|

|

Thing (The) AKA John Carpenter's The Thing (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th November 2017). |

|

The Film

The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982) The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982)

A loose remake of Howard Hawks’ Cold War-era science fiction monster picture The Thing From Another World (1951), John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) has itself been the subject of a more recent remake/prequel by Matthijs van Heijningen in 2011. Carpenter’s film was made during a decade (the 1980s) in which there were a number of reimaginings of Cold War-era science fiction films: for example, David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly and Tobe Hooper’s remake of Invaders from Mars (both 1986). Carpenter’s film benefitted greatly from some superb photography by Dean Cundey and visceral effects work from Rob Bottin, and whereas the 1951 film offers a monster which represents an external threat, Carpenter’s The Thing contains instead a monster which represents a threat from within. Carpenter’s The Thing focuses on an American Antarctic research station, Outpost 31, whose peace is suddenly shattered by the arrival of a husky. The husky is followed by a helicopter from a nearby Norwegian camp; the Norwegians are shooting at the dog. The helicopter lands; the pilot is killed when a thermite grenade accidentally detonates, and his compatriot attempts to shoot the dog but hits instead Bennings (Peter Malone), one of the Americans. In response, Garry (Donald Moffat) shoots the surviving Norwegian with the revolver he carries. The husky is taken into the camp by Clark (Richard Masur), the American team’s dog handler. Meanwhile, Outpost 31’s helicopter pilot, MacReady (Kurt Russell) flies out to the Norwegian camp with Copper (Richard Dysart), the research station’s doctor. There, they discover the camp deserted and partially-demolished. Amidst the ruins is a videotape which shows the Norwegian team using thermite to expose an alien spacecraft buried in the ice. The Norwegians also seem to have discovered a body apparently thrown from the craft, a distorted humanoid corpse that is frozen in a block of ice.  At night, in the dog pound, the strange husky begins to transform; tendrils shoot out of its body and ensnare the other dogs. The human members of the camp come to an awareness of what is taking place, and faced with the alien threat MacReady makes the decision to use the camp’s flamethrower to eliminate it. However, before he can do so the creature bursts out of the pen and escapes. At night, in the dog pound, the strange husky begins to transform; tendrils shoot out of its body and ensnare the other dogs. The human members of the camp come to an awareness of what is taking place, and faced with the alien threat MacReady makes the decision to use the camp’s flamethrower to eliminate it. However, before he can do so the creature bursts out of the pen and escapes.

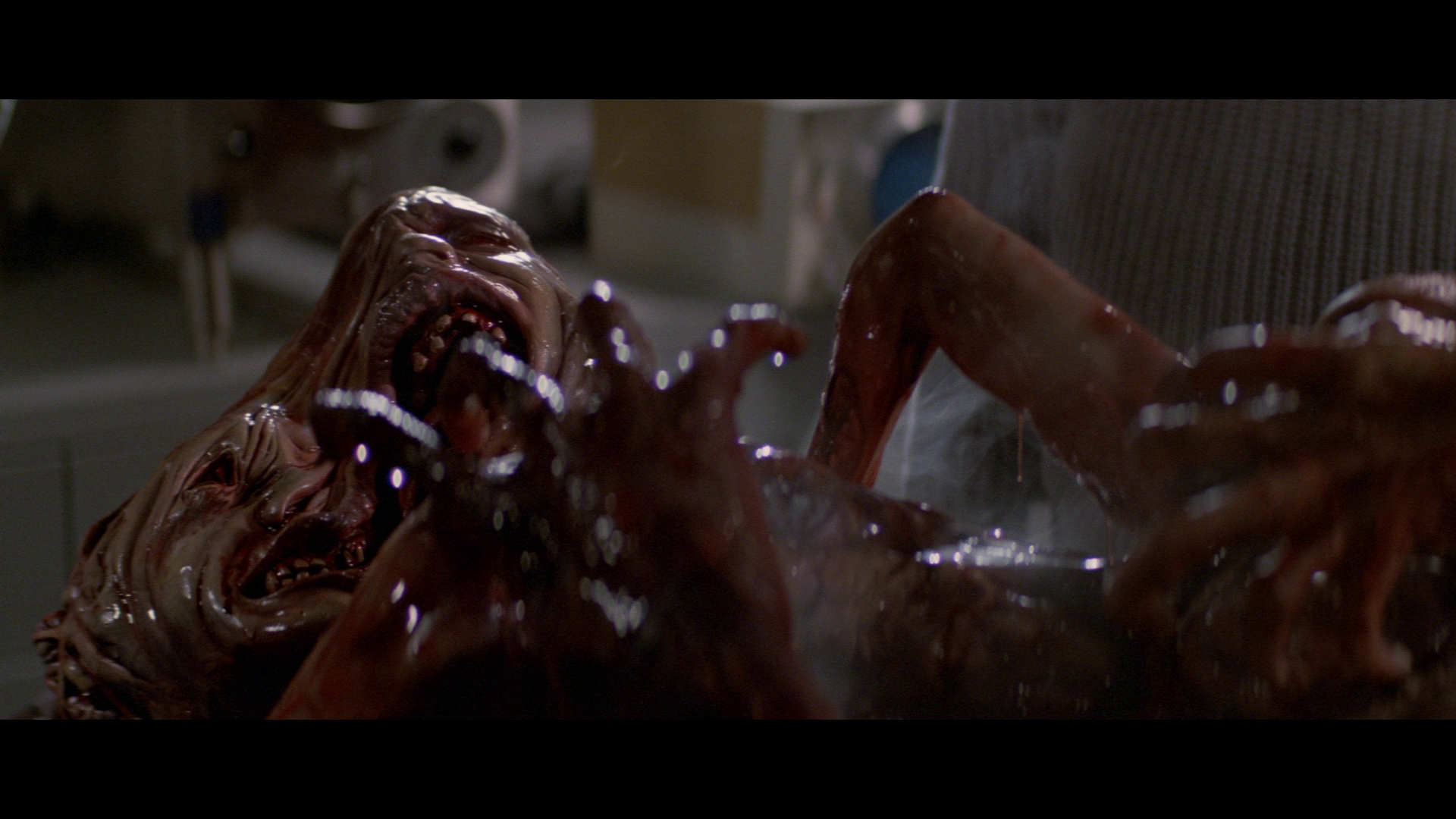

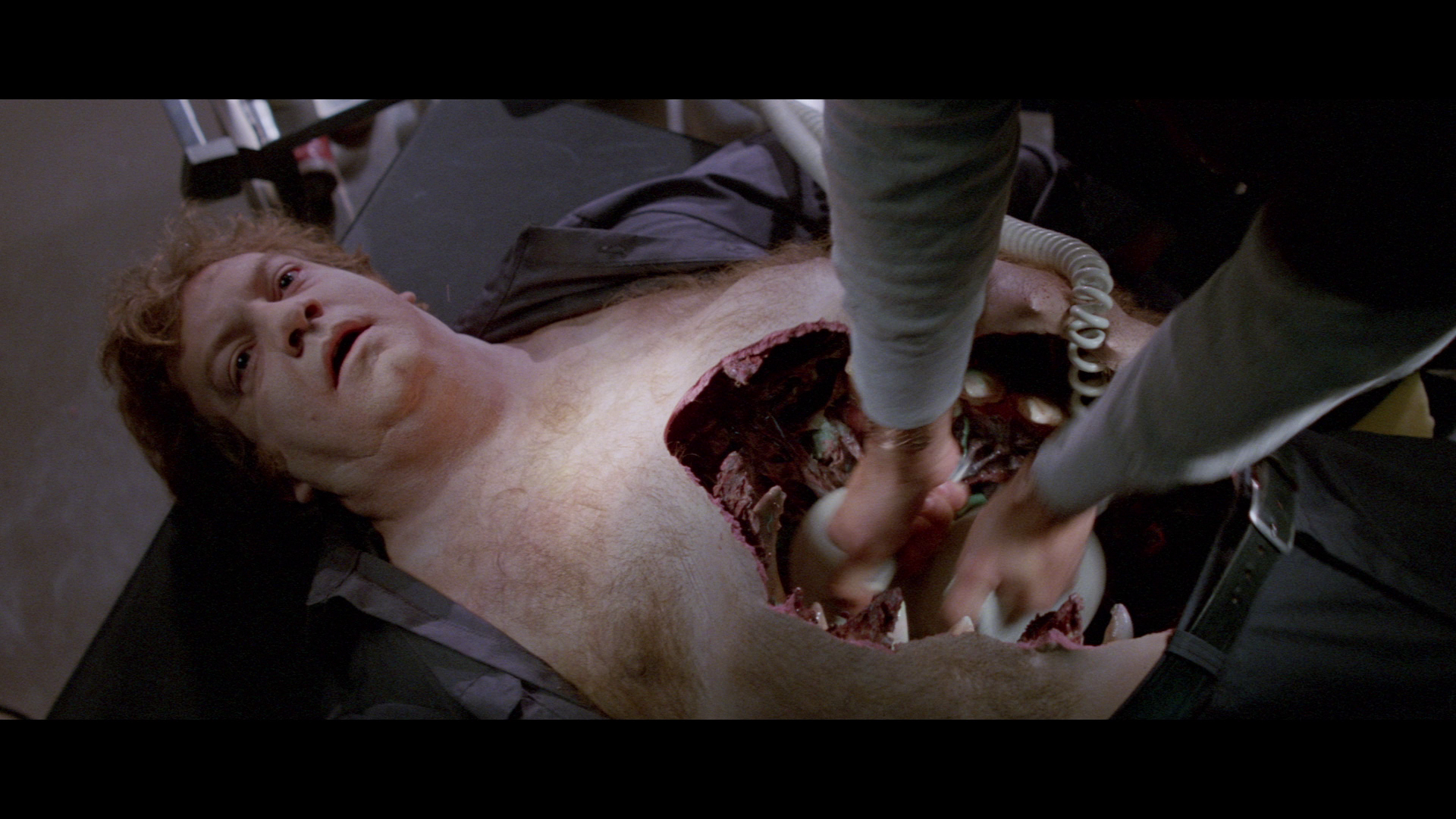

Blair performs an autopsy on the remains of the camp’s dogs and surmises that the alien creature was in the process of assimilating and mimicking them: that if, left unchallenged, the creature would have absorbed the dogs on a cellular level and imitated them perfectly. Armed with this knowledge, the research team begin to suspect one another of being assimilated and taken over by the alien. One by one, the alien begins to attack and mimic the members of the team; the first of these victims is Bennings, and the alien creature is interrupted mid-transformation. Taking action, MacReady burns the Bennings-thing with kerosene. However, a number of other members of the team have already been ‘infected’. During an angry confrontation, one member of the team, Norris (Charles Hallahan), appears to suffer a heart attack. Doc Copper tries to save Norris’ life by using a defibrillator. However, Norris is revealed to be an imitation; as Copper presses the defibrillator to Norris’ chest, Norris’ chest cavity opens as if it were a mouth and swallows Copper’s hands. MacReady destroys the Norris-thing using the flamethrower, but the surviving members of the team watch in horror as Norris’ head detaches from his body, sprouts eight legs and antennae and scuttles across the floor like a spider.  After watching the Norris-thing’s head detach from its body and transform in an attempt to flee from the fire, MacReady surmises that one single cell of the alien creature is enough to absorb and replicate a living organism on the cellular level, and that each part of ‘the thing’ operates independently and will attempt to protect itself if threatened. Armed with this knowledge, the paranoid MacReady, convinced that a number of his colleagues are alien imitations, devises a blood serum test which he hopes will identify which of the survivors are ‘things’ and which are human. MacReady intends to take a sample of blood from each of the survivors and, using a flamethrower, heat a piece of wire coil before inserting it into each blood sample. MacReady believes that blood from a ‘thing’ will react to this, thus allowing him to identify which of his colleagues has been infected. The sequence establishes its equilibrium with MacReady’s outlining of his intention with the blood serum test. As MacReady works through the various blood samples, revealing their donors to be human, the film lulls the characters (and the audience) into a false sense of security: the characters who MacReady believed to have been taken over by the alien are gradually revealed to be human, including Clark, whom MacReady shot when Clark attempted to attack MacReady with a scalpel. However, the blood from one of the characters whom MacReady believed to be human, Palmer (David Clennon), reacts to the insertion of the heated wire by leaping from the Petri dish in which it is contained. In response to this, the Palmer-thing begins to transform. The Palmer-thing attacks Windows (Thomas G Waites), who has been assisting MacReady in the administering of the blood serum test and who freezes when faced with the alien threat. MacReady destroys the Palmer-thing with the flamethrower, but he is too late to save Windows and is forced to turn the flamethrower on him too. The sequence achieves its resolution, and a restoration of equilibrium, when MacReady returns to administer the test and discovers that the rest of the survivors are human. After watching the Norris-thing’s head detach from its body and transform in an attempt to flee from the fire, MacReady surmises that one single cell of the alien creature is enough to absorb and replicate a living organism on the cellular level, and that each part of ‘the thing’ operates independently and will attempt to protect itself if threatened. Armed with this knowledge, the paranoid MacReady, convinced that a number of his colleagues are alien imitations, devises a blood serum test which he hopes will identify which of the survivors are ‘things’ and which are human. MacReady intends to take a sample of blood from each of the survivors and, using a flamethrower, heat a piece of wire coil before inserting it into each blood sample. MacReady believes that blood from a ‘thing’ will react to this, thus allowing him to identify which of his colleagues has been infected. The sequence establishes its equilibrium with MacReady’s outlining of his intention with the blood serum test. As MacReady works through the various blood samples, revealing their donors to be human, the film lulls the characters (and the audience) into a false sense of security: the characters who MacReady believed to have been taken over by the alien are gradually revealed to be human, including Clark, whom MacReady shot when Clark attempted to attack MacReady with a scalpel. However, the blood from one of the characters whom MacReady believed to be human, Palmer (David Clennon), reacts to the insertion of the heated wire by leaping from the Petri dish in which it is contained. In response to this, the Palmer-thing begins to transform. The Palmer-thing attacks Windows (Thomas G Waites), who has been assisting MacReady in the administering of the blood serum test and who freezes when faced with the alien threat. MacReady destroys the Palmer-thing with the flamethrower, but he is too late to save Windows and is forced to turn the flamethrower on him too. The sequence achieves its resolution, and a restoration of equilibrium, when MacReady returns to administer the test and discovers that the rest of the survivors are human.

Although it is usually identified as a remake of Howard Hawks’ 1951 film, Carpenter’s The Thing is substantially different from that earlier monster picture and closer in spirit to the novella on which both films are based, John W Campbell Jr’s Who Goes There? (1938). Whilst there are similarities between the two adaptations (a crashed alien spaceship, a creature frozen in ice which thaws and threatens the American crew of an Antarctic research station), in Hawks’ film the alien creature represents an external threat and offers a more traditional film ‘monster’: a hulking creature, an evolved form of sentient plant life that is described in the film’s dialogue as ‘an intellectual carrot’. Jez Conolly describes the creature in Hawks’ film as ‘an embodiment of non-American otherness at a time of heightened fears about Communism in the United States’ (Conolly, 2013: 36). Hawks’ film has been interpreted as a piece of Cold War propaganda, a ‘warning against naïve blindness to foreign threats’, in which the human (American) characters band together against the alien (Communist) threat (Donovan, 2011: 86).  By contrast, Carpenter’s film shares with Campbell’s source novella a depiction of the alien threat as a shapeshifter, a creature capable of absorbing and replicating any living organism – masquerading as human. In this context, the humans find it difficult to identify which of them may be ‘infected’. In contrast with the external threat depicted within Hawks’ film, Carpenter’s The Thing represents the threat as internal – within the self, and within the group. The focus on the alien’s assimilation and imitation of its human prey pushes Carpenter’s film into the subgenre of body horror: horror films that focus on the deterioration of the human body (such as Cronenberg’s The Fly, which graphically depicts the deterioration of scientist Seth Brundle’s body after a teleportation experiment goes hideously wrong) or depict it as under threat from parasites that modify human behaviour (as in Cronenberg’s Shivers, 1975, in which a scientifically-created parasite causes its hosts to exhibit impulsive, often self-destructive behaviour). In achieving this sense of ‘body horror’, The Thing makes strong use of the makeup effects of Rob Bottin. By contrast, Carpenter’s film shares with Campbell’s source novella a depiction of the alien threat as a shapeshifter, a creature capable of absorbing and replicating any living organism – masquerading as human. In this context, the humans find it difficult to identify which of them may be ‘infected’. In contrast with the external threat depicted within Hawks’ film, Carpenter’s The Thing represents the threat as internal – within the self, and within the group. The focus on the alien’s assimilation and imitation of its human prey pushes Carpenter’s film into the subgenre of body horror: horror films that focus on the deterioration of the human body (such as Cronenberg’s The Fly, which graphically depicts the deterioration of scientist Seth Brundle’s body after a teleportation experiment goes hideously wrong) or depict it as under threat from parasites that modify human behaviour (as in Cronenberg’s Shivers, 1975, in which a scientifically-created parasite causes its hosts to exhibit impulsive, often self-destructive behaviour). In achieving this sense of ‘body horror’, The Thing makes strong use of the makeup effects of Rob Bottin.

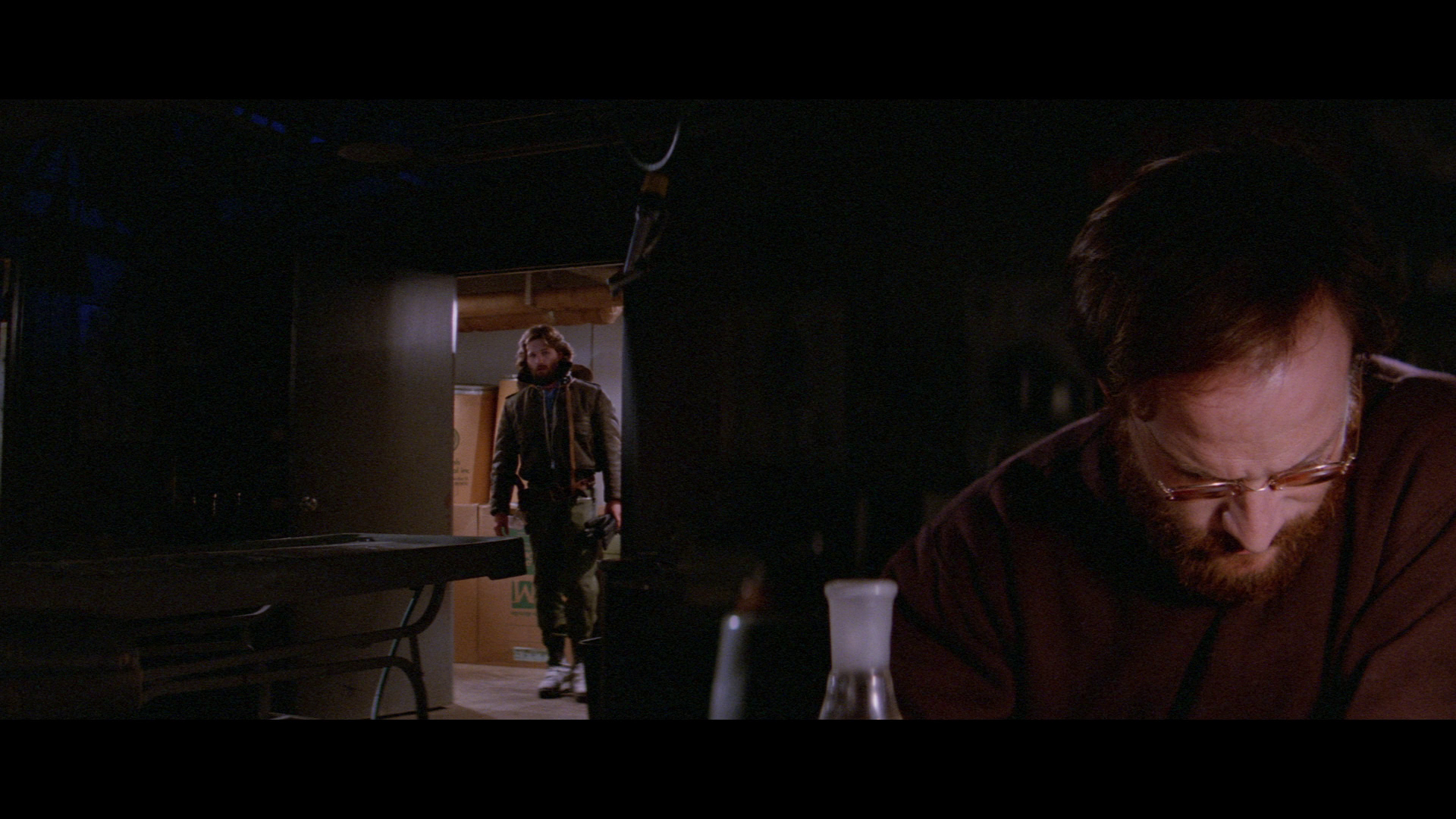

Photographed by Dean Cundey, with whom Carpenter worked on a number of films including Halloween (1978) and The Fog (1980), The Thing was shot in a widescreen format (Panavision); Cundey has expressed that he had previously encountered resistance from directors who felt that the 2.35:1 screen ratio ‘was too wide and you couldn’t really get close-ups of the actors’ (Cundey, quoted in Hemphill, 2015: np). What Cundey attempted to achieve, with Carpenter’s blessing, was to film the close-ups within The Thing in such a way that they used ‘the wide aspect ratio to place characters in an environment’ (Cundey, quoted in ibid.). There was an attempt to use the widescreen frame to shoot the actors in groups and also to suggest a sense of claustrophobia (Cundey, in ibid.). Both types of shot are evident in the pivotal blood serum test sequence, in particular. Throughout much of this specific sequence, MacReady is isolated within the frame: he is filmed standing alone, whilst the other characters are filmed predominantly in groups. As Clark and MacReady regard each other suspiciously, we are presented with a group shot of the other survivors, the five men filling the frame as Garry asserts, ‘Come on, let’s rush him. He’s not going to blow us all up’. A close-up of MacReady’s face reinforces his centrality to the narrative: he is the film’s protagonist, and in this sequence he is in control. This element of composition is reversed at the end of the sequence, after MacReady has proven through his test that Nauls and Childs are human. Here, MacReady is filmed as part of a group which also includes Nauls and Childs, whilst Garry – who is still tied to the sofa – is framed on his own.  Near the beginning of the blood serum test sequence, Clark is filmed in medium shot: MacReady’s attention is turned towards Clark, who MacReady (and some of the other characters) believes to be a ‘thing’. The attention of the audience is focused on MacReady, as is the attention of the film’s other characters. Presented in medium shot, Clark is isolated from both MacReady and the other survivors; he approaches MacReady and calmly mocks him (‘Let’s do what Mac says. I mean, he wasted Norris pretty quick, didn’t he?’). A low-angle deep focus shot draws the audience’s attention to Clark’s hand, in which he conceals a scalpel; as MacReady is challenged by Childs (Keith David), his attention drawn away from Clark, close-ups of MacReady are alternated with close-ups of Childs, establishing the temporary conflict between these two characters (‘Then I’m going to have to kill you, Childs’, MacReady says). After Clark’s unsuccessful attempt to overpower MacReady with the scalpel, a high-angle close-up of the dead Clark’s face foregrounds the extraordinary precision of MacReady’s gunshot (the bullet having struck Clark dead centre in his forehead). As MacReady outlines his plan, Cundey’s camera roves amongst the actors, picking out close-ups that show their reactions to it: ‘I’m going to draw a little bit of everybody’s blood. I’m gonna find out who’s the thing. Watching Norris in there gave me the idea that maybe every part of him was a whole, every little piece was an individual animal, with a built in desire to protect its own life’. The dialogue reinforces the tension between the individual and the group that has been established visually, through Cundey’s photography which juxtaposes shots of individuals with shots of groups. Following this, there is a cut once again to a close-up of MacReady, shot from a low-angle to establish his authority, that separates him from the group, and the camera dollies in to his face as he expresses a revelation: ‘You see, when a man bleeds, it’s just tissue. But the blood from one of you things won’t obey when it’s attacked. It’ll try and survive. Crawl away from a hot needle, say’. A high-angle shot, taken from over MacReady’s shoulder, shows the other survivors tied to their chairs, the high angle reinforcing their powerlessness within this scenario. As MacReady tests each blood sample, the Petri dish containing the sample and bearing the name of the character from whom the blood has been taken is shot in close-up, and alternated with a close-up of the relevant character that presents for the audience their reaction (Windows breathes a deep sigh of relief, for example). When MacReady tests the blood of Copper and Clark, a close-up of Nauls shows him turning his head; the camera racks focus to reveal that Nauls is looking at the corpses of Copper and Clark. Near the beginning of the blood serum test sequence, Clark is filmed in medium shot: MacReady’s attention is turned towards Clark, who MacReady (and some of the other characters) believes to be a ‘thing’. The attention of the audience is focused on MacReady, as is the attention of the film’s other characters. Presented in medium shot, Clark is isolated from both MacReady and the other survivors; he approaches MacReady and calmly mocks him (‘Let’s do what Mac says. I mean, he wasted Norris pretty quick, didn’t he?’). A low-angle deep focus shot draws the audience’s attention to Clark’s hand, in which he conceals a scalpel; as MacReady is challenged by Childs (Keith David), his attention drawn away from Clark, close-ups of MacReady are alternated with close-ups of Childs, establishing the temporary conflict between these two characters (‘Then I’m going to have to kill you, Childs’, MacReady says). After Clark’s unsuccessful attempt to overpower MacReady with the scalpel, a high-angle close-up of the dead Clark’s face foregrounds the extraordinary precision of MacReady’s gunshot (the bullet having struck Clark dead centre in his forehead). As MacReady outlines his plan, Cundey’s camera roves amongst the actors, picking out close-ups that show their reactions to it: ‘I’m going to draw a little bit of everybody’s blood. I’m gonna find out who’s the thing. Watching Norris in there gave me the idea that maybe every part of him was a whole, every little piece was an individual animal, with a built in desire to protect its own life’. The dialogue reinforces the tension between the individual and the group that has been established visually, through Cundey’s photography which juxtaposes shots of individuals with shots of groups. Following this, there is a cut once again to a close-up of MacReady, shot from a low-angle to establish his authority, that separates him from the group, and the camera dollies in to his face as he expresses a revelation: ‘You see, when a man bleeds, it’s just tissue. But the blood from one of you things won’t obey when it’s attacked. It’ll try and survive. Crawl away from a hot needle, say’. A high-angle shot, taken from over MacReady’s shoulder, shows the other survivors tied to their chairs, the high angle reinforcing their powerlessness within this scenario. As MacReady tests each blood sample, the Petri dish containing the sample and bearing the name of the character from whom the blood has been taken is shot in close-up, and alternated with a close-up of the relevant character that presents for the audience their reaction (Windows breathes a deep sigh of relief, for example). When MacReady tests the blood of Copper and Clark, a close-up of Nauls shows him turning his head; the camera racks focus to reveal that Nauls is looking at the corpses of Copper and Clark.

MacReady moves on to testing the blood of Palmer. Lulled into a false sense of security by the so-far negative results of the blood tests, MacReady holds the Petri dish containing Palmer’s blood in the palm of his hand. A close-up of Palmer establishes his unfazed reaction to the proceedings, again suggesting to the audience that this test will proceed as the ones before it, something which is reinforced by Garry’s very vocal questioning of the validity of MacReady’s test (‘This is pure nonsense. It doesn’t prove a thing’). The subsequent low-angle shot of MacReady once again establishes his power within the sequence, though this is suddenly undercut by the reaction that Palmer’s blood exhibits when MacReady touches it with the hot wire. As Palmer begins his transformation, he is presented in a group shot which frames Palmer on the right hand side of the frame whilst, to the left of him, Garry, Childs and Nauls react to the realisation that Palmer has been infected. A medium shot of MacReady reveals his flamethrower to be malfunctioning; next to him, on the right hand side of the frame, the board behind the pinball machine reads ironically ‘HEAT WAVE’. As Palmer begins to transform, a close-up of the actor is followed by a medium shot of MacReady, before returning to a close-up of the animatronic puppet that Rob Bottin created for the transformation sequence – the transition from one to the other concealed by a Melies-style cutaway to a shot of MacReady. As the Palmer-thing attaches itself to the ceiling of the cabin, Windows is transfixed by it; Windows’ failure to act is underscored by the high-angle shot of him, symbolising his helplessness, and the power that has now transferred from MacReady to the Palmer-thing is represented through the low-angle shots of the Palmer-thing as it is attached to the ceiling and, shortly after, as its head splits open in front of the horrified Windows. Here, Rob Bottin’s effects are both horrifyingly authentic-looking and so excessive in their depiction of the body-in-pieces as to be considered surreal. MacReady moves on to testing the blood of Palmer. Lulled into a false sense of security by the so-far negative results of the blood tests, MacReady holds the Petri dish containing Palmer’s blood in the palm of his hand. A close-up of Palmer establishes his unfazed reaction to the proceedings, again suggesting to the audience that this test will proceed as the ones before it, something which is reinforced by Garry’s very vocal questioning of the validity of MacReady’s test (‘This is pure nonsense. It doesn’t prove a thing’). The subsequent low-angle shot of MacReady once again establishes his power within the sequence, though this is suddenly undercut by the reaction that Palmer’s blood exhibits when MacReady touches it with the hot wire. As Palmer begins his transformation, he is presented in a group shot which frames Palmer on the right hand side of the frame whilst, to the left of him, Garry, Childs and Nauls react to the realisation that Palmer has been infected. A medium shot of MacReady reveals his flamethrower to be malfunctioning; next to him, on the right hand side of the frame, the board behind the pinball machine reads ironically ‘HEAT WAVE’. As Palmer begins to transform, a close-up of the actor is followed by a medium shot of MacReady, before returning to a close-up of the animatronic puppet that Rob Bottin created for the transformation sequence – the transition from one to the other concealed by a Melies-style cutaway to a shot of MacReady. As the Palmer-thing attaches itself to the ceiling of the cabin, Windows is transfixed by it; Windows’ failure to act is underscored by the high-angle shot of him, symbolising his helplessness, and the power that has now transferred from MacReady to the Palmer-thing is represented through the low-angle shots of the Palmer-thing as it is attached to the ceiling and, shortly after, as its head splits open in front of the horrified Windows. Here, Rob Bottin’s effects are both horrifyingly authentic-looking and so excessive in their depiction of the body-in-pieces as to be considered surreal.

Rob Bottin was not Carpenter’s first choice for the project: he had originally approached Dale Kuipers to produce the film’s makeup effects, but Kuipers fell ill and had to leave the production (Billson, 1997: 49). Bottin picked up the reins and told Carpenter that ‘the audience has great expectations about what a monster from outer space would be. When it turns out to be a guy in a suit – or a guy in a bug costume – it just isn’t going to cut it now, because people want to see more’ (Bottin, quoted in ibid.). Bottin developed the characteristics of the shape-shifting monster, suggesting that it was able to display elements of creatures from other planets it may have visited (Carpenter, quoted in ibid.). Bottin’s depiction of the contortions of the human (and alien) bodies within the film as they undergo transformations has been identified by some commentators as sharing characteristics with surrealist art, and in particular the work of the late-Nineteenth Century artist Odilon Redon (Mulvey-Roberts, 2004: 96). Bottin suggested that he attempted to show some restraint within his work on The Thing, trying to steer away from gore that was too graphic: ‘If you had blood spurting all over in some of these scenes, I think you’d make people chuck’, he said in interview (Bottin, quoted in Billson, 1997: 75). In the scene in which the Norris-thing’s head detaches from its body, Bottin used green and yellow fluids instead of red blood, stating that the scene is so excessive that it is ‘not splatter. That’s a Walt Disney imagination: it’s not gross, it’s fun!’ (Bottin, quoted in ibid.). In the blood serum test sequence, the Palmer-thing’s transformation was achieved via an animatronic puppet, and with the awareness that the effects work could go ‘too far’, Bottin and Carpenter chose to cut the finished effects scene slightly, removing a shot of the Palmer-thing’s head splitting apart to reveal a second face beneath it, which then in turn splits apart to reveal the tendril that attaches itself to Windows’ neck and draws him into the creature’s jaws. Rob Bottin was not Carpenter’s first choice for the project: he had originally approached Dale Kuipers to produce the film’s makeup effects, but Kuipers fell ill and had to leave the production (Billson, 1997: 49). Bottin picked up the reins and told Carpenter that ‘the audience has great expectations about what a monster from outer space would be. When it turns out to be a guy in a suit – or a guy in a bug costume – it just isn’t going to cut it now, because people want to see more’ (Bottin, quoted in ibid.). Bottin developed the characteristics of the shape-shifting monster, suggesting that it was able to display elements of creatures from other planets it may have visited (Carpenter, quoted in ibid.). Bottin’s depiction of the contortions of the human (and alien) bodies within the film as they undergo transformations has been identified by some commentators as sharing characteristics with surrealist art, and in particular the work of the late-Nineteenth Century artist Odilon Redon (Mulvey-Roberts, 2004: 96). Bottin suggested that he attempted to show some restraint within his work on The Thing, trying to steer away from gore that was too graphic: ‘If you had blood spurting all over in some of these scenes, I think you’d make people chuck’, he said in interview (Bottin, quoted in Billson, 1997: 75). In the scene in which the Norris-thing’s head detaches from its body, Bottin used green and yellow fluids instead of red blood, stating that the scene is so excessive that it is ‘not splatter. That’s a Walt Disney imagination: it’s not gross, it’s fun!’ (Bottin, quoted in ibid.). In the blood serum test sequence, the Palmer-thing’s transformation was achieved via an animatronic puppet, and with the awareness that the effects work could go ‘too far’, Bottin and Carpenter chose to cut the finished effects scene slightly, removing a shot of the Palmer-thing’s head splitting apart to reveal a second face beneath it, which then in turn splits apart to reveal the tendril that attaches itself to Windows’ neck and draws him into the creature’s jaws.

Cundey’s photography for The Thing features careful use of the widescreen frame and expressionistic lighting to create suspense and to ‘carry’ Bottin’s effects work. Cundey has said that Bottin’s effects required careful lighting so as not to ‘relegate it to silhouettes’ and ensure that the audience recognised Bottin’s ‘sculpting as so great that we needed to see the creature’, but he was also aware that ‘if we went too far [in lighting the transformation effects], we could give away the fact that it was a lump of plastic with paint on it’ (Cundey, quoted in Hemphill, 2015: np). Each ‘encounter’ with the shape-shifting alien was carefully situated within ‘an area where we could justify using a number of very, very small lights that would highlight areas, surfaces and textures. Then I would light the back of the wall set so that you could see the shape of the creature’: a balance was struck between ‘showing just enough for the audience to understand what was happening while still keeping the creature a little mysterious’ (Cundey, quoted in ibid.). This is evident within the transformation depicted in the blood serum test sequence, with the animatronic puppet depicting the Palmer-thing’s transformation being filmed in close-up but lit with much more noticeably low-key lighting than the other close-ups within the sequence, allowing the audience to see enough of Bottin’s transformation effects to ‘carry’ the impact of what is taking place, reinforced by cutaways to medium shots of the other men who are tied to the sofa trying to pull away from the Palmer-thing, whilst not revealing so much of the effect as to highlight its artificiality. Cundey’s photography for The Thing features careful use of the widescreen frame and expressionistic lighting to create suspense and to ‘carry’ Bottin’s effects work. Cundey has said that Bottin’s effects required careful lighting so as not to ‘relegate it to silhouettes’ and ensure that the audience recognised Bottin’s ‘sculpting as so great that we needed to see the creature’, but he was also aware that ‘if we went too far [in lighting the transformation effects], we could give away the fact that it was a lump of plastic with paint on it’ (Cundey, quoted in Hemphill, 2015: np). Each ‘encounter’ with the shape-shifting alien was carefully situated within ‘an area where we could justify using a number of very, very small lights that would highlight areas, surfaces and textures. Then I would light the back of the wall set so that you could see the shape of the creature’: a balance was struck between ‘showing just enough for the audience to understand what was happening while still keeping the creature a little mysterious’ (Cundey, quoted in ibid.). This is evident within the transformation depicted in the blood serum test sequence, with the animatronic puppet depicting the Palmer-thing’s transformation being filmed in close-up but lit with much more noticeably low-key lighting than the other close-ups within the sequence, allowing the audience to see enough of Bottin’s transformation effects to ‘carry’ the impact of what is taking place, reinforced by cutaways to medium shots of the other men who are tied to the sofa trying to pull away from the Palmer-thing, whilst not revealing so much of the effect as to highlight its artificiality.

The lighting within the film was also carefully designed to ‘create a strong sense of the cold’ by the use of ‘blue tones’, particularly in the exterior scenes; to this end, Cundey used ‘these very intense blue lights used on airport runways’ which ‘threw off an otherworldly blue light’ (Cundey, quoted in Hemphill, 2015: np). For the scenes set within the camp, Cundey had the crew ‘build and hang overhead lights with conical shades’ which allowed them to ‘control the light and not have the rooms completely illuminated’, allowing ‘areas of darkness while still seeing the characters’ (Cundey, quoted in ibid.). Low-key light dominates the blood serum test sequence, for example. Clark is filmed in a medium shot that is lit in a low-key manner; the use of shadows, which seem to surround his face, symbolising the suspicion with which this character is regarded by the film’s anti-hero, MacReady, and some of the other characters. Within the scene, the characters are fringed by blue light which acts as an index of the freezing cold outside the building; this is particularly noticeable in the close-up shot of Clark’s hand just before he attacks MacReady with the scalpel. The blue light here could perhaps be interpreted as a symbol of Clark’s intentions, drawing the audience’s attention away from the group – who are presented on the right hand side of the frame – to Clark’s hand and the object held within it. The lighting within the film was also carefully designed to ‘create a strong sense of the cold’ by the use of ‘blue tones’, particularly in the exterior scenes; to this end, Cundey used ‘these very intense blue lights used on airport runways’ which ‘threw off an otherworldly blue light’ (Cundey, quoted in Hemphill, 2015: np). For the scenes set within the camp, Cundey had the crew ‘build and hang overhead lights with conical shades’ which allowed them to ‘control the light and not have the rooms completely illuminated’, allowing ‘areas of darkness while still seeing the characters’ (Cundey, quoted in ibid.). Low-key light dominates the blood serum test sequence, for example. Clark is filmed in a medium shot that is lit in a low-key manner; the use of shadows, which seem to surround his face, symbolising the suspicion with which this character is regarded by the film’s anti-hero, MacReady, and some of the other characters. Within the scene, the characters are fringed by blue light which acts as an index of the freezing cold outside the building; this is particularly noticeable in the close-up shot of Clark’s hand just before he attacks MacReady with the scalpel. The blue light here could perhaps be interpreted as a symbol of Clark’s intentions, drawing the audience’s attention away from the group – who are presented on the right hand side of the frame – to Clark’s hand and the object held within it.

Discussing the film’s mise-en-scene, Cundey has said that Carpenter strove to find ‘very authentic-looking locations as opposed to just building exteriors on the studio lot’ (Cundey, quoted in Hemphill, 2015: np). This sense of authenticity is communicated through the mise-en-scene within the camp. The rooms within the camp have a ‘lived-in’ appearance, filled with the clutter and detritus of everyday life: the posters on the wall, the pool table in the background, board games stacked on the floor, a jukebox and a pinball machine. The blood serum test sequence, for example, begins with a close-up of a chair onto which a length of rope is thrown; the rope could be said to be metonymic of the broader sense of entrapment experienced by the characters, who are trapped within the camp, unable to escape from the alien threat. Although by the end of the sequence, the human survivors have been identified, the ropes that bind them have been removed and the threat represented by the alien has been temporarily quelled, as the sequence ends the characters are still trapped by their environment and the awareness that the alien creature may still be within the camp. The sense of stasis, a lack of forward movement, is reinforced by Garry’s angry declaration – which begins calmly but becomes increasingly anxious – that ‘I know you gentlemen have been through a lot, but when you find the time, I’d rather not spend the rest of this winter tied to this fucking couch!’  John Carpenter’s The Thing offers a reinterpretation of the classic science fiction monster movie that was defined by 1950s pictures such as Hawks’ The Thing From Another World. Carpenter’s version of The Thing depicts the threat as coming from within rather than from outside: the alien takes over the individual, offering a threat that is located both within the human group and within the human body itself. This sense of an assault upon the body is reinforced by Rob Bottin’s effects work, which pushes the film into the realm of body horror. The depiction of the film’s ‘monster’ as a shape-shifting alien capable of absorbing and replicating any living organism encourages the audience to question what it means to be human. Anne Billson has suggested that ‘[a]ll sci-fi monster movies are, to some extent, about what it means to be human, as opposed to being an alien from outer space, an android or a machine’; the films often question, ‘at what point in the struggle for survival does a person stop being human and start being a survival machine?’ (Billson, op cit.: 59). Nowhere is this more evident than in The Thing. The sense of paranoia is heightened by a contrast within both the dialogue and the photography between the individual. The lack of closure in the film’s narrative encapsulates the film’s focus on the difficulty of identifying who exactly is a ‘friend’ and who is an ‘enemy’, providing a stark contrast to the easy identification of the monster-as-external-threat in Hawks’ 1951 film. John Carpenter’s The Thing offers a reinterpretation of the classic science fiction monster movie that was defined by 1950s pictures such as Hawks’ The Thing From Another World. Carpenter’s version of The Thing depicts the threat as coming from within rather than from outside: the alien takes over the individual, offering a threat that is located both within the human group and within the human body itself. This sense of an assault upon the body is reinforced by Rob Bottin’s effects work, which pushes the film into the realm of body horror. The depiction of the film’s ‘monster’ as a shape-shifting alien capable of absorbing and replicating any living organism encourages the audience to question what it means to be human. Anne Billson has suggested that ‘[a]ll sci-fi monster movies are, to some extent, about what it means to be human, as opposed to being an alien from outer space, an android or a machine’; the films often question, ‘at what point in the struggle for survival does a person stop being human and start being a survival machine?’ (Billson, op cit.: 59). Nowhere is this more evident than in The Thing. The sense of paranoia is heightened by a contrast within both the dialogue and the photography between the individual. The lack of closure in the film’s narrative encapsulates the film’s focus on the difficulty of identifying who exactly is a ‘friend’ and who is an ‘enemy’, providing a stark contrast to the easy identification of the monster-as-external-threat in Hawks’ 1951 film.

Video

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of The Thing is based on a 4k restoration of the picture from the original negative, the restoration having been approved by both Carpenter and Cundey. (A competing release appeared in America last year, in 2016, from Shout! Factory and was based on a 2k scan of an interpositive source.) Photographed anamorphically, in Panavision, The Thing is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1; it is also uncut, with a running time of 108:36 mins. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of The Thing is based on a 4k restoration of the picture from the original negative, the restoration having been approved by both Carpenter and Cundey. (A competing release appeared in America last year, in 2016, from Shout! Factory and was based on a 2k scan of an interpositive source.) Photographed anamorphically, in Panavision, The Thing is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1; it is also uncut, with a running time of 108:36 mins.

Arrow’s new HD presentation (a 1080p presentation that uses the AVC codec) is a head-and-shoulders improvement upon the previously-available Blu-ray release(s) from Universal. The fact that Arrow’s release is based on a new 4k scan of the negative ensures the film has a rich level of fine detail without the very slight coarseness in texture communicated via the presentations based on an interpositive source (on both the Universal and, to a lesser extent, Shout! discs, both of which have a slight ‘filtered’ appearance). Arrow’s presentation also benefits from excellent contrast levels, the scan of the negative giving more balanced shadow detail whilst retaining richly defined/structured midtones and even highlights; previous presentations have seen a slightly ‘crushed’ dynamic range, and this is something which is noticeably opened up on Arrow’s new release. The scan of the negative also opened up the framing somewhat, offering a sliver more visual information at the extreme left and right hand sides of the film frame. Colours on Arrow’s release are also more consistent, without the bleeding/fringing that has been seen in previous Blu-ray releases of this film. The presentation has a rich, film-like appearance which is carried by an excellent encode; the structure of 35mm film is present throughout the picture. In total, Arrow’s new negative-sourced presentation offers a big improvement over previous Blu-ray releases, including Shout!’s recent US release, and delivers a more organic, film-like viewing experience.

Audio

Arrow’s disc includes a range of audio tracks: (i) a LPCM 2.0 stereo track; (ii) a DTS-HD MA 4.1 track; and (iii) a more ‘modern’ DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. All three tracks are clear and without issues. Naturally, option (iii) sees a little more emphasis on sound separation, but (ii) is ‘punchier’. The tracks are accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes an incredible range of contextual material, including: The disc includes an incredible range of contextual material, including:

- An audio commentary with John Carpenter and Kurt Russell. This is the same audio commentary that has appeared on the film’s previous DVD and Blu-ray releases, and sees the director and lead actor reminiscing about the film’s production and its lasting reputation. - A second audio commentary with Mike White, Patrick Bromley and ‘El Goro’. This new commentary track sees input from the chaps behind The Projection Booth podcast, the At This Movie podcast and the Talk Without Rhythm podcast. The three commentators are highly enthusiastic about The Thing, offering a gushing fan’s appreciation of the picture that is filled with trivia, including reflections on the film’s relationship with both the screenplay by Bill Lancaster and the more recent 2011 ‘remake’/‘reimagining’. Long-term fans of The Thing will find much of this information familiar, though it’s delivered with good humour and enthusiasm by the commentators. - ‘Who Goes There: In Search of The Thing’ (77:47). A new documentary about The Thing, this looks at Carpenter’s picture in the context of its position as a ‘remake’ (if one can call it that) of the 1951 film - ‘1982: One Amazing Summer’ (27:20). This new documentary reflects on the films released in the summer of 1982 (which of course included The Thing). Commentators include Nathaniel Thompson, John Kenneth Muir and Anthony Taylor; they discuss films such as E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, Conan the Barbarian and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior.

- ‘John Carpenter’s The Thing: Terror Takes Shape’ (84:00). This is the same documentary that appeared on the film’s 2004 DVD release. It’s an excellent, thorough look at the film’s genesis, its production and release, with the cast and crew (including Carpenter himself) reflecting on the picture. There’s some strong consideration of the film’s effects sequences, in particular. - ‘No“Thing” Left Unsaid: Texas Frightmare Panel’ (55:08). This is a recording of a panel discussion focusing on The Thing that took place at Texas Frightmare Weekend earlier in 2017, and which featured input from Dean Cundy, Thomas Waites, Keith David and A Wilford Brimley. - ‘The Thing: 27,000 Hours’ (6:01), with optional commentary. This short film was made by Sean Hogan for exhibition at London Frightfest in 2011, part of a series of six short films intended to pay tribute to Carpenter’s pictures. - ‘Fans of The Thing’: - -- ‘Outpost #31: History and Impact of the Fans’ (15:42). Todd Cameron, who developed the website Outpost #31 to pay homage to The Thing, discusses the origins of Outpost #31 and his intentions for its future. - -- ‘“We’ve Found Something in the Ice”: A Fan’s Journey’ (5:38). A fan of the film, Peter Abbott, visited the film’s locations in 2016, and is interviewed here about his experiences.  - -- ‘The Thing Tribute Artwork by Danny Wagner’ (0:24). In this stills gallery, special effects artist Danny Wagner shares some tribute pieces he has made in honour of The Thing. - -- ‘The Thing Tribute Artwork by Danny Wagner’ (0:24). In this stills gallery, special effects artist Danny Wagner shares some tribute pieces he has made in honour of The Thing.

- Trailer (1:58). - Production Archive - -- Production Background Archive (0:29). - -- Cast Production Photographs (0:15). - -- Production Art and Storyboards (0:52). - -- Location Design (1:08). - -- Production Archives (1:01). - -- The Saucer: Frame By Frame (0:47); Full Motion (2:22). - -- The Blairmonster: Frame By Frame (0:44); Full Motion (1:00). - -- Outtakes: Frame By Frame (0:07); Full Motion (4:08). - -- Post Production (0:28).

Overall

It’s always difficult to write about favourite films, and The Thing has long been one of my favourites – ever since I first encountered it via its UK television premiere, a late-night broadcast on ITV one Saturday evening, the film surprisingly intact other than the removal of a couple of the more ‘fruity’ lines of dialogue (Palmer’s line ‘You’ve got to be fucking kidding’ and Garry’s assertion that ‘I’d rather not spend the rest of this winter tied to this fucking couch!’). Suffice to say, it was poorly received on its initial release, its downbeat tone and ambiguous ending standing in relief against the dominant paradigms of the burgeoning post-Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)/post-Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) New Hollywood movement and feeling more like a throwback to American films of the 1970s. However, Carpenter’s picture has an ardent fan following, and in the years since its release its positive qualities have come to be recognised more widely. Certainly, it’s both a visceral and intellectual piece of filmmaking, sitting comfortably alongside other 1980s pictures like Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987) and Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), all of which felt deeply subversive in the ways in which they appropriated Hollywood paradigms and employed them in the service of a more challenging, provocative and often satirical engagement with the issues of the day. It’s always difficult to write about favourite films, and The Thing has long been one of my favourites – ever since I first encountered it via its UK television premiere, a late-night broadcast on ITV one Saturday evening, the film surprisingly intact other than the removal of a couple of the more ‘fruity’ lines of dialogue (Palmer’s line ‘You’ve got to be fucking kidding’ and Garry’s assertion that ‘I’d rather not spend the rest of this winter tied to this fucking couch!’). Suffice to say, it was poorly received on its initial release, its downbeat tone and ambiguous ending standing in relief against the dominant paradigms of the burgeoning post-Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)/post-Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) New Hollywood movement and feeling more like a throwback to American films of the 1970s. However, Carpenter’s picture has an ardent fan following, and in the years since its release its positive qualities have come to be recognised more widely. Certainly, it’s both a visceral and intellectual piece of filmmaking, sitting comfortably alongside other 1980s pictures like Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987) and Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), all of which felt deeply subversive in the ways in which they appropriated Hollywood paradigms and employed them in the service of a more challenging, provocative and often satirical engagement with the issues of the day.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release is deeply impressive, improving hugely on the previously available home video versions of this picture, including the US Blu-ray release from Shout! (which, based on a 2k scan of an interpositive source, has an artificially ‘sharp’ appearance and also has issues with fringing/bleeding within the palette). Shout!’s US release contains an exclusive commentary track by Dean Cundey, on the other hand, but Arrow’s new UK Blu-ray disc contains an extraordinary array of contextual material nevertheless – both old (‘Terror Takes Shape’) and new. It’s an incredible release of an amazing film; with the qualifier that this has been one of my favourite films for over 30 years now, I feel confident in asserting that this is easily one of the best releases of the year and offers an essential package for fans of Carpenter’s picture. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release is deeply impressive, improving hugely on the previously available home video versions of this picture, including the US Blu-ray release from Shout! (which, based on a 2k scan of an interpositive source, has an artificially ‘sharp’ appearance and also has issues with fringing/bleeding within the palette). Shout!’s US release contains an exclusive commentary track by Dean Cundey, on the other hand, but Arrow’s new UK Blu-ray disc contains an extraordinary array of contextual material nevertheless – both old (‘Terror Takes Shape’) and new. It’s an incredible release of an amazing film; with the qualifier that this has been one of my favourite films for over 30 years now, I feel confident in asserting that this is easily one of the best releases of the year and offers an essential package for fans of Carpenter’s picture.

References: Billson, Anne, 1997: BFI Modern Classics: ‘The Thing’. London: British Film Institute Conolly, Jez, 2013: Devil’s Advocates: ‘The Thing’. Leighton Buzzard: Auteur Donovan, Barna William, 2011: Conspiracy Films: A Tour of Dark Places in the American Conscious. London: McFarland and Company Hemphill, Jim, 2015: ‘The Thing: A Q&A with Dean Cundey, ASC, about his work on John Carpenter’s The Thing’. [Online.] The American Society of Cinematographers https://www.theasc.com/ac_magazine/May2015/TheThing/page1.php Date accessed: 12 November, 2015 Mulvey-Roberts, Marie, 2004: ‘“A Spook Ride on Film”: Carpenter and the Gothic’. In: Conrich, Ian & Woods, David (eds), 2004: The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror. London: Wallflower Press: 78-106

|

|||||

|