|

|

The Film

La leggenda del santo bevitore AKA The Legend of the Holy Drinker (Ermanno Olmi, 1988) La leggenda del santo bevitore AKA The Legend of the Holy Drinker (Ermanno Olmi, 1988)

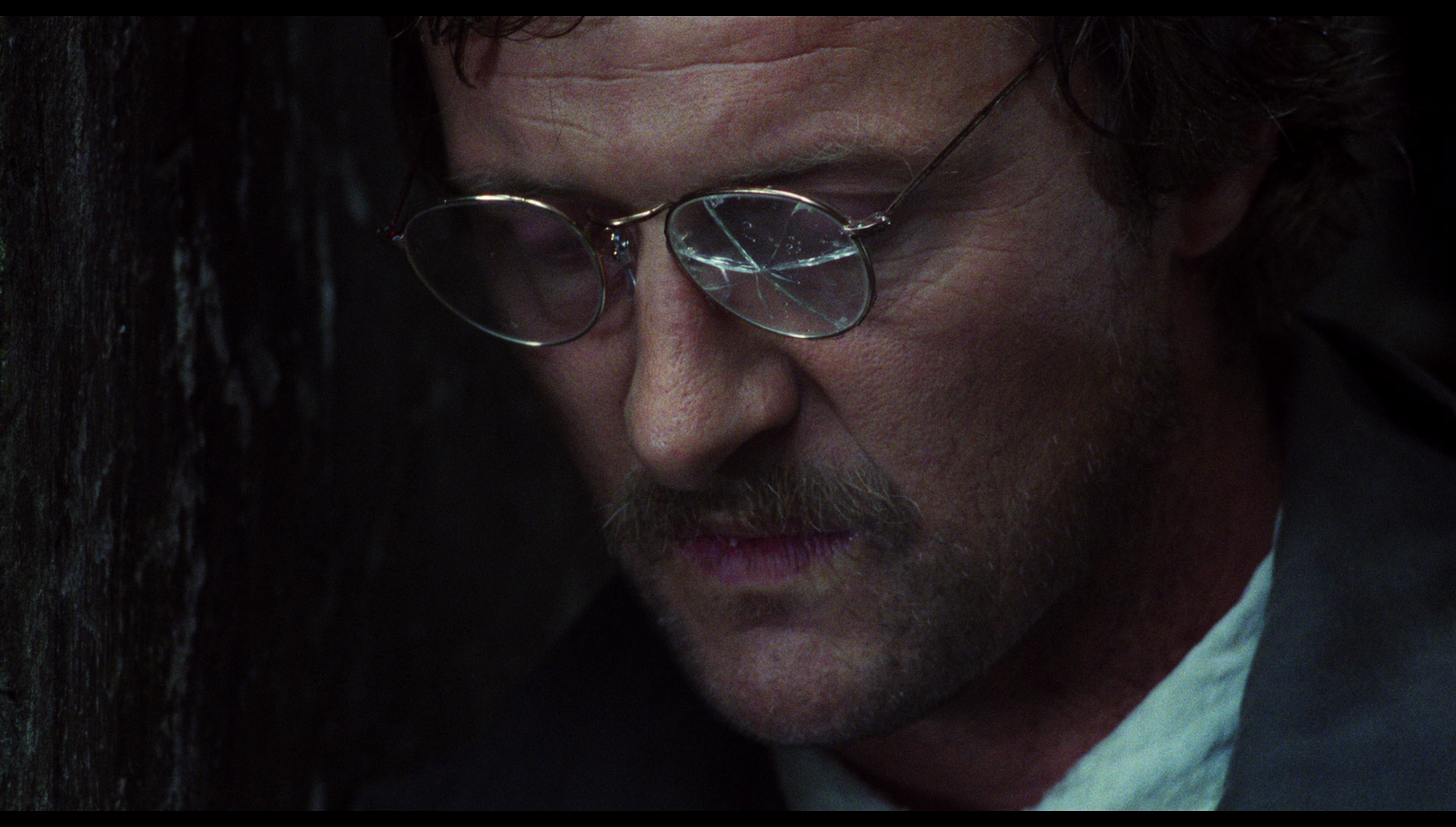

Austrian writer Joseph Roth’s 1939 novella The Legend of the Holy Drinker was published posthumously, following Roth’s death at the age of 44. The novella was partly autobiographical: like the protagonist of the story, Andreas, Roth was an alcoholic who lived an almost transient lifestyle, drifting between hotels. In The Legend of the Holy Drinker, Andreas struggles to resist the negative stereotypes associated with his status in life and prove himself to be a gentleman of honour; it’s difficult not to see in Andreas a reflection of Roth himself, a man struggling with his addiction to alcohol and striving to assert himself as a man worthy of trust and redemption. The story has similarities with other examples of literature focusing on down-and-outs, including Charles Bukowski’s novels Post Office (1971), Women (1978) and Factotum (1975) (all also partly autobiographical) and George Orwell’s memoir Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). Andreas (Rutger Hauer), an alcoholic down-and-out who, like many others in his situation, has taken to sleeping under the bridges that cross the Seine, encounters an elderly, wealthy Christian (Anthony Quayle). The Christian claims to have had an epiphany whilst visiting the statue of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux at a small church in Sainte-Marie de Batignolle; recognising Andreas’ poverty, the Christian offers Andreas 200 francs – but only if Andreas agrees to repay the debt, when he can afford to, by visiting the church and giving the money to the priest after Sunday Mass. Andreas agrees.  With the 200 francs, Andreas lives the life of a bourgeois – buying a newspaper, a new coat, a morning coffee in a café, and a shave and haircut at a barber’s. At a café during lunch, Andreas meets a tailor (Joseph De Medina) who offers him a job for a couple of days: the job will require Andreas to help the tailor pack and move his belongings. The fee is 200 francs, enough to allow Andreas to repay his debt to the Christian. Prior to commencing his labours, Andreas visits a shop and buys a wallet from a beautiful woman; his interest in the opposite sex reaffirmed, Andreas relocates to a brothel. With the 200 francs, Andreas lives the life of a bourgeois – buying a newspaper, a new coat, a morning coffee in a café, and a shave and haircut at a barber’s. At a café during lunch, Andreas meets a tailor (Joseph De Medina) who offers him a job for a couple of days: the job will require Andreas to help the tailor pack and move his belongings. The fee is 200 francs, enough to allow Andreas to repay his debt to the Christian. Prior to commencing his labours, Andreas visits a shop and buys a wallet from a beautiful woman; his interest in the opposite sex reaffirmed, Andreas relocates to a brothel.

The next day, Andreas arrives at the tailor’s appartement; after his day at work, he visits the pub and drinks. The next day, Andreas returns and completes his task. On Saturday evening, he relocates to a hotel near the church and takes a room there. He is awoken by the church bells ringing. On his way to the church, however, he is surprised to encounter his former lover, Karoline (Sophie Segalen). Karoline ushers Andreas away from the church before he can complete his task. They go dancing and then spend the night together in the hotel. His quest frustrated by his encounter with his former lover, Andreas returns to the bridge under the Seine which he has made his home. He falls asleep under a pile of newspapers but is awoken by a young girl. ‘Why didn’t you come to see me last Sunday?’, she asks: it is Saint Thérèse. The young girl departs. Miraculously, Andreas finds a wallet with yet another 200 francs in it. Visiting a pub, he sees a photograph of a boxer, Daniel Kanjak (Jean-Maurice Chanet); recognising Kanjak as an old schoolfriend, Andreas seeks him out. Kanjak is ecstatic to see Andreas, claiming he owes Andreas at least 1,000 francs owing to the fact that Andreas used to allow Kanjak to copy his schoolwork. Discovering Andreas is homeless, Kanjak puts Andreas up in a lush hotel room and takes him out for the evening.  At the hotel, Andreas enjoys simple luxuries – a bath and the company of a beautiful young dancer, Gaby (Sandrine Dumas). However, Gaby is astonished when Andreas leaps out of bed on Sunday morning and asserts that he has a debt to pay. ‘On Sunday?’, she queries, believing him to be rushing to a liaison with another woman. Near to the church, Andreas bumps into yet another old friend, Woitech (Dominique Pinon). Woitech sees the money in Andreas possession and lies to his friend, telling Andreas he is in debt and will be thrown in jail if he doesn’t give his debtors 200 francs. Selflessly, Andreas gives Woitech the money – thus preventing Andreas from fulfilling his debt to Saint Thérèse. Andreas and Woitech go drinking together, Andreas forgetting Gaby and talking about her as if his relationship with her was long in the past. At the hotel, Andreas enjoys simple luxuries – a bath and the company of a beautiful young dancer, Gaby (Sandrine Dumas). However, Gaby is astonished when Andreas leaps out of bed on Sunday morning and asserts that he has a debt to pay. ‘On Sunday?’, she queries, believing him to be rushing to a liaison with another woman. Near to the church, Andreas bumps into yet another old friend, Woitech (Dominique Pinon). Woitech sees the money in Andreas possession and lies to his friend, telling Andreas he is in debt and will be thrown in jail if he doesn’t give his debtors 200 francs. Selflessly, Andreas gives Woitech the money – thus preventing Andreas from fulfilling his debt to Saint Thérèse. Andreas and Woitech go drinking together, Andreas forgetting Gaby and talking about her as if his relationship with her was long in the past.

Near the bridge over the Seine, Andreas once again encounters the wealthy Christian. The man claims not to recognise Andreas but offers him another 200 francs all the same. The next Sunday, Andreas heads to the church again; again, he encounters Woitech. He also sees a young girl who he believes to be Saint Thérèse in the café, although the girl claims simply to be waiting for her parents – who are at Mass. Andreas apologises to the girl before being overcome with a malady and expiring. The film ends by quoting the final line of Roth’s novella, ‘May God grant us all, all of us drinkers, such a good and easy death’. A tale of down-and-outs, The Legend of the Holy Drinker sits amongst some interesting thematic companions which were made within the surrounding years, including Barbet Schroeder’s Charles Bukowski-inspired Barfly (1987) and Leos Carax’ Les amants du Pont-Neuf (1991). Olmi’s film adaptation of Roth’s novella was made after Olmi had spent a number of years away from filmmaking, an exile from the craft that had been forced upon him by ill health. Like Roth’s source novella, the texture of the film communicates the experience of alcoholism effortlessly: we are encouraged to feel Andreas’ blackouts, moments of confusion, forgetfulness and a hazy sense of time and place. ‘I was in love for two days’, Andreas tells Woitech in reference to Gaby, who he has left at the hotel that morning, as if his relationship with Gaby were a long time in the past.  Andreas’ encounter with the wealthy Christian gentleman on the steps near the bank of the Seine precipitates Andreas’ growing awareness of his status as a moral creature, this awareness allowing Andreas to slowly ease himself out of his state of permanent alcoholic ‘fuzz’. Precipitated by the Christian’s offer to ‘loan’ him 200 francs, Andreas becomes insistent in declaring that, despite his appearance, he is an honourable man. ‘I gave you my word’, Andreas tells the Christian, ‘I will keep my word’. (‘I must assure you I am still an honourable man’, Andreas tells the same man when he encounters him near the end of the picture.) Even after Andreas has acquired new clothes and bathed, throughout the picture his hands remain dirty: they become an index of his poverty. When he encounters the tailor who offers to pay Andreas to help move his belongings, Andreas declares that he is an honourable man despite his appearance – and holds up his dirty hands so that the tailor may see them. The tailor recognises the symbolism of this gesture and nods and smiles in acknowledgement of Andreas’ assertion that he is a man of honour and responsibility. Despite his repeated failure to pay his debt to Saint Thérèse, Andreas becomes increasingly convinced of divine providence – especially after he is ‘visited’ by Saint Thérèse as he sleeps under the bridge over the Seine, a visit during which she asks him why Andreas has not visited her at the church. He encounters again, later in the film, whilst on a bender with Woitech; this time, however, the encounter is presented more ambiguously, the girl Andreas believes to be Saint Thérèse telling him she is simply waiting for her parents to return from Mass. Andreas’ encounter with the wealthy Christian gentleman on the steps near the bank of the Seine precipitates Andreas’ growing awareness of his status as a moral creature, this awareness allowing Andreas to slowly ease himself out of his state of permanent alcoholic ‘fuzz’. Precipitated by the Christian’s offer to ‘loan’ him 200 francs, Andreas becomes insistent in declaring that, despite his appearance, he is an honourable man. ‘I gave you my word’, Andreas tells the Christian, ‘I will keep my word’. (‘I must assure you I am still an honourable man’, Andreas tells the same man when he encounters him near the end of the picture.) Even after Andreas has acquired new clothes and bathed, throughout the picture his hands remain dirty: they become an index of his poverty. When he encounters the tailor who offers to pay Andreas to help move his belongings, Andreas declares that he is an honourable man despite his appearance – and holds up his dirty hands so that the tailor may see them. The tailor recognises the symbolism of this gesture and nods and smiles in acknowledgement of Andreas’ assertion that he is a man of honour and responsibility. Despite his repeated failure to pay his debt to Saint Thérèse, Andreas becomes increasingly convinced of divine providence – especially after he is ‘visited’ by Saint Thérèse as he sleeps under the bridge over the Seine, a visit during which she asks him why Andreas has not visited her at the church. He encounters again, later in the film, whilst on a bender with Woitech; this time, however, the encounter is presented more ambiguously, the girl Andreas believes to be Saint Thérèse telling him she is simply waiting for her parents to return from Mass.

Likewise, the film has a strong element of non-linearity, interweaving into the main narrative glimpses of Andreas’ life before his descent into alcoholism: departing on the train, his father giving him a pocket watch which Andreas continues to carry with him as a metonym for his past respectability (removing it from its case and caressing it in a pub during a late sequence in the film); his remembrances of his love affair with Karoline; very brief shots showing Andreas in his work as a miner. These brief moments of analepsis, fragmented and impressionistic, are wordless and accompanied by lyrical music; in the manner in which they appear in the narrative, they recall Sergio Leone’s interweaving of past and present in Once Upon a Time in America (1984). Along with the appearance of Saint Thérèse under the bridge over the Seine, the flashbacks convey something of the qualities of magical realism upon Olmi’s interpretation of Roth’s novella. The flashbacks seem to place in juxtaposition the simply naïve idealism of youth and the harsher realities of middle-age. In his harsh present, Andreas recollects a prior time of simple pleasures, love, warmth, companionship and happiness. Fairly late in the film, we are shown a flashback in which Andreas stands outside a house as a woman runs out of it; she is chased by an aggressive man. Andreas simply pushes the man backwards, and the man becomes impaled on the garden fence where he dies. This, we are led to believe, is the principal reason why Andreas has gone ‘off grid’ (to use modern parlance) and fallen into a transient lifestyle. (In the novella, Andreas has served a sentence in prison for his role in causing this man’s death.) Likewise, the film has a strong element of non-linearity, interweaving into the main narrative glimpses of Andreas’ life before his descent into alcoholism: departing on the train, his father giving him a pocket watch which Andreas continues to carry with him as a metonym for his past respectability (removing it from its case and caressing it in a pub during a late sequence in the film); his remembrances of his love affair with Karoline; very brief shots showing Andreas in his work as a miner. These brief moments of analepsis, fragmented and impressionistic, are wordless and accompanied by lyrical music; in the manner in which they appear in the narrative, they recall Sergio Leone’s interweaving of past and present in Once Upon a Time in America (1984). Along with the appearance of Saint Thérèse under the bridge over the Seine, the flashbacks convey something of the qualities of magical realism upon Olmi’s interpretation of Roth’s novella. The flashbacks seem to place in juxtaposition the simply naïve idealism of youth and the harsher realities of middle-age. In his harsh present, Andreas recollects a prior time of simple pleasures, love, warmth, companionship and happiness. Fairly late in the film, we are shown a flashback in which Andreas stands outside a house as a woman runs out of it; she is chased by an aggressive man. Andreas simply pushes the man backwards, and the man becomes impaled on the garden fence where he dies. This, we are led to believe, is the principal reason why Andreas has gone ‘off grid’ (to use modern parlance) and fallen into a transient lifestyle. (In the novella, Andreas has served a sentence in prison for his role in causing this man’s death.)

Like the Christian before him, Andreas becomes convinced of the possibility of miracles through the series of fortunate events that befall him following his contact with the Christian and the tale of Saint Thérèse. ‘In the last few days, I’m really starting to believe in miracles’, Andreas tells Karoline when the pair are reunited. The pair spend the evening in a dance hall, a near-empty place illuminated by the blue night of a winter’s evening which falls through huge circular windows onto the wooden dance floor. The image becomes a space of the mind, metonymic of Andreas’ life, the light cast through the windows both dispelling and amplifying the shadows like the faith Andreas has encountered.

Video

The film is presented uncut, with a running time of 127:36 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film is presented uncut, with a running time of 127:36 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The film’s photography, by Dante Spinotti, is breathtaking at times. Like many of the other films Spinotti has shot, The Legend of the Holy Drinker makes much use of shots framed through glass or reflections in mirrors, offering a slight sense of distortion in some of the compositions. The opening sequence, which details the bridge under the Seine where Andreas sleeps, sees the city bathed in amber light that is reminiscent of hellfire. As Andreas ‘sobers up’, the palette becomes more naturalistic and ‘straight’. The film then oscillates between nighttime scenes (bathed in amber, green and blue light) and naturalistically filmed daytime scenes. Arrow’s new presentation is a 4k restoration based on the original negative. The presentation is absolutely superb. Detail is resolved excellently, close-ups of the actors’ faces showing a strong level of fine detail. Colours are rich and vibrant where they need to be (for example, in the aforementioned nighttime scenes) and muted and naturalistic in the daytime scenes. There is no damage to speak of, and contrast levels are excellent, midtones being rich and defined and shadows tapering off into deep blacks. Finally, a strong encode ensures the presentation looks film-like throughout, retaining the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with several audio options: (i) an English DTS-HD 5.1 track; (ii) an English LPCM 2.0 stereo track; and (iii) an Italian LPCM 2.0 stereo track. The 5.1 track features added sound separation which is atmospheric but the sound mix seems quite muted at ties, whereas the English LPCM 2.0 rack is richer and more vibrant. The Italian track features heavier bass, however. All tracks are fine, though the English sound mix is perhaps preferable owing to the presence of Hauer’s distinctive voice. (A few lines in the English track are presented in French, Andreas sometimes struggling to use the language effectively.) Many (all?) of the other dialogue seems to have been shot in English (mouth movements seem to match the English dialogue), though secondary roles feature English dialogue which is sometimes a little stilted and ‘off’ in its delivery – but that arguably helps the picture, contributing to a sense of alienation and discomfort that communicates Andreas’ position within the narrative. Optional English subtitles, and alternate subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, are included. These are easy to read and free from errors, though the lines of dialogue in French are not translated in the subtitles. The disc presents the viewer with several audio options: (i) an English DTS-HD 5.1 track; (ii) an English LPCM 2.0 stereo track; and (iii) an Italian LPCM 2.0 stereo track. The 5.1 track features added sound separation which is atmospheric but the sound mix seems quite muted at ties, whereas the English LPCM 2.0 rack is richer and more vibrant. The Italian track features heavier bass, however. All tracks are fine, though the English sound mix is perhaps preferable owing to the presence of Hauer’s distinctive voice. (A few lines in the English track are presented in French, Andreas sometimes struggling to use the language effectively.) Many (all?) of the other dialogue seems to have been shot in English (mouth movements seem to match the English dialogue), though secondary roles feature English dialogue which is sometimes a little stilted and ‘off’ in its delivery – but that arguably helps the picture, contributing to a sense of alienation and discomfort that communicates Andreas’ position within the narrative. Optional English subtitles, and alternate subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, are included. These are easy to read and free from errors, though the lines of dialogue in French are not translated in the subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes: - An interview with Rutger Hauer (9:20). In a new interview, Hauer discusses the film. He begins by offering a summary of the film’s narrative and themes. He talks about his meeting with Olmi, who described the picture as ‘an action movie, but on your face’. Hauer suggests the picture offered a challenge to him as an actor, differing from the action roles with which he had come to be associated. - An interview with screenwriter Tullio Kezich (25:47). This is an older interview, recorded on videotape, in which Kezich is interviewed by Tonino Pinto. The pair speak in Italian, with optional English subtitles. They reflect on the film’s origins in Roth’s novella, talking about Roth’s work and career. Kezich discusses working with Olmi and crafting the script for the film, discussing some of the ways in which passages from Roth’s novella were visualised.

Overall

Given the context in which it was written, its posthumous publication and the manner in which the story resolves itself, it’s difficult not to read Joseph Roth’s source novella as autobiographical. Certainly, the story of Andreas’ continually frustrated attempts to redeem himself gain added resonance when one considers the novella’s relationship with Roth’s life. Olmi’s film communicates the texture of a drunken state very well, employing non-linearity and subtle fantastical elements in a manner that invites comparisons with magical realism. As a story of down-and-outs, the film has some interesting contemporaneous brethren, including the aforementioned Barfly and Les amants du Pont-Neuf. There are also some strong similarities with – and you may need to bear with me for a few moments – Abel Ferrara’s King of New York (1989), and perhaps even Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant (1992). Like Roth’s novella (and of course, Olmi’s film adaptation), King of New York details its protagonists (Frank White, played by Christopher Walken) attempts at redemption punctuated by references to Catholicism, ultimately culminating in his death. (Bad Lieutenant has a similar narrative trajectory and features a similar focus on faith and a climax which features the death of its protagonist.) Though the novel was fifty years old at the time this adaptation was made, its themes of destitution and redemption were profoundly relevant to the zeitgeist of the mid/late-1980s. Given the context in which it was written, its posthumous publication and the manner in which the story resolves itself, it’s difficult not to read Joseph Roth’s source novella as autobiographical. Certainly, the story of Andreas’ continually frustrated attempts to redeem himself gain added resonance when one considers the novella’s relationship with Roth’s life. Olmi’s film communicates the texture of a drunken state very well, employing non-linearity and subtle fantastical elements in a manner that invites comparisons with magical realism. As a story of down-and-outs, the film has some interesting contemporaneous brethren, including the aforementioned Barfly and Les amants du Pont-Neuf. There are also some strong similarities with – and you may need to bear with me for a few moments – Abel Ferrara’s King of New York (1989), and perhaps even Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant (1992). Like Roth’s novella (and of course, Olmi’s film adaptation), King of New York details its protagonists (Frank White, played by Christopher Walken) attempts at redemption punctuated by references to Catholicism, ultimately culminating in his death. (Bad Lieutenant has a similar narrative trajectory and features a similar focus on faith and a climax which features the death of its protagonist.) Though the novel was fifty years old at the time this adaptation was made, its themes of destitution and redemption were profoundly relevant to the zeitgeist of the mid/late-1980s.

Olmi’s The Legend of the Holy Drinker is beautifully photographed by Dante Spinotti and anchored by a superb performance from Rutger Hauer; Hauer is required to be in an almost perpetual drunken state throughout the film, and he does this exceptionally well. The film is a delight to behold, and Arrow’s new presentation is absolutely superb, translating the film’s photography deliciously to high definition digital home video. The extremely pleasing presentation of the main feature is accompanied by some good contextual material in the form of interviews with Hauer and screenwriter Tullio Kezich. This is a very good release of a film which despite the critical acclaim with which it was received, has been sadly neglected on home video formats in the UK, and comes with a very strong recommendation.

|

|||||

|