|

|

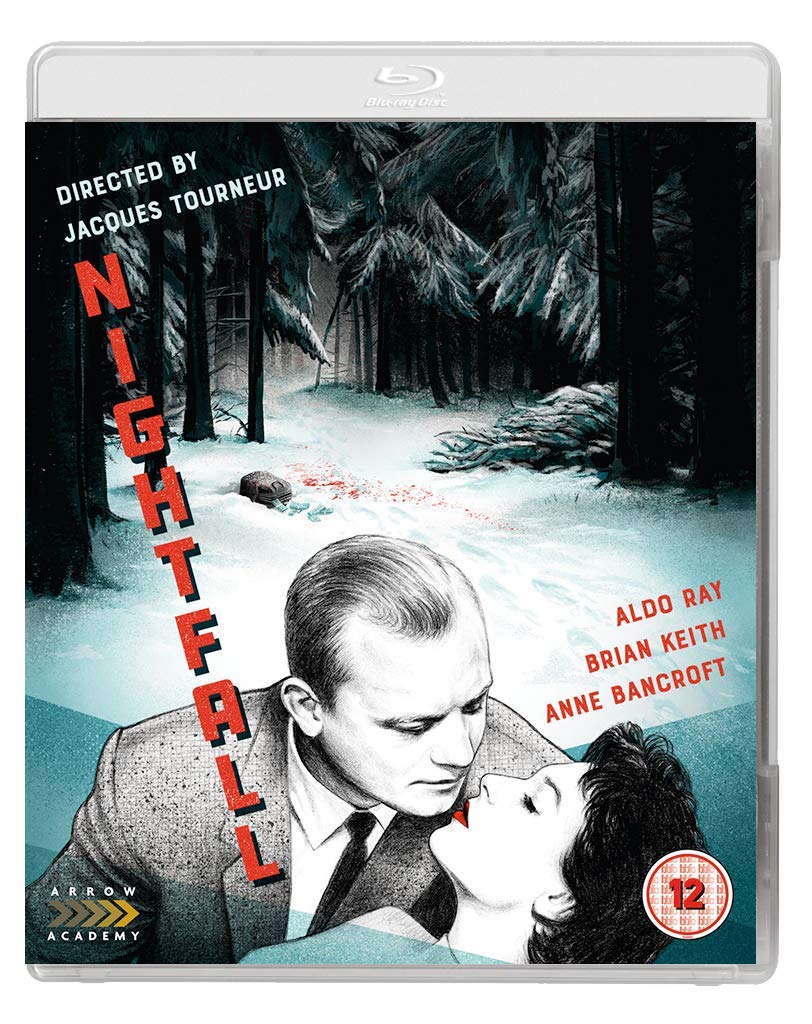

Nightfall (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th June 2019). |

|

The Film

Nightfall (Jacques Tourneur, 1956) Nightfall (Jacques Tourneur, 1956)

Synopsis: Commercial artist and veteran of the Battle of Okinawa Jim Rayburn (Aldo Ray) meets, in a restaurant, a model named Marie Gardner (Anne Bancroft). Marie asks Rayburn to loan her five dollars, and the two strike up a friendly conversation. ‘You sound like a man with a problem’, Marie observes. ‘Yeah, I got problems’, Rayburn tells her, ‘Who hasn’t?’ Meanwhile, insurance investigator Ben Fraser (James Gregory) has been keeping tabs on Rayburn, and he has been discussing the case with his wife Laura (Jocelyn Brando). Fraser has been charged with the task of investigating Rayburn, who is believed to have stolen $350,000 in a bank robbery in Wyoming. Fraser, who lives modestly, has grown sympathetic towards Rayburn, in whom he sees a similar level of frugal living – certainly not the kind of life one would expect from someone who has stolen a huge amount of money from a bank. As Rayburn leaves the restaurant, he is accosted by two hoodlums, John (Brian Keith) and the cruel Red (Rudy Bond). John and Red are the real bank robbers; they engineered the meeting between Marie, who believed John and Red to be detectives, and Rayburn, so that Marie would lead Rayburn into their hands. John and Red believe Rayburn knows where the money from the heist is, and they take him out to an oil field with the intention of crushing his limbs in a nodding donkey pump until he tells them where the cash is hidden.  Via flashbacks, we learn the story of the money: John and Red stole the $350,000 from a bank but crashed their car in the Wyoming countryside, close to where Rayburn and his friend Doc (Frank Albertson) were camping on a fishing trip. Doc and Rayburn came to the aid of the two men, unaware of their violent tendencies. However, not wanting any witnesses, Red convinced John that they should kill Doc and Rayburn, making the deaths look like a murder-suicide. Red shot and killed Doc but missed Rayburn, who played dead. Leaving the scene, Red confused the money bag with Doc’s medical satchel, which is similar in appearance, and accidentally left the money behind. When he came to, Rayburn discovered the bag containing the money. He took it and hid the cash near a ruined building in the middle of nowhere before – knowing that he will be the chief suspect in Doc’s murder – going on the lam, seeking refuge in the city where John and Red found him. Via flashbacks, we learn the story of the money: John and Red stole the $350,000 from a bank but crashed their car in the Wyoming countryside, close to where Rayburn and his friend Doc (Frank Albertson) were camping on a fishing trip. Doc and Rayburn came to the aid of the two men, unaware of their violent tendencies. However, not wanting any witnesses, Red convinced John that they should kill Doc and Rayburn, making the deaths look like a murder-suicide. Red shot and killed Doc but missed Rayburn, who played dead. Leaving the scene, Red confused the money bag with Doc’s medical satchel, which is similar in appearance, and accidentally left the money behind. When he came to, Rayburn discovered the bag containing the money. He took it and hid the cash near a ruined building in the middle of nowhere before – knowing that he will be the chief suspect in Doc’s murder – going on the lam, seeking refuge in the city where John and Red found him.

In the present, Rayburn manages to escape from John and Red and flees back to the city, where he seeks refuge in Marie’s apartment – having remembered Marie’s address from their previous meeting. Rayburn and Marie commit themselves to journeying by bus to Wyoming, with the intention of finding the money and turning it in to the police. Along the way, they encounter Fraser who, sympathetic to Rayburn, offers to help. However, they are still pursued by John and Red.  Critique: Adapted from the 1947 novel by David Goodis, Nightfall was directed by Jacques Tourneur. Tourneur’s career as a director spanned several genres, from horror pictures such as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), through Westerns like Canyon Passage (1946) and on to films noir such as Nightfall and Build My Gallows High / Out of the Past (1947). Tourneur shot Nightfall within a year of Night of the Demon (1957), his adaptation of M R James’ short story ‘Casting the Runes’ (1911). Though both Nightfall and Night of the Demon are superficially very different – one a film noir filmed in America and the other a horror picture shot in the UK – both share some extraordinarily crisp monochrome photography and tersely meaningful dialogue. Made close to the end of the classic film noir cycle, which is usually cited as beginning with John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) and ending with Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958), Nightfall makes rich use of real locations and, like many other latter day films noir it is in many respects a much more frank and combative picture in comparison with the often studio-bound films noir of the ‘40s. Critique: Adapted from the 1947 novel by David Goodis, Nightfall was directed by Jacques Tourneur. Tourneur’s career as a director spanned several genres, from horror pictures such as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), through Westerns like Canyon Passage (1946) and on to films noir such as Nightfall and Build My Gallows High / Out of the Past (1947). Tourneur shot Nightfall within a year of Night of the Demon (1957), his adaptation of M R James’ short story ‘Casting the Runes’ (1911). Though both Nightfall and Night of the Demon are superficially very different – one a film noir filmed in America and the other a horror picture shot in the UK – both share some extraordinarily crisp monochrome photography and tersely meaningful dialogue. Made close to the end of the classic film noir cycle, which is usually cited as beginning with John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) and ending with Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958), Nightfall makes rich use of real locations and, like many other latter day films noir it is in many respects a much more frank and combative picture in comparison with the often studio-bound films noir of the ‘40s.

The script for Nightfall, by Stirling Silliphant at the beginning of his long and illustrious career, is pin-sharp with a rich ear for hardboiled, symbolic dialogue. In the film’s opening sequence, through a series of oblique exchanges between a fellow passenger at the bus depot (who is later revealed to be Fraser, who becomes Rayburn’s greatest ally in his fight to clear his name) and a girl, played by Anne Bancroft, in a bar, we learn everything we need to know about the film’s protagonist, played by Aldo Ray – a laconic veteran of the war in the Pacific who is on the run from two sadistic bank robbers, John and the sadistic Red (played respectively by Brian Keith and a sneering Rudy Bond). Through subtle visual cues, we also learn that Rayburn is on the lam: the film’s opening shots are of a newspaper stand in the city, where Rayburn tries to hide his face from the light, indicative of his anxiety about being seen by the ‘wrong’ people. Additionally, the dialogue in the restaurant offers similarly subtle hints of Marie’s personality, informing us subtly that she has been battle-hardened in another warzone – that of relationships between the sexes. ‘The men I usually run into don’t want to talk to anyone but their wives, or secretaries’, she notes to Rayburn, ‘They seem to think conversation is a little old-fashioned’. ‘You sound bitter’, Rayburn responds good-humouredly. ‘Case hardened’, Marie corrects him. Nightfall is a picture of small, subtle gestures. In the flashbacks, before John and Red collide with and disrupt Doc and Rayburn’s world, Doc and Rayburn talk about Doc’s younger wife Eva, who is closer in age to Rayburn than her husband. Doc thanks Rayburn for his ‘strength of character’ in resisting any temptation to seduce Eva. Without saying anything, Rayburn pours out his cup of coffee and stands, turning away from Doc before trying to change the subject. Doc doesn’t register anything suspicious in Rayburn’s behaviour, but Rayburn’s gesture hints at subtle tensions in the relationship between Rayburn, (the unseen) Eva and Doc.  Nightfall is structured around three pairs: the insurance investigator Fraser and his wife; Rayburn and Marie; and the bank robbers John and Red. In discussing the film’s villains, John and Red, Chris Fujiwara – in Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall (1998) – suggests that John’s ‘quiet reasonableness’ acts as a bridge between the ‘casual sadism and quirky humour’ of Red and the good-natured Rayburn (235). Several times, John admits to a grudging admiration of Rayburn: upon their first meeting in the city, outside the restaurant, John tells Rayburn, ‘You cost us a lot of money trying to find you [….] I didn’t mind that. I liked the way you handled yourself. One, you didn’t go to the police [….] And two, you didn’t make trouble. You just disappeared. I liked that too [….] That’s because you’re tough. But after we get you where you aren’t so tough anymore, you’ll tell us. You’ll say anything we want you to say’. Certainly, described by a minor character as ‘look[ing] like a pair of unmatched bookends’, John and Red have much in common with Max and Al, the two assassins from Chicago who arrive in the small town of Summit to kill Ole Andreson, in Ernest Hemingway’s iconic 1927 short story ‘The Killers’: like Max and Al, John and Red have a back-and-forth patter that allies them with vaudeville comedians. ‘The Killers’ was, perhaps surprisingly given Hemingway’s status within the hardboiled tradition in American literature, the only of Hemingway’s stories to be adapted as a film noir (by Robert Siodmak in 1946; read our review of Arrow Academy’s Blu-ray release of that film here). Certainly, echoes of ‘The Killers’, and in particular the depiction of the two assassins as blackly comic vaudeville clowns – found their way into many subsequent films noir and examples of neo-noir too (for example, the depiction of Vince and Jules in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, 1994). In Nightfall, the ‘double act’ of John and Red, with their dry patter, jokes and witty retorts that are barbed with menace, seems a direct descendant of Max and Al’s relationship and their disruptive effect on George’s diner in the opening pages of ‘The Killers’. When Red threatens to put one of Rayburn’s arms in the nodding donkey pump at the oil field, John tells Rayburn that ‘He’s not fooling. When Red was a kid, they didn’t have any playgrounds. He’s sort of an adult delinquent’. Nightfall is structured around three pairs: the insurance investigator Fraser and his wife; Rayburn and Marie; and the bank robbers John and Red. In discussing the film’s villains, John and Red, Chris Fujiwara – in Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall (1998) – suggests that John’s ‘quiet reasonableness’ acts as a bridge between the ‘casual sadism and quirky humour’ of Red and the good-natured Rayburn (235). Several times, John admits to a grudging admiration of Rayburn: upon their first meeting in the city, outside the restaurant, John tells Rayburn, ‘You cost us a lot of money trying to find you [….] I didn’t mind that. I liked the way you handled yourself. One, you didn’t go to the police [….] And two, you didn’t make trouble. You just disappeared. I liked that too [….] That’s because you’re tough. But after we get you where you aren’t so tough anymore, you’ll tell us. You’ll say anything we want you to say’. Certainly, described by a minor character as ‘look[ing] like a pair of unmatched bookends’, John and Red have much in common with Max and Al, the two assassins from Chicago who arrive in the small town of Summit to kill Ole Andreson, in Ernest Hemingway’s iconic 1927 short story ‘The Killers’: like Max and Al, John and Red have a back-and-forth patter that allies them with vaudeville comedians. ‘The Killers’ was, perhaps surprisingly given Hemingway’s status within the hardboiled tradition in American literature, the only of Hemingway’s stories to be adapted as a film noir (by Robert Siodmak in 1946; read our review of Arrow Academy’s Blu-ray release of that film here). Certainly, echoes of ‘The Killers’, and in particular the depiction of the two assassins as blackly comic vaudeville clowns – found their way into many subsequent films noir and examples of neo-noir too (for example, the depiction of Vince and Jules in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, 1994). In Nightfall, the ‘double act’ of John and Red, with their dry patter, jokes and witty retorts that are barbed with menace, seems a direct descendant of Max and Al’s relationship and their disruptive effect on George’s diner in the opening pages of ‘The Killers’. When Red threatens to put one of Rayburn’s arms in the nodding donkey pump at the oil field, John tells Rayburn that ‘He’s not fooling. When Red was a kid, they didn’t have any playgrounds. He’s sort of an adult delinquent’.

Nightfall has a clever structure: the film runs two stories in tandem: Rayburn’s flight from John and Red; and John and Red’s terrorisation of Rayburn and Doc, the latter presented as flashbacks that are interspersed throughout the narrative. The film interweaves these flashbacks, showing how Ray’s character came to be in the crosshairs of John and Red, with Rayburn’s attempts to flee them in the present day. The flashbacks suggest a deep wound in Rayburn’s psyche, and it’s difficult not to see Nightfall as a picture that is ultimately an allegorical exploration of combat fatigue – or, in today’s parlance, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Additionally, in its juxtaposition of the diegetic present with the past, the film also establishes a conflict between the urban and the rural space. John and Red used the isolation of Rayburn and Doc’s campsite to torment and execute the two friends, framing them for the bank robbery; meanwhile, subsequently Rayburn sought to hide from the two hoodlums by fleeing to the metropolis, where he could blend into the crowd. Nightfall has a clever structure: the film runs two stories in tandem: Rayburn’s flight from John and Red; and John and Red’s terrorisation of Rayburn and Doc, the latter presented as flashbacks that are interspersed throughout the narrative. The film interweaves these flashbacks, showing how Ray’s character came to be in the crosshairs of John and Red, with Rayburn’s attempts to flee them in the present day. The flashbacks suggest a deep wound in Rayburn’s psyche, and it’s difficult not to see Nightfall as a picture that is ultimately an allegorical exploration of combat fatigue – or, in today’s parlance, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Additionally, in its juxtaposition of the diegetic present with the past, the film also establishes a conflict between the urban and the rural space. John and Red used the isolation of Rayburn and Doc’s campsite to torment and execute the two friends, framing them for the bank robbery; meanwhile, subsequently Rayburn sought to hide from the two hoodlums by fleeing to the metropolis, where he could blend into the crowd.

Chris Fujiwara suggests that thanks to its roots in David Goodis’ source novel, Nightfall more closely resembles Francois Truffaut’s Tirez sur la pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player, 1960) than Tourneur’s other major film noir, Out of the Past (Fujiwara, 1998: 237). Fujiwara suggests Nightfall shares with the Truffaut picture ‘the undercurrent of longing and unease, the vulnerable protagonist, and the solace and dread of urban anonymity’, along with the more obvious ‘journey into and a violent climax in a snowy country’ (ibid.). Nightfall also retains Goodis’ fundamental ‘tenderness and humanity […], its combination of despair, melancholy, and a humorous tenaciousness’ (ibid.). Certainly, the confluence of coincidences that take place in the narrative – from Doc and Rayburn’s first encounter with John and Red near their campsite, where John and Red’s car has overturned in an accident, to the manner in which John and Red catch up with Rayburn in the city – gives the film a strong vein of fatalism. This sense of one’s life being determined by forces outside one’s control is suggested in the film’s opening sequence, when Rayburn encounters Fraser at the bus depot. (Of course, at this point in the narrative Rayburn does not know who Fraser is.) Commenting casually on the heat, Fraser observes, ‘Wonder how they stand it [the heat] in the tropics’. ‘Born into it’, Rayburn responds pithily.

Video

Uncut and with a running time of 78:56 mins, Nightfall is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film fills slightly under 23Gb on the Blu-ray disc. Uncut and with a running time of 78:56 mins, Nightfall is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film fills slightly under 23Gb on the Blu-ray disc.

The film’s crisp 35mm monochrome photography is reproduced superbly on this Blu-ray release. The image is crisp and rich in fine detail, with superb contrast levels. Like Tourneur’s other pictures, the film features some superb low-key, naturalistic lighting: this was a characteristic of Tourneur’s films, the director preferring to shoot with either natural light or ‘logical’ light sources (ie, light which appears to be natural in its source). Consequently, a number of shots feature characters lit by a backlight with some subtle reflected light on their face. (There’s a superbly photographed night-time dialogue scene between Jocelyn Brando and James Gregory, which features Brando standing with a light source behind her, weak light reflected on her face so that her features are barely visible.) Other shots feature some bold chiaroscuro lighting, again based on the principal of mimicking natural light. Richly defined mid-tones are complemented by a pleasingly subtle drop into the toe. Details are retained in the shadows. Meanwhile, the curve into the shoulder is also quiet and subtle, with even highlights. There is little to no damage worth mentioning. The encode to disc is excellent and ensures the presentation retains the natural structure of 35mm film. The result is a very filmlike presentation. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is rich and deep with no distortion or other problems. The film opens with a romantic, swelling theme of the kind that was skewered a few years earlier in Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955). Nightfall’s main theme, ‘Nightfall’ sung by Al Hibbler, was released as a single with Hibbler’s ‘I’m Free’. The music is presented in the lossless track with superb fidelity. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and accurate in translating the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with journalist Bryan Reesman. Pop culture journalist Reesman offers a breathless commentary track in which he reflects on Nightfall’s position within the pantheon of film noir and talks about some of the locations used in this picture. He examines the parallels between this film and some of Jacques Tourneur’s other pictures, and he discusses the film’s depiction of American society in the 1950s. He talks about the careers of some of the actors in the picture. It’s a track that is densely packed with information. - ‘White and Black’ (15:41). Critic Philip Kemp offers an appreciation of Nightfall that situates the film within the career of Jacques Tourneur. He suggests Nightfall ‘almost undermine[s] and exploit[s]’ the conventions of film noir, arguing that the picture is a ‘post-modern’ film noir that selfconsciously deconstructs the paradigms of noir. Kemp reflects on Tourneur’s body of work, beginning with the horror pictures he made for Val Lewton, arguing that Tourneur often made the most of modest resources, preferring to use natural or ‘logical’ sources of light and avoiding obtuse ‘camera angles and distorting lenses’. Kemp compares the structure of Nightfall with that of Out of the Past and discusses the similarities between this film and Truffaut’s adaptation of Goodis’ Shoot the Piano Player. He suggests that Al Hibbler’s title song is ‘slushy’ and ‘cringeworthy’ and not in keeping with the material. Kemp also reflects on the casting of the picture, discussing in particular the qualities Aldo Ray brings to his role. - ‘Do I Look Like a Married Man?’ (17:07). Journalist Kat Ellinger narrates a video essay which reflects on some of the film’s themes, discussing how Tourneur stages his thematically darkest scenes in bright daylight, and considering how the film juxtaposes night and darkness in a similar manner to which it contrasts the urban and rural spaces. - Trailer (2:09). - Gallery (2:20).

Overall

With a brief running time of just under 80 minutes, Nightfall’s story moves along at a fair old clip. 1950s films noir, often more heavily shot on location, have a distinct flavour to the films noir of the 1940s, and it’s interesting to compare this film with Tourneur’s most famous film noir, Build My Gallows High. Nightfall has a superb script with a subtly symbolic use of dialogue, and the film’s photography – which, like Tourneur’s other pictures, emphasises natural (or natural-seeming) light and ‘straight’ angles, thus feeling very naturalistic – is arguably amongst the best of the films noir made towards the end of the classic period. The film is also anchored by some superb performances, from Ray and Bancroft to supporting players such as Keith and Rudy Bond – who excels in his role as the sadistic Red. With a brief running time of just under 80 minutes, Nightfall’s story moves along at a fair old clip. 1950s films noir, often more heavily shot on location, have a distinct flavour to the films noir of the 1940s, and it’s interesting to compare this film with Tourneur’s most famous film noir, Build My Gallows High. Nightfall has a superb script with a subtly symbolic use of dialogue, and the film’s photography – which, like Tourneur’s other pictures, emphasises natural (or natural-seeming) light and ‘straight’ angles, thus feeling very naturalistic – is arguably amongst the best of the films noir made towards the end of the classic period. The film is also anchored by some superb performances, from Ray and Bancroft to supporting players such as Keith and Rudy Bond – who excels in his role as the sadistic Red.

Arrow Academy’s new Blu-ray release of the film contains an absolutely superb presentation of the main feature and is supported by some very good contextual material, including an audio commentary by pop culture journalist Bryan Reesman and an interview with critic Philip Kemp. (The Kemp interview is the strongest of the special features included on this disc.) These features often overlap in their content and approach, however, but nevertheless their inclusion is to be commended. Noir fanatics will find this to be a most worthwhile purchase. References: Fujiwara, Chris, 1998: Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall. London: McFarland & Co. Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|