|

|

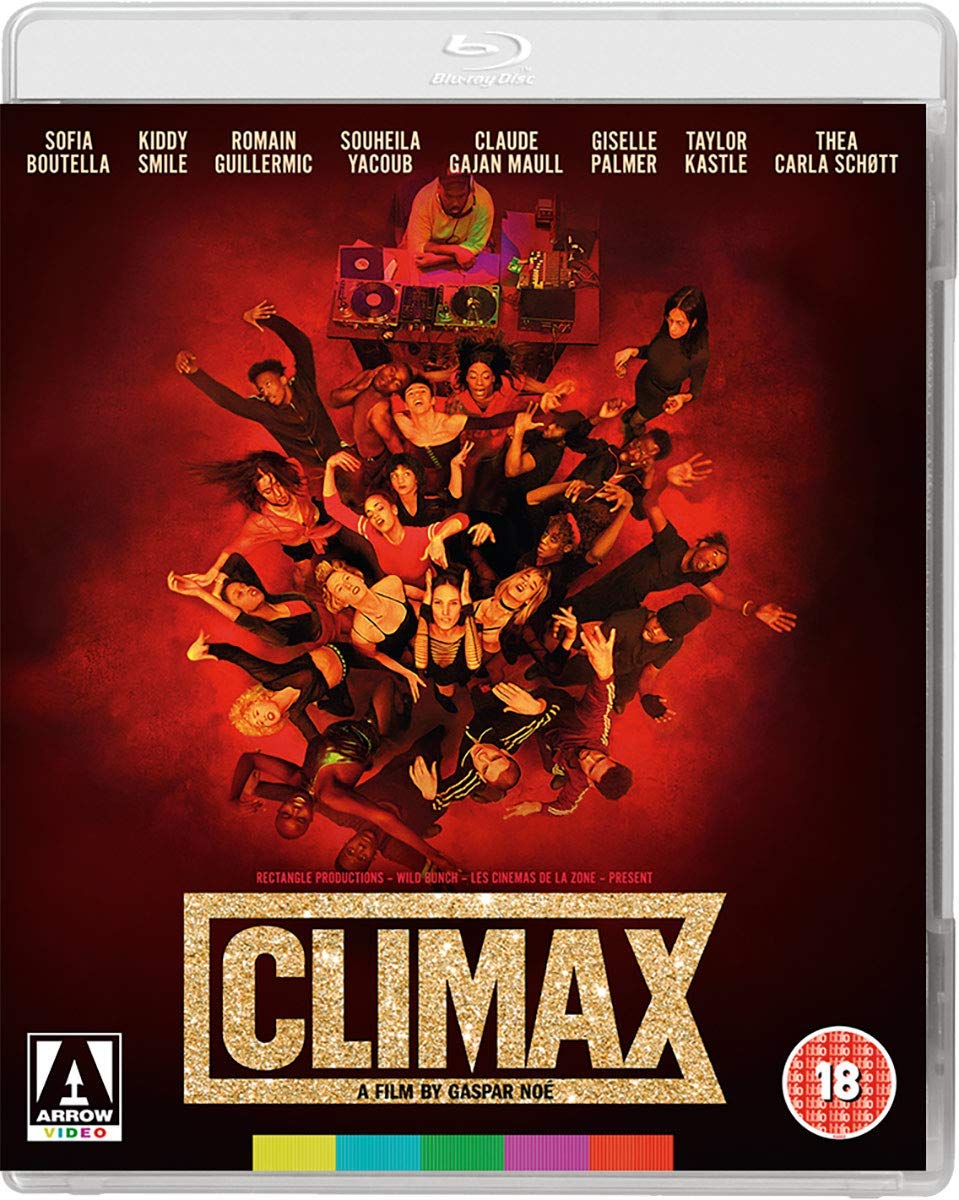

Climax (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th February 2019). |

|

The Film

Climax (Gaspar Noe, 2018) Climax (Gaspar Noe, 2018)

Synopsis: A troupe of dancers, from diverse backgrounds, gather in an empty school to rehearse for a show, under the leadership of their manager Emmanuelle (Claude-Emmanuelle Gajan-Maull). Emmanuelle, who is in attendance with her young son Tito (Vince Galliot Cumant), has provided sangria for an after-rehearsal party. Various factions emerge, and tensions too, including between David (Romain Guillermic) and Selva (Sofia Boutella), who have an on-again, off-again relationship. During the party, one of the dancers, Lou (Souheila Yacoub), reveals to Selva that she is pregnant. As the party progresses, the dancers become increasingly intoxicated; their behaviour becomes strange and inhibitions are stripped away. Selva begins to realise that the sangria is spiked. At first she suspects Emmanuelle but soon realises that Emmanuelle is innocent. As others in the group agree that the sangria has been laced with a hallucinogen, they round on Omar (Adrien Sissoko), who as a teetotaller hasn’t touch the drink. After an argument, Omar exits the school. Meanwhile, Emmanuelle finds Tito drinking the sangria. Scared for his safety, she locks him in the schools electrical cupboard, warning him not to touch the circuit breakers. Experiencing a hallucination involving cockroaches swarming into the cupboard, Tito screams for his mother. Selva retreats to an isolated room with Lou, but Dom bursts in and accuses Lou of spiking the drink. (Dom suspects Lou because like Omar, Lou hasn’t touched the alcohol.) Lou tells Dom that she is pregnant, but Dom accuses Lou of being a ‘lying bitch’ and knees her in the stomach. Lou collapses to the floor, and Dom beats her cruelly and viciously. In another room, two women argue over cocaine, with the result that one of the women’s hair catches fire.  Lou makes it back to the main hall, where Dom encourages the others to round on Lou and torment her. This causes Lou to begin to cut herself. Meanwhile, Tito screams in terror from within the electrical cupboard, and Emmanuelle discovers she has lost the key and cannot release her son. As David is being beaten by a group of men, the lights cut out and Tito’s cries fall into silence; Emmanuelle realises that her young son has touched the circuit breakers and, as a consequence, been killed. The events in the hall become increasingly like a representation of hell. Lou makes it back to the main hall, where Dom encourages the others to round on Lou and torment her. This causes Lou to begin to cut herself. Meanwhile, Tito screams in terror from within the electrical cupboard, and Emmanuelle discovers she has lost the key and cannot release her son. As David is being beaten by a group of men, the lights cut out and Tito’s cries fall into silence; Emmanuelle realises that her young son has touched the circuit breakers and, as a consequence, been killed. The events in the hall become increasingly like a representation of hell.

Critique: ‘A French film and proud of it’, declares an onscreen title over the image of a French flag, the camera pulling out to reveal the ‘flag’ is a tricoloured piece of fabric hanging behind the booth where Daddy, the DJ, works his magic, playing a remix of Cerrone’s disco classic ‘Supernature’ on his turntables. What follows is a bravura sequence in which the principal characters perform various types of dance – Krumping, Vogueing, Punking and Waacking with glee – all performed in a long take that lasts almost fifteen minutes. Driven by the beat of the music and the exuberance of the performers, Noe lulls the film’s viewer into a false sense of security, encouraging them to share in the joy of these young people, expressing themselves through a genre of dance and music known for its inclusive qualities. Regardless of sex, ethnicity or sexuality, the dancers are united through their energetic routines.  However, as the dance routine ends and the various groups retreat into their factions to socialise, we begin to see the cracks beneath this façade: even within this outwardly inclusive community, we see the various groups treating others with casual scorn. ‘I’ve seen too much of it’, one of the men says in relation to the French flag that is sitting behind Daddy’s DJ booth, counteracting the title that concludes the film’s opening credits (‘A French film and proud of it’). David and Omar talk about the décor within the school, Omar stating that ‘The crosses are creepy, man’. Another young man asks, ‘Since when have God and dance gone together?’ Rocco and another member of the troupe talk about their sexual conquests, discussing women as if they are pieces of meat in a butcher’s shop. Meanwhile, referring to Psyche and Ivana, David asserts, ‘Dyke stuff never works [….] They need cock’. For their part, the women refer to David as ‘a ticket to an STD’. This latent violence and hostility manifests itself more directly as the narrative progresses; in other words, the spiked sangria is only a catalyst for the manifestation of divisions and seething resentment that already exists within the group gathered in the school. However, as the dance routine ends and the various groups retreat into their factions to socialise, we begin to see the cracks beneath this façade: even within this outwardly inclusive community, we see the various groups treating others with casual scorn. ‘I’ve seen too much of it’, one of the men says in relation to the French flag that is sitting behind Daddy’s DJ booth, counteracting the title that concludes the film’s opening credits (‘A French film and proud of it’). David and Omar talk about the décor within the school, Omar stating that ‘The crosses are creepy, man’. Another young man asks, ‘Since when have God and dance gone together?’ Rocco and another member of the troupe talk about their sexual conquests, discussing women as if they are pieces of meat in a butcher’s shop. Meanwhile, referring to Psyche and Ivana, David asserts, ‘Dyke stuff never works [….] They need cock’. For their part, the women refer to David as ‘a ticket to an STD’. This latent violence and hostility manifests itself more directly as the narrative progresses; in other words, the spiked sangria is only a catalyst for the manifestation of divisions and seething resentment that already exists within the group gathered in the school.

Gaspar Noe takes as the setting for Climax a cultural context (dance culture) known for its inclusivity, populating the film with characters from various minority groups – based on ethnicity, gender and sexuality – and, as the narrative progresses, he reveals the hostility and subtly fascistic mentality within and amongst these individuals. When the dancers realise that the sangria has been spiked with a hallucinogen (presumed to be LSD), they embark on a witch-hunt, rounding on various ‘victims’ (Emmanuelle, Omar, Lou) and accusing them of putting the drug in the drink. It’s an intentionally provocative stance to take, counter to hegemonic strategies. The setting (behind the scenes of preparation for a stage production) recalls the whodunit structure of Michele Soavi’s Italian thriller/horror picture Stagefright (1987), and the manner in which Noe reveals the violence that exists between the ‘civilised’ surface of his characters brings to mind Robert Ardrey’s 1966 book The Territorial Imperative, in which Ardrey suggests that an evolutionary-driven instinct for territory and ownership drives most, if not all, human behaviour. Ardrey’s deterministic suggestion that an instinctual aggression exists beneath the surface of all human endeavours was a strong influence on the films of Stanley Kubrick (particularly, 1971’s A Clockwork Orange and 1989’s Full Metal Jacket) and Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972), in particular, essayed the idea of the beast that exists within an outwardly civilised person in its depiction of David’s (Dustin Hoffman) transition from meek mathematician to a man willing to use horrendous violence to defend the house and wife that constitute his ‘territory’. Climax’s emphasis on tribalism and the latent violence that is unleashed by the spiked sangria suggests Noe is expounding a similar perspective on human nature to that expressed in Straw Dogs, in particular. Gaspar Noe takes as the setting for Climax a cultural context (dance culture) known for its inclusivity, populating the film with characters from various minority groups – based on ethnicity, gender and sexuality – and, as the narrative progresses, he reveals the hostility and subtly fascistic mentality within and amongst these individuals. When the dancers realise that the sangria has been spiked with a hallucinogen (presumed to be LSD), they embark on a witch-hunt, rounding on various ‘victims’ (Emmanuelle, Omar, Lou) and accusing them of putting the drug in the drink. It’s an intentionally provocative stance to take, counter to hegemonic strategies. The setting (behind the scenes of preparation for a stage production) recalls the whodunit structure of Michele Soavi’s Italian thriller/horror picture Stagefright (1987), and the manner in which Noe reveals the violence that exists between the ‘civilised’ surface of his characters brings to mind Robert Ardrey’s 1966 book The Territorial Imperative, in which Ardrey suggests that an evolutionary-driven instinct for territory and ownership drives most, if not all, human behaviour. Ardrey’s deterministic suggestion that an instinctual aggression exists beneath the surface of all human endeavours was a strong influence on the films of Stanley Kubrick (particularly, 1971’s A Clockwork Orange and 1989’s Full Metal Jacket) and Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972), in particular, essayed the idea of the beast that exists within an outwardly civilised person in its depiction of David’s (Dustin Hoffman) transition from meek mathematician to a man willing to use horrendous violence to defend the house and wife that constitute his ‘territory’. Climax’s emphasis on tribalism and the latent violence that is unleashed by the spiked sangria suggests Noe is expounding a similar perspective on human nature to that expressed in Straw Dogs, in particular.

Like Noe’s other films, Climax provokes an immediate visceral response that is followed by a latent cognitive response. Speaking personally, as with my first experiences of watching Seul contre tous (1998) and Irreversible (2002) on their cinema release (and Enter the Void, 2009, and Love, 2015, on their home video releases), I found much of Climax repulsive whilst watching the film; but the picture lingers in the memory, encouraging reflection on its themes and ideas, and a day or two after watching Climax I couldn’t help thinking of it as an astute meditation on tribalism and latent violence in modern society – and how this is masked through diversion/escapist entertainment (in this case, dance). In other words, the film offers a critique of the bread and circuses (reworked here as sangria and dance) model for social stability, exploring how this masks an appetite for cruelty. The video interviews/auditions that begin the film, depicted on an on-screen CRT television set that is positioned between stacks of videotapes and books that reflect Noe’s own taste in cinema and literature (Suspiria, Querelle, Luis Bunuels’ book Mon dernier soupir, Claude Guillon and Yves Le Bonniec’s hugely controversial tome Suicide, mode d’emploi), show the young people who populate the narrative waxing lyrical about the unifying nature of dance. ‘Dance is everything. It’s all I have’, one of them comments. Dance is here framed by the interviewees as liberatory. However, violence – linguistic, at first – is present at the beginning, in the quietly (and sometimes, not so quietly) repulsive nature of drunken conversations; but it evolves and reveals itself more directly with a catalyst (the spiked sangria). Ultimately, Psyche’s psychological experiment reveals a truth as profound as Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Etudy or Milgram’s studies in obedience. And like Noe’s other films, I’m sure my feelings about and interpretation of Climax will evolve as time passes. Like Noe’s other films, Climax provokes an immediate visceral response that is followed by a latent cognitive response. Speaking personally, as with my first experiences of watching Seul contre tous (1998) and Irreversible (2002) on their cinema release (and Enter the Void, 2009, and Love, 2015, on their home video releases), I found much of Climax repulsive whilst watching the film; but the picture lingers in the memory, encouraging reflection on its themes and ideas, and a day or two after watching Climax I couldn’t help thinking of it as an astute meditation on tribalism and latent violence in modern society – and how this is masked through diversion/escapist entertainment (in this case, dance). In other words, the film offers a critique of the bread and circuses (reworked here as sangria and dance) model for social stability, exploring how this masks an appetite for cruelty. The video interviews/auditions that begin the film, depicted on an on-screen CRT television set that is positioned between stacks of videotapes and books that reflect Noe’s own taste in cinema and literature (Suspiria, Querelle, Luis Bunuels’ book Mon dernier soupir, Claude Guillon and Yves Le Bonniec’s hugely controversial tome Suicide, mode d’emploi), show the young people who populate the narrative waxing lyrical about the unifying nature of dance. ‘Dance is everything. It’s all I have’, one of them comments. Dance is here framed by the interviewees as liberatory. However, violence – linguistic, at first – is present at the beginning, in the quietly (and sometimes, not so quietly) repulsive nature of drunken conversations; but it evolves and reveals itself more directly with a catalyst (the spiked sangria). Ultimately, Psyche’s psychological experiment reveals a truth as profound as Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Etudy or Milgram’s studies in obedience. And like Noe’s other films, I’m sure my feelings about and interpretation of Climax will evolve as time passes.

The opening titles of the film suggest it is based on ‘true events’ that ‘happened in the winter of 1996’. There’s no evidence that it is, and certainly Noe seems to be using this assertion in a similar manner to which it was used by writers of early Gothic novels (such as Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, 1764) – to allow him to depict the undepictable by eroding the thin boundary between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’. Driven by the primal beat of the music, the behaviour of the various dancers becomes increasingly hostile, moments of physical violence exploding like bombs – such as Dom’s brutal beating of Lou, who is pregnant, which recalls the Butcher’s beating of his pregnant wife in Seul contre tous. The violence that is enacted within Climax towards the new generation is horrifying, though it is far from graphic. As a parent, the death of Tito – represented simply by Tito’s cries for his mother, followed by the lights shorting and a silence that symbolises Tito’s death – is very difficult to watch. In cinema, children are often used to represent the potential for future growth, so harm to them is always symbolic, and by allowing the pregnant Lou to be beaten (and then descend into self-mutilation) and ensuring Tito dies after being locked in the electricity cupboard, Noe offers a deeply nihilistic depiction of society. As Lou observes early in the film, ‘This is not a good place for a kid’. This isn’t the only piece of foreshadowing that takes place in the film’s early sequences. During his conversation with another male dancer, Rocco notes that ‘This place has some weird shit. I can feel it. Sacrifices… some strange shit’. ‘You mean like a sect?’, the other man asks. ‘I don’t dig the vibe in this group’, Rocco says, ‘They’re weird. And this school, it magnifies the sense of weirdness’. The opening titles of the film suggest it is based on ‘true events’ that ‘happened in the winter of 1996’. There’s no evidence that it is, and certainly Noe seems to be using this assertion in a similar manner to which it was used by writers of early Gothic novels (such as Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, 1764) – to allow him to depict the undepictable by eroding the thin boundary between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’. Driven by the primal beat of the music, the behaviour of the various dancers becomes increasingly hostile, moments of physical violence exploding like bombs – such as Dom’s brutal beating of Lou, who is pregnant, which recalls the Butcher’s beating of his pregnant wife in Seul contre tous. The violence that is enacted within Climax towards the new generation is horrifying, though it is far from graphic. As a parent, the death of Tito – represented simply by Tito’s cries for his mother, followed by the lights shorting and a silence that symbolises Tito’s death – is very difficult to watch. In cinema, children are often used to represent the potential for future growth, so harm to them is always symbolic, and by allowing the pregnant Lou to be beaten (and then descend into self-mutilation) and ensuring Tito dies after being locked in the electricity cupboard, Noe offers a deeply nihilistic depiction of society. As Lou observes early in the film, ‘This is not a good place for a kid’. This isn’t the only piece of foreshadowing that takes place in the film’s early sequences. During his conversation with another male dancer, Rocco notes that ‘This place has some weird shit. I can feel it. Sacrifices… some strange shit’. ‘You mean like a sect?’, the other man asks. ‘I don’t dig the vibe in this group’, Rocco says, ‘They’re weird. And this school, it magnifies the sense of weirdness’.

Video

Presented in 1080p (and using the AVC codec), Climax fills a little over 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is uncut and runs for 96:30 mins. Presented in 1080p (and using the AVC codec), Climax fills a little over 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film is uncut and runs for 96:30 mins.

The film was shot digitally, on the ARRI ALEXA Mini. The photography in Climax, by Benoit Debie (who has worked on all of Noe’s features since Irreversible), is as ‘authored’ as the photography in Noe’s other films. The screen is often saturated with red: the red dancefloor, which becomes a symbol of danger, is complemented as the hallucinations take hold by vivid red gels on the lights (and occasionally other primary colours too). In one sequence, Noe holds an overhead shot of the dancefloor as a succession of the dancers strut their stuff in the centre of a circle, Noe connecting this circular composition to overhead shots of the vinyl records turning on Daddy’s turntable, the overhead camera beginning to rotate in mimicry of the vinyl records. Given the fact that it was shot digitally, Climax features some strong midtones and good, subtle gradation into the toe during the film’s many low-light scenes. In the film’s opening sequence, the brilliant white of the snow outside the school is deliberately blown out. Colours are incredible rich and deep throughout the picture. Finally, the encode to disc presents no glaring problems. This is a strong presentation of the digital source material.

Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track; dialogue is predominantly in French with some English lines of dialogue here and there. The French dialogue is accompanied by optional English subtitles. (English lines of dialogue aren’t subtitled.) The soundscape is incredibly immersive, the primal beat of the music driven through some excellent sound separation, the track exhibiting depth and range. The subtitles are easy to read and seem to be accurate to the French dialogue, though much of the French spoken in the film is slang – which is notoriously difficult to translate. (The subtitles managed to carry the gist of this slang, however.)

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Gaspar Noe. Noe provides a commentary track in English. He talks about the logistics of shooting the picture and explains some of the ambiguities of the story. He reflects on some of the techniques he employed within the film, and the track offers a fascinating and illuminating insight into Noe’s approach to the filmmaking process. - ‘An Antidote to the Void’ (14:06). Speaking in English, Gaspar Noe speaks about Climax and discusses the origins of Climax and his intentions in making the picture. Noe suggests the structure of the film, with Lou’s collapse in the snow outside the school, was influenced by disaster movies. He reflects on the film’s examination of tribalism and drinking/drug culture, and he talks about his methods in making the picture. - ‘Performing Climax’ (28:14). Some of the actors from the film – Kiddy Smile (Daddy), Romain Guillermic (David) and Souheila Yacoub (Lou) – discuss their work on the film, talking about Noe’s approach to directing his actors and reflecting on how they came to be involved in the picture. They talk about the challenges they faced in essaying their roles. The participants speak in French; their comments are supported by optional English subtitles. - ‘Disco Infernal: The Sounds of Climax’ (24:04). Film critic Alan Jones, an enthusiast of disco culture who has written an excellent book on disco (Saturday Night Fever: The Story of Disco), talks about the film’s depiction of dance culture, commenting on Noe’s use of music within the picture and offering a track-by-track analysis of the manner in which specific tracks are used.

- ‘Shaman of the Screen: The Films of Gaspar Noe’ (29:23). Alexandra Heller-Nicholas narrates a video essay about Noe’s cinema that traces his approach back to his work on French television in the 1990s. Heller-Nicholas compares Noe to the figure of the shaman, suggesting that his work has a hypnagogic quality. This is an excellent little piece that is illustrated with some rich footage from Noe’s various works. (Be warned: the clip uses some of the more explicit footage from Noe’s films, such as the close-up of Karl Glusman’s ejaculating penis from Love.) - ‘Shoot’ (3:14). This short film as made by Noe as part of a 2014 project by Daniel Gruener. Beginning with an image of the French flag, ‘Shoot’ sees a group of young people kicking a football around a building site, the camera adopting the football’s point-of-view. It’s a dizzying and inventive short film, with inventive use of photography and audio to suggest a sense of concussion. - Music Videos: SebastiAn, ‘Love in Motion’ (3:59); Thomas Bangalter, ‘Sangria’ (3:18). The first of these is a music video directed by Noe in 2012, and the second is comprises footage shot for Climax. - Trailer (1:00).

Overall

Noe’s international breakout picture was Seul contre tous, which I vividly remember seeing in Dublin in 1999, around the time of that year’s Dublin Film Festival. (Bizarrely, I remember seeing posters for the film dotted about the city, almost as if it were a Hollywood blockbuster.) Seul contre tous was an impactful picture which marked Noe as a filmmaker unafraid of alienating his audience and perhaps even wilfully goading filmgoers into a negative reaction towards the picture. Noe’s subsequent features have all followed in the same vein, and in interviews Noe has proudfully boasted of the numbers of people who, with each subsequent picture, walk out of screenings of his films. On the other hand, Climax has been received quite differently, Noe being startled with the amount of praise the film has attracted. Certainly, though the imagery is less combative than that in some of Noe’s other feature films, the ideas and themes within Climax are no less confrontational than those in, say, Irreversible. In Climax, Noe’s handling of the deaths of the two representatives of the new generation is not graphic but is nevertheless utterly disturbing, and the manner in which both Tito dies and the pregnant Lou is beaten to the point of miscarriage are integral to the nihilistic worldview put forwards by Climax: these two deaths represent the extinguishing of any possibility of growth, the death of the future itself. Noe’s depiction of dance culture seems to suggest a layer of brutality beneath the surface of escapist entertainment – an examination of the ‘bread and circuses’ concept espoused by Juvenal – and his deterministic emphasis on tribalism and ‘essential’ violence seems to deliberately invite comparisons with Robert Ardrey and filmmakers whose work was inspired by Ardrey’s The Territorial Imperative (for example, Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs). The setting also brings to mind Horace McCoy’s dark depiction of a dance marathon in the 1935 novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Noe’s international breakout picture was Seul contre tous, which I vividly remember seeing in Dublin in 1999, around the time of that year’s Dublin Film Festival. (Bizarrely, I remember seeing posters for the film dotted about the city, almost as if it were a Hollywood blockbuster.) Seul contre tous was an impactful picture which marked Noe as a filmmaker unafraid of alienating his audience and perhaps even wilfully goading filmgoers into a negative reaction towards the picture. Noe’s subsequent features have all followed in the same vein, and in interviews Noe has proudfully boasted of the numbers of people who, with each subsequent picture, walk out of screenings of his films. On the other hand, Climax has been received quite differently, Noe being startled with the amount of praise the film has attracted. Certainly, though the imagery is less combative than that in some of Noe’s other feature films, the ideas and themes within Climax are no less confrontational than those in, say, Irreversible. In Climax, Noe’s handling of the deaths of the two representatives of the new generation is not graphic but is nevertheless utterly disturbing, and the manner in which both Tito dies and the pregnant Lou is beaten to the point of miscarriage are integral to the nihilistic worldview put forwards by Climax: these two deaths represent the extinguishing of any possibility of growth, the death of the future itself. Noe’s depiction of dance culture seems to suggest a layer of brutality beneath the surface of escapist entertainment – an examination of the ‘bread and circuses’ concept espoused by Juvenal – and his deterministic emphasis on tribalism and ‘essential’ violence seems to deliberately invite comparisons with Robert Ardrey and filmmakers whose work was inspired by Ardrey’s The Territorial Imperative (for example, Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs). The setting also brings to mind Horace McCoy’s dark depiction of a dance marathon in the 1935 novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

Filled with bravura photography (despite the picture being shot in a very condensed period of time) and some powerfully counterpunctive use of music, Noe’s Climax is a thought-provoking and openly combative picture. Fans of Noe’s work will know what to expect and won’t be disappointed. Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Climax is exceptional, featuring a tip-top presentation of the digitally-shot feature and some superb contextual material. In particular, Alan Jones’ analysis of the use of music in the film and Alexandra Heller-Nicholas’ video essay focusing on the evolution of Noe’s approach to cinema are both excellent and help to situate Climax firmly within context. Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|