|

|

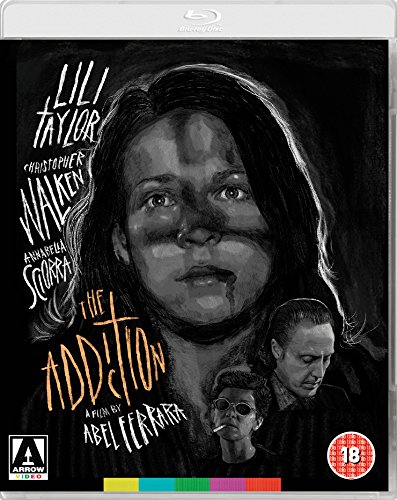

Addiction (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th June 2018). |

|

The Film

The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995)

After she is attacked in an alleyway by a mysterious woman (Annabella Sciorra) who bites her throat, PhD student Kathleen Conkin (Lili Taylor) begins to change. Her body is weakened; she is unable or unwilling to eat. Kathleen also questions her academic work, asking her friend Jean (Edie Falco), ‘You ever question the sanity of bothering to do a dissertation on these idiots’, in reference to the philosophers whose work she is studying. At first, Kathleen is concerned that she might have contracted the AIDS virus, but soon she begins to show a desire for the drinking of blood. She begins with nameless victims, junkies on the streets of the city, but soon vampirises her thesis supervisor (Paul Calderon) and an anthropology student (Kathryn Erbe) she meets in the university library. Kathleen meets Peina (Christopher Walken), initially approaching him as a victim. However, she is soon forced into the realisation that Peina is also a vampire. Peina claims to be in control of his urges and promises to teach Kathleen ‘what you are’. He bleeds Kathleen dry, using her blood for his own sustenance. Afterwards, Kathleen comes to a new awareness of herself, addiction and the nature of evil. Kathleen completes her thesis and passes her doctorate. In celebration, she arranges a soiree for the faculty members and her fellow students, but she also invites many of the people she has vampirised. These vampires attack and feast on the guests from the university. However, Kathleen becomes sick and ends up in hospital, where she is visited by a priest (Father Robert W Castle) and comes to seek redemption. The figure of the vampire, and its association with parasitic blood-sucking and social inequality (the aristocratic vampire feeding on the plebeian class), seemed like the perfect metaphor for the 1990s; particularly when relocated from exotic lands to a modern urban setting, the vampire in American cinema often assumed a role as a symbolic representative of the yuppie mindset, like a Patrick Bateman with supernatural powers.  An off-kilter vampire picture by cult director Abel Ferrara, The Addiction was made at a time when indie filmmakers such as Ferrara and some of his contemporaries (for example, Michael Almereyda, in his 1994 picture Nadja) were exploring the allegorical potential of stories about vampires and vampirism; along with Nadja and its use of the lo-fi Fisher Price PixelVision camera, Ferrara’s film stood in contrast to Hollywood’s increasingly spectacle-oriented, glossy vampire narratives of the era, such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (1992) and Neil Jordan’s adaptation of Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire (1994). An off-kilter vampire picture by cult director Abel Ferrara, The Addiction was made at a time when indie filmmakers such as Ferrara and some of his contemporaries (for example, Michael Almereyda, in his 1994 picture Nadja) were exploring the allegorical potential of stories about vampires and vampirism; along with Nadja and its use of the lo-fi Fisher Price PixelVision camera, Ferrara’s film stood in contrast to Hollywood’s increasingly spectacle-oriented, glossy vampire narratives of the era, such as Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (1992) and Neil Jordan’s adaptation of Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire (1994).

Like Almereyda’s Nadja, Ferrara chose to shoot The Addiction in stark black-and-white. (The recent and acclaimed A Girl Walks Alone At Night, directed by Ana Lily Amirpour in 2014, adopted a similar tactic.) Ferrara made The Addiction pretty much back-to-back with The Funeral, which is one of the most critically neglected films of the 1990s. The Addiction and The Funeral were the last two Ferrara films to be scripted by Nicholas St John, with whom Ferrara had collaborated since his days making short films in the early 1970. Like many of the films on which Ferrara and St John worked together, these two pictures feature a strong focus on themes of faith and redemption. Both The Addiction and The Funeral also feature overlapping cast members (Christopher Walken and Annabella Sciorra), and both films were hampered by poor distribution and a general lack of ‘push’ either critically or commercially at the time of their original releases. Subsequently, both films have since been difficult to see in decent versions on home video. Joan Hawkins has derided the lack of critical interest in The Addiction at the time of its initial release, noting that ‘[w]hile the much tamer Wolf (Mike Nichols, 1994) was praised in the mainstream press for its implicit critique of corporate downsizing and capitalist greed, The Addiction’s explicit retooling of vampirism as another example of [William S] Burrough’s junk pyramid did not elicit the critical commentary it deserved’ (Hawkins, 2003: 14). The result of this was that a film which, in Hawkins’ opinion, ‘should have cemented Ferrara’s status with both the mainstream “independent” and underground audiences […] had the reverse effect of solidifying his status as a primarily underground director’ (ibid.).  In The Addiction, Ferrara foregoes the trappings of most vampire films, setting his story in modern-day New York. As the title suggests, Ferrara frames vampirism as having an equivalency with drug addiction, but with a striking level of insight the film also explores the existential crisis of someone studying at doctoral level. The film focuses on Kathleen Conkin, a graduate student in philosophy played by Lili Taylor, who is vampirised by a mysterious woman (Annabella Sciorra). Conkin must wrestle with her newfound ‘addiction’, whilst cognisant of the ethical and philosophical implications of her need to feed on the blood of others. Walken plays a vampire who claims to have overcome his need for blood and tries to encourage Kathleen to kick her ‘addiction’. In The Addiction, Ferrara foregoes the trappings of most vampire films, setting his story in modern-day New York. As the title suggests, Ferrara frames vampirism as having an equivalency with drug addiction, but with a striking level of insight the film also explores the existential crisis of someone studying at doctoral level. The film focuses on Kathleen Conkin, a graduate student in philosophy played by Lili Taylor, who is vampirised by a mysterious woman (Annabella Sciorra). Conkin must wrestle with her newfound ‘addiction’, whilst cognisant of the ethical and philosophical implications of her need to feed on the blood of others. Walken plays a vampire who claims to have overcome his need for blood and tries to encourage Kathleen to kick her ‘addiction’.

In terms of cultural references, the film openly discusses underground drug culture, the panic over AIDS, philosophy, the Holocaust, the My Lai massacre and the then-current Bosnian genocide. The narrative conflates vampirism, a symbolically loaded practice within horror fiction, and the genocidal mindset, underpinning this with a discussion of philosophy that points to a critique of what could best be labelled ‘ideological vampirism’. The film opens with a lecture on the My Lai massacre, a slideshow presented onscreen with offscreen narration from the episcopal priest/actor Father Robert W Castle, who also appears later in the picture as a priest that administers the last rites to Kathleen. This lecture provokes a debate between Kathleen and her classmate Jean about guilt and ethics, Kathleen suggesting that its fallacious to pin the guilt for such a war crime on a single participant (in this case, Lt William Calley): ‘It’s the whole country’, Kathleen argues, ‘They were all guilty. How do you single out one man?’ ‘Well, you can’t jail a whole country’, Jean responds. This dialogue, with its dialectical structure, sets the tone for the rest of the film, the majority of which revolves around conversations in which one point of view is placed against its ideological opposite. ‘If you’re prosecuting war crimes’, Kathleen continues, ‘you gotta make sure that more than one man takes the blame for everything. It’s ridiculous’.  After this dialogue ends, Kathleen walks the streets alone, Ferrara offering an almost cinema verite-like depiction of inner city life, accompanied on the soundtrack by Cypress Hill’s ‘I Wanna Get High’. This is followed by Kathleen being dragged into an alleyway and attacked by Annabella Sciorra’s vampire, named as Casanova in the film’s credits, which is framed as a moment of domination in which the vampire asserts her will over Kathleen. ‘Look at me and tell me to go away. Don’t ask; tell me’, Casanova declares. Kathleen, however, is frozen in fear, almost giving herself to the vampire and experiencing a moment of ecstasy as her throat is bitten. Kathleen’s ambivalence to the assault, her willingness to let herself be taken by Casanova even when presented with an ‘out’, is conflated with Kathleen’s fascination with the ghetto – her insistence on walking the streets alone, despite her friend’s protestations that it’s dangerous. In both cases, all Kathleen needs to do, in order not to be a victim, is assert her will. The fact that Casanova’s attack takes place in a darkened alleyway within the urban ghetto draws a subtle equivalency between vampirism and the act of dealing drugs. As Casanova walks away, she mutters a single word to Kathleen: ‘Collaborator’. Thrown at Kathleen in reference to her lack of resistance, the word has import beyond the immediate narrative context in which it is presented, connecting Kathleen’s passive acceptance of her domination by the vampire with the film’s references to acts of genocide and war. As Joan Hawkins suggests, ‘the hunger for blood – in all its manifestations – is disturbingly figured in the film as an addiction’ (Hawkins, op cit.: 15). After this dialogue ends, Kathleen walks the streets alone, Ferrara offering an almost cinema verite-like depiction of inner city life, accompanied on the soundtrack by Cypress Hill’s ‘I Wanna Get High’. This is followed by Kathleen being dragged into an alleyway and attacked by Annabella Sciorra’s vampire, named as Casanova in the film’s credits, which is framed as a moment of domination in which the vampire asserts her will over Kathleen. ‘Look at me and tell me to go away. Don’t ask; tell me’, Casanova declares. Kathleen, however, is frozen in fear, almost giving herself to the vampire and experiencing a moment of ecstasy as her throat is bitten. Kathleen’s ambivalence to the assault, her willingness to let herself be taken by Casanova even when presented with an ‘out’, is conflated with Kathleen’s fascination with the ghetto – her insistence on walking the streets alone, despite her friend’s protestations that it’s dangerous. In both cases, all Kathleen needs to do, in order not to be a victim, is assert her will. The fact that Casanova’s attack takes place in a darkened alleyway within the urban ghetto draws a subtle equivalency between vampirism and the act of dealing drugs. As Casanova walks away, she mutters a single word to Kathleen: ‘Collaborator’. Thrown at Kathleen in reference to her lack of resistance, the word has import beyond the immediate narrative context in which it is presented, connecting Kathleen’s passive acceptance of her domination by the vampire with the film’s references to acts of genocide and war. As Joan Hawkins suggests, ‘the hunger for blood – in all its manifestations – is disturbingly figured in the film as an addiction’ (Hawkins, op cit.: 15).

In the hospital and her apartment afterwards, Kathleen is unsure of what has happened: like the audience, for whom the fantastical associations of vampires clash with the contemporary urban setting of the story, she believes her assault simply to be a random attack by a maniac on the streets. This is compounded by the words of a police officer at the hospital, who asserts that Kathleen is ‘lucky she didn’t cut your throat’. Kathleen suffers emotional shock; through a montage we see her reacting to the wound on her throat as she removes the dressing in the apartment of her bathroom and weeps, then writhes in despair and agony on her bed.  Later, Kathleen demonstrates a similar power over her victims to the manner in which Casanova dominated her; Kathleen asserts in an instant of offscreen narration that ‘It makes no different what I do, whether I draw blood or not. It’s the violence of my will against theirs’. When she lures the anthropology student to her apartment, Ferrara depicts the attack elliptically, cutting to the aftermath as Kathleen, blood on her lips, watches images of the Bosnian genocide on television whilst the anthropology student weeps in the bathroom. ‘What the hell were you thinking?’, Kathleen asks the anthropology student, ‘Why didn’t you tell me to go?’ ‘I was afraid you’d hurt me’, the anthropology student sobs. ‘Worse than I’ve done?’, Kathleen asks mockingly. ‘I don’t even know what you’ve done’, the anthropology student cries, ‘Am I gonna get sick now?’ ‘No worse than you were before’, Kathleen responds. ‘How could you do this?’, the anthropology student begs, ‘Doesn’t this affect you at all?’ ‘No’, Kathleen barks back, ‘It was your decision [….] My indifference is not the concern here: it’s your astonishment that needs studying’. Later, Kathleen demonstrates a similar power over her victims to the manner in which Casanova dominated her; Kathleen asserts in an instant of offscreen narration that ‘It makes no different what I do, whether I draw blood or not. It’s the violence of my will against theirs’. When she lures the anthropology student to her apartment, Ferrara depicts the attack elliptically, cutting to the aftermath as Kathleen, blood on her lips, watches images of the Bosnian genocide on television whilst the anthropology student weeps in the bathroom. ‘What the hell were you thinking?’, Kathleen asks the anthropology student, ‘Why didn’t you tell me to go?’ ‘I was afraid you’d hurt me’, the anthropology student sobs. ‘Worse than I’ve done?’, Kathleen asks mockingly. ‘I don’t even know what you’ve done’, the anthropology student cries, ‘Am I gonna get sick now?’ ‘No worse than you were before’, Kathleen responds. ‘How could you do this?’, the anthropology student begs, ‘Doesn’t this affect you at all?’ ‘No’, Kathleen barks back, ‘It was your decision [….] My indifference is not the concern here: it’s your astonishment that needs studying’.

Kathleen soon develops her lust for blood, which is framed in the same way as an addiction to heroin. Seeing a junkie on the street, a needle in his arm, Kathleen uses the syringe to take a little of his blood and inject it into herself. Shortly afterwards, luring her lecturer (Paul Calderon) to her apartment, she wanders out of the room as if she is going to offer him a drink. However, she returns with a tray containing a junkie’s paraphernalia (a spoon, a candle, needles) and offers him heroin (‘Dependency is a marvellous thing’, she tells him, ‘It does more for the soul than any formulation of doctoral material’). Though the film presents the subsequent series of actions elliptically, it’s clear that Kathleen takes his blood after he is incapacitated from the ‘hit’: a slow pan over his semi-conscious body reveals she has written ‘IN’ and ‘OUT’ next to the fresh trackmarks in his forearm. When Kathleen meets Peina, the language he uses directly conflates vampirism with junkiedom (‘You can never get enough, can you? But you learn to control it. You learn, like the Tibetans, to survive on a little’), even going so far as to refer to Burrough’s Naked Lunch as a novel with an astute understanding of what it means to go ‘cold turkey’ from both drugs and vampirism. (‘Burroughs perfectly describes what it’s like to go without a fix’, Peina tells Kathleen.)  Kathleen’s edginess is captured in the film’s photography. After she has been bitten by Casanova, Kathleen begins to change. In the cafeteria, she sits with Jean but does not eat her food; the camera moves slowly but continuously, revolving around the table and creating a subtle sense of unease. In the preface to Naked Lunch, Burroughs asserted that ‘The face of “evil” is always the face of total need. A dope fiend is a man in total need of dope. Beyond a certain frequency need knows absolutely no limit or control. In the words of total need: “Wouldn’t you?” Yes you would. You would lie, cheat, inform on your friends, steal, do anything to satisfy total need. Because you would be in a state of total sickness, total possession, and not in a position to act in any other way’ (Burroughs, 2012: xxxix). Like the most desperately addicted – to blood, to drugs, to ideology, to cruelty – in the face of her need, questions of morality and ethics don’t have any import for her. ‘So what you been doing, then?’ Peina asks her, ‘What do you have inside? Any kids? Any children? The first one’s the hardest, isn’t it? After that, they’re like all the rest’. After her encounter with Peina, Kathleen narrates over images of the Holocaust in an exhibition, asserting that ‘I finally understand what all this is. How it was all possible. Now I see. Good Lord, how we must look from out there. Our addiction is evil. The propensity for this evil lies in our weakness before it. Kierkegaard was right. There is an awful precipice before us. But he was wrong about the leap. There’s a difference between jumping and being pushed’. Kathleen’s edginess is captured in the film’s photography. After she has been bitten by Casanova, Kathleen begins to change. In the cafeteria, she sits with Jean but does not eat her food; the camera moves slowly but continuously, revolving around the table and creating a subtle sense of unease. In the preface to Naked Lunch, Burroughs asserted that ‘The face of “evil” is always the face of total need. A dope fiend is a man in total need of dope. Beyond a certain frequency need knows absolutely no limit or control. In the words of total need: “Wouldn’t you?” Yes you would. You would lie, cheat, inform on your friends, steal, do anything to satisfy total need. Because you would be in a state of total sickness, total possession, and not in a position to act in any other way’ (Burroughs, 2012: xxxix). Like the most desperately addicted – to blood, to drugs, to ideology, to cruelty – in the face of her need, questions of morality and ethics don’t have any import for her. ‘So what you been doing, then?’ Peina asks her, ‘What do you have inside? Any kids? Any children? The first one’s the hardest, isn’t it? After that, they’re like all the rest’. After her encounter with Peina, Kathleen narrates over images of the Holocaust in an exhibition, asserting that ‘I finally understand what all this is. How it was all possible. Now I see. Good Lord, how we must look from out there. Our addiction is evil. The propensity for this evil lies in our weakness before it. Kierkegaard was right. There is an awful precipice before us. But he was wrong about the leap. There’s a difference between jumping and being pushed’.

Throughout the film, as in many of his other pictures (for example, 1990’s King of New York), Ferrara juxtaposes wealth with poverty; this conflict is expressed in the spaces used in his films, which take on a symbolic charge. Here, in The Addiction, Ferrara contrasts the streets, bodegas and alleyways – populated by young, mostly black, men whose behaviour initially intimidates Kathleen – with university lecture theatres, libraries, coffee shops and galleries. For Kathleen and her fellow students, the former are seen as threatening spaces: at the start of the picture, Kathleen exits the university and runs the gauntlet on her way home, passing a group of young black men, one of whom propositions her. (Later, after she has been ‘vampirised’ and has transitioned from prey to predator, Kathleen responds to this young man’s ‘come on’, matching his suggestive banter.) When Casanova makes her appearance to Kathleen in the alleyway near the start of the film, Casanova’s appearance – tall and erect, she is dressed in black evening gown – is at odds with the poverty of her setting. (By contrast, as Kathleen’s vampirism escalates, she looks increasingly like a street junkie – in scruffy clothes, wearing dark glasses, and her body language turned inwards.) Emanuel Levy has suggested that this juxtaposition of wealth and poverty within the narratives of Ferrara’s films is matched by the fact that in ‘film after film, Ferrara’s high art and philosophical ambitions clash with his more natural disposition for lowlife sleaze’ (Levy, 1999: 120). Nowhere in Ferrara’s career is this more evident than in The Addiction, which infuses the ‘lowly’ genre of vampire fiction with dialogue that is openly philosophical – flowing out of its protagonist’s statement as a PhD student.  Speaking of which, whilst through its mise-en-scène the film juxtaposes the story-spaces of the university with those of the ‘street’, The Addiction also contrasts Kathleen’s two mentors: the university-sanctioned thesis supervisor (Paul Calderon) and Peina, the street-level philosopher who tries to draw Kathleen to an awareness of who she is. As Calderon’s lecturer tells his class near the start of the film, ‘One aspect of determinism is centred on the fact that the unsaved don’t recognise the sin in their lives. They’re unconscious of it [….] They don’t suffer pangs of conscience because they don’t recognise evil exists [….] When considering the salvatory aspect of facing guilt, suffering is a good thing’. (This monologue is echoed later in the film, when Peina bleeds Kathleen dry and tells her ‘Whatever good is in you, I will use for sustenance, and for you it will feel as though you haven’t eaten for weeks. Demons suffer in hell’.) Kathleen’s narrative is the story of her growing awareness of sin, her acknowledgement of its role in her life, and her attempt, ultimately, to find some sort of redemption. She is aided in this by Peina, who encourages her to suffer by literally bleeding her dry, using her lifeforce for his own sustenance to the extent that like a junkie jonesing desperately for a fix, Kathleen is reduced to trying to cut into her own veins in order to get a ‘hit’ of blood. ‘You can’t kill what’s dead’, Peina tells her, ‘Eternity’s a long time. Get used to it’. Speaking of which, whilst through its mise-en-scène the film juxtaposes the story-spaces of the university with those of the ‘street’, The Addiction also contrasts Kathleen’s two mentors: the university-sanctioned thesis supervisor (Paul Calderon) and Peina, the street-level philosopher who tries to draw Kathleen to an awareness of who she is. As Calderon’s lecturer tells his class near the start of the film, ‘One aspect of determinism is centred on the fact that the unsaved don’t recognise the sin in their lives. They’re unconscious of it [….] They don’t suffer pangs of conscience because they don’t recognise evil exists [….] When considering the salvatory aspect of facing guilt, suffering is a good thing’. (This monologue is echoed later in the film, when Peina bleeds Kathleen dry and tells her ‘Whatever good is in you, I will use for sustenance, and for you it will feel as though you haven’t eaten for weeks. Demons suffer in hell’.) Kathleen’s narrative is the story of her growing awareness of sin, her acknowledgement of its role in her life, and her attempt, ultimately, to find some sort of redemption. She is aided in this by Peina, who encourages her to suffer by literally bleeding her dry, using her lifeforce for his own sustenance to the extent that like a junkie jonesing desperately for a fix, Kathleen is reduced to trying to cut into her own veins in order to get a ‘hit’ of blood. ‘You can’t kill what’s dead’, Peina tells her, ‘Eternity’s a long time. Get used to it’.

It’s a divisive film, and as absurd as it sounds, it’s also strikingly accurate in terms of the emotions one passes through when studying for a doctorate: the sense of hunger to achieve, doubt and internal conflict whilst writing the thesis being communicated through the film’s protagonist’s newfound addiction. (Though the film’s depiction of its protagonist’s doubts about her thesis ring true from the perspective of someone who has firsthand experience of studying towards a doctorate, the film’s representation of the processes involved in academic work at that level is a little ‘off’ – particularly the suggestion that PhD students attend lectures and seminars in their discipline, though admittedly perhaps this is the case in American universities.) Ferrara’s films are often deliberately obscure, refusing to pander to perceptions of what audiences want and finding their own direction; The Addiction is no exception, its mixture of philosophy, horror and deeply black humour still resonating today and marking it as different to other films of its kind – if, indeed, there are any.

Video

The 1080p presentation of The Addiction is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and uses the AVC codec. The main feature takes up 23Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 82:21 mins. The 1080p presentation of The Addiction is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and uses the AVC codec. The main feature takes up 23Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 82:21 mins.

The Addiction has been difficult to see in a good home video incarnation. The film was released on LaserDisc by Polygram in its intended aspect ratio, but most of the subsequent DVD releases of the film featured 4:3 presentations which were cropped (rather than presented open-matte). The best DVD presentation was from Arthaus in Germany: this presentation retained the film’s intended aspect ratio. Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation is exceptional, a huge improvement on all of the film’s previous home video releases. The film is presented in a restoration based on a 4k scan of the original negative. The presentation has been approved both by Ferrara and the film’s cinematographer Ken Kelsch. A superb level of detail is present throughout he film, fine detail being particularly noticeable in closeups. The high contrast monochrome photography is captured beautifully on this Blu-ray, which has excellent contrast levels. Midtones are rich and have a strong sense of definition to them, and blacks are deep and rich. Aided by a solid encode to disc, the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. The result is a very organic, filmlike viewing experience. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via the option of a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track or a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both of these tracks are clean and clear, the 5.1 track naturally featuring some additional sound separation. But given the film’s original soundscape isn’t ‘showy’ in terms of its design, the LPCM 2.0 track is an equally pleasing option. Either way, on both tracks the audio Is deep and rich, with a strong sense of depth and range. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- an audio commentary with Abel Ferrara. This new audio commentary sees Ferrara in conversation with Brad Stevens. Ferrara points out the misspelling of Paul Calderon’s surname in the film’s opening credits. Ferrara discusses the logistics of filmmaking – or, specifically, filmmaking in his style. At one point, Stevens asks Ferrara if he needed permission to shoot in the city streets and if the people walking in the background are extras. Ferrara’s response: ‘There ain’t no fucking extras; this is fucking a street. What do you think, I’m fucking directing these people? Don’t start with these crazy questions. We’re shooting a street, bro; what the fuck, you know [….] You think we could set this shit up, dog? That’s being right there. That’s why these films count’, he comments over the shots in which Kathleen is approached on the city streets. Stevens asks Ferrara about the chiaroscuro lighting in the scene in which Casanova attacks Kathleen, and Ferrara responds by telling him ‘It [the light] was probably just there and we worked it, you know. It’s taking what’s there, taking it to the next level’. For fans of Ferrara, this commentary track is essential, offering insight into the director’s approach to filmmaking. - ‘Talking with the Vampires’ (30:55). Directed by Ferrara himself, this new documentary incorporates interviews with Taylor and Walken alongside comments from composer Joe Delia and cinematographer Ken Kelsch. Ferrara’s management of this material is rough and includes someone (offscreen) telling Taylor to clap her hands in place of the slate marking the start of the shot, and Walken’s comical response to the clapping of the slate as his interview begins. Taylor talks about how she prepared for the role by walking through the streets of New York at night, and Walken discusses the difficulty of finding good roles when an actor hits their 70s. Walken reveals himself to be interested in vampire films and suggests The Addiction ‘had really original things’ to say about the genre. Walken talks about his approach to acting, saying that ‘I learn the lines; I never think about, you know, what it would be like to be a vampire’. It’s a fascinating documentary, Ferrara’s relationships with the interviewees managing to put them at ease and coax some illuminating comments from them.

- Interview with Abel Ferrara (16:19). In a new interview, Ferrara discusses his relationship with the film, admitting that there aren’t many films with a female protagonist, so when one comes along ‘it’s special’. He praises the monochrome aesthetic: ‘the ones [films] that really count are black and white’, he says, ‘You wanna make at least one feature film in black and white’. He discusses the logistics of shooting with a single camera: ‘You had one camera, and you’re lucky if you had that’. He can’t remember if they used video assist on the production, but ‘We’re shooting old school, bro. The guy shooting, he either gets it or he don’t. There might be take two, but definitely no take three’. Ferrara discusses the logistics of making and financing an independent film, suggesting that it was essential that the crew agree to work not for a salary but for promise of payment later, but that this can backfire – as on Dangerous Game (1993), a project on which Ferrara and his crew were stiffed by some shady distributors. He suggests that ‘once you start begging for money’ and ‘once the budget starts going up, you’re not shooting movies like this’. - Appreciation by Brad Stevens (8:47). Stevens compares The Addiction to Ms 45 (1981), suggesting that the two films overlap in interesting ways. He suggests that like Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), The Addiction is a film that, he argues, people admire ‘for the wrong reasons’. - ‘Abel Edits The Addiction’ (8:43). An excellent addition to the overall package, this footage shows Ferrara, in true livewire form, during the editing of The Addiction. Ferrara talks about the film, discussing some of its ideas, drinks wine, plays some music and praises the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (‘he’s coming at you a mile a minute with fucking ideas, you know; he’s got more ideas in five minutes of his films than Hollywood has had in the last two years’). - Gallery (18 black and white stills). Trailer (0:36).

Overall

Like many of Ferrara’s films, particularly those on which he collaborated with Nicholas St John, underneath all the layers within The Addiction is a reflection on the possibility of redemption. Though perhaps not quite as good as The Funeral, the film which Ferrara made pretty much back-to-back with this picture, The Addiction is a strong, distinctive piece of work. Ferrara’s stamp is all over the picture. The direct references within the script of The Addiction to philosophy ‘made reviewers on opposing sides of the cultural divide label the film as “pretentious” (a word that took on both derisive and celebratory nuances, depending on the user’s cultural point of reference)’ (Hawkins, op cit.: 14). For those in tune with Ferrara’s mindset, this is a superb film. Like many of Ferrara’s films, particularly those on which he collaborated with Nicholas St John, underneath all the layers within The Addiction is a reflection on the possibility of redemption. Though perhaps not quite as good as The Funeral, the film which Ferrara made pretty much back-to-back with this picture, The Addiction is a strong, distinctive piece of work. Ferrara’s stamp is all over the picture. The direct references within the script of The Addiction to philosophy ‘made reviewers on opposing sides of the cultural divide label the film as “pretentious” (a word that took on both derisive and celebratory nuances, depending on the user’s cultural point of reference)’ (Hawkins, op cit.: 14). For those in tune with Ferrara’s mindset, this is a superb film.

The Addiction has been difficult to see in good home video incarnations, and Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray presentation remedies this. Alongside a very pleasing high definition presentation of the main feature, Arrow’s release includes an audio commentary with Ferrara and a new documentary about the film, made by Ferrara himself and including input from Ferrara and other participants in the making of the film. The archival footage of Ferrara during the editing of the film is a delight, in particular. For anybody interested in Ferrara’s body of work, this is an essential release and will no doubt be one of the most significant releases of the year. References: Burroughs, William S, 2012: Naked Lunch: The Restored Text. London: Harper Collins Hawkins, Joan, 2003: ‘No Worse Than You Were Before: Theory, Economy and Power in Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction’. In: Mendik, Xavier & Schneider, Steven Jay (eds), 2003: Underground USA: Filmmaking Beyond the Hollywood Canon. Columbia University Press: 13-25 Levy, Emanual, 1999: Cinema of Outsiders: The Rise of American Independent Film. New York University Press McDermott, Morna & Daspit, Toby, 2005: In: Edgerton, Susan et al (eds), 2005: Imagining the Academy: Higher Education and Popular Culture. London: RoutledgeFalmer: 190-203 Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|