|

|

The Film

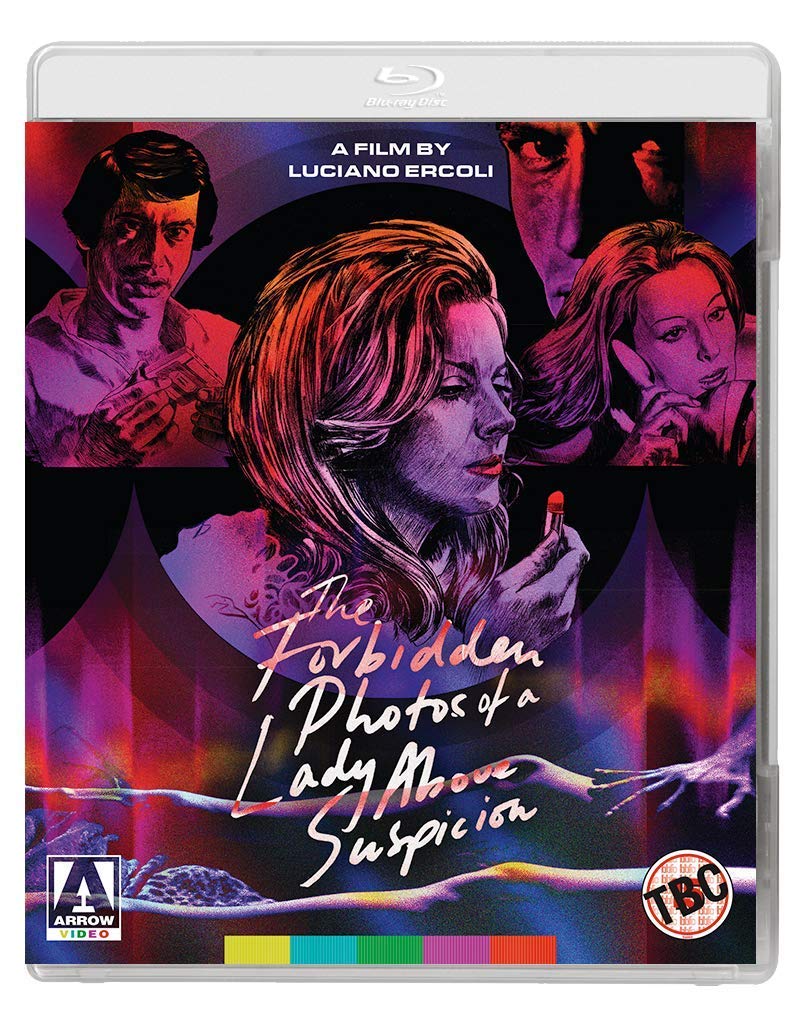

Le foto proibite di una signora per bene / Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion (Luciano Ercoli, 1970) Le foto proibite di una signora per bene / Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion (Luciano Ercoli, 1970)

Bored bourgeois housewife Minou (Dagmar Lassander) lives on a diet of booze and prescription medication. She dreams up scenarios of seducing her apparently frigid husband Pier (Pier Paolo Capponi) by making him jealous. One evening, this neglected and unsatisfied woman ventures out to meet her husband but is accosted on a beach by a man (Simon Andreu) who uses a flick-knife to cut the straps from her dress, exposing her breasts, before telling her that her husband is a murderer. Minou learns from her sexually liberated friend Dominique (Nieves Navarro/Susan Scott), who incidentally used to be Pier’s lover, that one of the creditors of Pier’s company, Jean Dubois, was found dead on the beach. Later, Pier tells Minou that Dubois died ‘at the right moment’: Dubois had just given Pier’s company, which is struggling financially, a large loan. Minou also discovers that the cause of Dubois’ death was an embolism as a result of aerobullosis (decompression sickness), and Pier’s company’s latest project is a new design for a decompression chamber. Minou soon receives a telephone call from her attacker, demanding that Minou meet him at a specific address and playing part of an audio recording that implicates Pier in the murder of Dubois. There, Minou confronts the man, offering him money in exchange for the recording of Pier plotting Dubois’ death. However, the man turns down the offer of money, suggesting instead that he wants Minou to sleep with him – or rather, to beg him to sleep with her. Minou agrees. However, later the man attempts to blackmail her further, with photographs of their liaison.  Minou contemplates suicide but instead decides to come clean with Pier. Together, they enlist the help of a police commissioner, Franco (Osvaldo Genezzani). Franco gets access to the address to which Minou was sent, but they discover that the apartment is empty – and has apparently been vacant for some time. Has Minou dreamt up the whole scenario or is there a conspiracy against her? Minou contemplates suicide but instead decides to come clean with Pier. Together, they enlist the help of a police commissioner, Franco (Osvaldo Genezzani). Franco gets access to the address to which Minou was sent, but they discover that the apartment is empty – and has apparently been vacant for some time. Has Minou dreamt up the whole scenario or is there a conspiracy against her?

Notoriously difficult to pin down, the thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller, or giallo all’italiana) is remarkably diverse; this is something that is sometimes sidelined in the the fan discourse that surrounds Italian thrillers in English-language circles. The boom period of the Italian thrilling/giallo pictures is usually cited as taking place between the mid-1960s (and often claimed to be sparked by Mario Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino/Blood and Black Lace in 1964) and mid/late-1980s, when the popularity of the thrilling all’italiana began to decline amongst domestic audiences. During this time, a wide variety of thrillers were defined by the curious flavour or ‘Italian-style’ that the name of this subgroup of films suggests, in a similar way to the roughly contemporaneous western all’italiana (Italian-style Western) and poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police picture). Much as fans have embraced and come to use the originally pejorative label ‘Spaghetti Western’ to denote the western all’italiana (and the equally pejorative poliziotteschi to denote the poliziesco all’italiana), English-speaking fans of the thrilling all’italiana have demonstrated a tendency to employ the label giallo to denote these Italian-made thrillers of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. However, in truth, to Italian audiences a giallo is simply a thriller of any origin, and Italian cinephiles may apply the label may as much to a film such as John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) as to Italian thrillers such as Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino. As Philippe Met suggests, approaches to understanding the giallo/thrilling all’italiana are complicated by ‘existing discrepancies of a semantic or taxonomic nature’ (2006: 196). Met suggests that there is irony within the fact that within Italy, ‘in the very country in which it [the giallo/thrilling all’italiana] originated, the all’italiana [Italian-style] specificity of the genre’ is largely ‘subsumed by […] a much broader understanding of the giallo designation as coextensive with crime cinema’ more generally, ‘cutting across national boundaries and the typological spectrum’; whilst in Britain and America, on the other hand, the giallo is seen as an exclusively Italian product, to the extent that debates exist as to whether ‘one can viably and legitimately stretch it to create an “American giallo”’, for example (ibid.). Thus it is impossible to overstate how significant the ‘Italian-style’ of the Italian-language designator (thrilling all’italiana, or sometimes giallo all’italiana) is.  The exact constituents of this ‘Italian-style’, however, are as difficult to determine, and as debatable, as the qualities which are seen to make a 1940s or 1950s thriller a film noir. The Italian thrillers themselves include Edgar Wallace adaptations (Massimo Dallamano’s Cosa avete fatto a Solange?/ What Have You Done to Solange?, 1972), paranoid political thrillers (La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films). The exact constituents of this ‘Italian-style’, however, are as difficult to determine, and as debatable, as the qualities which are seen to make a 1940s or 1950s thriller a film noir. The Italian thrillers themselves include Edgar Wallace adaptations (Massimo Dallamano’s Cosa avete fatto a Solange?/ What Have You Done to Solange?, 1972), paranoid political thrillers (La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films).

In reference to Le foto proibite di una signora per bene, the first thrilling all’italiana by director Luciano Ercoli (who would go on to make a number of thrillers in subsequent years), Mikel Koven has allied the picture with a group of examples of the Italian thriller that, unusually, revolve around neither an Agatha Christie-esque amateur detective nor a member of the police force (Koven, 2006: 8). These films feature plots which ‘are more akin to suspense thrillers’ than the more dominant forms of Italian thriller of the period (ibid.). Koven cites Charles Derry’s definition of a suspense thriller as a narrative that features a murderous antagonist pursuing ‘either an innocent victim or a non-professional criminal’ in a context which avoids emphasising ‘a traditional figure of detection’ such as an amateur sleuth or a police detective (Derry, quoted in ibid.). Like other examples of the suspense thriller within the thrilling all’italiana, such as Enzo Castellari’s Gli occhi fredda della paura (Cold Eyes of Fear, 1971) and Aldo Lado’s L’Ultimo treno della note (Late Night Trains/Night Train Murders, 1975), Koven argues that Ercoli’s picture features a small handful of locations – with its story predominantly focused on domestic spaces (ibid.). The distinction is similar to that within the world of film noir, between the more action-oriented private eye-focused picture like The Maltese Falcon and the quieter, more Gothic melodramas such as Fritz Lang’s The Secret Beyond the Door (1947).  Though it is female-focused and, like The Secret Beyond the Door, has a relationship with the French folktale of Bluebeard, Le foto proibite… has been cited by Kier-La Janisse as ‘revel[ling] in potentially offensive gender politics’ (La-Janisse, 2012: np). This is presumably owing to its depiction of Minou as a woman who, from the outset, is codified as vain and shallow. In the film’s opening sequence, Minou is shown in the bath, her face caked in makeup (later in the film, she takes another bath with her makeup visibly intact, and she also goes to bed in her makeup – which is remarkably fresh when she wakes up in the morning) as, via an offscreen voiceover, she plans ways of seducing Pier. ‘When you return tomorrow night, I won’t let you make love with me right away’, she narrates dreamily as she gazes narcissistically into a mirror, ‘I’ll tell you that I’m in love with someone else, that we have to get a divorce but we could still be friends. Then, after you make a terrible scene…’ A woman who is eager to exploit her sexuality and provoke jealousy in order to pique the interest of her sexually disinterested husband, Minou drinks and abuses prescription medication (presumably sedatives of some kind). She makes empty promises to change her lifestyle in order to satisfy the man in her life, narrating that ‘Today I will give up cigarettes. I will neither drink whisky nor take those pills. They say it’s bad for you to take both at the same time. That should make Pier happy’. However, as the narrative progresses it becomes clear that Minou has not followed through with any of the promises she made in the film’s opening narration. (The banality of her voiceover might remind the viewer of Bret Easton Ellis’ satirically deadpan adoption of the ‘flat’ language of the privileged in his 1980s novels – most memorably, American Psycho in 1989.) Her drinking and pill-popping contribute to the sense developed throughout the story that her perspective on the narrative may not be wholly reliable. Though it is female-focused and, like The Secret Beyond the Door, has a relationship with the French folktale of Bluebeard, Le foto proibite… has been cited by Kier-La Janisse as ‘revel[ling] in potentially offensive gender politics’ (La-Janisse, 2012: np). This is presumably owing to its depiction of Minou as a woman who, from the outset, is codified as vain and shallow. In the film’s opening sequence, Minou is shown in the bath, her face caked in makeup (later in the film, she takes another bath with her makeup visibly intact, and she also goes to bed in her makeup – which is remarkably fresh when she wakes up in the morning) as, via an offscreen voiceover, she plans ways of seducing Pier. ‘When you return tomorrow night, I won’t let you make love with me right away’, she narrates dreamily as she gazes narcissistically into a mirror, ‘I’ll tell you that I’m in love with someone else, that we have to get a divorce but we could still be friends. Then, after you make a terrible scene…’ A woman who is eager to exploit her sexuality and provoke jealousy in order to pique the interest of her sexually disinterested husband, Minou drinks and abuses prescription medication (presumably sedatives of some kind). She makes empty promises to change her lifestyle in order to satisfy the man in her life, narrating that ‘Today I will give up cigarettes. I will neither drink whisky nor take those pills. They say it’s bad for you to take both at the same time. That should make Pier happy’. However, as the narrative progresses it becomes clear that Minou has not followed through with any of the promises she made in the film’s opening narration. (The banality of her voiceover might remind the viewer of Bret Easton Ellis’ satirically deadpan adoption of the ‘flat’ language of the privileged in his 1980s novels – most memorably, American Psycho in 1989.) Her drinking and pill-popping contribute to the sense developed throughout the story that her perspective on the narrative may not be wholly reliable.

As the plot against her seems to escalate, Minou is seen by the other characters as less and less reliable – and even the film’s viewer might begin to question her reliability when, upon investigation by Franco, it seems the rooms in which she meets her blackmailer are revealed to be empty, apparently having been unlived-in for some time. (‘This place looks like it was abandoned a century ago’, Franco notes.) The viewer begins to ask: has Minou dreamt up the whole scenario? This sense of a character whose fantasies of persecution may or may not be delusional bears some comparison with the ambiguities of the conspiracies depicted in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1965) and Richard C Sarafian’s Fragment of Fear (also 1970), which prefigured Dario Argento’s use of the lead actor in both of those films, David Hemmings, in his thrilling all’italiana Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1974) – a picture that arguably reverses the gender roles normally encountered in examples of the suspense thriller (as outlined by Mikel Koven, above). As the plot against her seems to escalate, Minou is seen by the other characters as less and less reliable – and even the film’s viewer might begin to question her reliability when, upon investigation by Franco, it seems the rooms in which she meets her blackmailer are revealed to be empty, apparently having been unlived-in for some time. (‘This place looks like it was abandoned a century ago’, Franco notes.) The viewer begins to ask: has Minou dreamt up the whole scenario? This sense of a character whose fantasies of persecution may or may not be delusional bears some comparison with the ambiguities of the conspiracies depicted in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1965) and Richard C Sarafian’s Fragment of Fear (also 1970), which prefigured Dario Argento’s use of the lead actor in both of those films, David Hemmings, in his thrilling all’italiana Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1974) – a picture that arguably reverses the gender roles normally encountered in examples of the suspense thriller (as outlined by Mikel Koven, above).

Le foto proibite… makes no bones about its focus on the conflict between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’. After the bourgeois Minou is attacked on the beach, she seeks refuge in a café where she sits down at a table with a couple of deeply proletarian men. There are uneasy glances between these two very different social groups, their seemingly unsurmountable cultural differences emphasised through their respective costumes. Later, when the blackmailer tells Minou to meet him at an address in the city, the address leads Minou to a dingy, proletarian flat; and when Minou offers her attacker money in exchange for the audio recording that implicates Pier in the murder of Dubois, she is astonished when he tells her ‘You don’t have any power over me. You just have a few coloured papers [banknotes]’. Framed in this way, Minou’s blackmailer’s assault on her comfortable middle-class existence seems like an example of class warfare, especially when the blackmailer takes such obvious delight in humiliating Minou by stripping her of her fine clothes – and her sense of propriety – and degrading her through pressuring her into demanding intercourse with him. When Minou is attacked on the beach in the film’s opening sequences, her attacker tells her that ‘I’m not going to force you. You’re going to have to beg me. You’ll be begging me to take you’, before teasing her with the blade of his knife. (‘I’m the master of your soul and your body’, he tells her much later in the film, ‘I want what I like and I will take it. Life is for pleasure [….] You have to beg for my touch. Like a slave; like a whore’.) Minou struggles to devise a method by which to stop her blackmailer, who like a true revolutionary is uninterested in money: ‘He’s only interested in this madness’, Minou tells Dominique, adding later that ‘This man is insane. He doesn’t think like others do. Nobody can predict what he’ll do next’. In response, Dominique allows Minou access to her private philosophy: ‘Everything has a price, even madness’. When Minou first tells Dominique of her assault on the beach, Dominique suggests that she would have found the situation stimulating – before going on to show Minou her collection of pornographic photographs, taking delight in Minou’s subtle discomfort with such imagery. (It is in one of these photographs, which Dominique bought in Copenhagen, that Minou recognises her attacker.) Le foto proibite… makes no bones about its focus on the conflict between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’. After the bourgeois Minou is attacked on the beach, she seeks refuge in a café where she sits down at a table with a couple of deeply proletarian men. There are uneasy glances between these two very different social groups, their seemingly unsurmountable cultural differences emphasised through their respective costumes. Later, when the blackmailer tells Minou to meet him at an address in the city, the address leads Minou to a dingy, proletarian flat; and when Minou offers her attacker money in exchange for the audio recording that implicates Pier in the murder of Dubois, she is astonished when he tells her ‘You don’t have any power over me. You just have a few coloured papers [banknotes]’. Framed in this way, Minou’s blackmailer’s assault on her comfortable middle-class existence seems like an example of class warfare, especially when the blackmailer takes such obvious delight in humiliating Minou by stripping her of her fine clothes – and her sense of propriety – and degrading her through pressuring her into demanding intercourse with him. When Minou is attacked on the beach in the film’s opening sequences, her attacker tells her that ‘I’m not going to force you. You’re going to have to beg me. You’ll be begging me to take you’, before teasing her with the blade of his knife. (‘I’m the master of your soul and your body’, he tells her much later in the film, ‘I want what I like and I will take it. Life is for pleasure [….] You have to beg for my touch. Like a slave; like a whore’.) Minou struggles to devise a method by which to stop her blackmailer, who like a true revolutionary is uninterested in money: ‘He’s only interested in this madness’, Minou tells Dominique, adding later that ‘This man is insane. He doesn’t think like others do. Nobody can predict what he’ll do next’. In response, Dominique allows Minou access to her private philosophy: ‘Everything has a price, even madness’. When Minou first tells Dominique of her assault on the beach, Dominique suggests that she would have found the situation stimulating – before going on to show Minou her collection of pornographic photographs, taking delight in Minou’s subtle discomfort with such imagery. (It is in one of these photographs, which Dominique bought in Copenhagen, that Minou recognises her attacker.)

When Minou is blackmailed into sleeping with the man who has been stalking her, afterwards she displays a profound ambivalence towards the act: the mild sadomasochistic play in which he has forced her to participate apparently kindles a sexual desire that has remained dormant in her relationship with her seemingly frigid husband. Minou returns to this moment time and time again, through small, brief flashbacks; the dialogue suggests that Minou finds this new relationship, in which she is profoundly submissive, stimulating and sexually exciting. ‘You had a more erotic adventure than usual’, Dominique tells Minou, ‘and you enjoyed it’. Concurrently, Minou begins to doubt her relationship with her husband, admitting that she ‘believed him [the blackmailer] right away [that Pier is a killer]’, though Pier never seems to question her: Danny Shipka has argued that the overriding theme of Le foto proibite… and Ercoli’s other thrilling all’italiana films (La morte cammina con i tacchi alti/Death Walks in High Heels, 1971 and La morte accarezza a mezzanotte/Death Walks at Midnight, 1972) is ‘the deceptive relationships between heterosexual spouses and lovers’, focusing on ‘the nightmare of being threatened by one’s own sexual partner’ (Shipka, 2011: 93). Shipka suggests that Ercoli’s thrillers are fascinated with the notion of ‘[d]eception from men’ and, in contrast to La-Janisse, Shipka argues that Ercoli’s thrillers feature ‘strong female characters’ (ibid.). In Le foto proibite…, Nieves Navarro (Susan Scott) – who in 1972 would marry Ercoli – essays the role of the ‘sexually liberated, intelligent Dominique’, a character who is ‘neither a victim nor a villain but an intelligent, sexually strong character who manages to figure out the plot and diffuses it’ (ibid.). ‘As long as it gives me pleasure’, Dominique tells Minou when Minou queries Dominique’s collection of pornographic photographs, and it seems that the film narrativises Minou’s potentially dangerous search for something that ‘gives [her] pleasure’. Ultimately, Le foto proibite… could be said to be a picture about what J G Ballard called the ‘death of affect’ – overstimulation amongst the bourgeoisie and a resultant flattening of emotion – and Minou’s search for some form of stimulation which will provoke an emotional response. When Minou is blackmailed into sleeping with the man who has been stalking her, afterwards she displays a profound ambivalence towards the act: the mild sadomasochistic play in which he has forced her to participate apparently kindles a sexual desire that has remained dormant in her relationship with her seemingly frigid husband. Minou returns to this moment time and time again, through small, brief flashbacks; the dialogue suggests that Minou finds this new relationship, in which she is profoundly submissive, stimulating and sexually exciting. ‘You had a more erotic adventure than usual’, Dominique tells Minou, ‘and you enjoyed it’. Concurrently, Minou begins to doubt her relationship with her husband, admitting that she ‘believed him [the blackmailer] right away [that Pier is a killer]’, though Pier never seems to question her: Danny Shipka has argued that the overriding theme of Le foto proibite… and Ercoli’s other thrilling all’italiana films (La morte cammina con i tacchi alti/Death Walks in High Heels, 1971 and La morte accarezza a mezzanotte/Death Walks at Midnight, 1972) is ‘the deceptive relationships between heterosexual spouses and lovers’, focusing on ‘the nightmare of being threatened by one’s own sexual partner’ (Shipka, 2011: 93). Shipka suggests that Ercoli’s thrillers are fascinated with the notion of ‘[d]eception from men’ and, in contrast to La-Janisse, Shipka argues that Ercoli’s thrillers feature ‘strong female characters’ (ibid.). In Le foto proibite…, Nieves Navarro (Susan Scott) – who in 1972 would marry Ercoli – essays the role of the ‘sexually liberated, intelligent Dominique’, a character who is ‘neither a victim nor a villain but an intelligent, sexually strong character who manages to figure out the plot and diffuses it’ (ibid.). ‘As long as it gives me pleasure’, Dominique tells Minou when Minou queries Dominique’s collection of pornographic photographs, and it seems that the film narrativises Minou’s potentially dangerous search for something that ‘gives [her] pleasure’. Ultimately, Le foto proibite… could be said to be a picture about what J G Ballard called the ‘death of affect’ – overstimulation amongst the bourgeoisie and a resultant flattening of emotion – and Minou’s search for some form of stimulation which will provoke an emotional response.

Video

Le foto proibite… is presented on Arrow’s new Blu-ray release in an uncut form, with a running time of 95:45 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and fills just over 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. On choosing to play the film from the disc menu, the viewer is presented with the option to watch the film with Italian onscreen text (and accompanying English subtitles) or English onscreen text. Le foto proibite… is presented on Arrow’s new Blu-ray release in an uncut form, with a running time of 95:45 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and fills just over 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. On choosing to play the film from the disc menu, the viewer is presented with the option to watch the film with Italian onscreen text (and accompanying English subtitles) or English onscreen text.

Le foto proibite… was shot in Techniscope, and this presentation retains the film’s intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. As with other Techniscope pictures, the film was made using spherical lenses. Techniscope and similar 2-perf widescreen processes were cost-saving in the sense that they enabled the production of a widescreen image without the use of expensive anamorphic lenses, and by reducing the size of each frame by half (from 4-perforations to 2-perforations) halved the negative costs involved in making a film. (However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by more expensive lab costs, which for Techniscope productions steadily increased throughout the 1970s; this is sometimes cited as one of the reasons why Techniscope became less popular during the late 1970s and early 1980s.)  Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.) Lensed by prolific and consistent cinematographer Alexandro Ulloa, Le foto proibite…’s photography makes excellent use of the widescreen frame, employing depth within the photography in service of the narrative. Incidentally, the film features a clever, ironic edit: contemplating suicide, Minou climbs to the top of a crane and looks down. The camera descends rapidly, as if she has leapt from this height and we are being presented with her point-of-view; cut to a sugar cube being dropped into a cup of tea. A similar ironic cut is used in Douglas Hickox’s Theatre of Blood (1973), in which a shot of a body falling into the Thames is cut against the image of an ice cube being dropped into a glass of spirits. Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.) Lensed by prolific and consistent cinematographer Alexandro Ulloa, Le foto proibite…’s photography makes excellent use of the widescreen frame, employing depth within the photography in service of the narrative. Incidentally, the film features a clever, ironic edit: contemplating suicide, Minou climbs to the top of a crane and looks down. The camera descends rapidly, as if she has leapt from this height and we are being presented with her point-of-view; cut to a sugar cube being dropped into a cup of tea. A similar ironic cut is used in Douglas Hickox’s Theatre of Blood (1973), in which a shot of a body falling into the Thames is cut against the image of an ice cube being dropped into a glass of spirits.

This presentation of Le foto proibite… is a new 2k restoration based on the film’s negative. By going back to the negative, Arrow’s presentation has a greater resemblance to Techniscope films of the 1960s and early 1970s, printed using the due transfer process, rather than the standard Kodak colour printing process used for Techniscope pictures made during the mid/late 1970s. Contrast levels are very good, with richly defined midtones being present and some good, subtle curves into the toe and shoulder. Blacks are deep and inky. In all, contrast levels seem commensurate with Techniscope pictures during the era of the dye transfer process. There are some scenes shot using bold chiaroscuro lighting which provides a sense of depth to the photography, and these are communicated very well – details appearing framed by shadow or a portion of an actor’s face lit strongly, the light falling off into deepest black around them. Damage is limited to a few minor marks in the emulsions, here and there. The level of detail within the presentation is very pleasing, fine detail being articulated within close-ups. Skin-tones are naturalistic and colours are rich and consistent throughout the presentation. A few scenes feature strong use of primary coloured lights, and these are articulated superbly within this presentation. Finally, the encode to disc retains the structure of a 35mm Techniscope production.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

The disc menus provide the viewer with the option of watching the film in Italian, via a LPCM 1.0 track with optional English subtitles, or in English, via a similar LPCM 1.0 track with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. Though the thrust of the narrative is the same throughout, the two tracks differ in some interesting ways, with the English track changing the names of some of the characters. Both audio tracks are similar in terms of their range and depth, which is good. The subtitles are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by film critic Kat Ellinger. Ellinger suggests a link between the title of Le foto proibite… and Petri’s Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto/Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (also 1970). Ellinger talks about the photography of the film, though she perhaps credits Ercoli too much with the film’s photographic aesthetic – when, in terms of its ‘look’ (including its confident use of the widescreen frame and the expressionistic lighting), the film arguably bears the signature of Ulloa, the highly experienced cinematographer chosen to shoot the picture. (Near the start of the track, Ellinger makes a slight error in referring to Techniscope as a ‘stock’ when in fact it was a photographic process.) Ellinger spends much time outlining the paradigms of the giallo all’italiana, which as noted above is a notoriously difficult thing to pin down – much as it’s impossible to provide an all-inclusive definition of film noir. She makes an impassioned claim for the female-oriented suspense melodrama filone within the Italian-style thriller as being sidelined in favour of the more graphic examples of the form. This for a long time was a truism but since the digital age, during which Sergio Martino’s work in particular has come to be celebrated/idolised by fans of the form, it seems to be changing.

- ‘Private Pictures’ (44:15). This documentary features some archival interviews with Nieves Navarro and Luciano Ercoli (interviewed separately), alongside footage of a new interview with Ernesto Gastaldi. Ercoli reflects on how he became a film director, working his way up through the proverbial ranks. Navarro talks about her role in the picture and her character’s relationship with Minou, Dagmar Lassander’s character, suggesting that her interpretation of the picture is that Minou ‘was bored with her husband […..] Because it’s always the husband’s fault, even in movies’. Gastaldi considers Le foto proibite…’s place in the pictures he wrote for Ercoli, and he talks at length about how the finished picture differed from his original script, suggesting some dissatisfaction with Ercoli’s downplaying of the psychological aspects of Gastaldi’s script in favour of a greater emphasis on erotic spectacle and violence. - ‘The Forbidden Soundtrack of the Big Three’ (47:05). Lovely Jon, a connoisseur of soundtrack albums, discusses Morricone’s score for Le foto proibite… - ‘The Forbidden Lady’ (44:03). Footage of a 2016 interview with Dagmar Lassander, conducted at the Festival of Fantastic Films in Manchester, sees Lassander reflecting on her life and acting career. Audio quality isn’t geat but the interview is interesting and Lassander’s recollections are lucid and detailed. - Italian Theatrical Trailer (3:13). - English Theatrical Trailer (3:13). - Image Gallery (1:30).

Overall

Sitting somewhere at the periphery of the dominant paradigms surrounding the thrilling all’italiana, Le foto proibite… benefits from Ercoli’s confident handling of the material. Often compared with Henri-Georges Clouzeau’s Les Diaboliques (1955), Le foto proibite… is essentially a retelling of Bluebeard, like a number of films noir before it (such as the aforementioned The Secret Beyond the Door). Nevertheless, Ernesto Gastaldi’s script – written during a period in which Gastaldi was predominantly writing westerns all’italiana and before Gastaldi became closely associated with the thrilling/giallo) – is tightly-structured, even though in the interview contained on this disc Gastaldi expresses some credible dissatisfaction with Ercoli’s handling of the material. Ultimately, Le foto proibite… is a fairly insubstantial Italian-style thriller, though it’s engaging and particularly well-photographed and lit – and with a deeply memorable score from Ennio Morricone. Sitting somewhere at the periphery of the dominant paradigms surrounding the thrilling all’italiana, Le foto proibite… benefits from Ercoli’s confident handling of the material. Often compared with Henri-Georges Clouzeau’s Les Diaboliques (1955), Le foto proibite… is essentially a retelling of Bluebeard, like a number of films noir before it (such as the aforementioned The Secret Beyond the Door). Nevertheless, Ernesto Gastaldi’s script – written during a period in which Gastaldi was predominantly writing westerns all’italiana and before Gastaldi became closely associated with the thrilling/giallo) – is tightly-structured, even though in the interview contained on this disc Gastaldi expresses some credible dissatisfaction with Ercoli’s handling of the material. Ultimately, Le foto proibite… is a fairly insubstantial Italian-style thriller, though it’s engaging and particularly well-photographed and lit – and with a deeply memorable score from Ennio Morricone.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Le foto proibite… contains an excellent presentation of the main feature that is accompanied by some good contextual material. The interviews with Ercoli, Navarro and Gastaldi are superb, and the comments from Lassander – delivered onstage at the Festival of Fantastic Films in 2016 – are illuminating. This is a pleasing release of a fairly lightweight example of the thrilling all’italiana. References: Bondanella, Peter, 2009: A History of Italian Cinema. London: Continuum International Publishing Dyer, Richard, 2015: Lethal Repetition: Serial Killing in European Cinema. London: Palgrave Macmillan Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Maryland: Scarecrow Press La-Janisse, Kier, 2012: House of Pyschotic Women: An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis in Horror and Exploitation Films. London: FAB Press Met, Philippe, 2006: ‘“Knowing Too Much” About Hitchcock: The Genesis of the Italian Giallo’. In: Boyd, David & Palmer, R Barton (eds), 2006: After Hitchcock: Influence, Imitation, and Intertextuality. University of Texas Press: 195-214 Olney, Ian, 2013: Euro Horror: Classic European Cinema in Contemporary American Culture. Indiana University Press Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|