|

|

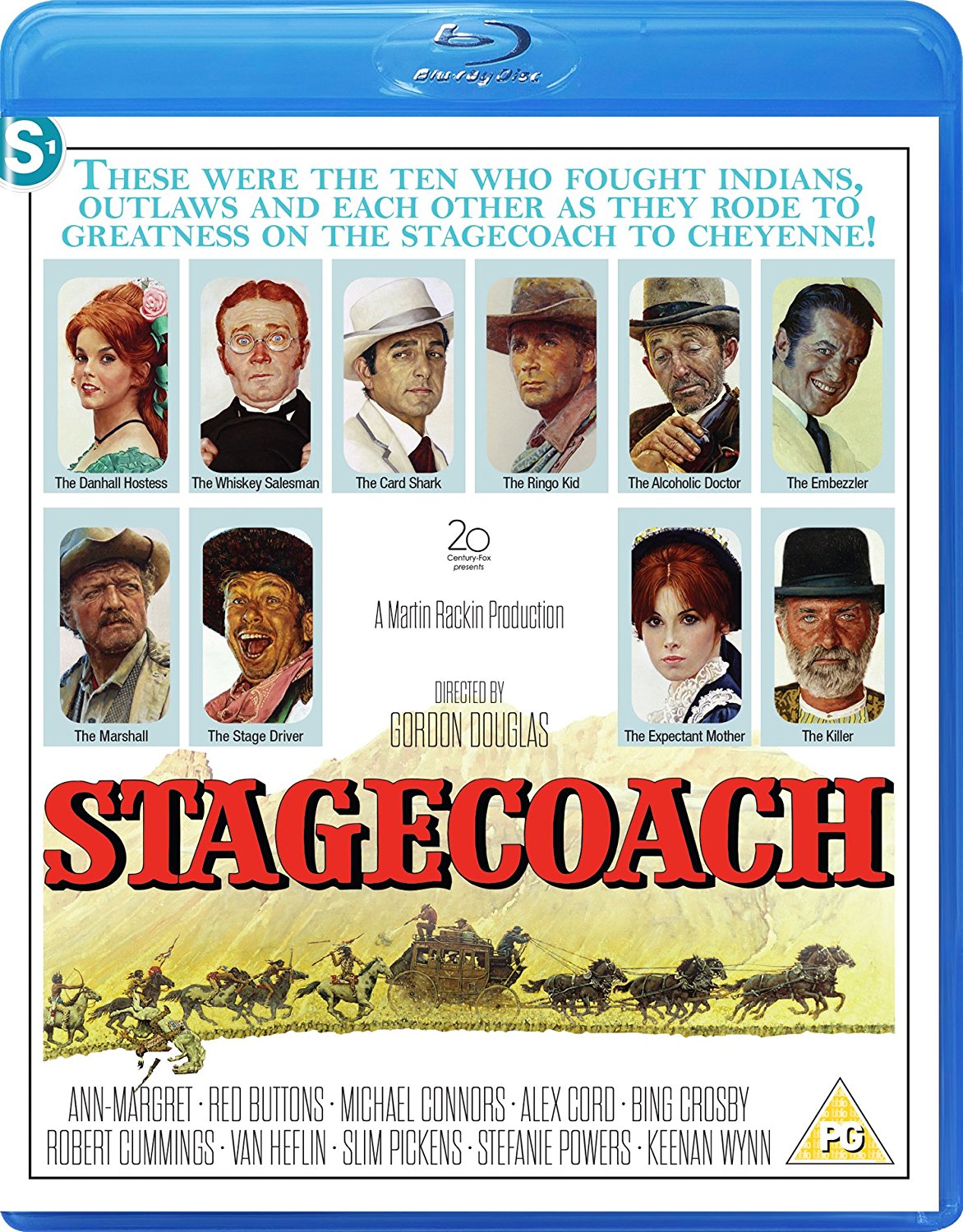

Stagecoach (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th April 2017). |

|

The Film

Stagecoach (Gordon Douglas, 1966) Stagecoach (Gordon Douglas, 1966)

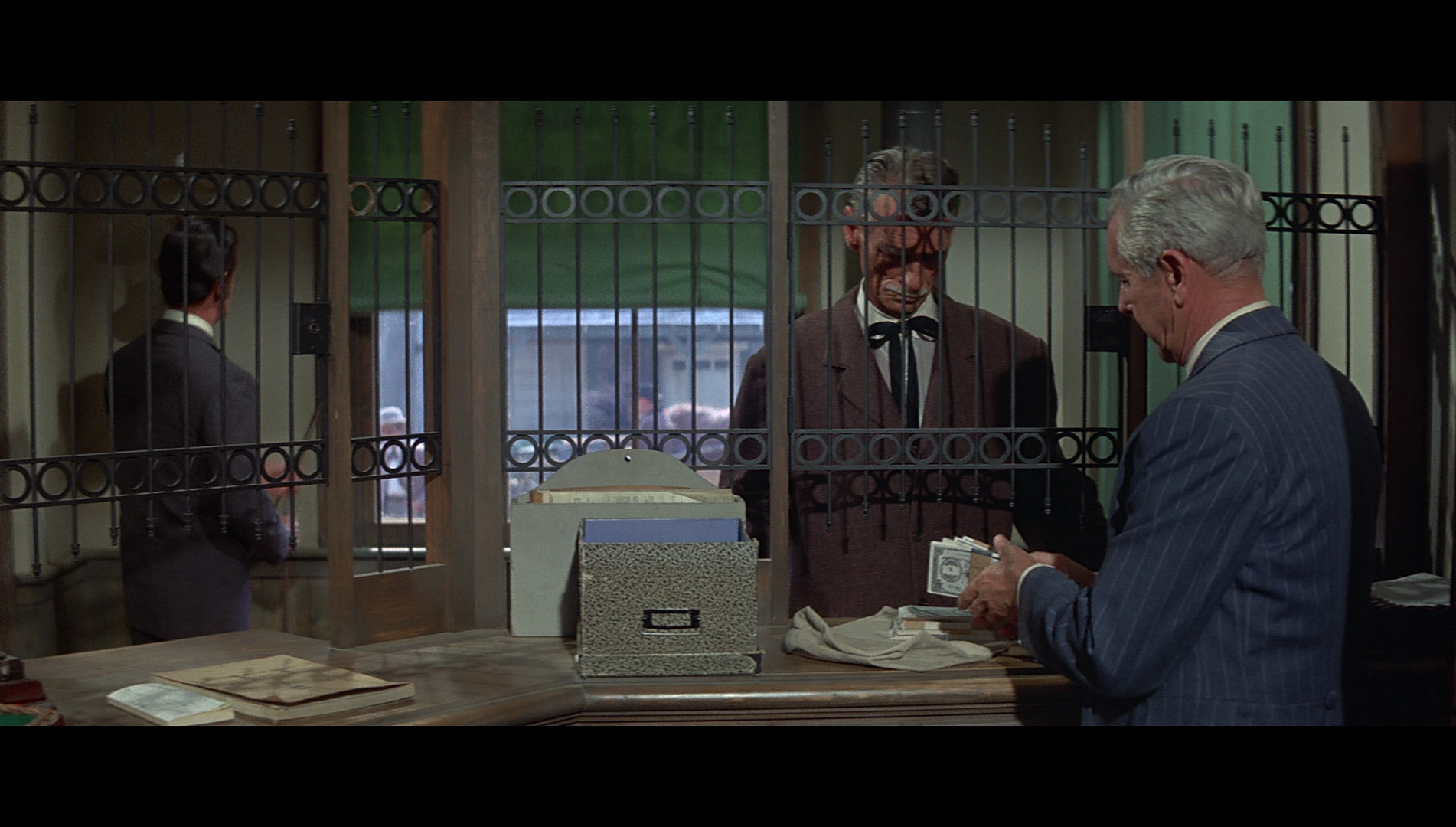

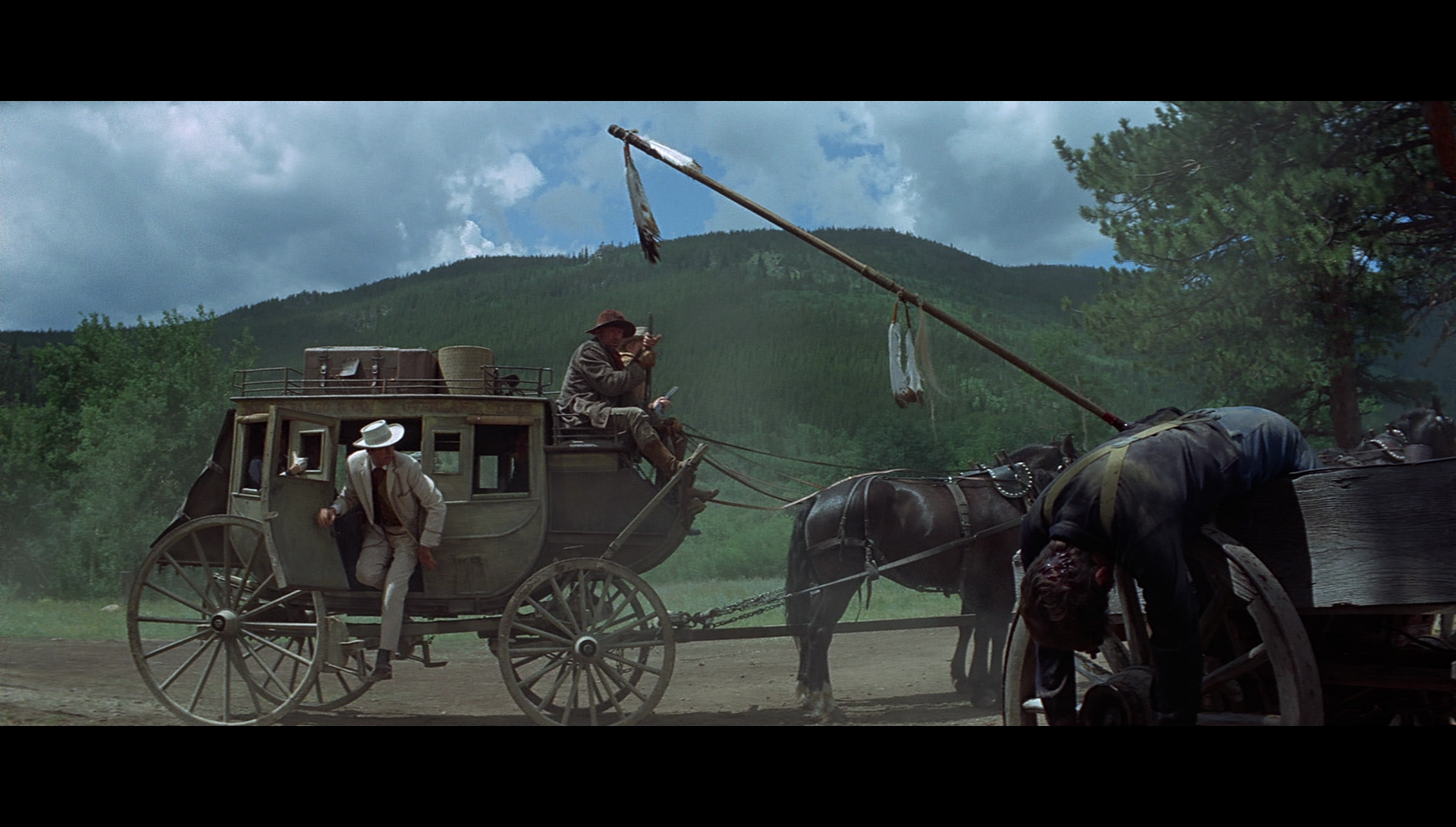

As Gordon Douglas’ Stagecoach (1966) opens, a Sioux war party is shown in the act of committing a brutal massacre at a camp of cavalry troopers. Meanwhile, in a saloon two cavalry troopers become involved in a fight over a girl, Dallas (Ann-Margret). Their commander, Captain Mallory (John Gabriel), points the finger of blame at Dallas. She is comforted by the town drunk, Josiah Boone (Bing Crosby), a former surgeon in the Union army during the Civil War. Josiah and Dallas plan to leave the town via the stagecoach to Cheyenne. Elsewhere in the town, the son of a banking family, Henry Gatewood (Robert Cummings), steals £10,000 of the bank’s money and plots to flee to Cheyenne also. As the stagecoach prepares to leave, the passengers are joined by inveterate gambler Hatfield (Mike Connors), whisky salesman Peacock (Red Buttons), and Mrs Mallory (Stefanie Powers), the pregnant wife of Captain Mallory. The stagecoach is joined by Marshal Curly Wilcox (Van Heflin), who offers to ride ‘shotgun’ alongside driver Buck (Slim Pickens). Before the stagecoach leaves, they are warned by the cavalry that a Sioux war party led by Crazy Horse is on the rampage. However, the passengers choose to take the risk and continue with their journey. The stagecoach and its passengers encounter the Ringo Kid (Alex Cord), who is wanted for murder, on a path through a forest; his horse has ‘gone lame’. The Ringo Kid is on a quest to hunt down the Plummers, who killed his father. Curly takes Ringo into custody, planning to spend the reward for capturing him on a ‘small ranch and herd of cattle’. On a dangerous cliff-edge stretch of the route, the stagecoach is halted by a fallen tree. As the rain pours down, the Ringo Kid offers to clear the path. Given a chance to escape, Ringo doesn’t take it, instead opting to help the stagecoach’s passengers progress on their path to Cheyenne.  The stagecoach arrives at a station littered with the corpses of cavalry troopers killed by the Sioux. Mrs Mallory fears her husband may be one of the dead, and against the advice of the male passengers ventures into the station itself; Captain Mallory isn’t there, but Mrs Mallory quickly goes into labour. Josiah and Dallas attend to her, assisting in the birth of the baby. Cowardly Henry presses Curly to leave them behind so that the stagecoach may continue to Cheyenne and escape the wrath of the Sioux, who he fears will return to the station. The stagecoach arrives at a station littered with the corpses of cavalry troopers killed by the Sioux. Mrs Mallory fears her husband may be one of the dead, and against the advice of the male passengers ventures into the station itself; Captain Mallory isn’t there, but Mrs Mallory quickly goes into labour. Josiah and Dallas attend to her, assisting in the birth of the baby. Cowardly Henry presses Curly to leave them behind so that the stagecoach may continue to Cheyenne and escape the wrath of the Sioux, who he fears will return to the station.

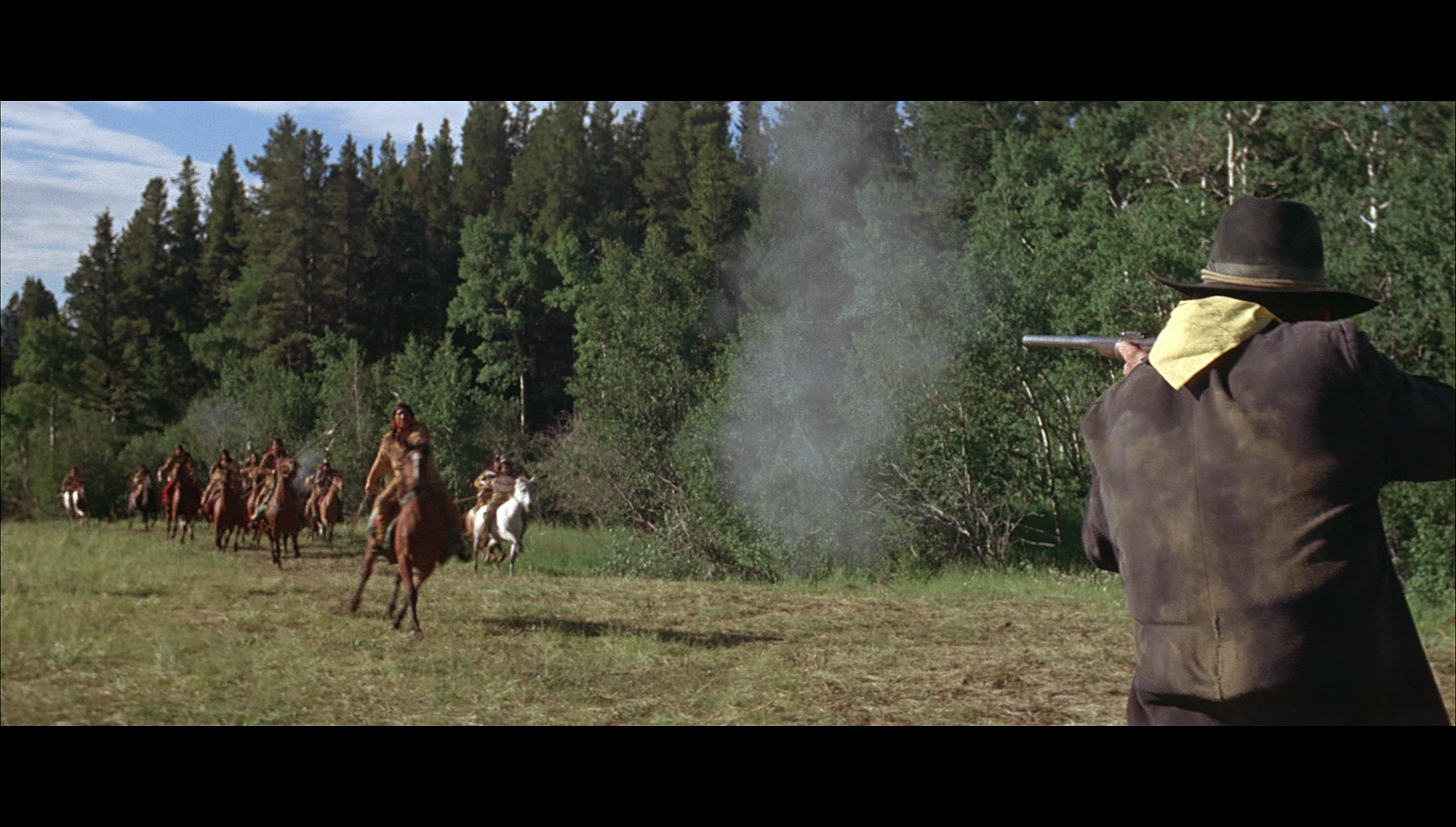

Dallas catches Henry trying to steal one of the horses; his intention is to ride the horse to his destination, though this would cripple the stagecoach. She chastises Henry but refuses to report his transgression to Curly. However, Dallas steals a gun and manages to pass it to the Ringo Kid; Ringo makes an attempt to escape, but Curly catches up to him just as a number of Sioux braves appear on the horizon. Curly gathers the group together and the stage leaves in a hurry, attempting to outrun the advancing Sioux war party. An extended chase/gunfight sequence ensues, with the Sioux attacking the stagecoach and Curly making the decision to free the Ringo Kid and arm him. Ringo proves himself to be loyal to Curly, performing several acts of bravery which save the lives of the stagecoach passengers. The stagecoach comes to a halt and is attacked a number of times by the Sioux, until finally Curly, the Ringo Kid and the others fend off the Sioux and managed to make their way to Cheyenne – where the Ringo Kid will come face to face with the Plummer family, whose services Henry has unwisely sought in his attempts to flee justice.  The word is often thrown about to such an extent that it is largely meaningless, but John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) is ‘iconic’ in the true sense of the word: Stagecoach was a technically innovative film, being the first Hollywood film to use sets with ceilings, enabling the use of low-angle camera setups and profoundly informing Orson Welles’ work on Citizen Kane less than two years later; and Ford’s picture also consolidated the narrative paradigms familiar from so many subsequent Westerns. The cavalry riding to the rescue of the stagecoach’s besieged passengers may seem like a cliché to modern audiences, but at the time Ford’s Stagecoach was originally released these supposed ‘clichés’ were new and innovative. However, when Gordon Douglas’ remake of Stagecoach appeared in 1966, the narrative template had been imitated and parodied so many times – and the genre of the Western had undergone numerous changes during the era of 1950s ‘adult Westerns’ and the revisionist Westerns that were popular throughout the 1960s – that Douglas and his crew must have struggled to come up with ways to make this so-familiar story enticing and original. (This was an even more pronounced problem in 1986, when Ted Post’s second remake of the John Ford picture was released – although that film was made in the New Hollywood era, at a time of reinvigorated interest in Westerns that had a classical structure, such as Lawrence Kasdan’s Silverado from 1985.) The word is often thrown about to such an extent that it is largely meaningless, but John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) is ‘iconic’ in the true sense of the word: Stagecoach was a technically innovative film, being the first Hollywood film to use sets with ceilings, enabling the use of low-angle camera setups and profoundly informing Orson Welles’ work on Citizen Kane less than two years later; and Ford’s picture also consolidated the narrative paradigms familiar from so many subsequent Westerns. The cavalry riding to the rescue of the stagecoach’s besieged passengers may seem like a cliché to modern audiences, but at the time Ford’s Stagecoach was originally released these supposed ‘clichés’ were new and innovative. However, when Gordon Douglas’ remake of Stagecoach appeared in 1966, the narrative template had been imitated and parodied so many times – and the genre of the Western had undergone numerous changes during the era of 1950s ‘adult Westerns’ and the revisionist Westerns that were popular throughout the 1960s – that Douglas and his crew must have struggled to come up with ways to make this so-familiar story enticing and original. (This was an even more pronounced problem in 1986, when Ted Post’s second remake of the John Ford picture was released – although that film was made in the New Hollywood era, at a time of reinvigorated interest in Westerns that had a classical structure, such as Lawrence Kasdan’s Silverado from 1985.)

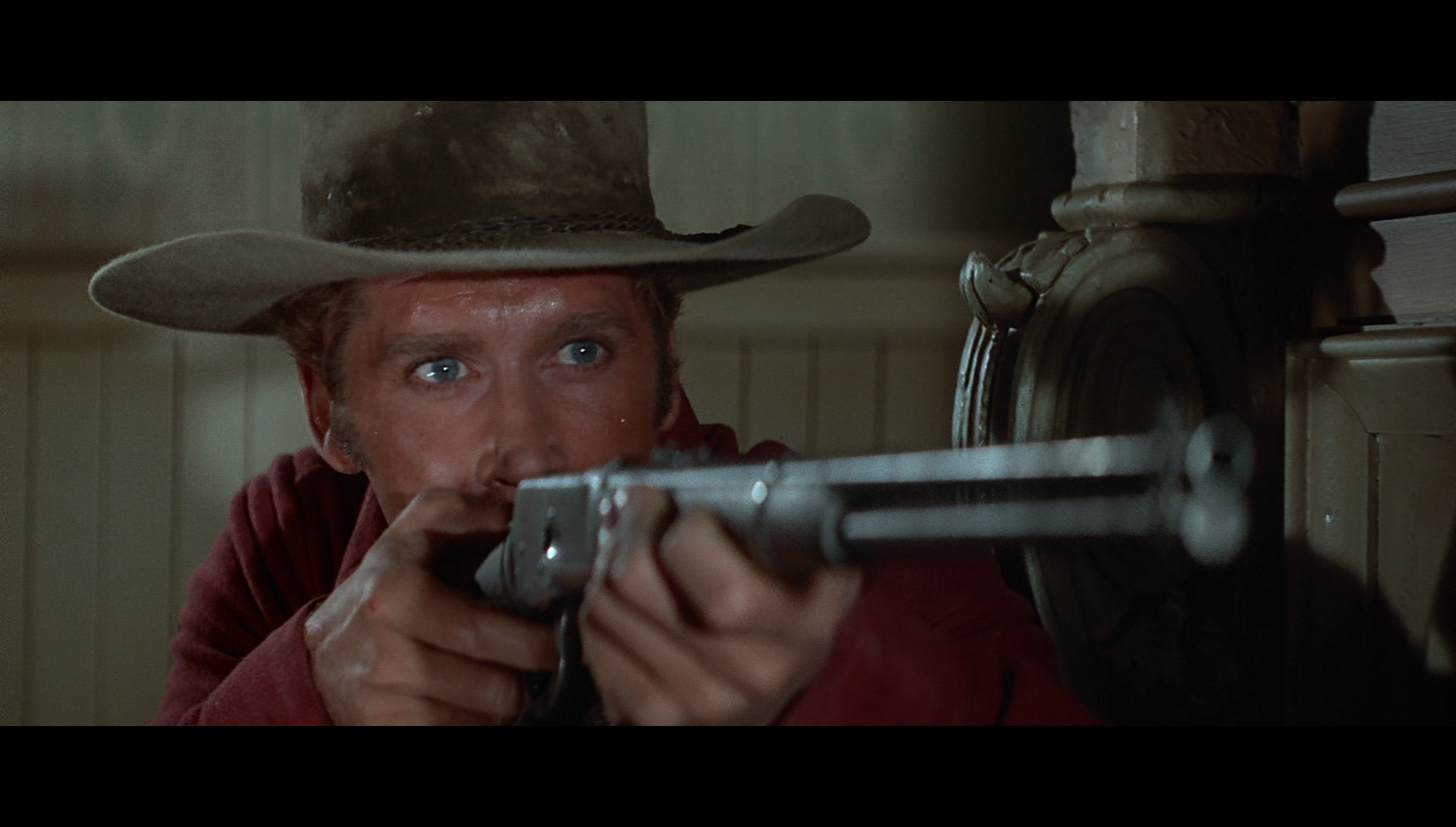

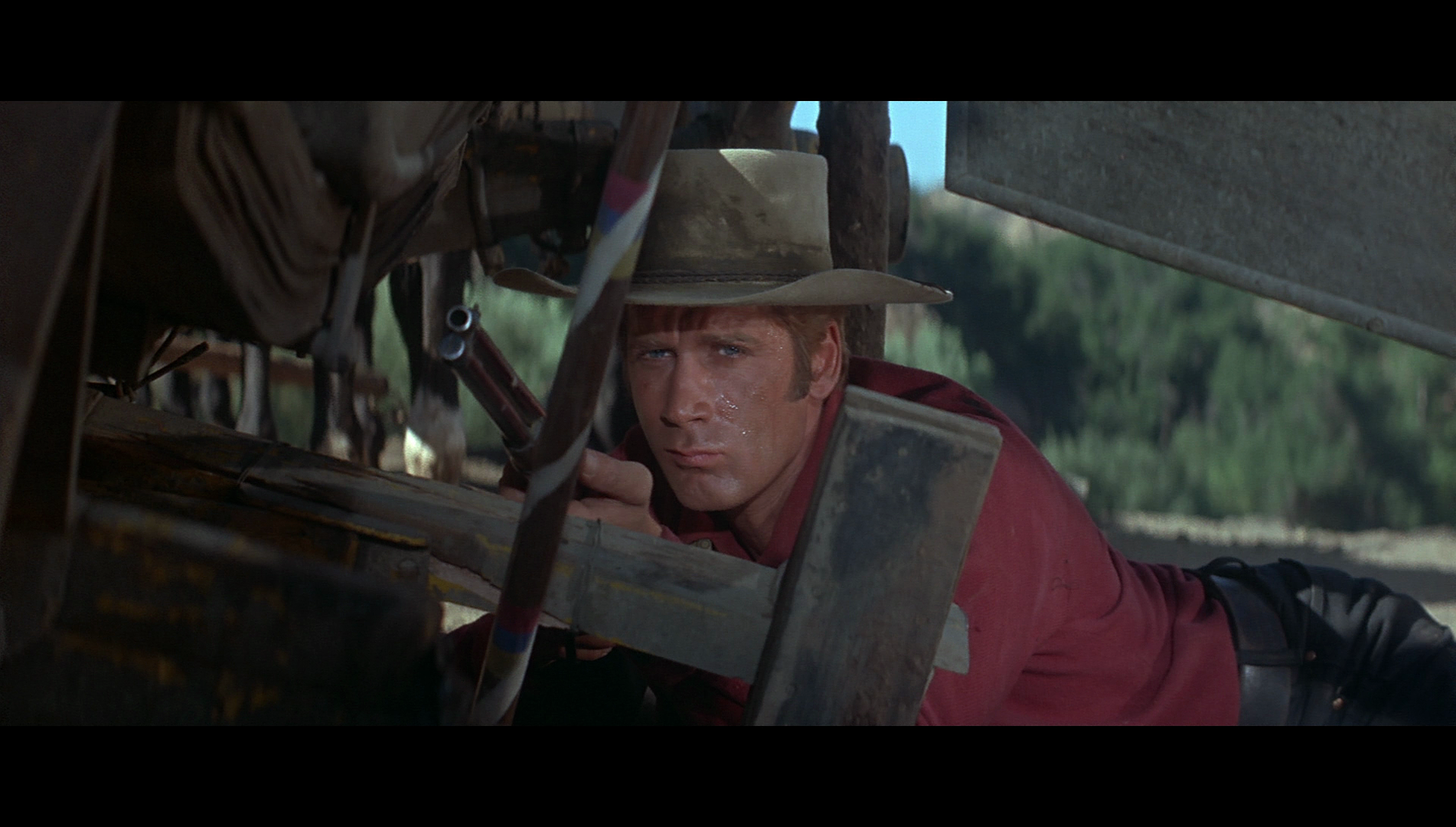

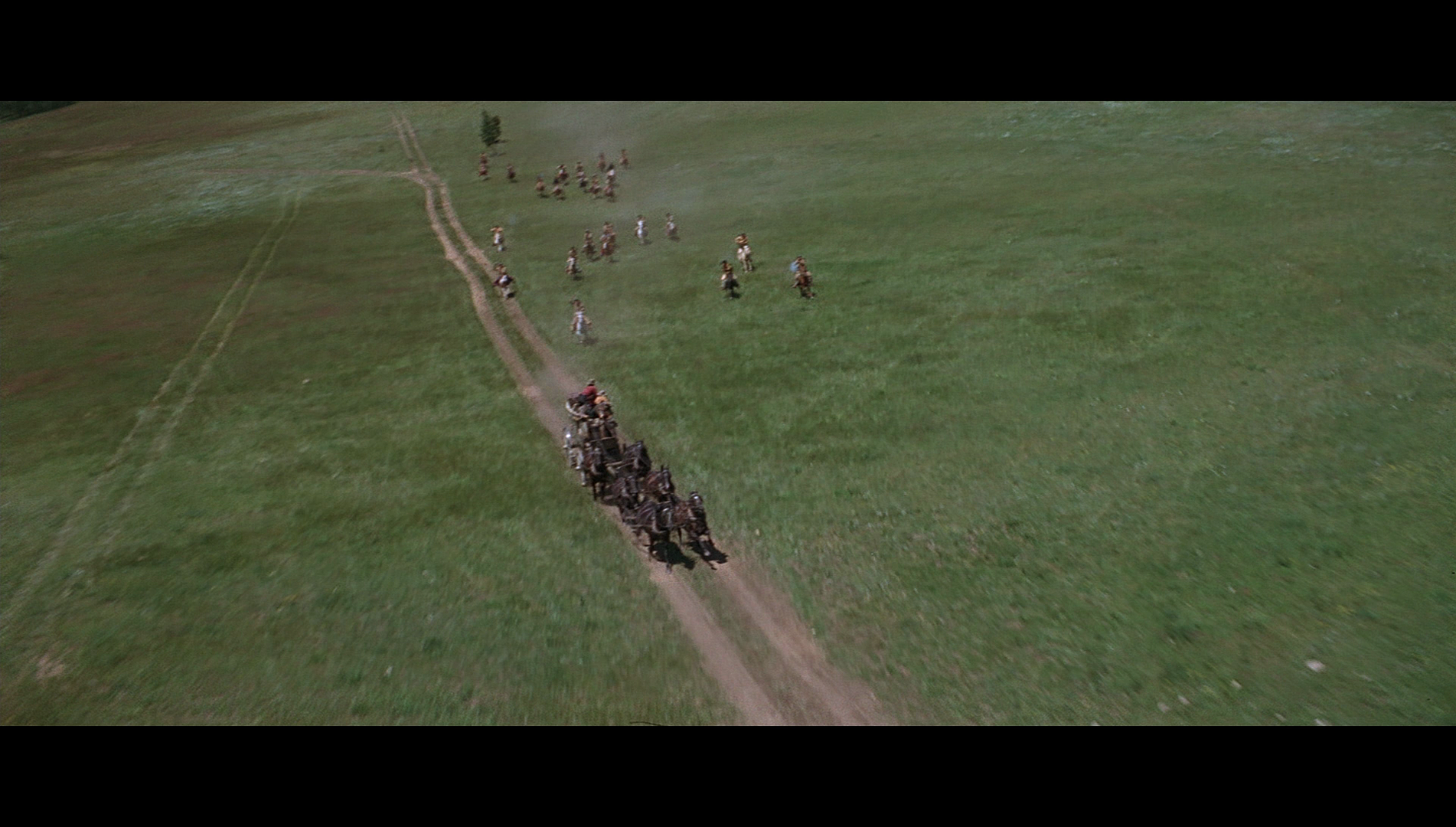

Douglas’ film does this by moving the action from the dusty, arid landscape of Arizona (the setting of Ford’s film) to the forests of Colorado, and making expressive use of widescreen colour Cinemascope photography. In an attempt at foregrounding its principal difference from Ford’s picture, Douglas’ Stagecoach signals its use of the widescreen frame with its opening moments, featuring the film’s titles playing out over sweeping helicopter shots of forested land in Colorado. The later sequence in which the Sioux war party chase the stagecoach features much use of swooping aerial shots showing both the stagecoach and the Sioux braves traversing the landscape, shooting at one another. Perhaps inspired by the westerns all’italiana/‘Spaghetti Westerns’ that had become popular with the American release of Sergio Leone’s Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964), and certainly facilitated by the relaxation of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1965 (leading to its replacement with an age-based classification system in 1968), Douglas also ups the ante in terms of violence, filling the frame with tortured and tormented bodies. The assault by a Sioux raiding party on a camp of cavalry troops which opens the picture contains some shocking violence. Spears pierce the chests of cavalry troops; tomahawks are buried in skulls (in fact, this is one of the film’s first images); horses trample over the bodies; one of the troopers is ensnared by a Sioux brave and dragged behind a horse, the brave pulling the trooper into an open fire. The violence is almost on par with the shocking violence of Soldier Blue (Ralph Nelson, 1970), though ideologically this film is the polar opposite to the later revisionist Westerns: where Soldier Blue features at its climax cavalry troops committing heinous violence against the Cheyenne and Arapaho denizens of Sand Creek (in an overt echo of the then-recent My Lai massacre), Stagecoach opens with the more conventional sight of Native Americans attacking white Americans, and for much of its running time reinforces the notion that Native Americans are inherently violent – a mysterious, unknowable force of nature that provides a constant sense of threat to the lives of the white settler community. Given the context of the film’s production, Douglas’ Stagecoach is relatively forward-thinking in the roles it gives to women but very backwards-looking in its depiction of Native Americans. The Sioux in the film are seen wholly from a distance, and in almost every scene in which the Sioux appear they rampage through the frame, wreaking havoc and committing horrendous acts of violence. The film depicts Native Americans as rampaging, untamed beasts, with none of the complexities of the revisionist Westerns that would become popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s – such as Robert Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid (1972).  The film’s moments of action are effective, the widescreen frame trapping and following the stagecoach as it is pursued across the landscape by the Sioux war party. Rifles fill the frame, Clothier breaking the long-standing taboo within Westerns of including both the man firing the rifle and his target in the same shot (in the manner of Leone’s westerns all’italiana). The Cinemascope frame allows Clothier to shoot the passengers of the stagecoach in groups of three. The film’s action setpieces are exciting, predicated on some impressive stuntwork. Notably, Douglas’ picture emulates the most famous stunt from Ford’s Stagecoach, in which Enos ‘Yakima’ Canutt dropped from a horse and allowed himself to fall between the team of horses pulling the stagecoach, passing beneath the vehicle. In Douglas’ remake, the stunt is performed by Dean Smith. (This famous stunt was emulated in the scene in Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1981, in which stuntman Terry Leonard climbed to the front of a German truck and allowed himself to be dragged beneath it.) The film’s moments of action are effective, the widescreen frame trapping and following the stagecoach as it is pursued across the landscape by the Sioux war party. Rifles fill the frame, Clothier breaking the long-standing taboo within Westerns of including both the man firing the rifle and his target in the same shot (in the manner of Leone’s westerns all’italiana). The Cinemascope frame allows Clothier to shoot the passengers of the stagecoach in groups of three. The film’s action setpieces are exciting, predicated on some impressive stuntwork. Notably, Douglas’ picture emulates the most famous stunt from Ford’s Stagecoach, in which Enos ‘Yakima’ Canutt dropped from a horse and allowed himself to fall between the team of horses pulling the stagecoach, passing beneath the vehicle. In Douglas’ remake, the stunt is performed by Dean Smith. (This famous stunt was emulated in the scene in Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1981, in which stuntman Terry Leonard climbed to the front of a German truck and allowed himself to be dragged beneath it.)

Alongside the main narrative is the Ringo Kid’s quest for revenge following the murder of his father by the Plummer family. Curly acknowledges that the Ringo Kid was always something of an outlaw, but expresses reservations about Ringo’s potential to be a cold-blooded murderer – the crime for which he is sought by the law. When the stagecoach encounters the Ringo Kid after it leaves the town and heads for Cheyenne, Curly takes Ringo into custody; however, Ringo reminds Curly of the Sioux threat and suggests he may be of help to the stagecoach and its passengers: ‘You might need me and this Winchester, Curly: I saw a couple of ranches burnin’ last night’, the Ringo Kid says. Later, when the stagecoach stops at a station, Dallas asks the Ringo Kid how he came to be in the prison from which he escaped. ‘They say I killed a man. Shot him in the back’, Ringo replies. ‘Did you?’, Dallas asks. ‘That’s what they say’, Ringo responds enigmatically. As the narrative progresses, Ringo proves himself to be indispensable, saving the stagecoach from the Sioux war party through several acts of selfless bravery. His journey to Cheyenne inevitably climaxes with a confrontation between the Ringo Kid and the Plummers, the killers of Ringo’s father.  Nevertheless, in terms of casting, Alex Cord is no substitute for John Wayne (who played the role of the Ringo Kid in Ford’s film), having neither Wayne’s imposing physical presence nor his signature cocksure drawl, and Cord’s portrayal of the Ringo Kid is perhaps where the film falters: in this remake of Ford’s picture, the Ringo Kid is relegated largely to the film’s background, allowing the other characters – especially Bing Crosby’s Josiah (this was Crosby’s last role in a feature film), who has a wonderful recurring gag in which he steals an unaware Peacock’s whisky samples, Ann-Margret’s Dallas and Van Heflin’s Curly – to take centre stage. Like Ford’s film, the defining conflict of Douglas’ Stagecoach is arguably not so much between Native American and settler groups but between the ‘respectable’ and the ‘disreputable’ characters. When, in the scene set in a saloon which follows the Sioux’s massacre of cavalry troops that opens the film, two troopers become involved in a fight over Dallas, Captain Mallory places the blame for the incident squarely on the shoulders of the disinterested Dallas. ‘She did it’, one of the other women mutters to her friend, ‘She’s always making trouble with the soldiers’. Mallory tells the saloon owner, ‘You get rid of your undesirable elements, or I’ll get rid of them for you’. After the conflict has died down, Josiah Boone sidles up to Dallas and tells her, ‘See, my dear, you and I are both victims of a disease called “social prejudice”. It makes no allowance for beauty, wit, or previous service’. Josiah is another pariah within the community, the town drunk who nevertheless demonstrated considerable skill in his tenure as an army surgeon during the Civil War. Nevertheless, in terms of casting, Alex Cord is no substitute for John Wayne (who played the role of the Ringo Kid in Ford’s film), having neither Wayne’s imposing physical presence nor his signature cocksure drawl, and Cord’s portrayal of the Ringo Kid is perhaps where the film falters: in this remake of Ford’s picture, the Ringo Kid is relegated largely to the film’s background, allowing the other characters – especially Bing Crosby’s Josiah (this was Crosby’s last role in a feature film), who has a wonderful recurring gag in which he steals an unaware Peacock’s whisky samples, Ann-Margret’s Dallas and Van Heflin’s Curly – to take centre stage. Like Ford’s film, the defining conflict of Douglas’ Stagecoach is arguably not so much between Native American and settler groups but between the ‘respectable’ and the ‘disreputable’ characters. When, in the scene set in a saloon which follows the Sioux’s massacre of cavalry troops that opens the film, two troopers become involved in a fight over Dallas, Captain Mallory places the blame for the incident squarely on the shoulders of the disinterested Dallas. ‘She did it’, one of the other women mutters to her friend, ‘She’s always making trouble with the soldiers’. Mallory tells the saloon owner, ‘You get rid of your undesirable elements, or I’ll get rid of them for you’. After the conflict has died down, Josiah Boone sidles up to Dallas and tells her, ‘See, my dear, you and I are both victims of a disease called “social prejudice”. It makes no allowance for beauty, wit, or previous service’. Josiah is another pariah within the community, the town drunk who nevertheless demonstrated considerable skill in his tenure as an army surgeon during the Civil War.

Carrying a mixture of members of ‘respectable’ society (such as thieving banker Henry Gatewood, and Mrs Mallory, the pregnant wife of the cavalry captain who expelled Dallas from the town in the film’s opening sequences) and ‘disreputable’ characters like Ringo Kid, the outlaw, and saloon girl Dallas, the stagecoach is a ‘liminal’ space that exist between the worlds of those defined as ‘deviant’ and the members of ‘straight’ society. As the narrative progresses, as in Ford’s picture, characters on both sides of the equation are allowed to transgress to the other side: respectable and upstanding Henry Gatewood is revealed to be a thief and coward, and scorned town drunk Josiah Boone sobers up and demonstrates his skills as a practising doctor during the birth of Mrs Mallory’s baby, assisted by Dallas. (‘Hurts even when you’re a lady, huh?’, Dallas quips to Mrs Mallory after the baby has been born.) Josiah’s transformation from town drunk to competent doctor is signalled by his decision to sober himself up by drinking salt water, and his command that Peacock produce his whisky samples – to pour them over Josiah’s hands. ‘It’s sterilisation: a device we army surgeons found very useful out in the field’, Josiah says as this deeply symbolic act (of cleansing and the shedding of Josiah’s past) takes place. Outlaw Ringo and saloon girl Dallas are quick to ally themselves with one another: both outcasts, they are regarded with suspicion or scorn by the more ‘respectable’ members of society such as Henry (who is, secretly, himself a coward and a thief, having stolen and fled with £10,000 from his family’s bank). ‘You’re a loser just like me’, Dallas tells Ringo just before they kiss for the first time, ‘Tell me when you ever won’. However, the changes that had taken place in American society between the production of the two films meant that this structuring conflict carries less weight in the 1966 remake: in Marked Women: Prostitutes and Prostitution in the Cinema, Russell Campbell asserts that ‘[t]he disreputable/respectable divide is again undercut in the two remakes [of Stagecoach], though it carries less weight in the more permissive climate of the times in which the later films were made’ (Campbell, 2006: 91).

Video

Taking up about 21Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc, Stagecoach is presented here uncut, with a running time of 114:04 mins. (The film has never been available on home video in the UK before; prior to this, the only UK release for this picture was the 1966 cinema release, which featured unspecified cuts by the BBFC. Those cuts have been waived here.) The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original Cinemascope ratio of 2.35:1. The presentation has the rich texture of 35mm film, something which is retained within the robust encode on this disc. Colours are vibrant and natural, with the rich yellow of the film’s opening titles set against the autumnal greens of the trees of Colorado’s forests that are featured in the aerial shots which play out underneath these titles. These shots establish the story-space of the film as vastly different from that of Ford’s original picture, which was set in Ford’s usual stomping ground of the Arizona desert. An excellent level of detail is present throughout the film, fine detail being evident especially in close-ups of actor’s faces. Sometimes the periphery of the frame loses definition, but this is most likely down to the characteristics of the Cinemascope lenses used during the mid-1960s rather than being a ‘flaw’ of this presentation. (On the same subject, there is some quite dreadful day-for-night footage about an hour into the film.) Contrast levels are excellent. Much of the film is shot in bright sunlight, and this presentation makes the most of this, balancing the highlights with some clearly-defined midtones and deep shadows. Taking up about 21Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc, Stagecoach is presented here uncut, with a running time of 114:04 mins. (The film has never been available on home video in the UK before; prior to this, the only UK release for this picture was the 1966 cinema release, which featured unspecified cuts by the BBFC. Those cuts have been waived here.) The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original Cinemascope ratio of 2.35:1. The presentation has the rich texture of 35mm film, something which is retained within the robust encode on this disc. Colours are vibrant and natural, with the rich yellow of the film’s opening titles set against the autumnal greens of the trees of Colorado’s forests that are featured in the aerial shots which play out underneath these titles. These shots establish the story-space of the film as vastly different from that of Ford’s original picture, which was set in Ford’s usual stomping ground of the Arizona desert. An excellent level of detail is present throughout the film, fine detail being evident especially in close-ups of actor’s faces. Sometimes the periphery of the frame loses definition, but this is most likely down to the characteristics of the Cinemascope lenses used during the mid-1960s rather than being a ‘flaw’ of this presentation. (On the same subject, there is some quite dreadful day-for-night footage about an hour into the film.) Contrast levels are excellent. Much of the film is shot in bright sunlight, and this presentation makes the most of this, balancing the highlights with some clearly-defined midtones and deep shadows.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is rich and free of any problems, displaying depth when it needs to (eg, when Jerry Goldsmith’s music appears, or gunshots erupt on the soundtrack). Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with screenwriter and Western historian C Courtney Joyner and Henry Parke, the Westerns film editor for True West magazine. In this commentary track, Joyner and Parke talk enthusiastically about the film, bringing to their conversation a wealth of anecdotes about the picture and a shared enthusiasm for the Western genre. They talk about the reasons why the film has largely been forgotten and reflect on the casting, especially Alex Cord’s role in the film – which Joyner suggests was an attempt to turn Cord into the ‘new Steve McQueen’. They talk about some of the changes made to the story in comparison with Ford’s original picture. - A promotional materials gallery (10 images). This gallery features the famous Norman Rockwell portraits of the film’s main cast. - A stills gallery (139 images). This gallery features behind-the-scenes shots alongside photographic portraits of the main cast and some candid shots of the cast and crew. One particularly striking photography sees Van Heflin framed within a gun barrel.

Overall

Director of photography William Clothier later asserted that John ‘Ford called me a prostitute for doing that [Douglas’ Stagecoach]’ (Clothier, quoted in Eyman, 1987: 143). Clothier argued that giving the film the same title as Ford’s iconic Western was a ‘mistake’, as this led to audiences and critics drawing direct – and unfavourable – comparisons between Douglas’ picture and the John Ford film; and ‘if they’d [the filmmakers had] called it almost anything else, it would have passed. Being STAGECOACH though, how the hell can you do it any better than it was the first time?’ (Clothier, quoted in ibid.). However, taken as a completely separate adaptation of the same source material as Ford’s picture (Ernest Haycock’s 1937 short story ‘Stage to Lordsburg’), Douglas’ Stagecoach is a reasonably entertaining and unfussy – if formulaic – Western in its own right. However, where Ford’s picture was trailblazing and set the mold for many Westerns which followed, Douglas’ Stagecoach rides on the coattails of previous Westerns – for example, mimicking the frank approach to violence of the Italian Westerns – but doesn’t contribute anything new to the genre. Director of photography William Clothier later asserted that John ‘Ford called me a prostitute for doing that [Douglas’ Stagecoach]’ (Clothier, quoted in Eyman, 1987: 143). Clothier argued that giving the film the same title as Ford’s iconic Western was a ‘mistake’, as this led to audiences and critics drawing direct – and unfavourable – comparisons between Douglas’ picture and the John Ford film; and ‘if they’d [the filmmakers had] called it almost anything else, it would have passed. Being STAGECOACH though, how the hell can you do it any better than it was the first time?’ (Clothier, quoted in ibid.). However, taken as a completely separate adaptation of the same source material as Ford’s picture (Ernest Haycock’s 1937 short story ‘Stage to Lordsburg’), Douglas’ Stagecoach is a reasonably entertaining and unfussy – if formulaic – Western in its own right. However, where Ford’s picture was trailblazing and set the mold for many Westerns which followed, Douglas’ Stagecoach rides on the coattails of previous Westerns – for example, mimicking the frank approach to violence of the Italian Westerns – but doesn’t contribute anything new to the genre.

Gordon Douglas’ Stagecoach has long been unavailable on home video formats. As a boy growing up in a household obsessed with Westerns, it remained one of my ‘great unwatcheds’ for a number of years. Now, the film has thankfully received a very pleasing home video release. The film itself may not be the best, or most innovative, picture; and it clearly pales in comparison with Ford’s original, but taken on its own terms it’s an entertaining, if formulaic, Western that features some very good performances (from the ever-dependable Van Heflin, Red Buttons, Ann-Margret and especially Bing Crosby). Signal One Entertainment’s Blu-ray release of Stagecoach features a tip-top presentation of the main feature that is accompanied by a very good audio commentary and some beautiful stills. (As a practicing photographer, I always find a good still gallery to be a delight.) This is another excellent release from Signal One, who have nary put a foot wrong. References: Campbell, Russell, 2006: Marked Women: Prostitutes and Prostitution in the Cinema. University of Wisconsin Press Eyman, Scott, 1987: Five American Cinematographers (Filmmakers, No. 17). London: The Scarecrow Press

|

|||||

|