|

|

The Film

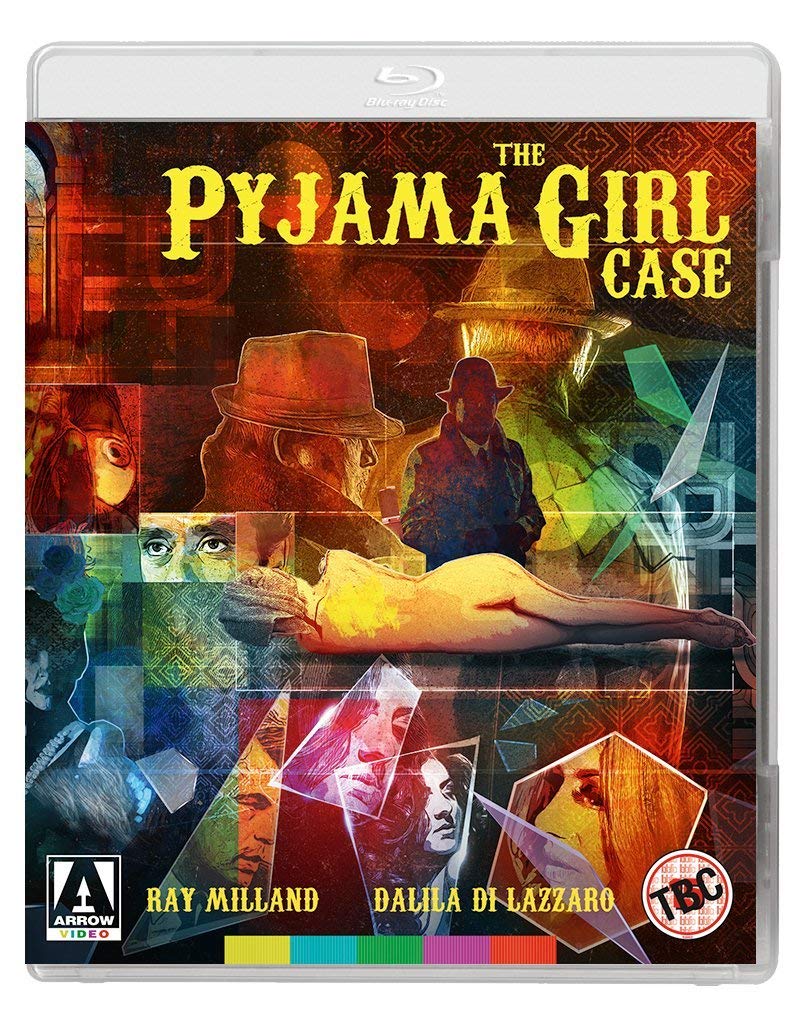

La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (The Pyjama Girl Case, Flavio Mogherini, 1977) La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (The Pyjama Girl Case, Flavio Mogherini, 1977)

New South Wales, Australia. Following the discovery of a partially-burnt female corpse in an abandoned car on a beach, investigating detective Morris (Rod Mullinar) calls in retired detective Thompson (Ray Milland). Thompson clashes with Taylor, the younger, more corporate-minded lead detective on the case, who believes the dead woman – who suffered a gunshot wound to the head before being bludgeoned to death, her face shrouded with a towel, her body wrapped in yellow pyjamas and partially-burnt – was the victim of what he calls a ‘sex maniac’ with a ‘castration complex’. Thompson has a different opinion, believing there is a much more rational motivation behind the murder and accusing Taylor of being too obsessed with trendy psychoanalytic theory. The investigation is intercut with the story of Linda (Dalila di Lazzaro; named Glenda in the Italian version of the film), the murdered woman. Linda has three lovers: wealthy professor Henry Douglas (Mel Ferrer; a doctor in the Italian version), Danish immigrant Roy Conner (Howard Ross) and Italian immigrant Antonio Attolini (Michele Placido), who is introduced to Linda by Roy. Linda falls pregnant but is unsure who the father is. She persuades Antonio that he is the father of the baby, and he proposes to her. Linda agrees to marry Antonio but suffers a miscarriage. Antonio supports her but afterwards, Linda quickly becomes frustrated with their proletarian existence, desiring to return to her relationship with the wealthy Henry. She leaves Antonio for Henry, but Henry turns her away. Distraught and hit with the realisation that her promiscuity has alienated her from everyone, Linda takes up an offer made to her by a sleazy man in a roadside café: in exchange for a hundred dollars, she sells her body to the man, his friend and a 13 year old boy who is travelling with them. Meanwhile, egged on by Roy, Antonio is on the hunt for his wife.  The plot of La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (Flavio Mogherini, 1977) is very loosely based on the (in)famous 1934 case of a female corpse that was discovered in New South Wales. (This case is arguably the Australian equivalent of the Black Dahlia.) The corpse was the victim of murder: the woman had been shot in the head and bludgeoned; a towel had been wrapped round her skull, she had been concealed in a culvert, and someone (presumably her murderer) had tried to set her alight using kerosene. The plot of La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (Flavio Mogherini, 1977) is very loosely based on the (in)famous 1934 case of a female corpse that was discovered in New South Wales. (This case is arguably the Australian equivalent of the Black Dahlia.) The corpse was the victim of murder: the woman had been shot in the head and bludgeoned; a towel had been wrapped round her skull, she had been concealed in a culvert, and someone (presumably her murderer) had tried to set her alight using kerosene.

After the police failed to identify the corpse, they had it preserved in a bath of formalin at the Sydney University Medical School where the body was put on public exhibition in the hope that a member of the public would be able to identify the victim. One of the key features about the body were the yellow pyjamas with which the body was found; the pyjamas had a dragon embroidered upon them, and at the time of Great Depression the luxuriousness of these pyjamas set the victim apart from the bulk of society. The presence of the pyjamas with the corpse led the case to be known as the ‘pyjama girl case’. After ten years, the corpse was claimed to be that of one of two women: Anna Philomena Morgan or Linda Agostini. Evidence of a dental examination pointed to Linda being the most likely identity of the body. In 1944, Linda Agostini’s husband Tony, an Italian immigrant to Australia, returned to the country after being held as a POW in the Second World War, and after being questioned by the police he confessed to the murder of his wife: Agostini claimed he shot her accidentally and then, in a fit of panic, drove the body to the countryside and set it alight in the hope of destroying any evidence that might implicate him in the death of his wife. However, in 2004 a book by historian Richard Evans, entitled The Pyjama Girl Mystery, suggested that though Agostini had confessed to murdering his wife and dumping her body, certain details point to the corpse discovered in the pyjama girl case not being that of Linda Agostini: in particular, Linda and the corpse had different coloured eyes.  Like Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films), Mogherini’s La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (The Pyjama Girl Case, 1977) is a hybrid of Italian-style thriller and police procedural – though the presence of the word ‘giallo’ in the film’s title seems intentionally used as an index of the picture’s relationship with the Italian-style thrillers of the period. Like Massimo Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films), Mogherini’s La ragazza dal pigiama giallo (The Pyjama Girl Case, 1977) is a hybrid of Italian-style thriller and police procedural – though the presence of the word ‘giallo’ in the film’s title seems intentionally used as an index of the picture’s relationship with the Italian-style thrillers of the period.

The film presents a dual narrative: the first of these is the poliziesco all’italiana-like investigation into the corpse discovered on the beach, led by Morris and Taylor but assisted by amateur sleuth Thompson – a retired detective who has emigrated from Canada to Australia. This takes place in the diegetic present and is intercut with scenes from the life of Linda (named ‘Glenda’ in the Italian version of the film) and her relationships with three lovers: wealthy doctor Henry, and immigrants Roy and Antonio, the latter of whom she marries. These events take place in the past, in terms of the film’s diegesis, though a first-time viewer might be forgiven for believing that these two narrative strands, intercut with one another, are taking place at the same time. (What gives the game away, more than anything else, is the use of ellipses in the narrative strand featuring Linda: lines in the dialogue allude to the passage of weeks and even, at certain point, months, whilst the investigation of Thompson, Taylor and Morris takes place over a much more compact period of time.)  The film contrasts Thompson’s way of working with that of Taylor. Though his spectacles may initially be taken as an index of sensitivity and intellectualism (which Thompson sneers at when he criticises Taylor’s recursion to psychoanalytic models of behaviour), Taylor’s approach to getting a confession seems to focus on finding a likely suspect and then beating a confession out of him. When Taylor suggests that the victim was raped and murdered by a man with a ‘castration complex’, Thompson pooh-poohs the younger detective’s recourse to psychoanalytic discourse: ‘The kid’s head is full of that crap they teach you in college’, Thompson tells Nottingham in reference to Taylor, ‘Stuff about analysis, psychoanalysis, sexual deviation and all that’. For his part, Taylor tells Morris that Thompson should ‘go back to Canada where he bloody well belongs’, adding that ‘He’s past it. His methods are out of date’. The film contrasts Thompson’s way of working with that of Taylor. Though his spectacles may initially be taken as an index of sensitivity and intellectualism (which Thompson sneers at when he criticises Taylor’s recursion to psychoanalytic models of behaviour), Taylor’s approach to getting a confession seems to focus on finding a likely suspect and then beating a confession out of him. When Taylor suggests that the victim was raped and murdered by a man with a ‘castration complex’, Thompson pooh-poohs the younger detective’s recourse to psychoanalytic discourse: ‘The kid’s head is full of that crap they teach you in college’, Thompson tells Nottingham in reference to Taylor, ‘Stuff about analysis, psychoanalysis, sexual deviation and all that’. For his part, Taylor tells Morris that Thompson should ‘go back to Canada where he bloody well belongs’, adding that ‘He’s past it. His methods are out of date’.

By contrast, Thompson’s methodology involves plenty of legwork and speaking with grassroots experts: Thompson sneaks a few grains of rice, found on the body, out of the lab and visits restaurants in order to determine the precise type of rice and where it may have come from. As the film starts, Thompson is shown to be a keen horticulturalist, but he is frustrated with his retirement: ‘I want to work again’, he says, ‘I’m standing around doing nothing but climbing up walls’. However, chief inspector Nottingham (Antonio Ferrandis) tells Thompson to ‘enjoy your old age […] Times have change. Modern delinquents are a different breed’. Nottingham continues, offering some subtle foreshadowing: ‘Age isn’t on your side and God knows what you might run into with a case of this kind’, he tells the ageing sleuth. Shortly afterwards, Thompson meets Taylor in a restaurant and tells him, ‘In the old days, a policeman didn’t sit with his back to a window. Some hoodlum could get it in his head to shoot you from a car’. It’s a line of dialogue that offers a very subtle moment of prolepsis towards a plot point that attempts to capture something of the effect of the extraordinary coup de theatre that Hitchcock achieved in Psycho (1960).  This contrast between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ is also mirrored in Linda’s story. Bisexual and promiscuous, Linda is also deeply materialistic. Whilst the film attempts to present Linda as sympathetic, and Dalila di Lazzaro’s performance goes a long way in selling this, it’s difficult not to see the film as ‘punishing’ Linda for her ‘modern’ ways (through her pregnancy and her lack of certainty as to who the father is, her miscarriage, her acquiescence towards selling her body in exchange for money and, ultimately, her murder). The narrative’s juxtaposition of ‘straight’ society with the behaviours and attitudes of permissive youth, gives it some similarity with Ross Macdonald’s later Lew Archer novels – which often saw private eye Archer investigating crimes involving ‘wayward’ young people who had strayed from the herd in terms of drugs or sexual promiscuity. This contrast between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ is also mirrored in Linda’s story. Bisexual and promiscuous, Linda is also deeply materialistic. Whilst the film attempts to present Linda as sympathetic, and Dalila di Lazzaro’s performance goes a long way in selling this, it’s difficult not to see the film as ‘punishing’ Linda for her ‘modern’ ways (through her pregnancy and her lack of certainty as to who the father is, her miscarriage, her acquiescence towards selling her body in exchange for money and, ultimately, her murder). The narrative’s juxtaposition of ‘straight’ society with the behaviours and attitudes of permissive youth, gives it some similarity with Ross Macdonald’s later Lew Archer novels – which often saw private eye Archer investigating crimes involving ‘wayward’ young people who had strayed from the herd in terms of drugs or sexual promiscuity.

In the sequence in which the corpse is preserved in formalin and put on display, like the real corpse at the centre of the 1934 case, La ragazza dal pigiama giallo offers a deeply mealy-mouthed critique of patriarchal voyeurism. Using a telephoto lens, the camera picks out the leering faces of the – mostly male – crowd that have gathered to see the naked corpse, the queue stretching into the distance. Some of the visitors try to take photographs of the body (but are stopped by the police), and others sneak furtive glances at its genitals. Thompson is critical of this idea (‘I suppose you’ll charge admission’, he says dryly when he first hears of the idea), and as Thompson is the guiding voice for much of the film, we share his cynicism; but the film is intent on having its cake and eating it, the camera caressing the naked female body on display – and later, when Linda is cajoled into selling herself in exchange for money, the film highlights the discomfort within this moment but, accompanied by Riz Ortolani’s pounding Moroder-esque disco score, it is presented as a subtly sleazy delight. An earlier scene seems metonymic of the film’s conflicted approach to this theme: when Thompson and Taylor question Quint after discovering that he was the one who dumped the cars on the beach, on his way out Thompson stops and stares at pages that Quint has torn out of a pornographic magazine and pasted to the walls of his workshop. Thompson’s fascination with these images is broken only when Taylor interrupts him and reminds Thompson that they must leave. As he exits, Thompson condescendingly tells Quint to ‘enjoy yourself’ and makes the sign for male masturbation. Like Thompson, the film criticises the male gaze whilst at the same time revelling in it.  The film arguably introduces one red herring too many with its subplot of a wealthy woman, Patricia Dorsey, who claims the corpse as being her daughter Anna – only for this to be revealed as an insurance scam (Patricia’s husband in a marriage-for-convenience took out a $100,000 insurance policy on Anna, at Patricia’s behest). Patricia’s husband is a stereotypically camp gay man, who lives in an apartment filled with caged birds where he is visited by a much younger lover, who married Patricia in order to get his ‘green card’. Although this subplot arguably points towards the film’s focus on the treatment of immigrants such as the Italian Antonio and the German Roy (interestingly, Roy is claimed to be Danish in the Italian version of the picture), not to mention the Canadian Thompson (named Timpson in the Italian version), it bloats the narrative, and its removal would take the film’s running time down to a lean 90 minutes or so – arguably resulting in a much tighter, more efficient story. The film arguably introduces one red herring too many with its subplot of a wealthy woman, Patricia Dorsey, who claims the corpse as being her daughter Anna – only for this to be revealed as an insurance scam (Patricia’s husband in a marriage-for-convenience took out a $100,000 insurance policy on Anna, at Patricia’s behest). Patricia’s husband is a stereotypically camp gay man, who lives in an apartment filled with caged birds where he is visited by a much younger lover, who married Patricia in order to get his ‘green card’. Although this subplot arguably points towards the film’s focus on the treatment of immigrants such as the Italian Antonio and the German Roy (interestingly, Roy is claimed to be Danish in the Italian version of the picture), not to mention the Canadian Thompson (named Timpson in the Italian version), it bloats the narrative, and its removal would take the film’s running time down to a lean 90 minutes or so – arguably resulting in a much tighter, more efficient story.

After the release of Mogherini’s film, a novel based on the screenplay was published in 1978. The novel was by Hugh Geddes (a pseudonym of the writer and filmmaker Hugh Atkinson) and titled The Pyjama Girl Case; Geddes’ adaptation emphasised the more sleazy elements of Mogherini’s film.

Video

Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and fills just over 28Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, with a running time of 102:08 mins. Presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and fills just over 28Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut, with a running time of 102:08 mins.

This presentation is billed as based on a 2k restoration from the original negative. For the most part, the film’s photography employs focal lengths within the ‘normal’ range. Detail is largely excellent, with a very pleasing level of fine detail being present within the image. A small handful of scenes seem to have been shot with a seemingly shonky zoom lens which seems to have produced/suffered with some sort of chromatic aberration (see the seventh of our full-sized screengrabs, at the bottom of this review). There is little damage other than some faint vertical lines that appear at the extreme right of the frame in a few scenes. Colours are rich and consistent: most of the film has a very naturalistic palette, but coloured gels (alternating green and red) are used in one sequence, and these primary colours are communicated with a strong sense of consistency. Contrast levels are very good, with defined midtones that display plenty of definition; moving into the shoulder, highlights are even, and there is some fine gradation into the shadows. Low light scenes far very well. Finally, a solid encode to disc retains the structure of 35mm film. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

The disc offers both (i) an English DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with accompanying optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing; and (ii) an Italian DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. In terms of range and fidelity, both tracks are pretty equal, offering good range and depth – though switching between the two there seems to be a slight difference in pitch/tone, and I wonder if one of the tracks has been pitch-corrected. The disc offers both (i) an English DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with accompanying optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing; and (ii) an Italian DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. In terms of range and fidelity, both tracks are pretty equal, offering good range and depth – though switching between the two there seems to be a slight difference in pitch/tone, and I wonder if one of the tracks has been pitch-corrected.

The English and Italian tracks are slightly different in places, including some of the character’s names (Professor Henry becomes Doctor Henry; Linda becomes Glenda; Buckingham becomes Nottingham) and histories (where Roy is identified as Danish in the English dialogue, he’s German in the Italian dialogue). Both tracks are post-synched, but the majority of the actors seem to have been speaking English on the set, and the Italian track loses Milland and Ferrer’s voices; but on the other hand, the Italian track is sometimes a little stronger, containing some slightly more profane dialogue in places and offering a more frank discussion of Linda/Glenda’s planned abortion.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with critic Troy Howarth. Critic Troy Howarth offers a discussion of the film that is packed with information about the various participants. Howarth’s appraisal of the film is balanced and acknowledges the picture’s weaknesses. - ‘Small World’ (28:30). Critic Michael Mackenzie reflects on the way in which examples of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (depending on your term of preference) explored themes of globalisation/internationalism – through the narratives of the films and the films’ status as international coproductions with cast members of various nationalities. - ‘A Good Bad Guy’ (31:46). A new interview with actor Howard Ross is included. Ross reflects on how he came to be involved in the film – and Mogherini’s insistence he play the ‘bad guy’ – and discusses his participation in it. He talks about his relationships with the other cast members, and he reflects on his relationship with his agent. Ross speaks in Italian; optional English subtitles are provided. - ‘A Study in Elegance’ (23:17). In a new interview, Alberto Tagliavia, the film’s editor, discusses his work on the picture. (Tagliavia was the editor on most of Mogherini’s pictures, so had a strong working relationship with the director.) Tagliavia reveals that, in his opinion, the plot of the picture ‘is not very special’, and consequently the film was edited and re-edited three times – the first time as a ‘straight’ giallo all’italiana, with the second and third edits changing the picture into a non-linear experience. Tagliavia speaks in Italian; optional English subtitles are included. - ‘Inside the Yellow Pyjama’ (15:04). In another new interview, the picture’s AD Feruccio Castronuovo, recollects working on the picture, which he describes as ‘a thriller with some pretty shocking scenes in it’. Castronuovo speaks in Italian; optional English subtitles are included. - ‘The Yellow Rhythm’ (21:24). Riz Ortolani speaks about his work as a composer of film scores, in an archival interview. Ortolani reflects on how he came to be a composer and discusses some of the films which he scored. Ortolani speaks in Italian; optional English subtitles are included. - Gallery (16 images). - Trailer (3:55).

Overall

The Pyjama Girl Case is an odd fish, coming towards the end of the popularity of the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana. It’s a film that has some interesting ideas, and its non-linear structure is, if not entirely innovative, certainly something that marks it as a fairly unique example of the Italian-style thriller; on the other hand, it’s a picture that feels very mealy-mouthed in its judgemental approach to the promiscuous and materialistic Linda, punishing her for her supposed transgressions, and criticising the exploitative ogling of the victim’s naked corpse whilst also hypocritically framing it as titillating. Speaking personally, when I was a 20-something fan of the thrilling all’italiana I first encountered The Pyjama Girl Case on videocassette in the 1990s, via its VHS release from Redemption/Salvation, and found the film difficult to warm to. Subsequent revisits via DVD and, now, Arrow’s Blu-ray release have consolidated my impression that the film is a good ten minutes too long and could be a much leaner, more efficient picture. The interview with Tagliavia on this disc, in which Tagliavia admits that the film’s plot ‘is not very special’ and so he was required to edit/re-edit the picture three times in an attempt to give it complexity or make it distinctive, points to weaknesses within the premise that the filmmakers attempted to address in postproduction. The cast is a clear strength, though the English dialogue is sometimes slightly awkward and comes across as stilted because of this. Nevertheless, it’s an entertaining picture which is, for the most part, very handsomely shot. The Pyjama Girl Case is an odd fish, coming towards the end of the popularity of the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana. It’s a film that has some interesting ideas, and its non-linear structure is, if not entirely innovative, certainly something that marks it as a fairly unique example of the Italian-style thriller; on the other hand, it’s a picture that feels very mealy-mouthed in its judgemental approach to the promiscuous and materialistic Linda, punishing her for her supposed transgressions, and criticising the exploitative ogling of the victim’s naked corpse whilst also hypocritically framing it as titillating. Speaking personally, when I was a 20-something fan of the thrilling all’italiana I first encountered The Pyjama Girl Case on videocassette in the 1990s, via its VHS release from Redemption/Salvation, and found the film difficult to warm to. Subsequent revisits via DVD and, now, Arrow’s Blu-ray release have consolidated my impression that the film is a good ten minutes too long and could be a much leaner, more efficient picture. The interview with Tagliavia on this disc, in which Tagliavia admits that the film’s plot ‘is not very special’ and so he was required to edit/re-edit the picture three times in an attempt to give it complexity or make it distinctive, points to weaknesses within the premise that the filmmakers attempted to address in postproduction. The cast is a clear strength, though the English dialogue is sometimes slightly awkward and comes across as stilted because of this. Nevertheless, it’s an entertaining picture which is, for the most part, very handsomely shot.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation of the film contains an excellent, very filmlike presentation of the main feature alongside an impressive array of contextual material. The interviews with the participants are most enlightening – particularly the interview with Tagliavia, the editor of the picture. Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|