|

The Film

Death Walks Twice: Two Films by Luciano Ercoli

The thrilling all’italiana (or giallo all’italiana; ‘Italian-style thriller’) is a remarkably diverse subgenre or ‘style’. This is despite the manner in which, in the video age at least, the Italian thrilling has come to be defined in the eyes of its fans by the thrillers of Mario Bava and, latterly, Dario Argento; these are mysteries structured like Agatha Christie’s whodunits, with a heady dose of brutality and a subtle (or not so subtle, depending on the film) spattering of supernatural motifs, and certain ostensibly fixed visual paradigms (the black-gloved and black clad killer). This perception of the thrilling all’italiana was arguably consolidated, if not created, within Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace) in 1964, and further cemented in Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage) five years later, in 1969. However, despite thrilling pictures of the Bava/Argento style being the most identifiable examples of the Italian-style thriller, at least in English-speaking circles, they are but the tip of the proverbial iceberg, and in truth the Italian thrilling encompasses a broad spectrum of narrative ‘types’: the thrilling all’italiana includes paranoid political thrillers (such as Aldo Lado’s La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Luciano Ercoli’s Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films). Truly, the lack of a fixed narrative paradigm (inner form) and a very slippery set of visual signifiers (outer form) suggests that like the American film noir, the Italian thrilling is best considered a ‘style’ rather than a (sub)genre – the ‘Italian-style’ of the designator applied to the films by Italian critics and audiences (thrilling/giallo all’italiana). The thrilling all’italiana (or giallo all’italiana; ‘Italian-style thriller’) is a remarkably diverse subgenre or ‘style’. This is despite the manner in which, in the video age at least, the Italian thrilling has come to be defined in the eyes of its fans by the thrillers of Mario Bava and, latterly, Dario Argento; these are mysteries structured like Agatha Christie’s whodunits, with a heady dose of brutality and a subtle (or not so subtle, depending on the film) spattering of supernatural motifs, and certain ostensibly fixed visual paradigms (the black-gloved and black clad killer). This perception of the thrilling all’italiana was arguably consolidated, if not created, within Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace) in 1964, and further cemented in Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage) five years later, in 1969. However, despite thrilling pictures of the Bava/Argento style being the most identifiable examples of the Italian-style thriller, at least in English-speaking circles, they are but the tip of the proverbial iceberg, and in truth the Italian thrilling encompasses a broad spectrum of narrative ‘types’: the thrilling all’italiana includes paranoid political thrillers (such as Aldo Lado’s La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Luciano Ercoli’s Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films). Truly, the lack of a fixed narrative paradigm (inner form) and a very slippery set of visual signifiers (outer form) suggests that like the American film noir, the Italian thrilling is best considered a ‘style’ rather than a (sub)genre – the ‘Italian-style’ of the designator applied to the films by Italian critics and audiences (thrilling/giallo all’italiana).

Both written by Ernesto Gastaldi, the two examples of the thrilling all’italiana included in Arrow’s new boxed set – La morte accarezza a mezzanotte (Death Walks at Midnight, 1972) and La morte cammina con i tacchi alti (Death Walks on High Heels, 1971) – were directed by Luciano Ercoli and also feature overlap in terms of their casting, particularly in the starring role given in both features to Ercoli’s wife, the actress Nieves Navarro (acting under her more commonly known Anglicised pseudonym ‘Susan Scott’). They fit snugly into the ‘woman-in-peril’ narrative model with which both Ercoli and Gastaldi have been associated, and which has forerunners in American films noir in terms of pictures such as Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door (1947), Julie (Andrew L Stone, 1956), The House on Telegraph Hill (Robert Wise, 1951) and The Dark Corner (Henry Hathaway, 1946). These are films which, like a number of Ercoli’s examples of the thrilling all’italiana (including the two films in this boxed set), focus on women who find themselves threatened, often in domestic settings, and whose persecution leads them to being perceived as paranoid and hysterical – by both the men in the film and, potentially, the film’s audience itself. These women are frequently shown to be in relationships with men who are either explicitly trying to kill them (in the manner of Bluebeard) or who seem to be manipulating events in order to use the women as patsies in a much grander scheme. In the 1970s, this narrative mode would arguably culminate in Richard Brooks’ 1977 picture Looking for Mr Goodbar, an adaptation of Judith Rossner’s 1975 novel of the same title.

The woman-in-peril form is often cited as having its roots in Ann Radcliffe’s archetypal Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), in which the protagonist Emily St Aubert is forced to live with her aunt, Madame Cheron. Madame Cheron’s husband, Montoni, tries to force Emily to marry his friend, Count Morano. Moving his wife and Emily to his castle of Udolpho, Montoni attempts to railroad Madame Cheron into making him, instead of Emily, her sole heir; when Madame Cheron dies owing to a grave illness and Emily inherits her aunt’s wealth, Emily finds herself the object of a series of frightening events that take place within the castle of Udolpho. Radcliffe’s novel is the model for many subsequent woman-in-peril narratives, from novels like Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) and plays such as Patrick Hamilton’s Gas Light (1938) to thrilling all’italiana pictures like the two Luciano Ercoli films included in this boxed set. Like the woman-in-peril films noir, perhaps owing to its roots in one of the defining Gothic novels, the woman-in-peril thrilling all’italiana often has Gothic overtones and a strong Freudian framework – including a focus on dreams and dreamlike imagery. The woman-in-peril form is often cited as having its roots in Ann Radcliffe’s archetypal Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), in which the protagonist Emily St Aubert is forced to live with her aunt, Madame Cheron. Madame Cheron’s husband, Montoni, tries to force Emily to marry his friend, Count Morano. Moving his wife and Emily to his castle of Udolpho, Montoni attempts to railroad Madame Cheron into making him, instead of Emily, her sole heir; when Madame Cheron dies owing to a grave illness and Emily inherits her aunt’s wealth, Emily finds herself the object of a series of frightening events that take place within the castle of Udolpho. Radcliffe’s novel is the model for many subsequent woman-in-peril narratives, from novels like Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) and plays such as Patrick Hamilton’s Gas Light (1938) to thrilling all’italiana pictures like the two Luciano Ercoli films included in this boxed set. Like the woman-in-peril films noir, perhaps owing to its roots in one of the defining Gothic novels, the woman-in-peril thrilling all’italiana often has Gothic overtones and a strong Freudian framework – including a focus on dreams and dreamlike imagery.

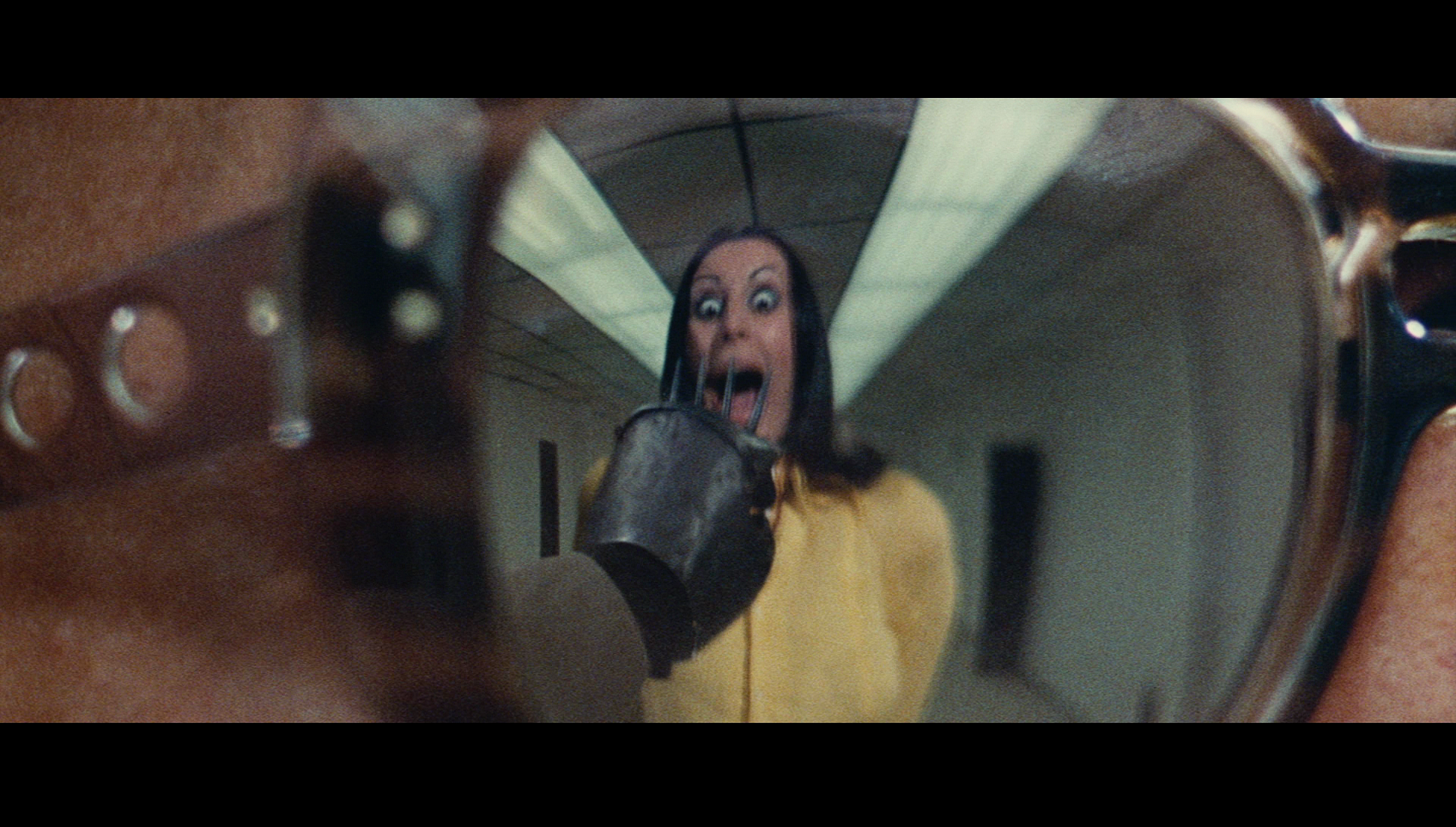

This manifests itself in Death Walks at Midnight in the form of a ‘vision’ that the film’s protagonist, Valentina (Susan Scott), has whilst under the influence of an experimental hallucinogen in the film’s opening sequence. To some extent reflecting the life of the actress playing the role, Valentina works as a fashion model (Scott began her career working as a model in the worlds of fashion and advertising, before becoming an actress). The hallucinogen, HDS, is administered to her in the presence of a journalist, Gio (Simon Andreu). During her ‘trip’, Valentina experiences the frightening vision of a pretty brunette being beaten to death by a man wielding a spiked metal glove. Gio photographs the experiment; Valentina is supposed to wear a mask to obscure her identity, and when she removes it Gio continues to take photographs. Later, the photographs appear on the front page of the gossip magazine Novella 2000, leading Valentina to fall out with Gio.

Valentina attempts a reconciliation with her estranged lover Stefano (Pietro Martellanza, acting under the name ‘Peter Martell’). Stefano is an artist, making bizarre sculptures which involve chiseling round holes in large pieces of wood. Visiting the apartment in the building across from hers, where she believes the murder she ‘witnessed’ to have taken place, Valentina finds herself in danger from the man in her vision; she is saved from him by Stefano.

Valentina is told by a police inspector, Serino (Carlo Gentili), that six months earlier, a murder took place in the apartment directly opposite Valentina’s. The victim was Helene, who the police believe to have been a drug dealer; the presumed perpetrator is Nicola Radelli, one of Helene’s customers, who is currently being held in an insane asylum. Valentina is soon approached by Verushka Wuttenberg (Claudie Lange), the sister of Helene. Verushka takes Valentina to the asylum in which Nicola is being held. However, Valentina recognises neither Nicola nor Helene, whose image is presented to Valentina via photographs kept by Verushka. When Verushka flees, Valentina is left to make her own way back to the city. En route, Valentina sees a hearse carrying the body of Dolores Jachio. Seeing a newspaper article about Dolores, who the article claims committed suicide by laying her head on railway track in front of an oncoming train, Valentina recognises Dolores immediately as the girl in her ‘vision’. Valentina is told by a police inspector, Serino (Carlo Gentili), that six months earlier, a murder took place in the apartment directly opposite Valentina’s. The victim was Helene, who the police believe to have been a drug dealer; the presumed perpetrator is Nicola Radelli, one of Helene’s customers, who is currently being held in an insane asylum. Valentina is soon approached by Verushka Wuttenberg (Claudie Lange), the sister of Helene. Verushka takes Valentina to the asylum in which Nicola is being held. However, Valentina recognises neither Nicola nor Helene, whose image is presented to Valentina via photographs kept by Verushka. When Verushka flees, Valentina is left to make her own way back to the city. En route, Valentina sees a hearse carrying the body of Dolores Jachio. Seeing a newspaper article about Dolores, who the article claims committed suicide by laying her head on railway track in front of an oncoming train, Valentina recognises Dolores immediately as the girl in her ‘vision’.

Whilst photographing and measuring a grave for which Stefano has been commissioned to provide a funerary ornament, Valentina encounters Professor Otto Wuttenberg, the husband of Verushka. Otto warns Valentina not to trust Verushka. Shortly afterwards, Verushka presents herself to Valentina and takes Valentina to the villa of Dolores Jachio, where Valentina spots a photograph in which she recognises the killer she saw in her ‘vision’: it’s Henri Verlaq (Claudio Pellegrini), Helene’s manager. With the plot thickening, Valentina realises that the core of the murder plot and the conspiracy to discredit her lies much closer to home than she might have imagined.

Death Walks on High Heels opens in Paris and features Susan Scott playing Nicole Rochard, a striptease artiste and the daughter of a thief who, in the film’s opening sequence, is shown to be murdered in a sleeper compartment on a train by a masked man with bright blue eyes. Nicole’s father, it seems, was in possession of a significant haul of stolen diamonds, and the police believe that these diamonds are now in the possession of Nicole. Nicole protests her innocence and her estrangement from her criminal father, but to little avail. Early in the film, the police warn Nicole that she is in danger from those who might wish to claim the diamonds for themselves.

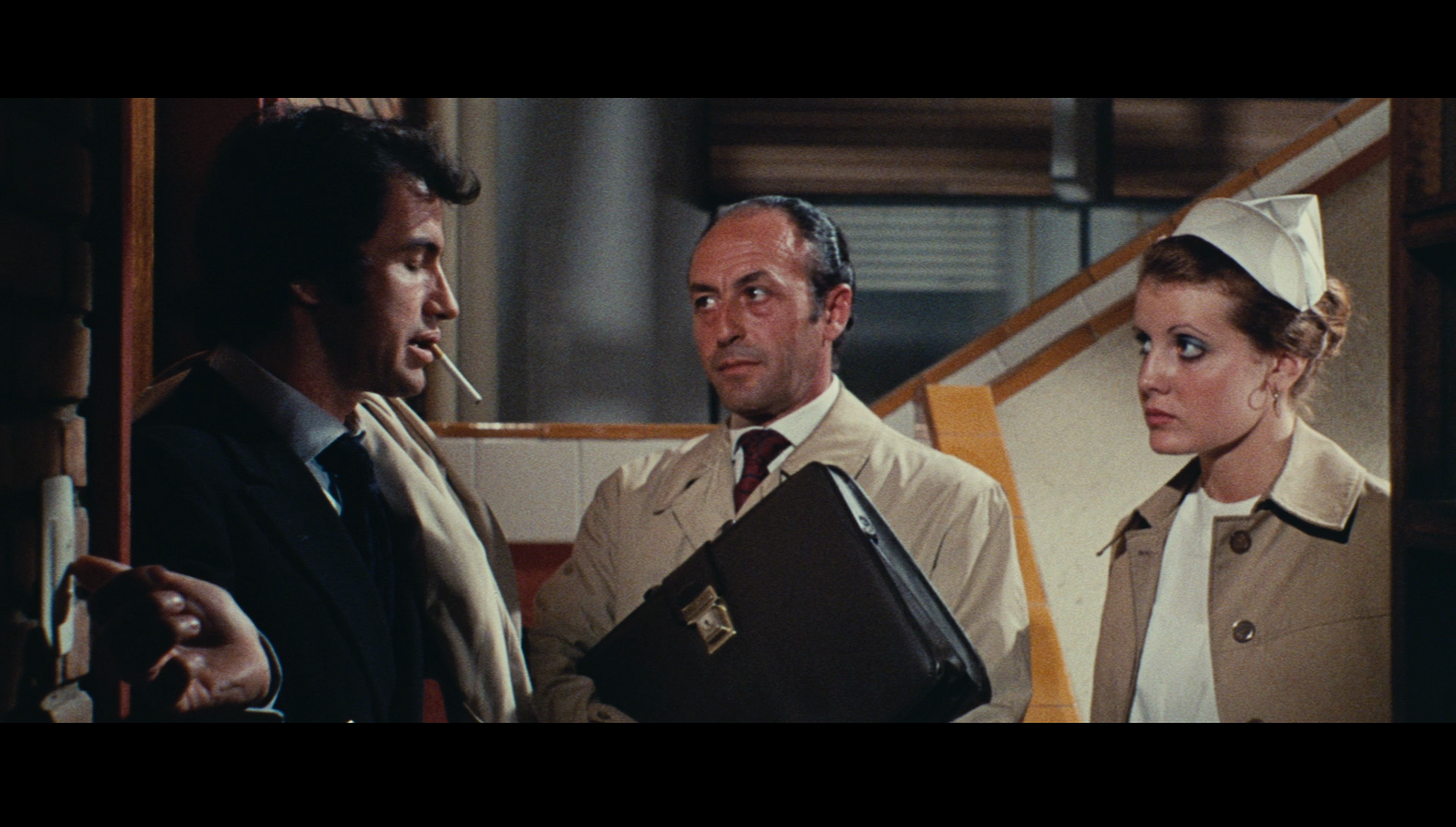

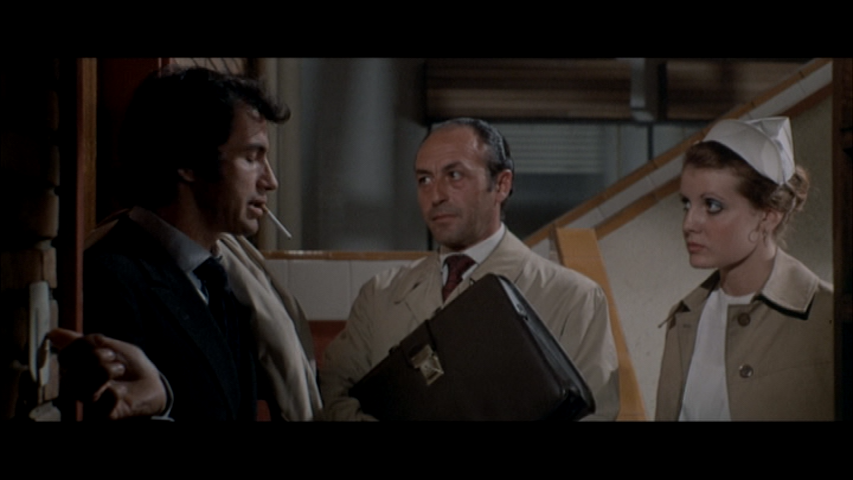

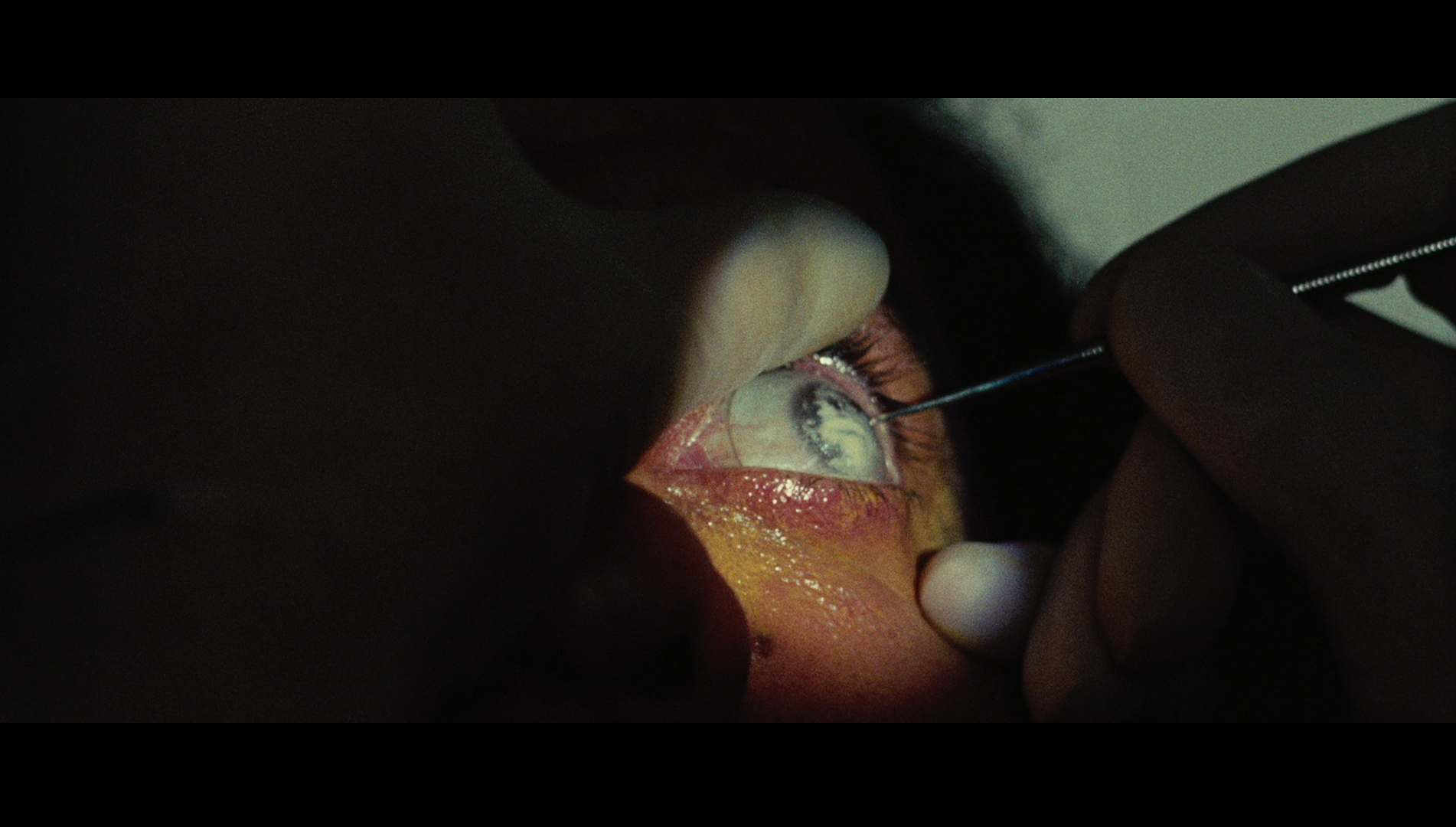

Nicole soon finds herself to be the target of threatening telephone calls; the identity of the caller is obscured by a robotic-sounding electrolarynx. Nicole lives with her wastrel of a boyfriend, Michel Aumont (Simon Andreu). However, at work, after her striptease performances, she is repeatedly pestered by an Englishman, Robert Matthews (Frank Wolff), who is a doctor. After she is attacked in her home by a razor-wielding man in a mask – with the same piercing blue eyes as her father’s killer – Nicole approaches Matthews and asks him to help her flee Paris. Matthews transfers Nicole to his coastal cottage in England, offering her sanctuary there and keeping her as his mistress: Matthews claims to be unable to divorce his wife Vanessa (Claudie Lange), to whose financing he owes his career as a specialist in opthalmology. In the local village, Nicole also meets Captain Lenny (George Rigaud), from whom Matthews is in the process of buying a boat, and the strange Hallory (Luciano Rossi), who takes care of Matthews’ cottage in his absence. Nicole soon finds herself to be the target of threatening telephone calls; the identity of the caller is obscured by a robotic-sounding electrolarynx. Nicole lives with her wastrel of a boyfriend, Michel Aumont (Simon Andreu). However, at work, after her striptease performances, she is repeatedly pestered by an Englishman, Robert Matthews (Frank Wolff), who is a doctor. After she is attacked in her home by a razor-wielding man in a mask – with the same piercing blue eyes as her father’s killer – Nicole approaches Matthews and asks him to help her flee Paris. Matthews transfers Nicole to his coastal cottage in England, offering her sanctuary there and keeping her as his mistress: Matthews claims to be unable to divorce his wife Vanessa (Claudie Lange), to whose financing he owes his career as a specialist in opthalmology. In the local village, Nicole also meets Captain Lenny (George Rigaud), from whom Matthews is in the process of buying a boat, and the strange Hallory (Luciano Rossi), who takes care of Matthews’ cottage in his absence.

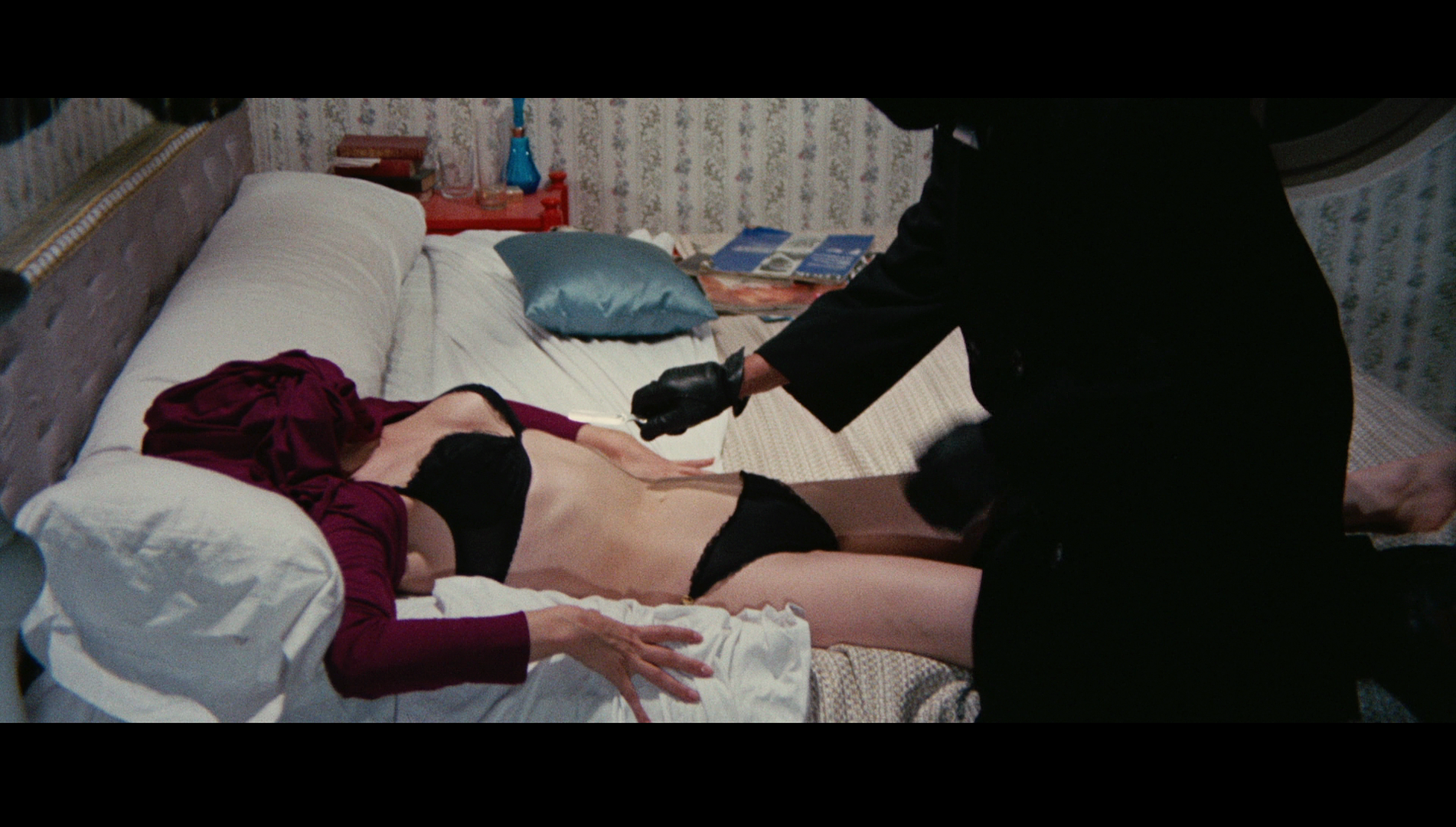

One night, whilst Matthews is away, Nicole receives a mysterious visitor who passes to her a large sum of money. The next day, Nicole has disappeared, and Matthews is shot in his surgery by an assailant wearing women’s boots, similar to those worn by Nicole. The only witness to this crime is Smith (J Manuel Martin), a blind man who is one of Matthews’ patients. Matthews survives but is unable to identify his attacker. Nicole’s body turns up in the net of a fishing vessel, eliminating her as a suspect in the shooting of Matthews. Michel arrives in the village, angered at the death of Nicole. Butting heads with the detectives in charge of the investigation, Inspector Baxter (Carlo Gentili) and Bergson (Fabrizio Moresco), Michel decides to conduct his own investigation into his lover’s demise. However, when it is revealed that Michel is in the possession of a pair of blue contact lenses, his role in Nicole’s persecution and death seems to become much more complicated.

Death Walks on High Heels contains a strong focus on gender and an overt inversion of gender roles. The film’s opening sequences go to great lengths to foreground the ways in which Michel is ‘kept’ by Nicole’s work as a striptease artiste and thus labeled as a ‘pimp’. When Michel complains that he and Nicole seem to ‘make out only between shows’, Nicole responds by telling him dryly, ‘Listen, darling. Someone has to work to keep things going while you wait to be offered a position as an ambassador’. In the midst of a drunken argument, Michel lashes out at Nicole, suggesting that she gets her kicks from the knowledge that during her dances, she’s exciting the members of her audience sexually: ‘You wiggle your ass around to bring in the money, and drink it all to your health’, he says before underscoring how his status as a ‘kept’ man is a sleight against his masculinity, ‘You’re a beautiful woman, Nicole, but I can manage without you, your money or your ass. I’m fed up with being scorned by these people. They say, “Look, it’s Nicole’s pimp”’. This relationship finds its opposite later in the film, when Nicole is ‘kept’ by Robert Matthews, who buys her fine clothes before transferring her to an isolated coastal cottage in England. Death Walks on High Heels contains a strong focus on gender and an overt inversion of gender roles. The film’s opening sequences go to great lengths to foreground the ways in which Michel is ‘kept’ by Nicole’s work as a striptease artiste and thus labeled as a ‘pimp’. When Michel complains that he and Nicole seem to ‘make out only between shows’, Nicole responds by telling him dryly, ‘Listen, darling. Someone has to work to keep things going while you wait to be offered a position as an ambassador’. In the midst of a drunken argument, Michel lashes out at Nicole, suggesting that she gets her kicks from the knowledge that during her dances, she’s exciting the members of her audience sexually: ‘You wiggle your ass around to bring in the money, and drink it all to your health’, he says before underscoring how his status as a ‘kept’ man is a sleight against his masculinity, ‘You’re a beautiful woman, Nicole, but I can manage without you, your money or your ass. I’m fed up with being scorned by these people. They say, “Look, it’s Nicole’s pimp”’. This relationship finds its opposite later in the film, when Nicole is ‘kept’ by Robert Matthews, who buys her fine clothes before transferring her to an isolated coastal cottage in England.

The film’s inversion of gender roles takes place on other levels too. Susan’s dialogue in the first part of the picture is often subtly ‘macho’: ‘Stop breaking my balls’, she commands the nuisance telephone caller when he demands that he ‘must see you privately’. Much later, towards the film’s climax, Michel and Inspector Baxter break into Matthews’ cottage following the death of Nicole and finds Hallory dressed in Nicole’s underwear and dancing: ‘It’s a vice, Inspector’, Hallory protests weakly, ‘It’s a vice’. Hallory’s peculiar ‘vice’, of course, connects him with the suspect in the shooting of Matthews, who the (ostensibly) blind Smith asserts, based on the sound of the assailant’s footsteps, was either ‘a man wearing a woman’s shoes’ or ‘just a very determined woman’.

The English village setting of Death Walks on High Heels ensures that this film falls into a fairly small category of examples of the thrilling all’italiana that take place in rural England – alongside films such as Michele Lupo’s Concerto per pistola solista (The Weekend Murders, 1970). Along with the presence of a man with a military title (Captain Lenny), the village pub – a hotbed of village gossip into which Nicole saunters – might remind the film’s viewers of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), an adaptation of Gordon Williams’ 1969 novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. (‘The village is too small to hide certain things’, Matthews observes at one point, ‘And people like to gossip, which is worse’.) The English, it seems, are repressed and prudish: Matthews involves Nicole in a masquerade, pretending that she is his wife in an attempt to avoid the malicious gossip of the locals. Matthews tells Nicole that ‘nothing ever happens around this village. You know, they still think the tango is a sinful dance’. The repression of the English is only skin deep, however: for example, the silent, watchful Hallory is revealed to be a transvestite who secretly dresses in Nicole’s underwear and dances for an imagined audience. (Matthews introduces Hallory by saying to Nicole, ‘He makes a bad impression, but he’s all right. He’s reliable’.) This is contrasted with Paris, where Nicole works as a stripper in venues that are packed with audience members, and Matthews is able to use an 8mm camera to openly record one of Nicole’s performances. The contrast between the sexual freedom of Europe and the repression of the English comes to a head in a scene in which Nicole seduces Matthews: echoing the staging and symbolism of the chess sequence from Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), during a meal in front of a raging fire in Matthew’s coastal cottage, Nicole eats with her fingers, sloppily ‘fellating’ the fish that Matthews has presented her with before unrolling a napkin in a manner that can be mistaken for nothing other than an overt allusion to the manual stimulation of the male member. (Tension between England and the continent is also foregrounded when Michel arrives in the village following the death of Nicole and asserts ‘That English bastard killed her’. Bergons responds to Michel’s declaration by querying, ‘Which one? There are fifty million of us on this island’.) The English village setting of Death Walks on High Heels ensures that this film falls into a fairly small category of examples of the thrilling all’italiana that take place in rural England – alongside films such as Michele Lupo’s Concerto per pistola solista (The Weekend Murders, 1970). Along with the presence of a man with a military title (Captain Lenny), the village pub – a hotbed of village gossip into which Nicole saunters – might remind the film’s viewers of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), an adaptation of Gordon Williams’ 1969 novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. (‘The village is too small to hide certain things’, Matthews observes at one point, ‘And people like to gossip, which is worse’.) The English, it seems, are repressed and prudish: Matthews involves Nicole in a masquerade, pretending that she is his wife in an attempt to avoid the malicious gossip of the locals. Matthews tells Nicole that ‘nothing ever happens around this village. You know, they still think the tango is a sinful dance’. The repression of the English is only skin deep, however: for example, the silent, watchful Hallory is revealed to be a transvestite who secretly dresses in Nicole’s underwear and dances for an imagined audience. (Matthews introduces Hallory by saying to Nicole, ‘He makes a bad impression, but he’s all right. He’s reliable’.) This is contrasted with Paris, where Nicole works as a stripper in venues that are packed with audience members, and Matthews is able to use an 8mm camera to openly record one of Nicole’s performances. The contrast between the sexual freedom of Europe and the repression of the English comes to a head in a scene in which Nicole seduces Matthews: echoing the staging and symbolism of the chess sequence from Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), during a meal in front of a raging fire in Matthew’s coastal cottage, Nicole eats with her fingers, sloppily ‘fellating’ the fish that Matthews has presented her with before unrolling a napkin in a manner that can be mistaken for nothing other than an overt allusion to the manual stimulation of the male member. (Tension between England and the continent is also foregrounded when Michel arrives in the village following the death of Nicole and asserts ‘That English bastard killed her’. Bergons responds to Michel’s declaration by querying, ‘Which one? There are fifty million of us on this island’.)

Death Walks on High Heels seems to be a film about liminality: even in Paris, Nicole lives a life of ‘inbetweenness’, having to keep her lover Michel whilst working in a profession (stripping) that is, culturally speaking, on the borderline of ‘legitimate’ employment. Nicole is tainted by the knowledge that her father was a criminal, which in the eyes of the police also marks her as a potential criminal. Matthews transplants Nicole from Paris to an English village that is meant to offer her sanctuary and in which she is regarded with suspicion; the strange ‘out-of-placeness’ of this village is reinforced by Nicole’s seeming entrapment within the cottage. She is unable to venture outside, spending her days awaiting Matthews’ return during the evening. Eventually, Nicole comes to realise that whilst superficially idyllic, life in the English village is ultimately stultifying, expressing this in a manner which highlights the symbolic function of the village and Matthews’ cottage as a kind of limbo: she tells Matthews that she can no longer bear to be ‘in this small town which seems like a village of the dead’. Death Walks on High Heels seems to be a film about liminality: even in Paris, Nicole lives a life of ‘inbetweenness’, having to keep her lover Michel whilst working in a profession (stripping) that is, culturally speaking, on the borderline of ‘legitimate’ employment. Nicole is tainted by the knowledge that her father was a criminal, which in the eyes of the police also marks her as a potential criminal. Matthews transplants Nicole from Paris to an English village that is meant to offer her sanctuary and in which she is regarded with suspicion; the strange ‘out-of-placeness’ of this village is reinforced by Nicole’s seeming entrapment within the cottage. She is unable to venture outside, spending her days awaiting Matthews’ return during the evening. Eventually, Nicole comes to realise that whilst superficially idyllic, life in the English village is ultimately stultifying, expressing this in a manner which highlights the symbolic function of the village and Matthews’ cottage as a kind of limbo: she tells Matthews that she can no longer bear to be ‘in this small town which seems like a village of the dead’.

Discussing Ercoli’s work, Danny Shipka suggests that Ercoli’s first feature, Le foto proibite di una signora per bene, defined his cinema as ‘a mixture of detective stories with lots of overt sexuality’ which ‘focused on the deceptive relationships between heterosexual spouses and lovers’ (Shipka, 2011: 93). The films of Ercoli foreground ‘the nightmare of being threatened by one’s own sexual partner’ (ibid.). The films feature ‘strong female characters’ and an abiding theme of ‘[d]eception from men’ (ibid.). Shipka has observed that following the formula established by Ercoli in his directorial debut, Death Walks at Midnight and Death Walks on High Heels both feature Scott ‘as a tough, independent woman who is inevitably deceived by her lovers’, resulting in either ‘sudden death […] or in abusive violence’ (ibid.). Scott’s performances in both pictures ‘imbues the characters [she plays] with a new-found strength that mirrors the attainment of equality for women in the early ‘70s’ (ibid.). Shipka suggests that the ‘strong’ women in Ercoli’s pictures can be traced to the director’s fascination with fumetti which feature ‘stronger women’s leads [than, say, American comics], but these women must go through a myriad of life-changing events’ (ibid.). The women in Ercoli’s films offer a counterpoint to ‘the screaming, unbalanced women’ in the thrilling all’italiana films of Argento and Sergio Martino, for example (ibid.).

In both Death Walks at Midnight and Death Walks on High Heels, Scott plays a character who is a victim of ‘gaslighting’. ‘Gaslighting’ is a term that, it is said, originates in Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gas Light, in which Jack Manningham attempts to convince his wife Bella that she is losing her mind; the term ‘gaslighting’ refers to the phenomenon by which someone may attempt to convince another person, usually a woman, that they are going insane, so that they doubt their perception of events or their memory. In Death Walks at Midnight, Scott’s character Valentina is the victim of a plot that has been put in play by her lover Stefano, but she is also encouraged to doubt her perception by Inspector Serino, who dismisses what Valentina claims to have seen during her ‘trip’ as ‘absurd’. Serino’s apparent refusal to help Valentina results in her frustrated declaration, ‘Fine! We’ll just wait for him [the murderer] to kill me!’ In both Death Walks at Midnight and Death Walks on High Heels, Scott plays a character who is a victim of ‘gaslighting’. ‘Gaslighting’ is a term that, it is said, originates in Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play Gas Light, in which Jack Manningham attempts to convince his wife Bella that she is losing her mind; the term ‘gaslighting’ refers to the phenomenon by which someone may attempt to convince another person, usually a woman, that they are going insane, so that they doubt their perception of events or their memory. In Death Walks at Midnight, Scott’s character Valentina is the victim of a plot that has been put in play by her lover Stefano, but she is also encouraged to doubt her perception by Inspector Serino, who dismisses what Valentina claims to have seen during her ‘trip’ as ‘absurd’. Serino’s apparent refusal to help Valentina results in her frustrated declaration, ‘Fine! We’ll just wait for him [the murderer] to kill me!’

Death Walks at Midnight’s opening sequence, depicting Valentina being subjected to the experimental hallucinogen HDS in the presence of Gio, and the manner in which her ‘trip’ turns into a bad one has some similarities with Roger Corman’s notorious picture about LSD, The Trip (1967). In that film, the protagonist Paul (Peter Fonda), a director of television commercials who is undergoing a messy divorce, experiments with LSD under the watchful eyes of his ‘guru’ (Bruce Dern); Paul’s trip begins well enough but quickly sours into a nightmarish scenario involving Gothic archetypes (an excuse for Corman to reuse some of the sets from his Gothic horror films of the 1960s). Aside from both featuring ‘bad trips’, Death Walks at Midnight and The Trip associate hallucinogens and the experience of having a ‘trip’ with creative professions.

Death Walks on High Heels invites obvious comparisons with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) with, most obviously, the murder of a character who seems to be the film’s protagonist approximately half way through the narrative, and Gastaldi and Ercoli battling to shift audience sympathies amongst their characters. Like Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in Psycho, Nicole takes flight, and she is also believed to be in possession of stolen goods (in Psycho, Marion has the money stolen from her employer; in Death Walks on High Heels, Nicole is believed to be carrying the diamonds stolen by her father). Prior to Nicole’s murder, Death Walks on High Heels shifts audience identification away from her by playing out a key scene from a distance: the scene in which Nicole is approached in the cottage at night by a mysterious figure who hands her a large sum of money is played out for the film’s audience as if watched through the binoculars of a voyeur who has been spying on Nicole. (This voyeur is later revealed to be Captain Lenny.) Once it moves to Robert Matthews’ English coastal cottage, Death Walks on High Heels also seems to nod towards the Edgar Wallace adaptations that were popular in Germany during the 1960s and 1970s, in the form of the two English detectives, Inspector Baxter (Carlo Gentili) and his assistant Bergson (Fabrizio Moresco), who attempt to solve the murder of Nicole. Death Walks on High Heels invites obvious comparisons with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) with, most obviously, the murder of a character who seems to be the film’s protagonist approximately half way through the narrative, and Gastaldi and Ercoli battling to shift audience sympathies amongst their characters. Like Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in Psycho, Nicole takes flight, and she is also believed to be in possession of stolen goods (in Psycho, Marion has the money stolen from her employer; in Death Walks on High Heels, Nicole is believed to be carrying the diamonds stolen by her father). Prior to Nicole’s murder, Death Walks on High Heels shifts audience identification away from her by playing out a key scene from a distance: the scene in which Nicole is approached in the cottage at night by a mysterious figure who hands her a large sum of money is played out for the film’s audience as if watched through the binoculars of a voyeur who has been spying on Nicole. (This voyeur is later revealed to be Captain Lenny.) Once it moves to Robert Matthews’ English coastal cottage, Death Walks on High Heels also seems to nod towards the Edgar Wallace adaptations that were popular in Germany during the 1960s and 1970s, in the form of the two English detectives, Inspector Baxter (Carlo Gentili) and his assistant Bergson (Fabrizio Moresco), who attempt to solve the murder of Nicole.

Structurally, Death Walks at Midnight seems to owe a debt to another Hitchcock film, Rear Window (1954): Valentina’s witnessing of Dolores’ murder (via the ‘vision’ she experiences whilst suffering from the effects of the hallucinogen) precipitates her desire to solve the crime, offering obvious parallels with Jeff’s (James Stewart) investigation of a crime that he witnesses whilst gazing out the window of his apartment. At least superficially, in terms of the ‘vision’ that Valentina experiences whilst under the effect of the experimental hallucinogen, Death Walks at Midnight is connected to the plethora of thrillers and horror pictures made during the 1970s which feature psychic phenomena as an overriding theme. These films included American pictures such as, at the lower end of the spectrum, Psychic Killer (Ray Danton, 1975) and The Premonition (Robert Allen Schnitzer, 1976), and more glossy Hollywood productions like The Reincarnation of Peter Proud (J Lee Thompson, 1976), Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976) and The Fury (De Palma, 1978). Certain other examples of the thrilling all’italiana followed this trend: notable amongst these pictures are Argento’s Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1975), whose narrative begins with the murder of a psychic (Macha Meril); and Lucio Fulci’s Sette note in nero (The Psychic, 1977), another ‘woman-in-peril’ example of the thrilling which features a clairvoyant (Jennifer O’Neill) as its protagonist.

Here, in Death Walks at Midnight, Valentina’s ‘vision’ of what is eventually revealed to be Dolores’ murder at the hands (or rather, spiked glove) of Henri initially seems to be a product of her experimentation with the hallucinogen. However, as the narrative progresses it’s suggested to be a psychic vision of a murder (that of Helene) that was committed several months prior to the events depicted within the film. This is explained by the suggestion that the hallucinogen freed a memory (of Valentina witnessing the murder of Helene, which took place in the apartment opposite) that till that point had been buried deep within Valentina’s subconscious. (Again, this is very ‘of the period’.) Gio suggests to Valentina that ‘You saw the murderer kill that woman six months ago but your subconscious rejected the reality. Self-censorship [….] On HDS, your subconscious relaxed and freed those images’. However, this argument is undermined later in the film, when Valentina can identify neither the victim (Helene) nor the alleged perpetrator when presented with photographs of them, suggesting that her ‘vision’ was something more complex than a suppressed memory. Finally, another explanation is offered: the murder Valentina saw wasn’t that of Helene but rather the murder of Dolores, which Valentina glimpsed through the window of her apartment concurrently with her ‘trip’. Here, in Death Walks at Midnight, Valentina’s ‘vision’ of what is eventually revealed to be Dolores’ murder at the hands (or rather, spiked glove) of Henri initially seems to be a product of her experimentation with the hallucinogen. However, as the narrative progresses it’s suggested to be a psychic vision of a murder (that of Helene) that was committed several months prior to the events depicted within the film. This is explained by the suggestion that the hallucinogen freed a memory (of Valentina witnessing the murder of Helene, which took place in the apartment opposite) that till that point had been buried deep within Valentina’s subconscious. (Again, this is very ‘of the period’.) Gio suggests to Valentina that ‘You saw the murderer kill that woman six months ago but your subconscious rejected the reality. Self-censorship [….] On HDS, your subconscious relaxed and freed those images’. However, this argument is undermined later in the film, when Valentina can identify neither the victim (Helene) nor the alleged perpetrator when presented with photographs of them, suggesting that her ‘vision’ was something more complex than a suppressed memory. Finally, another explanation is offered: the murder Valentina saw wasn’t that of Helene but rather the murder of Dolores, which Valentina glimpsed through the window of her apartment concurrently with her ‘trip’.

Throughout the film, Valentina is regarded with disbelief when she tries to impress upon others the importance of her ‘vision’. Inspector Serino dismisses her claims to have witnessed a murder as ‘absurd’ and absent of facts. Like a number of female characters within examples of the thrilling all’italiana, she is marked as suffering from a form of hysteria. Likewise, Verushka is presented to the audience in ambiguous terms: for much of the film, we are left wondering whether she is unreliable and therefore not to be believed, or that she holds the key to the puzzle. In the cemetery, whilst measuring and photographing the grave for Stefano, Valentina encounters Otto. He warns Valentina not to trust Verushka, claiming that she is ‘very ill’ and that ‘you mustn’t believe her’. On the other hand, Verushka approaches Valentina shortly after Otto has left; Verushka asks Valentina, ‘Don’t you want to know the truth? Only I can help her’. In its depiction of Valentina and Verushka, both of whom are labeled as hysterical and unreliable by the other characters in the picture, Death Walks at Midnight reminds us of how the thrilling all’italiana often frames women as suspicious or deviant: for Valentina, this is explicitly connected to her status as young, free, childless and single when, fearing for her life, she flees to Stefano’s place, and Stefano admonishes her by saying ‘If you had a kid, you wouldn’t waste your life like this. You wouldn’t do so many stupid, useless things’. (Later, a drunken Stefano strikes Valentina and tells her angrily, ‘You’re just like all the others. You don’t even have the guts to be a whore’.)

Nevertheless, the real villains in Death Walks at Midnight, and in Death Walks on High Heels, are the men who engender paranoia within the female protagonists. Death Walks at Midnight deals explicitly with the association between illegal drugs and deviance: the film begins with Valentina allowing the experimental hallucinogen to be administered to her, and Gio’s photographs of the event being splashed across the front page of Novella 2000, making Valentina the most famous drug addict in Milan; and as the narrative progresses, it’s suggested that Helene was a drug dealer, which is perhaps the reason for the police’s lack of interest in her murder. The film returns to the theme of drugs via repeated discussion by the detectives of how rife illegal narcotics are within the city, and finally the conspiracy against Valentina is revealed to involve drugs. Nevertheless, the real villains in Death Walks at Midnight, and in Death Walks on High Heels, are the men who engender paranoia within the female protagonists. Death Walks at Midnight deals explicitly with the association between illegal drugs and deviance: the film begins with Valentina allowing the experimental hallucinogen to be administered to her, and Gio’s photographs of the event being splashed across the front page of Novella 2000, making Valentina the most famous drug addict in Milan; and as the narrative progresses, it’s suggested that Helene was a drug dealer, which is perhaps the reason for the police’s lack of interest in her murder. The film returns to the theme of drugs via repeated discussion by the detectives of how rife illegal narcotics are within the city, and finally the conspiracy against Valentina is revealed to involve drugs.

Valentina’s profession as a model adds little to the film’s plot; the photographs Gio takes of her whilst she is experiencing her hallucinogenic trip appear on the front page of the well-known Italian gossip magazine, Novella 2000. Valentina is displeased with this, causing her to fall out with Gio, who Valentina believes has betrayed her trust. Later, at a party, Valentina refuses a joint that is passed to her by a male partygoer; to this, the young man responds, ‘Why not? You’re the most famous drug user in all of Italy’.

The film satirises the art world subtly: Stefano’s bizarre artwork, which involves large circular holes being chiseled out of pieces of what seem to be driftwood leading to the wood looking like Swiss cheese, is the subject of an exhibition. (It’s tempting to read Stefano’s artwork as a strange metaphor for the plot against Valentina, but to do so may be stretching the point somewhat.) At the exhibition, a middle-aged man and a younger woman are shown contemplating one of Stefano’s ‘sculptures’ carefully. ‘It looks like a slice of Gruyere’, the middle-aged man asserts solemnly. ‘You’re so old-fashioned’, the young woman tells him, angered that her partner has failed to ‘understand’ the sculpture. From this exhibition, Stefano acquires a rather bizarre commission to sculpt a funerary ornament, which leads him to ask Valentina to photograph and measure the grave for which his sculpture will be constructed – during which she meets Otto Wutenberg.

The violence of Death Walks on High Heels is highly sexual: when Nicole is attacked in her apartment, her attacker uses his straight razor to strip her before running the flat edge of the razor against her groin whilst threatening, ‘With this razor you won’t feel the pain straight away, but it will leave your body with horrible scars’. On the other hand, the violence in Death Walks at Midnight is strikingly brutal and directed towards the faces of the women who are codified as victims: in Valentina’s ‘vision’ of Dolores’ murder, she sees Dolores being beaten about the face by Henri, who wields a spiked metal glove. Later, the glove is used again, by another perpetrator, to destroy the face of a woman. The filmmakers almost invite the audience to read these sequences as the forces of patriarchy enacting their revenge upon beautiful women by destroying their faces. Elsewhere, gender roles are subtly displaced: in one sequence, Stefano enters Valentina’s apartment and seats himself on her sofa, his cross-legged pose mirroring that of the feminine doll that sits on the sofa beside him. The representation of male-female relationships, however, is unambiguously cynical. Early in the film, Valentina attempts a reconciliation with Stefano. ‘I should have married you’, Valentina observes. ‘We’d be having an argument about that article’, Stefano responds dryly, referring to the article in Novella 2000 about Valentina’s supposed drug problem. The violence of Death Walks on High Heels is highly sexual: when Nicole is attacked in her apartment, her attacker uses his straight razor to strip her before running the flat edge of the razor against her groin whilst threatening, ‘With this razor you won’t feel the pain straight away, but it will leave your body with horrible scars’. On the other hand, the violence in Death Walks at Midnight is strikingly brutal and directed towards the faces of the women who are codified as victims: in Valentina’s ‘vision’ of Dolores’ murder, she sees Dolores being beaten about the face by Henri, who wields a spiked metal glove. Later, the glove is used again, by another perpetrator, to destroy the face of a woman. The filmmakers almost invite the audience to read these sequences as the forces of patriarchy enacting their revenge upon beautiful women by destroying their faces. Elsewhere, gender roles are subtly displaced: in one sequence, Stefano enters Valentina’s apartment and seats himself on her sofa, his cross-legged pose mirroring that of the feminine doll that sits on the sofa beside him. The representation of male-female relationships, however, is unambiguously cynical. Early in the film, Valentina attempts a reconciliation with Stefano. ‘I should have married you’, Valentina observes. ‘We’d be having an argument about that article’, Stefano responds dryly, referring to the article in Novella 2000 about Valentina’s supposed drug problem.

Video

Death Walks at Midnight was first released on DVD in the US by Mondo Macabro, in a version which cropped the film’s photography to 1.85:1. Later, it was released by NoShame in a double-bill with Death Walks on High Heels; that release restored the film’s photography to its full scope glory. Death Walks at Midnight was first released on DVD in the US by Mondo Macabro, in a version which cropped the film’s photography to 1.85:1. Later, it was released by NoShame in a double-bill with Death Walks on High Heels; that release restored the film’s photography to its full scope glory.

As each disc begins, the viewer is presented with the choice of watching the film with either English or Italian onscreen text, the latter of which is accompanied by optional English subtitles.

Both films are presented in their original aspect ratios of 2.35:1, and both pictures are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. Both films were shot in 2-perf widescreen processes with spherical lenses: Death Walks at Midnight was shot in Techniscope, and Death Walks on High Heels was shot in Cromoscope (both were essentially the same process but handled at different laboratories). Techniscope/Cromoscope and similar processes were cost-saving in the sense that they enabled the production of a widescreen image without the use of expensive anamorphic lenses, and by reducing the size of each frame by half (from 4-perforations to 2-perforations) halved the negative costs involved in making a film. (However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by more expensive lab costs, which for Techniscope productions steadily increased throughout the 1970s; this is sometimes cited as one of the reasons why Techniscope became less popular during the late 1970s and early 1980s.)

Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.) Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)

These characteristics of Techniscope (and similar processes) are evident in both of these films, which feature abundant use of short focal lengths and extraordinary depth of field even in low-light sequences. Interiors are filmed with a great sense of depth to the photography, especially in Death Walks at Midnight. (Death Walks at Midnight also features much use of vertical lines within the photography, which seem to be positioned with the intention of separating characters from one another within the frame, resulting in compositions that have the qualities of a diptych.) Both films are presented in new transfers from the original negatives, thus bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage. In the case of both pictures, contrast is rich and very well-balanced. Owing to the fact that the sources of both presentations were the films’ original negatives, blacks are deep and rich, more in line with Techniscope pictures processed using the dye transfer process than the later Techniscope pictures which were processed using the Kodak colour printing process (and which involved the production of a dupe negative that, as noted above, weakened contrast and produced a coarser grain structure). Likewise, the grain structure of both films is natural and organic and, owing to the source being a new transfer of the negative (bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage), without the coarseness that characterised some of the later prints of Techniscope films. The colour palette of both films is rich and saturated in a manner that looks ‘healthy’ and organic; Death Walks on High Heels has a palette that is a little more muted and naturalistic than Death Walks at Midnight.

Both films are presented uncut: Death Walks at Midnight runs for 101:50 mins, and Death Walks on High Heels runs for 107:48 mins.

At the bottom of this review are some screengrabs offering a comparison between Arrow’s new Blu-ray releases of both films and the NoShame DVD releases.

Audio

Both films are presented with the option of either an English or Italian audio track; in the case of both films, each of these tracks is in lossless DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono. On both discs, the English track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, whilst the Italian track is accompanied by optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. As both films were shot, in the manner of many Italian productions of this vintage, with an international cast and sound that was post-synched, neither audio track may be considered ‘definitive’. In terms of content, both tracks are essentially identical, with some very, very subtle differences in terms of content of the dialogue. Both films are presented with the option of either an English or Italian audio track; in the case of both films, each of these tracks is in lossless DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono. On both discs, the English track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, whilst the Italian track is accompanied by optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. As both films were shot, in the manner of many Italian productions of this vintage, with an international cast and sound that was post-synched, neither audio track may be considered ‘definitive’. In terms of content, both tracks are essentially identical, with some very, very subtle differences in terms of content of the dialogue.

The Italian track for Death Walks at Midnight segues into English for a brief scene in the detective’s office that wasn’t included in the Italian release prints. (This scene was presented in the same manner on the NoShame DVD release.) Both tracks for Death Walks at Midnight are clean and clear, though the Italian track sounds a little more ‘full bodied’, rich and rounded. On Death Walks on High Heels, both English and Italian tracks display much the same characteristics – though the English track here is arguably a little more shrill and ‘tinny’ than the Italian track.

In all cases, the subtitles are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

DISC ONE:

Death Walks on High Heels

This disc includes:

- an optional audio commentary with Tim Lucas. Lucas demonstrates his usual attention to detail, delivering a commentary track that is filled with anecdotal information about the production and reception of the film, and engages with some of its themes too. - an optional audio commentary with Tim Lucas. Lucas demonstrates his usual attention to detail, delivering a commentary track that is filled with anecdotal information about the production and reception of the film, and engages with some of its themes too.

- an optional introduction by Ernesto Gastaldi (1:48). Here, Gastaldi provides a brief précis of the film’s major themes. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘From Spain with Love’ (24:21). Recorded in 2012, this features Luciano Ercoli and Susan Scott. Ercoli reflects on how he came to be involved in filmmaking, from humble beginnings as a runner to working as an assistant director on the films of Carlo Ponti and De Laurentiis. Scott, on the other hand, discusses her attitude to filmmakng: she wasn’t passionate about cinema but ‘had fun’ making films. She transitioned into acting from modeling simply because ‘it was time for a change’. Ercoli reflects on the Italian Westerns that on which he worked, and how he came to make his first thrilling all’italiana, Le foto proibite…. Ercoli also discusses his relationship with Gastaldi, who he claims ‘wasn’t a great screenwriter, but he had certain ideas for thrillers. He always had remarkable ideas that he didn’t develop very well’. The interviews are in Italian and Spanish, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Master of Giallo’ (32:33). This interview with Gastaldi was shot in 2015 and is new to this release. Gastaldi talks about his approach to writing gialli all’italiana. For Gastaldi, ‘classic’ thrillers include the types of Clouzot’s Le corbeau (The Raven); these are films which feature few characters and sets. Gastaldi differentiates thrillers which ‘come from the head’ and suspense pictures that ‘come from the gut’; Argento’s gialli all’italiana fall into the latter category, Gastaldi suggests, and are therefore not ‘pure’ thrillers. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Death Walks to the Beat’ (26:28). This is another new interview, this time with Stelvio Cipriani, the film’s composer. Beginning with Cipriani playing the film’s main title on a piano, the interview finds the composer reflecting on how he came to be involved in writing the music for Death Walks on High Heels. He discusses the process of writing and recording the film’s score and the use of a vocal track in the film’s main theme, performed by Nora Orlandi. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- Trailers (5:37).

DISC TWO:

Death Walks at Midnight

This disc includes:

- another optional commentary with Tim Lucas. This is as well-researched as Lucas’ commentary for the first film in this set. - another optional commentary with Tim Lucas. This is as well-researched as Lucas’ commentary for the first film in this set.

- an optional introduction by Gastaldi (1:57). This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Crime Does Pay’ (32:02). In another newly-shot interview with Gastaldi, the screenwriter talks about how he came to work in films and talks about his abortive career as a director. He discusses his work with Sergio Leone and his work writing Westerns, before reflecting on the writing of some of the other films for which he is known. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Desperately Seeking Susan’ (27:53). This new video essay, written and narrated by Michael Mackenzie, reflects on the examples of the thrilling all’italiana in which Susan Scott starred. Mackenzie begins by discussing the woman-in-peril giallo all’italiana more generally before examining Scott’s films, describing Scott as ‘the anti-Edwige Fenech’.

- an alternate TV version of the film (106:03). Presented in 4:3 and seemingly from a videotape source, this alternate English language cut of the film incorporates some footage not included in the theatrical cut. It’s an excellent addition to the set and is particularly welcome.

Retail copies also include a sixty page book with essays by critics Danny Shika, Troy Howarth and Leonard Jacobs, illustrated with some amazing archival stills.

Overall

Both Death Walks on High Heels and Death Walks at Midnight feature the tropes of the ‘woman-in-peril’ form of the Italian thrilling: a metropolitan setting, at least for part of the film; a spunky young female protagonist who is involved in the arts (in Midnight, as a fashion model; in High Heels, as a dancer); a general sense of paranoia and conspiracy; and an emphasis on fashions and décor that, today, may seem garish. Both films also offer an overdose of kitsch: in the opening sequence of Death Walks at Midnight, for example, Valentina returns home to her swanky apartment – along one wall of which is a huge blow-up of a photograph of herself – whilst on the soundtrack we hear Gianni Ferrio’s main title theme for the picture on which a female vocalist breathily sings the word ‘Valentina’ repeatedly. Both Death Walks on High Heels and Death Walks at Midnight feature the tropes of the ‘woman-in-peril’ form of the Italian thrilling: a metropolitan setting, at least for part of the film; a spunky young female protagonist who is involved in the arts (in Midnight, as a fashion model; in High Heels, as a dancer); a general sense of paranoia and conspiracy; and an emphasis on fashions and décor that, today, may seem garish. Both films also offer an overdose of kitsch: in the opening sequence of Death Walks at Midnight, for example, Valentina returns home to her swanky apartment – along one wall of which is a huge blow-up of a photograph of herself – whilst on the soundtrack we hear Gianni Ferrio’s main title theme for the picture on which a female vocalist breathily sings the word ‘Valentina’ repeatedly.

Death Walks on High Heels is a much more ‘conventional’ thriller, which apes Psycho in its structure and relies heavily on cultural stereotypes (the English are repressed; the French are sexually liberated). It seems to look sideways towards the Edgar Wallace adaptations that were popular during the period of its production. It’s hampered slightly by a double climax but is a fun film to watch nonetheless. However, Death Walks at Midnight is a much more consistent and original film. Thematically, in terms of its focus on hallucinogens, the subconscious and repressed memories, it seems very much of its time, and the pacing is helped by the intrusion of some potent setpieces punctuated by gruesome moments of violence.

Both films are worth watching, though Midnight is arguably the most interesting of the two. Arrow’s presentation of both films is very good, offering a notable improvement over the films’ previous DVD releases. The release also contains some excellent and thorough contextual material. Fans of the thrilling all’italiana will find this release to be a very worthy purchase.

References:

Dyer, Richard, 2015: Lethal Repetition: Serial Killing in European Cinema. London: British Film Institute

Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Maryland: Scarecrow Press

Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland

Visual comparison between Arrow’s Blu-ray presentations and NoShame’s DVD releases of both films.

Death Walks on High Heels

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Death Walks at Midnight

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Arrow:

NoShame:

Death Walks on High Heels

Death Walks at Midnight

|