|

The Film

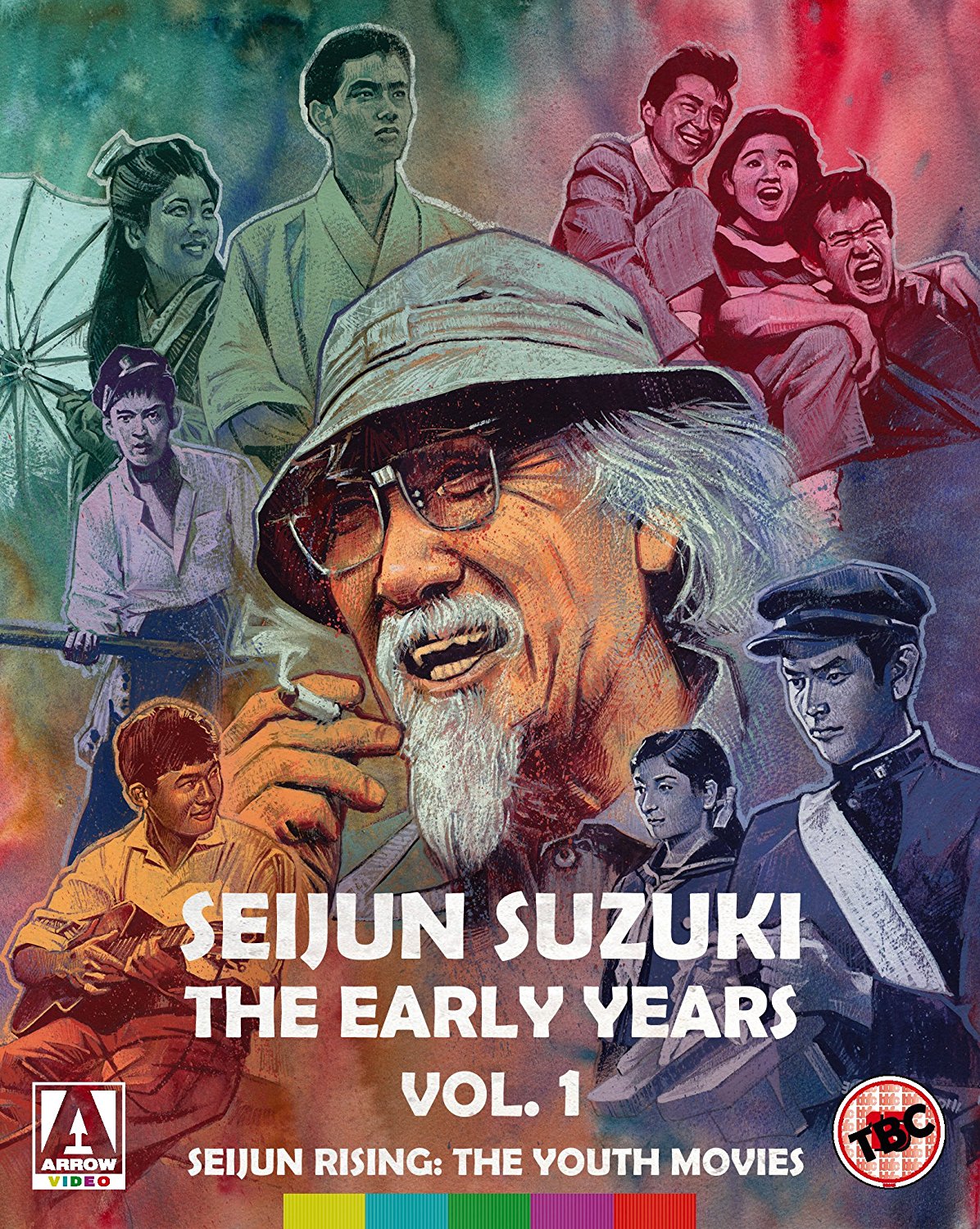

Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years, Vol 1

The Boy Who Came Back (1958). Released from reform school and described as ‘a dormant volcano’, Nubuo Kasahara is placed in the care of Keiko, a young woman from the Big Brothers and Sisters organisation. The Big Brothers and Sisters organisation specialises in finding mentors for wayward young men and women, in the hopes of steering them away from a life of crime. The Boy Who Came Back (1958). Released from reform school and described as ‘a dormant volcano’, Nubuo Kasahara is placed in the care of Keiko, a young woman from the Big Brothers and Sisters organisation. The Big Brothers and Sisters organisation specialises in finding mentors for wayward young men and women, in the hopes of steering them away from a life of crime.

Keiko finds Kasahara to be jumpy and aggressive. She discovers he served time in reform school for attacking his father, a former military man who used to beat Kasahara regularly. Keiko also discovers that Kasahara is in love with a young woman named Kazue, a nursery school teacher. When Keiko witnesses a man being attacked in the street, she discovers Kasahara jumping selflessly to the man’s aid, fighting off his attackers.

Kasahara struggles to find a job, encountering prejudice at every step. Describing himself as ‘just a punk on the road to being a gangster’, Kasahara becomes deeply frustrated. However, recognising a hidden talent for art in the young man, Keiko encourages him to take up portraiture. Doing so, Kasahara begins to find a newfound sense of purpose and direction. This is consolidated when Keiko arranges for Kasahara to spend a day at the beach with Kazue. However, Keiko begins to experience pangs of jealousy, having fallen for Kasahara.

Kasahara’s newfound happiness is short-lived: some of his former criminal associates abduct Kazue and, chloroforming her, subject her to a gang rape. They torment Kasahara with the news of their assault on Kazue. Kashara reacts violently but is beaten by the gang. Further compounding Kasahara’s plight, he is arrested for the assault on the unconscious Kazue, the finger of blame having been pointed at him by his former street punk associates.

The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass (1961). Also known in English as ‘The Breeze on the Ridge’, this film focuses on economics student Shintaro Funaki. Having been laid off by his now bankrupt employer, Funaki finds himself in possession of a bag full of women’s underwear (the only means by which his former employer could pay him). Funaki vows to visit the festival at Sakagi, with the intention of selling these items there. The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass (1961). Also known in English as ‘The Breeze on the Ridge’, this film focuses on economics student Shintaro Funaki. Having been laid off by his now bankrupt employer, Funaki finds himself in possession of a bag full of women’s underwear (the only means by which his former employer could pay him). Funaki vows to visit the festival at Sakagi, with the intention of selling these items there.

Funaki hitches a lift with a truck carrying a troupe of travelling performers, most of them related by blood. At the festival, a wandering yakuza named Ken offers to work as Funaki’s ‘hawker’, in exchange for a percentage of the profits. Meanwhile, the troupe lose their key attraction, a stripper named Akemi, to local gangster Akita; Funaki demonstrates his resourcefulness when he chases Akita off with a trick gun.

The troupe struggle to find bookings with their stripper gone, however. The head of the troupe makes a deal with theatre owner Mr Yamaguchi: he asks Yamaguchi to take a chance and allow them to perform in his theatre. If the show is unsuccessful, the head of the troupe will order his daughter Misako to marry Yamaguchi’s son, who is ‘a little simple since he contracted meningitis’.

The head of the troupe suggests a new star attraction: he will perform a highly dangerous escapology act. However, during rehearsals, he is killed. Without their boss, the troupe struggle to persuade Yamaguchi to allow them to perform, Misako restating her vow to marry Yamaguchi’s son if the show is a failure. Together with Misako, Funaki plots to make the troupe’s show a success.

Teenage Yakuza (1962). Jiro, a young man whose parents are opening a new Westernised coffee shop franchise (Chimoto Coffee), aspires to go to university. However, his plans become frustrated when he finds himself in the middle of a conflict between a group of street punks and the business owners of the district. A group of hoodlums led by a yakuza named Kobayashi are running a protection racket, demanding payment from local shop owners. These hoodlums also rob Jiro and his friend Yoshio, taking their winnings as they return from the racetrack. Teenage Yakuza (1962). Jiro, a young man whose parents are opening a new Westernised coffee shop franchise (Chimoto Coffee), aspires to go to university. However, his plans become frustrated when he finds himself in the middle of a conflict between a group of street punks and the business owners of the district. A group of hoodlums led by a yakuza named Kobayashi are running a protection racket, demanding payment from local shop owners. These hoodlums also rob Jiro and his friend Yoshio, taking their winnings as they return from the racetrack.

Jiro and Yoshio track down the two street punks who robbed them, but in the ensuing scuffle Yoshio is stabbed in the leg, leaving him with a permanent disability. Shortly after this incident, Yoshio’s father is killed in a motorcycle accident, leaving Yoshio and his mother with the unenviable task of trying to collect the debts that were owed to Yoshio’s father before his death.

Embittered, Yoshio tracks down the punk who stabbed him but is stopped from committing an act of revenge by Kobayashi. Kobayashi helps Yoshio by allowing Yoshio to beat the two street punks; however, Yoshio is soon made aware that this is his initiation into Kobayashi’s street gang.

When Kobayashi’s punks attack a local business, Jiro intervenes and humiliates the two hoods. Jiro becomes a local hero, and the business owners offer him money and goods in exchange for his protection. However, Jiro is soon reminded by his mother that this makes him no better than the street punks from whom Jiro is defending the business owners. When Kobayashi railroads several business owners into making a complaint to the police about Jiro, Jiro is arrested. Upon his release, he is asked by Yoshio to join the Nomura gang. Jiro refuses; his refusal places him at odds with his old friend, leading to a bitter climax.

The Incorrigible (1963). Also known in English as ‘The Bastard’ and ‘The Young Rebel’, The Incorrigible focuses on Togo Konno (Yamauchi Ken), a young man from the city of Kobe who, after being expelled from his school over a love affair with the school pastor’s daughter, is sent by his mother to study at a school in the small town of Toyooka. The story takes place in the early Taisho period. The Incorrigible (1963). Also known in English as ‘The Bastard’ and ‘The Young Rebel’, The Incorrigible focuses on Togo Konno (Yamauchi Ken), a young man from the city of Kobe who, after being expelled from his school over a love affair with the school pastor’s daughter, is sent by his mother to study at a school in the small town of Toyooka. The story takes place in the early Taisho period.

In Toyooka, Togo is placed in the care of the headmaster, Yamato. There, Togo meets and becomes fascinated with Emiko, the daughter of the school doctor. Togo dreams of studying literature at university, and he and Emiko bond over a shared love of the work of Strindberg. However, Emiko is being pursued romantically by a senior at the school, Tako the Octopus.

The school has a group of seniors who call themselves the Public Morals Unit. These students inspect the dwellings of junior students in search of items ‘unbecoming to students’, including photographs of girls and examples of pulp fiction. They visit Togo’s dwellings and discover his Strindberg books. Mistaking them for cheap fiction, they chastise Togo, but he turns the tables and educates them on literature. Togo soon makes friends with one of the seniors, Koishi, and the pair play truant from school, persuading Emiko’s father to write each of them a sick note. As Togo and Emiko grow closer, they find their love affair provokes the ire of both Emiko’s father and the Public Morals Unit.

Born Under Crossed Stars (1965). In Kawachi during the early 1920s, Jukichi the Milkboy is attacked whilst delivering milk. Jujichi is the son of an inveterate gambler. He’s a bright young man who has the potential to gain entry to the local grammar school, but he’s held back by his family and background. When Oka, a member of the school’s Discipline Committee, targets Jukichi’s friend Mishima over a petty love rivalry, Jukichi confronts Oka, defeating him in a duel that takes place during a kendo class. Humiliated, Oka leaves the school. Born Under Crossed Stars (1965). In Kawachi during the early 1920s, Jukichi the Milkboy is attacked whilst delivering milk. Jujichi is the son of an inveterate gambler. He’s a bright young man who has the potential to gain entry to the local grammar school, but he’s held back by his family and background. When Oka, a member of the school’s Discipline Committee, targets Jukichi’s friend Mishima over a petty love rivalry, Jukichi confronts Oka, defeating him in a duel that takes place during a kendo class. Humiliated, Oka leaves the school.

Jukichi becomes enchanted with a young woman from the girl’s school, Suzuko Mishima, discovering that she is the sister of a senior at the school who has tormented him. Jukichi makes plans to meet Suzuko in secret, but instead he is met by her friend Taneko, the daughter of the local pawnbroker. The sexually confident Taneko pursues Jukichi in an aggressive manner, eventually seducing him. After spending the night with Jukichi at a hotel, Taneko declares her love for him and becomes displays frighteningly possessive behaviour.

Jukichi is unaware that the hotel is also a location used for gambling, and visiting the hotel to take place in some betting games, Jukichi’s father becomes cognisant of Jukichi’s relationship with Taneko. However, Jukichi’s father’s friend is caught cheating, and both he and Jukichi’s father are beaten up by yakuza members Sentaro and Eikichi.

Vowing revenge, Jukichi attacks Sentaro and Eikichi, blinding one of the yakuza. The pair of gangsters then spend their time searching for Jukichi. Meanwhile, Jukichi declares his love for Suzuko, provoking the ire of Taneko. Events seem to conspire to frustrate Jukichi’s dream of going to university.

In 1956, Nikkatsu began a decade-long run of production of mokukuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures. These films were ‘borderless’ in the sense that they amalgamated elements of Japanese cinema with aspects of American and European cinema, taking something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixing it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. Where earlier jidaigeki (period dramas) had featured Westernised villains, the mokukuseki akushon films tended to feature heroes with Westernised traits. Alongside the mokukuseki akushon pictures, Nikkatsu produced similarly-themed comedies and youth pictures such as those included in this new set from Arrow Video. These films featured Westernised young people: the protagonist of The Incorrigible bonds with his love over a shared interest in the writings of Strindberg; the young people of Teenage Yakuza gather in a new Westernised coffee shop (where, according to one character, ‘they sell coffee and play jazz’), dancing like hipsters to piped jazz and talking about Western literature. Hasakara in The Boy Who Came Back teaches the uptight Keiko to dance to swing music. In Born Under Crossed Stars, the protagonist takes advice in his romantic life from his boss, who has spent time in Texas and wears a cowboy hat, imploring his protégé to court his love in a Western way. In 1956, Nikkatsu began a decade-long run of production of mokukuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures. These films were ‘borderless’ in the sense that they amalgamated elements of Japanese cinema with aspects of American and European cinema, taking something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixing it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. Where earlier jidaigeki (period dramas) had featured Westernised villains, the mokukuseki akushon films tended to feature heroes with Westernised traits. Alongside the mokukuseki akushon pictures, Nikkatsu produced similarly-themed comedies and youth pictures such as those included in this new set from Arrow Video. These films featured Westernised young people: the protagonist of The Incorrigible bonds with his love over a shared interest in the writings of Strindberg; the young people of Teenage Yakuza gather in a new Westernised coffee shop (where, according to one character, ‘they sell coffee and play jazz’), dancing like hipsters to piped jazz and talking about Western literature. Hasakara in The Boy Who Came Back teaches the uptight Keiko to dance to swing music. In Born Under Crossed Stars, the protagonist takes advice in his romantic life from his boss, who has spent time in Texas and wears a cowboy hat, imploring his protégé to court his love in a Western way.

Some of the films in this set invite comparison with contemporaneous youth pictures made around the world which explored the sexual awakening of youth against a framework predicated on inter-generational conflict. This trend, perhaps to some extent stemming from Hollywood films of the 1950s (in particular, two films from 1955: Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause and Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle), finds its localised expression in pictures such as Beat Girl (Edmond T Greville, 1960) and Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush (Clive Donner, 1968), and the films in this set from Suzuki Seijun. From Rebel Without a Cause onwards, youth was a battleground, often filled with ribald humour and the potential of sexual escapades but also packed with danger from street gangs, criminal elements and plain old bullies.

The films, both as a gestalt and individually, juxtapose the city with the countryside and the individual with the group. The focus in all these films seems to be on liminal identities (the space between ‘East’ and ‘West’, between town and country, between the outsider and the community), the protagonists negotiating these territories. As Emiko tells Togo in The Incorrigible, ‘You’re somewhere between an adult and a child’. In The Incorrigible, Togo is sent from Kobe City to study at a rural school in Toyooka. There, he encounters the prejudices of the local youth towards him whilst also demonstrating his own brand of snobbery towards them. Togo is an angry young man in a very similar vein to the contemporaneous protagonists of British New Wave films, such as Tom Courtenay’s Colin Smith in Tony Richrdson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). Upon arriving at the school in Toyooka, Togo is made to sit an entrance exam. Filled with bitterness, he deliberately fails it with the intention of being sent back home. However, Yamato knows Togo’s game and tells Togo that if he fails the entrance exam, he will be made to retake the previous academic year. ‘You have a long life ahead of you’, Yamato reminds Togo, ‘so I’ll slowly knock you down and rebuild you’. Togo rushes back to the exam hall and corrects his answers before submitting his paper. The films, both as a gestalt and individually, juxtapose the city with the countryside and the individual with the group. The focus in all these films seems to be on liminal identities (the space between ‘East’ and ‘West’, between town and country, between the outsider and the community), the protagonists negotiating these territories. As Emiko tells Togo in The Incorrigible, ‘You’re somewhere between an adult and a child’. In The Incorrigible, Togo is sent from Kobe City to study at a rural school in Toyooka. There, he encounters the prejudices of the local youth towards him whilst also demonstrating his own brand of snobbery towards them. Togo is an angry young man in a very similar vein to the contemporaneous protagonists of British New Wave films, such as Tom Courtenay’s Colin Smith in Tony Richrdson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). Upon arriving at the school in Toyooka, Togo is made to sit an entrance exam. Filled with bitterness, he deliberately fails it with the intention of being sent back home. However, Yamato knows Togo’s game and tells Togo that if he fails the entrance exam, he will be made to retake the previous academic year. ‘You have a long life ahead of you’, Yamato reminds Togo, ‘so I’ll slowly knock you down and rebuild you’. Togo rushes back to the exam hall and corrects his answers before submitting his paper.

The protagonists invariably feel abandoned by the parent generation, resulting in a strong sense of resentment. ‘You’re wasting your time if you think you can reform me’, Kasahara tells Keiko in The Boy Who Came Back. In Born Under Crossed Stars, Jukichi wishes to go to university but struggles to better himself owing to the parochial attitudes of his parents. ‘I’ll go to college and take care of you’, he tells his parents in a flashback, but his father responds by asserting, ‘Don’t be stupid! What good came of university?’ Likewise, in The Incorrigible, Togo experiences this sense of abandonment from the parent generation, which is represented in the film through his mother, who at one point tells her son, ‘When I think about you, I feel like shrinking away’. Faced with the seniors at the school, who demand that the junior students bow to them, Togo refuses, asserting that he would ‘rather take a beating than bow’. ‘You’re really extreme’, his new friend tells him. ‘Yes, that’s why I was sent here’, a defiant Togo responds, adding that ‘I’ll leave just as extreme as when I came’. At the school, the seniors line the students up in a gymnasium and beat them viciously for alleged infractions (one student is beaten for being seen in public with a girl – in fact, his cousin; another is beaten for eating at a Western restaurant). The ritualistic dimension of this and the level of cruelty might remind the viewer of the sequence in which the head boys cane the younger students in Lindsay Anderson’s later film If…. (1968). Similar ritualistic punishment is meted out by the Discipline Committee of the school in Born Under Crossed Stars.

The Incorrigible features a sequence that is probably deeply challenging to modern sensibilities, when Togo tells his newfound friend that back home in Kobe City, he lost his virginity to a geisha named Ponta. The events are presented in an extended analepsis, Togo and Ponta’s first meeting taking place on a bridge from which they both fall into a stream below. Ponta takes Togo to a hut where they strip and dry their clothes, Ponta seducing a shy and nervous Togo. As they engage in intercourse in the hut, various men creep up on the building hoping to spot the geisha initiating the spoilt, rich boy into the adult world of sexuality: these images might remind the viewer of the photographer Yushiyuki Kohei’s later 1979 exhibition Koen (‘The Park’). Using a 35mm camera and an infrared flashbulb and shooting between 1971 and 1979, Yushiyuki photographed couples engaged in public coitus in Tokyo’s parks, the photographs revealing groups of men crawling on hands and knees in order to gain a view of these acts of exhibitionism. (Imamura Shohei’s The Pornographers, released a few years after The Incorrigible, in 1966, deals with a similar theme of voyeurism.) Ponta warns them off. After the act, Togo emerges from the hut a completely different young man: the shy nervous Togo has been replaced with a cocky, aggressive youth who also smokes. (It’s a comical moment, rather like the abrupt Jekyll and Hyde-style transformation of Kevin into a stroppy teenager in the first episode of Harry Enfield and Chums, in 1994.) The Incorrigible features a sequence that is probably deeply challenging to modern sensibilities, when Togo tells his newfound friend that back home in Kobe City, he lost his virginity to a geisha named Ponta. The events are presented in an extended analepsis, Togo and Ponta’s first meeting taking place on a bridge from which they both fall into a stream below. Ponta takes Togo to a hut where they strip and dry their clothes, Ponta seducing a shy and nervous Togo. As they engage in intercourse in the hut, various men creep up on the building hoping to spot the geisha initiating the spoilt, rich boy into the adult world of sexuality: these images might remind the viewer of the photographer Yushiyuki Kohei’s later 1979 exhibition Koen (‘The Park’). Using a 35mm camera and an infrared flashbulb and shooting between 1971 and 1979, Yushiyuki photographed couples engaged in public coitus in Tokyo’s parks, the photographs revealing groups of men crawling on hands and knees in order to gain a view of these acts of exhibitionism. (Imamura Shohei’s The Pornographers, released a few years after The Incorrigible, in 1966, deals with a similar theme of voyeurism.) Ponta warns them off. After the act, Togo emerges from the hut a completely different young man: the shy nervous Togo has been replaced with a cocky, aggressive youth who also smokes. (It’s a comical moment, rather like the abrupt Jekyll and Hyde-style transformation of Kevin into a stroppy teenager in the first episode of Harry Enfield and Chums, in 1994.)

Elsewhere, another notable sequence appears in Born Under Crossed Stars, when Jukichi fights Oka during the kendo class. Suzuki intercuts Jukichi and Oka’s fight with shots of a cockfight on which Jukichi’s wastrel father is betting. The use of cross-cutting both establishes a symbolic relationship between the two young men and the fighting cocks, and also underscores Jukichi’s troubled relationship with his father. It’s a clever use of cross-cutting, though the footage of the cockfight is predictably cut by about 28 seconds, removing most of the cockfight footage. (If the disc is played on a region ‘A’ player, however, the cockfight sequence is presented intact.)

Video

All of the films are presented in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio commensurate with the intentions of the filmmakers. All films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

Born Under Crossed Stars and The Incorrigible take up approximately 20Gb of space on disc two; on disc one, Teenage Yakuza fills just over 11Gb of space, The Wind-of-Youth Group… takes up 15Gb of space, and The Boy Who Came Back a little over 16Gb.

The Incorrigible is uncut and runs for 95:05 mins. Born Under Crossed Stars has 28 seconds of cuts to the cockfight sequence and runs for 96:59 mins. (However, if the disc is played on a region ‘A’ player, this film plays uncut.) Teenage Yakuza is uncut with a running time of 71:57 mins. The Boy Who Came Back runs for 99:12. Finally, The Wind-of-Youth Group… runs for 84:35 mins.

The Incorrigible, Born Under Crossed Stars, Teenage Yakuza and The Wind-of-Youth Group… were all shot on monochrome 35mm stock. The films are handsomely presented here. The monochrome pictures feature good contrast, with defined midtones and good, deep blacks. Some minor damage is present here and there. The Incorrigible has some minor scratches and blemishes. Born Under Crossed Stars stutters slightly at approximately 20 minutes into the film. It’s unclear whether this is an issue with the encode or master, but it’s certainly noticeable. Teenage Yakuza has some noticeable fluctuations in the density of the emulsions, especially during the first reel. There are also some pronounced vertical scratches through a good portion of this particular picture.

The Wind-of-Youth Group… is the ‘odd one out’, having been shot on colour 35mm stock. The film features vivid primary colours. This film looks equally handsome though the tonal curve is very sharp in places and one sequence in particular features reds that seem a little over-saturated. Nevertheless, it’s a pleasing presentation of the film, especially given its vintage and relative rarity.

A strong level of fine detail is present throughout all of the films and the presentations retain the structure of 35mm film thanks to a solid encode to disc.

Audio

All five films are presented with LPCM 1.0 audio tracks (in Japanese), with optional English subtitles. In the case of all five films, the audio tracks are clear and audible throughout. The subtitles are easy to read and make sense too.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows:

DISC ONE:

* Teenage Yakuza (71:57)

* The Boy Who Came Back (99:12)

* The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass (84:35)

- Trailers: The Boy Who Came Back (3:35); The Wind-of-Youth Group… (3:51)

- Still Galleries: The Boy Who Came Back (23 images); The Wind-of-Youth Group… (16 images); Teenage Yakuza (13 images)

DISC TWO:

* The Incorrigible (95:05)

* Born Under Crossed Stars (96:59)

- Audio commentary for Born Under Crossed Stars by Jasper Sharp. Sharp provides a breathless and carefully-researched commentary for the last film in the set.

- ‘Tony Rayns on the Youth Films’ (39:39). Rayn delivers an excellent, informative precis of the films in this set.

- Trailers: The Incorrigible (3:38); Born Under Crossed Stars (3:31).

- Still Galleries: The Incorrigible (23 images); Born Under Crossed Stars (20 images).

Overall

Arrow’s new set of Suzuki Seijun pictures is a delight. These films have previously been near-impossible to see outside Japan. The stories are largely clichéd: The Boy Who Came Back, for example, is an immediately recognisable fable of a young man who tries to escape from a life of crime but discovers criminality has a centripetal effect. ‘Even when I try to go straight, they won’t let me’, Kasahara tells Keiko at one point in the film. However, despite their reliance on recognisable narrative paradigms, the films are delivered with an energy and sense of style that would be channelled and amplified in Suzuki’s later pictures. These films are all about rites of passage, though each of them adopts a slightly different approach to narrative: The Wind-of-Youth Group…, for example, employs a picaresque structure, including the incorporation of travelogue-style footage of the festival at Sakagi. Arrow’s new set of Suzuki Seijun pictures is a delight. These films have previously been near-impossible to see outside Japan. The stories are largely clichéd: The Boy Who Came Back, for example, is an immediately recognisable fable of a young man who tries to escape from a life of crime but discovers criminality has a centripetal effect. ‘Even when I try to go straight, they won’t let me’, Kasahara tells Keiko at one point in the film. However, despite their reliance on recognisable narrative paradigms, the films are delivered with an energy and sense of style that would be channelled and amplified in Suzuki’s later pictures. These films are all about rites of passage, though each of them adopts a slightly different approach to narrative: The Wind-of-Youth Group…, for example, employs a picaresque structure, including the incorporation of travelogue-style footage of the festival at Sakagi.

All five films get pleasing presentations in this set, and the accompanying interview with Tony Rayns and commentary (on Born Under Crossed Stars) by Jasper Sharp help to contextualise the pictures. Given the rarity of these films, for fans of Japanese cinema and especially fans of the director, this is an essential purchase.

Large screengrabs (click to enlarge):

Born Under Crossed Stars

Teenage Yakuza

The Boy Who Came Back

The Incorrigible

The Wind of Youth Group…

|