|

|

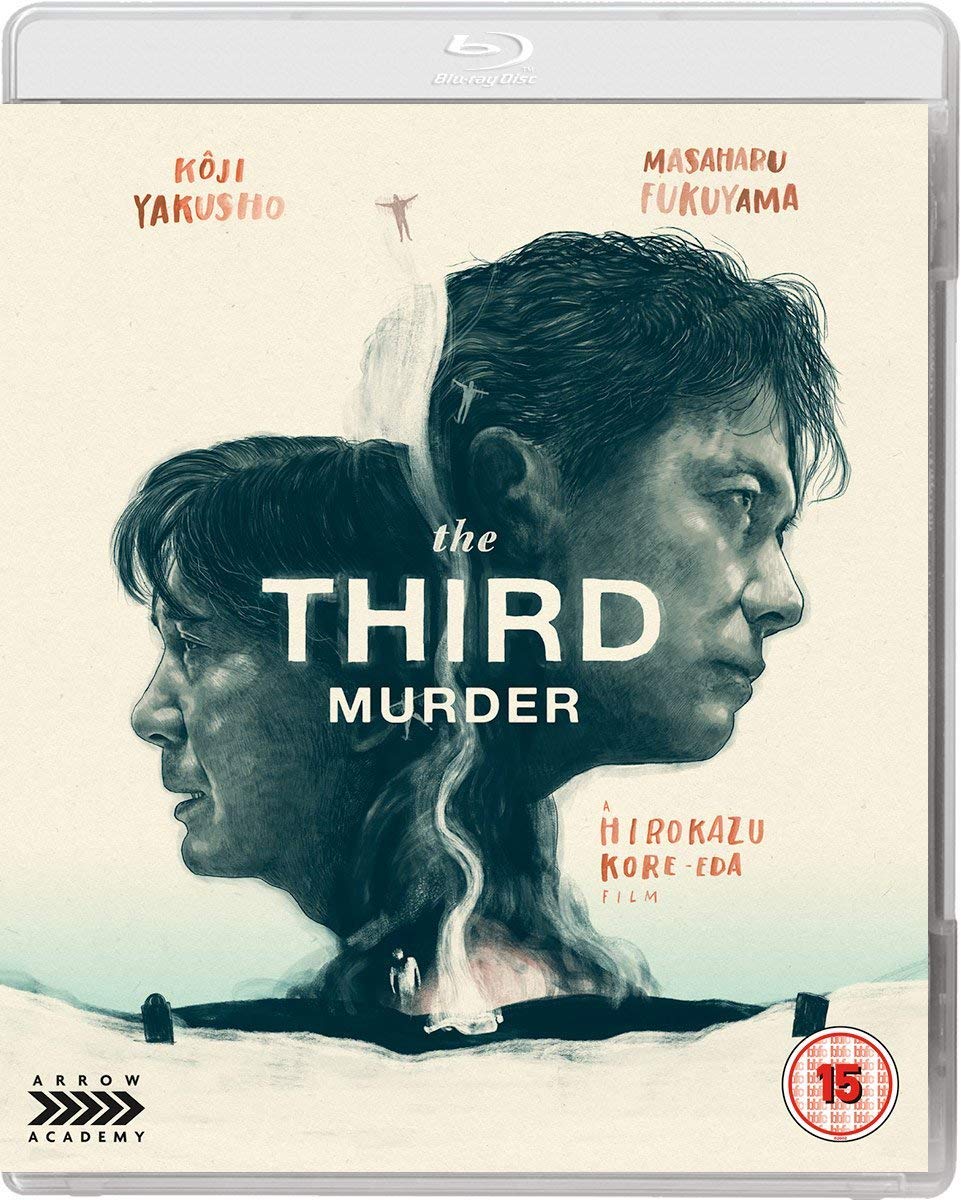

Third Murder (The) AKA Sandome no satsujin (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th August 2018). |

|

The Film

The Third Murder (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2017) The Third Murder (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2017)

By a river, factory owner Yamanaka Mitsuo is murdered, his corpse set alight; the murder is apparently committed by one of Mitsuo’s employees, Misumi (Yakusho Koji). Mitsuo had a reputation of hiring, and exploiting, ex-cons; Misumi is no exception, having previously served 30 years in prison for the murder of two loan sharks in Hokkaido. Then, Misumi narrowly missed the death sentence, thanks to the liberal ruling of the presiding judge, Shigemori Akihisa (Hashizume Isao). Now, the quiet and unassuming Misumi is to be defended by Judge Shigemori’s son (Fukuyama Masaharu). As the younger Shigemori takes the case, he is informed that Misumi has already confessed to the murder, and Misumi was found with the victim’s wallet in his possession. Misumi’s guilt doesn’t seem to be in question. Shigemori and his team’s job is simply to try to prevent Misumi from being executed for the crime. This hinges on Misumi’s motive, something which Shigemori struggles to understand owing to inconsistencies in Misumi’s story. At first, Shigemori tries to prove that Misumi didn’t commit the murder with the intention to steal the wallet but instead took it as an afterthought, which if true would mean Misumi might escape being executed for the crime. Misumi has an adult daughter, Megumi, who still lives in Hokkaido. However, Misumi is estranged from her, and Shigemori debates whether or not to travel to Hokkaido to interview her as a character witness. Misumi’s alienation from his daughter mirrors Shigemori’s own cold relationship with his 14 year old daughter Yuka (Makita Aju), a petty criminal who displays a chilling ability to distort the truth and cry on demand in order to get her own way.  A magazine article is published which suggests that Misumi was paid by Mitsuo’s wife Mizue to kill her husband. Shigemori investigates this as a possible motive for the murder. He also discovers that Misumi was visited regularly by a teenage girl. Misumi identifies this girl as being Sakie (Hirose Suzu), the daughter of the victim. Digging further, Misumi discovers that Sakie was being abused sexually by her father, and that Misumi was offering her the warmth and shelter she was missing at home – presumably seeing Misumi as a surrogate daughter. Shigemori begins to believe that Misumi may have killed Mitsuo in order to protect Sakie, or perhaps Sakie killed her father and Misumi confessed to the murder. A magazine article is published which suggests that Misumi was paid by Mitsuo’s wife Mizue to kill her husband. Shigemori investigates this as a possible motive for the murder. He also discovers that Misumi was visited regularly by a teenage girl. Misumi identifies this girl as being Sakie (Hirose Suzu), the daughter of the victim. Digging further, Misumi discovers that Sakie was being abused sexually by her father, and that Misumi was offering her the warmth and shelter she was missing at home – presumably seeing Misumi as a surrogate daughter. Shigemori begins to believe that Misumi may have killed Mitsuo in order to protect Sakie, or perhaps Sakie killed her father and Misumi confessed to the murder.

Japanese film director Kore-eda Hirokazu began his career in documentaries before moving on to the world of fictional narrative cinema. Kore-eda is primarily associated with naturalistic stories about families, such as I Wish, Like Father, Like Son and After the Storm. With The Third Murder, which is not his most recent film but the most recent of his films to be released in the UK, Kore-eda has delivered an incisive courtroom drama which focuses on Misumi, a convicted murderer, recently released from prison, who commits another killing. Misumi is caught and, if convicted, faces death by hanging. Misumi has confessed to the crime but a lawyer named Shigemori, who has been tasked with defending Misumi, believes that there must be a mitigating motive for the murder. Shigemori tries to tease from Misumi the ‘truth’ of the event but struggles to comprehend Misumi’s vague and non-committal responses to his questions. Visiting Hokkaido to speak with Watanabe, the detective who arrested Misumi for killing the two loan sharks, Shigemori is informed that during Misumi’s previous trial, he kept changing his story in a similar way, Watanabe asserting that ‘It was like he [Misumi] was an empty vessel’.  As Tony Rayns explains in the interview contained on this disc, Japanese courtroom dramas are few and far between, the inner workings of the Japanese legal system being a relative mystery (at least in terms of their representation in fiction). In Japan the outcomes of criminal trials are largely expected to be resolved before the various parties set foot in the courtroom; the trial is simply a validation of a version of events that has already been reached by consensus through interviews and liaison between the legal teams responsible for prosecuting and defending the accused. By the time a case reaches the courts, the guilt of the accused is assumed to have been proven. As a consequence, Japan has for a long time had a consistently high conviction rate. In 2009, Japan introduced a lay judge system, having abolished trial by jury in 1943 (after the concept had only been introduced to Japan’s legal system only 15 years previously, in 1928). The lay judge system is sometimes confused with trial by jury; though the two are quite different, they both involve ordinary citizens issuing rulings in criminal trials. This has had repercussions in term of the conviction rate, and also in terms of Japan’s use of the death penalty, with a feeling that if a capital case is presented in front of a lay judge, they will shy away from issuing the death penalty. Some have suggested that this has resulted in a spike in the number of prisoners on ‘death row’ petitioning for retrials (Nippon Communications Foundation, 2018: np). As Tony Rayns explains in the interview contained on this disc, Japanese courtroom dramas are few and far between, the inner workings of the Japanese legal system being a relative mystery (at least in terms of their representation in fiction). In Japan the outcomes of criminal trials are largely expected to be resolved before the various parties set foot in the courtroom; the trial is simply a validation of a version of events that has already been reached by consensus through interviews and liaison between the legal teams responsible for prosecuting and defending the accused. By the time a case reaches the courts, the guilt of the accused is assumed to have been proven. As a consequence, Japan has for a long time had a consistently high conviction rate. In 2009, Japan introduced a lay judge system, having abolished trial by jury in 1943 (after the concept had only been introduced to Japan’s legal system only 15 years previously, in 1928). The lay judge system is sometimes confused with trial by jury; though the two are quite different, they both involve ordinary citizens issuing rulings in criminal trials. This has had repercussions in term of the conviction rate, and also in terms of Japan’s use of the death penalty, with a feeling that if a capital case is presented in front of a lay judge, they will shy away from issuing the death penalty. Some have suggested that this has resulted in a spike in the number of prisoners on ‘death row’ petitioning for retrials (Nippon Communications Foundation, 2018: np).

The murder which Misumi is presumed to have committed (though later sequences in the film cast doubt upon this) seems, for much of the film, to be lacking in clear motive. This, and the film’s subtle examination of the dualism between determinism and the notion of free will, results in a narrative that has echoes of the murder that the narrator-protagonist Meursault commits in Albert Camus’ 1942 existential novel L’etranger (published in English as The Outsider or The Stranger). Misumi shares Meursault’s curious affectlessness. Kore-eda’s film also seems self-consciously indebted to Rashomon, with each version of the murder that Shigemori uncovers during his investigations serving only to further obscure the truth of the matter. Like Akira Kurosawa’s film adaptation of Rashomon before it, The Third Murder is ultimately about the impossibility of knowing the ‘truth’ of any event: people’s behaviour, and their actions, are a puzzle. Even our own actions often become a puzzle to us as time passes and our memories distort our understanding of them. After speaking to a lawyer friend, Kore-eda became fascinated with the idea of a courtroom as a place not in which the truth is uncovered but in which it is further concealed by the various conflicting narratives that are presented there. This became the basis for The Third Murder.  At its heart, like most of Kore-eda’s films, The Third Murder is about family: Misumi’s alienation from his adult daughter mirrors workaholic Shigemori’s alienation from his teenage daughter (and the breakdown of Shigemori’s relationship with his wife). Shigemori begins to see Misumi as a dark echo of himself: both men are deeply lonely, with a shared deterministic worldview. In one of several uncanny comments Misumi makes towards Shigemori, Misumi deduces Shigemori has a daughter. Both men’s isolation from their children is offset by the sexual abuse to which the murder victim subjected his daughter, the reason why she confided in Misumi (and possibly the reason why Misumi killed him, or alternatively confessed to the murder in order to protect the real culprit, which may or may not have been the victim’s daughter). The film also explores the relationship between Shigemori and his father, the judge who tried Misumi for the murder of two loan sharks 30 years earlier, and who now expresses to his son his regret at not giving the death penalty to Misumi; doing so, Shigemori’s father reasons, would have prevented Misumi from committing another murder. At its heart, like most of Kore-eda’s films, The Third Murder is about family: Misumi’s alienation from his adult daughter mirrors workaholic Shigemori’s alienation from his teenage daughter (and the breakdown of Shigemori’s relationship with his wife). Shigemori begins to see Misumi as a dark echo of himself: both men are deeply lonely, with a shared deterministic worldview. In one of several uncanny comments Misumi makes towards Shigemori, Misumi deduces Shigemori has a daughter. Both men’s isolation from their children is offset by the sexual abuse to which the murder victim subjected his daughter, the reason why she confided in Misumi (and possibly the reason why Misumi killed him, or alternatively confessed to the murder in order to protect the real culprit, which may or may not have been the victim’s daughter). The film also explores the relationship between Shigemori and his father, the judge who tried Misumi for the murder of two loan sharks 30 years earlier, and who now expresses to his son his regret at not giving the death penalty to Misumi; doing so, Shigemori’s father reasons, would have prevented Misumi from committing another murder.

Shigemori finds himself swamped by the case, almost obsessively attempting to identify Misumi’s motive for murdering his employer, despite initially telling a member of his team that ‘You don’t need to understand or empathy [sic] to defend a client [….] You’re not going to become friends’. Shigemori is initially cynical vis-à-vis the importance of the concept of ‘truth’: when a colleague asks him ‘Which is the truth, a grudge or life insurance?’, Shigemori answers, ‘Whichever is advantageous to the client [….] We’ll never know which is the truth. So we choose whatever benefits the case’. However, Shigemori soon comes to recognise the similarities between himself and Misumi, including their estrangement from their respective daughters. Shigemori also learns that the murdered Mitsuo wasn’t a particularly pleasant man: through speaking with Sakurah, one of Misumi’s colleagues, Shigemori discovers that Mitsuo hired men with criminal records ‘because we were cheap. You can’t fight back if you have a weakness’. Later in the story, Shigemori comes to the realisation that Mitsuo was sexually abusing his daughter, Sakie, and Misumi was apparently showing kindness towards Sakie – and may have killed Mitsuo to protect Sakie (or, alternately, Sakie killed her father and Misumi confessed to the crime to protect her from the legal system). For his attempts to engage with Misumi, however, Shigemori is chastised by the prosecution team, who accuse Shigemori of being ‘the kind of lawyer that gets in the way of criminals facing their guilt’.  Shigemori also comes into conflict with his father, the judge who convicted Misumi of the murders of the two loan sharks 30 years earlier. Judge Shigemori was lenient in his verdict, giving Misumi 30 years in prison rather than the death penalty. However, Judge Shigemori expresses regret over this, suggesting that if he had given Misumi the death penalty, Misumi wouldn’t have been able to commit another murder. Judge Shigemori also expresses to his son a belief that the motives of a man like Misumi are unknowable: ‘He just wanted to kill’, Judge Shigemori says, ‘Kill for fun and then burn him. Some people are more beast than human’. Judge Shigemori expresses a deterministic view of human behaviour: ‘There’s a huge gap separating those who kill and those who don’t. Whether or not you cross that gap is determined at birth’. His son challenges this assertion, suggesting that ‘That’s an awfully arrogant statement. You don’t even believe in rehabilitation?’ In response, Judge Shigemori states that ‘You’re the arrogant one if you believe people can change so easily’, adding later, ‘Don’t waste your time trying to figure him out [….] People hardly understand members of their own family, let alone strangers’. Shigemori also comes into conflict with his father, the judge who convicted Misumi of the murders of the two loan sharks 30 years earlier. Judge Shigemori was lenient in his verdict, giving Misumi 30 years in prison rather than the death penalty. However, Judge Shigemori expresses regret over this, suggesting that if he had given Misumi the death penalty, Misumi wouldn’t have been able to commit another murder. Judge Shigemori also expresses to his son a belief that the motives of a man like Misumi are unknowable: ‘He just wanted to kill’, Judge Shigemori says, ‘Kill for fun and then burn him. Some people are more beast than human’. Judge Shigemori expresses a deterministic view of human behaviour: ‘There’s a huge gap separating those who kill and those who don’t. Whether or not you cross that gap is determined at birth’. His son challenges this assertion, suggesting that ‘That’s an awfully arrogant statement. You don’t even believe in rehabilitation?’ In response, Judge Shigemori states that ‘You’re the arrogant one if you believe people can change so easily’, adding later, ‘Don’t waste your time trying to figure him out [….] People hardly understand members of their own family, let alone strangers’.

Video

Presented uncut and with a running time of 124:51 mins, Arrow’s 1080p presentation of The Third Murder employs the AVC codec and takes up 32Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Presented uncut and with a running time of 124:51 mins, Arrow’s 1080p presentation of The Third Murder employs the AVC codec and takes up 32Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc.

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The Third Murder is the first film Kore-eda has made in widescreen, which given the courtroom setting of most of the film might seem to be an odd choice. However, Kore-eda’s use of the widescreen framing is reminiscent of Richard Fleischer’s 1959 courtroom drama Compulsion and finds new ways of representing static compositions involving characters interviewing one another or statements being presented to the court. The compositions are stately and formal, the photography making much use of glass and reflection in order to delineate the relationships between the characters, especially between Misumi and Shigemori. The Third Murder was shot digitally, in colour. As a digitally-shot feature, the film has a very crisp and ‘clean’ aesthetic. Detail is superb throughout, the presentation communicating a sense of depth. Colours are balanced, consistent and naturalistic. Contrast levels are excellent, with low light scenes containing detail in the shadows and balanced highlights; midtones have a strong sense of definition throughout. The photography contains much use of chiaroscuro lighting, communicating a sense of depth, and this is captured excellently in this Blu-ray presentation of the film. Some full-sized screengrabs are presented at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

There are two audio options: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track and a LPCM 2.0 track. Both tracks are clear with a good sense of depth and range. The film’s sound design isn’t ‘showy’, but the 5.1 track comes alive with ambient sound, offering a slightly richer soundscape than the LPCM track. Dialogue is in Japanese throughout, with optional English subtitles provided These are easy to read and mostly error free, though there are some very minor grammatical errors that appear here and there.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An interview with Tony Rayns (38:04). Rayns situates the film within the career of its director, Kore-eda Hirokazu, and explores the picture’s depiction of the Japanese legal system. He reflects on the fact that Japanese courtroom dramas are few and far between and discusses the film’s approach to capital punishment. Rayns demonstrates his usual affability and attention to detail. - ‘The Making of The Third Murder’ (30:04). This featurette looks at the making of the picture and features footage from the film intercut with interviews with Kore-eda and the cast. We see footage of preproduction meetings, allowing a glimpse into Kore-eda’s approach to planning the shoot. Behind-the-scenes footage of the production is included too. The featurette is guided by a female voiceover. Spoken language is Japanese, with optional English subtitles being provided. - Introduction by Cast Members (1:53). Fukuyama, Yakusho and Hirose provide brief spoken introductions to the film, in Japanese, with accompanying optional English subtitles. - Behind the Scenes Image Gallery (10:10). - Trailers and TV Spots: UK theatrical trailer (1:32); Japanese theatrical trailer (1:33); Japanese teaser (0:33); Japanese TV spot 1 (0:18); Japanese TV spot 2 (0:18).

Overall

Kore-eda’s The Third Murder is a fascinating film, though as Tony Rayns suggests in the interview contained on this disc, some understanding of the Japanese legal system may be required to comprehend elements of the story. Kore-eda’s use of the widescreen frame is surprisingly effective, having some similarities with Richard Fleischer’s 1959 film about the Leopold and Loeb case, Compulsion, also shot in widescreen and largely based in a courtroom. At its heart, though, despite being posited as a turning point in its director’s career The Third Murder is, like many of Kore-eda’s films, about family and the forces that pull families apart. It’s a powerful film, subtle in its approach and filled with subtext. Kore-eda’s The Third Murder is a fascinating film, though as Tony Rayns suggests in the interview contained on this disc, some understanding of the Japanese legal system may be required to comprehend elements of the story. Kore-eda’s use of the widescreen frame is surprisingly effective, having some similarities with Richard Fleischer’s 1959 film about the Leopold and Loeb case, Compulsion, also shot in widescreen and largely based in a courtroom. At its heart, though, despite being posited as a turning point in its director’s career The Third Murder is, like many of Kore-eda’s films, about family and the forces that pull families apart. It’s a powerful film, subtle in its approach and filled with subtext.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of The Third Murder is tip-top and is accompanied by some very good contextual material. The interview with Tony Rayns is typically thorough, and the ‘making of’ featurette is an impressive one, giving some strong insight into Kore-eda’s approach to filmmaking. In all, it’s a very good release. References: Nippon Communications Foundation, 2018: ‘Capital Punishment in Japan’. [Online.] https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00239/ Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|