|

The Film

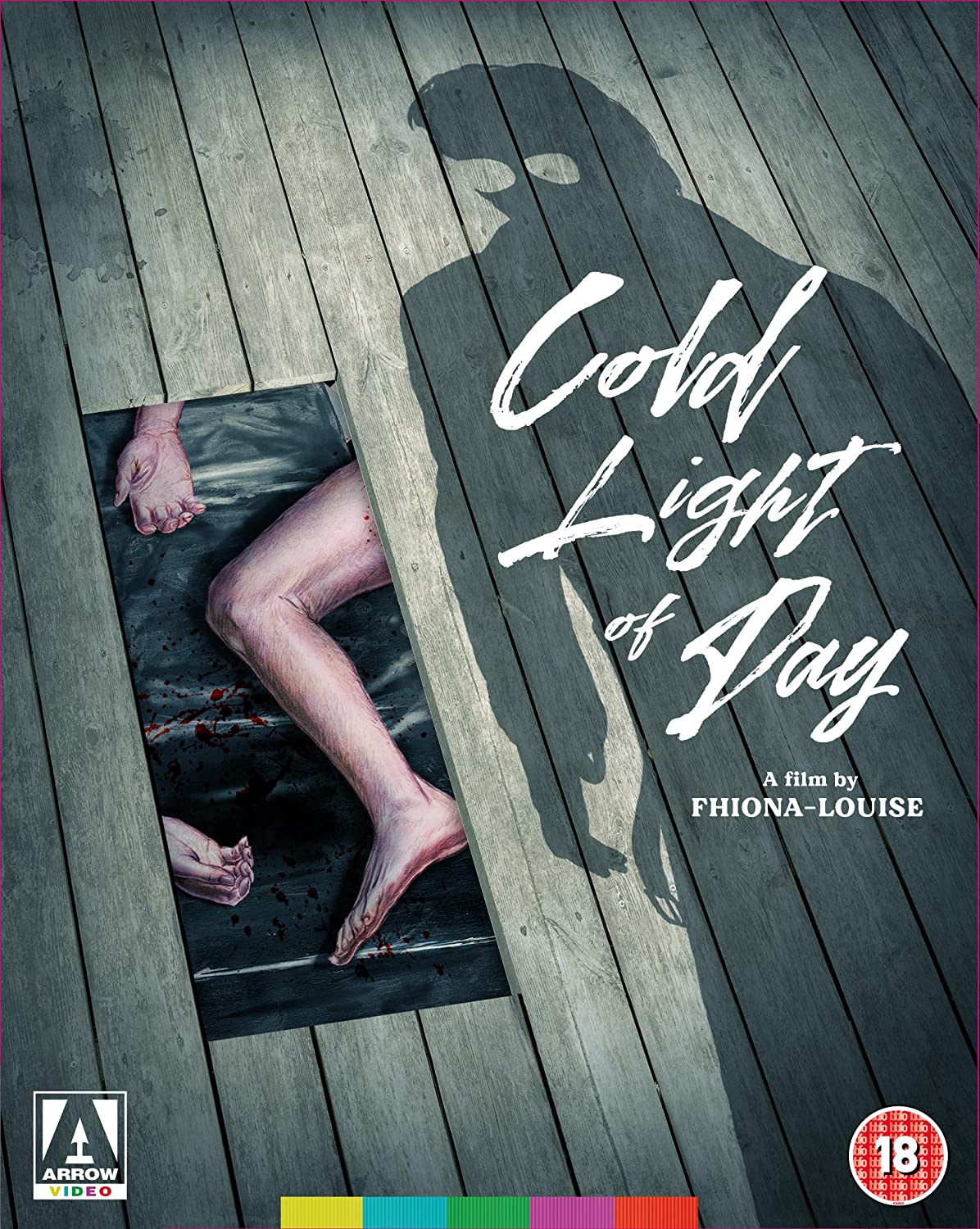

Cold Light of Day (Fhiona-Louise, 1989) Cold Light of Day (Fhiona-Louise, 1989)

I have a rather strange indirect relationship with the case of serial killer Dennis Nilsen. Back in the 1980s, my father’s cousin was either married or engaged (I cannot remember which) to a man, an officer in the Met, who worked on the Nilsen case and entered the murderer’s flat of horrors. We only saw this chap once or twice a year – mostly over the Christmas period, when my gran would orchestrate family gatherings by inviting various members of the family to stay with her over between Christmas and New Year. Even though I was a young child, I was allowed to stay up late during these Christmas gatherings, and I would watch, munching on chocolates and other goodies, as my father’s family drank and chatted, having not seen each other for months or perhaps an entire year. Staying up late was a delight, as I was exposed to all sorts of forbidden things – including, memorably, screenings of the early wave of Friday the 13th films – and, most impactfully on my young imagination, my dad’s cousin’s partner’s story of how Nilsen was caught (the infamous story involving a blocked drain, a Dyno-Rod employee, and a severed human hand) and what horrors awaited the officers who entered his flat.

Not that this story was treated lightly or was blurted out as if it were a tall story. That was not the case at all. Instead, this man – who would arrive as a very confident, striking sort of chap – would, as the evening progressed, become more hollow and morose. As the night would be topped off with a glass of whisky or two, someone would say something that would lead to the story being teased out of him – like a dark confession. Even in my naïve childhood, I knew that this was an unburdening of the soul: a story that, in its telling, the teller hoped would exorcise him of the memory. In this, I saw from a young age how someone could be haunted by their experience of such horrors, and there was an equivalence in how this dreadful story was approached, and how my own grandfather sometimes made oblique mention of the awful things he had seen at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

Shot on 16mm, Cold Light of Day invites comparisons with John McNaughton’s rough Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986, but only released in 1989 – the same year as Fhiona-Louise’s film) and the grimy Nekromantik (1987) by Jorg Buttgereit. Like those, it’s a grim, coarse film: its very coarseness, in fact, is used as a badge of authenticity.

Cold Light of Day tells the story of Dennis Nilsen – or rather, Jorden March: the story is a fictionalised account of Nilsen’s murders and arrest, though the veil of fiction is extremely thin here. March is played with quietly sleazy menace by Bob Flag, who had been the face of Big Brother in Michael Radford’s 1984 adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Here, he stalks greasy spoon cafes looking for rough trade amidst the grimy ketchup bottles and salt shakers. Cold Light of Day tells the story of Dennis Nilsen – or rather, Jorden March: the story is a fictionalised account of Nilsen’s murders and arrest, though the veil of fiction is extremely thin here. March is played with quietly sleazy menace by Bob Flag, who had been the face of Big Brother in Michael Radford’s 1984 adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Here, he stalks greasy spoon cafes looking for rough trade amidst the grimy ketchup bottles and salt shakers.

Cold Light of Day opens with ominous, discordant sounds on the audio track, accompanied by birdsong and a montage of mundane London locations. Two members of CID arrive at March’s flat. March is arrested, and we see him being interviewed. (He is offered a very civilised, very English cup of tea as a precursor to an attempt to get him to confess to murdering, mutilating, cannibalising and necro-fucking a number of young men.) March is a civil servant, a very unassuming man: the very definition of the banality of evil (‘I fill in lots of monotonous grey forms’, he says later in the film), to murder (pardon the pun) Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase.

The film crosscuts the interview room and March’s story. We see him in a pub, drinking white wine, as he strikes up a conversation with a young man, Joe (Martin Byrne-Quinn). An art student on his crust, Joe goes back to March’s flat. The two men sleep together but it’s unclear if they have sex. March spies on Joe bathing, and they go to a café together here March berates Joe for looking at another fella.

Meanwhile, we see March treating his neighbours with kindliness and respect – helping his elderly downstairs neighbour, Mr Green (Bill Merrow), when he soils himself. Here, March demonstrates incredible patience and altruism. When he offers Joe a place to stay, we might wonder whether this was intended – at least initially – as an equally altruistic act: or did March have other plans from the outset? When Joe mocks March’s landlady, Miss Stay (Jackie Cox), March puts him right: ‘You shouldn’t make fun of her’, March tells the younger man, ‘She’s probably lonely’.

March has told everyone that Joe is his nephew. However, he quickly becomes resentful of Joe’s freeloading and promiscuity. ‘You ungrateful bitch!’, March yells at Joe in one scene; to which Joe responds, ’God, you sound so camp, you do’. It isn’t long before March murders Joe, strangling him with a necktie before washing the body in the bathtub. March sleeps with the corpse next to him, hugging it. This incident is the catalyst in a series of murders – March cruising and picking up young men, taking them home and strangling them before washing their bodies, chopping up the corpses, boiling and cooking body parts, and wrapping the remains in binbags before stuffing them under his floorboards. March has told everyone that Joe is his nephew. However, he quickly becomes resentful of Joe’s freeloading and promiscuity. ‘You ungrateful bitch!’, March yells at Joe in one scene; to which Joe responds, ’God, you sound so camp, you do’. It isn’t long before March murders Joe, strangling him with a necktie before washing the body in the bathtub. March sleeps with the corpse next to him, hugging it. This incident is the catalyst in a series of murders – March cruising and picking up young men, taking them home and strangling them before washing their bodies, chopping up the corpses, boiling and cooking body parts, and wrapping the remains in binbags before stuffing them under his floorboards.

March is in many ways sympathetic – downtrodden and treated with disregard by Joe, who takes advantage of March’s kindness. A good, kind neighbour, in the scenes set in the diegetic present we see March being handled cruelly by the police. (When Inspector Simmons suggests March deliberately went out to find young men to kill, March is reduced to a snivelling wreck: ‘I didn’t go out to murder… It… just happened’, he protests.) It’s a fairly three-dimensional treatment of the story of a murderer.

More depth is added in flashbacks-within-the-flashback, which show March as a young boy – on a trip to the coast with his doting grandfather. The two lark about, throwing stones into the water and such, but March’s granddad dies suddenly, presumably from a heart attack. The devastated boy is then forced by his shrill, domineering mother to view his grandfather’s body in its coffin. Cold Light of Day suggests – somehow – that this event was significant in March’s life, determining his direction as an adult and his predilection for murder – but also his kindness to his elderly neighbour.

Certainly, March’s sexuality is curiously indeterminate. He takes voyeuristic pleasure in surreptitiously watching Joe bathe, and sleeps with the young men he takes home. However, when Inspector Simmons asks him ‘Did you screw them? Did you fuck their bodies?’, an indignant March responds: ‘No, they were too beautiful for mere, crude sex’. In one scene, after the murder of Joe, March is shown engaging a female prostitute. In particularly grim surroundings, she masturbates him – but there’s a mutual sense of repulsion and guilt from both participants.

There’s an easy naturalism to the proceedings – in the photography and dialogue (‘Can I use your bog? Ta!’, Joe asks March upon arrival at March’s flat) – and in all, it’s a profoundly gritty film, the rough and ready production and aesthetic complementing the material. Produced by Richard Driscoll, the Ed Wood of British filmmaking, in its impact Cold Light of Day easily eclipses anything in Driscoll’s career as a director. In fact, it’s a shame that its director, the enigmatic Fhiona-Louise, never went on to make any further pictures.

Video

Cold Light of Day is presented on Arrow’s Blu-ray in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film’s original aspect ratio, 1.37:1, is preserved. The film is also uncut, with a running time of 79:38 mins, and fills approximately 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Cold Light of Day is presented on Arrow’s Blu-ray in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film’s original aspect ratio, 1.37:1, is preserved. The film is also uncut, with a running time of 79:38 mins, and fills approximately 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.

Shot on 16mm, Cold Light of Day looks deliberately rough and grimy. Low-light scenes, shot on faster stock, have a particularly coarse grain structure – and this is thankfully retained by an excellent, filmlike presentation and an equally pleasing encode to disc. There’s a very strong level of detail throughout the presentation, and contrast levels are very good too – with defined midtones and deep blacks. There are quiet fluctuations in colour which are presumably owing to photochemical degradation of the source materials.

The presentation is based on a new 2k restoration from the original negative, and has been approved by Fhiona-Louise. In sum, it’s an excellent, very filmlike presentation of a picture whose photography was intentionally rough-and-ready.

NB. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. The original sound recording is equally rough – but the audio track on this release has a pleasing sense of fidelity. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- Audio commentary with Dean Brandum and Andrew Nette. Australian critics Dean Brandum and Andrew Nette offer a commentary on the film. They talk about Fhiona-Louise’s handling of the Nilsen murders, and discuss at length the circumstances of the Nilsen case – reflecting on the relationship between this particular film and Nilsen’s crimes.

- Audio commentary with writer and director Fhiona-Louise. Fhiona-Louise provides a commentary for the film. Interviewed by Ewan Cant, she talks about the genesis of the project. She discusses her background in fine art and how she came to become involved with Richard Driscoll, and her experiences visiting the set of Driscoll’s The Comic and watching the completed film a few years later. She talks about the short films in which she acted for Jon Jacobs, which were made in order to raise money for an intended feature film. Fhiona-Louise was intended to have acted in a Driscoll film called Body Electric, and she was sent to study acting with Mariana Hill. She came to make Cold Light of Day after ‘hit[ting] a wall in terms of painting’ – which was her primary artistic outlet. She came to the Nilsen story through a friend who had been involved with one of the men killed by Nilsen. She and Cant discuss the media coverage of the Nilsen murders, and compare this with the coverage of the Jeffrey Dahmer killings in the US – and suggest that Nilsen’s crimes were facilitated to some extent by the invisibility of gay men – who would disappear without investigation or recrimination. There’s a wonderful moment in which Fhiona-Louise and Cant discuss how filmmaking has changed, Fhiona-Louise praising the digital restoration of this film, and Cant refers to ‘grain reduction’ as ‘the work of the devil’ – with Fhiona-Louise adding that ‘It’s horrid’. This is an excellent commentary track, and Fhiona-Louise is a warm, thoughtful commentator.

- ‘Playing the Victim’ (15:49). Martin Byrne-Quinn, who plays Joe in the film, speaks about is work on the picture. Byrne-Quinn had previously worked in theatre, and this was his first feature film role. He reveals that he and Fhiona-Louise, both Method actors, had shared the same acting teacher, Mariana Hill (who had of course played Marisol in Sergio Leone’s Fistful of Dollars). Fhiona-Louise approached Byrne-Quinn about the idea of making a film focusing on the Nilsen murders, and they shot the short promotional film that is also included as an ‘extra’ on this disc. Byrne-Quinn talks about the production and the empathy he felt with Fhiona-Louise, as they both came from similar acting backgrounds – and he praises the clarity of her direction.

- ‘Risky Business’ (5:25). Steve Munroe, who appears in a fairly small part in the picture, discusses his part in the production. Munroe had of course already starred in producer Richard Driscoll’s 1985 film The Comic, also recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here. He discusses the guerrilla-style approach with which his scenes were filmed. The scene was shot with some carefully improvised dialogue, but Munroe suggests that the mics weren’t used effectively – so very little of this dialogue can be heard in the finished film.

- ‘Scenes of the Crime’ (13:38). Fhiona-Louise and Arrow Video producer Ewan Cant look at some of the locations used in the film – beginning in Soho, with some of the scenes shot around the Golden Lion pub where the real Dennis Nilsen cruised for victims. Fhiona-Louise asked for permission to shoot in some of the pubs but they turned her down, not wanting their businesses to be associated with the Nilsen story. They move on to Covent Garden Market, and some of the locations on the Embankment. Fhiona-Louise reveals that over the years, she has been contacted by a number of young men who are fans of the film because of their fascination with erotic asphyxiation. She also reveals that she was particularly influenced by Hitchcock’s Rope.

- Original Promotional Film (4:39). This is the original short that Fhiona-Louise made in order to raise funds for the feature film. It’s videotape-sourced and essentially a montage of key scenes anchored by a voiceover narration – but quite effective.

- Re-release Trailer (1:04).

- Short Films: ‘Metropolis Apocalypse’ (1988) (9:16); ‘Sleepwalker’ (1993) (3:29). These two short films both feature Fhiona-Louise in an acting role and were directed by Jon Jacobs. Shot in black and white, and in a non-anamorphic 2.35:1 screen ratio, ‘Metropolis Apocalypse’ is a quite poetic film – a series of images of crowds, candid-style street footage and time-lapse that is reminiscent of Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982) – and is anchored by a whispered voiceover reading of a poem. ‘Metropolis Apocalypse’ is sourced from video (though seems to have been shot on film?). ‘Sleepwalker’ seems to be film-sourced and is also in 2.35:1. Photographed in colour, it’s an enigmatic short film which cross-cuts several layers of ‘reality’.

Overall

The film would perhaps work better without its flashback structure – or with a more minimal use of the crosscutting between the police interview (in the diegetic present) and March’s crimes. Flag is superb as the Nilsen stand-in: bland, middle-aged, unassuming. Fhiona-Louise’s deadpan direction of the film is assured and fits the material like a glove, resulting in a picture that is worthy of comparison with McNaughton’s contemporaneous Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. It’s an incredible shame that Fhiona-Louise didn’t make any further films. The film would perhaps work better without its flashback structure – or with a more minimal use of the crosscutting between the police interview (in the diegetic present) and March’s crimes. Flag is superb as the Nilsen stand-in: bland, middle-aged, unassuming. Fhiona-Louise’s deadpan direction of the film is assured and fits the material like a glove, resulting in a picture that is worthy of comparison with McNaughton’s contemporaneous Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. It’s an incredible shame that Fhiona-Louise didn’t make any further films.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Cold Light of Day contains a very impressive, deeply filmlike presentation of this roughly-shot 16mm production. It is a deeply pleasing presentation. The film is supported by some truly superb contextual material. In particular, the locations featurette with Fhiona-Louise, and the director’s commentary are superb – with Fhiona-Louise being an affable and engaging commentator, offering some candid thoughts about the film and its themes – not to mention some of the more outre fans of the picture.

Please click to enlarge.

|