|

|

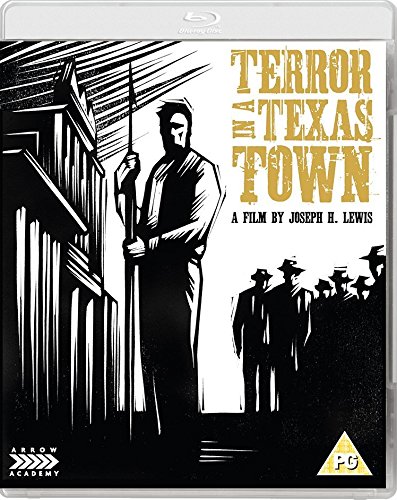

Terror in a Texas Town (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd July 2017). |

|

The Film

Terror in a Texas Town (Joseph H Lewis, 1958) Terror in a Texas Town (Joseph H Lewis, 1958)

Joseph H Lewis’ Terror in a Texas Town (1958), the final feature film of its director (who ended his career as a director of episodes of television Westerns), sits squarely within the realm of the 1950s ‘adult Western’ – Westerns that dealt with darker themes, feature conflicted protagonists and antagonists, and often amplified their violent content. As such, like other ‘adult Westerns’ of the 1950s such as Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma (1957) and Andre de Toth’s Day of the Outlaw (1959), Terror in a Texas Town sometimes resembles contemporaneous films noir. In the case of Terror in a Texas Town, the narrative and thematic similarities with the paradigms of films noir are amplified via the monochrome photography – which, like that of many films noir of the period, makes use of cluttered compositions and obtuse angles to depict a world out of kilter. Close to the Western town of Prairie City, a farm is burnt to the ground. The owner, Brady (Hank Patterson), gathers with a group of fellow farmers, including Swedish immigrant Sven Hansen (Ted Stanhope), to discuss the situation: a fat-cat landowner named McNeil (Sebastian Cabot) has been trying to acquire the land in the valley, underbuying farms where possible and, where those on the land refuse to sell, using force to coerce the farmers into abandoning their homes. However, the farmers refuse to take collective action against McNeil. When McNeil acquires the services of a notorious clad-in-black hired gun, Johnny Crale (Nedrick Young), who has a reputation for incredible violence, the ante is upped. Crale has lost his gun hand in a previous gunfight; the hand has been replaced with a steel fist. Crale conceals this appendage with a pair of black gloves, which he always wears.  Crale has brought with him his lover Molly (Carol Kelly), whose relationship with Crale is soured by his acceptance of McNeil’s contract. Molly suggests Crale should leave behind his life of violence, and even Crale himself begins to express doubts about his work as a hired killer. Crale has brought with him his lover Molly (Carol Kelly), whose relationship with Crale is soured by his acceptance of McNeil’s contract. Molly suggests Crale should leave behind his life of violence, and even Crale himself begins to express doubts about his work as a hired killer.

Meanwhile, Hansen and his Mexican neighbour Jose (Victor Millan) discover oil on their land. They reason that the presence of oil explains why McNeil is so desperate to oust the farmers from their plots. (‘Now I know why McNeil comes to our town. He don’t want our land’, Hansen tells Jose, ‘He wants our oil’.) They spot Crale approaching Hansen’s farm on horseback, and Hansen tells Jose and his young son Pepe (Eugene Mazzola) to return home. Jose refuses to leave Hansen, however, and instead of leaving he and Pepe hide in Hansen’s shed. They watch in horror as Crale guns down Hansen, who is armed with nothing more than a whaling harpoon. Jose returns with Pepe to his home, where he promises his pregnant wife Rosa (Ann Varela) not to speak of the murder of Hansen, so that their ‘child will be born in peace’. Shortly afterwards, Sven Hansen’s son George Hansen (Sterling Hayden) arrives in Prairie City. He takes a room in the hotel, where he meets Crale and Molly. Hansen is of course unaware that Crale is a hired killer. Crale tells Hansen that Hansen’s father is dead, though Crale doesn’t impart his role in the murder of Sven Hansen. George Hansen’s arrival means bad news for McNeil, however: though George hasn’t seen his father in nineteen years, owing to the fact that George has been at sea for most of his working life, he and Sven were buying the farm together: ‘Every few months I would send him a bundle of dolars. All these years I was dreaming of leaving the sea and finding a home’, George tells Crale.  McNeil attempts to pay George a pittance for the farm. George refuses to accept McNeil’s offer. He returns to the farm and meets Jose and his family. Jose gives George the whaling harpoon that belonged to Sven. Whilst at Jose’s home, George witnesses Johnny riding out to the farm and demanding that Jose and his family leave before Sunday. George realises that Johnny was the man who killed his father. McNeil attempts to pay George a pittance for the farm. George refuses to accept McNeil’s offer. He returns to the farm and meets Jose and his family. Jose gives George the whaling harpoon that belonged to Sven. Whilst at Jose’s home, George witnesses Johnny riding out to the farm and demanding that Jose and his family leave before Sunday. George realises that Johnny was the man who killed his father.

Returning to the hotel, George is humiliated and beaten by thugs in the pay of McNeil. Johnny watches on; though he doesn’t respond to Molly’s demands that Johnny stop the thugs from beating George, Johnny doesn’t participate in the beating either and looks upon it with distaste. An unconscious George is thrown onto the next train heading out of town, but when he comes to he manages to disembark from the moving train and walk back to town. Returning to Jose’s farm, George is met by Jose and Rosa. Rosa breaks her vow of silence and implores Jose to tell George why Sven was murdered: the farms are situated on oil-rich land. George rides out to tell the other farmers, but whilst he’s gone Johnny rides in to Jose’s farm and taunts Jose before killing him. However, even before he dies Jose refuses to bow down to Johnny, and Jose’s fearlessness in the face of certain death disanchors Johnny, who returns to the hotel for a confrontation with McNeil and an inevitable face-off against George. The man with the steel-hand must face the man with a whaling harpoon in the film’s ultimate showdown. Lewis is perhaps one of the most unsung directors of the post-war period, his work forever tethered to the realm of the ‘B’ movie. He began his career directing ‘B’ feature ‘singing cowboy’ films during the 1930s (his first two films as a director were Courage of the West in 1937 and The Singing Outlaw in 1938), but his postwar films became increasingly minimalist and unsentimental – almost to the point that The Big Combo (1955), often seen as Lewis’ crowning achievement, might, in its unflinching depiction of a world laced with imminent threat, be mistaken for a Sam Fuller picture. David Thomson has noted that Lewis’ films are ‘better than you will expect, adept at catching character in action, skilfully conveying underlying mood and violence while dispensing cliché plot lines’ (Thomson, 2010: np). Lewis, Thomson suggests, ‘was by instinct a visual expressionist with a subversive disregard for respectable society and a taste for sex and violence’ (ibid.). These paradigms are writ large throughout Terror in a Texas Town.  Reflecting on Terror in a Texas Town in interview with Peter Bogdanovich, Lewis stated that he was ‘fascinated with that film’, which was shot in ten days for ‘some ridiculous sum’ which Lewis remembers as being around $80,000 (Lewis, quoted in Bogdanovich, 1997: np.). Lewis committed to the film a year after he had suffered a heart attack; following his recuperation, he sought to ‘challenge myself’, and making Terror in a Texas Town within a ten day schedule was ‘a great challenge—technically, physically, everything else’ (Lewis, quoted in ibid.). Reflecting on Terror in a Texas Town in interview with Peter Bogdanovich, Lewis stated that he was ‘fascinated with that film’, which was shot in ten days for ‘some ridiculous sum’ which Lewis remembers as being around $80,000 (Lewis, quoted in Bogdanovich, 1997: np.). Lewis committed to the film a year after he had suffered a heart attack; following his recuperation, he sought to ‘challenge myself’, and making Terror in a Texas Town within a ten day schedule was ‘a great challenge—technically, physically, everything else’ (Lewis, quoted in ibid.).

Terror in a Texas Town featured a wealth of blacklisted talent, both behind the camera and in front of it. The original script had been handed to Lewis by the actor Nedrick Young, who plays gunslinger Johnny Crale in the finished picture (Lewis, in Bogdanovich, 1997: np). Whilst still blacklisted, Dalton Trumbo was offered the job of crafting Terror in a Texas Town into a complete screenplay by the film’s producer Walter Seltzer, but Trumbo instead suggested his fellow blacklistees John Howard Lawson and Mitch Lindemann. Trumbo offered his personal guarantee that the contributions of these two writers would be satisfactory. However, Seltzer approached Trumbo again following the financiers’ expression of dissatisfaction with the screenplay that had been written for the picture. Trumbo stood by his guarantee and rewrote the script within four days (see Cook, 2015). Ben L Perry was used as a ‘front’ for the film’s blacklisted writers, Trumbo and Young. Commenting on the hiring of blacklisted writers and actors, Lewis asserted that ‘I didn’t believe in what they [the House Un-American Activities Committee] were doing at that particular moment, and neither did my producer, and we both took a chance’ (Lewis, quoted in ibid.).  As the conflicted gunslinger Johnny Crale, who begins to experience doubts about his career working as a hired killer for men like McNeil, Nedrick Young – who was blacklisted for refusing to co-operate with the HUAC – is set against the film’s hero Hansen, played by Sterling Hayden – who famously ‘named names’ to the HUAC and later expressed a similar sense of regret about that decision as Crale does within the film about his work as a hired killer. Framed in this way, the final confrontation between Crale and Hansen seems openly symbolic of conflicts and debates contemporaneous to the production of the film. Jose’s refusal to give his word that he will not testify against Crale again speaks of the dilemmas within the era of the blacklist and the HUAC. Jose is aware that making promises to Crale will not save his life: Crale will kill Jose regardless of whether or not Jose promises not to testify against the gunslinger. Crale cannot comprehend the lack of fear within Jose as Jose faces his certain death: ‘You will kill me because you must kill me’, Jose asserts, ‘If I swear, you will kill me; if I agree, you will kill me; if I stand as a man, you will kill me. Well, I stand as a man’. Jose’s speech seems to directly channel the attitudes of those, such as Trumbo and Young, who refused to cooperate with the HUAC. After killing Jose, Crale returns to Molly and expresses his puzzlement at this man who refused to show fear in the face of certain death: ‘What I saw this morning was remarkable’, Johnny tells Molly, ‘Really remarkable. I saw a man that wasn’t afraid to die [….] Every man I ever held a gun on was sweating with fear. But not this one’. As the conflicted gunslinger Johnny Crale, who begins to experience doubts about his career working as a hired killer for men like McNeil, Nedrick Young – who was blacklisted for refusing to co-operate with the HUAC – is set against the film’s hero Hansen, played by Sterling Hayden – who famously ‘named names’ to the HUAC and later expressed a similar sense of regret about that decision as Crale does within the film about his work as a hired killer. Framed in this way, the final confrontation between Crale and Hansen seems openly symbolic of conflicts and debates contemporaneous to the production of the film. Jose’s refusal to give his word that he will not testify against Crale again speaks of the dilemmas within the era of the blacklist and the HUAC. Jose is aware that making promises to Crale will not save his life: Crale will kill Jose regardless of whether or not Jose promises not to testify against the gunslinger. Crale cannot comprehend the lack of fear within Jose as Jose faces his certain death: ‘You will kill me because you must kill me’, Jose asserts, ‘If I swear, you will kill me; if I agree, you will kill me; if I stand as a man, you will kill me. Well, I stand as a man’. Jose’s speech seems to directly channel the attitudes of those, such as Trumbo and Young, who refused to cooperate with the HUAC. After killing Jose, Crale returns to Molly and expresses his puzzlement at this man who refused to show fear in the face of certain death: ‘What I saw this morning was remarkable’, Johnny tells Molly, ‘Really remarkable. I saw a man that wasn’t afraid to die [….] Every man I ever held a gun on was sweating with fear. But not this one’.

To some extent, the structure of Terror in a Texas Town has parallels with that of Lewis’ previous Western The Halliday Brand (1957), the story of which is largely told in flashback. Before its opening credits, Terror in a Texas Town shows Hansen striding through the town, whale harpoon in hand, to confront Johnny Crale. Crale, whose face is not seen and is shown mostly in close-ups of his gun-hand, taunts Hansen, telling him to come closer so that he may have a better chance of spearing Crale with the harpoon: ‘You’re too far away for a fair throw, Hansen’, Crale taunts his foe, ‘Come a little closer, huh? [….] You wouldn’t want to disappoint your friends: they all came here to see blood’. Following this, the film’s opening credits play out, and the rest of the film takes place essentially as an extended flashback leading up to the climactic confrontation between the seaman and the gunslinger. The opening credits sequence features fragments of scenes that take place much later in the film’s story; Gary D Rhodes suggests that the pre-credits sequence and the footage that plays under the opening titles – ‘employ[ing] shots that will occur in later parts of the film’ – are ‘quasi-Brechtian by stimulating spectators to analyze the implications of the narrative’ (Rhodes, 2012: np). This use of Brechtian technique, Rhodes argues, was most likely intentional on the part of Trumbo and Young.  In the sequence that immediately follows the opening credits, the farm of Brady is burnt to the ground as he and his family watch on in despair. Subsequently, we see some of the farmers, including Hansen and Jose, gathered together and discussing McNeil’s attempts to take their land. Though the farmers note that ‘McNeil has stepped in and taken over half the valley’, attempting to buy land before using force to persuade those living on the land to abandon it, in their rhetoric they emphasise a response based on reciprocal reactions to the actions McNeil takes against them, an ethos that has led to a stalemate: Matt, another of the farmers, asserts that ‘If McNeil wants to fight us with the law, we’ll use the law too. If he comes at us with guns, we’ll defend ourselves’. This stalemate, it is suggested, is the reason why McNeil has called on Johnny Crale, apparently with some reluctance: a gun for hire, Crale is a symbol of an earlier time, as Molly and McNeil frequently remind him. In the sequence that immediately follows the opening credits, the farm of Brady is burnt to the ground as he and his family watch on in despair. Subsequently, we see some of the farmers, including Hansen and Jose, gathered together and discussing McNeil’s attempts to take their land. Though the farmers note that ‘McNeil has stepped in and taken over half the valley’, attempting to buy land before using force to persuade those living on the land to abandon it, in their rhetoric they emphasise a response based on reciprocal reactions to the actions McNeil takes against them, an ethos that has led to a stalemate: Matt, another of the farmers, asserts that ‘If McNeil wants to fight us with the law, we’ll use the law too. If he comes at us with guns, we’ll defend ourselves’. This stalemate, it is suggested, is the reason why McNeil has called on Johnny Crale, apparently with some reluctance: a gun for hire, Crale is a symbol of an earlier time, as Molly and McNeil frequently remind him.

The film pits a fat-cat capitalist villain against a chided immigrant hero. Even before we see McNeil, the character is suggested to be ostentatious with his wealth. At the hotel in Prairie City, a hoodlum, Baxter (Sheb Wooley), enters and regards, on the saloon counter, a platter of lobster intended for McNeil. Shorty, the bartender, tells Baxter that the lobster has been sent ‘all the way from the Gulf, packed in ice’. McNeil is soon shown in his hotel room, speaking with Johnny (who in the early part of the scene is only seen from behind). McNeil, whose corpulence signifies his greed and makes him instantly detestable, offers Johnny a flute of champagne, which Johnny drinks without removing his black gloves. ‘You realise, Johnny, that conditions have changed a great deal since you and I last worked together’, McNeil says. ‘I can see that’, Johnny replies, ‘You’ve got drapes on the doorway and lobster on the table, and seventy-five pounds more on your belly – and a new “secretary”’. ‘Your wit is as outdated as your profession, Johnny’, McNeil asserts, ‘We’ve moved into a new era. Killing on the scale you’re accustomed to isn’t fashionable anymore’. ‘As long as there are men like you, there’ll be plenty of work for me’, Johnny responds, reminding McNeil of the intimate relationship between wealth, power and the wielding of force. McNeil tells Johnny he has tried to oust the ‘squatters’ (as he calls the farmers) ‘as peacably as possible. Even paid some of them to get out’. However, he admits that he has ‘run out of means of persuasion’ and now feels that he must call on the special abilities of men like Johnny to achieve his goal. ‘Just what business are we in?’, Johnny asks. ‘My business’, McNeil responds firmly. When Johnny has left, McNeil’s ‘secretary’ observes, ‘He [Johnny] seems so strange. I’ve never met anyone like him before’. ‘That’s because you’ve never seen death walking around in the shape of a man before’, McNeil tells her.  When Johnny returns to the room he’s sharing with Molly, she tries to persuade him to leave behind his life of violence, before reminding him of how his profession is now largely redundant. ‘It’s not that kind of business again, is it?’, she asks upon seeing the money McNeil has given to Johnny, ‘Your big days are all over. One man with a gun just can’t make it anymore [….] You just can’t walk into a town and walk out of it the way you used to’. Meanwhile, Johnny treats Molly coldly, telling her that she ‘thinks of only one thing’ and, when he tires of her conversation, cruelly demanding that she ‘Shut up and get back in bed’. ‘If you’d only let me belong’, Molly protests. ‘You’re where you belong right now’, Crale answers sharply, referring to her position on the bed. When Johnny returns to the room he’s sharing with Molly, she tries to persuade him to leave behind his life of violence, before reminding him of how his profession is now largely redundant. ‘It’s not that kind of business again, is it?’, she asks upon seeing the money McNeil has given to Johnny, ‘Your big days are all over. One man with a gun just can’t make it anymore [….] You just can’t walk into a town and walk out of it the way you used to’. Meanwhile, Johnny treats Molly coldly, telling her that she ‘thinks of only one thing’ and, when he tires of her conversation, cruelly demanding that she ‘Shut up and get back in bed’. ‘If you’d only let me belong’, Molly protests. ‘You’re where you belong right now’, Crale answers sharply, referring to her position on the bed.

Seemingly disgusted by McNeil, Johnny becomes visibly conflicted about his role as a hired killer. His conflicted feelings about his work are represented via shots in which he faces the camera and the audience can read his face but the other characters can’t; a similar technique was used by de Toth in Day of the Outlaw, to represent the disgust Burl Ives’ character, a disgraced cavalry officer, feels for the savage band of outlaws he leads and is forced to keep in check. When George Hansen arrives in Prairie City’s saloon and encounters Johnny and Molly for the first time, he discovers from Johnny that his father, Sven Hansen, is dead. Johnny, who the audience know has killed Sven, treats George kindly, offering to buy him a drink; something close to regret or shame plays on Crale’s face as he converses with Hansen. ‘How did he die?’, George asks Johnny. ‘Somebody shot him’, Johnny says. ‘Why would a man shoot my father?’, George asks. ‘Maybe he had a disagreement with him. Maybe he had something they wanted’, Johnny offers. ‘What kind of country is this, where a man is killed and nobody knows anything, nobody does anything?’, George asks desperately. ‘It’s the kind of country it is’, Johnny answers matter-of-factly, ‘Things like that happen here all the time’.  In its depiction of a world that is changing, where a hired killer like Johnny Crale finds himself ‘out of time’ and adrift in a new world that is dominated by rampant capitalism and greed and where institutional and financial violence has replaced the traditional showdown, Terror in a Texas Town may perhaps be considered a ‘transitional’ Western in the manner of, for example, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969). Lewis’ film depicts America as a violent place – but the violence comes from within, ordered by wealthy businessmen such as McNeil, rather than being caused by an ‘other’. As George Hansen travels to Prairie City, the stagecoach in which he rides passes a Native American village where children play peacefully. (This features one of the film’s semi-frequent uses of stock footage.) This is the film’s only depiction of Native American culture. George looks on and smiles. At this point in the narrative, violence and brutality have already been associated with the likes of McNeil and Crale, who shortly before was shown gunning down Sven Hansen in cold-blood. The moment in which Hansen spots the Native American children playing seems included with the intention of challenging the conventional representation of Native Americans as violent ‘savages’ whilst also foregrounding what the film has already depicted as the savagery associated with the white settlers. As if to underscore this, upon Hansen’s arrival in Prairie City, one of his fellow travellers asserts ‘Here we are. Prairie City. Just another name for God’s own free country’. In its depiction of a world that is changing, where a hired killer like Johnny Crale finds himself ‘out of time’ and adrift in a new world that is dominated by rampant capitalism and greed and where institutional and financial violence has replaced the traditional showdown, Terror in a Texas Town may perhaps be considered a ‘transitional’ Western in the manner of, for example, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969). Lewis’ film depicts America as a violent place – but the violence comes from within, ordered by wealthy businessmen such as McNeil, rather than being caused by an ‘other’. As George Hansen travels to Prairie City, the stagecoach in which he rides passes a Native American village where children play peacefully. (This features one of the film’s semi-frequent uses of stock footage.) This is the film’s only depiction of Native American culture. George looks on and smiles. At this point in the narrative, violence and brutality have already been associated with the likes of McNeil and Crale, who shortly before was shown gunning down Sven Hansen in cold-blood. The moment in which Hansen spots the Native American children playing seems included with the intention of challenging the conventional representation of Native Americans as violent ‘savages’ whilst also foregrounding what the film has already depicted as the savagery associated with the white settlers. As if to underscore this, upon Hansen’s arrival in Prairie City, one of his fellow travellers asserts ‘Here we are. Prairie City. Just another name for God’s own free country’.

That Hansen is an immigrant is a fact that is used against him by McNeil and his cronies. Discovering that his father has been murdered, Hansen approaches the town sheriff – who, unbeknownst to Hansen is in the pay of McNeil – and suggests that he plans to claim the farm. The sheriff attempts to dissuade Hansen from doing so. ‘I don’t want you to get into trouble’, the sheriff says. ‘Trouble?’, Hansen asks disbelievingly, ‘How can I get into trouble claiming what’s mine?’ To this, the sheriff responds fierily: ‘No foreigner’s going to come in here and tell me how to do my job’. Shortly afterwards, McNeil is shown conversing with Johnny. ‘Swedes in this country’, McNeil declares exasperatedly, ‘They come popping up like jackrabbits’.  George’s presence galvanises the people of the town. Through their fear, the farmers refused to gather together to take action against McNeil and his hired thugs. ‘People are just like any other animal’, one of the farmers observes, ‘When they get scared, they scatter’. ‘If people would only stick together, they would have a chance’, George asserts. ‘Chance at what?’, another farmer queries, ‘All they do is talk. I’d a sight rather fight all alone than count on other people’. Later, after he has been beaten and humiliated by McNeil’s goons, Hansen returns to Jose’s farm and tells his father’s friend, ‘We could turn this valley inside out if people were not afraid [….] Afraid to talk’. Hansen’s pleas for the local people to take collective action against the bullying McNeil have an obvious relevance for the era of the blacklist and the HUAC, and are comparable to Marshal Will Kane’s (Gary Cooper) attempts to persuade the townspeople to stand with him against the outlaws led by Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) in Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1953). George’s presence in Prairie City galvanises the other residents, the community gradually overcoming their fear of Crale and McNeil, the ‘white whale’ who has terrorised them. In this sense, Gary Rhodes has suggested that Terror in a Texas Town ‘depicts the symbolic closing of that particular American nightmare involving not just one man standing up against the oppressor but also a formerly terrorized population who decides that it has now had enough and unites behind someone who will champion its cause’ (Rhodes, op cit.). George’s presence galvanises the people of the town. Through their fear, the farmers refused to gather together to take action against McNeil and his hired thugs. ‘People are just like any other animal’, one of the farmers observes, ‘When they get scared, they scatter’. ‘If people would only stick together, they would have a chance’, George asserts. ‘Chance at what?’, another farmer queries, ‘All they do is talk. I’d a sight rather fight all alone than count on other people’. Later, after he has been beaten and humiliated by McNeil’s goons, Hansen returns to Jose’s farm and tells his father’s friend, ‘We could turn this valley inside out if people were not afraid [….] Afraid to talk’. Hansen’s pleas for the local people to take collective action against the bullying McNeil have an obvious relevance for the era of the blacklist and the HUAC, and are comparable to Marshal Will Kane’s (Gary Cooper) attempts to persuade the townspeople to stand with him against the outlaws led by Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) in Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1953). George’s presence in Prairie City galvanises the other residents, the community gradually overcoming their fear of Crale and McNeil, the ‘white whale’ who has terrorised them. In this sense, Gary Rhodes has suggested that Terror in a Texas Town ‘depicts the symbolic closing of that particular American nightmare involving not just one man standing up against the oppressor but also a formerly terrorized population who decides that it has now had enough and unites behind someone who will champion its cause’ (Rhodes, op cit.).

Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954), which also starred Sterling Hayden in an unconventional role, is often cited as one of the most significant 1950s Westerns in terms of the manner in which the film toys with the visual paradigms of the genre. However, Lewis’ Terror in a Texas Town is arguably equally bold in this regard – introducing a villain, gunslinger Johnny, who dresses fetishistically in black and has a replacement right hand crafted in steel; and a final gunfight which sees Hansen using a whaling harpoon instead of a gun during his showdown against Johnny. To some extent, the appearance of Johnny has some similarities with both the dandyish ‘singing cowboys’ of 1930s Westerns (of the type Lewis began his career directing) and Dirk Bogarde’s oft-discussed costume in Bogarde’s performance as the bandit Komachi in Roy Ward Baker’s later Western The Singer Not the Song (1961). Commenting on Johnny’s fetishistic attire, McNeil observes, ‘You’ve become quite the dandy, haven’t you, Johnny? Wearing two guns instead of one… and gloves. I never saw you wear gloves before, Johnny. Do you eat in them?’ In response, Crale tells McNeil that his right hand was blown off in a gunfight ‘and I’ve been shooting left-handed ever since. And I use the other one to slug guys who ask too many questions’: Johnny’s right hand is now ‘the hardest fist in Texas. Made out of solid steel’. (‘Some people might take advantage of a cripple’, McNeil suggests spitefully.) Some of this imagery no doubt influenced later Westerns all’italiana/Spaghetti Westerns such as Sergio Corbucci’s Companeros (1970), in which Jack Palance’s villain wears a similar replacement hand to Johnny, and Giulio Questi’s Django Kill! (1967), which features a strikingly similar ‘fat cat’ capitalistic villain (Mr Sorrow, played by Roberto Camardiel) to Lewis’ picture and also sees its villain’s hired guns dressed in similarly fetishistic outfits to Johnny.

Video

Using the AVC codec, the 1080p presentation takes up approximately 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, with a running time of 80:40 mins, and is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Using the AVC codec, the 1080p presentation takes up approximately 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, with a running time of 80:40 mins, and is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

Filmed on 35mm monochrome stock, some of the photography in the film is striking. When, in the post-credits sequence, Brady’s farm is burnt to the ground at night, we see an elderly man and woman (who we later learn are Brady and his wife) looking on in despair, their faces framed in isolated close-ups, posed like sharecroppers in the Depression-era photographs of FSA photographers such as Arthur Rothstein and Walker Evans. Later, after Jose’s death his family are shown in mourning, three faces in profile seemingly shot in natural light. For a quickly-shot, cheaply-made ‘B’ feature, the film’s photography is very impressive. For this presentation, the film has been restored in 2k from a fine grain positive. The original film is a hodgepodge of different materials: stock footage (of varying qualities and using monochrome stocks with very different characteristics) totalling probably around ten minutes in length is interspersed throughout the film, and this material (such as the aforementioned shot of the Native American village that Hansen sees as he travels to Prairie City) looks in much rougher shape than the main feature. Elsewhere, some shots look soft and feature an amplified grain structure – as if they are optical ‘blow-ups’, which they may well be. Here and there, some noticeable damage is present – notably what seems to be moisture damage to the film’s negative (at 41:08, for example). Some large screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review; the first two of these screen grabs illustrate the qualities of what seem to be the ‘blow-ups’ that appear intermittently throughout the film and the presence of moisture damage, respectively. Nevertheless, though this damage is present at certain points, it’s organic to the original material and isn’t distracting. Although the source is a fine-grain positive, the fact that a positive (rather than negative) source has been used for the restoration is noticeable: the grain structure is a little coarser than a negative source would allow, and the contrast is a little sharper in its curves. These issues aside, this is an excellent presentation. The image is crisp and detailed throughout, with plenty of fine detail present – certainly much more than was present in the film’s DVD releases. Taking into account the fact that the presentation uses a positive rather than negative source, resulting in sharper curves and noticeably deeper blacks in which detail is slightly ‘crushed’ at times, contrast levels are very good – midtones have a strong sense of definition, with good gradation in the tones, and highlights never ‘bloom’. The presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, and this is carried by a solid encode to disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The track is clean and clear throughout, though quite bassy at times. The subtitles are easy to read and free from errors. The dialogue often features repetition, conversations between characters becoming fixed on specific rhetorical devices and strategies. Gary Rhodes has suggested that the repetition of certain lines in the script recalls both Lewis’ previous picture The Halliday Brand and ‘also rhetorical devices used in scripts by Abraham Polonsky and others during the blacklist era attempting to incorporate dramatic aspects of classical verse into Hollywood genres’ (Rhodes, op cit.).

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Introduction by Peter Stanfield’ (13:10). Here, Stanfield, who teaches film studies at the University of Kent, considers Lewis’ career and suggests that unlike his contemporaries, such as Sam Fuller, Douglas Sirk and Budd Boetticher, the films of Joseph H Lewis aren’t coherent and therefore Lewis can’t be considered an auteur in the true sense. Stanfield quotes Jim Kitses’ assertion, in Horizons West, that Lewis is ‘a stylist without a theme’. For Stanfield, Lewis is ‘an intuitive director’ who ‘is just responding to whatever […] is on the page, in the script’. Stanfield argues that Terror in a Texas Town is authored more by its context within the era of the blacklist than by its director. Stanfield’s comments are supported visually with the beautiful behind-the-scenes photographs. - ‘A Visual Analysis’ (14:14). This ‘video essay’ narrated by Stanfield fixes on Kitses’ argument that Lewis is ‘a stylist without a theme’. Stanfield attempts to prove this via close analysis of a series of specific moments from the film. He discusses the repetition of moments and the use of stock footage within the film, and suggests that the picture had a strong influence on Sergio Leone. (The same could be said of Sam Fuller’s extraordinary Forty Guns, released just a year prior to Terror in a Texas Town and no less ‘unusual’ in its approach to the structuring paradigms of the Western.) I was pleased to see Stanfield highlight the ways in which the photography channels some of the work of the FSA photographers, something I had notice previously; Stanfield’s comments confirmed my own feelings about this issue. - The film’s trailer (1:55). Retail copies include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet containing a new piece about the film by Glenn Kenny.

Overall

An excellent film that challenges the limits of the American Western, Terror in a Texas Town sits alongside Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar, Sam Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957) and Marlon Brando’s later One-Eyed Jacks (1961) in its incorporation of some bold and outrageous symbolism, and some complex characters and motivations that speak volumes about the qualities of the ‘adult Westerns’ (or ‘psychological Westerns’) of the 1950s. Arguably, Lewis’ film is the equal of those lofty peers – not to mention Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma and Andre de Toth’s bleak Day of the Outlaw. As in the best of Lewis’ films, Terror in a Texas Town features some bold discussion of sexuality and a handful of very stark scenes of violence. In particular, Johnny’s murder of Jose sees Johnny shoot Jose before emptying his gun into the corpse of the poor farmer, all under the gaze of Jose’s young son Pepe. An excellent film that challenges the limits of the American Western, Terror in a Texas Town sits alongside Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar, Sam Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957) and Marlon Brando’s later One-Eyed Jacks (1961) in its incorporation of some bold and outrageous symbolism, and some complex characters and motivations that speak volumes about the qualities of the ‘adult Westerns’ (or ‘psychological Westerns’) of the 1950s. Arguably, Lewis’ film is the equal of those lofty peers – not to mention Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma and Andre de Toth’s bleak Day of the Outlaw. As in the best of Lewis’ films, Terror in a Texas Town features some bold discussion of sexuality and a handful of very stark scenes of violence. In particular, Johnny’s murder of Jose sees Johnny shoot Jose before emptying his gun into the corpse of the poor farmer, all under the gaze of Jose’s young son Pepe.

Terror in a Texas Town seems openly allegorical of the era of its production, the presence both in front of the camera and behind it of personnel affected by the blacklist and the activities of the HUAC highlighting the film’s relationship with its immediate social context – though its examination of immigration, prejudice and the association of power and violence seems as relevant today as it must have done in the late 1950s. The presentation of the main feature is excellent. Some damage is present, and the restoration is from a positive rather than negative source, but regardless the final product is natural and film-like, free from harmful digital tinkering. It’s certainly a more impressive home video presentation than the film has had previously. This pleasing presentation is accompanied by a couple of insightful video extras featuring comments from Peter Stanfield and one of Arrow’s typically lush booklets. I’m a fan of Lewis’ films and 1950s Westerns, and this release is one of the most pleasing Blu-ray releases that I’ve encountered this year (and will no doubt feature on my personal ‘top ten’ of 2017), but even those with only a passing interest in the director or genre (or for that matter, how American films confronted the era of the blacklist) will find this release to be a very worthy purchase. Nice work, Arrow! References: Bogdanovich, Peter, 1997: Who the Devil Made It. New York: Ballantine Books Cook, Bruce, 2015: Trumbo: A Biography of the Oscar-Winning Screenwriter Who Broke the Hollywood Blacklist. London: Hachette Rhodes, Gary D, 2012: The Films of Joseph H Lewis. Wayne State University Press Thomson, David, 2010: The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. London: Hachette (Fifth Edition) Optical ‘blow-up’?

Moisture damage

|

|||||

|