|

The Film

Female Prisoner Scorpion Collection Female Prisoner Scorpion Collection

After a number of years playing supporting roles in Nikkatsu productions (as Masako Ôto, her birth name), Kaji Meiko acquired a reputation as a lead actress in action-oriented films through her role in the five Stray Cat Rock films, beginning with Hasebe Yashuhara’s Stray Cat Rock: Delinquent Girl Boss in 1970. Kaji left Nikkatsu when the studio turned its attention towards producing Roman Porno pictures. During this time, Kaji found fame as a singer and acted in a number of action films for other studios before appearing in the lead role of all four of Toei’s Female Convict Scorpion (or Female Prisoner Scorpion) series of films; these were based on Tôru Shinohara’s Sasori manga series, which began publication in 1970.

The original intention was to make ten films based on Tôru’s manga, but the director of the first three films, Itô Shunya, left the series prior to the fourth picture, leaving the fourth film (Female Prisoner Scorpion: 701’s Grudge Song, 1973) to be helmed by Hasebe Yasuhara. After this film, Kaji left the series too, leaving it without the star whose presence had anchored and defined it. Toei continued to make Female Prisoner Scorpion pictures intermittently, but with neither Itô, Hasebe nor (especially) Kaji, they were lackluster. In Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film, Chris Desjardins describes the films as a ‘surreal, important footnote to the 1970s female yakuza genre’, suggesting they are ‘transcendental examples of violent seventies cinema’ (Desjardins, 2005: 224).

The first film, Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion (Itô Shunya, 1971) opens as Goda (Watanabe Fumio), the warden of the prison in which the films’ protagonist, Nami Matsushima (Matsu, for short, or ‘Scorpion’; played by Kaji Meiko), is being held is receiving a commendation. The guards are lined up neatly, saluting the flag, when an alarm signaling an escape attempt sounds. Matsu and Yuki (Watanabe Yoyoi), another of the female prisoners, have managed to flee from the prison; they are pursued across marshland by the guards. Yuki collapses; Matsu stays with her. Both women are caught and beaten cruelly by the guards. The first film, Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion (Itô Shunya, 1971) opens as Goda (Watanabe Fumio), the warden of the prison in which the films’ protagonist, Nami Matsushima (Matsu, for short, or ‘Scorpion’; played by Kaji Meiko), is being held is receiving a commendation. The guards are lined up neatly, saluting the flag, when an alarm signaling an escape attempt sounds. Matsu and Yuki (Watanabe Yoyoi), another of the female prisoners, have managed to flee from the prison; they are pursued across marshland by the guards. Yuki collapses; Matsu stays with her. Both women are caught and beaten cruelly by the guards.

Humiliated by the escape attempt, and especially its timing, the warden has the senior guards beat the junior guards. In turn, these junior guards take out their frustrations on the prisoners. Matsu and Yuki are thrown in solitary confinement. Flashbacks reveal that Matsu is in prison for attacking her lover Sugimi (Natsuyagi Isao), a police detective who used Matsu in an undercover role – allowing her to be raped and beaten by a group of gangsters he was investigating, in order to score a high profile arrest and achieve kudos and a promotion. Worried that Matsu might start to talk about what Sugimi did to her, Sugimi’s superior proposes using a female convict, Katagiri (Yokoyama Rie), to assassinate Matsu – with the promise to Katagiri that she will achieve the parole she desires.

When a fight breaks out between Matsu and another inmate, Masaki (Mihara Yôko), it results in Masaki lunging at Matsu with a shard of glass and, when Matsu dodges out of the way, spearing Goda in the eye, partially blinding him. Goda reacts by punishing all of the women severely, making them dig an enormous hole in the prison yard. This is the beginning of what is referred to as ‘The Devil’s Punishment’: at the bottom of the hole, Matsu must continue to dig downwards, whilst the other inmates at the top attempt to fill the hole in. The women must work day and night, with no rest. Violence erupts, and a group of the women attack the guards, taking them hostage. Intent on saving face and ridding himself of the problematic Matsu, Goda makes plans to rescue the guards and quell the rebellion. When a fight breaks out between Matsu and another inmate, Masaki (Mihara Yôko), it results in Masaki lunging at Matsu with a shard of glass and, when Matsu dodges out of the way, spearing Goda in the eye, partially blinding him. Goda reacts by punishing all of the women severely, making them dig an enormous hole in the prison yard. This is the beginning of what is referred to as ‘The Devil’s Punishment’: at the bottom of the hole, Matsu must continue to dig downwards, whilst the other inmates at the top attempt to fill the hole in. The women must work day and night, with no rest. Violence erupts, and a group of the women attack the guards, taking them hostage. Intent on saving face and ridding himself of the problematic Matsu, Goda makes plans to rescue the guards and quell the rebellion.

The second film, Jailhouse 41 (Itô Shunya, 1971), opens with Matsu once again in solitary confinement. Her hands and feet bound, she crafts a shiv by placing the handle of a metal spoon between her teeth and scraping the bowl against the concrete floor and walls of her cell. Goda is intent on driving Matsu insane; he believes he has beaten her, but when Matsu is forced to join the others for the visit of an official, she surprises Goda by leaping at him with her shiv, attempting to gouge out his good eye. The government official falls back to the floor and pisses himself in fear.

In response to this transgression, Goda orders that all of the women be punished severely. They are made to drag heavy rocks whilst Matsu is crucified and then, in front of the rest of the prisoners, gang raped by several of the guards who are dressed in bizarre costumes and masks. Transported back to the prison from the quarry where this outrage took place, Matsu fakes her death and strangles a guard with her chains, allowing herself and several other prisoners to escape. In response to this transgression, Goda orders that all of the women be punished severely. They are made to drag heavy rocks whilst Matsu is crucified and then, in front of the rest of the prisoners, gang raped by several of the guards who are dressed in bizarre costumes and masks. Transported back to the prison from the quarry where this outrage took place, Matsu fakes her death and strangles a guard with her chains, allowing herself and several other prisoners to escape.

The women flee across the barren landscape, encountering an abandoned village where they survive by killing and eating stray dogs, before finding an elderly woman who may or may not be a witch (‘I curse you. I will kill you’, this woman promises). The convicts are pursued across this landscape by the prison guards. On their way, the convicts encounter a group of tourists traveling by coach. But Summer Holiday, this isn’t: amongst the tourists are four former men who served in the Japanese army during the Second World War. They boast of raping Chinese women during Japan’s occupation of China, and when they spot Rose (Ishii Kuniko), one of the convicts, alone by a river they rape her and throw her body into the raging waters below. Discovering this crime, the other convicts take the entire coach of tourists hostage, leading to a standoff between them and Goda’s phalanx of prison guards.

In the opening sequence of the series’ third entry, Beast Stable (Itô Shunya, 1973), Matsu is shown on the subway. Recognised by detectives, she flees. One of the detectives, Kondo (Narita Mikio), manages to handcuff her to himself, but Matsu jumps off the train as the doors close and the train pulls out of the station, severing the arm of the detective. In the opening sequence of the series’ third entry, Beast Stable (Itô Shunya, 1973), Matsu is shown on the subway. Recognised by detectives, she flees. One of the detectives, Kondo (Narita Mikio), manages to handcuff her to himself, but Matsu jumps off the train as the doors close and the train pulls out of the station, severing the arm of the detective.

Living as a fugitive, Matsu encounters Yuki (Watanabe Yayoi), a young woman who lives with her brother who suffered brain damage in an industrial accident. It soon becomes clear that Yuki is engaged in a sexual relationship with her own brother, and Yuki reveals that she is pregnant by him. Meanwhile, it soon becomes clear that the area is ruled by a yakuza gang with a ‘stable’ of prostitutes. This group metes out severe punishments, administered by a sadistic woman named Katsu (Ri Reisen) (whom Matsu met in prison), to women they believe to be infringing upon their turf. One member of this gang, Tanida (Fujiki Takashi), recognises Matsu and tries to blackmail her into a sexual relationship (‘You can either be my woman or I’ll hand you over to the cops’). Matsu responds by killing Tanida, but this draws the ire of the yakuza gang, who demand Matsu ‘pay us damages with her body if she’s got no money’. Recognising Matsu, Katsu suggests that as she’s a fugitive she ‘won’t squeal to the cops’ and the gang can therefore ‘work [her] till she drops dead’.

Matsu is placed in an indoor aviary with Katsu’s pet crows. When Katsu punishes one of the prostitutes within her gang’s ‘stable’ by forcing her to undergo an illegal abortion, the victim is placed next to the aviary in which Matsu is held captive; the girl dies, giving Matsu the incentive to escape from the aviary and take revenge. Matsu first kills the doctor, then works her way through the gang members. These murders are investigated by Kondo, who is intent on seeking retribution for the loss of his arm. Fearing for her life, Katsu turns herself in to the police, begging to be returned to prison for her crimes (‘I guess rotten prison food is better than getting killed’, one of the police officers observes). Matsu hides from the police in the city’s sewers, where Yuki brings her provisions each day. However, Kondo catches up with Yuki and, using her brother and her pregnancy as leverage, forces her to give up where Matsu is hiding. The police set fire to the sewers, but Matsu miraculously escapes. Now she must seek revenge against both Kondo and Katsu. Matsu is placed in an indoor aviary with Katsu’s pet crows. When Katsu punishes one of the prostitutes within her gang’s ‘stable’ by forcing her to undergo an illegal abortion, the victim is placed next to the aviary in which Matsu is held captive; the girl dies, giving Matsu the incentive to escape from the aviary and take revenge. Matsu first kills the doctor, then works her way through the gang members. These murders are investigated by Kondo, who is intent on seeking retribution for the loss of his arm. Fearing for her life, Katsu turns herself in to the police, begging to be returned to prison for her crimes (‘I guess rotten prison food is better than getting killed’, one of the police officers observes). Matsu hides from the police in the city’s sewers, where Yuki brings her provisions each day. However, Kondo catches up with Yuki and, using her brother and her pregnancy as leverage, forces her to give up where Matsu is hiding. The police set fire to the sewers, but Matsu miraculously escapes. Now she must seek revenge against both Kondo and Katsu.

In the final picture, #701’s Grudge Song (Hasebe Yasuhara, 1973), Matsu is shown escaping from the police when they catch up with her at a wedding ceremony where she has sought employment. Badly injured in her involvement with the police, she finds her way into the basement of a seedy strip club where former student activist Kudo (Tamura Masakau) is employed. Having been tortured by the police, who whipped him and scalded his genitals to such an extent that they do not function any more, Kudo recognises Matsu as a fugitive immediately and sympathises with her, sheltering her from the detectives that come looking for her. Kudo attempts to help Matsu gain revenge against the detectives who are attempting to capture her. The police close in on the pair, leading to a shootout between the police and Kudo.

Kudo draws Matsu in to helping him stage a heist, but he is caught by the police and once again tortured both physically and psychologically. Matsu is left to fend for herself, and the police corner her in a scrapyard. There, she is captured. Returned to prison, Matsu is sentenced to hang. However, she forges a cunning plan to turn the tables against her captors. Kudo draws Matsu in to helping him stage a heist, but he is caught by the police and once again tortured both physically and psychologically. Matsu is left to fend for herself, and the police corner her in a scrapyard. There, she is captured. Returned to prison, Matsu is sentenced to hang. However, she forges a cunning plan to turn the tables against her captors.

The films are visually excessive and feature more or less unconventional narratives. As Desjardin notes, the pictures ‘possess traditional exploitation traits but with a surreal, comic book use of color and mythical, archetypal images’ (Desjardins, op cit.: 62). Jesus Franco’s 99 Women (1968) was the film that took the WIP (Women in Prison) picture away from its association with the ‘social problem’ film (for example, J Lee Thompson’s 1956 picture about a female murderer, Yield to the Night) towards an emphasis on salacious group shower scenes, depictions of lesbian sexuality riddled with cruel power games, and a cod-feminist critique of the patriarchal structures which imprison, regulate and control women’s bodies and sexuality. Franco’s film set the template for many subsequent WIP pictures. The Female Prisoner Scorpion films show some strong similarities with the WIP pictures being made in Europe at the time: the first picture, #701: Scorpion features under its opening titles a montage showing the female prisoners showing and being forced to pass by the gaze of the male guards. Via the cruel treatment of Matsu and the other female inmates, which escalates with each entry into the series, and Matsu’s ongoing rebellion against the patriarchal authority represented through the prison itself and the regime within it, the series has been interpreted as a crypto-feminist parable, with Matsu herself as an icon of female empowerment. The sense of repression of women’s bodies and identities within the prison is outlined in the opening sequence of the first film when, as Matsu and Yuji flee across the marshland surrounding the prison, Yuji collapses, blood streaming down her leg. As Yuki looks on in shock, Matsu informs her, ‘Yuki, it’s just your period. You didn’t have it for a long time because you were locked up’.

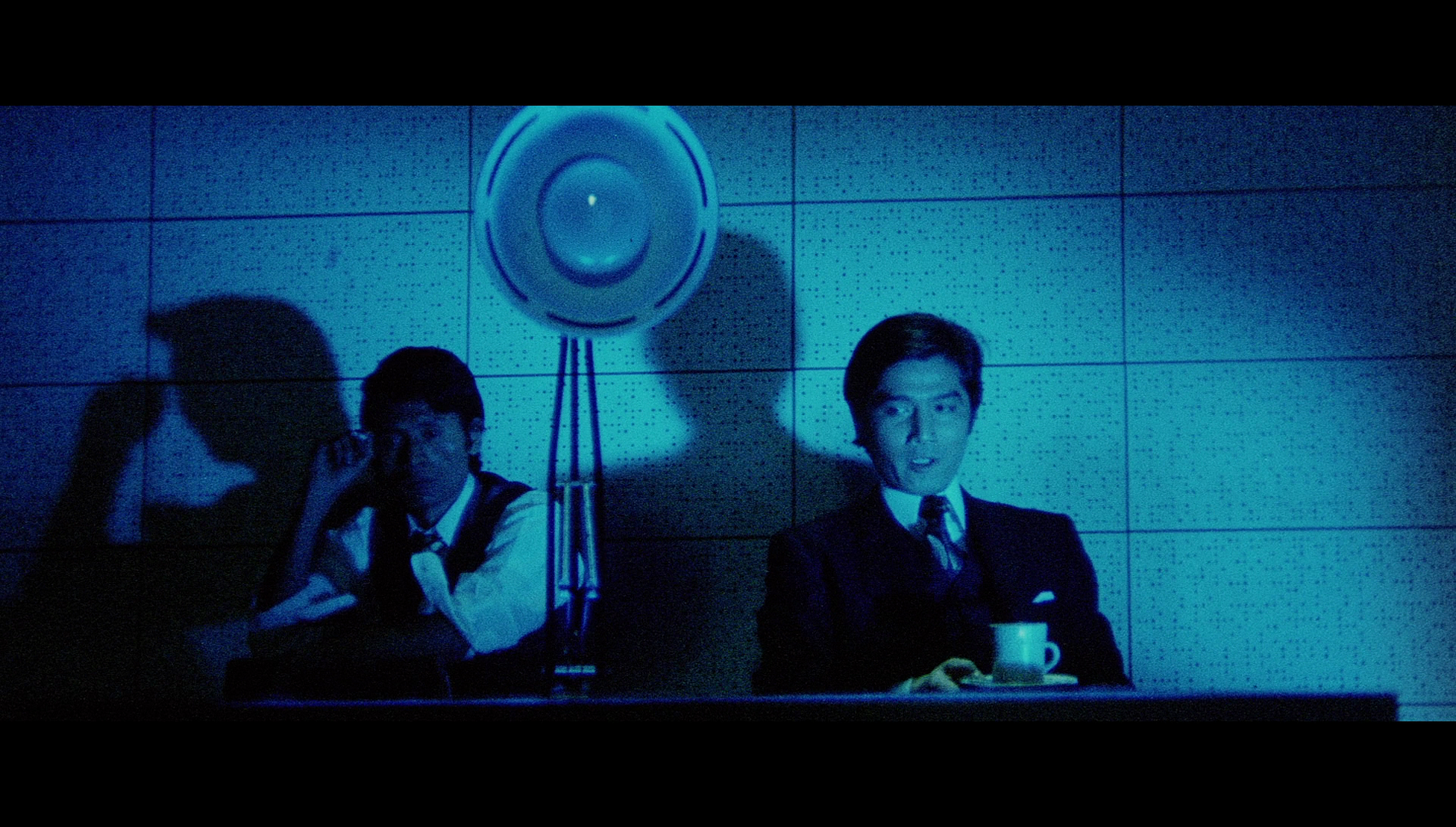

The final entry into the series #701’s Grudge Song, directed by Hasebe Yasuhara following Itô Shunya’s departure from the series, is stylistically different from the other pictures and feels very different in tone – though Matsu is the same almost supernatural force for vengeance she is in the other pictures. In the special features on this disc, Kazuyoshi Kumakiri describes Hasebe’s films as ‘quite manly’, and certainly men play a stronger and more complex role in this film, with Kudo offering a counterpart to Matsu for much of the film’s running time. The film weaves into its story references to the student rebellions of the 1960s; the flashbacks to Kudo’s torture at the hands of the police, presented via grainy and high-contrast monochrome imagery, haunt the picture and are cruel and brutal. (The effect is not dissimilar to the moment in Ted Kotcheff’s First Blood, 1982, in which Stallone’s John Rambo flashes back to his torture in Viet Nam whilst he is being humiliated by the deputies under the leadership of Brian Dennehy’s sheriff.) Kudo is one of the few sympathetic male characters in the series, shielding Matsu from the police but suffering cruelly for it. Perhaps significantly and related to the fact that unlike the other men in these films he is so sympathetic, he is also unable to function sexually. He is introduced operating the lights in a porno theatre whilst two women have sex on the stage in front of an audience. One of the female employees enters Kudo’s booth and comments, ‘I hear you don’t like girls. I’m here to fix that for you’. She unzips his flies and puts her hand in his trousers before recoiling in disgust: ‘Your thing!’, she cries, ‘It’s all messed up!’ (Later, it’s revealed that this is as a consequence of the torture Kudo sustained at the hands of the police during his days as a student activist; in one interrogation, shown on screen in high contrast monochrome photography, Kudo’s genitals were scolded with boiling water.) The final entry into the series #701’s Grudge Song, directed by Hasebe Yasuhara following Itô Shunya’s departure from the series, is stylistically different from the other pictures and feels very different in tone – though Matsu is the same almost supernatural force for vengeance she is in the other pictures. In the special features on this disc, Kazuyoshi Kumakiri describes Hasebe’s films as ‘quite manly’, and certainly men play a stronger and more complex role in this film, with Kudo offering a counterpart to Matsu for much of the film’s running time. The film weaves into its story references to the student rebellions of the 1960s; the flashbacks to Kudo’s torture at the hands of the police, presented via grainy and high-contrast monochrome imagery, haunt the picture and are cruel and brutal. (The effect is not dissimilar to the moment in Ted Kotcheff’s First Blood, 1982, in which Stallone’s John Rambo flashes back to his torture in Viet Nam whilst he is being humiliated by the deputies under the leadership of Brian Dennehy’s sheriff.) Kudo is one of the few sympathetic male characters in the series, shielding Matsu from the police but suffering cruelly for it. Perhaps significantly and related to the fact that unlike the other men in these films he is so sympathetic, he is also unable to function sexually. He is introduced operating the lights in a porno theatre whilst two women have sex on the stage in front of an audience. One of the female employees enters Kudo’s booth and comments, ‘I hear you don’t like girls. I’m here to fix that for you’. She unzips his flies and puts her hand in his trousers before recoiling in disgust: ‘Your thing!’, she cries, ‘It’s all messed up!’ (Later, it’s revealed that this is as a consequence of the torture Kudo sustained at the hands of the police during his days as a student activist; in one interrogation, shown on screen in high contrast monochrome photography, Kudo’s genitals were scolded with boiling water.)

Throughout the films, Matsu utters very few words, remaining silent for much of the pictures’ running times. (This is particularly noticeable in Jailhouse 41.) Kaji has said that this was because when Itô approached her to star in the film, the director lent her the Sasori manga, and when Kaji saw the script for the first film she noticed that Matsu’s dialogue ‘had kept most of the obscenities the character spoke in the comics’ (Kaji, quoted in Desjardins, op cit.: 68). Kaji told the producers that this was ‘unacceptable, that it would end up making the film seem cheap and sleazy, and that taking them out was one of my conditions for accepting the role’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). She and Itô came to an agreement that ‘it would be more interesting if my character hardly spoke any dialogue, except for a few important sentences’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). As a result, the filmmakers worked hard to express visually, through aspects of performance and photography, what Matsu was thinking and feeling (ibid.). Rikke Schubart has said that in these films, Matsu’s silence denotes her as ‘unbreakable, a mute symbol of male betrayal and social injustice’; her goal is not only revenge against the man who wronged her, but also against ‘the system he represents’ (Schubart, 2007: 111). As the series progresses, Matsu becomes an almost supernatural figure too; this is particularly noticeable in Beast Stable, when after escaping from the aviary in which she has been placed by Katsu, Matsu takes revenge against the male head of the yakuza gang by claiming she has been possessed by the girl who died from the botched abortion and seemingly magically producing a crow, which flies towards the gangster causing him to fall backwards out of a window on the upper floor of the building. Later in the same film, Kondo blackmails Yuki into revealing that Matsu is hiding in the sewers, and he tries to burn Matsu out of her hiding place. We see the sewers turned into a raging inferno from which it seems impossible that anything would survive. However, afterwards we are shown Matsu, in a low angle shot that reinforces her power and autonomy, emerging from the waters of the sewer – suggesting she was hiding beneath the surface of the water whilst the fire raged on. Throughout the films, Matsu utters very few words, remaining silent for much of the pictures’ running times. (This is particularly noticeable in Jailhouse 41.) Kaji has said that this was because when Itô approached her to star in the film, the director lent her the Sasori manga, and when Kaji saw the script for the first film she noticed that Matsu’s dialogue ‘had kept most of the obscenities the character spoke in the comics’ (Kaji, quoted in Desjardins, op cit.: 68). Kaji told the producers that this was ‘unacceptable, that it would end up making the film seem cheap and sleazy, and that taking them out was one of my conditions for accepting the role’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). She and Itô came to an agreement that ‘it would be more interesting if my character hardly spoke any dialogue, except for a few important sentences’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). As a result, the filmmakers worked hard to express visually, through aspects of performance and photography, what Matsu was thinking and feeling (ibid.). Rikke Schubart has said that in these films, Matsu’s silence denotes her as ‘unbreakable, a mute symbol of male betrayal and social injustice’; her goal is not only revenge against the man who wronged her, but also against ‘the system he represents’ (Schubart, 2007: 111). As the series progresses, Matsu becomes an almost supernatural figure too; this is particularly noticeable in Beast Stable, when after escaping from the aviary in which she has been placed by Katsu, Matsu takes revenge against the male head of the yakuza gang by claiming she has been possessed by the girl who died from the botched abortion and seemingly magically producing a crow, which flies towards the gangster causing him to fall backwards out of a window on the upper floor of the building. Later in the same film, Kondo blackmails Yuki into revealing that Matsu is hiding in the sewers, and he tries to burn Matsu out of her hiding place. We see the sewers turned into a raging inferno from which it seems impossible that anything would survive. However, afterwards we are shown Matsu, in a low angle shot that reinforces her power and autonomy, emerging from the waters of the sewer – suggesting she was hiding beneath the surface of the water whilst the fire raged on.

For Schubart, the films offer an explicit denouncement ‘of all men and all masculinity being destructive by nature’ (Schubart, op cit.: 116). As Schubart notes, the crimes of the women in the films, outlined in a sequence in Jailhouse 41 in which a voiceover narration identifies the reasons why each woman in Matsu’s group has been convicted, ‘relate to betrayal and disappointment, to anger and jealousy, and to the impossibility of female dignity in a patriarchal society’ (ibid.). In the second film, the elderly woman that the escaped convicts encounter in the abandoned village reflects on each woman’s crime before telling them ‘Women commit crimes because of men, driven by love, hatred and jealousy’. ‘To be deceived is a woman’s crime’, Matsu tells her nemesis at the end of the first picture.

A recurring moment within the films is the suggestion made by men that because the female convicts have been isolated from society, they are desperate for sexual encounters with strange men. One of the tourists on the coach in the second film asserts, when they are warned that the escaped prisoners are in the area, ‘Sounds interesting [….] If they’ve been in prison, they’ll be hungry for men’. Similarly, in the third film Tanida assaults Matsu, suggesting to her that ‘You’re so starved for sex, your body is on fire’.

Sexuality is here represented as a tool of power and a means of control. The women are raped and sexually assaulted by the guards as a means of asserting and consolidating the hierarchies within the prison. In one sequence in the first film, Matsu turns this methodology against her captors. Whilst she is in solitary confinement, another prisoner is brought in – supposedly for a similar punishment. Matsu soon realises something is amiss: the prisoner is in fact complicit with Goda, the warden. (It’s unclear whether she is an employee of the prison or simply a favoured inmate.) During the night, Matsu silently seduces this young woman, performing oral sex on her until she climaxes, the other ‘inmate’ begging ‘Please, more. I want more!’ as Matsu stands above her, filmed from a low angle to symbolise the power that Matsu has assumed within this scenario. When the woman is taken out of Matsu’s cell and returned to the warden, he asks her what she has discovered about Matu; but overcome with desire, the woman simply begs to be returned to solitary confinement with Matsu. It’s an absurd scenario but one which foregrounds how sexuality is used as a tool of power within the prison, and the extent to which the near-silent Matsu is able to assume and subvert/hijack this. Sexuality is here represented as a tool of power and a means of control. The women are raped and sexually assaulted by the guards as a means of asserting and consolidating the hierarchies within the prison. In one sequence in the first film, Matsu turns this methodology against her captors. Whilst she is in solitary confinement, another prisoner is brought in – supposedly for a similar punishment. Matsu soon realises something is amiss: the prisoner is in fact complicit with Goda, the warden. (It’s unclear whether she is an employee of the prison or simply a favoured inmate.) During the night, Matsu silently seduces this young woman, performing oral sex on her until she climaxes, the other ‘inmate’ begging ‘Please, more. I want more!’ as Matsu stands above her, filmed from a low angle to symbolise the power that Matsu has assumed within this scenario. When the woman is taken out of Matsu’s cell and returned to the warden, he asks her what she has discovered about Matu; but overcome with desire, the woman simply begs to be returned to solitary confinement with Matsu. It’s an absurd scenario but one which foregrounds how sexuality is used as a tool of power within the prison, and the extent to which the near-silent Matsu is able to assume and subvert/hijack this.

A more graphic demonstration of this idea appears later in the film, when the women have rioted and taken control of the prison, taking a number of guards hostage. Stripped to their knickers and under the command of a ringleader, several of the women advance upon the men with smiles upon their faces. The men push back in terror: the women have been commanded to rape the guards, turning the chief method used within the system of power and control within the prison against itself. A similar scenario plays out in the second films, when the escaped convicts take the coachload of tourists hostage in retaliation for the murder of Rose. Responding to the sexual torment of Rose in kind, the convicts strip and humiliate the men, asking them, ‘You think it’s okay to kill her because she’s a criminal?’ and asserting that ‘These passengers think they’re different from us. Let’s show them how wrong they are’. Of course, this violence enacted against the murderers of Rose escalates, as violence has a tendency to, and the convicts turn their attentions towards the other passengers, stripping and humiliating some of the women on the coach too.

What is arguably the most harrowing sequence in the series comes in the third film, Beast Stable. Here, Matsu encounters a former inmate of Goda’s prison, Katsu. Katsu has become assimilated herself into the system of male authority, functioning alongside a male gang boss as the co-leader of a group of yakuza in control of a ‘stable’ of prostitutes. Her role offers some of the more eccentric scenarios within the series, and also some of the most cruel. Dressed with clothes adorned with feathers and keeping pet crows (which caw with human voices) in an indoor aviary – in which, in the midportion of the picture, she keeps Matsu captive – Katsu is responsible for meting out punishments for those prostitutes whose actions are seen as transgressive or those from outside who trespass onto the gang’s turf. Katsu, it seems, has internalised the system of patriarchal violence, upping the ante in terms of cruelty. In one scene, Katsu punishes a woman who has solicited clients on the gang’s turf, thus offering competition to the young women working as prostitutes for Katsu’s gang: Katsu punishes this young woman for her transgression by raping her with a golf club and then forcing the bloody head of the club against the woman’s face. Later, Katsu inflicts the most unpleasant punishment in a sequence that is extremely difficult to watch: she forces one of the gang’s prostitutes, who is pregnant, to undergo an underground abortion. We watch as the young woman is held down, writhing and screaming against her captors, as the procedure is carried out. It’s an extraordinarily challenging scene, as are many in this series of films, but underscores the picture’s emphasis on power, exploitation, coercion and the lack of control women have over their own bodies. What is arguably the most harrowing sequence in the series comes in the third film, Beast Stable. Here, Matsu encounters a former inmate of Goda’s prison, Katsu. Katsu has become assimilated herself into the system of male authority, functioning alongside a male gang boss as the co-leader of a group of yakuza in control of a ‘stable’ of prostitutes. Her role offers some of the more eccentric scenarios within the series, and also some of the most cruel. Dressed with clothes adorned with feathers and keeping pet crows (which caw with human voices) in an indoor aviary – in which, in the midportion of the picture, she keeps Matsu captive – Katsu is responsible for meting out punishments for those prostitutes whose actions are seen as transgressive or those from outside who trespass onto the gang’s turf. Katsu, it seems, has internalised the system of patriarchal violence, upping the ante in terms of cruelty. In one scene, Katsu punishes a woman who has solicited clients on the gang’s turf, thus offering competition to the young women working as prostitutes for Katsu’s gang: Katsu punishes this young woman for her transgression by raping her with a golf club and then forcing the bloody head of the club against the woman’s face. Later, Katsu inflicts the most unpleasant punishment in a sequence that is extremely difficult to watch: she forces one of the gang’s prostitutes, who is pregnant, to undergo an underground abortion. We watch as the young woman is held down, writhing and screaming against her captors, as the procedure is carried out. It’s an extraordinarily challenging scene, as are many in this series of films, but underscores the picture’s emphasis on power, exploitation, coercion and the lack of control women have over their own bodies.

The first film was shot in sequence and took four months to complete, which was unusual for a Toei production at the time: most of their pictures were shot in three weeks (Kaji, quoted in Desjardins, op cit.: 69). However, Itô headed the union and pressure was placed on the Toei executives to comply with the production schedule required to complete the picture (ibid.). Owing to its success, the sequels were produced, and they upped the ante in terms of the cruelties enacted upon Matsu. Kaji asserted in interview that the more fantastical punishments underscored ‘[t]he whole thrust of each films’ scenario’, which was to ‘abuse and beat the Scorpion character until she once again exacted revenge at the climax’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). In the filming of some of the sequences, such as the sequence near the opening of Jailhouse 41 in which Matsu (and, for that matter, Kaji) is sprayed with cold water from a hose, ‘It became more a test of physical endurance rather than acting skill. I had to be concerned about not getting sick, not getting hurt on the set’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). She described the shoots as ‘so brutal’, and ‘the consciousness of each successive film became more and more grotesque, more radical just to maintain the audience, to make sure the pictures were hits’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). The first film was shot in sequence and took four months to complete, which was unusual for a Toei production at the time: most of their pictures were shot in three weeks (Kaji, quoted in Desjardins, op cit.: 69). However, Itô headed the union and pressure was placed on the Toei executives to comply with the production schedule required to complete the picture (ibid.). Owing to its success, the sequels were produced, and they upped the ante in terms of the cruelties enacted upon Matsu. Kaji asserted in interview that the more fantastical punishments underscored ‘[t]he whole thrust of each films’ scenario’, which was to ‘abuse and beat the Scorpion character until she once again exacted revenge at the climax’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). In the filming of some of the sequences, such as the sequence near the opening of Jailhouse 41 in which Matsu (and, for that matter, Kaji) is sprayed with cold water from a hose, ‘It became more a test of physical endurance rather than acting skill. I had to be concerned about not getting sick, not getting hurt on the set’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.). She described the shoots as ‘so brutal’, and ‘the consciousness of each successive film became more and more grotesque, more radical just to maintain the audience, to make sure the pictures were hits’ (Kaji, quoted in ibid.).

In Jailhouse 41, Matsu and a number of the other inmates escape from the prison and flee across a desolate landscape; the journey across the landscape seems highly symbolic, like Marlowe’s voyage along the Congo in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: a journey into the dark recesses of the soul. As they flee from the prison guards, they encounter various people, including an elderly woman who lives alone in a village that seems to have been decimated by the eruption of a volcano, and a coachful of tourists that include amongst the number a group of former soldiers, now salarymen on holiday, who boast of raping Chinese women during the Second World War era, before encountering one of the escaped female prisoners, a member of Matsu’s group, and subjecting her to the same fate before discarding her broken body in the raging waters of a waterfall which then turns red with blood symbolically. Chris Desjardins argues that Jailhouse 41 is a ‘transcendental, exhilarating masterpiece that is at times reminiscent of John Boorman’s Point Blank and Donald Cammell/Nicolas Roeg’s Performance in its sheer audacity’ (Desjardins, op cit.: 62).

The sense of a patriarchy that is cruel and defined by sadism is established in the opening moments of the first film, when Matsu and Yuji’s escape attempt results in the humiliated warden having his senior officers strike his junior officers, aware that the cycle of violence will spiral down towards those at the bottom of the ‘pecking order’, the inmates. Here, male authority is defined by cruelty and by a need to use violence to maintain the status quo and to punish transgressors, a theme that the series of films return to time and time again via the punishments meted out to Matsu and the other female inmates who ally themselves with her. In the first two films, in particular, Goda attempts to ‘divide and conquer’ the inmates, punishing them all because of Matsu’s escape attempt. At the climax of the first film, this comes to the fore when, after the rebellion, Katagiri attempts to turn the other women against Matsu, saying that it’s Matsu’s fault the women are in their current predicament, and is almost successful: Matsu is hogtied and hanged from the ceiling of the warehouse in which the women barricade themselves. Matsu is subjected to torture at the hands of her rival prisoners that rivals and arguably surpasses that inflicted on her by the guards: where the guards assaulted her sexually with a truncheon, it is implied that led by Katagiri and Masaki, Matsu’s fellow inmates burn her body with a hot electric lightbulb and subject her to a similar sexual assault with it (offscreen, thankfully). At night, Katagiri (who promises Matsu that ‘I’ll get them stirred up and torture you to death’) attempts to use an accelerant to start a fire beneath Matsu’s bound body. However, Matsu is saved by the guards, who gain entry to the warehouse; the fate Katagiri had in mind for Matsu is inflicted upon Katagiri herself. The sense of a patriarchy that is cruel and defined by sadism is established in the opening moments of the first film, when Matsu and Yuji’s escape attempt results in the humiliated warden having his senior officers strike his junior officers, aware that the cycle of violence will spiral down towards those at the bottom of the ‘pecking order’, the inmates. Here, male authority is defined by cruelty and by a need to use violence to maintain the status quo and to punish transgressors, a theme that the series of films return to time and time again via the punishments meted out to Matsu and the other female inmates who ally themselves with her. In the first two films, in particular, Goda attempts to ‘divide and conquer’ the inmates, punishing them all because of Matsu’s escape attempt. At the climax of the first film, this comes to the fore when, after the rebellion, Katagiri attempts to turn the other women against Matsu, saying that it’s Matsu’s fault the women are in their current predicament, and is almost successful: Matsu is hogtied and hanged from the ceiling of the warehouse in which the women barricade themselves. Matsu is subjected to torture at the hands of her rival prisoners that rivals and arguably surpasses that inflicted on her by the guards: where the guards assaulted her sexually with a truncheon, it is implied that led by Katagiri and Masaki, Matsu’s fellow inmates burn her body with a hot electric lightbulb and subject her to a similar sexual assault with it (offscreen, thankfully). At night, Katagiri (who promises Matsu that ‘I’ll get them stirred up and torture you to death’) attempts to use an accelerant to start a fire beneath Matsu’s bound body. However, Matsu is saved by the guards, who gain entry to the warehouse; the fate Katagiri had in mind for Matsu is inflicted upon Katagiri herself.

The second film begins with Goda attempting to ‘break’ Matsu by placing her in solitary confinement; at the time of the visit of the government official, the dialogue suggests that Matsu has been in solitary for a year. Goda believes he has ‘broken’ her, but she has spent the time preparing (fashioning a shiv out of a spoon) and planning her attack upon him. He is motivated by revenge, and she is motivated by a similar instinct, wishing to pluck out his remaining good eye. Entering the underground cell in which Matsu is being kept at the start of the film, Goda observes, ‘It sure is hell down here. Haven’t you gone crazy yet?’ He tells her, ‘You were nothing but a pest here. But now I’ve beaten you’; he warns her ‘you’ll never leave here. You’ll spend the rest of your life underground. That’s the price you have to pay for your crimes [….] For the rest of your life, you’ll never leave this place […] I’ll drive you mad, I swear. Go mad. Come on, go mad!’ Having failed to force Matsu to submit to his will, Goda punishes her by having her crucified and gang raped by several of the guards, warning his colleagues that ‘The name “Scorpion” […] will soon become the password of their riots. We must humiliate her in front of the others today’. For the rest of the film, Matsu remains silent, only speaking at the end of the picture; her silence makes her enigmatic, but also causes her to be treated with suspicion by some of the other women with whom she escapes the prison. The second film begins with Goda attempting to ‘break’ Matsu by placing her in solitary confinement; at the time of the visit of the government official, the dialogue suggests that Matsu has been in solitary for a year. Goda believes he has ‘broken’ her, but she has spent the time preparing (fashioning a shiv out of a spoon) and planning her attack upon him. He is motivated by revenge, and she is motivated by a similar instinct, wishing to pluck out his remaining good eye. Entering the underground cell in which Matsu is being kept at the start of the film, Goda observes, ‘It sure is hell down here. Haven’t you gone crazy yet?’ He tells her, ‘You were nothing but a pest here. But now I’ve beaten you’; he warns her ‘you’ll never leave here. You’ll spend the rest of your life underground. That’s the price you have to pay for your crimes [….] For the rest of your life, you’ll never leave this place […] I’ll drive you mad, I swear. Go mad. Come on, go mad!’ Having failed to force Matsu to submit to his will, Goda punishes her by having her crucified and gang raped by several of the guards, warning his colleagues that ‘The name “Scorpion” […] will soon become the password of their riots. We must humiliate her in front of the others today’. For the rest of the film, Matsu remains silent, only speaking at the end of the picture; her silence makes her enigmatic, but also causes her to be treated with suspicion by some of the other women with whom she escapes the prison.

As the flashbacks to Matsu’s life prior to her incarceration reveal, life on the outside of the prison isn’t much different to life on the inside: outside, Matsu was subjected to similar, though less overt, structures put in place on her life by her lover Sugimi, who used Matsu as bait to score a high profile arrest against some gangsters, allowing these thugs to rape and humiliate Matsu in the process. As Matsu suffers in prison, being raped with a truncheon by vindictive guards, we are shown Sugimi on the outside; his career is on the up. Sugimi’s superior asks Sugimi why Matsu didn’t testify against the police force at her trial. ‘Because she was still in love with me, that’s why’, Sugimi suggests arrogantly. When Matsu finally catches up with Sugimi at the end of the picture, he tells her spitefully, ‘The more you hate me, the more you can’t forget me. After all, I’m the one who made you a woman!’

Video

The films are all presented in their original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec. Each film is housed on a separate disc, and each film takes up approximately 24Gb of space on its respective disc. All four films are uncut. Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion runs for 86:56 mins; Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 runs for 88:43 mins; Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable runs for 87:13 mins; and Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song runs for 88:36 mins. The films are all presented in their original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec. Each film is housed on a separate disc, and each film takes up approximately 24Gb of space on its respective disc. All four films are uncut. Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion runs for 86:56 mins; Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 runs for 88:43 mins; Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable runs for 87:13 mins; and Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song runs for 88:36 mins.

The films are shot inventively, making use of obtuse angles and even shots in which the camera is positioned upside down or beneath a glass floor to shoot upwards (for example, the rape of Matsu at the hands of the gangsters in the first film). Abstract sets appear throughout the films, bathed in primary colours; in the sequence from the first film in which Matsu is betrayed by her lover and left for the gangsters to assault, the rear of the set, bathed in blue, shows itself to be a rotating wall.

The colour timing within these presentations has already proven to be controversial. Arrow were apparently provided by Toei with low contrast prints (struck from unspecified ‘original 35mm film elements’) for this presentation of all four films; the colour timing was baked into these prints by Toei. These prints were then scanned at 2k resolution to create the digital masters.

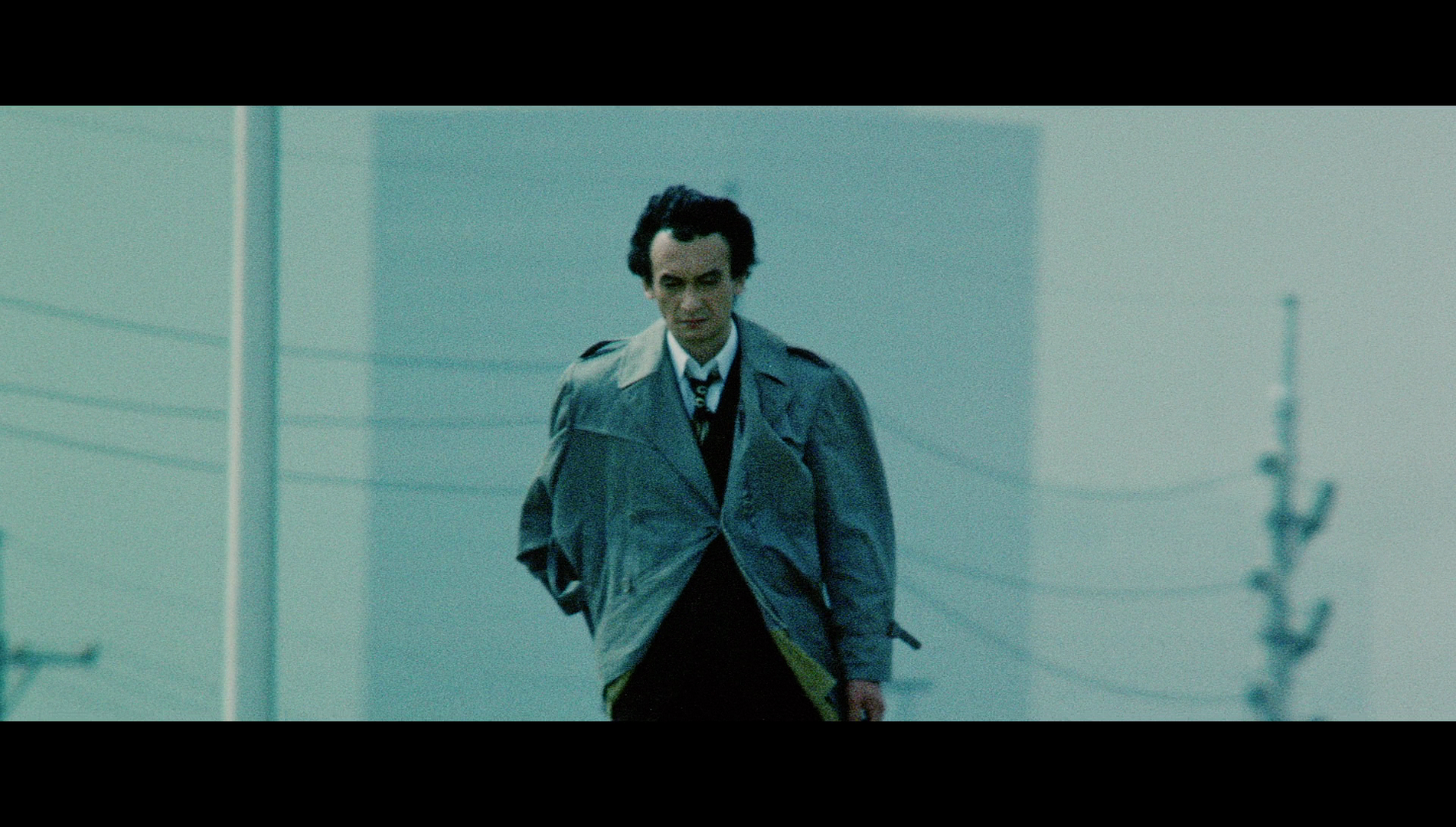

The presentations of all four films are starkly different from their previous home video presentations, featuring a stronger bias towards colder blues and greens (offset by a bolder use of ‘hot’ colours such as reds and oranges within the same frame). The appearance of all four films may or may not be closer to their original cinema presentations than previous home video releases (and it’s important to remember that previous home video releases can’t necessarily be used as a yardstick by which to measure how the films ‘should’ look or how they perhaps did look when first exhibited at cinemas). One may only speculate with regards this issue. However, in my opinion, as a (sometime published still) photographer who works with both 35mm film and digital photography, the use of colour in these presentations looks decidedly ‘digital’; as with Hammer’s controversial restoration of Terence Fisher’s Dracula (1958), the intent may very well have been to restore the films to the colour timing of their original prints – and, as with Dracula, this aesthetic goal may arguably have been achieved in the broadest sense that the bias and balance of colour within the image may indeed accurate to the original release prints (without access to one, who can tell?) – but this would seem to have been achieved digitally rather than via traditional photochemical processes. As a consequence, the viewer may find that the overall effect is unconvincing or appears ‘revisionist’; I would argue that if it does, it’s because a modern digital workflow seems to have been applied in the colour timing of the prints provided by Toei rather than the employment of traditional photochemical processes, so the use of colour within the films may be commensurate with the original prints but also feels very ‘modern’. The effect is particularly pronounced in the second picture, to the extent that skin tones are decidedly green throughout the film – and the performers look jaundiced because of it. The presentations of all four films are starkly different from their previous home video presentations, featuring a stronger bias towards colder blues and greens (offset by a bolder use of ‘hot’ colours such as reds and oranges within the same frame). The appearance of all four films may or may not be closer to their original cinema presentations than previous home video releases (and it’s important to remember that previous home video releases can’t necessarily be used as a yardstick by which to measure how the films ‘should’ look or how they perhaps did look when first exhibited at cinemas). One may only speculate with regards this issue. However, in my opinion, as a (sometime published still) photographer who works with both 35mm film and digital photography, the use of colour in these presentations looks decidedly ‘digital’; as with Hammer’s controversial restoration of Terence Fisher’s Dracula (1958), the intent may very well have been to restore the films to the colour timing of their original prints – and, as with Dracula, this aesthetic goal may arguably have been achieved in the broadest sense that the bias and balance of colour within the image may indeed accurate to the original release prints (without access to one, who can tell?) – but this would seem to have been achieved digitally rather than via traditional photochemical processes. As a consequence, the viewer may find that the overall effect is unconvincing or appears ‘revisionist’; I would argue that if it does, it’s because a modern digital workflow seems to have been applied in the colour timing of the prints provided by Toei rather than the employment of traditional photochemical processes, so the use of colour within the films may be commensurate with the original prints but also feels very ‘modern’. The effect is particularly pronounced in the second picture, to the extent that skin tones are decidedly green throughout the film – and the performers look jaundiced because of it.

Certainly, because the sources used for the presentations of all four films were prints rather than the films’ original negatives, and thus removed from the source material by several degrees, contrast seems rather ‘hot’ in these presentations, with the highlights blooming at times and detail crushed in the shadows. Additionally, the coarseness of the grain structure underscores the fact that the sources used here were positive prints. Certainly, because the sources used for the presentations of all four films were prints rather than the films’ original negatives, and thus removed from the source material by several degrees, contrast seems rather ‘hot’ in these presentations, with the highlights blooming at times and detail crushed in the shadows. Additionally, the coarseness of the grain structure underscores the fact that the sources used here were positive prints.

That said, if one is tolerant of the seemingly digital colour timing (and the large screengrabs at the bottom of this review should be an indicator of this), the presentations are in many other ways head and shoulders above previous home video releases, with an impressive level of detail present throughout all four films, and remarkable attention seems to have been paid to cleaning up instances of damage throughout the four films. Excellent encodes across all four discs ensure that the films retain the coarse grain structure mentioned in the paragraph above, and (aside from the use of colour) the whole experience of viewing the films feels very organic and film-like.

Audio

In the case of all four films, audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track in Japanese. These tracks are all clean and clear and display good range. Optional English subtitles are included which are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows:

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion

Extras:

- An appreciation by Gareth Evans (24:33). In a new interview, film director and cinephile Gareth Evans talks about his relationship with the Female Prisoner Scorpion films. He talks about the differences between these films and the Lady Snowblood pictures, which also starred Kaji Meiko; he argues that the Female Prisoner Scorpion films feature ‘interesting’ elements that are ‘theatrical’ and ‘beyond cinema’, like the moving sets. He discovers the impact of films such as these on his own career as a director too.

- Shunya Itô: Birth of an Outlaw (15:47). Originally shot for inclusion on a German DVD release, this interview with Itô is presented in edited form. The director talks about his intentions as a filmmaker and reflects on the social and political context in which he began his career as a director. He also talks about his work as a spokesman for the union. The interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- Yutara Kohira: Scorpion Old and New (14:46). In a new interview, assistant director Kohira Yutara reflects on his work on this film and on Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honour. He discusses some of the themes of the film and its origins in the popular manga. He suggests the films channeled some of Itô’s anti-establishment ideas, arguing that ‘it was as if his [Itô’s] anger towards the state was transformed into Scorpion’s anger’.

- Trailers: Female Prison #701: Scorpion (3:03); Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (3:11); Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable (3:08); Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song (3:14)

- Credits (0:55). Within the presentation of the main feature, Arrow have chosen to subtitle the song sung over the credits rather than the onscreen titles themselves. Here, we are presented with the credits for the film.

DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41

Extras:

- An appreciation by Kier-la Janisse (28:03). In a new interview, film programmer and critic Kier-la Janisse talks about her love for this series of films, reflecting on her first encounter with the series via a screening of Jailhouse 41. She suggests that the films are ‘a perfect mix of high art and exploitation’ that felt ‘very modern’ whilst also ‘very clearly mining much older Japanese traditions’. She suggests that the closest corollary for these films, in terms of how they depict sex and violence with ‘amazing art direction’, are perhaps the films of Radley Metzger. She discusses the films’ relationship with the female revenge picture generally.

- Jasper Sharp on the career of Shunya Itô (10:29). In another new piece, Jasper Sharp talks about the career of director Itô Shunya, which began with the first picture in this series of films. Sharp suggests that the flamboyance of the excess of the films may be quite a direct replication of the manga on which the series is based, and there are some specific images from the manga which work their way into the photography of these film adaptations.

- Tadayaki Kuwana: Designing Scorpion (16:35). In a new interview, production designer Kuwana talks about his role as art director on the films and his working relationship with Itô. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- Trailers: teaser (1:46); theatrical trailer (3:11).

- Credits (0:55). As per disc one.

DISC THREE: DISC THREE:

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable

Extras:

- An appreciation by Kat Ellinger (25:48). In a new interview, Ellinger talks about her first encounters with the films following a viewing of Lady Snowblood (Fujita Toshiya, 1973) and being impressed with Kaji Meiko’s performance in that picture. She considers the international appeal of the Female Prisoner Scorpion series.

- Shunya Itô: Directing Meiko Kaji (17:36). This interview with shot for a German DVD release of the film in 2006, and is presented her in an edited form. Itô discusses how he came to be attached to the Female Prisoner Scorpion series. He reflects on working with Kaji and discusses her approach to acting. He suggests that the atmosphere on the first film was ‘tense’ because he ‘wondered how far she [Kaji] was prepared to go’. The interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Unexplained Melody’: A Visual Essay by Tom Mes (21:29). Here, Tom Mes reflects on the Kaji Meiko’s career. This piece is anchored by Mes’ discussion of Kaji’s career-defining performances in Female Prisoner Scorpion and Lady Snowblood. He discusses the qualities of her work on screen and suggests that she may be considered, to some extent, to be a star-auteur.

- Trailer: teaser (1:46); theatrical trailer (3:08)

- Credits (0:55). As per disc one.

DISC FOUR: DISC FOUR:

Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song

Extras:

- An appreciation by Kazuyoshi Kumakiri (11:13). Here, in a new interview, Kazuyoshi Kumakiri reflects on his first experience with these films, suggesting that ‘Beautiful women behaving violently. That was very much to my taste’. He talks a little about Hasebe’s films generally, describing them as ‘quite manly’, and he reflects on the excesses of Female Prisoner Scorpion series of films. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- Yasuhara Hasebe: Finshing the Series (19:49). In this interview, shot in 2006 for a German DVD release and presented here in an edited form, Hasebe reflects on his approach to cinema and how this film differed from the previous films in the series – though Hasebe wanted to ensure as much continuity as possible with those pictures. This interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- Jasper Sharp on Yasuhara Hasebe (16:54). In another new interview, Jasper Sharp comments on the work of director Hasebe, reflecting on the relative rarity of 701’s Grudge Song on home video formats. Sharp discusses Hasebe’s work at Nikkatsu, leading onto this film, which was Hasebe’s first picture for Toei.

- ‘They Call Her Scorpion’: A Visual Essay by Tom Mes (40:00). Mes reflects on the production context in which the Female Prisoner Scorpion series was made, and how Nikkatsu and Toei came to make exploitation films as a response to declining audiences for pictures released to cinemas. Mes talks about the four films included here in much detail. This is an excellent, insightful piece, supported with plentiful clips from these films and from other pictures too.

- Trailer (3:13).

- Credits (0:55). As per disc one.

Overall

There’s a cumulative sense of growth within the first three pictures, with references to earlier events helping to create the sense of an ongoing narrative. The fourth film feels very different, thanks largely to the involvement of Hasebe as a director, it would seem. All four films are very good, but Hasebe’s picture has a very different texture to it and feels as if it’s part of another series of films. There’s a cumulative sense of growth within the first three pictures, with references to earlier events helping to create the sense of an ongoing narrative. The fourth film feels very different, thanks largely to the involvement of Hasebe as a director, it would seem. All four films are very good, but Hasebe’s picture has a very different texture to it and feels as if it’s part of another series of films.

In almost all ways, the presentations here are a vast improvement over the films’ previous home video releases. A much stronger level of detail is present throughout all four films. However, because the source for these presentations would seem to be positive prints, the structure of the image is very coarse and contrast is very bold – with shadow detail sometimes seeming to be ‘crushed’ and highlights blooming. Nevertheless, it’s all handled very nicely within the encode, which ensures that the presentations retain the organic structure of 35mm film, and the experience of watching these presentations feels very film-like. What’s destined to be more controversial is the colour timing, which particularly in the first three films (and especially in Jailhouse 41) has a tendency towards greens and blues lacking in previous home video presentations. As noted in the ‘Video’ section of this review, this seems to have been a characteristic of the masters provided by Toei and may indeed have been done with the best of intentions, but it feels as if it’s been achieved digitally and therefore feels rather ‘artificial’. Some viewers may find this tolerable; others may find it distracting. Certainly, the large screen grabs below should give a good indication of the merits of the presentations of all four films contained in this set.

The set is also packed with some superb contextual material covering all four films; these include reflections from the participants but also some critical commentary from those who admire the films, including director Gareth Evans and others such as the critic and film programmer Kier-la Janisse. Quibbles about the use of colour aside, this is a very pleasing release of four pictures which straddle the exploitation/arthouse divide in fascinating ways.

References:

Desjardins, Chris, 2005: Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I B Tauris

Schubart, Rikke, 2007: Super Bitches and Action Babes: The Female Hero in Popular Cinema, 1970-2006. London: McFarland & Company

Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable

Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song

|