|

|

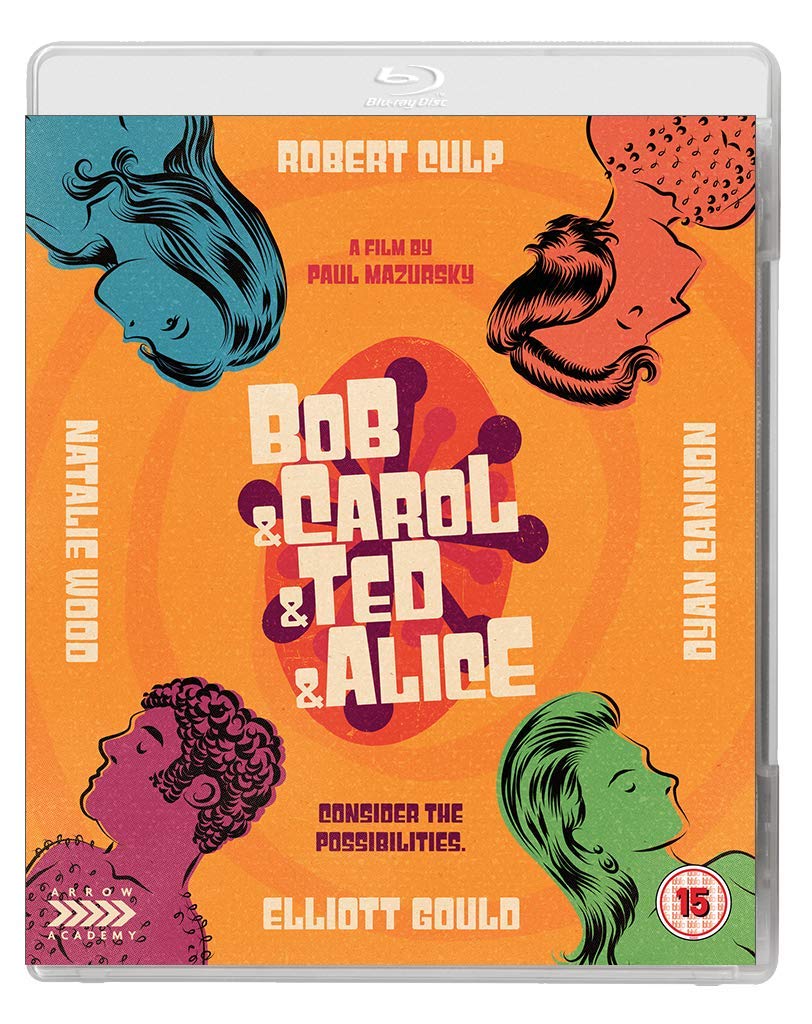

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd December 2018). |

|

The Film

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (Paul Mazursky, 1969) Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (Paul Mazursky, 1969)

Documentary filmmaker Bob (Robert Culp) and his wife Carol (Natalie Wood) journey to a retreat offering various psychotherapy sessions. Bob plans to make a documentary about the Institute. There, Bob and Carol take part in an ‘encounter’ group designed to encourage absolute honesty regarding the participants’ feelings. Bob finds his cynicism towards the Institute’s practices evaporating, and the experience brings him closer to Carol. Later, after returning home, Bob and Carol share their experiences at the Institute with their friends Ted (Elliott Gould) and Alice (Dyan Cannon), who gently mock the New Age values that Bob and Carol are now espousing. After a trip to San Francisco, where he has been working on the postproduction of a documentary, Bob reveals to Carol that whilst away from home, he had sex with a colleague. To Bob’s surprise, Carol isn’t angry but simply accepts Bob’s infidelity: ‘I don’t see how I can feel jealous about a purely physical thing you had with some dumb blonde’, she says, revealing that she ‘feel[s] closer to you than I’ve ever felt in my whole life’ thanks to Bob’s honesty about the situation.  Smoking pot with Ted and Alice after a party, Bob and Carol tell their friends about Bob’s act of infidelity. Alice is horrified, as much by Carol’s acceptance as by Bob’s actions in San Francisco; and Bob’s revelation continues to haunt her when the couple return home. She is so disgusted that she refuses to have sex with Ted, despite Ted’s comical attempts to seduce her. Smoking pot with Ted and Alice after a party, Bob and Carol tell their friends about Bob’s act of infidelity. Alice is horrified, as much by Carol’s acceptance as by Bob’s actions in San Francisco; and Bob’s revelation continues to haunt her when the couple return home. She is so disgusted that she refuses to have sex with Ted, despite Ted’s comical attempts to seduce her.

When Bob discovers that Carol is having a sexual relationship with her tennis coach, Horst (Hors Ebersberg), he is infuriated, though Carol reminds him that she accepted his infidelity without argument. Whilst in Las Vegas together, ostensibly to see Tony Bennett in concert, Driven by a variety of motivations, Bob, Carol, Ted and Alice decide to hold an impromptu orgy in one of the hotel rooms; but will this be a liberatory or destructive act – or a little of both at the same time?  Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice was the first feature film by its writer-director, Paul Mazursky, who had previously worked as a writer on television shows such as The Monkees (1966-8). Bob & Carol… was a notable critical and commercial success, its frank examination of sex and marriage becoming as iconic of the New Hollywood and the new era of liberation within cinema as John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (also 1969), Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde (1967) and Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970). As, during the late-1960s, the Production Code was phased out and replaced with a new age-based classification system, Hollywood films explored the boundaries of what was acceptable within mainstream cinema. With its exploration of the sexual freedoms associated with 1960s countercultures (including ‘swinging’ and open marriages), the ‘R’ rated Bob & Carol… felt very different to the pictures about marriage that had been made during the era of the Production Code, within which any discussion of sexual activity – either within the institution of marriage or outside it – was subject to very strict guidelines. Nevertheless, Bob & Carol is, aside from a few fleeting moments of nudity and some suggestive banter, far less explicit than audiences might have expected from a picture which featured on its poster the image of its four lead actors in bed together. However, the controversial decision to open the 1969 New York Film Festival with a screening of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice was a watershed moment, connecting the work of the New Hollywood filmmakers with those of the auteurs of European cinema whose work was featured in the same festival – such as Robert Bresson (Un femme douce), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Porcile) and Jean-Luc Godard (Le Gai Savoir). Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice was the first feature film by its writer-director, Paul Mazursky, who had previously worked as a writer on television shows such as The Monkees (1966-8). Bob & Carol… was a notable critical and commercial success, its frank examination of sex and marriage becoming as iconic of the New Hollywood and the new era of liberation within cinema as John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (also 1969), Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde (1967) and Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970). As, during the late-1960s, the Production Code was phased out and replaced with a new age-based classification system, Hollywood films explored the boundaries of what was acceptable within mainstream cinema. With its exploration of the sexual freedoms associated with 1960s countercultures (including ‘swinging’ and open marriages), the ‘R’ rated Bob & Carol… felt very different to the pictures about marriage that had been made during the era of the Production Code, within which any discussion of sexual activity – either within the institution of marriage or outside it – was subject to very strict guidelines. Nevertheless, Bob & Carol is, aside from a few fleeting moments of nudity and some suggestive banter, far less explicit than audiences might have expected from a picture which featured on its poster the image of its four lead actors in bed together. However, the controversial decision to open the 1969 New York Film Festival with a screening of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice was a watershed moment, connecting the work of the New Hollywood filmmakers with those of the auteurs of European cinema whose work was featured in the same festival – such as Robert Bresson (Un femme douce), Pier Paolo Pasolini (Porcile) and Jean-Luc Godard (Le Gai Savoir).

David Desser & Lester D Friedman suggest that the tag line for Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, ‘Consider the Possibilities’, is ‘an apt one-line summary of all [director Paul] Mazursky’s subsequent features’ (Desser & Friedman, 2004: 240). The possibilities offered to the characters in Mazursky’s films – especially Bob & Carol… - are simultaneously ‘an invitation […]; a warning […]; a dare […]; and a directive’, and Mazursky’s characters are placed in situations in which they must look at their lives and reflect on alternatives (ibid.) The film’s opening sequence, which cross-cuts Bob and Carol’s journey to the Institute with images from inside it (a ‘primal therapy’ session; a Tai-Chi class; naked figures in a spa), connects these activities with an existential search for meaning by accompanying this footage on the soundtrack with the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ from Handel’s Messiah. The groups at the Institute, including an ‘encounter’ group in which the participants share their feelings and gaze into one another’s eyes, are ‘alternative’ and designed as a form of psychotherapy. For their participants, this search for meaning takes many different forms: at the encounter group, where the participants are asked to explain why they are at the retreat, an older man, Conrad (John Halloran), states that ‘I am 64 years and I want to continue to grow as a person’; by contrast, a woman, Myrna (Diane Berghoff), declares simply that ‘I came here because I want a better orgasm’. David Desser & Lester D Friedman suggest that the tag line for Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, ‘Consider the Possibilities’, is ‘an apt one-line summary of all [director Paul] Mazursky’s subsequent features’ (Desser & Friedman, 2004: 240). The possibilities offered to the characters in Mazursky’s films – especially Bob & Carol… - are simultaneously ‘an invitation […]; a warning […]; a dare […]; and a directive’, and Mazursky’s characters are placed in situations in which they must look at their lives and reflect on alternatives (ibid.) The film’s opening sequence, which cross-cuts Bob and Carol’s journey to the Institute with images from inside it (a ‘primal therapy’ session; a Tai-Chi class; naked figures in a spa), connects these activities with an existential search for meaning by accompanying this footage on the soundtrack with the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ from Handel’s Messiah. The groups at the Institute, including an ‘encounter’ group in which the participants share their feelings and gaze into one another’s eyes, are ‘alternative’ and designed as a form of psychotherapy. For their participants, this search for meaning takes many different forms: at the encounter group, where the participants are asked to explain why they are at the retreat, an older man, Conrad (John Halloran), states that ‘I am 64 years and I want to continue to grow as a person’; by contrast, a woman, Myrna (Diane Berghoff), declares simply that ‘I came here because I want a better orgasm’.

As the film opens, it is clear that Carol defines herself through her relationship with Bob, telling the members of the encounter group that she is at the Institute simply because Bob is there. (‘I’m Carol. I’m Bob’s wife, and I came here because Bob came’.) However, as the film progresses Carol finds, through her changing relationship with Bob, a sense of emancipation – firstly by ‘accepting’ the extramarital sex that Bob confesses to having engaged in during his trip to San Francisco, and secondly by seeking her own extramarital sexual pleasure through her relationship with the tennis coach Horst. (Bob’s hysterical reaction to this highlights his hypocrisy.) For Carol, the sexual freedoms offered by the ideas she encounters within the retreat seem genuinely to offer her a form of liberation from her role as ‘Bob’s wife’.  One of the deepest ironies within the film is that Bob and Carol’s project of sexual liberation, which eventually swamps both their lives and the lives of their friends Ted and Alice, arises because Bob, a documentary filmmaker, cannot maintain a sense of objectivity in relation to the subject of his planned documentary (which is the retreat to which he and Carol journey in the film’s opening sequence). Speaking as a practised documentarist myself (one of my other hats is as a published and exhibited documentary photographer), I can sympathise with the difficulty Bob experiences in maintaining his objectivity and allowing his attitudes to become directed by his subject. However, Bob ironically demonstrates a profound sense of objectivity in completely inappropriate contexts: for example, at his little boy’s birthday party, Bob perches a good distance away from his own child and records the events on a 16mm camera, seeming to be completely disengaged from the family gathering that is taking place in front of his camera lens. Interestingly, Mazursky himself maintains a sense of objectivity towards the countercultural values to which Bob and Carol aspire, neither openly celebrating them or condemning them: as John Simon noted, Bob & Carol… may be read ‘as a daring comedy essentially affirming the sexual revolution, or as a daring comedy essentially satirizing’ it (Simon, quoted in Delgaudio, 1992: 185). One of the deepest ironies within the film is that Bob and Carol’s project of sexual liberation, which eventually swamps both their lives and the lives of their friends Ted and Alice, arises because Bob, a documentary filmmaker, cannot maintain a sense of objectivity in relation to the subject of his planned documentary (which is the retreat to which he and Carol journey in the film’s opening sequence). Speaking as a practised documentarist myself (one of my other hats is as a published and exhibited documentary photographer), I can sympathise with the difficulty Bob experiences in maintaining his objectivity and allowing his attitudes to become directed by his subject. However, Bob ironically demonstrates a profound sense of objectivity in completely inappropriate contexts: for example, at his little boy’s birthday party, Bob perches a good distance away from his own child and records the events on a 16mm camera, seeming to be completely disengaged from the family gathering that is taking place in front of his camera lens. Interestingly, Mazursky himself maintains a sense of objectivity towards the countercultural values to which Bob and Carol aspire, neither openly celebrating them or condemning them: as John Simon noted, Bob & Carol… may be read ‘as a daring comedy essentially affirming the sexual revolution, or as a daring comedy essentially satirizing’ it (Simon, quoted in Delgaudio, 1992: 185).

Ultimately, Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice are tourists within the counterculture, middle-aged and middle-class outsiders tasting the forbidden fruit of hedonistic youth. When Bob and Carol try to take the values they have internalised at the Institute into the outside world, we see how incongruous these values are. At a restaurant, Carol challenges their waiter, Emilio (Lee Bergere), when he tells them ‘I hope everything was satisfactory’. ‘Do you really, Emilio?’, Carol interrogates him, ‘Is that what you really feel?’ This moment comes shortly after Bob has told Ted and Alice that ‘The truth is always beautiful’: the film reminds us subtly of the manner in which deceptions – both big and little – are, within everyday life, utterly necessary. With his hippy beads and long hair (the butt of a joke between the main characters), Bob – essayed by then-39 year old Robert Culp – is ultimately a pathetic character, a man who becomes hypocritically petulant when his wife samples the illicit pleasures of extramarital sex that he himself has already enjoyed. For his part, Ted looks absurdly out of place when the climactic orgy begins in the Las Vegas hotel: dressed only in his white Y-fronts, Ted preens himself in the mirror whilst Bob and Carol and Alice begin their adventures on the hotel bed; when Ted enters the room, he quietly slips beneath the sheets next to Carol, who urges him to remove his underwear. Visibly embarrassed, Ted concedes to her demand; but he looks the figure of awkwardness as he does so. As Sybil Delgaudio notes, the characters in the film try out ‘the counterculture as they would the latest fashions’, and their ‘attempts at progressivism are often overreactions to their own discomfort’ (Delgaudio, op cit.: 186). Their experiments with sexual liberation do not provide them with the personal liberation they seek: Tamar Jeffers McDonald notes that Bob, Carol, Ted and Alice’s ‘adoption of trendy free love teachings and a doctrine of total honesty about sexual matters complicates their lives rather than freeing them from false ideologies’ (McDonald, 2007: 56). Ultimately, Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice are tourists within the counterculture, middle-aged and middle-class outsiders tasting the forbidden fruit of hedonistic youth. When Bob and Carol try to take the values they have internalised at the Institute into the outside world, we see how incongruous these values are. At a restaurant, Carol challenges their waiter, Emilio (Lee Bergere), when he tells them ‘I hope everything was satisfactory’. ‘Do you really, Emilio?’, Carol interrogates him, ‘Is that what you really feel?’ This moment comes shortly after Bob has told Ted and Alice that ‘The truth is always beautiful’: the film reminds us subtly of the manner in which deceptions – both big and little – are, within everyday life, utterly necessary. With his hippy beads and long hair (the butt of a joke between the main characters), Bob – essayed by then-39 year old Robert Culp – is ultimately a pathetic character, a man who becomes hypocritically petulant when his wife samples the illicit pleasures of extramarital sex that he himself has already enjoyed. For his part, Ted looks absurdly out of place when the climactic orgy begins in the Las Vegas hotel: dressed only in his white Y-fronts, Ted preens himself in the mirror whilst Bob and Carol and Alice begin their adventures on the hotel bed; when Ted enters the room, he quietly slips beneath the sheets next to Carol, who urges him to remove his underwear. Visibly embarrassed, Ted concedes to her demand; but he looks the figure of awkwardness as he does so. As Sybil Delgaudio notes, the characters in the film try out ‘the counterculture as they would the latest fashions’, and their ‘attempts at progressivism are often overreactions to their own discomfort’ (Delgaudio, op cit.: 186). Their experiments with sexual liberation do not provide them with the personal liberation they seek: Tamar Jeffers McDonald notes that Bob, Carol, Ted and Alice’s ‘adoption of trendy free love teachings and a doctrine of total honesty about sexual matters complicates their lives rather than freeing them from false ideologies’ (McDonald, 2007: 56).

Much play is made of the frustrated attempts of husbands to seduce their wives and the confusion of sexual desire and love. One of the film’s pivotal scenes involves Ted trying to make love to his wife Alice, who is so disgusted with Bob’s infidelity that she cannot bear her husband’s touch. In one of the film’s most darkly funny scenes, Alice visits her psychiatrist and discusses her lack of libido. The psychiatrist in this scene is played by Donald F Muhich, himself a real psychiatrist for a number of years; Muhich played similar roles in several other films by Mazursky. Muhich gives the character a strange tic (pulling on his cheek) as he listens earnestly to Alice, the film intercutting her almost hysterical rambling about sex and her marriage with the psychiatrist’s relaxed, disengaged behaviour; he listens patiently to Alice’s discussion of her sex life (or lack thereof) and corrects her evasive language (when Alice refers to her genitals using a childish euphemism, he psychiatrist reminds her that she is referring to her vagina). Ultimately, as Tim, the leader of the encounter group at the Institute, says: ‘We talk a lot about love, but we don’t feel it a lot’

Video

Taking up a little under 30Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. Shot on 35mm colour stock, Bob & Carol… is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 105:27 mins. There is some beautiful, stately photography in many of the film’s scenes – in the opening sequence, for example, the camera picks out the shadows of the members of the Tai Chi class at the Institute – but dialogue scenes are, for the most part, photographed quite ‘flatly’ though sometimes livened up by bits of business from the actors (eg, Elliott Gould’s tendency to dance to/with himself in the background). Taking up a little under 30Gb of space on a dual layered Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. Shot on 35mm colour stock, Bob & Carol… is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 105:27 mins. There is some beautiful, stately photography in many of the film’s scenes – in the opening sequence, for example, the camera picks out the shadows of the members of the Tai Chi class at the Institute – but dialogue scenes are, for the most part, photographed quite ‘flatly’ though sometimes livened up by bits of business from the actors (eg, Elliott Gould’s tendency to dance to/with himself in the background).

Working with a master provided by Sony (which is taken from unspecified materials), the presentation is very pleasing, offering a rich level of detail within the image. Fine detail is present in close-ups. Damage is negligible though there are one or two fleeting shots that look to have been affected by moisture damage or something similar. Contrast levels are excellent, with rich and defined midtones tapering off and offering balanced gradation into the toe. Highlights are equally balanced. Colours are naturalistic and consistent, and the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, which is carried through a solid encode to disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is rich and clear, offering good range. The audio track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, which are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc contains: The disc contains:

- An audio commentary with Paul Mazursky, Robert Culp, Dyan Cannon and Elliott Gould. Recorded for a prior DVD release, this commentary track is filled with vivid recollections from the director and then-surviving members of the principal cast. (Of course, Robert Culp has since passed away.) The participants are in good humour throughout, praising the sense of ‘reality’ within Mazursky’s filmmaking technique in particular. Mazursky reflects on the origins of the story and talks about some technical aspects of the production – in particular, the photography. They also talk about the reception which greeted the picture. - An audio commentary with film scholar Adrian Martin. Adrian Martin, the Australian film critic, offers a commentary track which is dense with content. Martin offers some interesting critical insight into the picture and demonstrates plenty of research in his discussion of the making of the picture. He talks about the film’s ironic approach to ‘the birth of the New Age movement’ but also highlights the film’s ‘satirical eye’ towards ‘these new developments in society’. - ‘Bob & Natalie & Elliott & Dyan… & Paul (19:27). In this video essay, film critic David Cairns discusses the picture and talks about its relationship with US culture of the late 1960s. Cairns reflects on Mazursky’s approach to the material, talking about the fallout from Mazursky’s encounter with Peter Sellers (who claimed Mazursky had had an affair with Sellers’ then-new wife Britt Ekland) – which preceded Mazursky’s debut feature and may have impacted on the film’s themes. (The eagle eyed will notice that Elliott Gould’s forename is misspelled in the title of the featurette as presented on the disc menu, though not on the titles of the featurette itself.) - ‘Tales of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (17:46)’. In this interview from 2003, recorded on stage at the Lee Strasberg Theater Institute, Mazurksy speaks about his work as a filmmaker. He talks about the evolution of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and how he managed to get the script accepted by a studio. He also discusses the film’s approach to New Age beliefs and reflects on his work with the actors.

Overall

Emblematic of a watershed moment in mainstream American cinema, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice feels rather ‘tame’ today and, unlike some other examples of the New Hollywood cinema, has arguably lost some of its bite. On the other hand, what the film has to say about the relationship between sex and love – especially in the half decade or so that has passed since the ‘sexual revolution’ – is arguably just as relevant to modern audiences. Regardless, it’s a very humanistic picture, Mazursky handling the material in a subtle and objective way – which closes with a sequence which pays more than a nod to the work of Federico Fellini. The film is also enlivened by some excellent performances, especially from Natalie Wood and Elliott Gould. Emblematic of a watershed moment in mainstream American cinema, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice feels rather ‘tame’ today and, unlike some other examples of the New Hollywood cinema, has arguably lost some of its bite. On the other hand, what the film has to say about the relationship between sex and love – especially in the half decade or so that has passed since the ‘sexual revolution’ – is arguably just as relevant to modern audiences. Regardless, it’s a very humanistic picture, Mazursky handling the material in a subtle and objective way – which closes with a sequence which pays more than a nod to the work of Federico Fellini. The film is also enlivened by some excellent performances, especially from Natalie Wood and Elliott Gould.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice offers a very pleasing presentation of the main feature that is supported by some very good contextual material. Fans of the film will find this release a worthy purchase. Reference: Delgaudio, Sybil, 1992: ‘Columbia and the Counterculture: Trilogy of Defeat’. In: Dick, Bernard F (ed), 1992: Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio. The University Press of Kentucky: 182-90 Desser, David & Friedman, Lester D, 2004: American Jewish Filmmakers. University of Illinois Press (Second Edition) McDonald, Tamar Jeffers, 2007: Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. London: Wallflower Press Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|