|

|

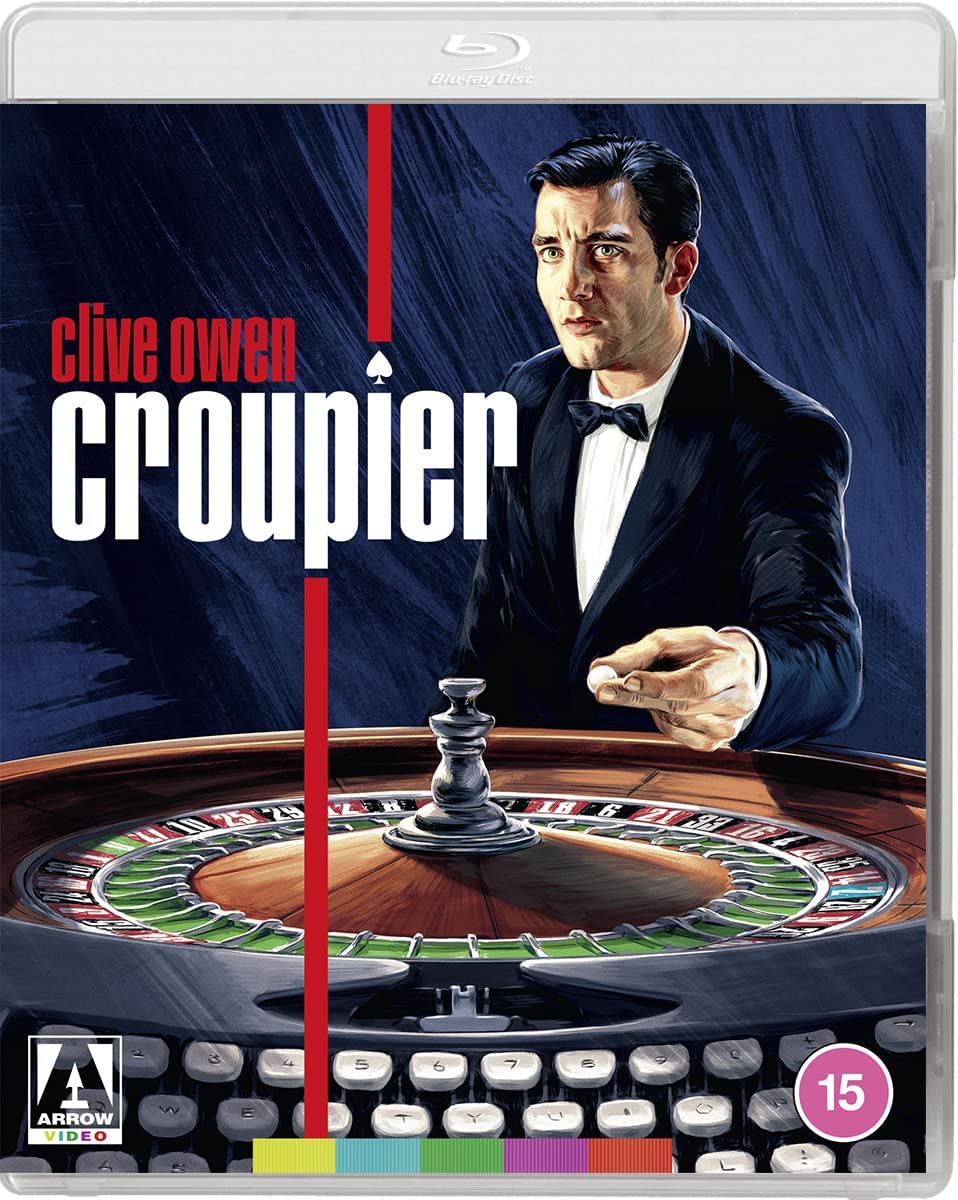

Croupier (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th December 2022). |

|

The Film

Croupier (Mike Hodges, 1998)  The career of director Mike Hodges is nothing if not diverse. Hodges began his career as a director of television documentaries for programmes such as World in Action, before directing two groundbreaking teleplays (“Suspect” and “Rumour”) for ITV’s Playhouse strand in 1969/1970. (I’ve written about “Suspect” and “Rumour,” released on DVD by Network Releasing, for this site here.) In “Suspect” and “Rumour,” Hodges adapted his experience making documentaries to fiction, resulting in a deeply naturalistic approach that influenced Euston Films’ later television productions, and their location-based and shot-on-film aesthetic, during the 1970s. The career of director Mike Hodges is nothing if not diverse. Hodges began his career as a director of television documentaries for programmes such as World in Action, before directing two groundbreaking teleplays (“Suspect” and “Rumour”) for ITV’s Playhouse strand in 1969/1970. (I’ve written about “Suspect” and “Rumour,” released on DVD by Network Releasing, for this site here.) In “Suspect” and “Rumour,” Hodges adapted his experience making documentaries to fiction, resulting in a deeply naturalistic approach that influenced Euston Films’ later television productions, and their location-based and shot-on-film aesthetic, during the 1970s.

Hodges then worked on his first theatrical feature, Get Carter: an adaptation of Barton-Upon-Humber author Ted Lewis’ novel Jack’s Return Home, Get Carter extended the gritty naturalism of Hodges’ teleplays and documentaries. Almost as if he had stared into an abyss for too long, Hodges subsequently retreated into more playful territory, with the B-movie homage Pulp (1972, the Arrow Video Blu-ray release of which has been reviewed by this writer here) and work within the SF and fantasy genres (The Terminal Man in 1974; Flash Gordon in 1980). These films were no less thought provoking than Hodges’ early work and maintained a dry focus on social issues, but eschewed a sense of gritty realism for a tone that often oscillated between black comedy, satire, and broad humour. In the mid-1980s, however, Hodges’ work gradually returned to territory that was more grounded and realistic, with A Prayer for the Dying (1987) and Black Rainbow (1989). Neither film was particularly well-received on its initial release, though both have gained strong cult followings in the years since. Hodges’ final two theatrical features, at least to this date, are two black-as-black neo-noir outings, both anchored by the presence of Clive Owen (the Actor Who Should Have Been Bond): Croupier (1998) and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (2003). The first of these, Croupier, has finally been released on Blu-ray and 4k UHD by Arrow Video. I say finally, because Croupier has long been difficult to find on home video formats – other than its initial UK DVD release from 2001 or thereabouts.  Written by Paul Mayersberg – a former film critic best known for his screenplays for Nic Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth and Eureka, and Oshima Nagisa’s Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence – the premise of Croupier originated in a spec script that Mayersberg wrote about a casino heist. This script was drafted in the 1970s, and over the next two decades the concept evolved into a story about a croupier who inadvertently becomes involved in a heist: the shift in focus from the criminals to the croupier came about when Mayersberg stayed in a hotel adjoined to a casino during the production in South Africa of his 1990 film The Last Samurai. Written by Paul Mayersberg – a former film critic best known for his screenplays for Nic Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth and Eureka, and Oshima Nagisa’s Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence – the premise of Croupier originated in a spec script that Mayersberg wrote about a casino heist. This script was drafted in the 1970s, and over the next two decades the concept evolved into a story about a croupier who inadvertently becomes involved in a heist: the shift in focus from the criminals to the croupier came about when Mayersberg stayed in a hotel adjoined to a casino during the production in South Africa of his 1990 film The Last Samurai.

Croupier focuses on Jack Manfred (Clive Owen), a struggling writer who at the urging of his distant father (Nicholas Ball) takes a job as a croupier at a casino managed by Reynolds (Alexander Morton). Working nights at the casino takes a toll on Jack’s relationship with his store detective girlfriend Marion (Gina McKee). Jack strikes up a friendship with Matt (Paul Reynolds), who seems all too willing to bend the casino’s strict rules against fraternising with clients outside work, and catches the eye of Bella (Kate Hardie). One night at the casino, Jack serves a South African woman, Jani (Alex Kingston). By coincidence, during the day Jack and Jani bump into one another, and Jani invites Jack for a drink – which is strictly verboten according to the rules of the casino. However, Jack accepts Jani’s invitation; the two chat, Jack revealing that he formerly worked as a croupier in South Africa and recognised Jani’s Capetown accent immediately. After a shift at the casino, Jack is assaulted by a patron who blames Jack for having him expelled from the establishment. Bella gives Jack a lift; the pair end up at Bella’s flat. Driven by adrenaline (and Jack’s sexual frustrations in his relationship with Marion), Jack and Bella fuck and, afterwards, smoke a joint. Marion becomes frustrated with Jack’s focus on his work as a croupier: she fell in love with Jack-the-writer (complete with bleached blonde hairdo) not Jack-the-croupier. Jack and Marion’s already strained relationship reaches breaking point when Bella arrives on the doorstep of their flat: having been fired by Reynolds because someone grassed to the casino management about Bella’s marijuana habit, Bella assumes Jack is the snitch and confronts him. Angrily, she tells Marion about Bella and Jack’s one-night stand.  Marion leaves Jack. Jack is invited to a soiree that has been organised by his literary agent, Giles (Nick Reding). Jack calls up Jani and invites her to attend with him: however, he warns Jani, they will probably need to share a bed. At Giles country house, Jani clumsily tries to seduce Jack by getting into their shared bed naked. However, Jack shows no interest in sex and falls asleep. During the night, Jani awakens Jack. She is in a state of panic. She says that she has in debt to a group of criminals who have told her to enlist Jack in a heist they are planning at the casino: all Jack will need to do is confront a cheating patron, thus creating a distraction for the gang. In exchange, Jack will be paid a substantial amount of money. Marion leaves Jack. Jack is invited to a soiree that has been organised by his literary agent, Giles (Nick Reding). Jack calls up Jani and invites her to attend with him: however, he warns Jani, they will probably need to share a bed. At Giles country house, Jani clumsily tries to seduce Jack by getting into their shared bed naked. However, Jack shows no interest in sex and falls asleep. During the night, Jani awakens Jack. She is in a state of panic. She says that she has in debt to a group of criminals who have told her to enlist Jack in a heist they are planning at the casino: all Jack will need to do is confront a cheating patron, thus creating a distraction for the gang. In exchange, Jack will be paid a substantial amount of money.

At the centre of Croupier is the enigmatic Jack, who narrates the story, sometimes slipping into the third person as if narrating a novel. (In fact, the film ends with Jack having written a published book about his work as a croupier, which is credited to “Anonymous.” Retrospectively, one wonders whether Jack’s narration may be taken from this novel.) Jack is a curiously affectless protagonist, an observer rather than an actor: within the film’s narrative, Jack is relatively passive, events happening to him rather than being directed by his narrative agency. “Jack was up above the world,” he narrates early in the film, “a writer looking down on his subject, a detached voyeur.” Jack is introduced as a struggling writer, his hair bleached blonde – trying to be someone else, running away from his past. As the film opens, he approaches Giles, his agent, who asks Jack to churn out a potboiler focusing on football. Jack is displeased and wants to work on his own ideas; he welcomes the distraction offered by the phone call from his estranged father – who tells Jack he has arranged for Jack to be interviewed for the job at Reynolds’ casino.  Jack was “born in a casino,” he says: this statement seems to be intended to be taken on both a literal and symbolic level. When interviewed for the position of croupier by Reynolds, Jack shows a preternatural talent for collecting chips, card dealing, and counting. (He quickly susses that Reynolds himself is unable to count.) Jack’s backstory is mixed into the dialogue by dribs and drabs: Jack, who holds the gamblers and their addiction to risk in contempt, almost pathologically insists to Reynolds that he doesn’t gamble. We infer that Jack’s father, who Reynolds says has “a bit of a reputation,” may have had a gambling problem that affected Jack deeply during his formative years. “Jack imagined people reading his book,” he narrates at one point, “He would tell them you have to make a choice in life: be a gambler or a croupier, and then live with your decision come what may.” The decision between being a dealer or a gambler seems to be an existential one: Jack has chosen to be a croupier, to deal the cards and take pleasure in watching the players lose. Jack was “born in a casino,” he says: this statement seems to be intended to be taken on both a literal and symbolic level. When interviewed for the position of croupier by Reynolds, Jack shows a preternatural talent for collecting chips, card dealing, and counting. (He quickly susses that Reynolds himself is unable to count.) Jack’s backstory is mixed into the dialogue by dribs and drabs: Jack, who holds the gamblers and their addiction to risk in contempt, almost pathologically insists to Reynolds that he doesn’t gamble. We infer that Jack’s father, who Reynolds says has “a bit of a reputation,” may have had a gambling problem that affected Jack deeply during his formative years. “Jack imagined people reading his book,” he narrates at one point, “He would tell them you have to make a choice in life: be a gambler or a croupier, and then live with your decision come what may.” The decision between being a dealer or a gambler seems to be an existential one: Jack has chosen to be a croupier, to deal the cards and take pleasure in watching the players lose.

Jack has other addictions, however: he participates in some bountiful daytime drinking, pouring tumblers full of vodka from a bottle stored in the icebox of his fridge. Jack’s drinking bubbles away in the background, contributing to a stereotype that the film builds (and which Jack aspires to) of the craft of writing; it goes unchallenged by Marion, who provides Jack with liquor. For all intents and purposes, Jack is a functioning alcoholic: the only time he seems to be impaired by his alcohol consumption is during a sequence in which Matt offers him a lift home, and Jack accepts. Matt takes a detour to a Greek restaurant, populated by various patrons of the casino – thus breaking one of the casino’s golden rules, which stipulates that croupiers must not mix with patrons outside work. There, Jack drinks heavily and is propositioned by a woman (played by glamour model/porn star Vida Garman) but turns her down, later finding her fucking another man in the restaurant toilets. Resisting temptation, he calls Marion at the flat, before returning to her. The casino takes its toll on Jack’s regular life, to the point that as the narrative progresses, Jack seems to lose sight of his writerly ambitions – though returns to these as the film builds to its climax. “Casino work doesn’t mix with house and garden,” Reynolds tells Jack during Jack’s interview at the casino. Soon, Jack finds his nocturnal work at the casino having a detrimental impact on his relationship with Marion. The film never states it directly, but the biggest impact seems to be on the couple’s sex life: Jack comes to bed whilst Marion is still in deep sleep, and Marion leaves for work whilst Jack is slumbering. His libido frustrated, Jack nevertheless sidelines Bella when she enters the staff locker room at the casino and strips topless in front of Jack, changing into her uniform. (“Tits in a uniform,” Bella tells Jack shortly afterwards, “Punters love it.”) Jack’s sexless nature is extended in the sequence in which he and Jani spend the evening at Giles’ country house. Jani enters the bedroom completely naked, clearly intending to seduce Jack and thus use her sexuality to lure him into being complicit in the casino robbery; but Jack shows no interest in her. Instead, a weeping Jani wakes Jack during the night, persuading him into co-operating during the robbery by presenting herself as a damsel in distress. (She tells Jack that she owes money to the men who are planning to rob the casino, and needs Jack to co-operate so she can clear her debts with them.)  Later, after being physically attacked outside the casino by an irate punter who Jack had expelled for cheating, Jack returns with Bella to her flat. They fuck angrily on the floor, Jack’s sex drive seemingly having been boosted back into action by the violence outside his and Bella’s workplace. Elsewhere in the film, Jack resists the sexual temptations of both the woman in the Greek restaurant and Jani: here, it isn’t that Jack has seduced Bella, or that Bella has seduced Jack, but instead the act of coitus seems to be motivated purely by adrenaline and convenience (in the form of one body’s proximity to another). Afterwards, they smoke a joint together and Jack departs; after having been fired from the casino for dope, Bella assumes Jack has shopped her to Reynolds and angrily confronts Jack on the doorstep of his and Marion’s flat. Bella reveals to Marion that she and Jack have slept together. Later, Jack will surmise that the slimy Matt, whose advances Bella has rebuked previously, was the true culprit behind the firing of Bella; it is implied that in retaliation – or perhaps because Matt reminds Jack of his father, another “escape artist” – Jack shops Matt to the casino management for various indiscretions. Later, after being physically attacked outside the casino by an irate punter who Jack had expelled for cheating, Jack returns with Bella to her flat. They fuck angrily on the floor, Jack’s sex drive seemingly having been boosted back into action by the violence outside his and Bella’s workplace. Elsewhere in the film, Jack resists the sexual temptations of both the woman in the Greek restaurant and Jani: here, it isn’t that Jack has seduced Bella, or that Bella has seduced Jack, but instead the act of coitus seems to be motivated purely by adrenaline and convenience (in the form of one body’s proximity to another). Afterwards, they smoke a joint together and Jack departs; after having been fired from the casino for dope, Bella assumes Jack has shopped her to Reynolds and angrily confronts Jack on the doorstep of his and Marion’s flat. Bella reveals to Marion that she and Jack have slept together. Later, Jack will surmise that the slimy Matt, whose advances Bella has rebuked previously, was the true culprit behind the firing of Bella; it is implied that in retaliation – or perhaps because Matt reminds Jack of his father, another “escape artist” – Jack shops Matt to the casino management for various indiscretions.

Jack’s double life (as writer and as croupier, by day and by night, in bed with Marion and in the bed of Bella) makes him difficult to read. “You’re an enigma, you are,” Marion tells him. “I’m not an enigma,” Jack replies, “just a contradiction.” Jack soon realises that Marion has a double life too. After they separate, he sees her kissing a man – a former detective colleague from her days in the Met – who later reveals to Jack that he was in love with Marion. This revelation reminds us that Marion has a depth to her, and a background, that neither Jack nor the film’s audience (who experience the film through Jack’s eyes) have previously been privy to. Jack and Marion’s relationship is also undercut by the noticeable difference in terms of social class/background between the pair. When Jack confronts Marion over her use of bad language, she spits back angrily: “Well, that’s my poor upbringing. I didn’t go to private school; I haven’t got any class.” Nevertheless, Jack is anchored by his relationship with Marion: “You’re my conscience,” he tells her. It is only when the couple drift apart that Jack becomes susceptible to the machinations of femme fatale Jani – but, as outlined above, not because of the sexual opportunities she presents, but rather in terms of her perceived vulnerability.

Video

Croupier is presented on Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. (Arrow have released simultaneously a 4K UHD release of the film, with a 2160p presentation that uses the HEVC codec.) Croupier is presented on Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. (Arrow have released simultaneously a 4K UHD release of the film, with a 2160p presentation that uses the HEVC codec.)

Croupier is uncut and runs for 94:52 mins. The 35mm colour photography is captured superbly on the Blu-ray provided for review. (This writer has also purchased and seen the 4K UHD release, which improves on the 1080p presentation in contrast, detail, and clarity.) The presentation is based on a new 4K restoration of the film, which has been approved by Mike Hodges. The level of detail is very impressive, with fine detail being evident in close-ups and the natural grain structure of the film being captured within this: the encode to disc is solid throughout, ensuring the grain structure is consistent and filmlike. Contrast levels are very satisfying, with deep blacks; midtones are richly defined, and there is a smooth tapering into both the toe and shoulder. Highlights are balanced and even. Damage is negligible or non-existent. Colours are naturalistic and, again, consistent: revisiting this film on this Blu-ray release, it’s far easier to notice how muted the palette is within the scenes set within the casino, which seem to strip life out of the image and reduce everything to sharp, cold tones. In all, the Blu-ray release offers a superb upgrade from the previously-available DVD release of this film, and offers an excellent, deeply filmlike presentation of Croupier.

NB. Some full-sized screengrabs from the 1080p Blu-ray are provided at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented on the Blu-ray via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is deep and rich, displaying excellent range – though the film’s audio mix is by no means a “showy” one. (That said, the “clack” of the roulette ball hitting the wheel is captured in a satisfying manner.) Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the dialogue.

Extras

DISC ONE includes the following contextual material: DISC ONE includes the following contextual material:

- Audio commentary with Mike Hodges. This is the same audio commentary that appeared on the old UK DVD release. Hodges talks about his work on Croupier, discussing how he came to be attached to the project. He reflects on Paul Mayersberg’s script: though Hodges and Mayersberg had been friends for many years, this was the first time they worked together. Hodges was impressed with Mayersberg’s script; the film was made with significant funding from German sources, which meant that the picture had to be shot partly in Germany, with the studio which was used for the casino set (and Jack Manfred’s apartment) being near to Dusseldorf. Hodges also talks about working with Clive Owen, whom Hodges describes as “superb” owing to “the combination of his voice and his looks.” Hodges reflects at length on the logistics of shooting in the casino set, and he discusses the film’s approach to its enigmatic central character and his dual life as a writer and croupier. - Audio commentary by critic Josh Nelson. This is a new commentary for Croupier, by critic Josh Nelson. Nelson begins by talking about the distribution history of Croupier, highlighting how the film “suffered terribly” – alongside a number of other films by Hodges – in terms of its distribution. FilmFour seemed intent on selling Croupier straight to video, with the head of FilmFour openly criticising the picture. Croupier was effectively shelved by FilmFour for around two years, but was eventually released on the back of the BFI’s cinema rerelease of Hodges’ Get Carter. Released in the US, Croupier ended up being successful – both critically and commercially. Nelson describes Croupier’s release history as an “underdog tale.” Nelson dissects the film’s themes, exploring Jack’s role as observer and participant. Nelson talks about the use of a voiceover by Jack, which “raises the possibility that what we’re looking at is the story that Jack is writing rather than an objective flashback at the events as they happened.” - Interviews: ‘A Streak of Fortune’ (39:34). In this new interview, Croupier’s writer, Paul Mayersberg, talks about the origins of the script. Mayersberg says the film originated in the late 1970s, in a script he wrote about a casino raid that was loosely based on Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur. This script was handed to Clint Eastwood and James Coburn before the project stalled. Whilst working on The Last Samurai (Mayersberg, 1990) in South Africa, Mayersberg stayed in a hotel that was in the same building as a casino; this provoked him into revising his script about the casino raid, focusing on a croupier – who was a minor background character in the original script. Mayersberg began researching the work of croupiers, and established the film’s focus on a small casino. This is an excellent interview, with Mayersberg exploring the process of developing the concept behind his script. ‘Film, Scones and Fury’ (24:21). In another newly recorded interview, actress Kate Hardie, who plays Bella in the film, reflects on her relationship with acting. She never intended to be an actor, but became involved in screen acting through a role she secured in Runners (Charles Sturridge, 1983). This led to more film and television work. She talks about her role in Croupier, and talks about Mike Hodges’ approach to filmmaking. She also reflects on some of the other films in which she has acted. ‘Mike Hodges at the BFI’ (56:34). This is an audio recording of a talk Mike Hodges gave at the BFI in 1999. In it, Hodges explores his career, from his work on documentaries and his early television films Suspect (1968) and Rumour (1969) to the likes of Get Carter (1971). Hodges discusses his approach to cinema, and the impact of 1960s New Wave cinemas on his work. - Trailer (1:57). - Image Gallery.

DISC TWO contains the documentary Mike Hodges: A Filmmaker’s Life (121:17). This is an excellent feature-length documentary, made for Arrow, that hinges on a career-spanning interview with Hodges, conducted by critic David Cairns. Hodges talks about his approach to the filmmaking process, and reflects on his career in a film-by-film manner. In his comments, Hodges hints at a philosophy of life that is existential, perhaps even absurdist – and this is a worldview that has always seemed prevalent within his films. He reflects on death and corporeality quite extensively. Hodges talks about his youth and his early television features, “Suspect” and “Rumour,” before going on to talk about his theatrical features beginning with Get Carter. There are some excellent comments on Hodges’ relatively neglected episode of the 1972 ITV series The Frighteners (titled “The Manipulators”). Hodges refers to Flash Gordon as “such a weird film to make,” and discusses how he took over the project from Nicolas Roeg. He also talks at length about the problems he faced on A Prayer for the Dying; and he discusses how the critics “kick[ed] shit out of his final two films,” Croupier and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead. I’m a huge fan of Hodges’ work, and have been since my youth; and this documentary is just the kind of indepth examination of his work that I have hoped for many years to see. The documentary is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and with a LPCM 2.0 stereo audio track.

Overall

Croupier is a superb film. A thread of surveillance runs throughout the picture – from Jack’s unblinking gaze during conversations with other characters, Marion’s work as a store detective, the surveillance (including mirrored walls) that enables the casino to function and prevent theft, and the casino staff’s surveillance over (and informing on) one another’s transgressions. Owen brings a smouldering intensity to his performance as Jack Manfred, and he is surrounded by some superb performances from actors in secondary roles – particularly Gina McKee as the highly-strung Marion, and Alex Kingston as Jani. It’s a tightly-written script, too, and perfectly handled by Hodges. Croupier is a superb film. A thread of surveillance runs throughout the picture – from Jack’s unblinking gaze during conversations with other characters, Marion’s work as a store detective, the surveillance (including mirrored walls) that enables the casino to function and prevent theft, and the casino staff’s surveillance over (and informing on) one another’s transgressions. Owen brings a smouldering intensity to his performance as Jack Manfred, and he is surrounded by some superb performances from actors in secondary roles – particularly Gina McKee as the highly-strung Marion, and Alex Kingston as Jani. It’s a tightly-written script, too, and perfectly handled by Hodges.

This writer was lucky enough to catch Croupier on its limited UK cinema release, which rode on the coattails of the BFI’s rerelease of Get Carter in 1999. The fact that beyond its now-20 year old DVD releases, the film had almost fallen into obscurity seemed frustrating; thankfully, Arrow Video’s new Blu-ray (and 4K UHD) release has resurrected Croupier, offering a presentation of the film that is utterly superb. The main feature is supported with some excellent contextual material – particularly the new interview with the film’s writer, Paul Mayersberg. This release comes with the strongest recommendation. Please click the screengrabs below to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|