|

The Film

Underground (Emir Kusturica, 1995)

An extraordinary, epic film that covers a half century of the history of Yugoslavia, from the Second World War to the civil war that took place during the 1990s, Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995) begins and ends with the statement ‘Once upon a time there was a country…’. It’s a phrase that alludes to the conventions of the folk talk form, acting as an index of Kusturica’s carnivalesque approach to the material, whilst also underscoring the fact that the film’s narrative is about a nation state formed after the First World War, occupied during the Second World War and torn apart by the civil war that took place during the 1990s. An extraordinary, epic film that covers a half century of the history of Yugoslavia, from the Second World War to the civil war that took place during the 1990s, Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995) begins and ends with the statement ‘Once upon a time there was a country…’. It’s a phrase that alludes to the conventions of the folk talk form, acting as an index of Kusturica’s carnivalesque approach to the material, whilst also underscoring the fact that the film’s narrative is about a nation state formed after the First World War, occupied during the Second World War and torn apart by the civil war that took place during the 1990s.

The film’s narrative is divided into three parts, each focusing on a different period in the history of Yugoslavia. Part one takes place in 1941-4, and covers the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia; part two takes place in 1961, during the Cold War, when Yugoslavia was a communist nation under the rule of former partisan leader Josip Tito; and part three takes place in 1992, following Tito’s death in 1980 and whilst the country was being torn apart by a civil war.

Part one, ‘The War’, begins in 1941, in Belgrade, as a drunken Marko (Miki Manojllovic) and his ‘brother’ Peter Poppara (Lazar Ristovski), nicknamed ‘Blacky’, leading a procession of musicians, return to Blacky’s home – much to the consternation of Blacky’s disapproving wife Vera (Mirjana Karanovic). Marko’s younger brother Ivan (Slavko Stimac) is the keeper at Belgrade’s zoo, and one morning whilst feeding the animals Ivan hears German planes flying over the city. The city is bombed, and ground troops invade. Blacky leaves home with his gun, with the intention to ‘greet the fucking criminals who’ve come to destroy the city’.

Later, as the citizens clear the rubble under the watchful eye of the German troops who have invaded Belgrade, Blacky meets with Natalija (Mirjana Jokovic), an actress. Natalija tells Blacky that everyone knows that he is part of the underground, trafficking in stolen gold and jewellery. Wanted men, Blacky and Marko hide out in Ivan’s home before finding refuge in a cellar, along with the very pregnant Vera. From there, they sell guns and munition stolen from German supply trains, eventually progressing on to making their own small arms.

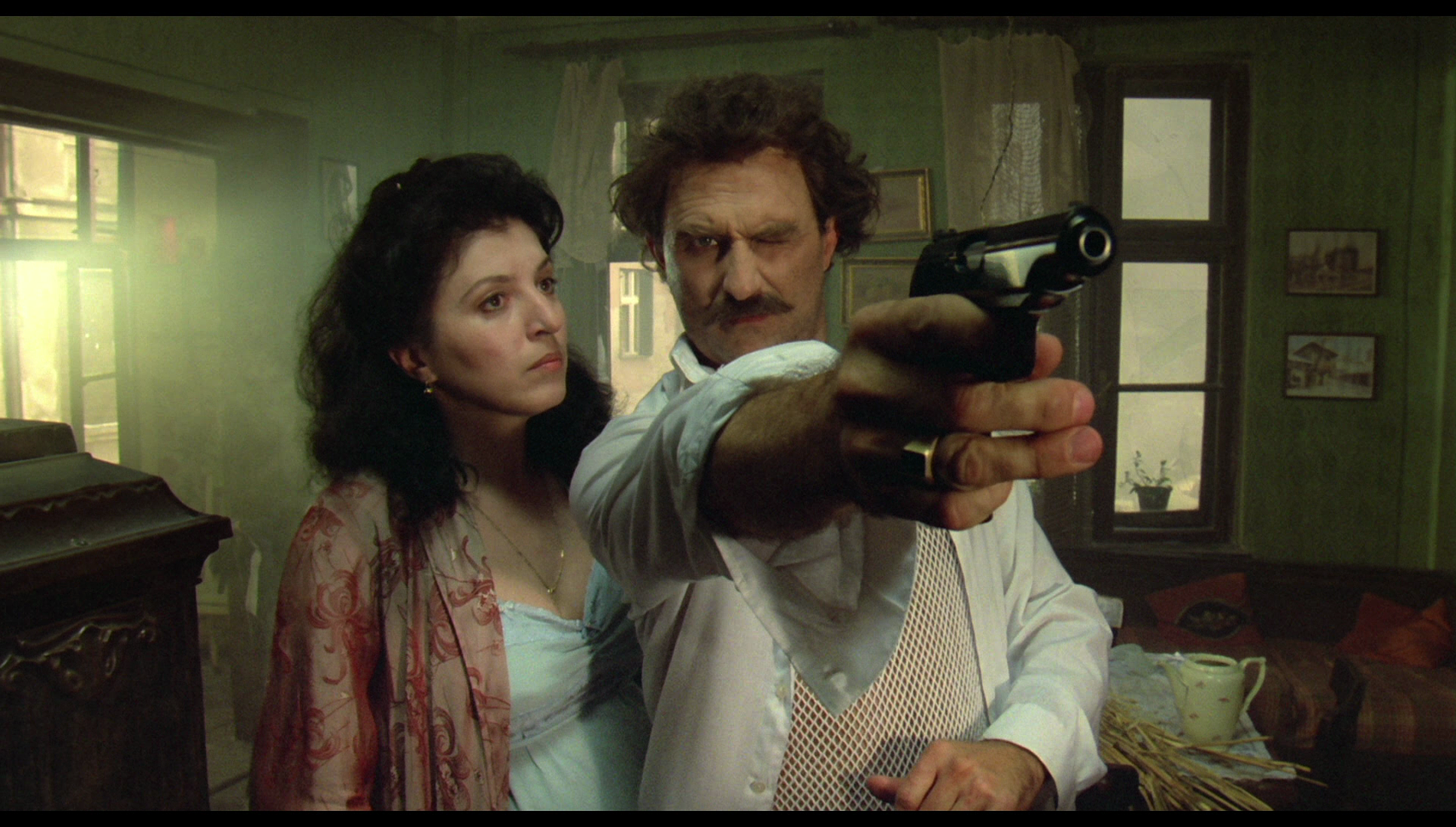

In this underground refuge, Vera gives birth to her and Blacky’s son Jovan, but she dies in childbirth. Three years later, Blacky mourns Vera’s death, and sets his sights on Natalija, who has formed a relationship with Franz (Ernst Stotner), an officer of the occupying German army (‘He kills us and fucks her’, Blacky says). The relationship between Natalija and Franz is mutually beneficial: Franz provides Natalija with care for her invalid brother Bata (Davor Dujmovic), who idolises Blacky. Blacky and Marko inveigle themselves into a theatre in which Natalija is performing in a play. Blacky works his way onto the stage, and the audience believe that his appearance is part of the act. However, Blacky shoots Franz in the chest and abducts Natalija. In this underground refuge, Vera gives birth to her and Blacky’s son Jovan, but she dies in childbirth. Three years later, Blacky mourns Vera’s death, and sets his sights on Natalija, who has formed a relationship with Franz (Ernst Stotner), an officer of the occupying German army (‘He kills us and fucks her’, Blacky says). The relationship between Natalija and Franz is mutually beneficial: Franz provides Natalija with care for her invalid brother Bata (Davor Dujmovic), who idolises Blacky. Blacky and Marko inveigle themselves into a theatre in which Natalija is performing in a play. Blacky works his way onto the stage, and the audience believe that his appearance is part of the act. However, Blacky shoots Franz in the chest and abducts Natalija.

As they celebrate their victory on a boat, Black and Marko are surprised when Franz reveals himself to still be alive, his life having been saved by the bullet proof vest he was wearing, and with a contingent of German soldiers disrupts the proceedings and captures Blacky. Marko escapes on the boat. Blacky is held in a hospital, and tortured with electricity; Marko devises a daring escape plan, infiltrating the hospital and throttling Franz with a stethoscope before fleeing with Blacky and Natalija. They return to the cellar.

Part two, ‘Cold War’, opens in 1961, during the reign of Tito. Marko has become a significant figure in the communist regime, wealthy owing to his trade in small arms manufactured by Blacky and the others who are kept underground, in the cellar, under the illusion that the Second World War is still raging. Now involved in a romantic relationship with Natalija, Marko goes to great lengths to maintain this illusion. Meanwhile, Blacky is believed dead and has attained the status of a martyr for the communist cause, posthumously becoming a People’s Hero – his memory used to prop up the rhetoric of the communist rulers of Yugoslavia. A film is being made about Blacky and Marko’s adventures, with actors who bear a striking resemblance to their real-life counterparts, so much so that Marko struggles to tell them apart.

Marko visits Blacky and the others in the cellar for Jovan’s (Srdjan Todorovic) wedding, in an extended sequence of drink and music. This comes to a head when the orphaned chimp that Ivan rescued from the destroyed zoo loads a shell into a tank that Blacky and his compatriots have made and blows a hole in the wall of the cellar. Blacky and the others escape into the outside world. Blacky and Jovan wander onto the set of the film that is being made about Blacky and Marko’s exploits and Blacky mistakes the actor playing Franz for the real Franz, shooting him. Fugitives, hiding out near a lake, Blacky and Jovan are shot at from a helicopter, which causes Jovan to drown. Marko visits Blacky and the others in the cellar for Jovan’s (Srdjan Todorovic) wedding, in an extended sequence of drink and music. This comes to a head when the orphaned chimp that Ivan rescued from the destroyed zoo loads a shell into a tank that Blacky and his compatriots have made and blows a hole in the wall of the cellar. Blacky and the others escape into the outside world. Blacky and Jovan wander onto the set of the film that is being made about Blacky and Marko’s exploits and Blacky mistakes the actor playing Franz for the real Franz, shooting him. Fugitives, hiding out near a lake, Blacky and Jovan are shot at from a helicopter, which causes Jovan to drown.

The final part of the film, ‘The War’, takes place in 1992, during the civil war which tore Yugoslavia apart. Ivan has been incarcerated in a mental home. Meanwhile, Marko and Natalija are wanted by Interpol. Told that Yugoslavia no longer exists, Ivan feels alone and helpless. He escapes from the hospital and, finding himself yet again in wartorn streets of a city, encounters the now wheelchair-bound Marko and Natalija. Ivan beats Marko to death before hanging himself. Meanwhile, Blacky has become involved in the civil war, searching desperately for Jovan, who he believes to still be alive.

The three time periods in the film are linked by the adventures of the film’s central characters: Communists Marko and Blacky, who following the Axis invasion of their home city of Belgrade become involved in the partisan underground, stealing and then manufacturing small arms for the resistance; Natalija, the object of Marko and Blacky’s affections, who in 1941-4 becomes involved with one of the German officers, Franz; Blacky’s son Jovan, an infant in 1944 whose birth is accompanied by the death of his mother, Blacky’s wife; and Ivan, Belgrade’s zookeeper and Marko’s brother.

Marko and Blacky are depicted as gangsters – an aspect of their characters which is made more pronounced in the longer television edit of the film, also included in this release. They rant against those who steal from them whilst remaining unaware of the irony in the fact that they are themselves thieves (‘We rob stores to steal food and money for our comrades, and these bastards steal from us’, they complain at one point). They work together, the perfect team, until during the final years of the war Natalija comes between them; Marko keeping Blacky in the cellar, under the illusion that the war is still raging, until 1961 in order to profit from Blacky and his comrades’ continued manufacturing of small arms – which Marko sells above ground – and, we may assume, so that he does not have to compete for the affections of Natalija. (‘You put these people down here to live, die and work for you’, Natalija observes.) The pair’s traits complement one another, and as Natalija suggests at one point in the film, ‘The two of you could make one good man’. Marko and Blacky are depicted as gangsters – an aspect of their characters which is made more pronounced in the longer television edit of the film, also included in this release. They rant against those who steal from them whilst remaining unaware of the irony in the fact that they are themselves thieves (‘We rob stores to steal food and money for our comrades, and these bastards steal from us’, they complain at one point). They work together, the perfect team, until during the final years of the war Natalija comes between them; Marko keeping Blacky in the cellar, under the illusion that the war is still raging, until 1961 in order to profit from Blacky and his comrades’ continued manufacturing of small arms – which Marko sells above ground – and, we may assume, so that he does not have to compete for the affections of Natalija. (‘You put these people down here to live, die and work for you’, Natalija observes.) The pair’s traits complement one another, and as Natalija suggests at one point in the film, ‘The two of you could make one good man’.

The title of the film refers to the partisan underground, but also to the underground cellar in which Blacky and the others are held by Marko, under the illusion that the Second World War is still raging above them. The symbolic importance of the cellar and its connection with communism – and for that matter, any other totalising ideology – is made explicit in the final part of the film, when Ivan is held in a mental hospital and two doctors discuss his life in the cellar. ‘Communism was a big cellar’, one of the doctors observes. ‘The whole world is a cellar’, another doctor suggests.

Underground won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1995. The reception that Underground received in the former Yugoslavia was slightly more mixed, however: during the 1980s, Kusturica’s work had been praised in Bosnia-Herzegovina, but during the civil war Kusturica refused to support the Bosnian Muslim government. Kusturica’s decision to shoot Underground in Belgrade, at a time when Serbian forces had encircled and were shelling Sarajevo in a siege of the city that lasted from 1992 to 1996, led to suggestions that Kusturica was allied with the Serbian government and Underground may have even been funded by the Serbians as propaganda. In For Bosnian Muslims, Kusturica’s actions during the shooting of Underground created an ‘image of [the director] as the dupe of the Serbian authorities or as an apologist of some degree’ (Gopnik, cited in Calotychos, 2013: np). Underground won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1995. The reception that Underground received in the former Yugoslavia was slightly more mixed, however: during the 1980s, Kusturica’s work had been praised in Bosnia-Herzegovina, but during the civil war Kusturica refused to support the Bosnian Muslim government. Kusturica’s decision to shoot Underground in Belgrade, at a time when Serbian forces had encircled and were shelling Sarajevo in a siege of the city that lasted from 1992 to 1996, led to suggestions that Kusturica was allied with the Serbian government and Underground may have even been funded by the Serbians as propaganda. In For Bosnian Muslims, Kusturica’s actions during the shooting of Underground created an ‘image of [the director] as the dupe of the Serbian authorities or as an apologist of some degree’ (Gopnik, cited in Calotychos, 2013: np).

Yet other critics accused Kusturica of pandering to Western stereotypes ‘and caving in to a Balkanist self-exoticization’ with was likened to the notion of ‘orientalism’ as outlined in Edward Said’s influential 1978 book (Calotychos, op cit.: np). The characters in Underground are depicted as flamboyant and exotic, with characters who for Iordanova defined the ‘impaired moral standards [perceived as] innate in the Balkan social character’ (Iordanova, quoted in ibid.). Slavoj Zizek grouped Underground with Milche Manchevski’s Before the Rain (1994), arguing that both films represent the ‘ultimate ideological product of Western liberal multiculturalism’, offering ‘to the Western liberal gaze […] precisely what this gaze wants to see in the Balkan war—the spectacle of a timeless, incomprehensible, mythical cycle of passions, in contrast to the decadent and anemic Western life’ (Zizek, quoted in ibid.).

Into this narrative, Kusturica builds a series of repetitions: lines of dialogue echo throughout the script, such as Blacky’s repeated declaration ‘Fucking fascist motherfuckers’, which takes on slightly different connotations every time it appears, and the two scenes in which Blacky ties Natalija to his back – firstly, as they escape from the theatre in which Marko and Blacky believe themselves to have shot and killed Franz, and later as they escape from the cellar in which Marko has kept Blacky confined through deception. These moments of repetition, which accumulate throughout the film, give a suggestion of history repeating itself and of lives that are doomed to be dominated by tyranny. At the end of the 1944 sequence, air raid sirens sound and Natalija asks ‘Who’s bombing us now?’ Marko responds by telling her, ‘The Allies. When it’s not the Germans, the Allies are bombing us’. An intertitle at the end of the sequence tells the audience that in 1944 ‘The Allied bombs destroyed what the Nazis had left of Belgrade’. Into this narrative, Kusturica builds a series of repetitions: lines of dialogue echo throughout the script, such as Blacky’s repeated declaration ‘Fucking fascist motherfuckers’, which takes on slightly different connotations every time it appears, and the two scenes in which Blacky ties Natalija to his back – firstly, as they escape from the theatre in which Marko and Blacky believe themselves to have shot and killed Franz, and later as they escape from the cellar in which Marko has kept Blacky confined through deception. These moments of repetition, which accumulate throughout the film, give a suggestion of history repeating itself and of lives that are doomed to be dominated by tyranny. At the end of the 1944 sequence, air raid sirens sound and Natalija asks ‘Who’s bombing us now?’ Marko responds by telling her, ‘The Allies. When it’s not the Germans, the Allies are bombing us’. An intertitle at the end of the sequence tells the audience that in 1944 ‘The Allied bombs destroyed what the Nazis had left of Belgrade’.

The film foregrounds the artifice of cinema and filmmaking. Blacky, Marko and Natalija are introduced as characters associated with the theatrical tradition, and from the opening sequence of the film Marko and Blacky are followed almost incessantly by the Roma musicians whose instruments blare out the film’s score, composed by Goran Bresovic – in particular, the tracks ‘Mesecina’ and ‘Kalashnikov’, which dominate much of the film’s soundscape. The film itself begins with titles that resemble those of a silent film (‘Once upon a time there was a country, and its capital was Belgrade’, the first of these titles declares) and then a scene depicting a mad, carnivalesque procession headed by a drunken Marko and Blacky, the musicians trailing behind. Throughout the film, notably after the intertitles declaring the transition to each new ‘part’ of the narrative and identifying the time frame (1941/1961/1990s) Kusturica presents the audience with authentic newsreel footage into which his film’s actors have been composited, blurring the lines between historical fact and the fictional world of the narrative but also perhaps intentionally reminding the viewer of the techniques used in vintage propaganda – the changing of the connotations of an image by compositing and/or airbrushing. Furthermore, it’s in a theatre in 1944 that Blacky and Marko stage their rescue of Natalija, as she performs in a play in which Franz is in the audience. Blacky intrudes into this spectacle, masquerading as one of the performers within the play; the audience is unaware of Blacky’s true identity and take his appearance as part of the drama. Blacky commands the other actor onstage to tie Natalija to Blacky’s back, and with Natalija lashed to himself, Blacky approaches the front of the stage and shoots Franz in the chest. Franz appears to die. However, through a coup de theatre later in the film, this is revealed to be a theatrical masquerade: Franz is alive, having been saved from Blacky’s bullets by a bulletproof vest.

The overlap between fictional/theatrical spaces and reality (or rather, the reality presented within the film’s diegesis) is further heightened in the 1961 sequence. Outside the world of the cellar, Marko is shown observing the shooting of an idealised film (‘Spring Comes on a White Horse’) about the escapades of him and Blacky – a film which romanticises their activities as partisans and is intended to consolidate Blacky’s position as a cultural hero (a People’s Hero) of the communist era. The film-within-the-film depicts the events of Underground’s own 1944 sequence hyperbolically: Franz is shown attempting to rape Natalija, whilst in true emulation of Hollywood style, Blacky and Marko mow down German soldiers with machine guns. Marko and Natalija comment on the authenticity of the performances in the film-within-the-film and how much the actors resemble their ‘real’ counterparts (‘Are you me?’, an amazed Marko asks the actor portraying Marko himself). When Blacky and Jovan escape the cellar, thanks to Ivan’s chimp’s intervention, they stumble across the production of ‘Spring Comes on a White Horse’. Mistaking the vehicles transporting the extras dressed as German troops for real troop carriers, they spot the actor playing Franz and believes him to be the real Franz (‘He hasn’t change in years!’, Blacky declares astonishedly, ‘That’s Germans for you’). Likewise, Blacky spots the actor playing himself and mistakes him for another partisan (‘All brave people look like me’, Blacky tells his son). Driven by a desire for revenge, Blacky executes ‘Franz’: he shoots the actor with his rifle. The director of ‘Spring Comes on a White Horse’ seems ecstatic at the versimilitude that has been achieved within the shooting of this scene: presumably unaware that the actor playing Franz has been shot for real, the director yells at Blacky and Jovan to continue their ‘performance’ (‘Don’t break the shot! Go on!’, the director shouts excitedly). The confusion between ‘fiction’ and ‘reality’ is another of the film’s moments of repetition, reminding the film’s viewer of the audience in the theatre and their belief that the appearance of Blacky, in his abduction of Natalija and attempted assassination of Franz, was a part of the play they were watching. The overlap between fictional/theatrical spaces and reality (or rather, the reality presented within the film’s diegesis) is further heightened in the 1961 sequence. Outside the world of the cellar, Marko is shown observing the shooting of an idealised film (‘Spring Comes on a White Horse’) about the escapades of him and Blacky – a film which romanticises their activities as partisans and is intended to consolidate Blacky’s position as a cultural hero (a People’s Hero) of the communist era. The film-within-the-film depicts the events of Underground’s own 1944 sequence hyperbolically: Franz is shown attempting to rape Natalija, whilst in true emulation of Hollywood style, Blacky and Marko mow down German soldiers with machine guns. Marko and Natalija comment on the authenticity of the performances in the film-within-the-film and how much the actors resemble their ‘real’ counterparts (‘Are you me?’, an amazed Marko asks the actor portraying Marko himself). When Blacky and Jovan escape the cellar, thanks to Ivan’s chimp’s intervention, they stumble across the production of ‘Spring Comes on a White Horse’. Mistaking the vehicles transporting the extras dressed as German troops for real troop carriers, they spot the actor playing Franz and believes him to be the real Franz (‘He hasn’t change in years!’, Blacky declares astonishedly, ‘That’s Germans for you’). Likewise, Blacky spots the actor playing himself and mistakes him for another partisan (‘All brave people look like me’, Blacky tells his son). Driven by a desire for revenge, Blacky executes ‘Franz’: he shoots the actor with his rifle. The director of ‘Spring Comes on a White Horse’ seems ecstatic at the versimilitude that has been achieved within the shooting of this scene: presumably unaware that the actor playing Franz has been shot for real, the director yells at Blacky and Jovan to continue their ‘performance’ (‘Don’t break the shot! Go on!’, the director shouts excitedly). The confusion between ‘fiction’ and ‘reality’ is another of the film’s moments of repetition, reminding the film’s viewer of the audience in the theatre and their belief that the appearance of Blacky, in his abduction of Natalija and attempted assassination of Franz, was a part of the play they were watching.

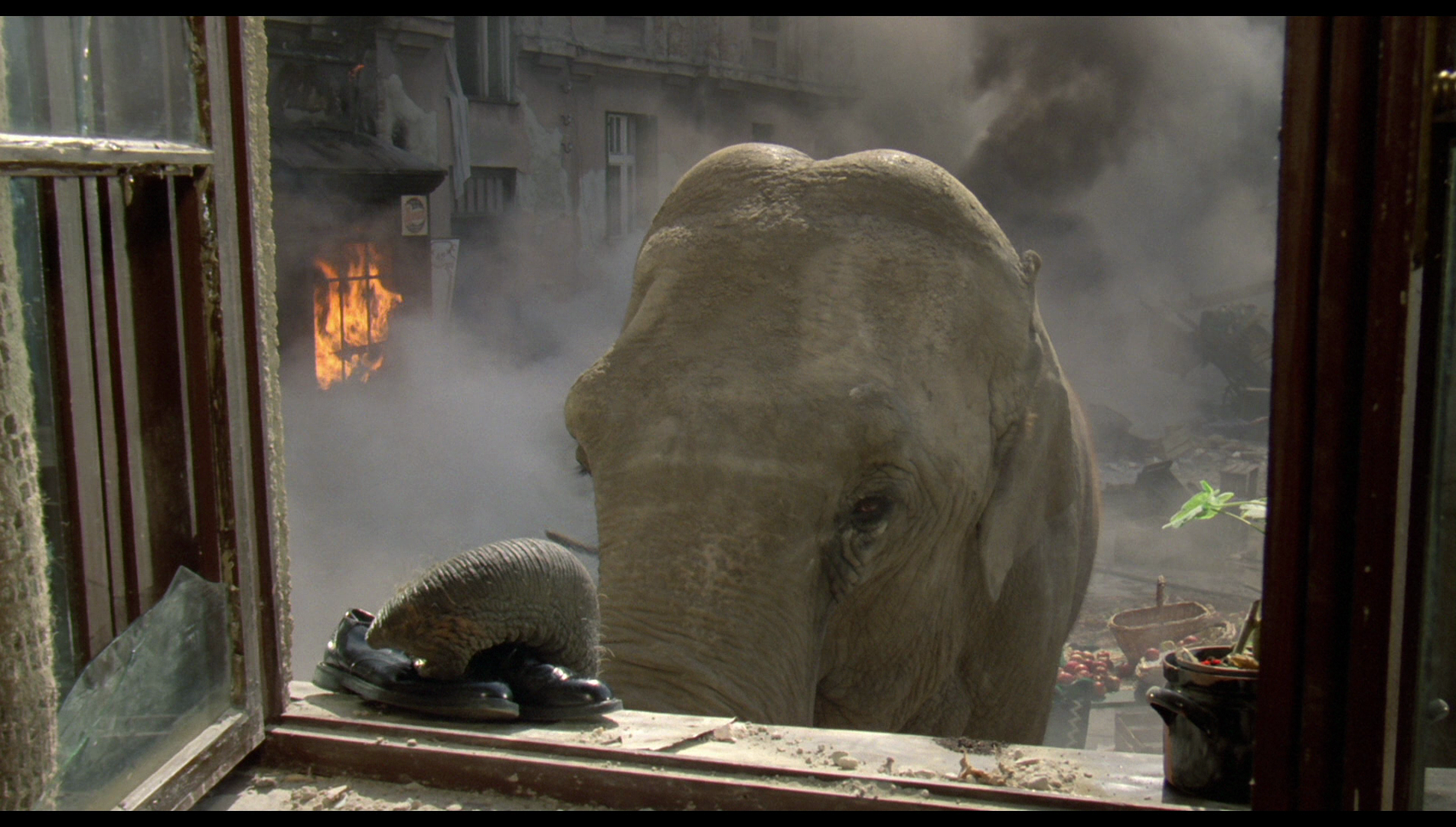

The Axis invasion of Belgrade is depicted in a sequence which begins with the innocent Ivan, his childlike nature emphasised through his stammer, feeding the creatures in the zoo. The German planes fly overhead, dropping their bombs. The creatures are the first victims: some of them (including a tiger, elephant and lion) are freed from their cages by the devastation and dispersed throughout the city, leading to the bizarre spectacle of these creatures wandering through the streets of Belgrade. Other animals are killed, including the mother of a chimpanzee whom Ivan takes under his wing and who accompanies Ivan throughout the film. The harm to the creatures in the zoo, which results in Ivan crying out in agony and dismay, seems to act as a metaphor for the wider devastation wrought by the German bombs. When Blacky and Marko realise they are wanted by the German troops, they seek refuge in Ivan’s home, only to find that the zookeeper has packed his home with animals from the zoo – like Noah and his ark. ‘My bother’s like Noah’, Marko tells Vera, ‘saving the world after the flood’. The Axis invasion of Belgrade is depicted in a sequence which begins with the innocent Ivan, his childlike nature emphasised through his stammer, feeding the creatures in the zoo. The German planes fly overhead, dropping their bombs. The creatures are the first victims: some of them (including a tiger, elephant and lion) are freed from their cages by the devastation and dispersed throughout the city, leading to the bizarre spectacle of these creatures wandering through the streets of Belgrade. Other animals are killed, including the mother of a chimpanzee whom Ivan takes under his wing and who accompanies Ivan throughout the film. The harm to the creatures in the zoo, which results in Ivan crying out in agony and dismay, seems to act as a metaphor for the wider devastation wrought by the German bombs. When Blacky and Marko realise they are wanted by the German troops, they seek refuge in Ivan’s home, only to find that the zookeeper has packed his home with animals from the zoo – like Noah and his ark. ‘My bother’s like Noah’, Marko tells Vera, ‘saving the world after the flood’.

As the film oscillates between sequences of joy and exuberance and other sequences of isolation and despair, the carnivalesque atmosphere is heightened by the group of Roma musicians who appear throughout the film’s more upbeat sequences (and are noticeably absent in the final sequences depicting the civil war) and with whom Blacky and Marko are associated from their introduction. In that introductory sequence, Blacky and Marko are shown returning home from what Mark claims to have been a meeting of fellow Communists, the Roma musicians forming a procession; Blacky and Marko are clearly very, very drunk – as they are through a number of the film’s early sequences. The second part of the film, set in 1961, features an extended sequence in which Marko and Natalija descend into the a lengthy, drunken party in which the music of the Roma musicians blares out and the characters become progressively intoxicated by both drink and one another’s company. This sequence climaxes with Ivan’s chimp climbing into the tank that Blacky and his compatriots have built, loading a shell into its turret gun and firing it, shattering the walls of the cellar and with them, the illusion that Marko has sustained for Blacky and the others who live underground with him – that the Second World War is still raging, and Yugoslavia is still occupied by Axis forces. This event causes Blacky and Jovan, and Ivan and his chimp to escape into the night. The spirit of the carnival dominates the film, including the sequence in which Blacky is tortured with electricity – his hair standing up comically, and his ability to resist the torture explained through his previous occupation as an ‘electrician, a pole climber’ (in Marko’s words). The hospital is populated by mentally disturbed patients – perhaps victims of shell-shock – and as they escape with Blacky Natalija declares that ‘Those crazy people are so sad’. ‘We’re all crazy, Natalija’, Marko reminds her, ‘We just haven’t been diagnosed yet’.

Video

Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1, Underground is here presented in 1080p using the AVC codec and with a running time of 169:48 mins. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1, Underground is here presented in 1080p using the AVC codec and with a running time of 169:48 mins.

Contrast is excellent, and this is evident from the opening sequences featuring the night-time procession headed by Blacky and Marko. The image is wonderfully rich and detailed and retains the structure of 35mm film. There’s some softness here and there, but this seems to be the product of the original photography and is perhaps a feature of the lenses used to shoot the film. The quality of the encode is reflected in the many sequences which feature diffuse light (often achieved through smoke on the set), which look rich in texture without artifacting. It’s a film about performance and masquerade, and to this end the photography juxtaposes earthy tones with vivid primary colours (Natalija’s red dress, for example), and the impressive colour consistency in this presentation foregrounds this aspect of the film’s aesthetic in a manner that is more pronounced than in previous home video releases.

This release also includes the television edit of the feature, running almost six hours across six episodes and carrying the title Once Upon a Time There Was a Country. Included in SD, this edit expands upon the narrative of the film, using the broader canvas of television to bring increased focus on Marko and Blacky’s activities as gangsters, in particular.

In sum, it’s an impressive presentation of the film, a big improvement over the previously available DVD releases of this title.

Audio

Audio is presented via (1) a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track, and (2) a LPCM 2.0 mono track, both in the film’s original language (Croatian). Track (1) is more swollen and emphatic, and track (2) seems more natural and organic. However, both tracks are ‘clean’ and audible throughout, and feature an impressive sense of depth and range. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

DISC ONE (Blu-ray): DISC ONE (Blu-ray):

* The film (169:48)

Trailer (1:07)

DISC TWO (DVD):

Once Upon a Time There Was a Country (television edit):

Episode One (52:11)

Episode Two (52:47)

Episode Three (52:34)

Episode Four (52:44)

DISC THREE (DVD):

Once Upon a Time There Was a Country (television edit):

Episode Five (53:08)

Episode Six (51:06)

- Shooting Days (72:40). This documentary about the production of the film features plenty of behind-the-scenes footage and offers much insight into Kusturica’s method and the themes of the film. The documentary is presented in Croation, with optional English subtitles.

- EPK items (16:21). These electronic press kit snippets include footage of Kusturica directing the film, interviews with Kusturica, Ristovski, Manojlovic and Kljakovic and ‘B-roll’ footage of Jovan’s wedding sequence.

Also included in the release is one of the BFI’s superb booklets with writing about the film by Dina Iordanova, Sean Homer and Michael Brooke.

Overall

Underground is still a deeply divisive film, and some viewers are likely to be alienated by some of the aspects of the picture that led critics at the time of the film to label it as Serbian propaganda. Nevertheless, there’s a strong sense of humanity at the heart of the film, and its most poignant lines are perhaps the dying words of Marko to Natalija: after being beaten by his brother Ivan, Marko observes that ‘No war is a war until a brother kills his brother’. Similarly, at the end of the film, Blacky has shucked off any pretence of being associated with an ideology. Searching desperately for Jovan among the battlefields of Yugoslavia during the civil war, he encounters another soldier – seemingly a mercenary. Blacky addresses this other soldier as ‘comrade’. ‘I’m no “comrade”, sir’, the soldier tells Blacky. ‘And I’m no “sir”, comrade’, Blacky asserts. ‘Why army are you in?’, the soldier asks. ‘My own’, Blacky replies. Underground is still a deeply divisive film, and some viewers are likely to be alienated by some of the aspects of the picture that led critics at the time of the film to label it as Serbian propaganda. Nevertheless, there’s a strong sense of humanity at the heart of the film, and its most poignant lines are perhaps the dying words of Marko to Natalija: after being beaten by his brother Ivan, Marko observes that ‘No war is a war until a brother kills his brother’. Similarly, at the end of the film, Blacky has shucked off any pretence of being associated with an ideology. Searching desperately for Jovan among the battlefields of Yugoslavia during the civil war, he encounters another soldier – seemingly a mercenary. Blacky addresses this other soldier as ‘comrade’. ‘I’m no “comrade”, sir’, the soldier tells Blacky. ‘And I’m no “sir”, comrade’, Blacky asserts. ‘Why army are you in?’, the soldier asks. ‘My own’, Blacky replies.

Regardless of one’s feelings about the film, the BFI’s new Blu-ray release of Underground contains a very strong presentation of the main feature, and the inclusion of the television edit is a superb ‘extra’ feature, ensuring that for fans of the film this release is a hugely impressive upgrade over Underground’s previous DVD releases.

References:

Calotychos, Vangelis, 2013: The Balkan Prospect: Identity, Culture, and Politics in Greece After 1989. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Murtic, Dino, 2015: Post-Yugoslav Cinema: Towards a Cosmopolitan Imagining. London: Palgrave Macmillan

|