|

|

Story of Sin (The) AKA Dzieje Grzechu (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th March 2017). |

|

The Film

The Story of Sin (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975) The Story of Sin (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975)

Please also see our reviews of Arrow’s Blu-ray releases of other Borowczyk films: Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal (1967), Goto, l'île d'amour (1968), Blanche (1972), Contes Immoraux (1974), La Bęte (1975) and Le cas étrange de Dr Jekyll et Miss Osbourne (1981). In a confession booth, Ewa Pobratynska (Grazyna Dlugolecka), a young and innocent middle-class girl, is warned by a priest not to give in to lust. She returns to the home of her family; Ewa’s father (Zdzislaw Morozewski) has been struck by unemployment and has taken to renting out rooms to lodgers, including self-labelled ‘philosopher’ Adolf Horst (Marek Bargielowski). Horst’s sole source of entertainment seems to come from ‘entertaining’ prostitutes. When anthropology student Lukasz Niepolomski (Jerzy Zelnik) arrives at the Pobratynska residence looking for rooms to rent, Ewa is smitten. However, Lukasz is married – though he is attempting to divorce his wife. Lukasz manages to secure Ewa’s father a job at a factory owned by a friend of Lukasz. Ewa and Lukasz exchange love notes. When Lukasz reveals that his plea for a divorce has been rejected, he reveals that he plans to leave Warsaw and refuses to pass his new address on to Ewa. Ewa is heartbroken. After seeing a piece by Lukasz published in a newspaper, Ewa approaches the editor and, under pretence of being a fellow student, manages to secure Lukasz’ address. She travels by train and joins Lukasz, who vows that he will borrow money from his employer, Count Zygmunt Szczerbic (Olgierd Lukaszewicz), and travel to Rome; there, he says, he is sure to get the divorce he so desires.  Ewa travels by train and is approached by two ruffians who promise her a sum of money, ‘enough to have fun for a week’. She refuses, and the men mock her piousness: ‘Airs and graces, eh? You’ll beg me yet’, one of the men says. She discovers that Lukasz is in hospital, having been shot by Count Szczerbic in a duel apparently over Ewa’s honour. Ewa takes a job as a seamstress, and when Lukasz recovers he and Ewa stay in the same lodgings but in separate rooms. However, one day Ewa gives in to Lukasz and the pair have sex. Ewa travels by train and is approached by two ruffians who promise her a sum of money, ‘enough to have fun for a week’. She refuses, and the men mock her piousness: ‘Airs and graces, eh? You’ll beg me yet’, one of the men says. She discovers that Lukasz is in hospital, having been shot by Count Szczerbic in a duel apparently over Ewa’s honour. Ewa takes a job as a seamstress, and when Lukasz recovers he and Ewa stay in the same lodgings but in separate rooms. However, one day Ewa gives in to Lukasz and the pair have sex.

Lukasz leaves for Rome. However, Count Szczerbic brings news to Ewa that Lukasz has been arrested for selling documents alleged to be stolen from the Hungarian Embassy. In Lukasz’ absence, Ewa discovers she is pregnant. She gives birth in secret and abandons the baby to certain death. After returning home, where she is admonished by her mother but embraced by her father, Ewa takes a job processing payments at a café. She is approached by Count Szczerbic. He vows to take Ewa to Rome, to visit Lukasz. They arrive in Rome, but Lukasz seems to have been released. Szczerbic takes Ewa to Monte Carlo and its casinos, in search of Lukasz. There, a young man tells Ewa that Lukasz has ‘married’ another woman. In frustration, Lukasz allows herself to be seduced by this young man. She travels to Schuttenbach and takes a room there. A man enters and rapes Ewa at knifepoint. It is Horst; he demands that she treat him as ‘your master; your husband, if anyone asks’. Horst introduces Ewa to the sinister Count Plaza-Splawski (Marek Walczewski). Horst and the bankrupt Count Plaza-Splawski have hatched a plan to use Ewa to steal the wealth of Count Szczerbic.  Stefan Zeromski’s source novel had already been adapted for the screen twice, by Antoni Bednarczyk in 1911 (as Dzieje grzechu, the novel’s Polish title) and in 1933 by Henryk Szaro (under the same title, and released in English as Story of a Sin). The film marked Borowczyk’s return to Poland following a series of pictures made in France. With The Story of Sin, Borowczyk delivered a fairly restrained historical melodrama which was received positively by most critics, and the film went some way towards redeeming Borowczyk in the eyes of those critics who felt that his previous picture, Contes immoraux (Immoral Tales, 1973), was… well, immoral. However, with his subsequent picture, La bęte (The Beast, 1975), Borowczyk would retreat into controversy. Stefan Zeromski’s source novel had already been adapted for the screen twice, by Antoni Bednarczyk in 1911 (as Dzieje grzechu, the novel’s Polish title) and in 1933 by Henryk Szaro (under the same title, and released in English as Story of a Sin). The film marked Borowczyk’s return to Poland following a series of pictures made in France. With The Story of Sin, Borowczyk delivered a fairly restrained historical melodrama which was received positively by most critics, and the film went some way towards redeeming Borowczyk in the eyes of those critics who felt that his previous picture, Contes immoraux (Immoral Tales, 1973), was… well, immoral. However, with his subsequent picture, La bęte (The Beast, 1975), Borowczyk would retreat into controversy.

The Story of Sin was made remarkably quickly, Borowczyk shooting in seventy locations in just sixty days (Mikurda, 2015: 29). By all reports, the relationship on set between Borowczyk and his lead actress was deeply tense, Dlugolecka later complaining that the film ended her acting career owing to the association it created in the minds of audiences and members of the Polish film industry of her with nudity and scenes of sexuality (Dlugolecka, cited in ibid.: 29-30). Paul Coates notes that The Story of Sin was made at a time when, in Poland, the ‘state’s attitude to filmic depictions of religion […] swayed uneasily between ambivalence, self-contradiction, self-deluded wishful thinking, opportunism and anti-clerical militancy’ (Coates, 2005: 87). The suppression of Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Decameron (1970) in Poland was, Coates argues, ‘a tactic’ intended to highlight within Poland’s Catholic community the types of ‘shocking and anti-clerical films’ being ‘made and distributed in the West’ (ibid.).  The fact that such films were withheld from public consumption, Coates contends, spoke more of ‘State opposition to pornography […] than to concern for the tender consciences of Catholic viewers’, some of which was down to a ‘dislike of the pornographic elevation of couples and their private, backroom interchanges above collective activity within the controlled public space of factory or street’ (ibid.). However, ‘the depth of the contradictoriness that finally doomed Party policy to collapse’ is evidenced via ‘the simultaneous promotion of genuine pornography whenever it could be deemed an irritant to the church’ (ibid.). Coates points to The Story of Sin as a particular example of this: the film was initially subjected to some criticism from within the Party but Borowczyk ‘gained approval by going before the minister (of Culture) and stating “I’ve just come out of a meeting with the bishop, and the Church opposes the making of this film”’ (Borowczyk, quoted in ibid.: 88). As Kuba Mikurda states, The Story of Sin was made ‘[j]ust to spite the ideologically adverse church’ (Mikurda, 2015: 28). The fact that such films were withheld from public consumption, Coates contends, spoke more of ‘State opposition to pornography […] than to concern for the tender consciences of Catholic viewers’, some of which was down to a ‘dislike of the pornographic elevation of couples and their private, backroom interchanges above collective activity within the controlled public space of factory or street’ (ibid.). However, ‘the depth of the contradictoriness that finally doomed Party policy to collapse’ is evidenced via ‘the simultaneous promotion of genuine pornography whenever it could be deemed an irritant to the church’ (ibid.). Coates points to The Story of Sin as a particular example of this: the film was initially subjected to some criticism from within the Party but Borowczyk ‘gained approval by going before the minister (of Culture) and stating “I’ve just come out of a meeting with the bishop, and the Church opposes the making of this film”’ (Borowczyk, quoted in ibid.: 88). As Kuba Mikurda states, The Story of Sin was made ‘[j]ust to spite the ideologically adverse church’ (Mikurda, 2015: 28).

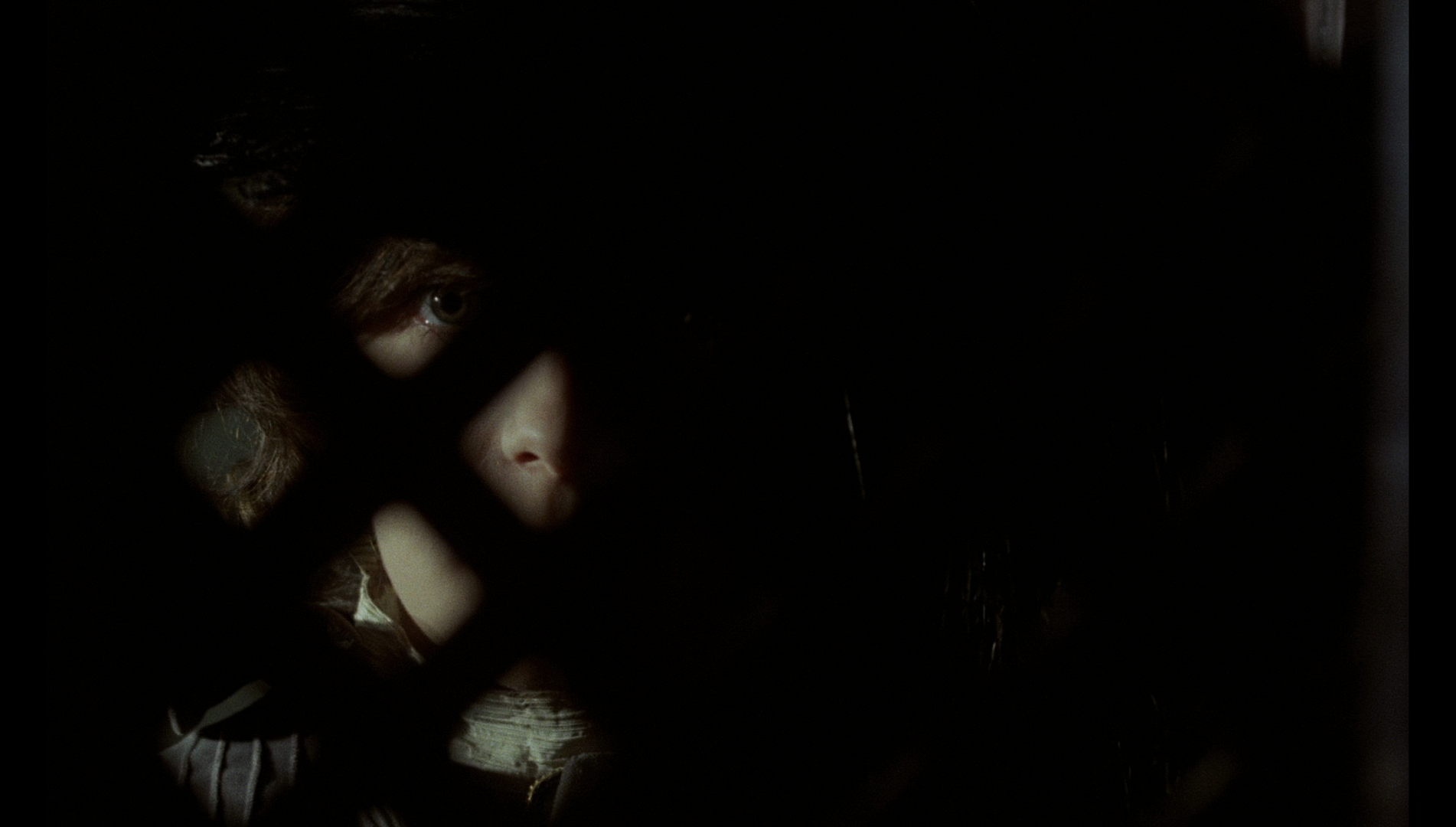

Borowczyk’s picture establishes its thematic territory very quickly, opening with an almost didactic dialogue between Ewa and a priest, Jutkiewicz (Zbigniew Zapasiewicz), that focuses on the nature of sin and sets the context for the narrative that follows. The dialogue takes place in a confession booth. As the film opens, we hear a church bell and are presented with a series of close-ups – the eye and cupped hand of the priest. ‘I do not recall having committed any venial sins’, Ewa says, offscreen. ‘St Ciprian calls virgins “fragrant flowers of the Church, embellishments of human nature. The perfect work of that nature immune to corruption. Representation of the Creator’s holiness”’, Jutkiewicz asserts before reminding Ewa that ‘to achieve a beautiful sin is within thy power. Try to make thy soul as beautiful as your flesh. Close your eyes to the sight of sin’. Jutkiewicz’s words echo, as if they are addressed to the audience rather than to Ewa – a warning of the ‘sins’ that the film’s viewers will see unfold on the cinema screen. Ewa asks what sin is and how she may recognise it. Jutkiewicz tells her that sin ‘is an evil deed’ and ‘must be a deliberate deed. He who does wrong, raises his hand against God. Sin is an offence against God. Its inner cause is imagination and lust. Its outer cause is another man, or Satan. Satan clouds man’s mind, quickens his imagination and incites lust. Never read books which spread sin. Look not at obscene paintings. Avoid things which may be charming outside but filthy inside’. Again, Jutkiewicz’s warning seems ironic given the context in which it appears and the expectations the audience may have for the film itself, based on Borowczyk’s most recent picture (Contes immoraux) and, especially, his subsequent film (La bęte, expanded from a segment originally shot for inclusion in Contes immoraux) and the controversy that surrounded their handling of themes of sexuality.  The opening sequence juxtaposes the spiritual (the church and the priest’s words of warning to Ewa) with the corporeal (Ewa’s return home, to find Horst cavorting with a prostitute and her father drunk). Jutkiewicz is contrasted with Ewa’s father, who in response to Ewa’s question ‘Why not go to confession?’, responds with anger (‘Don’t start telling me how to live my own life!’). The film narrativises Ewa’s transition from one state to the other, her experiences, instigated by her lust for Lukasz, leading her along a path of debauchery – culminating in a ‘fall’ from her status as a young lady of the petit bourgeois, ending her life as a prostitute, bitter and resentful, and motivated by money. The story is a familiar one, reminiscent of John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748) or the Marquis de Sade’s Justine (1791): an innocent young woman is introduced to the ‘pleasures of the flesh’, only for this to a spiralling series of incidents which move her away from the spiritual and towards the corporeal. Daniel Bird has suggested similarities between Borowczyk’s adaptation of The Story of Sin and Roman Polanski’s later adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (in 1983), in that both stories are set within a similar era and focus on Christian society’s refusal ‘to distinguish between the victim and the victimiser’ (Bird, 2002: 70). The opening sequence juxtaposes the spiritual (the church and the priest’s words of warning to Ewa) with the corporeal (Ewa’s return home, to find Horst cavorting with a prostitute and her father drunk). Jutkiewicz is contrasted with Ewa’s father, who in response to Ewa’s question ‘Why not go to confession?’, responds with anger (‘Don’t start telling me how to live my own life!’). The film narrativises Ewa’s transition from one state to the other, her experiences, instigated by her lust for Lukasz, leading her along a path of debauchery – culminating in a ‘fall’ from her status as a young lady of the petit bourgeois, ending her life as a prostitute, bitter and resentful, and motivated by money. The story is a familiar one, reminiscent of John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748) or the Marquis de Sade’s Justine (1791): an innocent young woman is introduced to the ‘pleasures of the flesh’, only for this to a spiralling series of incidents which move her away from the spiritual and towards the corporeal. Daniel Bird has suggested similarities between Borowczyk’s adaptation of The Story of Sin and Roman Polanski’s later adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (in 1983), in that both stories are set within a similar era and focus on Christian society’s refusal ‘to distinguish between the victim and the victimiser’ (Bird, 2002: 70).

Ewa’s relationship with Lukasz begins when he takes lodgings in her family’s house. Lukasz is a student of anthropology who is in the process of trying to secure a divorce from his wife. ‘Divorce?’, Ewa’s father questions when he hears of this, ‘No easy thing, particularly with the Catholic Church’. ‘That’s a hard nut to crack’, Lukasz responds. When Ewa and Lukasz flirt and frolic in a park on a bright summer’s day, Ewa on her way to church, Ewa tells Lukasz her name for the first time. Her name is that of ‘[t]he first sinner’, she reminds him. ‘Ewa in the Hebrew means “to exist”’, Lukasz tells her, ‘a charming verb in the infinitive’. We next see Ewa in church, turning away from Jutkiewicz before taking the Communion in acknowledgement of her desire for Lukasz, and experiencing fragmentary visions of a man firing a pistol (which turn out to be examples of prolepsis). When Lukasz’ divorce is refused and Lucaz leaves Warsaw, he refuses to tell Ewa exactly where he is going – to prevent her from following him. An embittered Ewa promises her parents that if they let Lukasz’ room to another lodger, ‘I’ll walk the streets and go with the first man who comes along’.  As soon as she leaves home to enter the world of Lukasz, Ewa’s background as a member of the bourgeoisie is mocked. First, she is mocked cruelly by two men who, in a train carriage, attempt to buy sexual favours from her; and when Ewa responds in the negative, one of the men sneers at her ‘Airs and graces’, promising to Ewa ‘You’ll beg me yet’. Then, following the shooting of Lukasz in a duel with Count Szczerbic, Ewa takes a job as a seamstress; there, she is ridiculed by her colleagues. ‘A Warsaw lady’, Ewa’s colleagues say mockingly. As soon as she leaves home to enter the world of Lukasz, Ewa’s background as a member of the bourgeoisie is mocked. First, she is mocked cruelly by two men who, in a train carriage, attempt to buy sexual favours from her; and when Ewa responds in the negative, one of the men sneers at her ‘Airs and graces’, promising to Ewa ‘You’ll beg me yet’. Then, following the shooting of Lukasz in a duel with Count Szczerbic, Ewa takes a job as a seamstress; there, she is ridiculed by her colleagues. ‘A Warsaw lady’, Ewa’s colleagues say mockingly.

Ewa is enticed into the world of sexuality by Lukasz’ good looks and his charm. ‘Shame’s an invention, like clothes’, Lukasz tells Ewa, ‘I wanted to teach you some anthropology. Woman’s shame is the invention of man’. With this, Ewa and Lukasz give in to their desire for one another and fuck for the first time. This spurs Lukasz on to travel to Rome, in an attempt to have his divorce validated. The product of this union is the baby Ewa gives birth to whilst Lukasz is being held by the police in Rome; committing her first act of murder, Ewa abandons the child, leaving it to certain death. From this point, Ewa’s engagement with ‘sin’ escalates. When Ewa is told that Lukasz has abandoned her and ‘married’ another woman, she has intercourse with the young man who gives her this news, the act representing an escalation of Ewa’s transition along the path that, in the film’s opening sequence, Jutkiewicz warned her against. However, shortly after doing this Ewa discovers that this news was false: Lukasz had become involved in an altercation with Horst, again over Ewa’s reputation. ‘Now I know he [Lukasz] is an honest man’, Ewa sighs desperately. Ewa’s ‘conversion’ is represented by the fact that following this incident, she begins to wear black rather than the white clothing which which she was associated earlier in the film.  In Schuttenbach, the lewd, sleazy Horst claims to recognise Ewa as similar in spirit to himself: ‘The likes of us need no babies’, he says, ‘We’re means to wander, to roam the world’. He rapes Ewa, forcing her into submission; and working with Plaza-Splawski, Horst pressures Ewa into helping them to rob Szczerbic. He mocks Ewa’s connection to the letter she has received from her true love, Lukasz (‘Reading the cry baby stuff again, hmmm? Leave it for a graphologist’, Horst says). Then Horst and Plaza-Splawski give Ewa a hypodermic syringe which they claim contains an anaesthetic, but only after Ewa has plunged the syringe’s contents into Szczerbic (after she has engaged in coitus with him) do they reveal that it actually contains curare. They force Ewa to watch as the paralysed Szczerbic loses consciousness and dies. In Schuttenbach, the lewd, sleazy Horst claims to recognise Ewa as similar in spirit to himself: ‘The likes of us need no babies’, he says, ‘We’re means to wander, to roam the world’. He rapes Ewa, forcing her into submission; and working with Plaza-Splawski, Horst pressures Ewa into helping them to rob Szczerbic. He mocks Ewa’s connection to the letter she has received from her true love, Lukasz (‘Reading the cry baby stuff again, hmmm? Leave it for a graphologist’, Horst says). Then Horst and Plaza-Splawski give Ewa a hypodermic syringe which they claim contains an anaesthetic, but only after Ewa has plunged the syringe’s contents into Szczerbic (after she has engaged in coitus with him) do they reveal that it actually contains curare. They force Ewa to watch as the paralysed Szczerbic loses consciousness and dies.

After an indefinite period of time has passed, Ewa is shown working as a streetwalker who plies her services under an assumed name (‘Anna Winter’). She is approached by a man, Count Cyprian Bozanta (Mieczyslaw Voit), and takes him back to her flat. Bozanta asks Ewa her name. She responds angrily, asking him ‘What do you want my real name for?’ ‘I’d like to talk to you as a human being, not as a streetwalker’, Bozanta tells her. In response to this, Ewa angrily spits the word ‘Benefactor!’ at Bozanta. ‘Sex or talk, you shouldn’t care’, Bozanta says, foregrounding the fact that he’s willing to pay for his time with Ewa. ‘It’s not the same’, she tells him, ‘No sex, no deal’. Bozanta offers Ewa a clerical job on his estate, which turns out to be a retreat for ‘reformed women’ where women deliver didactic dialogue about their repression and exploitation within ‘straight’ society. ‘Who misses men’s tyranny?’, one of the women asks; ‘We’re happier without men’, another woman responds. For once, Ewa seems to find contentment and confesses to Bozanta her most painful crime (‘I killed my baby’, she tells him once he has earnt her trust), but this is snatched away from her when Horst and Plaza-Splawski appear on the estate and accuses Bozanta of finding pleasure in ‘picking up human refuse’. However, before this happens Bozanta delivers what is perhaps the film’s most telling line of dialogue: ‘The pain of possession leads to the grace of loss’, he suggests, ‘The grace of loss leads to the pain of possession. I am bored with my virtues’.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The Story of Sin is uncut and runs for 130:44 mins. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The Story of Sin is uncut and runs for 130:44 mins.

The film was shot on 35mm negative film, and this presentation is a 2k restoration based on the original negative. Borowczyk’s preference for the 50mm focal length has been expressed a number of times (for example, by Noël Véry in the special features of Arrow’s previous Blu-ray releases of Borowczyk films), and this picture is no exception. The 50mm focal length allows Borowczyk’s camera to pick out elements within the mise-en-scčne without the barrel distortion associated with wide-angle lenses or the sometimes distracting flattening of perspective that one sees with telephoto lenses. The texture of the film is striking – like that of many of Borowczyk’s other films, including The Beast and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Miss Osbourne. The mise-en-scčne is filled with period detail and antiques (various nicknacks – portraits, objects, objets d’art), the frame dominated by earthy browns and greens. The use of the 50mm focal length to pick out details makes many of the interior sequences feel very claustrophobic – something which reinforces the film’s themes of repression and exploitation in a highly effective manner. The presentation carries a superb level of detail, with fine detail evident in the close-ups of characters and objects. Contrast levels are very pleasing, with deep shadows and defined midtones balanced by soft highlights. Many sequences show evidence of diffused light, something which previous home video transfers have struggled to communicate effectively but which is handled very well in this HD presentation of the film. There is no distracting damage to the source present throughout the presentation, and no evidence of harmful digital tinkering. Finally, the encode to disc is very strong, ensuring the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, in Polish and with optional English subtitles. The audio track is clear and free from problems, evidencing a strong sense of range. The subtitles, based on a new translation of the Polish dialogue, are free from errors and easy to read. It’s a rich, deep and rounded track.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by Samm Deighan and Kat Ellinger. Ellinger and Deighan, the editor-in-chief and associate editor of Diabolique Magazine respectively, have a slightly wobbly and hesitant start but soon find their groove. - An introduction by Andrzej Klimowski (8:22), the film’s poster designer. Klimowski talks about his first encounter with Borowczyk via Borowczyk’s short films. He reflects on Borowczyk’s animated films and praises the element of ‘physicality in art’ – suggesting that digital techniques can’t capture the subtleties and nuances of Borowczyk’s animated pictures. The interview is in English. - ‘The First Sinner’ (23:33). This is a new interview, in Polish with optional English subtitles, with the film’s lead actress, Grazyna Dlogolecka. Dlogolecka reflects on her disagreements with Borowczyk during the shooting of the picture. She comments on her first meeting with Borowczyk and how she came to be cast as Ewa, and she reflects on Borowczyk’s approach to directing actors – which she suggests was ‘only kind of moving on with the text [….] The important thing was to fit in with the setting and the artistic picture painted by him [Borowczyk]’. - ‘The Music Box’ (19:00). David Thompson reflects on the use of classical music in Borowczyk’s cinema. Thompson reflects on the music in Borowczyk’s early short films, through to his feature films. - ‘Stories of Sin’ (11:49). This new video essay by Daniel Bird focuses on the relationships between The Story of Sin and Borowczyk’s other films, highlighting some of the visual and narrative paradigms in the director’s films. The video essay comprises footage from a number of Borowczyk’s films, used to illustrate the qualities that define the director’s cinema. - Trailer (2:10). - Short Films: o ‘Once Upon a Time’ (9:11). This example of ‘cut-out animation’, mad by Borowczyk with Jan Lenica, is presented with an optional audio commentary by the recently deceased art historian Szymon Bojko, a friend and collaborator of Borowczyk’s. Bojko’s comments are in Polish, with optional English subtitles; o ‘Dom’ (11:27). As the introduction to this short animated film suggests, there are plentiful similarities between this film and, say, the films of Man Ray and Hans Richter. This short film has an optional audio commentary by Wodzimierz Kotonski. Kotonski speaks in Polish, with optional English subtitles; o ‘The School’ (7:24). This fascinating short film, the only short animation Borowczyk made in Poland in which he didn’t share the directing credit with Jan Lenica, is almost entirely constructed from still frames, with editing used to create a sense of movement. The short film is accompanied by an optional commentary with Daniel Bird. - ‘Miscellaneous’ (7:05). This video essay focuses on Borowczyk’s work with Jan Lenica on newsreel films and documentaries. - ‘Street Art’ (11:34). This vintage newsreel piece focusing on the history and art of the poster was co-written by Borowczyk. It opens with a man pasting posters to a hoarding, then a narrator explores the dominant paradigms of these posters. The narration is in Polish, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Tools of the Trade’ (6:24). Here, the son of photographer Wojciech Zamecznik, Juliusz Zamecznik, exhibits the camera used by Borowczyk and Lenica during the shooting of ‘Once Upon a Time’. Zamecznik speaks in English. - ‘Poster Girl’ (4:05). Teresa Byszewska, a poster artist and illustrator, discusses the working relationship between Borowczyk and Jan Lenica. Byszewska speaks in Polish, with optional English subtitles.

Overall

As ironic as the opening sequence might be, with Jutkiewicz’ words of warning to Ewa that she should turn her eyes away from sin acting also as an ironic ‘promise’ to the audience of the earthly delights that are to follow, as its narrative progresses The Story of Sin depicts Ewa’s spiral into lust and murder which is accompanied by the gradual stripping away of the promise of redemption – and driven by a persistent theme of loss (of innocence, of Ewa’s love Lukasz, of the baby). Borowczyk’s scorn is saved for the men (and occasional woman) who precipitated Ewa’s descent into sin, from the overtly villainous Horst and Plaza-Splawski to the subtle but more insidious villainy of Lukasz and Bozanta. It’s a story of hypocrisy that targets the family, patriarchy and the Church, making it a superb companion piece to Borowczyk’s The Beast. The comparisons often made with narratives such as Cleland’s Fanny Hill, de Sade’s Justine and Juliette, and Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles are potent, but what Borowczyk brings to this story is a keen eye for period detail. The visual design of the film is filled with the bric-a-brac and attention to physical objects which defines Borowczyk’s cinema, from items of furniture (desk and chairs), costumes and items both decorative and functional (clocks and cutlery) to artworks (and especially, vintage pornography). The texture of the film is rich and cloistered, easily the equal of Borowczyk’s other films of this period. As ironic as the opening sequence might be, with Jutkiewicz’ words of warning to Ewa that she should turn her eyes away from sin acting also as an ironic ‘promise’ to the audience of the earthly delights that are to follow, as its narrative progresses The Story of Sin depicts Ewa’s spiral into lust and murder which is accompanied by the gradual stripping away of the promise of redemption – and driven by a persistent theme of loss (of innocence, of Ewa’s love Lukasz, of the baby). Borowczyk’s scorn is saved for the men (and occasional woman) who precipitated Ewa’s descent into sin, from the overtly villainous Horst and Plaza-Splawski to the subtle but more insidious villainy of Lukasz and Bozanta. It’s a story of hypocrisy that targets the family, patriarchy and the Church, making it a superb companion piece to Borowczyk’s The Beast. The comparisons often made with narratives such as Cleland’s Fanny Hill, de Sade’s Justine and Juliette, and Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles are potent, but what Borowczyk brings to this story is a keen eye for period detail. The visual design of the film is filled with the bric-a-brac and attention to physical objects which defines Borowczyk’s cinema, from items of furniture (desk and chairs), costumes and items both decorative and functional (clocks and cutlery) to artworks (and especially, vintage pornography). The texture of the film is rich and cloistered, easily the equal of Borowczyk’s other films of this period.

Arrow Academy’s new Blu-ray release is profoundly welcome, a big upgrade from the film’s previous DVD releases. The new subtitle translation is superb, and the presentation of the main feature is very impressive. The film itself is accompanied by some superb contextual material. An essential release, The Story of Sin sits comfortably alongside Arrow’s previous Blu-ray releases of Borowczyk’s other pictures. References: Bird, Daniel, 2002: Pocket Essentials Film: Roman Polanski. Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials Coates, Paul, 2005: The Red and the White: The Cinema of People’s Poland. London: Wallflower Press Mikurda, Kuba, 2015: ‘Boro: Escape Artist’. In: Kuc, Kamila, Mikurda, Kuba & Oleszczyk, Michal (eds), 2015: Boro: L'Île d'amour. Oxford: Berghahn Books: 13-47

|

|||||

|