|

|

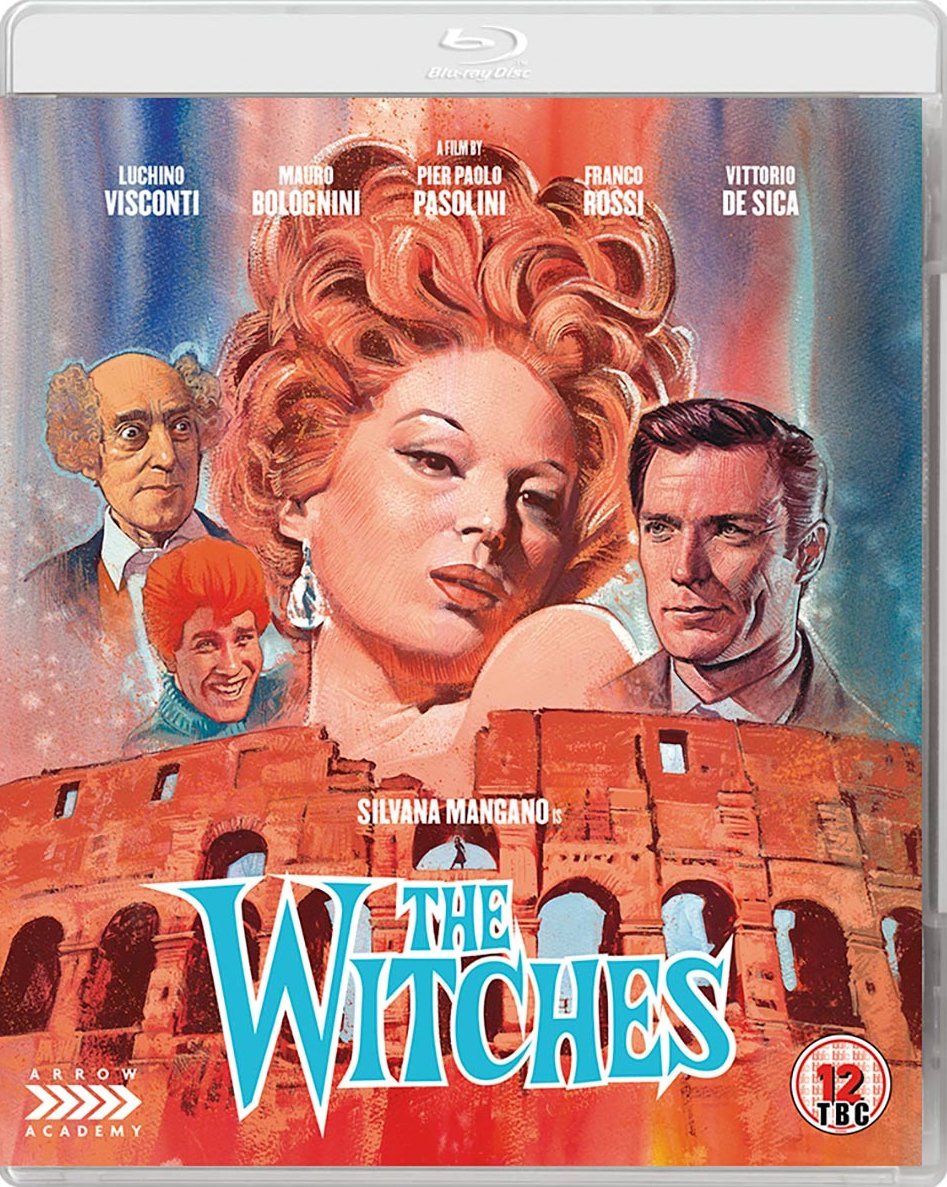

Witches (The) AKA Le streghe AKA Les sorcières (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th February 2018). |

|

The Film

Le streghe (The Witches: Luchino Visconti, Mauro Bolognini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Franco Rossi & Vittorio De Sica, 1967) A portmanteau film with each of its segments directed by some of Italy’s key filmmakers, the stories in Le streghe are linked by the presence of Silvano Mangano, the then-wife of the film’s producer, Dino De Laurentiis. De Laurentiis reputedly financed the picture in order to revive Mangano’s career as a screen actor, the segments filmed under disparate conditions. Each story stars Mangano as a different stereotype/archetype of femininity.  The film opens within a segment directed by Luchino Visconti, ‘La strega bruciata’ (‘The Witch Burned Alive’), in which Mangano essays the role of Gloria, a jet-setting starlet who finds herself deeply alienated from her own humanity, her vulnerabilities concealed by layers of makeup and modish clothes. Gloria arrives at an alpine chalet where her friend Valeria (Annie Girardot) is throwing a party to celebrate her tenth anniversary. But there’s little to celebrate: Valeria’s marriage is stifling and sexless, her husband Paolo disinterested in her. The film opens within a segment directed by Luchino Visconti, ‘La strega bruciata’ (‘The Witch Burned Alive’), in which Mangano essays the role of Gloria, a jet-setting starlet who finds herself deeply alienated from her own humanity, her vulnerabilities concealed by layers of makeup and modish clothes. Gloria arrives at an alpine chalet where her friend Valeria (Annie Girardot) is throwing a party to celebrate her tenth anniversary. But there’s little to celebrate: Valeria’s marriage is stifling and sexless, her husband Paolo disinterested in her.

Gloria is initially greeted with enthusiasm by the other partygoers, but when she faints after dancing for them, her jealous and catty peers gradually strip away her makeup and accoutrements, leaving her ‘nude’ and without her ‘mask’. At night, Gloria wanders into the library where Valeria’s husband flirts with her. Gloria discovers she is pregnant and calls her husband in New York, film producer Antonio (a photograph of ‘Antonio’ in fact depicts Mangano’s real-life husband, the film’s producer Dino De Laurentiis), to tell him the news. However, Antonio is disinterested and wants Gloria to continue taking acting roles, suggesting that she should have an abortion in order to ensure continuance in her career. In the morning, the paparazzi storm the chalet, and an entourage replaces Gloria’s ‘mask’, painting her face with makeup and dressing her in her expensive, modish clothes once again, before she is carried away in a helicopter. ‘The Witch Burned Alive’ is a story that depicts celebrity as a form of trap, something that alienates the individual from both their loved ones and their humanity. Gloria is envied by her peers: ‘Every woman wants to look like you’, Valeria tells her upon her arrival at the chalet, ‘Unfortunately, we’re all just poor imitation Glorias’. Her peers – Valeria’s friends – have bizarre, snobbish attitudes and class-based prejudices. (It wouldn’t be a Visconti picture without these, of course.) One of the guests at Valeria’s party tells Gloria, ‘There’s nothing the matter with being a pauper or being a prince. It’s the in-between that’s disgusting: the middle-class’.  As a celebrity, Gloria is likened to a product or brand: a male guest tells her, ‘You’re a product, a sublime product magnificently tailored to the marked. And the product is the basis of all industry, and thus society’. The guest continues, comparing Gloria to the canned meat that his own company produces. ‘The fact is that you artists are curious specimens, precarious investments’, he says, ‘With a case of laryngitis or a love affair, you’re finished. Everything goes up in smoke’. Gloria cannot be herself for fear of queering the pitch. Being a celebrity requires one to wear a disguise that shields oneself from the prying eyes, and cameras, of the paparazzi. Those around Gloria, even those who profess themselves to be her friends, manipulate her and wish to knock her from her pedestal. When Gloria faints at the party, the other guests gather round and eagerly pluck away those things which make her beautiful. ‘My God’, one of the women says upon seeing Gloria sheered of her jewellery and makeup, ‘she’s like a rat fished out of water’. As a celebrity, Gloria is likened to a product or brand: a male guest tells her, ‘You’re a product, a sublime product magnificently tailored to the marked. And the product is the basis of all industry, and thus society’. The guest continues, comparing Gloria to the canned meat that his own company produces. ‘The fact is that you artists are curious specimens, precarious investments’, he says, ‘With a case of laryngitis or a love affair, you’re finished. Everything goes up in smoke’. Gloria cannot be herself for fear of queering the pitch. Being a celebrity requires one to wear a disguise that shields oneself from the prying eyes, and cameras, of the paparazzi. Those around Gloria, even those who profess themselves to be her friends, manipulate her and wish to knock her from her pedestal. When Gloria faints at the party, the other guests gather round and eagerly pluck away those things which make her beautiful. ‘My God’, one of the women says upon seeing Gloria sheered of her jewellery and makeup, ‘she’s like a rat fished out of water’.

Later that night, a middle-aged female guest demonstrates the alchemical appeal of celebrity by approaching a young houseboy (Helmut Berger) whilst holding a photographic portrait of Gloria in front of her own face; the mismatched pair then kiss passionately. During the same evening, Gloria plays a parlour game with Paolo, in which Paolo suggests that sex is a cure for the headache she is experiencing. ‘You mean I should take a lover like a pill?’, she asks disbelievingly, reminding Paolo that he’s married. ‘Honesty is ineffective, my dear’, Paolo tells her, ‘and quite outmoded. Its only place is in parlour games’. When Gloria doesn’t respond to his advances in the way that he expected, Paolo becomes angry: ‘Get off the set, Gloria. The scene doesn’t stop when you leave the room’, he says, adding ‘You want fame, money, love, and on top of all that you want us to think you’re a good girl’. Gloria is ultimately a tragic figure, unable to connect with her own life and finding herself placed upon a pedestal off which her peers are desperate to knock her.  With the brief segment ‘Senso civico’ (‘Civic Duty’), director Mauro Bolognini offers a darkly comic fable which begins with a car accident that leaves a man (Alberto Sordi) quite badly injured. The man must be taken to the hospital; a female motorist (Mangano) offers to drive him there. She drives at speed, as the man rambles incessantly in a manner which suggests concussion. The injured man realises that the motorist isn’t taking him to the hospital at all but seems to be driving him out of the city. Eventually, reaching her destination she drops the injured man off and, bewildered, he stumbles across a busy road as she walks away to meet her date: she has simply used the injured man as a pretext allowing her to break the speed limit in order to make her date. She wanders off with her lover whilst the injured man staggers into a field and collapses. ‘Civic Duty’ is a very short segment that ends on a darkly ironic punchline. With the brief segment ‘Senso civico’ (‘Civic Duty’), director Mauro Bolognini offers a darkly comic fable which begins with a car accident that leaves a man (Alberto Sordi) quite badly injured. The man must be taken to the hospital; a female motorist (Mangano) offers to drive him there. She drives at speed, as the man rambles incessantly in a manner which suggests concussion. The injured man realises that the motorist isn’t taking him to the hospital at all but seems to be driving him out of the city. Eventually, reaching her destination she drops the injured man off and, bewildered, he stumbles across a busy road as she walks away to meet her date: she has simply used the injured man as a pretext allowing her to break the speed limit in order to make her date. She wanders off with her lover whilst the injured man staggers into a field and collapses. ‘Civic Duty’ is a very short segment that ends on a darkly ironic punchline.

Pasolini’s segment, ‘La terra vista dalla luna’ (‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’) stars Mangano alongside Totò and Ninetto Davoli. Ninetto had been something of a muse for Pasolini, and the director cast Ninetto alongside comic actor Totò as father and son in the 1966 film Uccellacci e uccellini (The Hawks and the Sparrows, 1966). Part of a deal Pasolini made with producer Dino De Laurentiis to produce two shorts for inclusion in future portmanteau pictures, ‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’ was shot soon after The Hawks and the Sparrows, alongside another short, ‘Che cosa sono le nuvole?’ (‘What are the Clouds?’); both stories featured Ninetto and Totò in similar roles, and these three narratives should be seen as part of the same project. ‘What are the Clouds?’ was released as part of the anthology film Capriccio all’italiana (Caprice Italian-Style, 1968). Pasolini’s segment, ‘La terra vista dalla luna’ (‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’) stars Mangano alongside Totò and Ninetto Davoli. Ninetto had been something of a muse for Pasolini, and the director cast Ninetto alongside comic actor Totò as father and son in the 1966 film Uccellacci e uccellini (The Hawks and the Sparrows, 1966). Part of a deal Pasolini made with producer Dino De Laurentiis to produce two shorts for inclusion in future portmanteau pictures, ‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’ was shot soon after The Hawks and the Sparrows, alongside another short, ‘Che cosa sono le nuvole?’ (‘What are the Clouds?’); both stories featured Ninetto and Totò in similar roles, and these three narratives should be seen as part of the same project. ‘What are the Clouds?’ was released as part of the anthology film Capriccio all’italiana (Caprice Italian-Style, 1968).

In ‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’, Totò and Ninetto play father and son, respectively. Totò plays Ciancicato Miao and Ninetto plays his son Basciu. They are first seen at a cemetery mourning the passing of Ciancicato’s wife Christantema. Totò vows to find Ninetto another mother, and on their way home they spot a woman in mourning clothes. ‘Our first victim’, Ciancicato observes, ‘Be respectful, Basciu: she’s some dead man’s wife’. Cinacicato approaches the woman, but she angrily chases him away. The pair see another woman outside the cemetery and approach her before discovering she is a prostitute. Another prospective candidate is spotted, and father and son near her only to realise that she is in fact a mannequin. A year later, Ciancicato and Basciu find a young woman, Absurdity Cai (Mangano) at a roadside shrine. Discovering that Absurdity is deaf and mute, Ciancicato vows to make her his wife. They marry, and the trio return home to the Miao family home, a hovel made of discarded objects and infested with bats. In a montage, Absurdity redecorates the hovel, and the family live happily for a while, Ciancicato communicating with his new bride through mime. However, an onscreen title tells us that ‘Men are never satisfied with what they have’. Through mime, Ciancicato suggests to Absurdity a plot to raise money: Absurdity will climb to the top of the Coliseum and fake a suicide attempt with the intention that passers-by, rallied by Ciancicato and Basciu, will donate money in order to prevent Absurdity from taking her own life. The plan is carried out, but Absurdity slips on a banana skin and falls to her death.  Distraught, Ciancicato and Basciu are shown weeping at Absurdity’s grave. They return home to find the ghost of Absurdity in their home. They are initially horrified but soon realise that Absurdity’s ghost is the same warm, friendly woman that Absurdity was in life. Ciancicato and Basciu accept her, and the trio continue to live in happiness. The segment ends with an onscreen title: ‘The moral is… to be dead or alive is the same thing’. Distraught, Ciancicato and Basciu are shown weeping at Absurdity’s grave. They return home to find the ghost of Absurdity in their home. They are initially horrified but soon realise that Absurdity’s ghost is the same warm, friendly woman that Absurdity was in life. Ciancicato and Basciu accept her, and the trio continue to live in happiness. The segment ends with an onscreen title: ‘The moral is… to be dead or alive is the same thing’.

In its picaresque structure, broad humour and darkly ironic resolution, ‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’ has a very different tone to the other stories of The Witches. This was because De Laurentiis approached Pasolini after the other stories had been completed, and Pasolini refused to watch the other instalments so as not to ‘become demoralized’ (Pasolini, quoted in Schwartz, 2017: 456). Pasolini later commented that ‘All the other episodes of Le streghe are rather alike, they are all basically anachronistic products of neorealism; even Visconti turned out something poor. All the other episodes are set in a bourgeois milieu and have a brilliant or comic style, so my episode is unassimilable: when it has appeared audiences have just been disconcerted’ (Pasolini, quoted in ibid.: 456-7). Ninetto and Totò play characters with nonsense names (Basciu Miao and Ciancicato Miao, respectively). The characters’ costumes are absurd. In his book Pasolini Requiem, Barth David Schwartz describes them thusly: ‘Ninetto […] wears a carrot-orange punk Wigand a turquoise sweatshirt with NEW YORK written across it. Totò wears a wig of two tufts of acid-yellow curls, like earmuffs bookending his bald head’ (Schwartz, op cit.: 457). Elsewhere, the mise-en-scène features a swirling, mind-bending conflation of vivid Technicolor hues and rundown buildings. (The Miaos’ home is a ramshackle hut made of discarded items.) ‘The Earth Seen from the Moon’ is a witty, playful and deeply satirical segment whose broad humour may alienate some viewers, but its worldview is totally in keeping with the changing paradigms within Pasolini’s body of work during this period.  ‘La Siciliana’ (‘The Sicilian Belle’), directed by Franco Rossi, offers a sharp but very brief parody of neo-realism. The instalment begins with Mangano moulding a doll out of dough before stabbing it angrily. This action is depicted through tight, threatening close-ups. Her father returns home: ‘Who is that man?’, he asks upon seeing the dough-doll, ‘What did he do to you?’ She refuses to tell, and sharp closeups of the pair are intercut, until the father’s escalating anger persuades her to share her story with him. She claims a man looked at her during midnight mass and ‘It kindled a fire in me’. She encountered him again, and he ran away. For this heinous infraction, her father vows to hunt down her unwilling suitor and wreak vengeance upon him. ‘La Siciliana’ (‘The Sicilian Belle’), directed by Franco Rossi, offers a sharp but very brief parody of neo-realism. The instalment begins with Mangano moulding a doll out of dough before stabbing it angrily. This action is depicted through tight, threatening close-ups. Her father returns home: ‘Who is that man?’, he asks upon seeing the dough-doll, ‘What did he do to you?’ She refuses to tell, and sharp closeups of the pair are intercut, until the father’s escalating anger persuades her to share her story with him. She claims a man looked at her during midnight mass and ‘It kindled a fire in me’. She encountered him again, and he ran away. For this heinous infraction, her father vows to hunt down her unwilling suitor and wreak vengeance upon him.

‘The Sicilian Belle’ is a sharp precis of stereotypes associated with Italian cinema of the period: the heated exchanges between Mangano’s character and her father, the periphrasis when dealing with transgressions, the constant references to saints, the sweaty focus on lust as an ‘inciting incident’. At the climax, a bandit shoots people from a moving car; it’s a montage of carnage that leads to a funeral during which the bodies of menfolk are presided over by dramatically distraught women. Mangano shrieks and howls over the corpses, shouting ‘All murdered like miserable dogs. You have abandoned your womenfolk’. In this five minute segment, Rossi savagely foregrounds and dismantles the clichés of Italian cinema.  The final segment is ‘Una sera come le Altre’ (‘An Evening Like the Others’). Directed by Vittorio De Sica’, this segment features Mangano as Giovanna, the frustrated housewife of the American Carlo (Clint Eastwood). (Eastwood’s character, an American who has migrated to Italy, is named Charlie in the English-language version of The Witches.) The final segment is ‘Una sera come le Altre’ (‘An Evening Like the Others’). Directed by Vittorio De Sica’, this segment features Mangano as Giovanna, the frustrated housewife of the American Carlo (Clint Eastwood). (Eastwood’s character, an American who has migrated to Italy, is named Charlie in the English-language version of The Witches.)

The segment intercuts the reality of Giovanna’s domestic life with Carlo, taking place over an evening ‘like the others’, with Giovanna’s daydreams. Giovanna is frustrated with Carlo and his lack of passion for her: ‘I could greet you in the nude and you wouldn’t notice’, she tells him as a sleepy Carlo takes his place in his favourite armchair and begins to drowse. The couple have made plans to go to the cinema, and Carlo struggles to pick a film, suggesting they’re all pretty dire; instead, he suggests, they should simply go to bed… to sleep. A dismayed Giovanna agrees, this evening’s events apparently a recurring paradigm within the couple’s lives. These events are intercut with Giovanna’s daydreams/fantasies, which take place mostly in a highly abstract set decorated in white. These daydreams are passionate and filled with heated exchanges, violence and sex, contrasting entirely with Carlo’s passivity in the real world. ‘An Evening Like the Others’ was filmed between Per qualche dollaro in piu (For a Few Dollars More, 1965) and Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966), Eastwood’s role in this segment playing with his macho screen presence in the Leone westerns all’italiana. He is cast against type as a boring, passionless husband; a clerk who has migrated to Italy from America. At one point, Carlo reads the cinema listings to Giovanna; one of the films playing is Per un pugno di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964). In one of Mangano’s fantasy sequences, her character’s husband Carlo appears as a clad-in-black gunslinger firing towards the camera, a cutaway showing a cinema audience being mowed down by the hail of bullets.  Giovanna fantasises about a passionate relationship with Carlo, who is a cold fish. ‘You’re a funeral, Carlo’, she tells him, ‘You’re monotonous’. As Giovanna washes the dishes in the kitchen, she imagines a scene in which she is clad in a red dress and Carlo presents her with similarly red roses. ‘You hurt me!’, Giovanna accuses Carlo in her daydream. ‘I want to hurt you. I want to destroy you, annihilate you’, a passionate Carlo tells a joyful Giovanna before we are presented with a comic montage depicting the decline in their relationship. In this montage, Giovanna is shown repeatedly on a bed of white linen, her arms outstretched. In 1959, at the start of their relationship, a naked Carlo jumps into bed with Giovanna; in 1962, he jumps into bed again, but this time in a pair of pyjamas; in the present day, 1967, he ambles into bed, collapses on to it and sleeps. ‘They’re always talking about women’s liberation, even the UN’, Giovanna observes in a voiceover, ‘The truth is we’re just slaves, and they’re sultans. Our society is like a harem. We expect so much from America, yet look at this one. He came over here and ended up worse than the rest’. The segment builds towards a climax in which Giovanna imagines a fumetti-like scene in which she is handed around by various comic book superheroes (such as Diabolik), kissing them, whilst Carlo protests weakly, ‘Think of the children’. Giovanna fantasises about a passionate relationship with Carlo, who is a cold fish. ‘You’re a funeral, Carlo’, she tells him, ‘You’re monotonous’. As Giovanna washes the dishes in the kitchen, she imagines a scene in which she is clad in a red dress and Carlo presents her with similarly red roses. ‘You hurt me!’, Giovanna accuses Carlo in her daydream. ‘I want to hurt you. I want to destroy you, annihilate you’, a passionate Carlo tells a joyful Giovanna before we are presented with a comic montage depicting the decline in their relationship. In this montage, Giovanna is shown repeatedly on a bed of white linen, her arms outstretched. In 1959, at the start of their relationship, a naked Carlo jumps into bed with Giovanna; in 1962, he jumps into bed again, but this time in a pair of pyjamas; in the present day, 1967, he ambles into bed, collapses on to it and sleeps. ‘They’re always talking about women’s liberation, even the UN’, Giovanna observes in a voiceover, ‘The truth is we’re just slaves, and they’re sultans. Our society is like a harem. We expect so much from America, yet look at this one. He came over here and ended up worse than the rest’. The segment builds towards a climax in which Giovanna imagines a fumetti-like scene in which she is handed around by various comic book superheroes (such as Diabolik), kissing them, whilst Carlo protests weakly, ‘Think of the children’.

Video

The Witches is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The Witches is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The Witches was released in Italy in a version running 111 mins. An English-dubbed export version with a shorter running time was prepared too. (This latter version features Eastwood’s own voice in the final segment.) This release contains both the Italian-language version of the film (running 111:08 mins) and, as an ‘extra’, the alternate English-dubbed export version (running 104:14 mins). The Italian version takes up 26.9Gb of space on the disc, and the English-language cut takes up 24.9Gb of space. Each segment features a very different photographic style: Visconti’s piece is dominated by a probing, roving camera, whereas Pasolini’s segment feature static camerawork with rigid compositions and vivid colours. Rosi’s entry, on the other hand, is naturalistic and gritty, whilst De Sica’s instalment focuses heavily on the juxtaposition of the earthy tones of Carlo and Giovanna’s apartment with the clinically white setting of Giovanna’s daydreams. The presentation is touted by Arrow as a new 2k restoration based on ‘original film elements’. It’s a solid presentation of the main feature. At a guess, the ‘original film elements’ seem to be a positive source as contrast is quite bold in places, with blacks being slightly ‘crushed’ here and there, and the grain structure is organic but more coarse than one might expect from a transfer coming from a negative source. Colours are reproduced very well, with strong tonal consistency. Fine detail is present throughout, noticeable in close-ups. Midtones have a good sense of tonality and are clearly defined, and the encode to disc presents no problems. It’s a fine, filmlike presentation of the main feature.

Audio

The longer Italian version is presented with a DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono track, accompanied by optional English subtitles. This is satisfyingly ‘bassy’ and has good range. The shorter English version has a DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track too. This track is slightly more ‘tinny’ but is clear and audible throughout. This version of the film is accompanied by optional English subtitles for Hard of Hearing. In both cases, subtitles are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes a commentary by Tim Lucas over the Italian version of the film. Lucas’ commentary is packed with detail, characteristically well-researched and contextualises the film by considering its relationship with portmanteau pictures generally (which Lucas identifies as beginning with Grand Hotel in 1932) and the Italian trend in caroselli pictures – though Lucas seems to mispronounce the title of the Italian television series that gave its name to this trend (the sketch show Carosello, broadcast on RAI between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s; Lucas pronounces the title of this show as caroselli). Lucas considers the work of the various directors and their input into this picture. It’s a breathless commentary track from a dependable contributor.

Overall

The Witches is an interesting though predictably uneven film. Pasolini and Visconti’s segments are thematically rich and work very well, though I’ve always had a strong fondness for ‘The Sicilian Belle’. Though to a large extent a ‘vanity’ project staged by De Laurentiis in order to revitalise the career of his wife Mangano, to be fair Mangano demonstrates a good range in her contributions to the diverse stories contained in this portmanteau picture. In Visconti’s segment, she is essentially asked to essay two characters: the starlet Gloria, her personality hidden behind her various masks, and the ‘real’ and vulnerable Gloria. Pasolini’s segment sees Mangano adopt a naive sweetness in her role as Absurdity. The Witches is an interesting though predictably uneven film. Pasolini and Visconti’s segments are thematically rich and work very well, though I’ve always had a strong fondness for ‘The Sicilian Belle’. Though to a large extent a ‘vanity’ project staged by De Laurentiis in order to revitalise the career of his wife Mangano, to be fair Mangano demonstrates a good range in her contributions to the diverse stories contained in this portmanteau picture. In Visconti’s segment, she is essentially asked to essay two characters: the starlet Gloria, her personality hidden behind her various masks, and the ‘real’ and vulnerable Gloria. Pasolini’s segment sees Mangano adopt a naive sweetness in her role as Absurdity.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of The Witches thankfully contains both the longer Italian version and the shorter English-language export version. The latter should not be overlooked: the dubbing is pretty good, and in the De Sica segment Eastwood’s performance is accompanied by his own voice. The presentation of the main feature is pleasing and Lucas’ commentary is excellent. References: Schwartz, Barth David, 2017: Pasolini Requiem. The University Press of Chicago (Second Edition) (Click to enlarge)

THE WITCH BURNED ALIVE

CIVIC DUTY

THE EARTH AS SEEN FROM THE MOON

THE SICILIAN BELLE

AN EVENING LIKE THE OTHERS

|

|||||

|