ‘focused on the issue of the death penalty’ almost exclusively (ibid.).

Fittingly for an adaptation of Levin’s ‘documentary novel’ – the first of its kind, predating Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1965) and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) – Fleischer’s film is almost like a semidocumentary film noir. Fleischer would subsequently gain a reputation as a director of films based on true crimes, with pictures that had an unflinching, almost semidocumentary quality: by the time of the production of Compulsion, Fleischer had already made one such film – The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, based on the Evelyn Nesbit case of 1906 – and his later films included, of course, The Boston Strangler (1968) and the Reginald Christie picture 10 Rillington Place (1970). Fittingly for an adaptation of Levin’s ‘documentary novel’ – the first of its kind, predating Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1965) and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979) – Fleischer’s film is almost like a semidocumentary film noir. Fleischer would subsequently gain a reputation as a director of films based on true crimes, with pictures that had an unflinching, almost semidocumentary quality: by the time of the production of Compulsion, Fleischer had already made one such film – The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, based on the Evelyn Nesbit case of 1906 – and his later films included, of course, The Boston Strangler (1968) and the Reginald Christie picture 10 Rillington Place (1970).

In Compulsion, the widescreen compositions negate this impression slightly (and the decision to shoot the picture in anamorphic widescreen seems a slightly strange one), but the film takes a matter-of-fact approach: absent of non-diegetic music (with the exception of the opening and closing titles sequences), sequences are filmed as if eavesdropping on the narrative events. Fleischer had of course already made a handful of semidocumentary films noir, including Bodyguard (1948), Trapped (1949), Follow Me Quietly (1949) and Armored Car Robbery (1950). This semidocumentary approach would become even more pronounced in Fleischer’s film about Albert DeSalvo, The Boston Strangler, and perhaps originates in Fleischer’s early work as a documentary filmmaker for RKO.

Compulsion is structured in a manner that viewers of the long-running American crime drama Law & Order (1990-2010) will recognise immediately. Beginning after the murder of ‘little Paulie’, the first half of the picture deals with the fallout from the crime and the circumstances leading to the arrest of both Judd and Artie. The second half of the film moves the action to the courtroom and focuses on the arrival of Jonathan Wilk and his attempts to prevent the two youths from being executed for the murder of the Kessler boy.

Judd and Artie, for their part, have a strange relationship. As the film begins, they are shown exiting a house from which Judd has stolen a typewriter. ‘When we made the deal, you said you would take orders’, Artie taunts Judd after they exit the house in the opening scene, ‘You said you wanted me to command you’. Artie is clearly the dominant partner, with the frustrated and childlike Judd – who is prone to tantrums – offering himself as subservient to his friend and lover. ‘Please, Artie, I’ll do anything you say’, Judd pleads, ‘Something perfect, something brilliant. The true test of the superior intellect with every little detail worked out [….] And no reason for it except to show that we can do it’. The Motion Picture Production Code prevented the film from stating explicitly that Judd Steiner and Artie Strauss were gay, though beginning with this opening sequence, in a number of scenes the film contains some not-so-subtle hints in this direction. Throughout Compulsion, Judd seems to struggle with his sexuality, in thrall to Artie whilst seemingly desperate to ‘prove’ himself to be heterosexual. Meanwhile, Judd’s brother Max (Richard Anderson) hints at the true nature of Judd’s relationship with Artie when Max and Artie have an argument: Max suggests that Judd has been ‘up to some funny business with Artie’, and observes that ‘Outside of Artie and your [stuffed] birds, you don’t give a damn about anything else in the world’. Max warns Judd against ‘making a jackass out of yourself over Artie Straus’ and asks his younger brother ‘Don’t you ever go to a baseball game or chase girls or anything?’ (Later, when Judd arranges a date with Ruth, Artie taunts him by asking, ‘Are you ditching me for some girl?’) Following their arrest by the police, Judd and Artie are referred to by a reporter as ‘a couple of powder puffs’ who are ‘too afraid of their fathers to do anything else’. Judd and Artie, for their part, have a strange relationship. As the film begins, they are shown exiting a house from which Judd has stolen a typewriter. ‘When we made the deal, you said you would take orders’, Artie taunts Judd after they exit the house in the opening scene, ‘You said you wanted me to command you’. Artie is clearly the dominant partner, with the frustrated and childlike Judd – who is prone to tantrums – offering himself as subservient to his friend and lover. ‘Please, Artie, I’ll do anything you say’, Judd pleads, ‘Something perfect, something brilliant. The true test of the superior intellect with every little detail worked out [….] And no reason for it except to show that we can do it’. The Motion Picture Production Code prevented the film from stating explicitly that Judd Steiner and Artie Strauss were gay, though beginning with this opening sequence, in a number of scenes the film contains some not-so-subtle hints in this direction. Throughout Compulsion, Judd seems to struggle with his sexuality, in thrall to Artie whilst seemingly desperate to ‘prove’ himself to be heterosexual. Meanwhile, Judd’s brother Max (Richard Anderson) hints at the true nature of Judd’s relationship with Artie when Max and Artie have an argument: Max suggests that Judd has been ‘up to some funny business with Artie’, and observes that ‘Outside of Artie and your [stuffed] birds, you don’t give a damn about anything else in the world’. Max warns Judd against ‘making a jackass out of yourself over Artie Straus’ and asks his younger brother ‘Don’t you ever go to a baseball game or chase girls or anything?’ (Later, when Judd arranges a date with Ruth, Artie taunts him by asking, ‘Are you ditching me for some girl?’) Following their arrest by the police, Judd and Artie are referred to by a reporter as ‘a couple of powder puffs’ who are ‘too afraid of their fathers to do anything else’.

In the opening sequence, leaving the house in his car, Artie drives the vehicle at speed towards a drunk in the road. At the last minute, Artie steers the car away. ‘We’d have been murderers’, Artie boasts, ‘And you know why I tried it, Juddsie? Because I damn well felt like it’. In his university classes, Judd engages in impassioned espousal of Nietzsche’s ideas, asserting to the bemused Professor McKinnon (Jack Raine) that he ‘must agree with Nietzsche’. ‘All men are governed by laws’, McKinnon responds, ‘And had Nietzsche been a lawyer instead of a German philosopher, he would have known that too’. Meanwhile, Judd’s fascination with taxidermy and ornithology lead him to being seen as kooky by his contemporaries: at one point, Ruth tells Sid that ‘Just because he [Judd] can speak about something besides sex, you, Artie and all the rest of you speak about him as if he’s some kind of freak’. However, when Judd takes Ruth on a date, he is torn over his urge to attack her. Prior to this, Judd and Ruth discuss the murder of ‘little Paulie’, with Judd asserting that ‘Murder’s nothing. It’s just a simple experience. Murder and rape. Do you know what beauty there is in evil?’ He assaults Ruth, pinning her to the ground and demanding, ‘Are you afraid of me?’ ‘I’m afraid for you, Judd’, Ruth responds. This causes Judd to release Ruth in a moment of epiphany: ‘Oh my God’, he asserts, ‘I’m so ashamed’. In the opening sequence, leaving the house in his car, Artie drives the vehicle at speed towards a drunk in the road. At the last minute, Artie steers the car away. ‘We’d have been murderers’, Artie boasts, ‘And you know why I tried it, Juddsie? Because I damn well felt like it’. In his university classes, Judd engages in impassioned espousal of Nietzsche’s ideas, asserting to the bemused Professor McKinnon (Jack Raine) that he ‘must agree with Nietzsche’. ‘All men are governed by laws’, McKinnon responds, ‘And had Nietzsche been a lawyer instead of a German philosopher, he would have known that too’. Meanwhile, Judd’s fascination with taxidermy and ornithology lead him to being seen as kooky by his contemporaries: at one point, Ruth tells Sid that ‘Just because he [Judd] can speak about something besides sex, you, Artie and all the rest of you speak about him as if he’s some kind of freak’. However, when Judd takes Ruth on a date, he is torn over his urge to attack her. Prior to this, Judd and Ruth discuss the murder of ‘little Paulie’, with Judd asserting that ‘Murder’s nothing. It’s just a simple experience. Murder and rape. Do you know what beauty there is in evil?’ He assaults Ruth, pinning her to the ground and demanding, ‘Are you afraid of me?’ ‘I’m afraid for you, Judd’, Ruth responds. This causes Judd to release Ruth in a moment of epiphany: ‘Oh my God’, he asserts, ‘I’m so ashamed’.

The fact that the murder is committed without a conventional motive (‘And no reason for it except to show that we can do it’, as Judd asserts near the start of the picture) makes the killing of ‘little Paulie’ all the more abhorrent. With the capture of Judd and Artie, the death sentence seems a foregone conclusion. Judd’s IQ is off the scale, but both he and Artie have, we are told, the emotional maturity of a seven year old child. Towards the second half of the film, some of the dialogue takes on an almost didactic quality as the characters discuss the death penalty. ‘Ruth, they’re murderers’, Sid reasons, ‘How do you think the Kessler family feels?’ ‘I know how they must feel’, Ruth protests, ‘But I can’t help feeling sorry for Judd and for Artie’. ‘Sorry for them? Ruth, they plotted a cold-blooded killing and went through with it like an experiment in chemistry’, Sid asserts. In response to this, Ruth tells Sid that Judd attacked her, asserting that ‘He was like a child; a sick, frightened child’. Meanwhile, a journalist refers to Judd and Artie simply as ‘Two evil minds that don’t deserve to live any longer’.

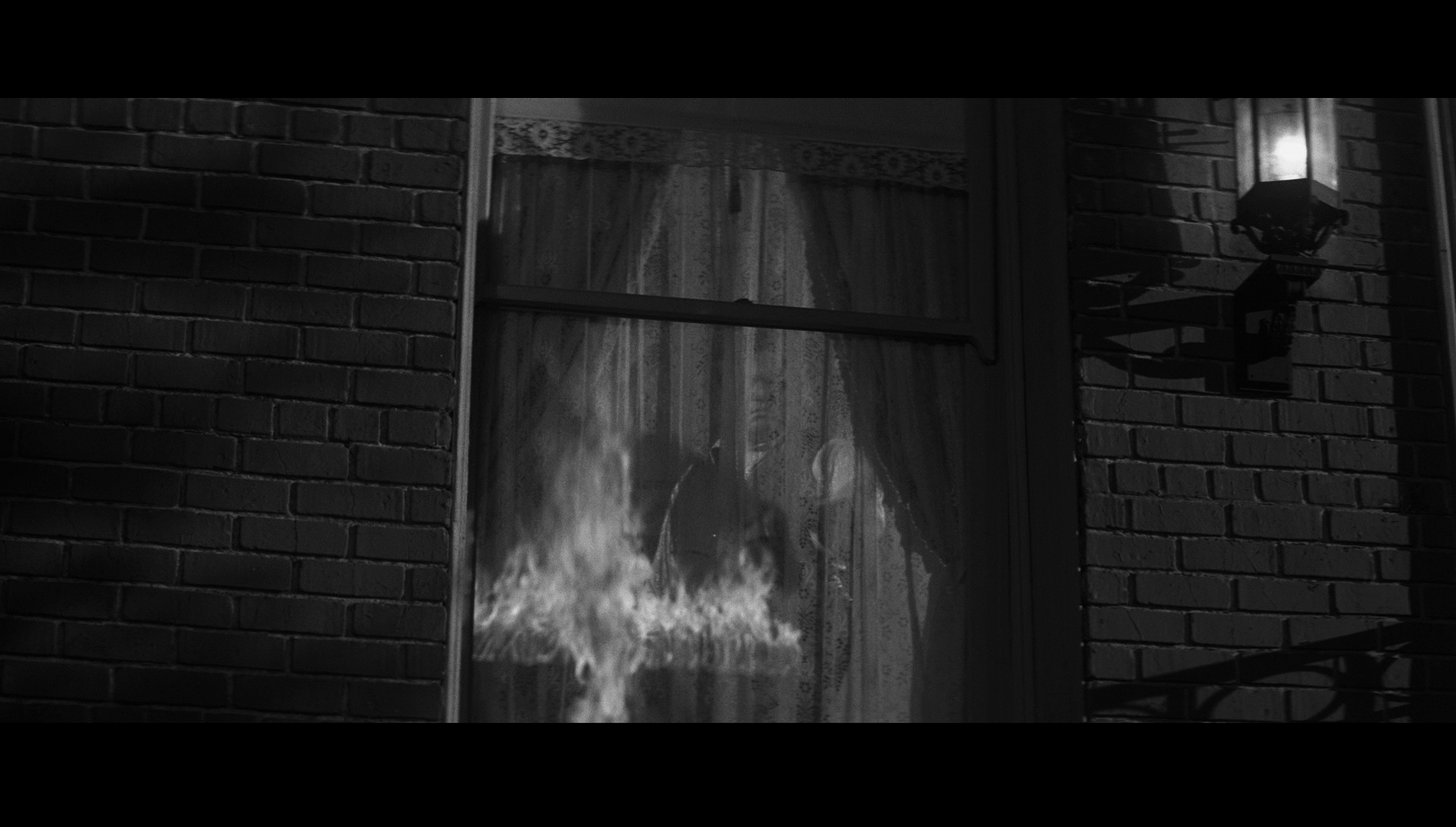

Into this mix, Wilk is introduced as a character who has ‘fought capital punishment all his life’, and upon his arrival he declares that ‘I suppose I ought to consider it a minor victory that the boys weren’t hanged before I got here’. One night, he awakens to find the Ku Klux Klan burning a cross outside, and when the police offer him protection, Wilk responds dryly that ‘I wouldn’t worry your heads over the kind of folks whose reaction to an emotional situation is to pull a sheet over their head’. The association of the Ku Klux Klan with the pro-death penalty rhetoric within the film undermines that point of view immediately, giving Wilk the moral high ground. Having been hired by the parents of Judd and Artie ‘on your reputation as a manipulator of juries’, Wilk insists that the only way to spare Judd and Artie is to plead guilty and have the case tried by a judge rather than a jury. He condemns the hyperbole associated with the case, suggesting that in his forty-five years experience ‘I did not try a case that the State’s Attorney did not say was the most cold-blooded, inexcusable case ever’. Whilst acknowledging that ‘there was no excuse for the killing of little Paulie Kessler, there was also no reason for it’, Wilk argues that if Judd and Artie had been from impoverished backgrounds, a wealth of people would call for them to be given life imprisonment instead of the death penalty – and that, in effect, the pair are being tried by the media and people’s prejudices. Into this mix, Wilk is introduced as a character who has ‘fought capital punishment all his life’, and upon his arrival he declares that ‘I suppose I ought to consider it a minor victory that the boys weren’t hanged before I got here’. One night, he awakens to find the Ku Klux Klan burning a cross outside, and when the police offer him protection, Wilk responds dryly that ‘I wouldn’t worry your heads over the kind of folks whose reaction to an emotional situation is to pull a sheet over their head’. The association of the Ku Klux Klan with the pro-death penalty rhetoric within the film undermines that point of view immediately, giving Wilk the moral high ground. Having been hired by the parents of Judd and Artie ‘on your reputation as a manipulator of juries’, Wilk insists that the only way to spare Judd and Artie is to plead guilty and have the case tried by a judge rather than a jury. He condemns the hyperbole associated with the case, suggesting that in his forty-five years experience ‘I did not try a case that the State’s Attorney did not say was the most cold-blooded, inexcusable case ever’. Whilst acknowledging that ‘there was no excuse for the killing of little Paulie Kessler, there was also no reason for it’, Wilk argues that if Judd and Artie had been from impoverished backgrounds, a wealth of people would call for them to be given life imprisonment instead of the death penalty – and that, in effect, the pair are being tried by the media and people’s prejudices.

Appealing to Christian values of ‘charity, faith and understanding’, Wilk suggests to the courtroom that executing the boys will be nothing more than a sop to a media furore: ‘If you hang these boys it will mean that in this land of ours’, Wilk suggests, ‘a court of law could not keep but bow down to public opinion’. The state’s decision to execute Judd and Artie ‘must be your own cool, premeditated act’ that is equivalent to the murder of ‘little Paulie’ itself: ‘We are told it was a cold blooded killing because they planned and schemed’, Wilk tells the courtroom in reference to the killing of the Kessler child, ‘yet here are officers of the state who for months have planned and schemed and contrived to take these boys’ lives’.

Video

Presented in Compulsion’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1, this superb 1080p presentation (using the AVC codec) is based on a new 4k restoration and fills 20Gb of space on its disc. It features a crisp, detailed image, clean and free of damage and debris. The monochrome photography is rendered with excellent contrast levels, offering deep shadows and strong, defined mid-tones. It’s an utterly excellent presentation, carried by a strong encode that retains a natural film-like structure. Presented in Compulsion’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1, this superb 1080p presentation (using the AVC codec) is based on a new 4k restoration and fills 20Gb of space on its disc. It features a crisp, detailed image, clean and free of damage and debris. The monochrome photography is rendered with excellent contrast levels, offering deep shadows and strong, defined mid-tones. It’s an utterly excellent presentation, carried by a strong encode that retains a natural film-like structure.

The film is uncut and runs for 103:10 mins.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 track and a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. Both are in English. Both tracks are clean and clear. The 5.1 track has added separation which makes it more dramatic in places but it’s artificial and the sound separation is both unnecessary and arguably feels out of place in a picture of this vintage. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided. These are easy to read but contained one or two very minor grammatical errors (a confusion of ‘who’s’ with ‘whose’ at 75 minutes into the picture, for example).

Extras

The disc includes:

- Richard Fleischer Guardian Interview (1981). Recorded at the NFT, Fleischer is interviewed by Adrian Turner. The interview is presented as an audio recording which accompanies the main feature, in the manner of an audio commentary. Conducted around the time of the release of The Jazz Singer (1980), which Fleischer co-directed, the interview begins with a discussion of the diversity of Flescher’s work and the methods by which he selected projects (‘the selection process is a matter of somebody offering me a job’, Fleischer quips). Turner observes that much of Compulsion is shot elaborately, in a style similar to that which characterised Fleischer’s films noir, whilst the sequences featuring Orson Welles as Jonathan Wilk are shot in a more ‘flat’ and restrained manner; Fleischer suggests that this was simply owing to the fact that Welles’ sequences were shot in a hurry, in ten days, ‘and I didn’t have much time to screw around with a lot of angles’. The interview lasts for approximately 90 minutes. - Richard Fleischer Guardian Interview (1981). Recorded at the NFT, Fleischer is interviewed by Adrian Turner. The interview is presented as an audio recording which accompanies the main feature, in the manner of an audio commentary. Conducted around the time of the release of The Jazz Singer (1980), which Fleischer co-directed, the interview begins with a discussion of the diversity of Flescher’s work and the methods by which he selected projects (‘the selection process is a matter of somebody offering me a job’, Fleischer quips). Turner observes that much of Compulsion is shot elaborately, in a style similar to that which characterised Fleischer’s films noir, whilst the sequences featuring Orson Welles as Jonathan Wilk are shot in a more ‘flat’ and restrained manner; Fleischer suggests that this was simply owing to the fact that Welles’ sequences were shot in a hurry, in ten days, ‘and I didn’t have much time to screw around with a lot of angles’. The interview lasts for approximately 90 minutes.

- Richard Fleischer Guardian Interview (1994) (76:42). This interview was again recorded at the NFT, but in 1994. Shot on videotape, this interview repeats some of the stories told in the earlier interview that’s included on this disc, such as Fleischer’s experience working with Orson Welles on Compulsion.

- Orson Welles in the Courtroom Scene from Compulsion (10:11). Here is an audio recording of Welles’ pivotal scene from the picture, which was released as a recording on a 45 rpm disc.

- Lobby Cards, Posters and Stills Gallery (60 images).

- Original Theatrical Trailer (2:27).

Overall

Fleischer’s film version of Compulsion is certainly a compelling picture, though Bradford Dillman’s performance as Artie Straus is overshadowed by the performances of Stockwell and Welles, and one can’t help but wonder how more interesting the film would have been if McDowall had reprised his role as the other half of the murdering duo. (Incidentally, Stockwell’s role as Judd seemed to find deliberate echoes in his performance as Ben, ‘one suave motherfucker’, in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986).) As noted above, the film has a structure that will be familiar to any Law & Order viewer: the fallout from a crime, followed by an extended courtroom sequence. The film builds towards the appearance of Welles as Jonathan Wilk, and Welles is very good in the part – all sweating brows and humble speech patterns. It’s certainly interesting to compare with Hitchcock’s Rope, the other famous picture based on the Leopold and Loeb case. Fleischer’s film version of Compulsion is certainly a compelling picture, though Bradford Dillman’s performance as Artie Straus is overshadowed by the performances of Stockwell and Welles, and one can’t help but wonder how more interesting the film would have been if McDowall had reprised his role as the other half of the murdering duo. (Incidentally, Stockwell’s role as Judd seemed to find deliberate echoes in his performance as Ben, ‘one suave motherfucker’, in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986).) As noted above, the film has a structure that will be familiar to any Law & Order viewer: the fallout from a crime, followed by an extended courtroom sequence. The film builds towards the appearance of Welles as Jonathan Wilk, and Welles is very good in the part – all sweating brows and humble speech patterns. It’s certainly interesting to compare with Hitchcock’s Rope, the other famous picture based on the Leopold and Loeb case.

Signal One’s presentation of the film is, as we’ve come to expect from them, deeply impressive and supported with some excellent contextual material in the form of the two extended interviews with Fleischer, an who is an often overlooked filmmaker. This is certainly a strongly recommended film, and a highly recommended disc.

References

Hare, William, 2007: Hitchcock and the Methods of Suspense. London: McFarland and Company

Salaman, Linda Bradley, 2007: ‘Screening Evil in History: Rope, Compulsion, Scarface, Richard III’. In: Norden, Martin F (ed), 2007: The Changing Face of Evil in Film and Television. New York: Rodopi: 17-36

|