|

|

Miracle Mile (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th November 2017). |

|

The Film

Miracle Mile (Steve De Jarnatt, 1988) Miracle Mile (Steve De Jarnatt, 1988)

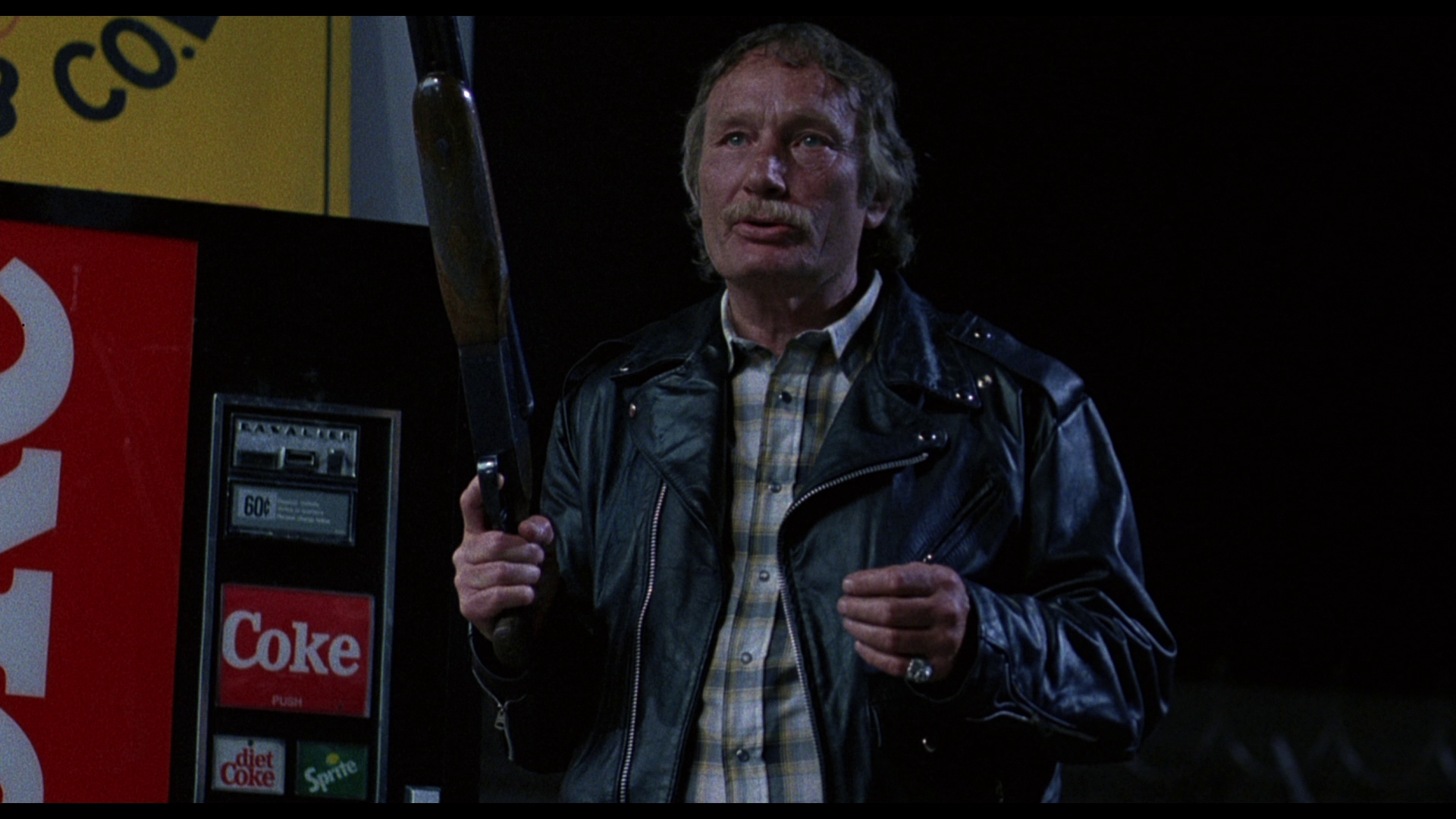

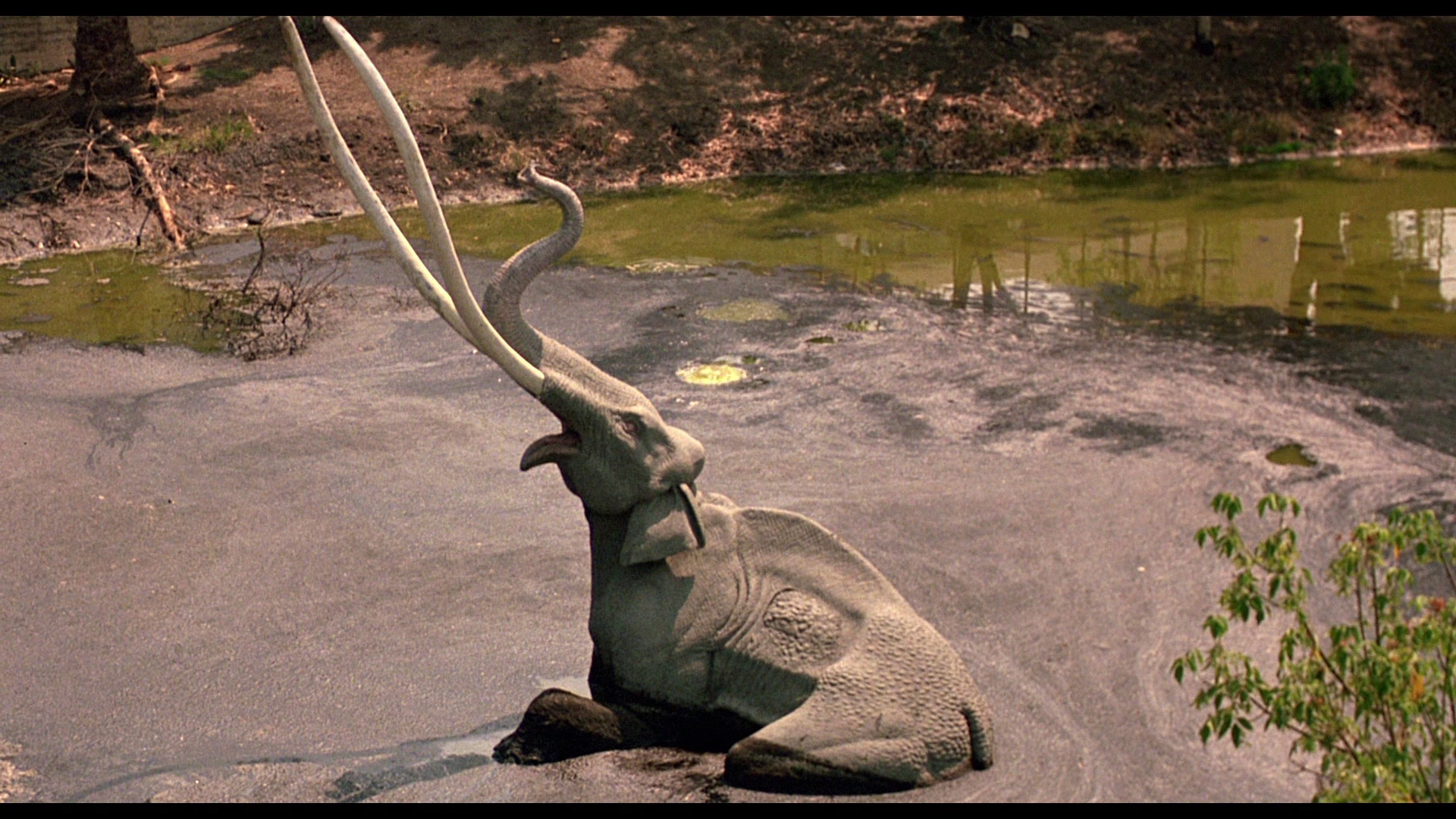

At the La Brea Tar Pits, thirty year old jazz trombonist Harry Washello (Anthony Edwards) meets Julie Peters (Mare Winningham), and the pair fall in love immediately. After meeting Julie’s grandfather Ivan (John Agar) and his estranged wife, Julie’s grandmother Lucy (Lou Hancock), Harry retires to his hotel for a ‘granny nap’ but vows to meet Julie at 12h15, close to Johnie’s Coffee Shop. However, a freak incident in the hotel (involving a bird’s nest which catches fire) results in the building’s electricity shutting down; Harry’s alarm doesn’t sound and he oversleeps, missing his date with Julie. Harry arrives at Johnie’s Coffee Shop at 04h00, but Julie isn’t there: she’s already returned to the apartment in which she lives with Lucy. Harry calls Lucy’s apartment on the payphone outside the coffee shop, then retreats inside and seats himself among the eccentrics who inhabit the coffee shop at night. Hearing the payphone outside ringing and assuming it’s Julie calling him back, Harry answers the call. A desperate young man is on the other end of the line, and having dialled the wrong number he mistakes Harry for his father, warning Harry that the US is preparing a pre-emptive nuclear strike in 50 minutes, which will result in a response in kind within the next hour and a half. Nuclear annihilation imminent, Harry warns the inhabitants of Johnie’s. One of the patrons, a businesswoman named Landa (Denise Crosby) calls a friend in the government via her mobile telephone, and the information she receives seems to confirm what Harry was told. Landa arranges an aeroplane to transpot Johnie’s patrons out of the blast zone, and Johnie’s cook Fred (Robert DoQui) loads a truck with supplies. The patrons of Johnie’s pile into the truck, which Fred directs towards the airport. However, Harry leaps from the truck with the intention of heading towards Julie’s apartment at Park La Brea and convincing Julie to leave the city with him.  Using a revolver stolen from Fred, Harry hijacks a car being driven by a young African American man, Wilson (Mykelti Williamson). Wilson is a petty thief and the car is filled with stolen car radios. They stop at a gas station where the attendant (Eddie Bunker) holds a shotgun on them, believing them to be thieves. However, the police arrive; Wilson sprays them with petrol, which ignites, killing the two officers and destroying the gas station. Using a revolver stolen from Fred, Harry hijacks a car being driven by a young African American man, Wilson (Mykelti Williamson). Wilson is a petty thief and the car is filled with stolen car radios. They stop at a gas station where the attendant (Eddie Bunker) holds a shotgun on them, believing them to be thieves. However, the police arrive; Wilson sprays them with petrol, which ignites, killing the two officers and destroying the gas station.

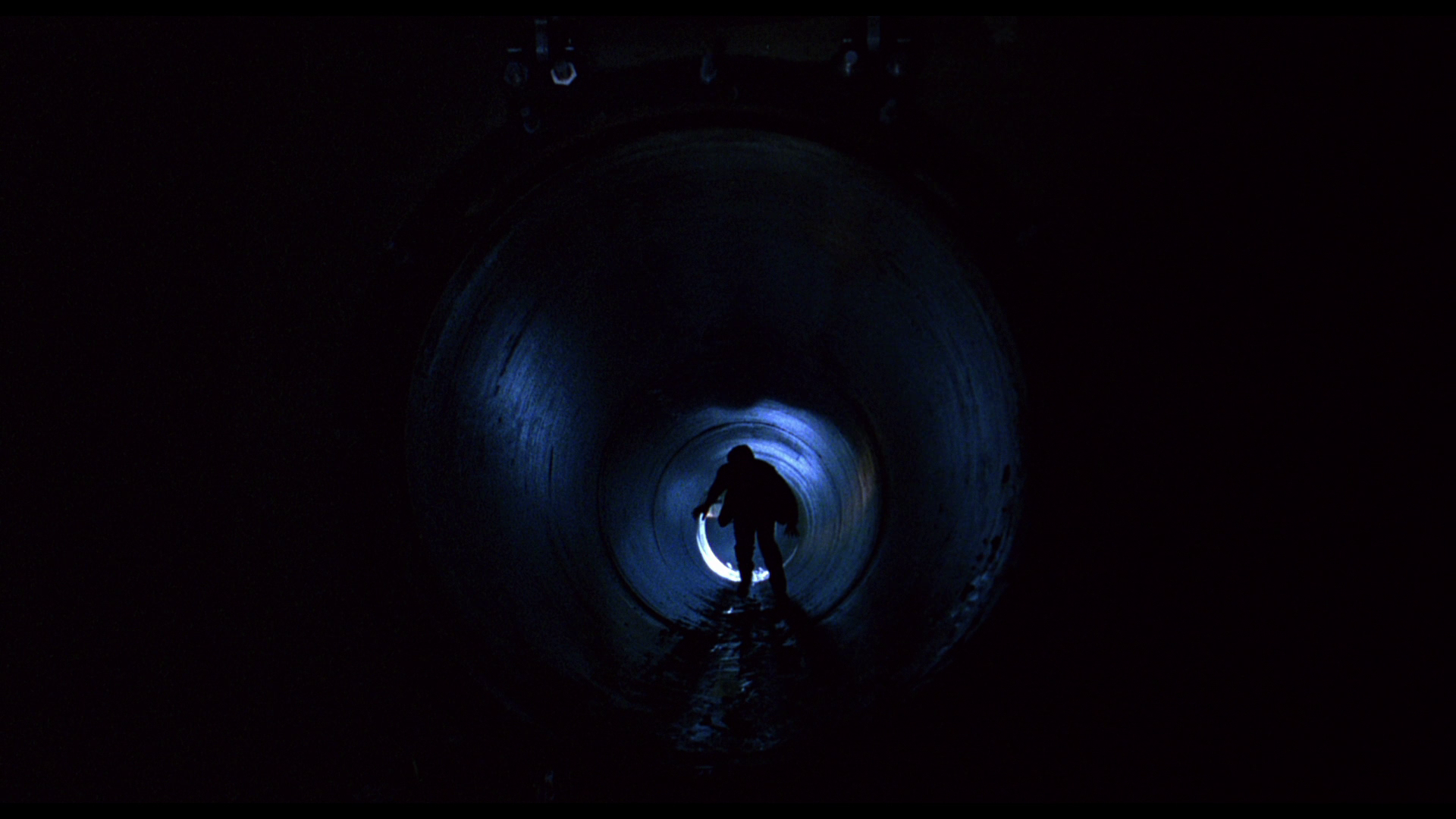

Harry makes it to Julie’s apartment, and together they ascend the Mutual Life building to the helipad at the top, where Landa has arranged transportation to the airport in the form of a helicopter. Landa’s friend from the government is there with spiky CIA agent Gerstead (Kurt Fuller), who doesn’t believe Harry’s story about the pre-emptive nuclear strike. The helicopter is also there, but with no pilot. Harry leaves the Mutual Life building to find a pilot, exploring a 24 hour gym where he encounters a powerlifting Vietnam vet (Brian Thompson) who offers to fly the helicopter out of the city, but only if he can bring along his lover Leslie (Herbert Fair). Julie expresses doubts about Harry’s story, but then the couple see the streets of the city flooded with rioters and looters. Harry and Julie become separated but are eventually reunited, just in time to see three nuclear missiles heading to the city. Establishing its neo-noir credentials from the get-go, Miracle Mile begins with a voiceover narration by Harry which could be taken directly from the pages of a David Goodis novel about a doomed romance: ‘I never really saw the big picture before’, Harry intones, ‘Not till today. Love can sure spin your head around [….] Fate is a funny thing. We must have meant to be together, Julie and I’. With most of the key action taking place during the early hours of the morning, the film takes place in a cityscape drenched in neon – an aesthetic comparable with other neo-noir pictures and noir hybrids of the 1980s such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984), Charles Band’s Trancers (1985) and many of Michael Mann’s films (from 1981’s Thief to Collateral in 2004).  The title of Miracle Mile alludes to the mile-long stretch of Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, where the film’s narrative is set, the picture employing some key locations associated with the area – including the La Brea Tar Pits, where Harry and Julie meet, and the iconic Johnie’s Coffee Shop (a location also used in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, 1992; the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski, 1998; and Tony Kaye’s American History X, also 1998). To some extent, jazz trombonist Harry’s journey across the night-time landscape of Los Angeles allies De Jarnatt’s picture with other 1980s neo-noir pictures in which unlikely protagonists traverse city streets which turn menacing after dark, including Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) and John Landis’ Into the Night (also 1985). Like those pictures, Miracle Mile adopts a picaresque structure and sharp shifts in tone, depicting a nocturnal cityscape populated by eccentrics and miscreants. When Harry jumps from Fred’s truck and hijacks the car driven by Wilson, he discovers that Wilson is a petty thief. When they stop at the gas station and Eddie Bunker’s attendant holds them at gunpoint, they are all united when the police arrive. ‘Holy mother of God, man, they’ll give me five years for this fucking gun’, the attendant declares. ‘They’ll give me ten years for what’s in my trunk’, Wilson adds. The scene shifts jarringly from comedy to horror when, immediately afterwards, Wilson sprays petrol at the police and one of the officers fires their revolver, igniting the petrol and turning the two police officers into flaming effigies. As Harry and Wilson drive away in the stolen police car, the gas station explodes. This scene is arguably the turning point of the picture: with the deaths of the police officers, the viewer becomes aware of just how destructive the panic Harry has caused is, and the extent to which Harry, the film’s sympathetic protagonist, is implicated in the horrific deaths of the two police officers and the gas station attendant. (These jarring shifts in tone are complemented by some language that, given the breezy approach of much of the picture, is strikingly strong: ‘The only reason I’m here is because that cunt [Landa] paid me three grand to do this shit’, Gerstead tells Harry.) The title of Miracle Mile alludes to the mile-long stretch of Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, where the film’s narrative is set, the picture employing some key locations associated with the area – including the La Brea Tar Pits, where Harry and Julie meet, and the iconic Johnie’s Coffee Shop (a location also used in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, 1992; the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski, 1998; and Tony Kaye’s American History X, also 1998). To some extent, jazz trombonist Harry’s journey across the night-time landscape of Los Angeles allies De Jarnatt’s picture with other 1980s neo-noir pictures in which unlikely protagonists traverse city streets which turn menacing after dark, including Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) and John Landis’ Into the Night (also 1985). Like those pictures, Miracle Mile adopts a picaresque structure and sharp shifts in tone, depicting a nocturnal cityscape populated by eccentrics and miscreants. When Harry jumps from Fred’s truck and hijacks the car driven by Wilson, he discovers that Wilson is a petty thief. When they stop at the gas station and Eddie Bunker’s attendant holds them at gunpoint, they are all united when the police arrive. ‘Holy mother of God, man, they’ll give me five years for this fucking gun’, the attendant declares. ‘They’ll give me ten years for what’s in my trunk’, Wilson adds. The scene shifts jarringly from comedy to horror when, immediately afterwards, Wilson sprays petrol at the police and one of the officers fires their revolver, igniting the petrol and turning the two police officers into flaming effigies. As Harry and Wilson drive away in the stolen police car, the gas station explodes. This scene is arguably the turning point of the picture: with the deaths of the police officers, the viewer becomes aware of just how destructive the panic Harry has caused is, and the extent to which Harry, the film’s sympathetic protagonist, is implicated in the horrific deaths of the two police officers and the gas station attendant. (These jarring shifts in tone are complemented by some language that, given the breezy approach of much of the picture, is strikingly strong: ‘The only reason I’m here is because that cunt [Landa] paid me three grand to do this shit’, Gerstead tells Harry.)

De Jarnatt surrounds his principal cast with some impressive secondary roles, including the oddball patrons of Johnie’s Coffee Shop: lecherous Harlan (Claude Earl Jones) and his buddy Mike (Alan Rosenberg), transvestite Roberta (Danny De La Paz), a drunk (played by Earl Boen), a woman masquerading as an airline hostess (Diane Delano), the coffee shop’s cook Fred (Robert DoQui) and waitress (O-Lan Jones, who would essay a similar character in the opening sequence of Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, 1995). Throughout, the film draws a strange and subtle equivalency between the impending consummation of Harry and Julie’s relationship and nuclear annihilation. ‘Third date, Harry, and I’m gonna screw your eyes blue’, Julie tells Harry as Harry retires to his hotel for a nap – before missing his date with Julie. ‘Yep, just your plain, good old-fashioned girl’, Harry quips. Later, after Harry has missed his date with Julie and answers the payphone outside Johnie’s, the young man on the other end of the line describes the impending nuclear pre-emptive strike using words which connect it with the sex act: ‘We shoot our wad in 50 minutes’, he cries. Harry repeats these words to various characters later in the film. Finally, after seeing various people fucking in the street as a response to their impending nuclear annihilation, Harry and Julie seem about to consummate their relationship in the elevator as it carries them up to the helipad atop the Mutual Life building; they kiss passionately, removing their outer garments but are interrupted when the elevator reaches the helipad and the doors open to reveal Gerstead, high and stripped to the waist, and the sight of nuclear missiles flying over the Hollywood sign: the ‘wad’, it seems, has been ‘shot’. De Jarnatt surrounds his principal cast with some impressive secondary roles, including the oddball patrons of Johnie’s Coffee Shop: lecherous Harlan (Claude Earl Jones) and his buddy Mike (Alan Rosenberg), transvestite Roberta (Danny De La Paz), a drunk (played by Earl Boen), a woman masquerading as an airline hostess (Diane Delano), the coffee shop’s cook Fred (Robert DoQui) and waitress (O-Lan Jones, who would essay a similar character in the opening sequence of Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, 1995). Throughout, the film draws a strange and subtle equivalency between the impending consummation of Harry and Julie’s relationship and nuclear annihilation. ‘Third date, Harry, and I’m gonna screw your eyes blue’, Julie tells Harry as Harry retires to his hotel for a nap – before missing his date with Julie. ‘Yep, just your plain, good old-fashioned girl’, Harry quips. Later, after Harry has missed his date with Julie and answers the payphone outside Johnie’s, the young man on the other end of the line describes the impending nuclear pre-emptive strike using words which connect it with the sex act: ‘We shoot our wad in 50 minutes’, he cries. Harry repeats these words to various characters later in the film. Finally, after seeing various people fucking in the street as a response to their impending nuclear annihilation, Harry and Julie seem about to consummate their relationship in the elevator as it carries them up to the helipad atop the Mutual Life building; they kiss passionately, removing their outer garments but are interrupted when the elevator reaches the helipad and the doors open to reveal Gerstead, high and stripped to the waist, and the sight of nuclear missiles flying over the Hollywood sign: the ‘wad’, it seems, has been ‘shot’.

Director Steve De Jarnatt’s previous picture, his feature film debut, had been Cherry 2000 (1987, released recently on Blu-ray by Signal One Entertainment and reviewed by us here). A sci-fi reworking of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, Cherry 2000 had been written by Michael Almereyda, who would make his own directorial debut with Twister in 1988, and De Jarnatt asserted that on that specific project he was little more than ‘a late fill-in for a director who’d left the project’ (De Jarnatt, quoted in Chaw, 2012: 177). Miracle Mile had been written by De Jarnatt himself, the script being completed in 1979; at that time, the film seemed to be heading into production by Warner Brothers, but the project stalled, and in 1983 American Film cited it as one of the ten most impressive unproduced screenplays circulating in Hollywood. De Jarnatt eventually bought the script back from Warner Brothers, fearing that the studio would interfere with his material and, in particular, change the ending (Oberhaus, 2017: np). After De Jarnatt had rewritten the script, Warner Brothers offered him almost half a million dollars for it, but De Jarnatt turned the studio down, commenting in an interview with Daniel Oberhaus that ‘I think if I would've taken the money, the film would've never been made or it would've been turned into a bad version of the Twilight Zone’ (De Jarnatt, quoted in ibid.). Eventually, De Jarnatt found in John Daly’s company Hemdale a studio sympathetic to his vision for the project, and Hemdale funded the picture for $3.7 million (ibid.). Director Steve De Jarnatt’s previous picture, his feature film debut, had been Cherry 2000 (1987, released recently on Blu-ray by Signal One Entertainment and reviewed by us here). A sci-fi reworking of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, Cherry 2000 had been written by Michael Almereyda, who would make his own directorial debut with Twister in 1988, and De Jarnatt asserted that on that specific project he was little more than ‘a late fill-in for a director who’d left the project’ (De Jarnatt, quoted in Chaw, 2012: 177). Miracle Mile had been written by De Jarnatt himself, the script being completed in 1979; at that time, the film seemed to be heading into production by Warner Brothers, but the project stalled, and in 1983 American Film cited it as one of the ten most impressive unproduced screenplays circulating in Hollywood. De Jarnatt eventually bought the script back from Warner Brothers, fearing that the studio would interfere with his material and, in particular, change the ending (Oberhaus, 2017: np). After De Jarnatt had rewritten the script, Warner Brothers offered him almost half a million dollars for it, but De Jarnatt turned the studio down, commenting in an interview with Daniel Oberhaus that ‘I think if I would've taken the money, the film would've never been made or it would've been turned into a bad version of the Twilight Zone’ (De Jarnatt, quoted in ibid.). Eventually, De Jarnatt found in John Daly’s company Hemdale a studio sympathetic to his vision for the project, and Hemdale funded the picture for $3.7 million (ibid.).

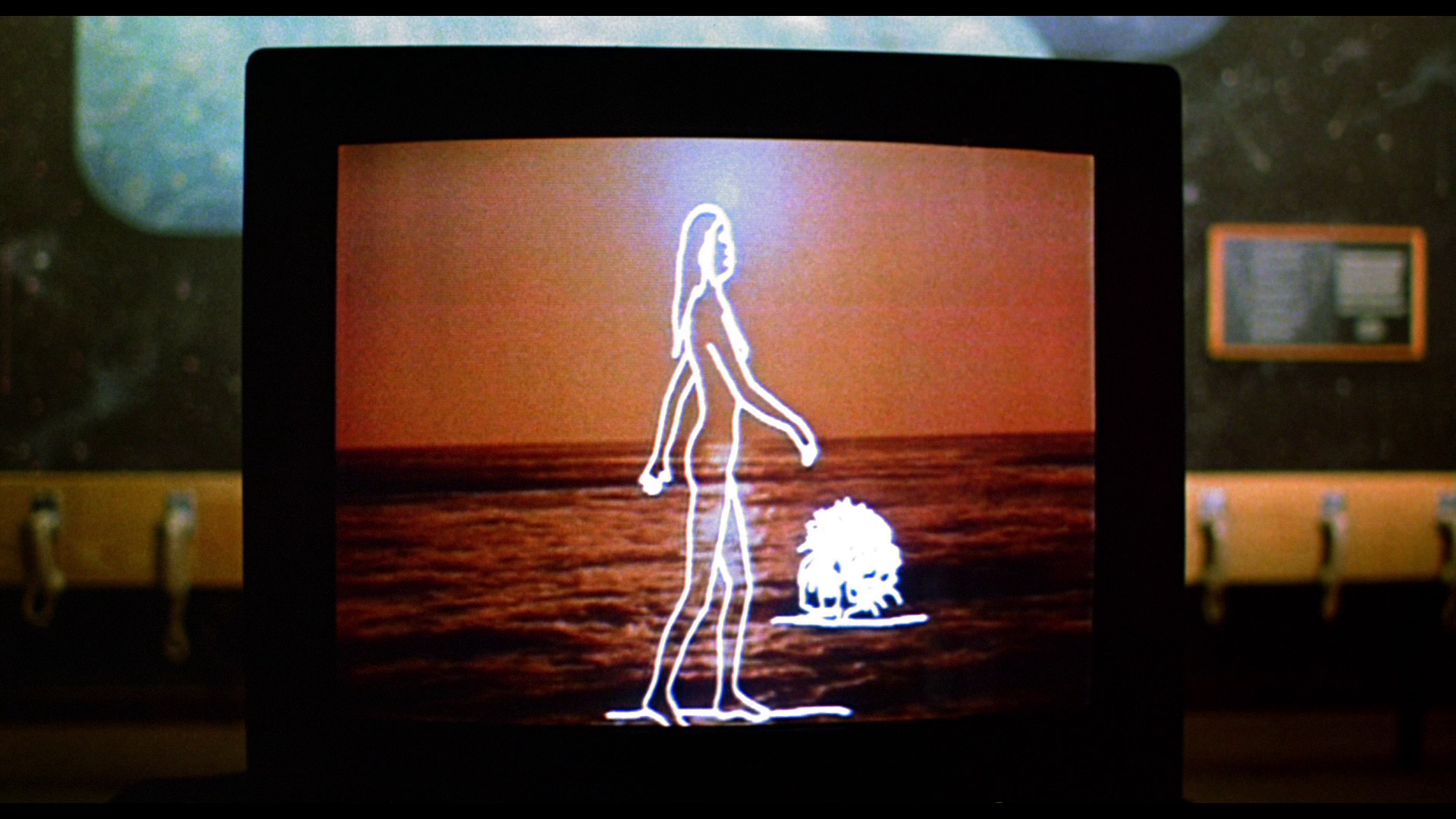

In his monograph on Miracle Mile, Walter Chaw suggests De Jarnatt’s picture has some similarities with John Carpenter’s roughly contemporaneous They Live (1988): both films are, Chaw argues, concerned with ‘stripping away illusion and of waking the sleeping’ (Chaw, 2012: 4). When Harry receives the telephone call from the desperate young man who tells Harry of the impending nuclear strike, the call ends with Harry listening as gunshots ring out on the other end of the line and a different male voice tells Harry, ‘Forget everything you’ve just heard and go back to sleep’. Like They Live, Miracle Mile features, and foregrounds, many mediated images. The film’s opening titles play out over a video screen on which the Big Bang is explained via a disembodied voiceover and through onscreen animation (rather like the explanation of how the dinosaurs were re/created in Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, 1993). We see the horizontal lines of resolution, and the viewer is disoriented, at least for a moment, in seeing these visual indices of television during a motion picture shot on 35mm film; that is, until the camera pulls back to reveal that the images are playing on a television monitor within the museum at the La Brea Tar Pits where Harry meets Julie for the first time. Harry’s awareness of the impending nuclear holocaust is prompted when he intercepts a telephone call meant for someone else (another mediated message), and the theme resurfaces at the climax of the film when Harry and Julie find the city streets swamped with looters. Harry stands in front of the display window of an electrical goods store as, on the television monitors inside, a news broadcast warns of the nuclear strike. Harry smashes the glass of the window so that he can hear what the newscaster is saying, and the programme cuts to an outside broadcast which is interrupted when the news crew are shot at and killed, the camera falling to the floor – an action which punctures the perceived omniscience of television journalism. In his monograph on Miracle Mile, Walter Chaw suggests De Jarnatt’s picture has some similarities with John Carpenter’s roughly contemporaneous They Live (1988): both films are, Chaw argues, concerned with ‘stripping away illusion and of waking the sleeping’ (Chaw, 2012: 4). When Harry receives the telephone call from the desperate young man who tells Harry of the impending nuclear strike, the call ends with Harry listening as gunshots ring out on the other end of the line and a different male voice tells Harry, ‘Forget everything you’ve just heard and go back to sleep’. Like They Live, Miracle Mile features, and foregrounds, many mediated images. The film’s opening titles play out over a video screen on which the Big Bang is explained via a disembodied voiceover and through onscreen animation (rather like the explanation of how the dinosaurs were re/created in Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, 1993). We see the horizontal lines of resolution, and the viewer is disoriented, at least for a moment, in seeing these visual indices of television during a motion picture shot on 35mm film; that is, until the camera pulls back to reveal that the images are playing on a television monitor within the museum at the La Brea Tar Pits where Harry meets Julie for the first time. Harry’s awareness of the impending nuclear holocaust is prompted when he intercepts a telephone call meant for someone else (another mediated message), and the theme resurfaces at the climax of the film when Harry and Julie find the city streets swamped with looters. Harry stands in front of the display window of an electrical goods store as, on the television monitors inside, a news broadcast warns of the nuclear strike. Harry smashes the glass of the window so that he can hear what the newscaster is saying, and the programme cuts to an outside broadcast which is interrupted when the news crew are shot at and killed, the camera falling to the floor – an action which punctures the perceived omniscience of television journalism.

Video

The film is uncut, with a running time of 88:03 mins. Presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. With richly-textured mise-en-scène, Miracle Mile was slickly photographed by Theo van de Sande. Complicated camera setups are employed (eg, complex tracking shots) and there is some great ‘golden hour’ photography in the opening sequences whilst during the night-time scenes, the screen is bathed in pastels and primary colours (reds and blues, for example). The film is uncut, with a running time of 88:03 mins. Presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 22Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. With richly-textured mise-en-scène, Miracle Mile was slickly photographed by Theo van de Sande. Complicated camera setups are employed (eg, complex tracking shots) and there is some great ‘golden hour’ photography in the opening sequences whilst during the night-time scenes, the screen is bathed in pastels and primary colours (reds and blues, for example).

The presentation is very good. Some damage is present in the form of black fleck and specks which suggest that a positive source was used for the presentation. Skintones are natural, whilst the pastels and primary colours shine through vigorously. Contrast levels are nicely-balanced, with rich and defined midtones, deep shadows and even highlights. Finally, a solid encode ensures the picture retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is clean and clear throughout, evidencing good range and showcasing Tangerine Dream’s ethereal score very well. The track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing; these are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by director Steve De Jarnatt. This commentary is moderated by Walter Chaw, whose monograph about Miracle Mile is cited in the main body of this review above. Chaw and De Jarnatt offer a lively and insightful discussion of the film, De Jarnatt foregrounding the theme of mediated information also discussed above (and drawing out its relevance for today’s climate of discourse about ‘fake news’). It’s an excellent track which highlights the trials and tribulations of working on the fringes of the Hollywood system, offering insight into the craft of filmmaking and exploring the film’s themes. - An audio commentary by De Jarnatt, cinematographer Theo van de Sande and production designer Chris Horner. This is another fascinating commentary track which is a little more technical than the other track, Theo van de Sande in particular delivering some clear and fascinating reflections on the picture’s photography, suggesting that the production aimed for ‘crystalline’ photography – a hard and unsentimental aesthetic that was achieved via precise manipulation of lighting during the night-time scenes and the choice of different film stocks for the day and night footage. - ‘Last Orders at Johnie’s’ (30:43). In a new interview, De Jarnatt talks about his career in films and television, discussing his 1978 film noir-esque student short film ‘Tarzana’, which features Timothy Carey and Eddie Constantine. (Some tantalising footage of ‘Tarzana’ is included, and though early information suggested the short would be included in this release of Miracle Mile, frustratingly that’s not so – presumably because of the reputedly complicated rights issues that have plagued ‘Tarzana’.) He discusses the origins and production of Miracle Mile and talks about the differences between the finished picture and the original script. De Jarnatt is a witty interviewee, and the interview offers some fascinating information about both De Jarnatt’s career and Miracle Mile specifically.

- ‘Harry & Julie’ (12:25). In a recent interview, which was recorded for inclusion on the US release of the picture from Kino Lorber, Anthony Edwards and Mare Winningham reflect on their involvement in Miracle Mile and talk about their roles in the film. - ‘Reunion at Johnie’s Diner’ (24:41). De Jarnatt and the supporting cast – the actors who play the eccentric patrons of Johnie’s – and crew are reunited in Johnie’s Coffee Shop and discuss their careers. The participants are warm and friendly throughout, and this is an entertaining featurette. - ‘The Music of Tangerine Dream’ (16:37). Paul Haslinger, who was in Tangerine Dream from 1986 to 1990, discusses the film’s music and Tangerine Dream’s approach to scoring the picture. - ‘Excavations from the Editing Room’ (11:20). This ‘extra’ comprises videotape dailies from the picture, featuring additional footage from a number of sequences – many just additional shots or extensions to shots. - Alternate Ending (0:56). This ‘additional ending’ is very brief and adds only a moment or two to the film’s moment of resolution. It’s arguably twee and unnecessary, and the ending of the completed film is much more impactful. - Storyboard to Film Comparisons (1:54). Some of the storyboards are presented alongside timecoded footage from the production. - ‘Rubiaux Rising’ (21:43). De Jarnatt reads ‘Rubiaux Rising’, an impactful short story that was included in the volume The Best American Short Stories 2009. The story focuses on a Gulf War veteran who becomes trapped in an attic during Hurrican Katrina. It’s an excellent piece, read well by its author. - The film’s trailer (2:15).

Overall

Miracle Mile is a film very much of its time, its fusion of romance, neo-noir and nuclear holocaust seeming very much of the 1980s whilst its themes (a world teetering on the brink of destruction, the unreliability of mediated information) feeling strikingly relevant to today. Personally, I had only previously seen the film via its 1991 UK VHS release, and by contrast this Blu-ray release is a revelation. The film’s photography is particularly impressive, the combination of van de Sande’s icy visuals and Tangerine Dream’s score being reminiscent of Michael Mann’s Thief, in particular. Watching Arrow’s new Blu-ray release has certainly contributed to my already high esteem for the film. It’s an impressive, somewhat haunting picture though, admittedly, its oddball shifts in tone may alienate some viewers and mark it as a ‘cult’ film. The ending is brave and avoids any kind of sop to Hollywood conventions that, as De Jarnatt has often suggested, would have ensued had the picture been pushed into production by Warner Brothers. It’s a shame that De Jarnatt has directed so few feature films, with most of his later work being in television (including a number of episodes of the medical drama E.R., which featured Anthony Edwards among its core cast). Miracle Mile is a film very much of its time, its fusion of romance, neo-noir and nuclear holocaust seeming very much of the 1980s whilst its themes (a world teetering on the brink of destruction, the unreliability of mediated information) feeling strikingly relevant to today. Personally, I had only previously seen the film via its 1991 UK VHS release, and by contrast this Blu-ray release is a revelation. The film’s photography is particularly impressive, the combination of van de Sande’s icy visuals and Tangerine Dream’s score being reminiscent of Michael Mann’s Thief, in particular. Watching Arrow’s new Blu-ray release has certainly contributed to my already high esteem for the film. It’s an impressive, somewhat haunting picture though, admittedly, its oddball shifts in tone may alienate some viewers and mark it as a ‘cult’ film. The ending is brave and avoids any kind of sop to Hollywood conventions that, as De Jarnatt has often suggested, would have ensued had the picture been pushed into production by Warner Brothers. It’s a shame that De Jarnatt has directed so few feature films, with most of his later work being in television (including a number of episodes of the medical drama E.R., which featured Anthony Edwards among its core cast).

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a very pleasing presentation of the main feature, offering a tighter and more consistent encode than the US release from Kino Lorber alongside a wider array of contextual material. It’s a shame that ‘Tarzana’ isn’t included, and the glimpses of the short offered in the interview with De Jarnatt are tantalizing, but it would seem this short film is held up by complicated rights-related issues. Certainly, regardless of that fact, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Miracle Mile offers a presentation that the film deserves and a very pleasing selection of extra features. References: Chaw, Walter, 2012: Miracle Mile. Lulu.com Oberhaus, Daniel, 2017: ‘This Cult 80s Film About the Nuclear Apocalypse Is Still Relevant, and That Sucks’. [Online.] https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/wjeyq4/miracle-mile

|

|||||

|