|

|

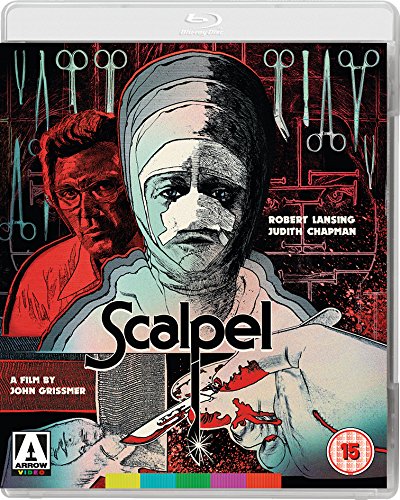

Scalpel AKA False Face (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th February 2018). |

|

The Film

Scalpel (John Grissmer, 1976) Scalpel (John Grissmer, 1976)

When his father-in-law dies, plastic surgeon and widower Dr Philip Reynolds (Robert Lansing) finds himself left out of the will. The only beneficiary is Reynolds’ daughter Heather (Judith Chapman), who has been missing for a year and a half following the death of her lover Donnie (Stan Wojno). Heather stands to inherit five million dollars of her grandfather’s money when she returns. Reynolds drowns his sorrows with his brother-in-law Bradley (Arlen Dean Snyder). However, driving back they encounter a stripper who suffered a terrible facial injury after being beaten by a bouncer. The woman is unconscious; Reynolds rushes her to the hospital. Naming the patient ‘Jane Doe’, Reynolds finds that she is uncommunicative, unable to speak. He uses his skill as a plastic surgeon to rebuild her face, working it into the image of his missing daughter Heather. Eventually, Reynolds reveals his plan to his patient: he will train her to behave and speak like Heather, allowing her to claim the five million dollars inheritance. Once the money has been claimed, Reynolds and Jane will split it equally. The plan works excellently, Jane convincing the lawyers that she is Heather and claiming the money. Once the money is hers, Jane declares her intention to gift half of it to her ‘daddy’.  Jane and Reynolds soon begin a sexual relationship. One day, they are surprised by Bradley, who arrives at Reynolds’ home and, seemingly suspecting something is amiss, demands that Jane play the piano. (The real Heather is a musical prodigy.) Reynolds intervenes, however, and suffering a shock Bradley seems to become the victim of his weak heart. Jane is horrified as Reynolds watches on, not only refusing to help Bradley but also tormenting him, playing ‘Chopsticks’ on the piano as Bradley expires. Jane and Reynolds soon begin a sexual relationship. One day, they are surprised by Bradley, who arrives at Reynolds’ home and, seemingly suspecting something is amiss, demands that Jane play the piano. (The real Heather is a musical prodigy.) Reynolds intervenes, however, and suffering a shock Bradley seems to become the victim of his weak heart. Jane is horrified as Reynolds watches on, not only refusing to help Bradley but also tormenting him, playing ‘Chopsticks’ on the piano as Bradley expires.

After Bradley’s funeral, Reynolds is shocked to discover that the real Heather has returned home. ‘It’s a funny thing about Jane. I’m sure a lot of people mistake her for me’, Heather suggests. Reynolds tells Heather that her grandfather died, suggesting he left his fortune to the University of Atlanta. Jane becomes increasingly jealous of Reynolds’ relationship with Heather. Eventually, Reynolds plots to have Jane removed from his life by bribing a police officer to stage a mock arrest, presumably with the intention of having Jane killed at a different location. However, Jane escapes, leading to an inevitable confrontation between Reynolds, Jane and Heather. One of only two films directed by John Grissmer (the other is 1987’s Blood Rage, released by Arrow on Blu-ray and reviewed by us here), Scalpel – which has also been released under the title False Face – has some superficial similarities to Georges Franju’s Les yeux sans visage (1960) in its focus on an obsessive plastic surgeon and the recurring image of Jane/Heather’s face shrouded in bandages. Like the Franju picture, Scalpel reflects on identity and transformation, seeing the self as largely performative, a theme explored through the indistinguishability/interchangeability of Heather and Jane. ‘I do the devil’s work’, Reynolds says in reference to his work as a plastic surgeon, ‘I change the faces that God intended. I cater to man’s vanity and to his lust’. Jane recognises the sinister aspect of Reynolds’ personality immediately: after he has performed reconstructive surgery on her face and she has regained the ability to speak, she tells him, ‘Ever since you started these operations, there has been something going on in your head and it ain’t medical. Sometimes when you look at me, it’s downright creepy’.  Heather and Jane, though physically alike, are very different in their personalities and backgrounds. Jane struggles to comprehend why Heather might have chosen to leave her life of privilege behind: ‘She had all of this going for her’, Jane says, ‘and she walked away from it. Now that is stupid! [….] I’m not gonna go back to the way I was, am I?’ For his part, Reynolds is motivated solely by material greed. ‘If I imitate Heather, I’ll get all the money’, Jane observes. ‘No’, Reynolds tells her, ‘you’re gonna share some with your “daddy”’. ‘Looks to me like “daddy” has already got enough’, Jane says. ‘No’, Reynolds responds, laughing, ‘There’s never enough’. Soon, Reynolds and Jane’s relationship becomes sexual, Jane seducing Reynolds in a scene that is protracted and uneasy owing to Jane’s resemblance to Reynolds’ daughter Heather. They kiss passionately, Grissmer cutting from their embrace to a point-of-view shot of a rollercoaster car tipping over the top of the hill in the track, this image functioning as a metaphor for their sexual liaison and its intimations of incestuous desire. When the real Heather returns home, Reynolds and Jane’s relationship becomes even more sinister: on the first evening, Reynolds sings a duet with his daughter at the piano before retiring to bed and engaging in intercourse with Jane. Another time, Heather suggests that she and Jane should play a trick on Reynolds by masquerading as one another ‘I wonder how long it would take for him to catch on’, Heather says. ‘Till bedtime’, Jane offers. Finally, towards the end of the film Reynolds tells Heather, ‘She [Jane] was beautiful, but she was just a cheap imitation of what you are. That’s what I was doing: I was making a substitute’. Heather and Jane, though physically alike, are very different in their personalities and backgrounds. Jane struggles to comprehend why Heather might have chosen to leave her life of privilege behind: ‘She had all of this going for her’, Jane says, ‘and she walked away from it. Now that is stupid! [….] I’m not gonna go back to the way I was, am I?’ For his part, Reynolds is motivated solely by material greed. ‘If I imitate Heather, I’ll get all the money’, Jane observes. ‘No’, Reynolds tells her, ‘you’re gonna share some with your “daddy”’. ‘Looks to me like “daddy” has already got enough’, Jane says. ‘No’, Reynolds responds, laughing, ‘There’s never enough’. Soon, Reynolds and Jane’s relationship becomes sexual, Jane seducing Reynolds in a scene that is protracted and uneasy owing to Jane’s resemblance to Reynolds’ daughter Heather. They kiss passionately, Grissmer cutting from their embrace to a point-of-view shot of a rollercoaster car tipping over the top of the hill in the track, this image functioning as a metaphor for their sexual liaison and its intimations of incestuous desire. When the real Heather returns home, Reynolds and Jane’s relationship becomes even more sinister: on the first evening, Reynolds sings a duet with his daughter at the piano before retiring to bed and engaging in intercourse with Jane. Another time, Heather suggests that she and Jane should play a trick on Reynolds by masquerading as one another ‘I wonder how long it would take for him to catch on’, Heather says. ‘Till bedtime’, Jane offers. Finally, towards the end of the film Reynolds tells Heather, ‘She [Jane] was beautiful, but she was just a cheap imitation of what you are. That’s what I was doing: I was making a substitute’.

Scalpel contains some interestingly ambiguous and cleverly-staged sequences. Following the funeral of Reynolds’ father-in-law, we are shown a sequence in which a young man in a car is knocked out and doused in alcohol before being dragged out of the car in which he is sitting and drowned in a lake, the death made to look like a drunken accident. The placing of the events depicted in this sequence is initially ambiguous, but later in the film it is revealed that the young man was Heather’s lover Donnie and his unseen assailant was Reynolds; Heather’s witnessing of this scene from her bedroom window was the catalyst in her decision to flee her home, but unbeknownst to Reynolds, rather than running away, Heather was taken by her grandfather to the nearby mental hospital where she was placed in the care of Dr Dean. The sequence acquires its ‘meaning’ retrospectively, the narrative eventually providing the viewer with enough clues to decode this piece of action.  In another deliciously dark sequence, Reynolds tells Jane of the death of his wife. He informs her that his wife Jenny drowned in an accident at the nearby lake. He tells Jane that the body was found two days later. ‘I blame myself for not being able to save her’, Reynolds says. However, the audience is presented with a visual flashback which undercuts the version of events Reynolds presents to Jane, revealing Reynolds to be an unreliable narrator. In the midground of the shot, we see a woman, presumably Jenny, frantically trying to stay afloat in the lake whilst a pedalboat containing a blasé Reynolds passes her in the background. The juxtaposition between Reynolds’ version of events and what we are shown visually consolidates Reynolds’ position as a dangerous, unreliable protagonist who is characterised by an utter lack of empathy. Reynolds displays the same trait when Bradley dies; Jane is shocked and appalled when Reynolds torments Bradley as he is suffering what seems to be a fatal heart attack. At Bradley’s funeral, Reynolds dryly asserts that Bradley was ‘sitting at the piano, playing his heart out’ just before he died. In another deliciously dark sequence, Reynolds tells Jane of the death of his wife. He informs her that his wife Jenny drowned in an accident at the nearby lake. He tells Jane that the body was found two days later. ‘I blame myself for not being able to save her’, Reynolds says. However, the audience is presented with a visual flashback which undercuts the version of events Reynolds presents to Jane, revealing Reynolds to be an unreliable narrator. In the midground of the shot, we see a woman, presumably Jenny, frantically trying to stay afloat in the lake whilst a pedalboat containing a blasé Reynolds passes her in the background. The juxtaposition between Reynolds’ version of events and what we are shown visually consolidates Reynolds’ position as a dangerous, unreliable protagonist who is characterised by an utter lack of empathy. Reynolds displays the same trait when Bradley dies; Jane is shocked and appalled when Reynolds torments Bradley as he is suffering what seems to be a fatal heart attack. At Bradley’s funeral, Reynolds dryly asserts that Bradley was ‘sitting at the piano, playing his heart out’ just before he died.

Later in the film, Grissmer plays bait-and-switch with the audience when he intercuts a scene of Heather at home, the local plumber arriving at the house to repair the boiler in the basement, with Jane as she swims in the lake watched by Reynolds. In this sequence, there’s some confusion as to which character is Heather and which is Jane, as the two women have previously discussed swapping places in order to confuse Reynolds. Both seem to come a cropper, however. We see the plumber ascending the stairs, blood on his knuckles, and assume that Reynolds has hired the plumber to ‘off’ Heather; we also see Jane floating in the lake in the same manner as Jenny, seemingly dead. However, Grissmer quickly reveals both of these scenarios to be acts of misdirection: the plumber has simply grazed his knuckles during his work, and Jane is merely playing the fool in front of Reynolds. This playfulness and willingness to misdirect the audience is a trait of this film that will either irk viewers or endear them to the picture.

Video

Scalpel is presented uncut, with a running time of 95:06 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Scalpel is presented uncut, with a running time of 95:06 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

Two presentations are available on the disc, and the viewer has the option of switching between the two ‘on the fly’, via the pop-up menu. These two presentations are based on the same master but use different colour grades. The first uses the grade preferred by the film’s director of photography, Edward Lachman. Lachman intended for the film to feature an expressionistic colour grade featuring strong yellows and greens. Alongside this is a more conventional, naturalistic colour grade. The palette of the Lachman-favoured presentation is arguably more evocative, though some viewers may find the yellow hue too overbearing, and I would imagine this is the reason why Arrow have also included a more naturalistic presentation of the film alongside it. Both presentations take up a little over 21Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The presentation is mooted as a 2k restoration from ‘original film elements’. Contrast is pleasing throughout, with defined midtones and deep, dark blacks. Lachman’s preferred colour grade features a sharper tonal curve than the more naturalistic presentation. An excellent level of detail is present throughout the film, fine detail in close-ups satisfying close inspection. There’s no noticeable or harmful damage to the materials. Finally, a robust encode ensures the presentation/s retain the structure of 35mm film. Some large screengrabs comparing the two presentations are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is clean and clear throughout, evidencing good range. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided, and these are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- A commentary with critic Richard Harland Smith. Richard Harland Smith provides an engaging commentary track that explores the film’s relationship with its source material and reflects on the production, discussing the locations and engaging with specific scenes in details. Smith’s comments are informed by some primary research, in the form of interview/s with Grissmer. - Optional Introduction from Grissmer (0:31). The film’s director provides a brief introduction to his film. - ‘The Cutting Edge’ (13:52). In a new interview, Grissmer reflects on his fascination with cinema. He reflects on The Bride (aka Now Way Out/The House That Cried Murder, Jean-Marie Pelissie, 1973), which was his debut as a screenwriter. He discusses the process of casting Scalpel and Judith Chapman’s performance, suggesting their methods for capturing Chapman’s dual role were inspired by the Bette Davis films A Stolen Life (Curtis Bernhardt, 1946) and Dead Ringer (Paul Henreid, 1964). - ‘Dead Ringer’ (17:20). In another new interview, Chapman talks about what attracted her to the film: the dual role, the theme of incest and the ‘operatic themes’. She discusses the Southern setting and its impact on the narrative.

- ‘Southern Gothic’ (15:25). Director of photography Edward Lachman reflects on some of the ways in which his craft has changed. He talks about how he came to be involved in shooting films. He reflects on the photography of Scalpel, which was the first 35mm film he shot. He suggests he wanted to go for a ‘Southern Gothic look’. He wanted to bring out the yellows and greens of the location, so used straw and coral filters on the lenses, resulting in a distinctive ‘look’. His comments are interspersed with some fantastic black and white on-set stills. - Image Gallery (3:31). The gallery includes on-set stills and promotional imagery, both in colour and black-and-white. - Trailer (2:42).

Overall

Filmed in Georgia, Scalpel has a strong sense of place which Lachman emphasises through his photography. The story has some superficial similarities with Les yeux sans visage (and its many imitators, such as Jess Franco’s Gritos en la noche (The Awful Dr Orlof, 1962). It’s an interesting film, with a theme of doubling which was in vogue during the 1970s (for example, Robert Mulligan’s 1972 film The Other) and would be revisited in Grissmer’s second feature Blood Rage (1987). Grissmer employs some clever narrative devices, and the intimations of incest are unsettling. Scalpel is a darkly entertaining film, and Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a solid presentation of this previously hard-to-see picture. The two presentations are quite different, though Lachman’s preferred presentation is perhaps the best way to watch the film. There’s some excellent and thorough contextual material too. This is an impressive release of a mostly forgotten film. Filmed in Georgia, Scalpel has a strong sense of place which Lachman emphasises through his photography. The story has some superficial similarities with Les yeux sans visage (and its many imitators, such as Jess Franco’s Gritos en la noche (The Awful Dr Orlof, 1962). It’s an interesting film, with a theme of doubling which was in vogue during the 1970s (for example, Robert Mulligan’s 1972 film The Other) and would be revisited in Grissmer’s second feature Blood Rage (1987). Grissmer employs some clever narrative devices, and the intimations of incest are unsettling. Scalpel is a darkly entertaining film, and Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a solid presentation of this previously hard-to-see picture. The two presentations are quite different, though Lachman’s preferred presentation is perhaps the best way to watch the film. There’s some excellent and thorough contextual material too. This is an impressive release of a mostly forgotten film.

Large screengrabs (click to enlarge; Edward Lachman grade on top; naturalistic grade beneath):

|

|||||

|