|

|

Burnt Offerings (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th October 2016). |

|

The Film

Burnt Offerings (Dan Curtis, 1976) Burnt Offerings (Dan Curtis, 1976)

Ten years after Dan Curtis created the iconic American television show Dark Shadows (1966-71), a bizarre amalgam of soap opera and Gothic horror, and three years after he directed the important television movie The Night Stalker (1973) which kickstarted one of the most beloved of horror-themed television shows of the 1970s, Dan Curtis helmed this adaptation of Robert Marasco’s 1973 novel Burnt Offerings. Middle-class couple Ben and Marian Rolf (Oliver Reed and Karen Black) arrive, with their 12 year old son Davy (Lee Montgomery) and Ben’s ageing aunt Elizabeth (Bette Davis), at the large country home of the Allardyce family. They are greeted by Roz Allardyce (Eileen Heckart) and her wheelchair-bound brother Arnold (Burgess Meredith). Roz and Arnold offer the Rolfs the opportunity to rent the large, seemingly idyllic country retreat for a bargain price of $900 for the whole summer, on the proviso that the Rolfs care for the house and provide meals for Roz and Arnold’s reclusive elderly mother.  Ben has doubts, but Marian convinces him to accept the Allardyces’ offer. After the Allardyces have departed, Marian visits the sitting room of the elderly Mrs Allardyce and becomes enchanted by the many photographic portraits on a table there that stretch back to the mid-Nineteenth Century, and she becomes particularly fascinated by an antique music box. (‘Memories of a lifetime’, Marian says to herself.) Meanwhile, exploring the grounds Ben and Davy find an overgrown graveyard which seems to be the Allardyce family’s cemetery; but Ben notices that the most recent of the headstones dates from the 1890s and no-one has been buried there since then. Ben has doubts, but Marian convinces him to accept the Allardyces’ offer. After the Allardyces have departed, Marian visits the sitting room of the elderly Mrs Allardyce and becomes enchanted by the many photographic portraits on a table there that stretch back to the mid-Nineteenth Century, and she becomes particularly fascinated by an antique music box. (‘Memories of a lifetime’, Marian says to herself.) Meanwhile, exploring the grounds Ben and Davy find an overgrown graveyard which seems to be the Allardyce family’s cemetery; but Ben notices that the most recent of the headstones dates from the 1890s and no-one has been buried there since then.

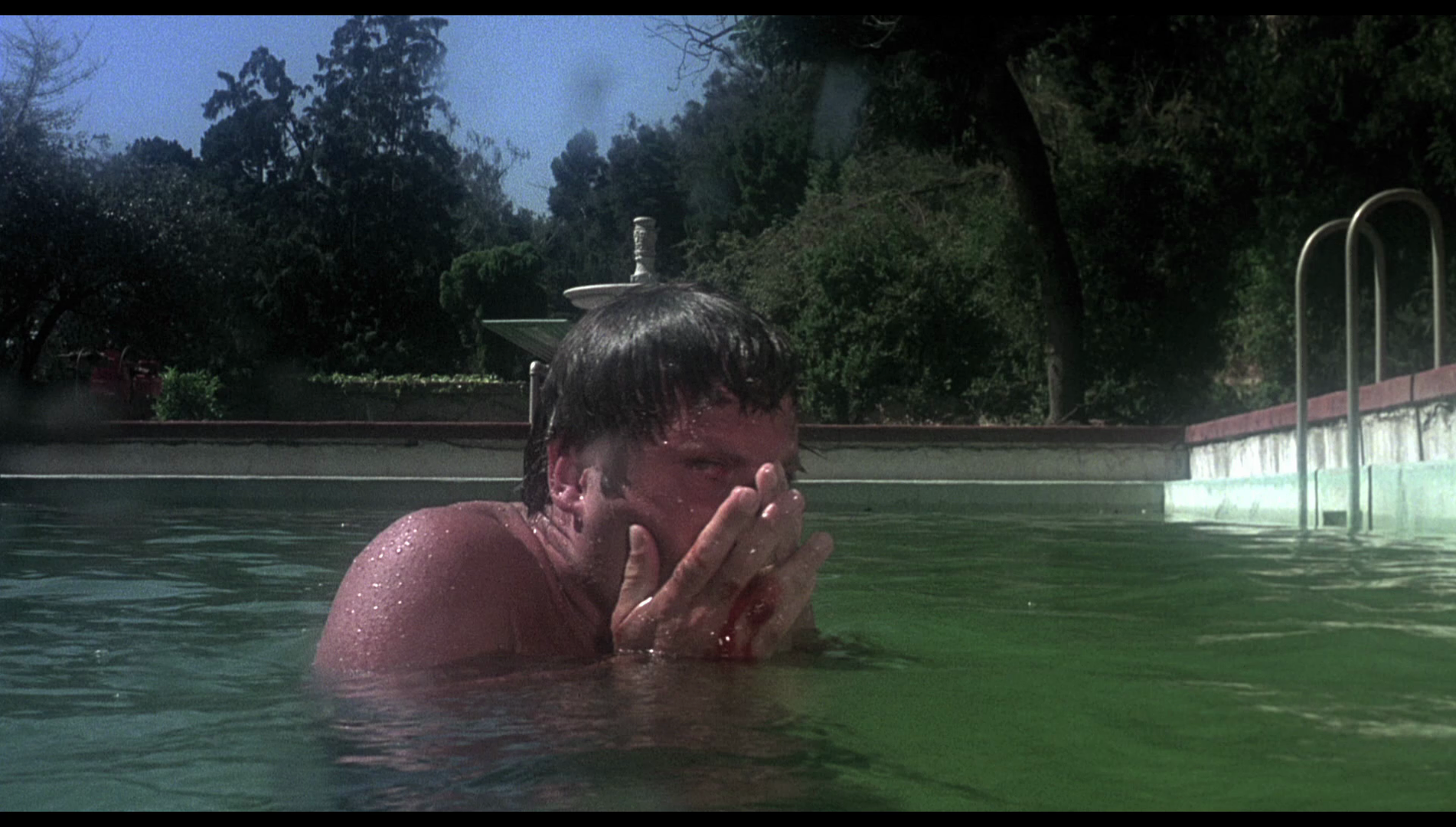

Ben repairs the dilapidated swimming pool. He and Davy swim in the pool, watched by Elizabeth. However, after discovering a pair of broken spectacles at the bottom of the pool, which he wears as a joke, Ben finds himself overcome by an unseen force and his play in the water becomes increasingly rough, frightening both Davy and Elizabeth. Ben also becomes haunted by nightmares of his mother’s funeral and especially the leering driver of the hearse carrying Ben’s mother. These dreams intrude on his daily existence, with Ben seeing the hearse driving along the road towards the house. Marian, on the other hand, displays an escalating fascination with Mrs Allardyce’s sitting room, rarely venturing away from it and even spending the night in the armchair there. She also begins to dress in an old-fashioned manner, and her hair starts to turn grey. Meanwhile, Aunt Elizabeth’s health begins to deteriorate, and as it does so the house seems to renew itself like a snake shedding its skin.  The implications of the title aren’t difficult to comprehend: the Rolfs are intended as a sacrifice, a ‘burnt offering’, to… something. The opening sequence contains some strong foreshadowing as to the supernatural events that take place later in the narrative. Apart from Ben’s hesitance towards the Allardyce’s offer, and the dead and decaying plants in the greenhouse attached to the building, as Ben approaches the front door he ominously (mis)quotes Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, declaring ‘Forward into the valley of death rode the 600’. The exact nature of what the Rolfs are sacrificed for, and the relationship between it and the Allardyce family, isn’t spelled out within the film or in the book on which it’s based. As a haunted house story, Marasco’s novel sits in a lineage that also includes Henry James novella The Turn of the Screw (1898), Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959), Richard Matheson’s Hell House (1971), Stephen King’s The Shining (1977) and Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black (1983). However, where those stories are about houses haunted by spirits or entities, Burnt Offerings is instead about a house that itself seems to be possessed and which seems to absorb the energies of those who dwell within it. Curtis’ film adaptation is strikingly faithful to the novel, but deletes some material from the start of the narrative depicting the Rolfs prior to their holiday, beginning instead with the Rolfs arriving at the house; and Curtis’ film also makes some changes to the film’s climax, altering the fates of two characters and building towards a denouement that alludes to Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) whilst also borrowing elements from Curtis’ earlier Night of Dark Shadows (1971). The implications of the title aren’t difficult to comprehend: the Rolfs are intended as a sacrifice, a ‘burnt offering’, to… something. The opening sequence contains some strong foreshadowing as to the supernatural events that take place later in the narrative. Apart from Ben’s hesitance towards the Allardyce’s offer, and the dead and decaying plants in the greenhouse attached to the building, as Ben approaches the front door he ominously (mis)quotes Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, declaring ‘Forward into the valley of death rode the 600’. The exact nature of what the Rolfs are sacrificed for, and the relationship between it and the Allardyce family, isn’t spelled out within the film or in the book on which it’s based. As a haunted house story, Marasco’s novel sits in a lineage that also includes Henry James novella The Turn of the Screw (1898), Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959), Richard Matheson’s Hell House (1971), Stephen King’s The Shining (1977) and Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black (1983). However, where those stories are about houses haunted by spirits or entities, Burnt Offerings is instead about a house that itself seems to be possessed and which seems to absorb the energies of those who dwell within it. Curtis’ film adaptation is strikingly faithful to the novel, but deletes some material from the start of the narrative depicting the Rolfs prior to their holiday, beginning instead with the Rolfs arriving at the house; and Curtis’ film also makes some changes to the film’s climax, altering the fates of two characters and building towards a denouement that alludes to Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) whilst also borrowing elements from Curtis’ earlier Night of Dark Shadows (1971).

In 1974, Curtis directed an adaptation of Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw; Burnt Offerings represents a stark alternative to the classic English ghost story (often seen as being embodied by the likes of The Turn of the Screw), sitting within the paradigms of American films about ghosts and hauntings that appeared after the mid-1960s. American horror films are fascinated with that old staple of the horror genre, the haunted house. However, in American horror films, especially those since the 1960s, and particularly since the popularity of The Exorcist (Wiliam Friedkin, 1973), stories about haunted houses take place in the present day and often overlap with the ‘demonic intercession’ theme in which one or more people becomes possessed by an entity residing in such a residence. The paradigm is mapped out in the lecture given by paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren in the recent film The Conjuring (James Wan, 2013): ‘Infestation, oppression and possession. Now infestation that's the whispering, the footsteps, the feeling of another presence, which ultimately grows into oppression, the second stage. Now this is where the victim, and it's usually the one who's the most psychologically vulnerable, is targeted specifically by an external force. Breaks the victim down, crushes their will. And once in a weakened state, leads into the third stage, possession’. This paradigm can be mapped in any number of haunted house films made in the 1970s and the beyond, from The Amityville Horror (Stuart Rosenberg, 1979),The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980) and The Evil Dead (Sam Raimi, 1981), through to more modern examples like Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007), Insidious (James Wan, 2010) and The Haunting in Connecticut (Peter Cornwell, 2009). Burnt Offerings contains some specific imagery that would find its way into the later The Evil Dead: notably, a sequence in which Ben takes Davy and tries to drive away from the house, only to find the road blocked by a felled tree. Ben gets out the car and attempts to move the tree, but he is attacked by a vine which winds its way round his legs – much like the attack upon Cheryl in Sam Raimi’s film. In 1974, Curtis directed an adaptation of Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw; Burnt Offerings represents a stark alternative to the classic English ghost story (often seen as being embodied by the likes of The Turn of the Screw), sitting within the paradigms of American films about ghosts and hauntings that appeared after the mid-1960s. American horror films are fascinated with that old staple of the horror genre, the haunted house. However, in American horror films, especially those since the 1960s, and particularly since the popularity of The Exorcist (Wiliam Friedkin, 1973), stories about haunted houses take place in the present day and often overlap with the ‘demonic intercession’ theme in which one or more people becomes possessed by an entity residing in such a residence. The paradigm is mapped out in the lecture given by paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren in the recent film The Conjuring (James Wan, 2013): ‘Infestation, oppression and possession. Now infestation that's the whispering, the footsteps, the feeling of another presence, which ultimately grows into oppression, the second stage. Now this is where the victim, and it's usually the one who's the most psychologically vulnerable, is targeted specifically by an external force. Breaks the victim down, crushes their will. And once in a weakened state, leads into the third stage, possession’. This paradigm can be mapped in any number of haunted house films made in the 1970s and the beyond, from The Amityville Horror (Stuart Rosenberg, 1979),The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980) and The Evil Dead (Sam Raimi, 1981), through to more modern examples like Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007), Insidious (James Wan, 2010) and The Haunting in Connecticut (Peter Cornwell, 2009). Burnt Offerings contains some specific imagery that would find its way into the later The Evil Dead: notably, a sequence in which Ben takes Davy and tries to drive away from the house, only to find the road blocked by a felled tree. Ben gets out the car and attempts to move the tree, but he is attacked by a vine which winds its way round his legs – much like the attack upon Cheryl in Sam Raimi’s film.

Post-1970 American haunted house films tend to follow a fairly similar set of narrative paradigms: a couple, usually middle-class, acquires a home that is supiciously beyond their means (and often, though not always, is in a secluded location, sometimes in the countryside). The fact that the house is beyond their means hints at a theme of aspiration and social mobility, and a desire to move up the proverbial ladder; but the supernatural events the inevitably follow suggest that this social mobility comes at a cost – often highly personal, involving the disruption to (and sometimes elimination of) an outwardly happy family unit. These narrative paradigms are still with us today, in films such as Insidious, Sinister (Scott Derrickson, 2012) and The Conjuring. They are also present in the currently popular American television shows about ghosts and hauntings, from those that are almost like modern oral folk tales and which involve re-enactments of eyewitness accounts (such as A Haunting, 2005-present; and Paranormal Witness, 2011-present), to the paranormal investigation programmes like Ghost Hunters (2004-present) and Ghost Adventures (2008-present). Post-1970 American haunted house films tend to follow a fairly similar set of narrative paradigms: a couple, usually middle-class, acquires a home that is supiciously beyond their means (and often, though not always, is in a secluded location, sometimes in the countryside). The fact that the house is beyond their means hints at a theme of aspiration and social mobility, and a desire to move up the proverbial ladder; but the supernatural events the inevitably follow suggest that this social mobility comes at a cost – often highly personal, involving the disruption to (and sometimes elimination of) an outwardly happy family unit. These narrative paradigms are still with us today, in films such as Insidious, Sinister (Scott Derrickson, 2012) and The Conjuring. They are also present in the currently popular American television shows about ghosts and hauntings, from those that are almost like modern oral folk tales and which involve re-enactments of eyewitness accounts (such as A Haunting, 2005-present; and Paranormal Witness, 2011-present), to the paranormal investigation programmes like Ghost Hunters (2004-present) and Ghost Adventures (2008-present).

The supernatural events are connected to the presence of the elderly Mrs Allardyce in the attic, but the exact nature of her relationship with what the Rolfs witness and experience isn’t made clear until the film’s climax. At the start of the film, Roz and Arnold tell the Rolfs that the rental for the house is ‘very reasonable […] for the right people’. Arnold watches Davy playing in the garden outside the house, commenting ‘He’s full of the devil too, isn’t he?’ Meanwhile, he and Roz talk about the house as if it were a person: ‘This house will be here long, long after you have departed’, Arnold tells the Rolfs. ‘It’s practically immortal’, Roz adds. The only catch in the rental, the Allardyces inform the Rolfs, is that the Rolfs must prepare food for the Allardyce’s hermit-like mother, who lives in a room on the top floor of the building: ‘You’ll probably never see her’, Arnold tells Ben and Marian. Ben has doubts about the place, believing – rightly – that there is a ‘catch’ and that the Allardyces are ‘two steps beyond crazy’. However, Marian’s sense of danger is overcome by her eye for a bargain: ‘Maybe they’re [the Allardyces are] not interested in money’, she says, ‘Maybe they just want somebody who’ll take care of the place’.  In 1982, reflecting on films such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), The Shining and Burnt Offerings, in which members of the middle classes come face to face with terror, Stephen Snyder commented that ‘the notion of [middle class] life as tantamount to the world of horror has been mushrooming’ (Snyder, quoted in Wheatley, 2012: np). By locating horror in the home, these films explored a ‘network of anxieties… often realised in terms of the troubling insatiateness which underlies the structure of American life’ (Snyder, quoted in ibid.). Marian’s fascination with the house is mitigated by Ben’s reminder that they don’t own it: it isn’t theirs. ‘Marian, this house is not yours’, Ben tells her after she has spent an inordinate amount of time caring for the property, ‘We do not own it, do you understand?’ ‘But it’s our responsibility’, she says. ‘What is more important to you?’, Ben asks, the house and all this… or us?’ As the narrative progresses, it becomes clear that the middle-class family can’t possess the house, but it can possess them. Later, after a series of inexplicable events have impacted negatively upon the family, Ben tells Marian that they are leaving. ‘How can we?’, she asks. ‘How? We just pack up and go, that’s how’, he tells her. ‘You’re obsessed with this. All of it’, Ben says, ‘Marian, this house is destroying’. ‘Darling, this house is everything, everything we have always wanted’, Marian says, foregrounding the bourgeois confusion of status and property ownership with aspirations and personal goals. (This was a key element of the novel which is rendered more subtly in this film adaptation, in terms of Marian’s fascination with the antique objects in the attic rooms.) The building, a (seemingly) inanimate object, is immutable – ‘immortal’, in the words of Roz. It cannot change. But human life is transient and impermanent: people live and die. The transience of human life is thus set against the immutability of the object, and the fact that the house manages to ‘possess’ its occupiers hints at a suggestion that the key determinant in people’s behaviour is their environment. This is something also suggested in The Amityville Horror and The Shining: in both films, a patriarch is ‘turned’ against their family when they move into a haunted building, the spirits possessing this figure of male authority who then seeks to commit familicide. In 1982, reflecting on films such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), The Shining and Burnt Offerings, in which members of the middle classes come face to face with terror, Stephen Snyder commented that ‘the notion of [middle class] life as tantamount to the world of horror has been mushrooming’ (Snyder, quoted in Wheatley, 2012: np). By locating horror in the home, these films explored a ‘network of anxieties… often realised in terms of the troubling insatiateness which underlies the structure of American life’ (Snyder, quoted in ibid.). Marian’s fascination with the house is mitigated by Ben’s reminder that they don’t own it: it isn’t theirs. ‘Marian, this house is not yours’, Ben tells her after she has spent an inordinate amount of time caring for the property, ‘We do not own it, do you understand?’ ‘But it’s our responsibility’, she says. ‘What is more important to you?’, Ben asks, the house and all this… or us?’ As the narrative progresses, it becomes clear that the middle-class family can’t possess the house, but it can possess them. Later, after a series of inexplicable events have impacted negatively upon the family, Ben tells Marian that they are leaving. ‘How can we?’, she asks. ‘How? We just pack up and go, that’s how’, he tells her. ‘You’re obsessed with this. All of it’, Ben says, ‘Marian, this house is destroying’. ‘Darling, this house is everything, everything we have always wanted’, Marian says, foregrounding the bourgeois confusion of status and property ownership with aspirations and personal goals. (This was a key element of the novel which is rendered more subtly in this film adaptation, in terms of Marian’s fascination with the antique objects in the attic rooms.) The building, a (seemingly) inanimate object, is immutable – ‘immortal’, in the words of Roz. It cannot change. But human life is transient and impermanent: people live and die. The transience of human life is thus set against the immutability of the object, and the fact that the house manages to ‘possess’ its occupiers hints at a suggestion that the key determinant in people’s behaviour is their environment. This is something also suggested in The Amityville Horror and The Shining: in both films, a patriarch is ‘turned’ against their family when they move into a haunted building, the spirits possessing this figure of male authority who then seeks to commit familicide.

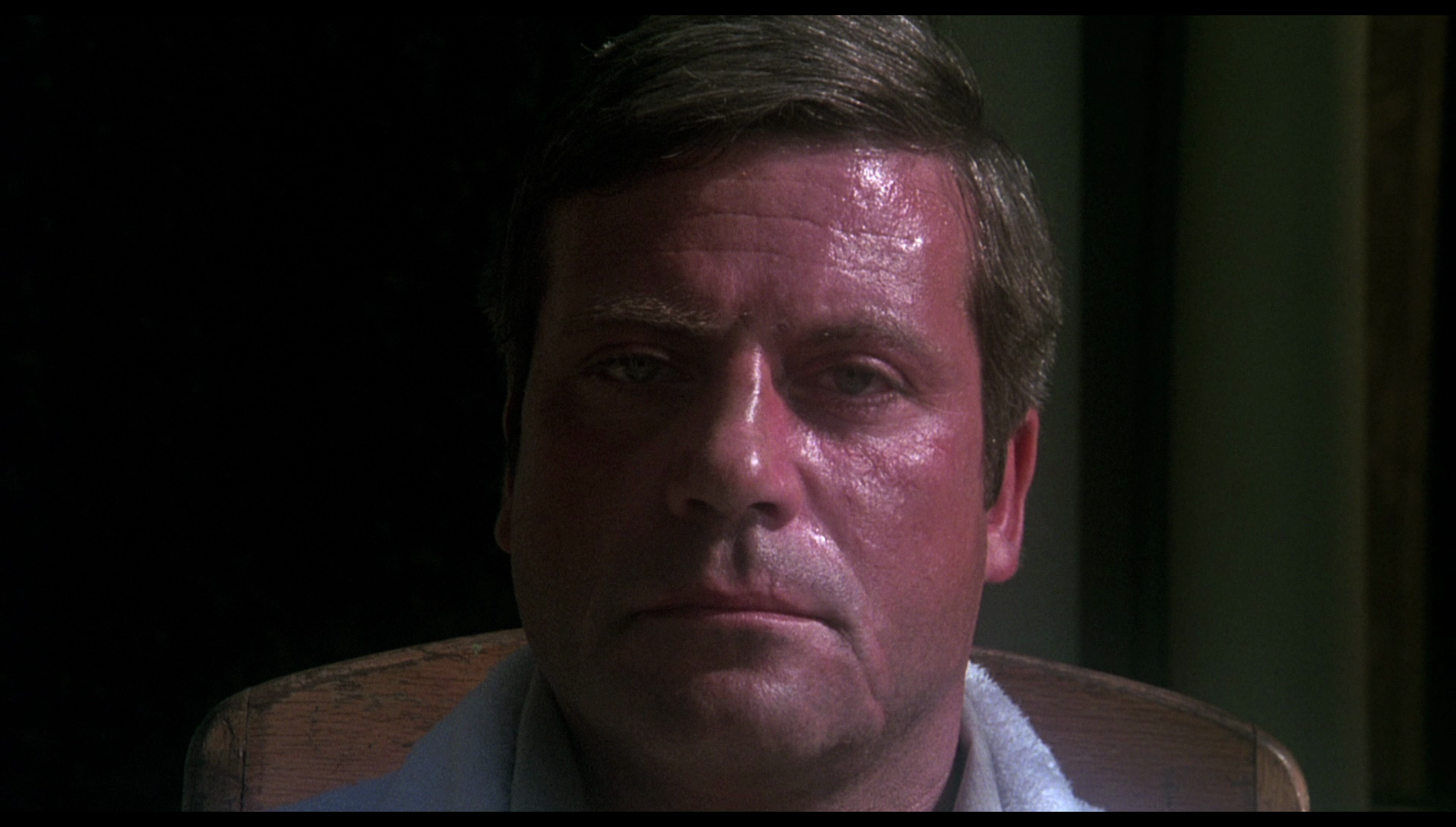

Colette Balmain has discussed the archetypes associated with these films, underscoring how at the heart of them is an anxiety about ‘the break-up of the nuclear family’ (Balmain, 2008: 128). Many of these films focus on ‘the sins of the father’ and corrupt patriarchs such as Jack Torrance in The Shining: as the narrative progresses and Torrance becomes increasingly possessed by the force that resides within the Overlook Hotel, his drinking increases and he becomes violent towards his family (ibid.). Likewise, in Burnt Offerings, after repairing the swimming pool and wearing the shattered spectacles that he finds on the bottom of it, Ben becomes inhabited by a force that causes him to assault Davy whilst playing with his son in the pool itself. Ben’s behaviour frightens Davy and Elizabeth, and terrifies Ben himself through the suggestion that he has the potential to harm his family and especially his son, whom Ben seems to love very much. The sequence plays on the seemingly universal fear of any parent, that one may lose control of oneself and harm one’s own child. ‘It’s all I can think of’, Ben tells Marian after the incident with Davy in the pool, ‘I can’t get it out of my head […] I wanted to hurt him [Davy], can you understand that? I wanted to hurt him’. Colette Balmain has discussed the archetypes associated with these films, underscoring how at the heart of them is an anxiety about ‘the break-up of the nuclear family’ (Balmain, 2008: 128). Many of these films focus on ‘the sins of the father’ and corrupt patriarchs such as Jack Torrance in The Shining: as the narrative progresses and Torrance becomes increasingly possessed by the force that resides within the Overlook Hotel, his drinking increases and he becomes violent towards his family (ibid.). Likewise, in Burnt Offerings, after repairing the swimming pool and wearing the shattered spectacles that he finds on the bottom of it, Ben becomes inhabited by a force that causes him to assault Davy whilst playing with his son in the pool itself. Ben’s behaviour frightens Davy and Elizabeth, and terrifies Ben himself through the suggestion that he has the potential to harm his family and especially his son, whom Ben seems to love very much. The sequence plays on the seemingly universal fear of any parent, that one may lose control of oneself and harm one’s own child. ‘It’s all I can think of’, Ben tells Marian after the incident with Davy in the pool, ‘I can’t get it out of my head […] I wanted to hurt him [Davy], can you understand that? I wanted to hurt him’.

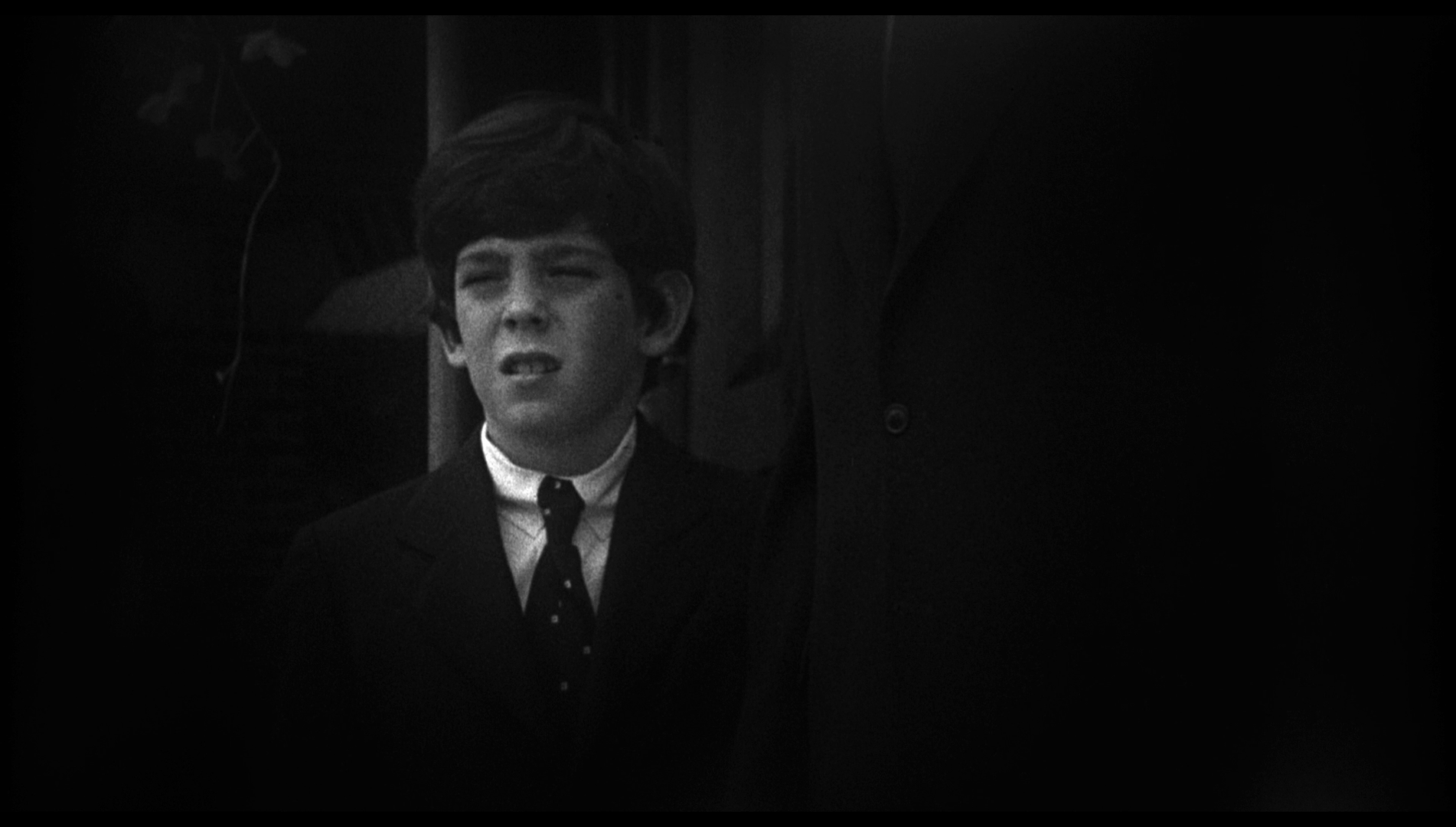

However, at this point in the film Ben has already been depicted as childlike, playing with his son as if he were an equal, and haunted by a trauma in his past that isn’t described but only hinted at through a series of analepses that take place in the film. These analepses, which first present themselves as nightmares (shot in stark monochrome) whilst the Rolfs are staying in the Allardyce house, take Ben back to the funeral of his mother – at which he was terrified by the leering driver (Anthony James) of his mother’s hearse. As these visions increase and intrude upon his daytime reality (he sees the hearse and the driver whilst trimming the bushes in the grounds of the house), they leave Ben paralysed with terror, sweating and unable to speak or move. In the sheer panic which overcomes Ben when he recalls this event and the leering look on the driver’s face, there’s a subtle suggestion that this terror is sexual, that the young Ben was molested by the driver of the hearse. This suggestion of sexual trauma is reiterated partway through the film when, after Marian has already fallen deeply under the spell of the house, Ben suggests the couple take part in a spot of nighttime skinny dipping. Ben attempts to seduce Marian on the lawn in front of the house, but she looks up at the window of Mrs Allardyce’s room and resists; however, Ben continues to claw at her, and the viewer would be forgiven for thinking that this scene will climax with Ben raping his wife. However, Ben stops and Marian flees to the sanctity of the house.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Taking up just under 30Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc, Burnt Offerings is presented here uncut, with a running time of 116:00 mins. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Taking up just under 30Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc, Burnt Offerings is presented here uncut, with a running time of 116:00 mins.

From the outset, colour reproduction is good, with the lush green of the foliage around the house being represented nicely and skintones seeming accurate. There’s a good level of detail, certainly a noticeable improvement over the old MGM DVD release. Contrast levels are very good, with strong midtones and defined shadows. This is particularly noticeable in Ben’s monochrome nightmare sequence, the black and white photography having very good contrast. The dark interiors are filled with shadow and menace, and this is represented well here. Some scenes, both exteriors (eg, the footage around the swimming pool) and interiors, were shot with noticeably diffused light – so if you haven’t seen the film before, be prepared for this: it’s a characteristic of the film’s original photography that seems more obvious with this HD presentation, thanks to the boost in detail and the improvement in contrast, than in the film’s previous DVD releases. Many of the interiors were shot with wide-angle lenses which introduced an element of barrel distortion – again, a product of the original photography. There’s some very minor damage present here and there throughout this presentation; this extends to minor flecks and specks and one (or possibly two) fleeting burn marks, but certainly nothing that should detract from one’s enjoyment of the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 track. This is clear and represents the film’s rich score effectively, the soundscape dominated by cellos and shrill violins. The audio track is a huge improvement over the audio on MGM’s DVD release of the film, which as I recall was quite muted and ‘muddy’. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes:  - An audio commentary with Dan Curtis, Karen Black and William F Nolan. Recorded for the film’s DVD release in the early/mid-2000s, this is a lively commentary featuring the film’s director, one of its stars and the screenwriters. Curtis begins by talking about the first fifteen minutes of the early cut of the film, which corresponded to the opening chapters of Marasco’s source novel which depicted the Rolfs’ daily lives prior to their arrival at the Allardyce house. They discuss the locations used in the film and some of the casting decisions. - An audio commentary with Dan Curtis, Karen Black and William F Nolan. Recorded for the film’s DVD release in the early/mid-2000s, this is a lively commentary featuring the film’s director, one of its stars and the screenwriters. Curtis begins by talking about the first fifteen minutes of the early cut of the film, which corresponded to the opening chapters of Marasco’s source novel which depicted the Rolfs’ daily lives prior to their arrival at the Allardyce house. They discuss the locations used in the film and some of the casting decisions.

- A second audio commentary with critic Richard Harland Smith. In another impressive commentary track, Richard Harland Smith discusses the film. He talks about the connotations of the title and the relationship between Marasco’s novel and this film adaptation. He talks about the film’s relationship with Gothic horror fiction. There’s much detailed discussion of the film’s themes too, suggesting that ‘horror films help you understand how good people go bad’. He suggests that the novel was ‘a take on the American dream, on mistaking acquisition for achievement, on being content with having “stuff”’. - ‘Anthony James: Acting His Face’ (17:31). Taking its title from James’ autobiography, this featurette sees the actor reflecting on his career. He talks about his role in In the Heat of the Night (Norman Jewison, 1967) before reflecting on his performance in Burnt Offerings, talking about the discussions he had with Bette Davis on the film’s set. He praises Oliver Reed’s work. James also discusses his work as an artist, and comments on Clint Eastwood’s work as an ‘actor’s actor and director’, focusing on Unforgiven (Eastwood, 1992), in which James had a role.  - ‘Blood Ties’ (16:28). Here, Lee Montgomery talks about his experiences working on the film. He spends some time talking about Curtis’ Dark Shadows before reflecting on the shooting of Burnt Offerings. He says that Oliver Reed ‘wanted to get smacked around. The more he could bleed in the scene, it was awesome’. He discusses Reed’s reputation as a brawler and Reed’s entourage, who called themselves ‘Reed’s Raiders’. He talks about the shooting of the scene in which the vine wraps itself around Ben’s leg and reveals that it was shot in reverse, just like the vine attack in The Evil Dead. - ‘Blood Ties’ (16:28). Here, Lee Montgomery talks about his experiences working on the film. He spends some time talking about Curtis’ Dark Shadows before reflecting on the shooting of Burnt Offerings. He says that Oliver Reed ‘wanted to get smacked around. The more he could bleed in the scene, it was awesome’. He discusses Reed’s reputation as a brawler and Reed’s entourage, who called themselves ‘Reed’s Raiders’. He talks about the shooting of the scene in which the vine wraps itself around Ben’s leg and reveals that it was shot in reverse, just like the vine attack in The Evil Dead.

- ‘From the Ashes’ (13:20). In this interview with the film’s screenwriter William F Nolan, Nolan reflects on his association with Curtis which began with the television movie The Norliss Tapes in 1973. Nolan discusses the house that Curtis lived in, and which Curtis claimed to be haunted – and which Curtis sold because he was afraid of the experiences escalating. Nolan reflects on the themes of Burnt Offerings and talks about the production itself. - ‘Portraits of Fear’ (3:20). This is an animated gallery of production stills and promotional materials, including the covers for Marasco’s source novel. - Trailer (2:28).

Overall

Burnt Offerings is an excellent ghost film, deeply memorably thanks in large part to some impressive performances from its cast. The narrative itself fits the archetypes of the American ghost story that are still prevalent today, in films such as The Haunting in Connecticut or The Conjuring. The climax is perhaps a little clumsy and forced, but the film as a whole is thought-provoking and undeniably creepy. Burnt Offerings is an excellent ghost film, deeply memorably thanks in large part to some impressive performances from its cast. The narrative itself fits the archetypes of the American ghost story that are still prevalent today, in films such as The Haunting in Connecticut or The Conjuring. The climax is perhaps a little clumsy and forced, but the film as a whole is thought-provoking and undeniably creepy.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of the film contains a very pleasing presentation of the film which is a vast improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases, especially in terms of its audio track. The Blu-ray itself contains some very good contextual material. The interviews with the participants are all very good, especially the interview with William F Nolan. The new commentary with Richard Harland Smith is also very impressive and contains some fascinating discussion of the film’s themes. Horror fans will find this release to be a very pleasing purchase. References: Balmain, Colette, 2008: Introduction to the Japanese Horror Film. Edinburgh University Press Whatley, Catherine, 2012: ‘Michael Haneke and the Horrors of Everyday Existence’. In: Allmer, Patricia et al (eds), 2012: European Nightmares: Horror Cinema in Europe Since 1945. London: Wallflower Press

|

|||||

|