|

The Film

Eyewitness (Peter Yates, 1981) Eyewitness (Peter Yates, 1981)

Peter Yates’ Eyewitness (1981) is a neo-noir in a very different mould to the same year’s smoldering Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) – though both pictures share the casting in the lead male role of William Hurt, who in many ways, at least in these two pictures, arguably embodies the traits associated with the actors allied with classic films noir. Where Body Heat has come to define the association of neo-noir with an increased sense of eroticism (in the manner also exhibited in Bob Rafelson’s remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice, likewise released in 1981, or later films such as the Wachowskis’ Bound, 1995), Eyewitness looked instead to pictures like Ted Tetzlaff’s The Window (1949) or Roy Rowland’s Witness to Murder (1954) for inspiration: paranoid films noir about an often downtrodden and disbelieved protagonist who witnesses a crime and finds him/herself caught up in a criminal conspiracy which threatens her/his life. As such, there are some similarities between the picture and Brian De Palma’s Blow Out, another thriller released in 1981. (This mode within film noir also found a similar expression in European thrillers of the 1970s - in particular, examples of the thrilling all’italiana such as Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo/The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970.) Like many of the classic American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s, whose downbeat themes were filtered through a lens shaded by the cultural impact of the war, Eyewitness features a downtrodden war veteran as its protagonist – though here, the anti-hero of the piece, janitor Darryl Deever (played by William Hurt), is a veteran of the war in Vietnam rather than the Second World War.

Deever is introduced as a janitor in an office building. Working the night shift, Deever approaches Vietnamese businessman Mr Long (Chao Li Chi), who rents rooms in the building, in an attempt to get Deever’s friend Aldo Mercer (James Woods) his job back: Mercer also worked as a janitor in the same building, until a disagreement with Mr Long led to Mercer being fired. Having served together as Marines during the war in Vietnam, Deever and Mercer are lifelong friends, and Deever is in fact engaged to Mercer’s sister Linda (Pamela Reed). Deever is introduced as a janitor in an office building. Working the night shift, Deever approaches Vietnamese businessman Mr Long (Chao Li Chi), who rents rooms in the building, in an attempt to get Deever’s friend Aldo Mercer (James Woods) his job back: Mercer also worked as a janitor in the same building, until a disagreement with Mr Long led to Mercer being fired. Having served together as Marines during the war in Vietnam, Deever and Mercer are lifelong friends, and Deever is in fact engaged to Mercer’s sister Linda (Pamela Reed).

However, Deever is mildly obsessed with pretty television news reporter Antonia ‘Tony’ Sokolow (Sigourney Weaver), watching her news broadcasts every evening. For her part, Tony is in a relationship with Joseph (Christopher Plummer), a Jewish activist responsible for helping persecuted Jews reach American shores.

One night, whilst at work, Deever hears a commotion in Long’s office. Investigating, he finds Long dead: the Vietnamese businessman has been murdered. Deever is questioned by two detectives, Lieutenants Black (Morgan Freeman) and Jacobs (Steven Hill). Afterwards, Deever spots Tony in the lobby of the hotel, and pretends to have information relating to the case so as to have an excuse to talk to her. He leads her along, suggesting that if she will see him again, he will reveal to her what he knows about the murder – thus giving her an exclusive interview with the only eyewitness to the crime.

When Tony is accosted by two associates of Long’s, who attempt to bundle her in the back of a car, Deever rescues her. He takes her back to his apartment, where he tends to her wounds. The pair make love, unaware that outside the building, Aldo and Joseph wait – both of them aware of the burgeoning relationship between Tony and Deever. Subsequently, Deever breaks off his engagement with Linda – much to Linda’s relief, in fact. This upsets Aldo, who wished for his sister to marry Deever, giving Aldo a family that he could experience vicariously.

When Deever’s pet dog Ralph attacks its owner upon Deever’s return to his apartment, it seems that Deever’s desire to exploit and overplay his role as eyewitness to Long’s murder, for the purposes of initiating a relationship with Tony, appears to have born bitter fruit. Concluding that he has been targeted because ‘he [Long’s killer] thought I knew more than I did’, Deever finds himself caught in the crossfire of a murderer who wishes to cover his tracks. When Deever’s pet dog Ralph attacks its owner upon Deever’s return to his apartment, it seems that Deever’s desire to exploit and overplay his role as eyewitness to Long’s murder, for the purposes of initiating a relationship with Tony, appears to have born bitter fruit. Concluding that he has been targeted because ‘he [Long’s killer] thought I knew more than I did’, Deever finds himself caught in the crossfire of a murderer who wishes to cover his tracks.

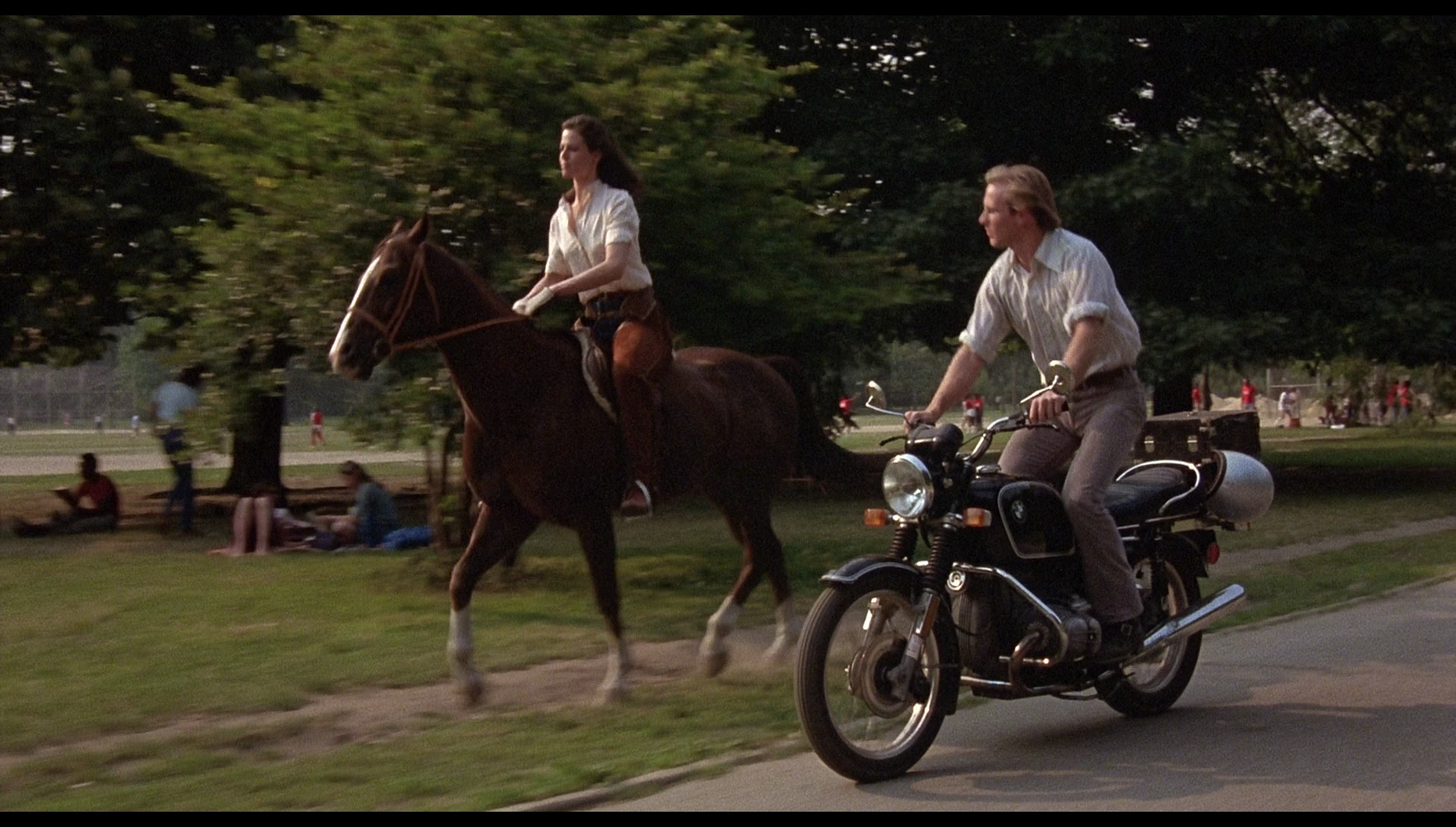

Deever’s relationship with Tony is characterised by Deever’s clumsy attempts to flirt with the news anchor, which for some of the film’s running time at least makes him seem more like a socially awkward stalker than a prospective suitor: meeting her for the first time, Deever tells her, ‘I have had a crush on you for about two years. I haven’t been unfaithful to you. But I doubt that you’ve been faithful to me. All that can change’. Later in the film, he attempts to seduce Tony by equating his janitorial expertise at buffing floors with sexual prowess: ‘Say, do your floors need buffing or something?’, he asks Tony, ‘I’m real good, a pro. First, I strip the old wax, then I lay down an even coat. I buff it, and I buff it. Gently. Slowly. Till it beams’. (Come to think of it, this is the only film I can recollect in which the practice of buffing floors has been used as a metaphor for sex.) When Tony tells Deever that she spends her Thursdays horseriding through Central Park, he endeavours to meet her there on his motorcycle, attempting to match her horse’s movements with his bike. Deever displays an amazing ability to settle Tony’s horse, and his way with animals begins to win her over: ‘Animals and kids adore me’, Deever tells her, ‘That just leaves the rest of the world’. When Deever rescues Tony from Long’s associated, taking her back to his apartment where he treats her wounds, the pair make love. Outside the apartment building, unaware of one another’s identities, Joseph and Aldo wait, gazing up at the windows of Deever’s apartment – both of them motivated by jealousy of one kind or another. (Joseph is of course jealous that his fiancée is in bed with another man, whilst Aldo is distraught that his prospective brother-in-law is cheating on Linda, thus potentially destroying Aldo’s dream of living vicariously through his sister’s experience of family life: ‘I wanted, like, a family’, Aldo later tells Deever when Deever reveals that he and Linda have cancelled their engagement.)

Things aren’t what they seem to be. Deever must negotiate his relationship with Mercer, clearly doubting Mercer’s story and believing Mercer to be the killer of Long – whilst the audience may be considering Deever as a potential suspect in the murder around which the narrative pivots. This sense of ‘wrongfooting’ the audience in terms of the relationships between characters is signaled in an early scene in the picture, before Long has been killed, in which Deever returns home after his shift at work and is attacked by a dog – before the film reveals that the dog is in fact Deever’s pet, Ralph, and the scenario is simply part of a ‘game’ that Deever and Ralph play whenever Deever returns to his apartment after work. Things aren’t what they seem to be. Deever must negotiate his relationship with Mercer, clearly doubting Mercer’s story and believing Mercer to be the killer of Long – whilst the audience may be considering Deever as a potential suspect in the murder around which the narrative pivots. This sense of ‘wrongfooting’ the audience in terms of the relationships between characters is signaled in an early scene in the picture, before Long has been killed, in which Deever returns home after his shift at work and is attacked by a dog – before the film reveals that the dog is in fact Deever’s pet, Ralph, and the scenario is simply part of a ‘game’ that Deever and Ralph play whenever Deever returns to his apartment after work.

Also known as The Janitor, the title under which it played in Britain, Eyewitness marked the second collaboration between director Peter Yates and writer Steve Tesich, following 1979’s Breaking Away. Like many roughly contemporaneous pictures (most obviously, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, 1978), Eyewitness explores the cultural fallout from the war in Vietnam. Mr Long’s reputation as a shady dealer in information can be traced back to the war in Vietnam. When Black and Jacobs question Deever over his discovery of Long’s body, Deever tells them that during Vietnam ‘Both sides thought he [Long] was working for them. He bought and sold everything, including information, and got paid by everybody involved’. When Jacobs suggests that ‘If that were true, you’d have a grudge a mile long’, Deever establishes his difference from Aldo by asserting ‘That [Vietnam] wasn’t my country, was it?’ From the outset, Aldo demonstrates a profound sense of xenophobia. Both he and Deever served as Marines during the war in Vietnam, but Deever has managed to separate his experiences during that war from his present circumstances as, essentially, a servant to Long. Where Deever has left the war, and the cultural conflicts embodied with it, in the past, Aldo has committed himself to carrying these with him, his barely concealed bitterness expressing itself through racist outbursts. ‘Slant-eyed little mother…’, Aldo asserts in reference to Mr Long, ‘Well, I tell you, man, it’s some country we’re living in: getting fired over a gook like that’. He continues, telling Deever, ‘Two years in Vietnam. We clean up; we mop up after them [the Vietnamese]. We come back to our own fucking country and they’re here again’. ‘That’s just the way it is’, Deever responds philosophically. Aldo’s prejudices come to the foreground again, later in the film, when he and Deever are introduced separately to Lieutenant Black. Speaking with Deever, Black introduces himself as Lieutenant Black before joking dryly, in reference to his ethnicity, ‘That should be easy to remember’. However, when Black introduces himself to Aldo, Aldo quips anxiously, ‘That should be easy enough to remember’ – his echoing of the words Lieutenant Black spoke to Deever underscoring the extent to which, whereas Deever is blind or disinterested in ethnic difference, for Aldo ethnic difference is at the forefront of his mind. Black reacts subtly to this, suggesting that he has developed a habit of using the revelation of his name as a Litmus test for his suspects’ attitudes towards issues of ethnicity.

However, for the most part Deever is absolutely certain that Aldo didn’t kill Long: ‘Aldo couldn’t kill anybody’, he says at one point, ‘Even in the war, he couldn’t do it’. Shortly afterwards, Black and Jacobs discuss Aldo’s war record and his reputation for cowardice, which led to him being court-martialed: ‘They didn’t want cowards in that war’, Black says. Jacobs asks Black why he’s so sure Aldo murdered Long: ‘Why does a weird coward [like Aldo] make a good suspect?’, Jacobs queries. ‘A hero’s got nothing to prove’, Black responds, ‘Deever’s a decorated hero’. ‘Whoever killed Long is a hero in my book’, Jacobs asserts, referencing Long’s reputation as a double agent and dealer in information to both sides, ‘My son died in that war – my good son’. When, after a period of doubt, Deever finally comes round to the awareness that Aldo didn’t kill Long, Aldo tells Deever that it wasn’t so much his status as a coward that hurt him, but how he was regarded by Deever: ‘I was always such a coward, Aldo asserts in reference to the murder of Long, Everybody knows I was a coward, so… But it was you knowing it that hurt me [….] I wish I had killed that bastard. So help me, I wish I had done it’. However, for the most part Deever is absolutely certain that Aldo didn’t kill Long: ‘Aldo couldn’t kill anybody’, he says at one point, ‘Even in the war, he couldn’t do it’. Shortly afterwards, Black and Jacobs discuss Aldo’s war record and his reputation for cowardice, which led to him being court-martialed: ‘They didn’t want cowards in that war’, Black says. Jacobs asks Black why he’s so sure Aldo murdered Long: ‘Why does a weird coward [like Aldo] make a good suspect?’, Jacobs queries. ‘A hero’s got nothing to prove’, Black responds, ‘Deever’s a decorated hero’. ‘Whoever killed Long is a hero in my book’, Jacobs asserts, referencing Long’s reputation as a double agent and dealer in information to both sides, ‘My son died in that war – my good son’. When, after a period of doubt, Deever finally comes round to the awareness that Aldo didn’t kill Long, Aldo tells Deever that it wasn’t so much his status as a coward that hurt him, but how he was regarded by Deever: ‘I was always such a coward, Aldo asserts in reference to the murder of Long, Everybody knows I was a coward, so… But it was you knowing it that hurt me [….] I wish I had killed that bastard. So help me, I wish I had done it’.

There are hints, sadly underdeveloped in the film, that Joseph suffers from an existential dilemma. Early in the film, as Tony drives him to the airport, he tells her solemnly, ‘Shame, huh, for two smart people like you and me to never know what it’s like to run away’. Later in the picture, he is led to question the violence that his ideological position has encouraged him to adopt, and reacts badly to this. He is committed to helping persecuted Jews escape to America – regardless of the actions necessitated by his commitment to this ideal. As Tony’s parents remind Joseph, Long may have been a double-dealing extortionist, but Deever is an innocent man – whose only ‘transgression’ is that he may be able to solve the mystery of how murdered Long. As Joseph himself says, ‘I would almost prefer another war to this kind of peace. The lines were drawn clearer then’. Through the focus on Jewish culture, which is the issue at the heart of the enigma surrounding the murder of Long, Eyewitness explores the concept of the diaspora. Early in the film, Joseph addresses the people who have gathered for a ‘fundraiser’ for Jewish refugees. ‘Unfortunately’, Joseph asserts, ‘money today buys freedom. And as long as there are Jews who are held in bondage, and as long as we can do something about it, we cannot stop. It is the irony of our time that we, a people without a country for so long, have come to have so many countries. Russia gave us light, America gave us hope, and Israel gave us a reason to live’.

Video

Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, this 1080p presentation of Eyewitness uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Upon playing the film, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the picture as Eyewitness or The Janitor; selecting one option or another doesn’t make a great deal of difference, only affecting the onscreen title the viewer sees during the main titles sequence. Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, this 1080p presentation of Eyewitness uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Upon playing the film, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the picture as Eyewitness or The Janitor; selecting one option or another doesn’t make a great deal of difference, only affecting the onscreen title the viewer sees during the main titles sequence.

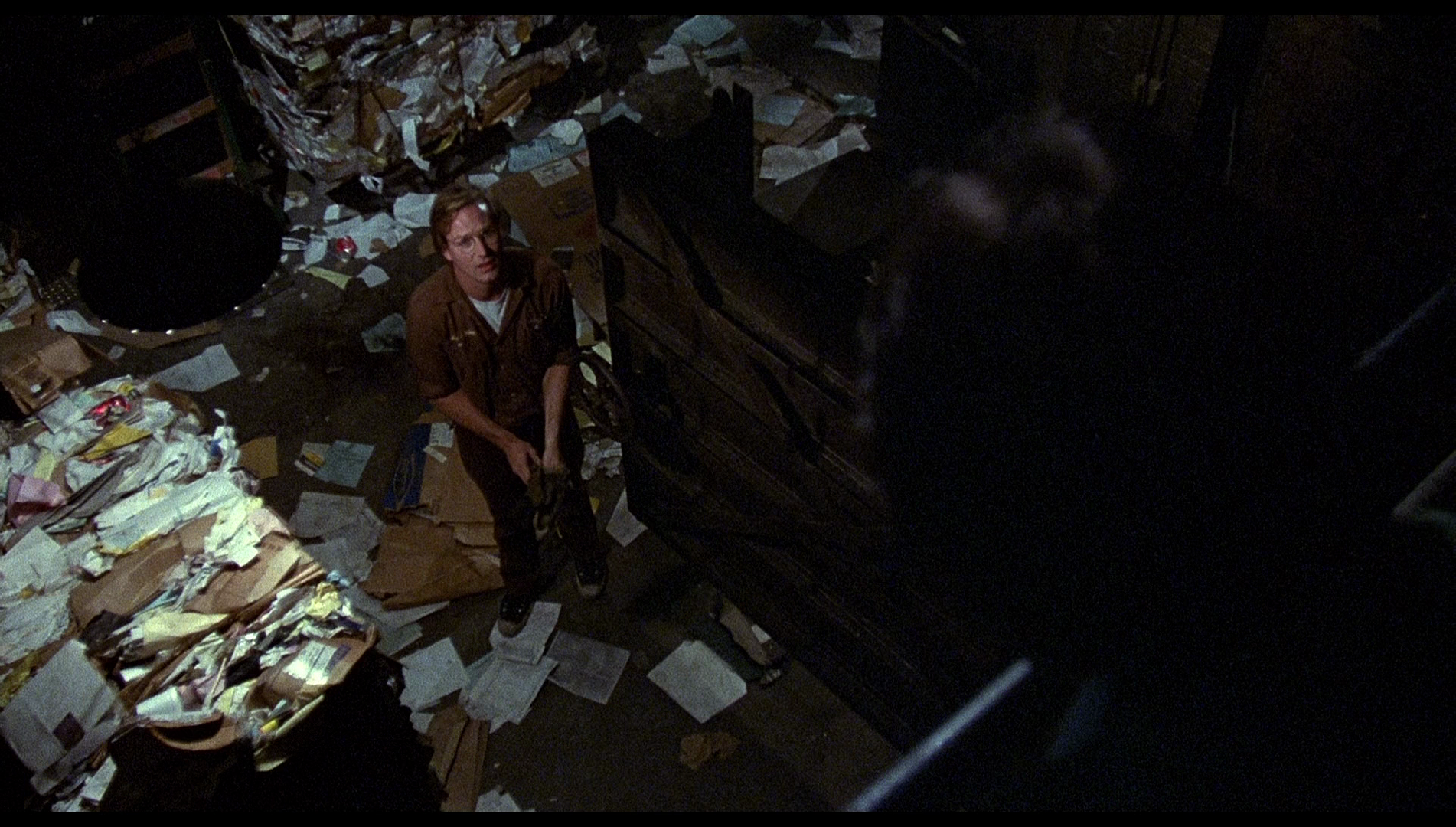

The colour 35mm photography is presented very nicely here. The production seems to have predominantly used shorter focal lengths, leaving most scenes staged in depth – even the majority of low light scenes. The strong depth of field within the original photography is carried over into a pleasing sense of depth in this Blu-ray presentation. The image is clean and clear throughout, with an impressive level of detail on display. Contrast levels are superb, offering a careful balance of light and dark with defined midtones: this works to the film’s benefit, given the number of low light sequences the picture contains. Finally, an excellent encode ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, even in scenes with particle effects (see the first of the large screengrabs at the bottom of this review, for instance).

The film is uncut and runs for 102:08 mins.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, which is clear throughout and demonstrates excellent range. This is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, which are easy to read and free of any issues.

Extras

The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Peter Yates and critic Marcus Hearn. Hearn and Yates talk about the titling of the film, with Hearn noting that the UK title ‘The Janitor’ is ‘ironic considering “janitor” is an American word’. Yates reveals that the original title was The Janitor Can’t Dance, which was considered too convoluted by the American distributors – hence the changing of the title to Eyewitness. (Yates’ preferred title was, apparently, The Janitor.) The pair discuss the themes of the picture, and Yates discusses his approach to filming violence, and Yates reflects on shooting in New York – and the cultural significance of the city. - An audio commentary with Peter Yates and critic Marcus Hearn. Hearn and Yates talk about the titling of the film, with Hearn noting that the UK title ‘The Janitor’ is ‘ironic considering “janitor” is an American word’. Yates reveals that the original title was The Janitor Can’t Dance, which was considered too convoluted by the American distributors – hence the changing of the title to Eyewitness. (Yates’ preferred title was, apparently, The Janitor.) The pair discuss the themes of the picture, and Yates discusses his approach to filming violence, and Yates reflects on shooting in New York – and the cultural significance of the city.

- Peter Yates in Conversation with Derek Malcolm. This audio recording of Yates, speaking with Derek Malcolm in front of a live audience at the NFT in 1982, functions essentially as an audio commentary of sorts, being presented as audio accompaniment to the main feature. There’s much discussion of the car chases in Bullitt (1969) and Robbery (1967), and some illuminating and extensive discussion of Krull (1983) – which, at the time of the recording of the interview was of course Yates’ most recent picture. Yates spends some time discussing the differences between Hollywood and the British film industry.

- Peter Yates in Conversation with Quentin Faulk (78:01). Recorded in front of a live audience at the NFT in 1996, this conversation between Yates and Quentin Faulk focuses on Yates’ career generally. Yates reflects on his films, beginning with Bullitt (1969) and the shooting of the iconic car chase sequence in that picture. There’s some interesting discussion of Robbery (1967), which Faulk describes as Yates’ ‘breakthrough’ film inasmuch as the picture propelled Yates into his Hollywood career. The interview was recorded on videotape, and the recording displays some audio dropouts from time to time, but it’s certainly a fascinating and thorough look at Yates’ filmmaking career.

- Viewing Notes (2016) (19:00). Here, composer Stanley Silverman talks about his work on the film. It’s an excellent interview that begins with Silverman discussing his background and his musical influences before talking about his film scores. He discusses his work on Eyewitness, specifically, explaining the decisions he made in writing the score for the picture.

- The Janitor (103:03). This is a dub of the 1982 UK VHS release from Twentieth Century Fox, in its entirety, under the title ‘The Janitor’. It has been included so as to offer the viewer the option of watching an open-matte presentation of the film (which the UK VHS was) to compare with the main widescreen presentation. As it’s sourced from an aging VHS tape, viewers should adjust their expectations accordingly: it’s a lo-fi presentation, complete with tape damage (rolls and creases).

- Trailer (3:16).

- TV Spot (0:30).

Overall

Peter Yates’ Eyewitness is an interesting thriller that, in its focus on the cultural fallout of a war and its protagonist who may or may not be an unreliable witness to a crime, offers a riff on the themes of classic films noir that differs from the more erotic focus of many contemporaneous neo-noir pictures (for example, Body Heat). The picture has a strong cast and a tight script, and Yates handles the film well: it’s no The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Yates, 1973)… but then again, what is? Peter Yates’ Eyewitness is an interesting thriller that, in its focus on the cultural fallout of a war and its protagonist who may or may not be an unreliable witness to a crime, offers a riff on the themes of classic films noir that differs from the more erotic focus of many contemporaneous neo-noir pictures (for example, Body Heat). The picture has a strong cast and a tight script, and Yates handles the film well: it’s no The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Yates, 1973)… but then again, what is?

Signal One’s Blu-ray release of the picture is, like their other releases, exemplary. The main presentation is deeply impressive, and is supported by some absolutely superb contextual material – including a dub of the UK VHS release, under the title ‘The Janitor’, which offers the viewer the opportunity to watch an open-matte presentation of the picture. Whilst not necessarily ‘essential’, this is nonetheless a fascinating and very welcome inclusion, and the package as a whole represents a worthwhile purchase for fans of Yates, the actors or of the neo-noir mode in general.

|