|

The Film

The Ghoul (Gareth Tunley, 2016) The Ghoul (Gareth Tunley, 2016)

Police detective Chris (Tom Meeten) arrives in London. He meets with a colleague, Jim (Dan Renton Skinner). They enter a house where a shooting has taken place – only this one is, in Jim’s words, ‘a fucking doozy’: a man and a woman were apparently shot multiple times but neither of them died.

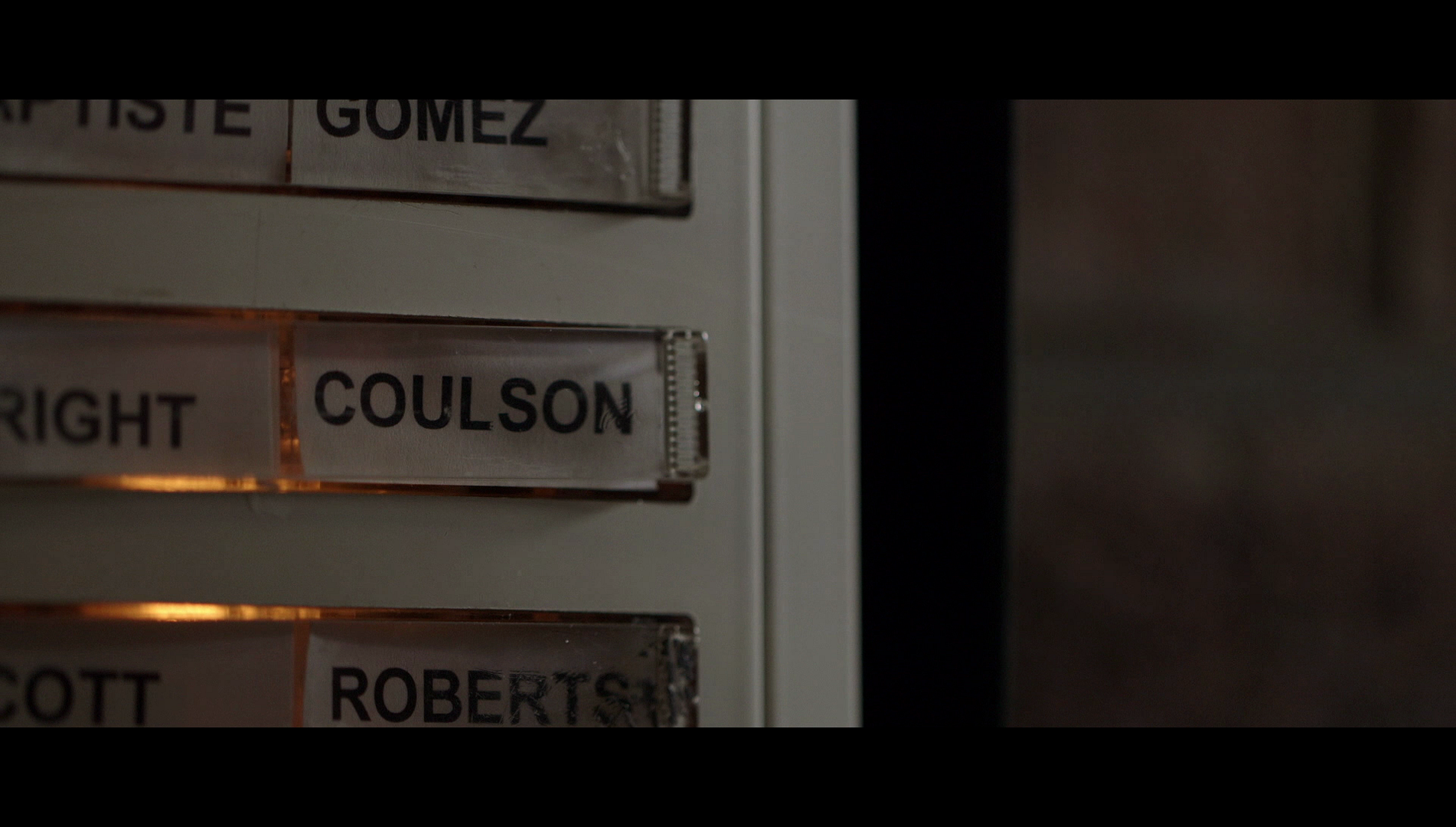

After mulling over the crime scene, Chris decides the best course of action is to investigate the property manager responsible for the house; the property manager is a man named Coulson (Rufus Jones), who has a reputation for ‘hang[ing] around criminals and crime scenes’. Coulson is under therapy for what he claims is manic depression, though Kath (Alice Lowe), a psychologist and friend of Chris, suggests that Coulson may be faking these symptoms because ‘he’s a ghoul’.

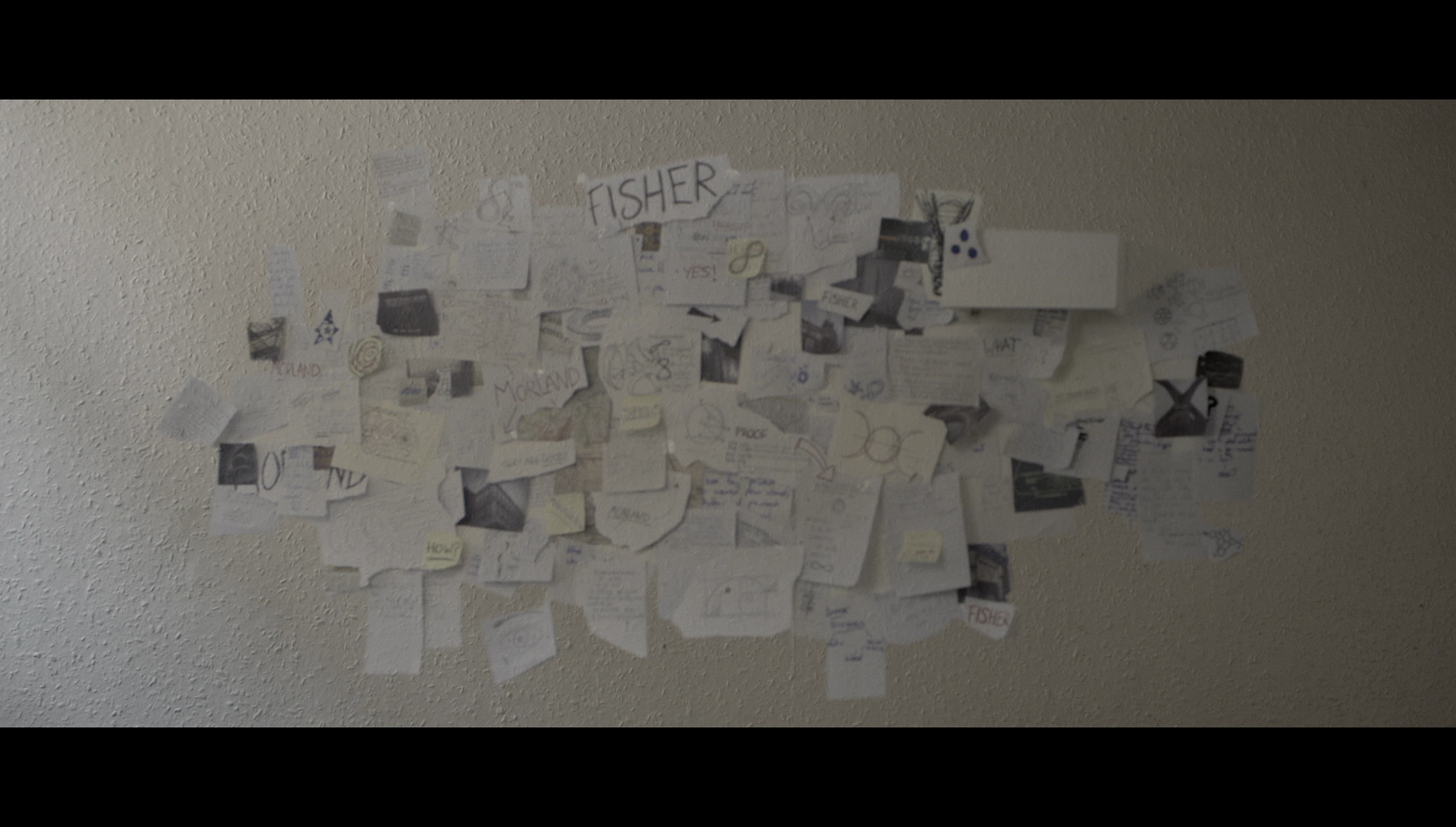

Deciding to go undercover as a prospective patient of Coulson’s psychotherapist, Fisher (Niamh Cusack), Chris asks Kath to advise him on a specific type of depression, dysthymia, so that he may fake the symptoms. Chris attends a series of sessions with Fisher, living in a bedsit. However, soon he becomes uncertain as to which is his ‘real’ life: the unemployed depressive he claims to be, or the undercover detective that he tells Fisher is his fantasy. In the former, Kath is a psychological profiler working with the police; in the latter, she is a schoolteacher who is involved in an unhappy marriage with Jim, who instead of being a police detective ‘works for a drinks company’.

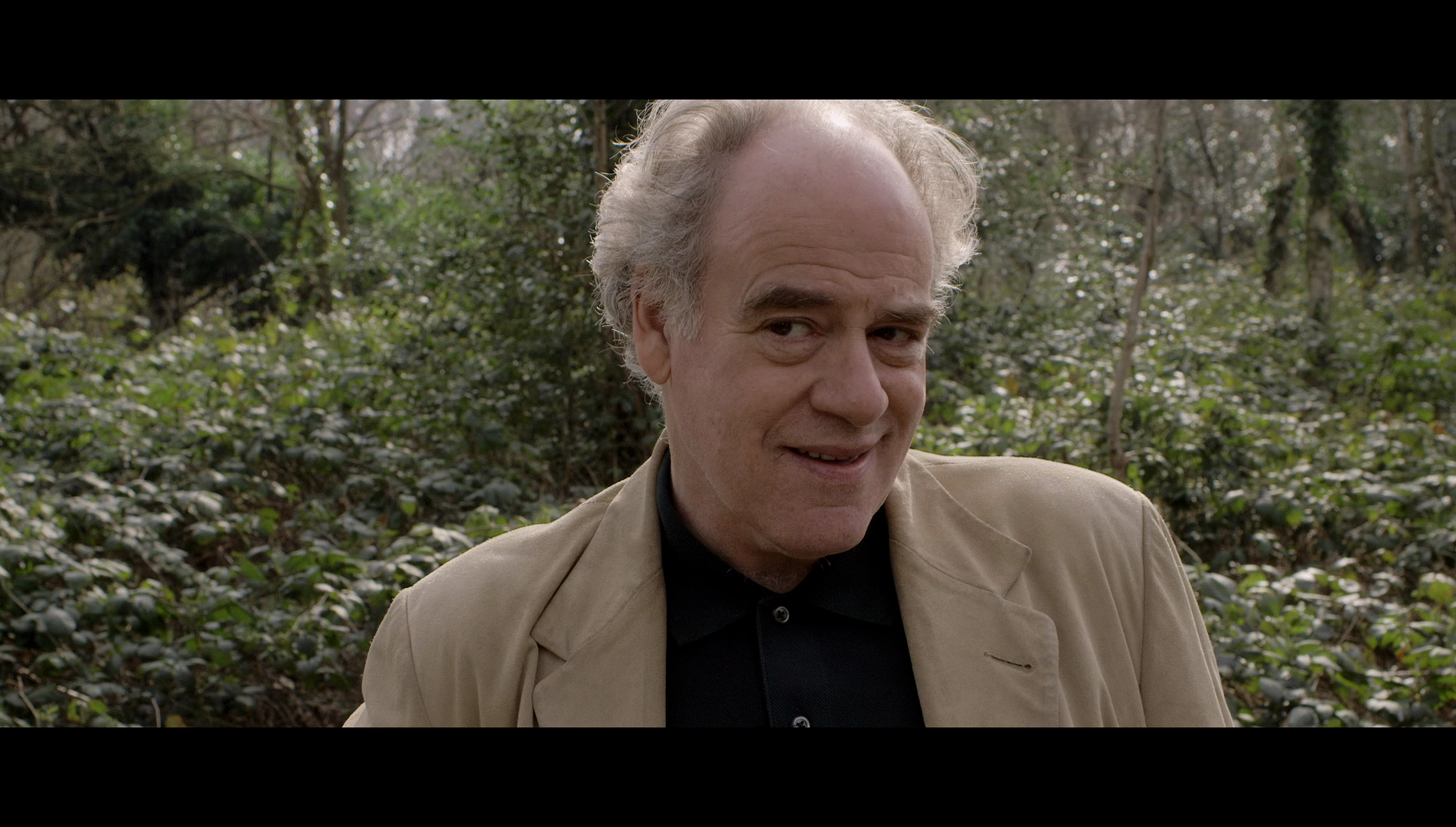

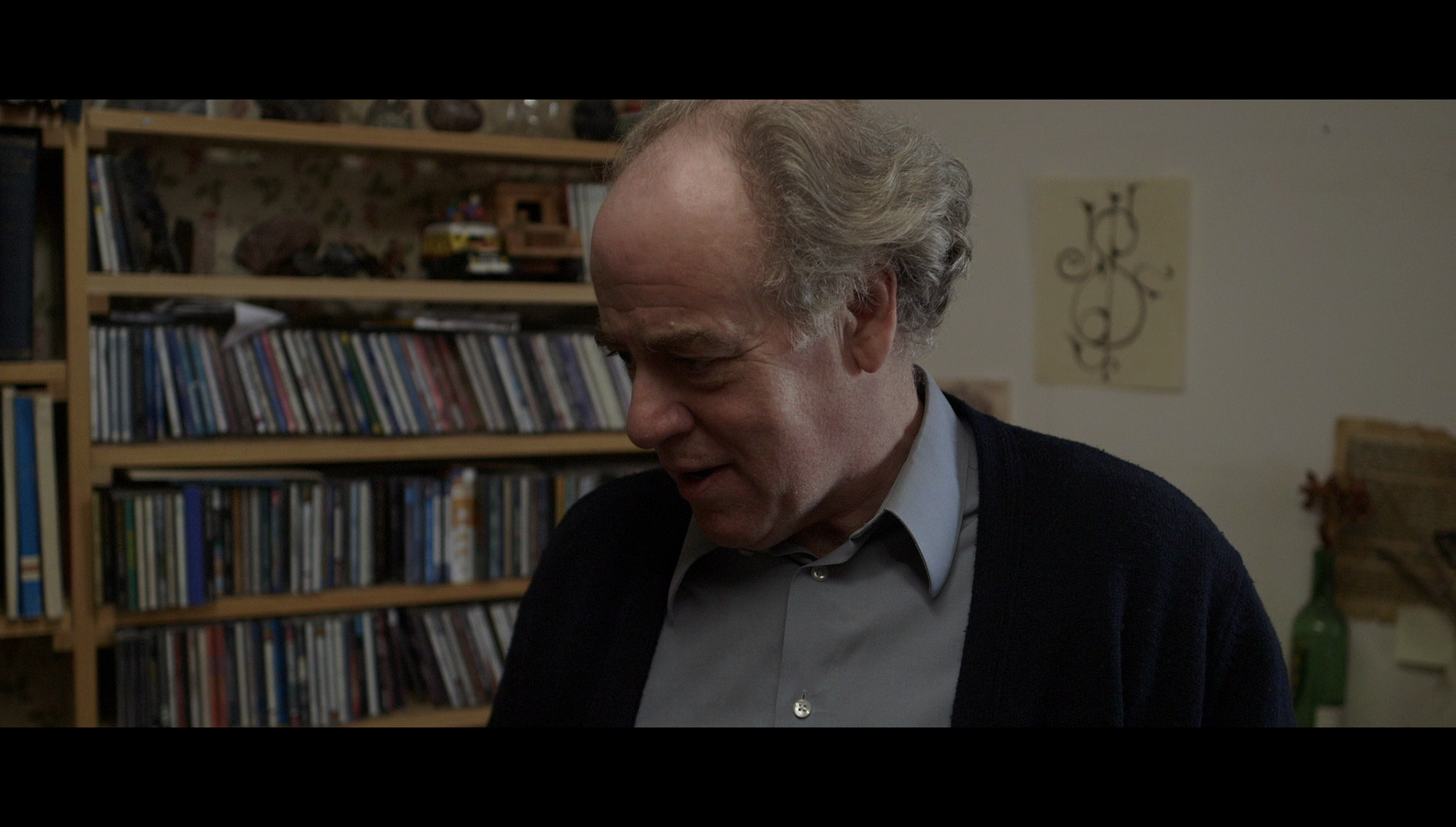

Chris makes contact with Coulson, and the two become friendly. Claiming that she is in the grip of an illness, Fisher recommends both Coulson and Chris to her mentor, Alexander Morland (Geoffrey McGivern). Morland is fascinated with the arcane: Coulson notes to Chris that Morland ‘is into some weird shit. Magic, the occult, weird science’. During one of Chris’ therapy sessions, Morland shows him a Klein bottle, telling him that ‘It’s got no inside or outside’; from there, Morland launches into a discussion of the Möbius strip and the ourobouros, ‘the eternal return and all that’. Morland encourages Chris to ‘name’ his depression, in a moment that suggests ritualistic conjuration; Chris names his depression ‘The Ghoul’. Chris makes contact with Coulson, and the two become friendly. Claiming that she is in the grip of an illness, Fisher recommends both Coulson and Chris to her mentor, Alexander Morland (Geoffrey McGivern). Morland is fascinated with the arcane: Coulson notes to Chris that Morland ‘is into some weird shit. Magic, the occult, weird science’. During one of Chris’ therapy sessions, Morland shows him a Klein bottle, telling him that ‘It’s got no inside or outside’; from there, Morland launches into a discussion of the Möbius strip and the ourobouros, ‘the eternal return and all that’. Morland encourages Chris to ‘name’ his depression, in a moment that suggests ritualistic conjuration; Chris names his depression ‘The Ghoul’.

After disappearing for a while, Coulson makes contact with Chris and warns him of Morland and Fisher. Coulson suggests that Morland and Fisher ‘believe they can create a loop inside a person’s mind’ and that Morland is ‘a sorcerer’ intent on ‘creating a universe of the mind’ in which he and Fisher may live forever. Meanwhile, Morland warns Chris to stay away from Coulson, claiming that Coulson is ‘very adept at putting ideas in people’s heads’. A confused Chris must attempt to identify who he is and which of his identities is the ‘true’ one.

Produced by Ben Wheatley and written and directed by Gareth Tunley, who previously collaborated as an actor with Wheatley on Wheatley’s films Down Terrace (2009), Kill List (2011) and Sightseers (2012), The Ghoul is a strange picture that, though it shares its title with the well-regarded 1933 Boris Karloff picture (not to mention Freddie Francis’ 1975 Peter Cushing and John Hurt-starring terror film), defies easy classification as a ‘horror’ film.

The film was edited by Robin Hill, who also edited Ben Wheatley’s pictures Down Terrace (2009), Kill List (2011) and Sightseers (2012), and The Ghoul makes some effective use of dreamy non-linear montage, the narrative offering glimpses of the past in a similar manner to Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey (1999), for example. The Ghoul also features a number of familiar faces in front of the camera, including Sightseers’ Tom Meeten and Alice Lowe. Paul Kaye arguably steals the show as a partygoer who regales Chris and Coulson with a story about how he staved off certain death at the hands of a group of irate criminals by praying to ‘any cunt who would fucking listen’. ‘What if you really are an undercover cop?’, Kaye’s character asks Chris, ‘and you’re just imagining you’re a normal person’ – they (Fisher and Morland) ‘flipped you’.

The fluidity that exists within Chris’ two existences, and the question that arises as to which of them is ‘real’ (is he really an undercover policeman, or is he a jobless depressive fantasising that he’s an undercover policeman?), is handled in a manner that might invite comparisons with David Lynch. In particular, watching The Ghoul for the first time feels very much like the experience of seeing Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) on its initial release – minus the Rammstein tracks, of course. Once Chris comes into contact with Fisher, he begins to rapidly lose any sense of who he is – and the film’s viewer is encouraged to empathise with him. It is unclear to Chris (and to us) which is the ‘real’ Chris: the depressed man undergoing therapy with Fisher, or the detective who is undercover as one of Fisher’s patients. ‘Why would someone pretend to have an illness they don’t have?’, Chris asks Kath when they discover that Coulson is apparently faking the symptoms of manic depression. ‘Pot and kettle’, Kath responds pithily. To Fisher, Chris declares that ‘Sometimes I daydream that I’m undercover in real life. When I’m here, I pretend that I’m undercover and it’s part of an investigation’. The fluidity that exists within Chris’ two existences, and the question that arises as to which of them is ‘real’ (is he really an undercover policeman, or is he a jobless depressive fantasising that he’s an undercover policeman?), is handled in a manner that might invite comparisons with David Lynch. In particular, watching The Ghoul for the first time feels very much like the experience of seeing Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) on its initial release – minus the Rammstein tracks, of course. Once Chris comes into contact with Fisher, he begins to rapidly lose any sense of who he is – and the film’s viewer is encouraged to empathise with him. It is unclear to Chris (and to us) which is the ‘real’ Chris: the depressed man undergoing therapy with Fisher, or the detective who is undercover as one of Fisher’s patients. ‘Why would someone pretend to have an illness they don’t have?’, Chris asks Kath when they discover that Coulson is apparently faking the symptoms of manic depression. ‘Pot and kettle’, Kath responds pithily. To Fisher, Chris declares that ‘Sometimes I daydream that I’m undercover in real life. When I’m here, I pretend that I’m undercover and it’s part of an investigation’.

The film makes much play on the distinction between the North and the South, which become highly charged symbolic spaces. In the film’s opening sequence, from the point-of-view of Chris’ car, we see the approach into the South and London via the M1 motorway. Chris’ movement is the opposite of that of Jack Carter in Mike Hodges’ Get Carter (1971), but the connotations of the North and South have some similarities with that iconic 1970s film. Though not depicted explicitly within the film, the North is framed as an imaginary, idealised space that is connected to youth and past moments of happiness; the South, on the other hand, is a depressing zone of bedsits, murders and unhappy relationships. When Chris first visits Kath, she asks him ‘Where have you been?’ ‘Up north’, he tells her. ‘Man of fucking mystery, aren’t you?’, she jokes before, shortly afterwards, telling him, ‘You should have stayed up north, Chris’. Following his therapy sessions with Fisher, Chris reflects on his relationship with Kath; Chris tells Fisher that he, Kath and Jim met at university in Manchester, where Chris fell in love with Kath. However, Kath eventually married Jim. After Morland tells Chris about sigils, Chris devises his own sigil (based on the phrase ‘Bring Kath to me’) and discovers that it works: Kath comes to Chris, confiding in him her doubts about her relationship with Jim. However, later in the film Chris is dismayed to discover that Kath and Jim are planning to move back to the North together, in an attempt to rekindle their relationship.

Throughout, there’s a strong suggestion that Chris’ existence is purgatorial, in both a literal and figurative sense: ‘Yeah, we’re all in hell’, Coulson tells Chris not long after they meet for the first time, ‘Some of us just don’t remember why we were put there’. Chris’ repetition of this line during one of his meetings with Morland provokes consternation in the psychotherapist, who tells Chris that it’s dangerous to be around Coulson – that Chris’ association with Coulson will impact on Chris’ sense of reality. For his part, Morland is clearly an Aleister Crowley-type figure, and to some extent invites comparison with Karswell in M R James’ short story ‘Casting the Runes’ (and, by extension, Niall McGinnis’ performance as Karswell in Jacques Tourneur’s 1957 adaptation of James’ story, Curse of the Demon). Morland admits that his approach is mystical: ‘This is what we’re doing’, he tells Chris, ‘trying to make you better; that’s alchemy’. Throughout, there’s a strong suggestion that Chris’ existence is purgatorial, in both a literal and figurative sense: ‘Yeah, we’re all in hell’, Coulson tells Chris not long after they meet for the first time, ‘Some of us just don’t remember why we were put there’. Chris’ repetition of this line during one of his meetings with Morland provokes consternation in the psychotherapist, who tells Chris that it’s dangerous to be around Coulson – that Chris’ association with Coulson will impact on Chris’ sense of reality. For his part, Morland is clearly an Aleister Crowley-type figure, and to some extent invites comparison with Karswell in M R James’ short story ‘Casting the Runes’ (and, by extension, Niall McGinnis’ performance as Karswell in Jacques Tourneur’s 1957 adaptation of James’ story, Curse of the Demon). Morland admits that his approach is mystical: ‘This is what we’re doing’, he tells Chris, ‘trying to make you better; that’s alchemy’.

Video

The film takes up a little over 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is uncut, running for 95:09 mins. The film takes up a little over 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is uncut, running for 95:09 mins.

The Ghoul was shot digitally, and the photography is interesting. Exposures are frequently balanced low, characters framed in half-silhouette. The widescreen frame is often partially obscured by objects in the foreground: shallow depth of field is frequently utilised along with the placing of objects near to the camera to obscure, partially, the primary focal point. This results in a very enigmatic style of photography that suits the mysterious narrative of the film.

The digital photography is captured very nicely in this HD presentation, a very good level of detail on display, especially in close-ups of the actors’ faces. Contrast levels are balanced nicely, with defined midtones. Colour is handled naturalistically throughout the production, and this is communicated well in this Blu-ray presentation too.

This is a compressed digital clone of a digitally shot feature, and as such the most significant element is perhaps the encode to disc. This is fine and without issues, no digital artifacts or anything of that sort being present throughout the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. This is rich and deep, dialogue always clear. It’s not a ‘showy’ track, but the sound separation is immersive when it needs to be. The optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are clear and easy to read, transcribing the dialogue accurately.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with writer-director Gareth Tunley, Tom Meeten and producer Jack Guttman. With a wealth of good humour, the trio discuss the origins of the film and talk about some of the techniques employed in the production and editing of the picture. It’s a fun and informative track that is well worth a listen.

- ‘In the Loop’ (36:17). A documentary focusing on the inception and production of The Ghoul, this includes interviews with Tunley, Tom Meeten, Alice Lowe, Geoff McGivern, Niamh Cusack, Rufus Jones, Dan Skinner, cinematographer Ben Pritchard, producer Jack Guttman, composer Waen Shepherd, and executive producers Ben Wheatley and Dhiraj Mahey.

- ‘The Baron’ (9:27). Directed by Gareth Tunley, this short film was written by Tunley and Tom Meeten, who also stars alongside Steve Oram, Barunka O’Shaughnessey and Steve Evans. The short film is viewable with an optional commentary by Tunley and Meeten, in which they discuss the genesis of the short.

- Trailer (1:34).

Overall

To some extent, in its depiction of Chris’ confusion as to which is his ‘real’ life and which is his ‘fantasy’, The Ghoul is highly reminiscent of Sam Fuller’s incredible film Shock Corridor (1960), in which a newspaper reporter goes undercover in an insane asylum only for his undercover identity to take over – resulting in the reporter becoming, by the end of the picture, a schizophrenic catatonic. The Ghoul is careful to make references to the occult that are grounded in much more careful research than the majority of modern horror pictures – Morland’s explanation of sigils, for example, or the inclusion within the mise-en-scène of various objets d’art, including portraits of the likes of John Dee. The film manages to give its London setting, and its brief journeys into woodlands, etc, a strong symbolic charge; the mundane becomes threatening. The tension between the ‘real’ and the ‘imaginary’, and the ‘past’ and the ‘present’, becomes wrapped up in a symbolic juxtaposition of the North and the South. It’s an interesting film, though no doubt some viewers will find it immensely frustrating. Taken as a whole, the narrative has the texture of a modern-day take on M R James' themes, in particular. To some extent, in its depiction of Chris’ confusion as to which is his ‘real’ life and which is his ‘fantasy’, The Ghoul is highly reminiscent of Sam Fuller’s incredible film Shock Corridor (1960), in which a newspaper reporter goes undercover in an insane asylum only for his undercover identity to take over – resulting in the reporter becoming, by the end of the picture, a schizophrenic catatonic. The Ghoul is careful to make references to the occult that are grounded in much more careful research than the majority of modern horror pictures – Morland’s explanation of sigils, for example, or the inclusion within the mise-en-scène of various objets d’art, including portraits of the likes of John Dee. The film manages to give its London setting, and its brief journeys into woodlands, etc, a strong symbolic charge; the mundane becomes threatening. The tension between the ‘real’ and the ‘imaginary’, and the ‘past’ and the ‘present’, becomes wrapped up in a symbolic juxtaposition of the North and the South. It’s an interesting film, though no doubt some viewers will find it immensely frustrating. Taken as a whole, the narrative has the texture of a modern-day take on M R James' themes, in particular.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of the film is excellent. The digitally shot feature is represented very well in this HD presentation, and the picture is accompanied by some good contextual material.

|