|

The Film

The Early Works of Rainer Werner Fassbinder The Early Works of Rainer Werner Fassbinder

This release from Arrow collects the first two feature length pictures directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Liebe ist kälter als der Tod (Love is Colder Than Death, 1969) and Katzelmacher (also 1969), along with two of the director’s short films, ‘Der Stadtstreicher’ (‘The City Tramp’, 1966) and ‘Das kleine Chaos’ (‘The Little Chaos’, also 1966). These films were made during Fassbinder’s association with the Action Theatre group and, after 1968, his leadership of the ‘anti-teater’. Fassbinder had, apparently, always seen his work in theatre as a stepping stone towards making films (see Rheuban, 1986: 24). Certainly, by collaborating with members of the ‘anti-teater’ group, when he entered the world of filmmaking Fassbinder worked extremely quickly and economically, delivering ten experimental films between 1969 (the first of which was Love is Colder Than Death) and 1970 (ending with Beware of a Holy Whore). This period of Fassbinder’s career attracted strong critical praise and ensured that his subsequent pictures would benefit from government subsidies.

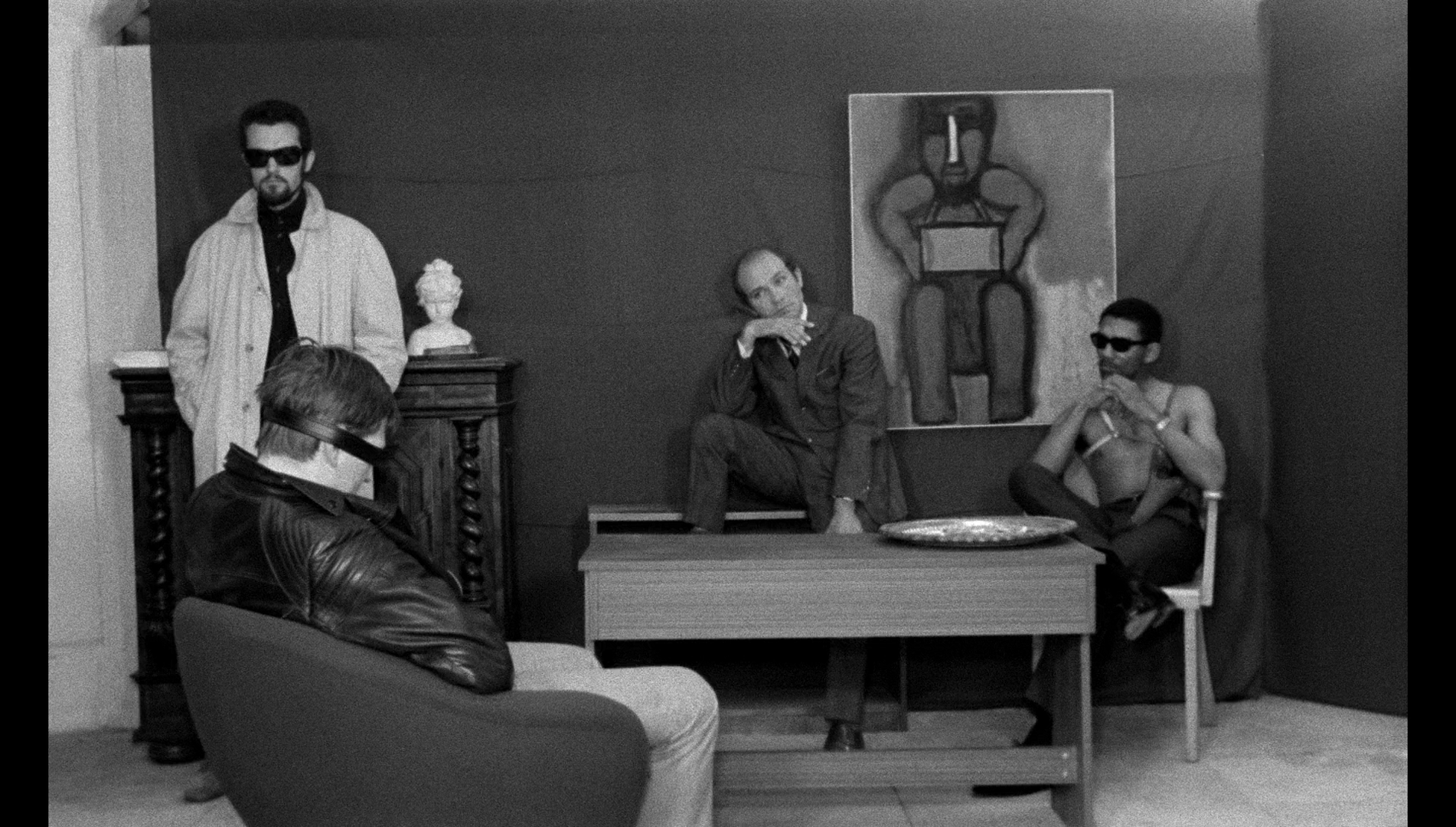

Love is Colder Than Death begins with petty crook Franz Walsch (played by Fassbinder) in captivity; he is being held in a bleak warehouse by a crime syndicate, a mixture of Germans and Americans, who attempt to persuade him to co-operate with them. Whilst he is held, alternately interrogated and beaten, Franz comes into contact with another criminal, Bruno (Ulli Lommel), who is being held by the syndicate for the same reason. Seeing a similarity between himself and the other man, Franz tells Bruno to contact him when he is released. Love is Colder Than Death begins with petty crook Franz Walsch (played by Fassbinder) in captivity; he is being held in a bleak warehouse by a crime syndicate, a mixture of Germans and Americans, who attempt to persuade him to co-operate with them. Whilst he is held, alternately interrogated and beaten, Franz comes into contact with another criminal, Bruno (Ulli Lommel), who is being held by the syndicate for the same reason. Seeing a similarity between himself and the other man, Franz tells Bruno to contact him when he is released.

When Bruno is freed, he heads on a train to the address in Munich that Franz gave to him. There, he meets Franz’s lover Joanna (Hanna Schygulla). Bruno, Franz and Joanna participate in a number of petty crimes together, eventually acquiring guns from a cobbler who doubles as a peddler in illegal firearms; the intention is to use these weapons in a heist. In a café, Franz confronts and kills a man who has been pursuing Franz with the intention of taking revenge for Franz’s murder of the man’s brother. Meanwhile, Bruno cold-bloodedly executes the only witness to the crime: a nineteen year old girl who is working as a waitress in the café. Later, Bruno also kills a policeman who asks to see Franz’s identity papers.

Franz is held by the police for the murder in the café. When he is released, Bruno proposes that the group split and join up again ‘when the heat is off’. However, matters become complicated when it seems that both Joanna and Bruno are intent on double-crossing one another (and, potentially, Franz).

In its cold, brittle pastiche of Hollywood gangster films, Love is Colder Than Death has often invited comparisons with French nouvelle vague-era pastiches of American gangster pictures – such as Jean-Luc Godard’s A bout de souffle (Breathless, 1959), Francois Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste (Shoot the Pianist, 1960) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le deuxieme souffle (1966) and Le samourai (1967). Ulrike Sieglohr suggests that Love is Colder Than Death ‘is a double homage to Hollywood gangster films as refracted through the sensibilities of the French New Wave: in other words, it is an imitation of an imitation’ (Siglohr, 2014: 17). However, Wheeler Winston Dixon and Gwendolyn Foster have argued that though ‘where Godard and Truffaut seem to be drunk with the plastic and kinetic possibilities of cinema, Fassbinder staged his scenes in long, flat takes, with the characters speaking in equally disengaged fashion, and editing reduced to a minimum’ (Dixon & Foster, 2008: 303-4). For instance, mid-way through the film we are presented with a very long reverse tracking shot which might remind viewers of Stanley Kubrick’s love of the tracking shot or the opening sequence of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1957). Another highly reflexive use of the camera takes place when Franz is questioned by the police over the murder of the man in the café, and as the detective paces to and fro in the room in which Franz is being interviewed, the camera follows the detective’s movements, shooting him side-on and following him on a dolly. Shortly afterwards, in what is perhaps the film’s most memorable scene, whilst Franz is being held by the police Bruno and Joanna visit a new, modern supermarket. In an extremely long single take, the camera tracks them as they move up and down the aisles, browsing the merchandise (and stealing a fair bit of it too); a cacophonic parody of supermarket ‘muzak’ accompanies them on the audio track. It’s a bizarre, satirical depiction of modern domesticity. In its cold, brittle pastiche of Hollywood gangster films, Love is Colder Than Death has often invited comparisons with French nouvelle vague-era pastiches of American gangster pictures – such as Jean-Luc Godard’s A bout de souffle (Breathless, 1959), Francois Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste (Shoot the Pianist, 1960) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le deuxieme souffle (1966) and Le samourai (1967). Ulrike Sieglohr suggests that Love is Colder Than Death ‘is a double homage to Hollywood gangster films as refracted through the sensibilities of the French New Wave: in other words, it is an imitation of an imitation’ (Siglohr, 2014: 17). However, Wheeler Winston Dixon and Gwendolyn Foster have argued that though ‘where Godard and Truffaut seem to be drunk with the plastic and kinetic possibilities of cinema, Fassbinder staged his scenes in long, flat takes, with the characters speaking in equally disengaged fashion, and editing reduced to a minimum’ (Dixon & Foster, 2008: 303-4). For instance, mid-way through the film we are presented with a very long reverse tracking shot which might remind viewers of Stanley Kubrick’s love of the tracking shot or the opening sequence of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1957). Another highly reflexive use of the camera takes place when Franz is questioned by the police over the murder of the man in the café, and as the detective paces to and fro in the room in which Franz is being interviewed, the camera follows the detective’s movements, shooting him side-on and following him on a dolly. Shortly afterwards, in what is perhaps the film’s most memorable scene, whilst Franz is being held by the police Bruno and Joanna visit a new, modern supermarket. In an extremely long single take, the camera tracks them as they move up and down the aisles, browsing the merchandise (and stealing a fair bit of it too); a cacophonic parody of supermarket ‘muzak’ accompanies them on the audio track. It’s a bizarre, satirical depiction of modern domesticity.

A highly allusive film, Love is Colder Than Death begins with an opening dedication to ‘Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jean-Marie Straub, Lino and Cuncho’ – the latter two names apparently referencing the protagonists (played by Lou Castel and Gian Maria Volonte) in Damiano Damiani’s political western all’italiana Quien sabe? (A Bullet for the General, 1966). The narrative evokes the Hollywood gangster film but Fassbinder’s style (his use of long, static takes and head-on compositions) challenge the grammatical conventions of Hollywood genre films. Fassbinder once noted that ‘I don’t make films about gangsters, but about people who have seen a lot of gangster films’ (Fassbinder, quoted in Elsaesser, 1996: 49). The allusions flow thick and fast at some points, reminding the viewer of the films of Jean-Luc Godard in the namedropping of film titles. After arriving in Munich and throwing in his lot with Franz and Joanna, Bruno goes with them to a department store where he tries on a pair of steel-rimmed sunglasses. Franz arrives and distracts the girl on the counter whilst Bruno steals the glasses by asking her, ‘I’m looking for round glasses, like the cop in Psycho had – the guy who finds Janet Leigh’s car’. A highly allusive film, Love is Colder Than Death begins with an opening dedication to ‘Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jean-Marie Straub, Lino and Cuncho’ – the latter two names apparently referencing the protagonists (played by Lou Castel and Gian Maria Volonte) in Damiano Damiani’s political western all’italiana Quien sabe? (A Bullet for the General, 1966). The narrative evokes the Hollywood gangster film but Fassbinder’s style (his use of long, static takes and head-on compositions) challenge the grammatical conventions of Hollywood genre films. Fassbinder once noted that ‘I don’t make films about gangsters, but about people who have seen a lot of gangster films’ (Fassbinder, quoted in Elsaesser, 1996: 49). The allusions flow thick and fast at some points, reminding the viewer of the films of Jean-Luc Godard in the namedropping of film titles. After arriving in Munich and throwing in his lot with Franz and Joanna, Bruno goes with them to a department store where he tries on a pair of steel-rimmed sunglasses. Franz arrives and distracts the girl on the counter whilst Bruno steals the glasses by asking her, ‘I’m looking for round glasses, like the cop in Psycho had – the guy who finds Janet Leigh’s car’.

Franz has a fiercely independent streak which is evidenced from the opening sequences of the film and marks the character with the brand of the outsider with whom Fassbinder’s subsequent films would be fascinated. ‘The syndicate wants you to work for us’, one of Franz’s captors tells him at the start of the film, ‘The syndicate gets what it wants. You know that’. ‘I work for myself and no-one else’, Franz insists in response to this. However, he decides to work with Bruno, and the two quickly form a close bond: Bruno’s laconic nature and his willingness to commit cold-blooded murder (for example, executing the young woman who witnesses Franz’s assassination of his pursuer in the café) offers a counterpoint to the more talkative Franz – the dynamic between the two is very similar to the dynamic between Lou Castel and Gian Maria Volonte’s respective characters in Damiani’s aforementioned Quien sabe? As in that film, in which Castel’s gringo disrupts Volonte’s relationship with his lover (played by Martine Beswick) after Castel associates himself with Volonte’s group of rebels during the Mexican Revolution, in Love is Colder Than Death Bruno’s presence disrupts Franz and Joanna’s relationship. At one point, Bruno kisses Joanna; Joanna responds by laughing at Bruno. Franz slaps her ‘Because you laughed at Bruno and Bruno is my friend’. ‘And me?’, Joanna asks. ‘You?’, Franz replies, ‘you love me anyway’.

Katzelmacher focuses on a group of Bavarian youngsters: Helga (Lilith Ungerer) and Paul (Rudolf Waldemar Brem), Marie (Hanna Schygulla) and Erich (Hans Hirschmuller), Rosy (Elga Sorbas) and Franz (Harry Baer), and Elisabeth (Irm Hermann) and Peter (Peter Moland). These young people live lives dominated by ennui, gathering at a café or simply ‘hanging out’ outside the apartment building in which they live. Their relationships are complex and corrupted by money: Rosy, for example, prostitutes herself to Franz, and Elisabeth mocks Peter because he is financially dependent upon her. Katzelmacher focuses on a group of Bavarian youngsters: Helga (Lilith Ungerer) and Paul (Rudolf Waldemar Brem), Marie (Hanna Schygulla) and Erich (Hans Hirschmuller), Rosy (Elga Sorbas) and Franz (Harry Baer), and Elisabeth (Irm Hermann) and Peter (Peter Moland). These young people live lives dominated by ennui, gathering at a café or simply ‘hanging out’ outside the apartment building in which they live. Their relationships are complex and corrupted by money: Rosy, for example, prostitutes herself to Franz, and Elisabeth mocks Peter because he is financially dependent upon her.

Into this situation enters Jorgos (played by Fassbinder himself), a migrant worker from Greece. Initially, the young Bavarians find Jorgos’ presence slightly disturbing (‘It’s strange having someone like that here’), and his exotic nature intrigues some of the women. Rumours soon spread that Jorgos has sexually assaulted a young woman named Gunda (Doris Mattes). This escalates into a suggestion that Jorgos is a Communist, and climaxes in an act of violence against Jorgos that hints at Germany’s Fascist past.

Katzelmacher covers themes that Fassbinder would reiterate and deepen in his later picture Angst essen Seele auf (Fear Eats the Soul, 1974). Both films focus on migrant ‘guest’ workers (Gastarbeiter) who begin relationships with German women and face prejudice from those around them. Katzelmacher was shot in nine days during August of 1969, for approximately 80,000 DM, and was based on the play of the same title that Fassbinder wrote in 1968, which was influenced by the Bavarian folk plays of Marieluise Fleisser (to whom both play and film are dedicated). The film won nearly a million DM in prizes and its success ensured that Fassbinder ‘was increasingly able to attract government financing for all but the most personal and eccentric of his creative projects’ (Watson, 1969: 6).

The original stage play apparently ran for forty minutes; the film adaptation has a running time of almost ninety minutes (see Watson, op cit.: 79). In Fassbinder’s play, Jorgos was introduced in the first scene; in the film, Jorgos isn’t introduced until much later in the narrative – shifting the focus from Jorgos and his experiences onto how Jorgos’ appearance in the story disrupts the lives of the young Bavarians (ibid.). The original stage play apparently ran for forty minutes; the film adaptation has a running time of almost ninety minutes (see Watson, op cit.: 79). In Fassbinder’s play, Jorgos was introduced in the first scene; in the film, Jorgos isn’t introduced until much later in the narrative – shifting the focus from Jorgos and his experiences onto how Jorgos’ appearance in the story disrupts the lives of the young Bavarians (ibid.).

In reference to the plot of Katzelmacher, Fassbinder once said that ‘Marie belongs to Erich; Paul sleeps with Helga; Peter lets Elisabeth support him; and Rosy does it with Franz for the money’ (Fassbinder, quoted in Watson, op cit.: 80). The problems within these relationships are established well before the arrival of Jorgos: John Sandford has said that Jorgos is simply a ‘catalyst, unleashing the pent-up jealousies, rivalries, antagonisms, and frustrations of the milieu into which he enters’ (Sandford, quoted in ibid.). (Certainly, the critical literature often draws parallels between Katzelmacher and Pasolini’s Teorema/Theorem, 1968, in that both films feature a world into which a stranger intrudes, their appearance acting as a catalyst for radical changes in the behaviours of those whose lives they touch; see Patti, 2010.) Because of this, Jorgos ‘becomes a scapegoat, blamed and punished for problems he has not caused but merely made manifest’ (Sandford, quoted in ibid.).

Certainly, intimate relationships within the world depicted in Katzelmacher seem to be dominated by (patriarchal) violence and are often controlled and dictated by a capitalistic imperative: both Erich and Paul assault their ‘lovers’ (Marie and Helga, respectively), and both Rosy and Paul prostitute themselves to others (Rosy to various men, and Paul to the bourgeois businessman Klaus). Meanwhile, Elisabeth continually mocks Peter for his reliance on her money. Early in the film, two of the male friends talk about their relationships. ‘All we ever talk about is marriage’, one of them tells the other, in reference to his lover. ‘Punch her in the face’, his friend tells him, ‘Then she’ll shut up’. A much later conversation sees Paul revealing that Helga is pregnant and declaring that he ‘could have killed her’. ‘Punch her in the belly and throw her in the Isar’, Paul’s friend says, ‘Then the baby will go’. In another scene, Franz tells Rosy, after she has fucked him for money, that ‘You love me in your heart’. ‘That has nothing to do with money’, she responds, ‘Love and so on always have to do with money’, he tells her. Much later, towards the end of the film, Rosy is asked ‘What about love?’ She responds by saying, ‘Not for me. It makes you old’.

During the years of the Wirtschaftswunder (‘Economic Miracle’) of the 1950s and 1960s, Gastarbeiter were encouraged owing to a shortage of domestic labour. These Gastarbeiter would often be from southern Europe and also countries such as Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a perception that some of these Gastarbeiter were settling in Germany beyond the agreed period (usually one or two years), leading to a spiraling sense of resentment and antagonism. The film’s title, Katzelmacher is in reference to a slang term for such Gastarbeiter; the term ‘katzelmacher’ contains within it the connotation that the Gastarbeiter fuck (and breed) like tomcats. In the late 1960s Germany experienced its first economic slump since the Second World War, leading to an increased sense of resentment expressed towards the Gastarbeiter, who were seen as taking jobs from young Germans – something which is explored in Katzelmacher via the unemployed young Bavarians’ increasingly distrustful treatment of Jorgos. (By playing the role of Jorgos, Fassbinder underscores the identification with the outsider which runs throughout his body of work.) During the years of the Wirtschaftswunder (‘Economic Miracle’) of the 1950s and 1960s, Gastarbeiter were encouraged owing to a shortage of domestic labour. These Gastarbeiter would often be from southern Europe and also countries such as Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a perception that some of these Gastarbeiter were settling in Germany beyond the agreed period (usually one or two years), leading to a spiraling sense of resentment and antagonism. The film’s title, Katzelmacher is in reference to a slang term for such Gastarbeiter; the term ‘katzelmacher’ contains within it the connotation that the Gastarbeiter fuck (and breed) like tomcats. In the late 1960s Germany experienced its first economic slump since the Second World War, leading to an increased sense of resentment expressed towards the Gastarbeiter, who were seen as taking jobs from young Germans – something which is explored in Katzelmacher via the unemployed young Bavarians’ increasingly distrustful treatment of Jorgos. (By playing the role of Jorgos, Fassbinder underscores the identification with the outsider which runs throughout his body of work.)

In many ways, Katzelmacher feels like a dry run for Fear Eats the Soul. However, the later film arguably offers a richer, more profound examination of some of the themes outlined in Katzelmacher, owing to the fact that the Gastarbeiter in that picture is a Moroccan migrant worker, Ali (El Hedi ben Salem) in an era, following the events at the Olympic Village in Munich at the 1972 Olympic Games, in which prejudice against Arabs was rife. Like Ali in Fear Eats the Soul, Jorgos in Katelmacher speaks a form of ‘pidgin’ German (‘Girlfriend? Fuckety-fuck?’, Jorgos queries when asked about whether he has a lover back home); and as in Fear Eats the Soul, the Germans in Katzelmacher express their prejudice towards the Gastarbeiter largely through a preoccupation with his ‘exotic’ sexuality: one of the first hostile rumours that surrounds the Greek migrant is that he sexually assaulted one of the female members of the group of friends around which the film revolves. This soon escalates, with another of the women suggesting Jorgos forced himself upon her.

Despite Jorgos telling the young people that he’s working in Germany simply because although there is work back home in Greece, it is badly paid and the work in Germany pays much better, the friends become increasingly suspicious of the migrant worker; the accusations progress from suggestions that he sexually assaulted Gunda – and then another of the women – to the spreading of a rumour that Jorgos is a Communist (because ‘Where he comes from they have Communists […] I read it in the paper. Lots of Communists’). ‘He’s one of them [a Communist], and he comes here’, one of the friends asserts. The rumours about Jorgos are assumed to be true (‘If everyone’s talking about it, there must be something to it’, a character asserts). Following the climactic assault on Jorgos, an act which carries with it the weight of Germany’s Fascist past, the Bavarians attempt to divest themselves of any responsibility for the cruel beating Jorgos receives. ‘It had to happen’, one of them says, ‘He was walking around as if he belonged there’. Despite Jorgos telling the young people that he’s working in Germany simply because although there is work back home in Greece, it is badly paid and the work in Germany pays much better, the friends become increasingly suspicious of the migrant worker; the accusations progress from suggestions that he sexually assaulted Gunda – and then another of the women – to the spreading of a rumour that Jorgos is a Communist (because ‘Where he comes from they have Communists […] I read it in the paper. Lots of Communists’). ‘He’s one of them [a Communist], and he comes here’, one of the friends asserts. The rumours about Jorgos are assumed to be true (‘If everyone’s talking about it, there must be something to it’, a character asserts). Following the climactic assault on Jorgos, an act which carries with it the weight of Germany’s Fascist past, the Bavarians attempt to divest themselves of any responsibility for the cruel beating Jorgos receives. ‘It had to happen’, one of them says, ‘He was walking around as if he belonged there’.

Wallace Steadman Watson argues that Katzelmacher is connected to Love is Colder Than Death via its focus on a group of young people, and that Katzelmacher ‘portrays the inarticulate despair’ of these ‘young suburban Bavarians’ whose frustrations are ‘taken out’ on Jorgos (Watson, 1969: 3). The young people in this film seem afflicted by a profound sense of ennui, Wim Wenders commenting on the film’s release that the picture was ‘lifeless’ and ‘gruesome’, with ‘the characters acting like marionettes in a photo-novel with black bands over their eyes’ (Wenders, cited in ibid.: 81). Thomas Elsaesser has argued that Katzelmacher ‘is the most experimental of his [Fassbinder’s] early works’, demonstrating ‘formal purity’ and ‘calculated coldness’ (Elsaesser, 1996: 270).

The film’s dialogue is delivered in a very stilted, Brechtian fashion, emphasising the cold, disconnected relationships that exist between the characters; meanwhile, the photography is dominated by static ‘head-on’ compositions, presented via long takes, in which the characters sit around, often facing away from one another, and failing to communicate. These tableau-like compositions are repeated throughout the film, the same locations being used over and over to reinforce the lack of communication within them – the area outside the café, the inside of the café, the railing against which the characters lounge outside their apartment building, Helga’s bedroom, Rosy’s living room, the kitchenette of Elisabeth’s home. In one scene, the group of male friends are introduced to Klaus (unaware that Paul is prostituting himself to Klaus). They stand around outside the apartment building, none of them speaking or engaging with any of the others; Klaus stands in the foreground, awkwardly. After a while, with no conversation having taken place, Klaus simply asserts, ‘Oh, well. I must be going’, and he walks offscreen. The incident underscores the intense self-involvement exhibited by these young people. Perhaps the most astute line of dialogue comes towards the end of the picture, when one of the characters observes, ‘How do we know what’s normal?’ However, this is answered at the end of the picture by the declaration made by one of the group of friends that ‘We belong here and no-one else’. The film’s dialogue is delivered in a very stilted, Brechtian fashion, emphasising the cold, disconnected relationships that exist between the characters; meanwhile, the photography is dominated by static ‘head-on’ compositions, presented via long takes, in which the characters sit around, often facing away from one another, and failing to communicate. These tableau-like compositions are repeated throughout the film, the same locations being used over and over to reinforce the lack of communication within them – the area outside the café, the inside of the café, the railing against which the characters lounge outside their apartment building, Helga’s bedroom, Rosy’s living room, the kitchenette of Elisabeth’s home. In one scene, the group of male friends are introduced to Klaus (unaware that Paul is prostituting himself to Klaus). They stand around outside the apartment building, none of them speaking or engaging with any of the others; Klaus stands in the foreground, awkwardly. After a while, with no conversation having taken place, Klaus simply asserts, ‘Oh, well. I must be going’, and he walks offscreen. The incident underscores the intense self-involvement exhibited by these young people. Perhaps the most astute line of dialogue comes towards the end of the picture, when one of the characters observes, ‘How do we know what’s normal?’ However, this is answered at the end of the picture by the declaration made by one of the group of friends that ‘We belong here and no-one else’.

Video

The two feature films have been restored, and the presentations are based on 4k scans of the films’ original negatives. All of the contents of this release are housed on a single double-layered Blu-ray disc. The two features take up a little over 20Gb of space each. Both features are uncut: Love is Colder Than Death running for 88:39 mins, and Katzelmacher running for 89:24 mins. Both features are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The two feature films have been restored, and the presentations are based on 4k scans of the films’ original negatives. All of the contents of this release are housed on a single double-layered Blu-ray disc. The two features take up a little over 20Gb of space each. Both features are uncut: Love is Colder Than Death running for 88:39 mins, and Katzelmacher running for 89:24 mins. Both features are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

Love is Colder Than Death is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1; Katzelmacher is presented in its original screen ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome photography of both features fares superbly in these new restorations. As noted above, both features feature in their photography beautiful, stark compositions which are almost painterly in their construction. The image is crisp and detailed throughout, and in the case of both films contrast levels are extremely well-balanced, offering strong, clearly-defined mid-tones and rich blacks. Solid encodes ensure that the presentations retain the natural structure of 35mm film. The grain in Katzelmacher seems coarser than that in Love is Colder Than Death, which may be a product of different film stocks. Additionally, Katzelmacher features a very small handful of shots that seem to be patched in from an inferior source (this is noticeable because these shots feature slightly ‘blown’ contrast and flatter mid-tones), perhaps owing to damage to the original film materials.

NB. Some large screengrabs from the two main features are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Both films feature LPCM 1.0 mono tracks. Katzelmacher’s dialogue is wholly in German; Love is Colder Than Death is mostly in German with a few lines in English. These audio tracks, in the case of both feature films, are clean and clear throughout, and whilst by no means ‘showy’, they demonstrate a good sense of depth and range. Optional English subtitles are provided for both films. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows: The disc contents are as follows:

- Love is Colder Than Death (88:39).

- Katzelmacher (89:24).

- ‘The City Tramp’ (11:56). This 1966 short film by Fassbinder focuses on a tramp (Christoph Roser) who, whilst wandering the streets of Munich, discovers a gun lying in the gutter. He tries to dispose of it in a park, but the weapon is returned to him by a waitress. The tramp fantasises about using the gun to commit suicide. In the park, two young men take the gun from the tramp and taunt him with it. He falls to the ground; the men wander off, and the tramp raises his hand and, using it to mimic the gun he has lost, ‘shoots’ the two young men as they recede into the distance.

The film is notable for its fatalistic worldview and its focus on the type of outsider who would come to define Fassbinder’s feature films. The title may seem to allude to Chaplin’s ‘little tramp’, but in truth the main character here has more in common with Vladimir and Estragon from Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot.

- ‘The Little Chaos’ (9:45). Also made in 1966, this short film directed by Fassbinder focuses on three young people (Fassbinder, Christoph Roser and Marite Greiselis) who sell magazines door-to-door. They are comically unsuccessful in their endeavours. Fassbinder’s character announces ‘I’d like to see a gangster movie that ends well, for once’, and the trio break into the apartment of a middle-aged woman, holding her hostage. They play Wagner on the woman’s record player, and Fassbinder asks her ‘Do you love the Fuhrer?’ before tormenting and humiliating the woman. They steal money from her. Fassbinder asks what the others are going to do with their share before announcing, ‘Me? I’m going to the pictures’.

In its focus on the three young people, its photography and its jazzy score, ‘The Little Chaos’ feels heavily influenced by Godard, and especially Bande à part (1964). The film introduces Fassbinder’s off-kilter look at crime, which the director would expand upon in Love is Colder Than Death and the later Der amerikanische Soldat (The American Soldier, 1970). Both this film and ‘The City Tramp’ are in German, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘End of the Commune’ (49:18). Made in 1970, ‘Ende einer Kommune?’ (or ‘End of the Commune’) is a documentary directed by Joachim von Mengershausen about Fassbinder’s anti-teater group. It includes some behind-the-scenes footage from the rehearsing of Love is Colder Than Death and also rehearsals for Fassbinder’s play The Coffeehouse. There’s also some fascinating footage from the exhibition of Love is Colder Than Death at the Berlin Film Festival, which underscores how hostile some audiences were to that picture when it was first released. This is in German, with optional English subtitles.

- Interview with Ulli Lommel (10:01). Lommel here reflects on Love is Colder Than Death, in which he starred as the enigmatic Bruno. He suggests that he was hesitant about working on the film when Fassbinder revealed, during Lommel’s first day on set, that the crew consisted of one other person and the actors were asked to chip in and perform various other jobs. However, Lommel felt that he had no choice. He also reveals that Fassbinder demanded that Lommel sell his car, a beautiful MG, to fund the film when the production ran out of film. Lommel suggests that he was ‘hypnotised’ by Fassbinder somehow and agreed to this, becoming a producer on the film. He discusses the hostile response from then film’s first audiences and Fassbinder’s insistence, in response to this, that he would continue to make films. ‘He just ignored all these negative remarks and people laughing about him’, Lommel says. Lommel speaks in English.

- Katzelmacher trailer (3:14).

Overall

Previously available as part of Arrow’s boxed set release of a number of Fassbinder pictures, this standalone release of Fassbinder’s first two feature films, along with the two short films included on this disc, is a must-buy for fans of the director. Newcomers to Fassbinder would do well to note that the two films here, like the other pictures Fassbinder made between during his anti-teater days, differ in many ways from the Douglas Sirk-esque melodramas he made post-1971, Love is Colder Than Death and Katzelmacher contain within them Fassbinder’s defining fascination with the outsider and the examination of issues of identity and sexuality that would come to define his later works too. (As noted above, Katzelmacher in particular finds its themes reiterated in a later Fassbinder picture, the acclaimed Fear Eats the Soul.) The presentations of the feature films, and the shorts too, are excellent, and this release comes with a very strong recommendation. Previously available as part of Arrow’s boxed set release of a number of Fassbinder pictures, this standalone release of Fassbinder’s first two feature films, along with the two short films included on this disc, is a must-buy for fans of the director. Newcomers to Fassbinder would do well to note that the two films here, like the other pictures Fassbinder made between during his anti-teater days, differ in many ways from the Douglas Sirk-esque melodramas he made post-1971, Love is Colder Than Death and Katzelmacher contain within them Fassbinder’s defining fascination with the outsider and the examination of issues of identity and sexuality that would come to define his later works too. (As noted above, Katzelmacher in particular finds its themes reiterated in a later Fassbinder picture, the acclaimed Fear Eats the Soul.) The presentations of the feature films, and the shorts too, are excellent, and this release comes with a very strong recommendation.

References:

Dixon, Wheeler Winston & Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey, 2008: A Short History of Film. Rutgers University Press

Elsaesser, Thomas, 1996: Fassbinder’s Germany: History, Identity, Subject. Amsterdam University Press

Patti, Emanuela, 2010: ‘Fictional Reality and Real Fiction in Pasolini and Fassbinder’. In: Vighi, Fabio & Nouss, Alexis (ed), 2010: Pasolini, Fassbinder and Europe. Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 37-48

Rheuban, Joyce, 1986: ‘Introduction’. In: Rheuban, Joyce (ed), 1986: The Marriage of Maria Braun: Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Director. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press: 1-30

Sieglohr, Ulrike, 2014: Hanna Schygulla. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Watson, Wallace Steadman, 1996: Understanding Rainer Werner Fassbinder: Film and Private and Public Art. University of South Carolina Press

Love is Colder Than Death

Katzelmacher

|