|

|

Pulse AKA Kairo AKA The Circuit (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th July 2017). |

|

The Film

Kairo / Pulse / Circuit (Kurosawa Kiyoshi, 2001) Kairo / Pulse / Circuit (Kurosawa Kiyoshi, 2001)

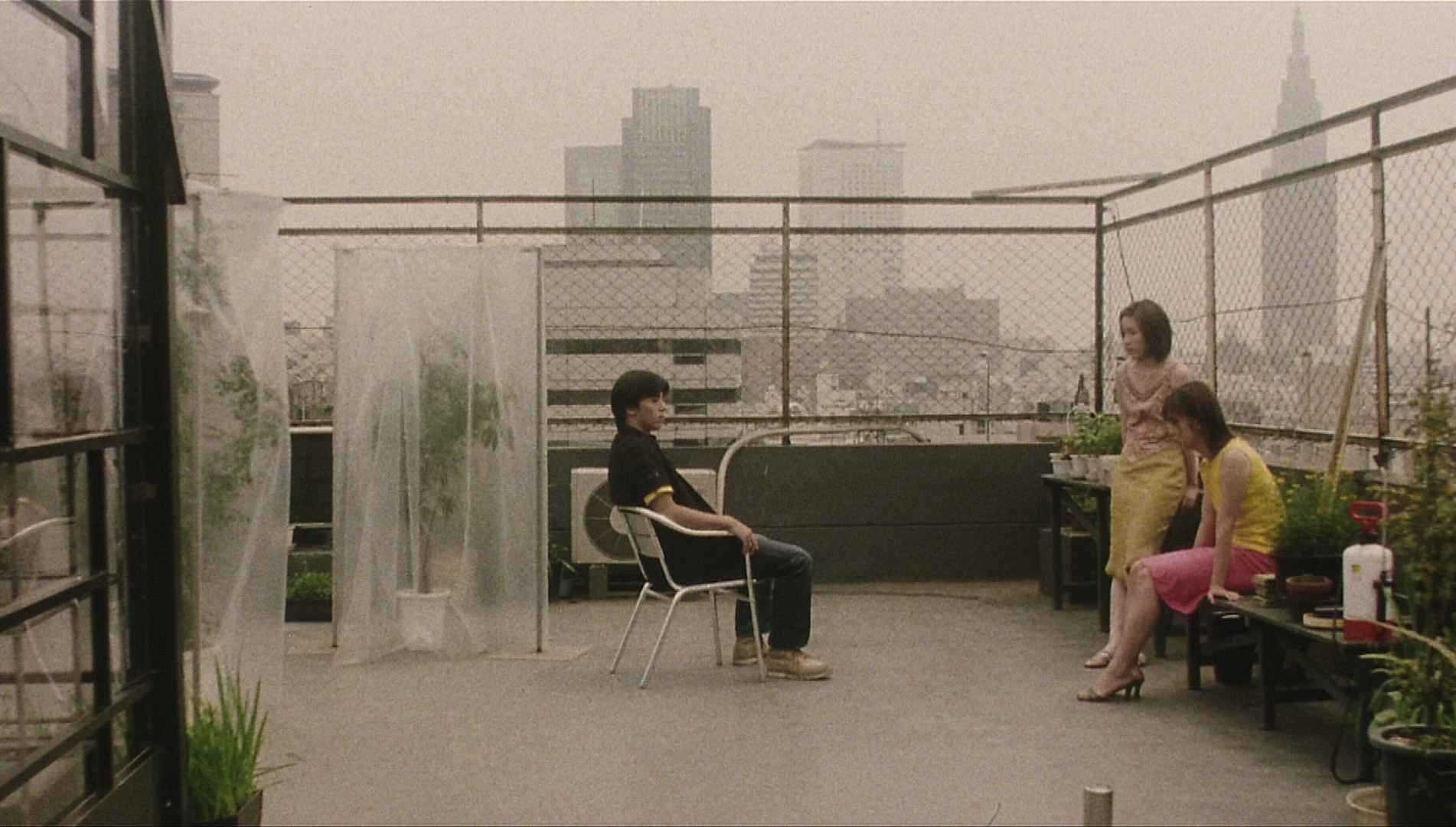

Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Kairo (known in English as Pulse, the title under which it has been released on this new Blu-ray from Arrow Video, and also as Circuit) was one of the most interesting films within the boom in ‘J-horror’ films that took place in the late 1990s and early 2000s, following the international successes of films such as Nakata Hideo’s The Ring (1998), Miike Takashi’s Audition (1998) and Shimizu Takashi’s Ju-On: The Grudge (2002). Like those films, Pulse was subjected to an American remake (in 2006, directed by Jim Sonzero). Pulse also saw an unofficial remake in Turkey (D@bbe, directed by Hasan Karacag), released the same year as the US remake. Pulse tells the parallel narratives of two young people, Michi and Kawashima. These two narratives converge as the film moves towards its climax. The story opens on a ship at sea, where Michi (Aso Kumiko) stands at one of the handrails, gazing out to sea. ‘It all began suddenly, without warning’, she says in voiceover. The rest of the film is presented as an extended flashback. Michi works in a rooftop greenhouse in Tokyo, with her friends and colleagues Junko (Arisaka Kurume) and Yabe (Matsuo Masatoshi). The trio are concerned about their other colleague Taguchi (Mizuhashi Kenji), who they have not seen for a week: Taguchi has apparently working at home on producing some software for the greenhouse. The deadline for the software looming, Michi decides to visit Taguchi at home – to both ensure her friend is okay and to acquire the disc on which he has been working so that the group may meet their deadline.  Michi enters Taguchi’s seemingly deserted flat and searches for the disc. She becomes aware of someone in the room behind her: it’s Taguchi. Michi converses with Taguchi, but he behaves strangely. She leaves him alone and continues to search for the disc. She returns to the room where she left Taguchi and discovers his corpse: he has apparently committed suicide by hanging. Michi enters Taguchi’s seemingly deserted flat and searches for the disc. She becomes aware of someone in the room behind her: it’s Taguchi. Michi converses with Taguchi, but he behaves strangely. She leaves him alone and continues to search for the disc. She returns to the room where she left Taguchi and discovers his corpse: he has apparently committed suicide by hanging.

Michi cannot understand why Taguchi would kill himself. She investigates the disc she found in his flat and discovers it contains a strange photograph of Taguchi standing next to his computer, on which is displayed the exact same image – like an infinite mirror. At home, Michi discovers that her television has begun to suffer from some strange interference; this makes her uneasy. Meanwhile, elsewhere in the city Kawashima (Kato Haruhiko), a student of economics at the university, decides to connect to the Internet using a dial-up modem and a start-up disc from an ISP that he has recently bought. Once connected, he finds his computer screen is filled with a strange sight: a series of videos of people alone in their homes. This is followed by a question, presented as text on the screen: ‘Do you want to meet a ghost?’ Unnerved, Kawashima shuts down his computer and goes to sleep. However, he is awoken when the computer switches itself on and connects to the Internet automatically, loading up the strange webpage Kawashima saw previously. At the university, Kawashima asks the computer students about his experiences. He is advised by Harue (Koyuki) that if his computer should do the same thing again, he should make a record of the web address or use the print screen key to capture the details of the webpage.  After receiving a telephone call in which Taguchi repeatedly whispers ‘Help’, Yabe travels to Taguchi’s flat and discovers a piece of paper on which is written the phrase ‘The Forbidden Room’. Yabe notices that the wall against which Taguchi’s body was found is stained a deep black. Yabe prepares to leave the flat but, before exiting, decides to return to the room in which his friend died. He is shocked to see Taguchi standing in the corner. However, Taguchi disappears suddenly. After receiving a telephone call in which Taguchi repeatedly whispers ‘Help’, Yabe travels to Taguchi’s flat and discovers a piece of paper on which is written the phrase ‘The Forbidden Room’. Yabe notices that the wall against which Taguchi’s body was found is stained a deep black. Yabe prepares to leave the flat but, before exiting, decides to return to the room in which his friend died. He is shocked to see Taguchi standing in the corner. However, Taguchi disappears suddenly.

Nearby, Yabe finds a room sealed with electrical tape. He enters it. In the room is nothing but a sofa. Yabe approaches the sofa and turns around. He is shocked to see an apparition slowly creep out of the shadows near the doorway and approach him. Yabe hides behind the sofa, but the apparition draws nearer… The next day, at work, Michi notes that Yabe is behaving strangely – avoiding conversation and looking increasingly glum. Michi presses Yabe to tell her what is wrong; he warns her enigmatically about ‘The Forbidden Room’. ‘Is that the room with the red tape?’, she asks. ‘Don’t dare to go in there’, he tells her. Kawashima and Harue become friends. Harue tells Kawashima of a computer programme created by one of her graduate students. The programme simulates human society: it depicts a series of dots which are attracted and repelled by one another. However, Harue has noticed that, mysteriously, some new, ghostly dots have appeared in the programme. Harue introduces Kawashima to one of her students, Yoshizaki (Takeda Shinji), who has some theories about what is happening which he shares with Kawashima.  Meanwhile, Michi discovers that Yabe has suffered a similar fate to Taguchi. Junko is also behaving strangely. Michi takes Junko home with her, caring for her friend. However, Junko eventually succumbs to a similar fate to Yabe and Taguchi. Michi is left alone. When Kawashima’s friend Harue disappears also, he takes refuge on the city streets, where he meets Michi; together, Michi and Kawashima make plans to flee the city. Meanwhile, Michi discovers that Yabe has suffered a similar fate to Taguchi. Junko is also behaving strangely. Michi takes Junko home with her, caring for her friend. However, Junko eventually succumbs to a similar fate to Yabe and Taguchi. Michi is left alone. When Kawashima’s friend Harue disappears also, he takes refuge on the city streets, where he meets Michi; together, Michi and Kawashima make plans to flee the city.

Director Kurosawa Kiyoshi had previously achieved some acclaim as the director of Cure (1997), a potent fusion of horror and neo-noir. Cure was notable for channelling a strong sense of the uncanny, something Kurosawa’s subsequent horror films perfected (and which continues in the non-horror pictures Kurosawa has directed since, such as Tokyo Sonata in 2008), and for refusing to offer explanations to many of the situations depicted within its narrative. Cure also made notable use of space, rendering many of the environments depicted within the film ambiguously – as if they might be products of the characters’ imaginations or taken as an externalisation of interior states. This is something that is also present within Pulse, especially in the film’s depiction of ‘The Forbidden Room’. Pulse channels the characteristics of many ‘J-horror’ films: Chika Kinoshita describes these as ‘the low-key production of atmospheric and psychological fear, rather than graphic gore, capitalizing on urban legends proliferated through mass media and popular culture (Kinoshita, 2010: 104). Kinoshita argues that the directors associated with J-horror were of a similar age and cited influences including European and American directors of horror films (specifically, Mario Bava, John Carpenter and Tobe Hooper) alongside and interest in horror-themed manga by writers such as Koga Shin’ichi and Yamagishi Ryoko (ibid.). The J-horror directors were ‘avid cinephiles who started off making films in college cine-clubs and had a keen interest in film history and critical theory’ (ibid.). Their styles were hammered out in V-Cinema (straight-to-video) productions before they transitioned to feature films (ibid.). Kurosawa is a slight exception, being slightly older than most of the other J-horror directors, having made horror films during the 1980s, prior to the J-horror boom (for example, Sweet Home in 1989).  Like a number of other J-horror films, Pulse examines modern technologies as conduits for the supernatural, foregrounding this when the logos of the production companies appear on the screen accompanied by the sound of a dial-up modem connecting to the Internet. Specifically, as Harue’s graduate student Yoshizaki tells Kawashima, the ghosts seem to be using technology to enter the land of the living – perhaps because their own domain is full to the brim. ‘The spirit or consciousness or soul, or whatever you want to call it, it turns out the realm they inhabit has a finite capacity’, Yoshizaki says, ‘Whether that capacity accommodates billions or trillions, eventually it will run out of space. Once it’s filled to the brim, it’s got to overflow somehow, somewhere [….] The souls have no choice but too ooze into another realm – that is to say, our world’. These ghosts began as a ‘faint presence’ but are growing stronger. ‘The circuit is now open’, Yoshizaki declares. (The thematic importance of the notion of ‘open’ and ‘closed’ circuits might suggest that Circuit is a better English-language title for the film than the more frequently used Pulse.) Like a number of other J-horror films, Pulse examines modern technologies as conduits for the supernatural, foregrounding this when the logos of the production companies appear on the screen accompanied by the sound of a dial-up modem connecting to the Internet. Specifically, as Harue’s graduate student Yoshizaki tells Kawashima, the ghosts seem to be using technology to enter the land of the living – perhaps because their own domain is full to the brim. ‘The spirit or consciousness or soul, or whatever you want to call it, it turns out the realm they inhabit has a finite capacity’, Yoshizaki says, ‘Whether that capacity accommodates billions or trillions, eventually it will run out of space. Once it’s filled to the brim, it’s got to overflow somehow, somewhere [….] The souls have no choice but too ooze into another realm – that is to say, our world’. These ghosts began as a ‘faint presence’ but are growing stronger. ‘The circuit is now open’, Yoshizaki declares. (The thematic importance of the notion of ‘open’ and ‘closed’ circuits might suggest that Circuit is a better English-language title for the film than the more frequently used Pulse.)

The use of technology to spread the supernatural ‘virus’ is similar to a number of other J-horror films. In Hakata’s The Ring, of course, the curse of Sadako is transmitted to her victims via a ‘haunted’ videocassette; in Miike Takashi’s One Missed Call (2003), the characters are terrorised by ‘haunted’ telephone calls which offer a premonition of their recipients’ deaths; Sono Sion’s Suicide Circle (2001) focuses on a spate of mysterious suicides which are orchestrated via websites, message boards and text messages. In these films, and in Pulse, a supernatural ‘virus’ is spread by new technologies. In this sense, the premise on which many of these films are based might invite comparison with the work of Nigel Kneale – in particular, his 1972 teleplay for The Stone Tape, in which scientists investigate the possibility that ‘ghosts’ may be captured and replayed like recordings on magnetic tape; Kneale’s teleplay was itself based on his earlier radio play You Must Listen, in which it is discovered that a ‘haunted’ telephone line somehow replays the final conversation to take place between a woman and a lover before she took her own life, which itself sounds like the premise of a more modern J-horror film.  When Kawashima’s computer comes alive by itself and connects to the Internet via dial-up modem, it links to the website that asks the question ‘Do you want to meet a ghost?’ The website presents video footage of people in their cramped, confined homes, lonely and seeking connection via the Internet – like Kawashima. As Kawashima tells Harue when asked why he chose to connect to the Internet, he did so because everybody else seemed to be doing it. ‘Wanted to connect with other people?’, Harue asks him. ‘Maybe, I don’t know’, Kawashima admits, ‘Everybody else is into it’. ‘People don’t really connect, you know’, Harue tells him, ‘We all live totally separately. That’s how it seems to me’. The film thus alludes to the phenomenon of the hikikomori – young people who, by choice or circumstance, become recluses, withdrawing from society and experiencing a strong sense of isolation and confinement within their lonely homes. Often, the phenomenon of hikikomori is explained as a product of Japan’s high pressure approach to education and employment, the gulf between expectations (of one’s self, parents or peers) and achievement leading young people to withdraw completely. As Harue suggests, these hikikomori are perhaps indistinguishable from ghosts. She tells Harue that since her youth, she has been afraid of the notion that ‘nothing changes with death’ and that ‘you might be all alone after death too’. In response, Kawashima reminds her that ‘we’re alive. Besides what have ghosts got to do with us?’ ‘Then who are they?’, Harue asks him, indicating towards the lonely people on the video feeds that play out on the computer monitors: ‘Are they really alive?’, she asks, ‘How are they different from ghosts? In fact, ghosts and people are the same, whether they’re dead or alive’. Loneliness seems to be a universal currency amongst the young people in Pulse. After discovering the dead body of Taguchi, Michi discusses his suicide with her friends Yabe and Junko. ‘I don’t know what he was depressed about’, Michi says, ‘He never said anything, so what could we have done?’ ‘Maybe he suddenly wanted to die’, Yabe responds, ‘I get that way sometimes. It’s so easy to hang yourself’. When Kawashima’s computer comes alive by itself and connects to the Internet via dial-up modem, it links to the website that asks the question ‘Do you want to meet a ghost?’ The website presents video footage of people in their cramped, confined homes, lonely and seeking connection via the Internet – like Kawashima. As Kawashima tells Harue when asked why he chose to connect to the Internet, he did so because everybody else seemed to be doing it. ‘Wanted to connect with other people?’, Harue asks him. ‘Maybe, I don’t know’, Kawashima admits, ‘Everybody else is into it’. ‘People don’t really connect, you know’, Harue tells him, ‘We all live totally separately. That’s how it seems to me’. The film thus alludes to the phenomenon of the hikikomori – young people who, by choice or circumstance, become recluses, withdrawing from society and experiencing a strong sense of isolation and confinement within their lonely homes. Often, the phenomenon of hikikomori is explained as a product of Japan’s high pressure approach to education and employment, the gulf between expectations (of one’s self, parents or peers) and achievement leading young people to withdraw completely. As Harue suggests, these hikikomori are perhaps indistinguishable from ghosts. She tells Harue that since her youth, she has been afraid of the notion that ‘nothing changes with death’ and that ‘you might be all alone after death too’. In response, Kawashima reminds her that ‘we’re alive. Besides what have ghosts got to do with us?’ ‘Then who are they?’, Harue asks him, indicating towards the lonely people on the video feeds that play out on the computer monitors: ‘Are they really alive?’, she asks, ‘How are they different from ghosts? In fact, ghosts and people are the same, whether they’re dead or alive’. Loneliness seems to be a universal currency amongst the young people in Pulse. After discovering the dead body of Taguchi, Michi discusses his suicide with her friends Yabe and Junko. ‘I don’t know what he was depressed about’, Michi says, ‘He never said anything, so what could we have done?’ ‘Maybe he suddenly wanted to die’, Yabe responds, ‘I get that way sometimes. It’s so easy to hang yourself’.

Brenda S Gardenour Walter has suggested that Pulse is about the manner in which, in the digital age, people may so easily seal themselves off from the rest of the world, making only virtual connections and linking with other people only in a mediate fashion, via the Internet: ‘In Kairo, the Internet is a red-taped door to an empty room inhabited by ghosts, a portal to despair and loneliness; in logging on […] we connect to a circuit of sorrows inhabited by desperate disembodied entities and disconnect from our fellow living human beings. Locking in our gray and empty dwellings like Taguchi, we seal up our windows and doors, blocking all human points of entry into our homes and lives, which leaves us with only a virtual existence though the Internet. Like the characters in the film, we disappear from the physical world and become ash, floating through the air in bits and bytes’ (Walter, 2014: np). The film fixes itself on ‘the paradox of modern connectivity […]: the Internet and social networking, much like life in modern cities, should bring people together, but instead they encourage anonymity and isolation’ (ibid.). This is a theme that has been explored in American horror films too (including, for example, Mike Costanza’s 2002 horror film The Collingswood Story, which takes place via the webcam conversations between two students; and more recently, the social media-focused horror picture Unfriended, released in 2015). Brenda S Gardenour Walter has suggested that Pulse is about the manner in which, in the digital age, people may so easily seal themselves off from the rest of the world, making only virtual connections and linking with other people only in a mediate fashion, via the Internet: ‘In Kairo, the Internet is a red-taped door to an empty room inhabited by ghosts, a portal to despair and loneliness; in logging on […] we connect to a circuit of sorrows inhabited by desperate disembodied entities and disconnect from our fellow living human beings. Locking in our gray and empty dwellings like Taguchi, we seal up our windows and doors, blocking all human points of entry into our homes and lives, which leaves us with only a virtual existence though the Internet. Like the characters in the film, we disappear from the physical world and become ash, floating through the air in bits and bytes’ (Walter, 2014: np). The film fixes itself on ‘the paradox of modern connectivity […]: the Internet and social networking, much like life in modern cities, should bring people together, but instead they encourage anonymity and isolation’ (ibid.). This is a theme that has been explored in American horror films too (including, for example, Mike Costanza’s 2002 horror film The Collingswood Story, which takes place via the webcam conversations between two students; and more recently, the social media-focused horror picture Unfriended, released in 2015).

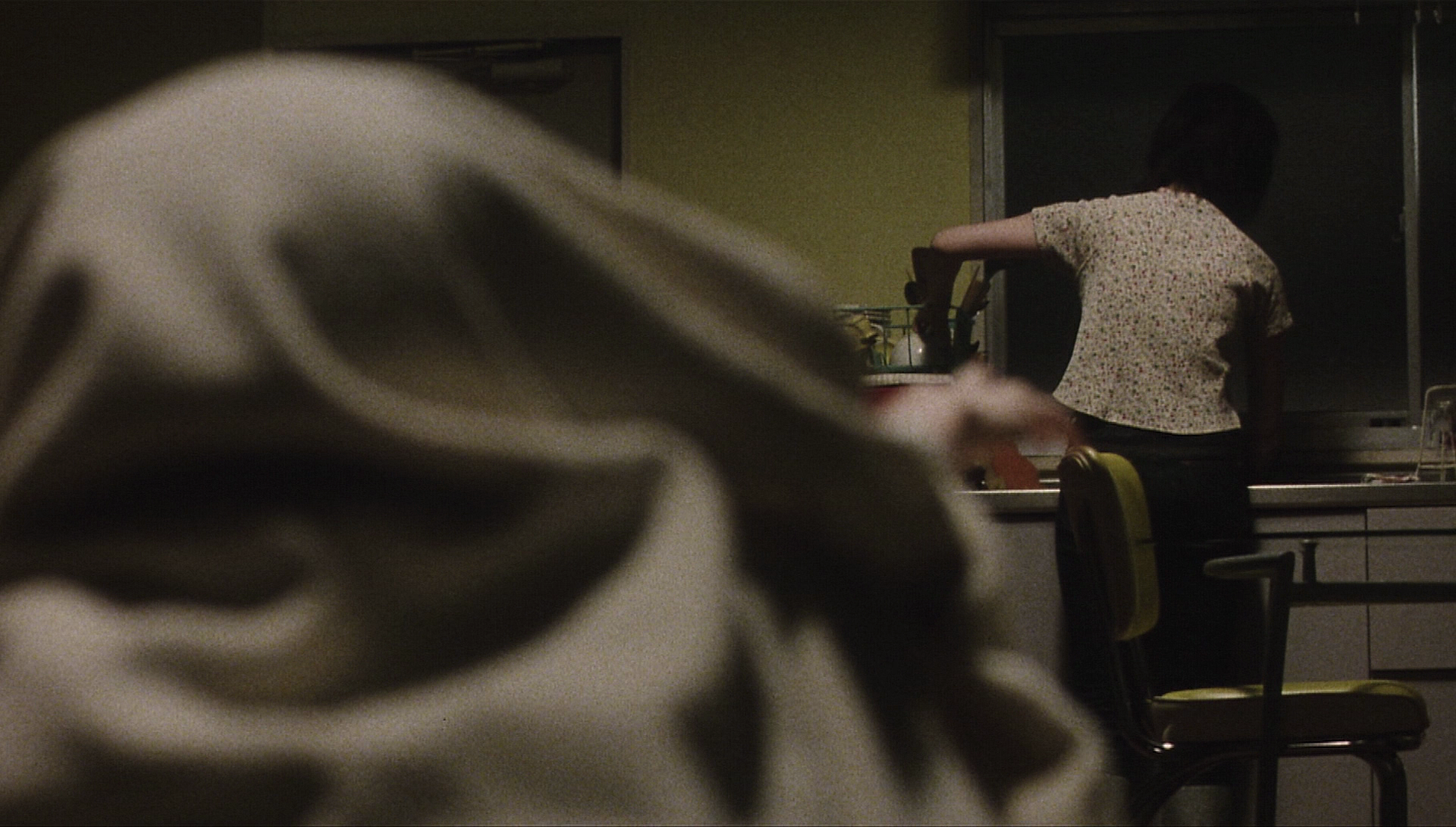

Adam Bingham suggests that ‘the vision here is of a fundamental powerlessness, a helplessness in the face of something amorphous that can barely be defined, much less comprehended’ (Bingham, 2015: 86). Unlike many other J-horror films, in Pulse ‘there is no mystery to be solved or overtly evil force to be repelled or expelled’ (ibid.). Similarly, the ghosts in Pulse have nothing ‘inherently evil’ within them: ‘[t]hey are not the malign, vengeful entities that Nakata and Shimizu envision, and it is notable that their “victims” may well be seen to bring about their own deaths. They all commit suicide rather than actually being killed by the ghosts’ (ibid.: 88). Bingham suggests that Pulse may be compared with films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1962) and Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (1979), ‘in which the horror becomes a manifestation of the precariousness of human existence, of the potential chaos underlying the fragile and tenuous order with which humanity lives and against which it must struggle to define itself’ (ibid: 86). The young protagonists of the film ‘lead isolated and insular lives; they all live alone, interact at work or university on a largely prescriptive and professional rather than a personal basis, and the perennial presence of mobile phones and the Internet exacerbates personal alienation and disconnection’ (ibid.). Bingham suggests that the proliferation of mediated images within the film (eg, video footage and photographs on the characters’ computers and mobile telephones) and the use of frames-within-the frame in the compositions speak ‘of the potential threat of imagery, of becoming an image in the sense of being removed and distinct from other people’ (ibid.: 87).  As in his other films, Kurosawa makes excellent use of space in this picture, aided by Hayashi Junichiro’s photographer (Hayashi was also the director of photography for Nakata’s The Ring). For most of the film’s running time, Pulse’s characters are placed in cramped, confined spaces: their homes are small and crowded. Rather than shooting these cramped interiors with wide angle lenses, Hayashi uses focal lengths that compress space somewhat, making even the rooms in the university seem cramped and crowded by objects. These rooms are filled with negative space in which the potential for something frightening to appear escalates: characters enter empty rooms, only for a ‘ghost’ to appear out of the seemingly empty shadows. When Michi explores Taguchi’s flat, at first it seems to be empty; we only become aware that someone other than Michi is present when we see a figure silhouetted against a window behind her and separated from her by a plastic sheet. Michi moves the plastic sheet aside and discovers Taguchi. They converse briefly, and Michi leaves him alone, only to hear a thudding noise which she discovers, on investigating it, to be the sound made by Taguchi’s hanged corpse as it gently bumps against the wall. Later, when Yabe visits the Forbidden Room, he finds it to be empty. He enters the room, only to discover upon turning around that a ‘ghost’ appears out of the empty shadows behind the door through which he entered the room, thus blocking his escape. Empty space itself becomes threatening, loaded with the potential for supernatural phenomena to ooze or crawl out of it. When we do see the characters outside these cramped interior spaces, it is invariably at night time. In one of the film’s few scenes that takes place outside and in the daytime, Michi ventures outside only to witness a woman commit suicide by leaping from a water tower. Michi is framed with the woman in the background; our eye is drawn from Michi’s face to the woman climbing to the top of the water tower before jumping from it. As the narrative progresses, Michi and Kawashima find themselves in spaces which should be filled with people but are instead deserted: whilst caring for Junko, Michi makes an excursion to a supermarket and browses through its aisles before realising that the place is empty – not only are there no customers, but there are also no members of staff; shortly after, Kawashima is shown in an empty arcade, again strangely empty of customers and employees. Towards the end of the film, Kawashima and Michi finally find themselves on the city streets during the day, but find that the city is now an apocalyptic landscape. The population has vanished, leaving behind only crashed, burning cars and aeroplanes that fall from the sky. As in his other films, Kurosawa makes excellent use of space in this picture, aided by Hayashi Junichiro’s photographer (Hayashi was also the director of photography for Nakata’s The Ring). For most of the film’s running time, Pulse’s characters are placed in cramped, confined spaces: their homes are small and crowded. Rather than shooting these cramped interiors with wide angle lenses, Hayashi uses focal lengths that compress space somewhat, making even the rooms in the university seem cramped and crowded by objects. These rooms are filled with negative space in which the potential for something frightening to appear escalates: characters enter empty rooms, only for a ‘ghost’ to appear out of the seemingly empty shadows. When Michi explores Taguchi’s flat, at first it seems to be empty; we only become aware that someone other than Michi is present when we see a figure silhouetted against a window behind her and separated from her by a plastic sheet. Michi moves the plastic sheet aside and discovers Taguchi. They converse briefly, and Michi leaves him alone, only to hear a thudding noise which she discovers, on investigating it, to be the sound made by Taguchi’s hanged corpse as it gently bumps against the wall. Later, when Yabe visits the Forbidden Room, he finds it to be empty. He enters the room, only to discover upon turning around that a ‘ghost’ appears out of the empty shadows behind the door through which he entered the room, thus blocking his escape. Empty space itself becomes threatening, loaded with the potential for supernatural phenomena to ooze or crawl out of it. When we do see the characters outside these cramped interior spaces, it is invariably at night time. In one of the film’s few scenes that takes place outside and in the daytime, Michi ventures outside only to witness a woman commit suicide by leaping from a water tower. Michi is framed with the woman in the background; our eye is drawn from Michi’s face to the woman climbing to the top of the water tower before jumping from it. As the narrative progresses, Michi and Kawashima find themselves in spaces which should be filled with people but are instead deserted: whilst caring for Junko, Michi makes an excursion to a supermarket and browses through its aisles before realising that the place is empty – not only are there no customers, but there are also no members of staff; shortly after, Kawashima is shown in an empty arcade, again strangely empty of customers and employees. Towards the end of the film, Kawashima and Michi finally find themselves on the city streets during the day, but find that the city is now an apocalyptic landscape. The population has vanished, leaving behind only crashed, burning cars and aeroplanes that fall from the sky.

Video

Pulse takes up a little over 32Gb on its dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. The film is uncut, running for 118:57 mins. Pulse takes up a little over 32Gb on its dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. The film is uncut, running for 118:57 mins.

Sadly, the presentation is quite disappointing. The HD master was provided to Arrow by Kadokawa Pictures. This seems to be an older master, presumably created in the pre-Blu-ray era, with similar qualities to the presentation found on the Hong Kong DVD release from Universe (rather than the brighter presentation released on DVD in some other territories). The film has always had a presumably intentional murky appearance, the palette dominated by browns, greens and whites; but this new presentation has whites that seem ‘off’ and contains a sickly hue throughout. The image lacks definition, with a level of detail that is perhaps a smidgen above that present in the Hong Kong DVD release (the only DVD release of this film I’ve previously owned) but otherwise this new presentation is very similar to that release. Contrast is iffy: shadows are soft and ‘crushed’ whilst highlights bloom. The midtones lack texture and gradation at times too. In fact, though the film was shot on 35mm film, this presentation has the characteristics of early 2000s digital video – complete with its flattened dynamic range. Grain is present but sometimes looks a little like video noise as much as 35mm grain. Pulse has always been a murky-looking film, but even taking that into account the master Arrow have been given to work with looks very weak, lacking definition and containing poor contrast.

Audio

Audio is more impressive. The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 track (in Japanese, naturally). Sound separation is impressive, the eerie music shining through, and the whispered voices of the dead are incredibly unsettling on this track. The film is accompanied by optional English subtitles, which are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Kiyoshi Kurosawa: Broken Circuits’ (43:53). In a new interview, Kurosawa reflects on his career. He talks about how he started making films as a student and discusses his work in V-Cinema before transitioning to theatrical features. Kurosawa’s comments are bolstered by clips from the films and comments from Aikawa Show, with whom Kurosawa has made ten features. Kurosawa reflects on the importance of Cure in his career and discusses the significance of Nakata’s Ring in helping shape the direction of Pulse. He admits that he didn’t think the ‘Japanese horror craze’ would last very long, and discusses some of the ways in which American horror films have been shaped by J-horror films but adopt an ‘explosive style that is very American’ in the stead of the more sedate approach of the Japanese horror films. The interview is in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - ‘Junichiro Hiyashi: Creepy Images’ (25:03). In another new interview, cinematographer Hiyashi discusses the film’s photography. Hiyashi suggests that in a horror film, sound and image need to work in harmony. He discusses some of the difficulties in working with directors, offering some highly amusing anecdotes about this. He and Kurosawak discuss their attempts to make the audience anxious by using light and shadow. Hiyashi speaks in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘The Horror of Isolation’ (17:11). Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett, the writer and director of the new Blair Witch film (2016) discuss the influence Pulse and other J-horror films have had on their work. - Archival Making of Featurette (41:03). This compilation of behind-the-scenes clips and interviews with the personnel is presented with burnt-in English subtitles. - Tokyo Premiere Introduction (7:04). Kurosawa and his cast introduce the film to the audience at the 2001 premiere of Pulse. Optional English subtitles are provided. - Cannes Film Festival (2:57). Shot at Cannes in 2001, this footage features Kurosawa and Kato Haruhiko talking about the film with journalists and introducing a screening of the picture. - Special Effects Breakdowns. These short pieces explain how some of the film’s effects were achieved. -- The Suicide Jump (6:22). -- Harue's Death Scene (5:02). -- Junko's Death Scene (4:31). -- Dark Room Scenes (10:18). - TV Spots (4:15). - NHK Station IDs (0:15). Retail copies include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet.

Overall

Pulse is an interesting, unsettling film, arguably one of the best pictures to come out of the J-horror boom of the early 2000s. Kurosawa takes a minimalistic approach, the actors giving muted performances that suggest the characters are sleepwalking – a little like the strange, trance-like performances in Werner Herzog’s Herz aus Glas (Heart of Glass, 1976). The scenes in which the ghosts appear are genuinely frightening, Kurosawa making excellent use of empty/negative space and shadow. I’ve suffered from intermittent stress-triggered sleep paralysis for all of my adult life, and when I first saw Pulse in 2001/2 I remember commenting to the friend I saw it with that the scene in which Yabe enters The Forbidden Room and encounters the ghost that creeps out of the shadows and slowly approaches him (whilst he is paralysed with fear) is perhaps one of the closest sequences in cinema to capture the terrifying potential of that unpleasant condition. The film’s first half hour is the most tense, but the apocalyptic final sequences resonate too. Pulse is an interesting, unsettling film, arguably one of the best pictures to come out of the J-horror boom of the early 2000s. Kurosawa takes a minimalistic approach, the actors giving muted performances that suggest the characters are sleepwalking – a little like the strange, trance-like performances in Werner Herzog’s Herz aus Glas (Heart of Glass, 1976). The scenes in which the ghosts appear are genuinely frightening, Kurosawa making excellent use of empty/negative space and shadow. I’ve suffered from intermittent stress-triggered sleep paralysis for all of my adult life, and when I first saw Pulse in 2001/2 I remember commenting to the friend I saw it with that the scene in which Yabe enters The Forbidden Room and encounters the ghost that creeps out of the shadows and slowly approaches him (whilst he is paralysed with fear) is perhaps one of the closest sequences in cinema to capture the terrifying potential of that unpleasant condition. The film’s first half hour is the most tense, but the apocalyptic final sequences resonate too.

This new Blu-ray release from Arrow contains a disappointing presentation of the main feature, which seems to be a result of the limited qualities of the master provided to Arrow by Kadokawa Pictures. Nevertheless, disappointment in the main presentation is mitigated somewhat by the superb contextual material included on this release. The interviews that have been gathered for inclusion here are excellent. Even though Arrow seem to have been provided with an older, problematic master, it’s great to see this excellent film hit the Blu-ray format – especially given the qualities of the extra features included on this disc. References: Bingham, Adam, 2015: Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since ‘Hana-Bi’. Edinburgh University Press Kinoshita, Chika, 2010: ‘The Mummy Complex: Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Loft and J-horror’. In: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo (eds), 2010: Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press: 103-22 Walter, Brenda S Gardenour, 2014: ‘Ghastly Transmissions: The Horror of Connectivity and the Transnational Flow of Fear’. In: Och, Diana & Strayer, Kristen (eds), 2014: Transnational Horror Across Visual Media: Fragmented Bodies. London: Routledge: np Wee, Valerie, 2014: Japanese Horror Films and Their American Remakes. London: Routledge

|

|||||

|